The chief cause of problems is solutions.

—Eric Sevareid [158]

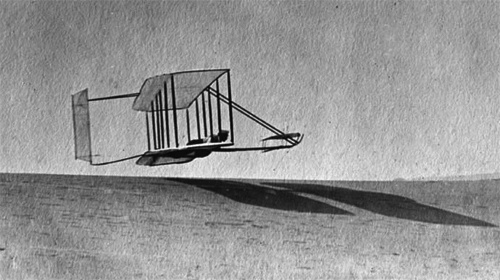

In 1903, two crazy young men, without any engineering training or college education, built a machine the world told them couldn't be made. In the frigid 30-mile per hour winds of Kill Devil Hills, a few miles from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the Wright brothers made the first sustained powered flight with a person at the controls (see Figure 10-1). Orville won the coin toss and flew first, but the brothers took turns, making four flights before calling it a day. As amazing as their accomplishment was, it went unnoticed: five boys from the nearby village made up most of the crowd. Only two small newspapers bothered to report on the event because it was seen as a stunt, not a technological breakthrough. It's hard to believe, but the Wright brothers landed their plane on a not very interested planet. The world would have to wait another 30 years for the commercial aviation industry to begin.

But the most curious thing about the development of powered flight wasn't the world's lack of interest in the Wright brothers' ideas: it was their pitch to potential investors. They didn't talk about multibillion dollar industries, revolutionizing travel across the planet, or connecting people around the world. Instead, their pitch centered on the most ambitious idea in the history of civilization: the end of war. [159] They imagined that their small aircraft, in the hands of democratic governments, could be used to observe enemy movements from afar, rendering surprise attacks and violent conflicts useless. [160] The Wrights spent six years pitching their idea to the governments of the U.S., France, Germany, and Great Britain, eventually selling an aircraft to the U.S in 1909.

Despite the wonders the airplane delivered to civilization, revolutionizing travel, commerce, and communication, it must have been tragic for Orville Wright to live through not one, but two World Wars with significant and strategic roles for aircraft. WWII saw the German Blitzkrieg, the U.S. fire bombings of Dresden (where hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed), and the only wartime uses of atomic bombs in history, all horrific events made possible by airplanes born of the Wrights' design. [161] Airplanes revolutionized warfare, changing forever the power balance of world politics in favor of those with superior air forces. And as the terrorist attacks on New York City on 9/11 revealed yet again, the uses of innovations like airplanes are impossible to predict.

In our religions, histories, and mythologies, we hold innovators to be great heroes, but we rarely speak their names when the downsides of their creations arise. In popular Greek mythology, the god Prometheus was loved for bringing fire to mankind, but shouldn't he also be partially accountable for the burning of Rome? Or, on a more personal level, if I gave you an apple pie that tasted good but later made you ill, wouldn't you complain? What if you bought a machine that saved you time but stained your clothes? Or a drink that doubled your efficiency but caused insomnia? It's overlooked by most, but some mythologies fear innovators. Prometheus, who brought fire to mankind, was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity (see Figure 10-2). The men who tried to build the Tower of Babel in the biblical book Genesis were cursed and divided across the world.

Figure 10-2. Rubens' famous painting of Prometheus Bound. In the myth, Prometheus is chained to a rock, and every day an eagle comes and eats his liver, which regenerates by the next day. In most mythologies, there is a price for innovation. Prometheus Bound was also the subtitle of Mary Shelly's Frankenstein.

The invention of the airplane certainly worked out well, especially if your last name is Boeing or you're a pilot. But what if, instead, you are the railroad mogul ruined by air travel's rise, or an honest family man who witnessed the destruction of your home by bombs dropped from airplanes? It's a different story. As we'll see, sorting out the meaning and impact of innovations is more complex than the task of making the innovations themselves.

