E-valuation (1) : not

business as usual?

7.1 Introduction

There are many, many companies on the Internet, but very few businesses.

Analyst Mary Meaker, Morgan Stanley (2000)

E can stand for electric or electronic, but at some point it will have to stand for earnings.

Chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, May 2000.

During the last few years we have witnessed rapid expansion in the use of the Internet and the World Wide Web. The e-business opportunity in the individual company is typically seen as dividing into internets, extranets and intranets, covering business-to-consumer (B2C), business-to-business (B2B) and internal use of web-based technology. On conservative figures, B2C will be worth US$184 billion by 2003, and B2B US$1,300 billion. We have also seen the rise of C2C and C2B uses, and E2E (everywhere-to-everywhere) connectivity is the next step to be contemplated. However, the rising expectations of payoff from these investments, fuelled by high stock valuations of Internet-based companies, dived from spring 2000. Subsequently, it has become obvious that the new technology's ability to break the old economic and business rules, and to operate on ‘new rules’ in a ‘new economy’, is constrained by the effectiveness of the business model it underpins and of business and technology management. Of course, this is a familiar story, which is also true of previous rounds of technology.

At the same time, the use of Internet-based technologies, in terms of speed, access, connectivity, and its ability to free up and extend business thinking and vision represents an enormous opportunity to create e-business, if it can only be grasped. This chapter, and Chapter 8, will focus on laying a framework for identifying e-business value, with the following observations as guidelines.

(1) As argued in Chapter 3, for any IT investment the contribution of Web-based technologies to business has to be defined before the allocation of resources.

(2) The changing economics of e-business breed discontinuities and uncertainties which need to be explored thoroughly in order to understand the implications of e-business investment decisions and related strategic decisions.

(3) Use of e-technologies does not contribute value in the same way to every business; thus, different types of e-business investment cannot be justified using the same approach. The various forms of e-business that evolve and the way they apply in different organizations and industries need to be explored.

In this chapter we establish the context of the evaluation challenges that businesses now face. We then look at the emerging possibilities for a new economics of information and technology as a result of the latest technologies. Finally, we illustrate some of these with an in-depth case study (see Chapter 8).

7.2 IT eras: a further complication to the evaluation problem

Reference has been made to the rapid evolution of information- based technologies, and the pervasiveness of their use in organizations. In his book Waves of Power, David Moschella1