We all think we know what good is, but like all definitions, its shine fades when applied to real life. What might be good for you, finding a thousand dollars in your underwear or waking up on a Maui beach, is probably bad for someone or something else (the person who lost the money, and the hapless sand crabs crushed beneath you). What we casually call good is never beneficial to everyone: it depends on who you are and where you stand. As Shakespeare wrote, "There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so," and our diverse thinking on goodness is reflected by the 50 or more definitions for the word good offered by most dictionaries.

The same goes for innovation. Is an innovation good if it solves your problems or makes you money? Definitely. But what if it also causes people to lose their jobs? Or, as is more often the case, what if after people spend days learning to use the innovation, there is little benefit? Or their lives are more complicated? And then consider plastics, typewriters, and televisions, innovations that have brought many good things to the world. But what of the 2-liter soda bottles resting forever in landfills, the typewriters that were used to schedule trains to Auschwitz, or the millions of children watching hours of adult television in lieu of day care? Can we call these, and others like them, innovations because they're good in the largest sense? And, despite all the positive revolutions they've brought to the world, personal computers leave a wake of toxins and chemicals behind every time they're replaced by newer machines. [162]

There's no easy answer to this examination of innovation goodness, leaving plenty of room, much like the previous chapter, for the mythology of "all innovation is good" to survive. We have so much history with innovation as the driving force for our culture, economy, and psychology—from the cotton gin and Industrial Revolution to the personal computer and the Internet Age—that our confidence in innovation approximates a faith; when in doubt, innovate, despite the growing wave of unanswered questions about innovations past.

But there is at least one truth: all innovations combine good and bad effects regardless of the intention of the innovator or how well designed they are. [163] If we accept this, and concede that perspective is everything when it comes to goodness, we can reframe our judgment of innovations.

An innovation can be:

Good for you. The innovation earns you money, is enjoyable to work on, or solves a problem that interests you.

Good for others. The innovation provides income to help family and friends; solves problems for the poor, sick, or needy; or through the innovation, or profits generated from it, improves the lives of people other than you.

Good for an industry or economy. The innovation has benefits for many businesses and creates new opportunities for at least a subset of an industry or economy. Disruptions caused by the innovation are outweighed by new opportunities created.

Good for a society. The innovation has a net positive effect on a community, city, state, or nation. While there might be some negative uses of the innovation, the net effect is overwhelmingly positive. The innovation is designed for sustained value, not just short term. The innovator identified who it might be bad for and tried to minimize those effects.

Good for the world. The innovation has a net positive on the future of the human race.

And we can also ask the twin questions:

What problems does this innovation solve? Whose problems are they?

What problems does this innovation create? Whose problems are they?

This list shows that many famous innovators can at best claim to have made things good for them, or good for corporations, with little value for others. (Having a large IPO or selling ideas for millions has debatable value on the goodness scale.) And many popular innovations—such as lightbulbs, automobiles, and computers—definitely benefit individuals and industries, but their contributions are tarnished by their negative environmental impacts. It gets complex quickly, but by framing the value of innovations on different perspectives, understanding innovation becomes possible. The biases or self-interests that limit definitions of goodness are forced to surface.

[160] This belief in technology, particularly weaponry, as ending war, was shared by the inventors of dynamite and the submarine. Tesla also built war machines with this ideal in mind. The telegraph, television, the Internet, and even neural implants have been heralded with the same war-ending powers. An observer of history might note the problems that lead to war seem to have nothing to do with technology and much to do with human nature.

[161] Einstein, whose E=mc2 played a pivotal role in the creation of nuclear weapons, agonized over the moral challenges involved with the use of his discoveries.http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/einstein/peace/manhattan.php.

[163] Certainly some creators can steer their creations one way or another. The inventor of a drug that cures stupidity or converts assholes into saints would be hard to criticize. Some inventors are agnostic about how their work is used, but in the cases of OXO good grips or prosthetic limb designers, there is definitely a goodness factor in how the thing itself is designed and the problems it intends to solve.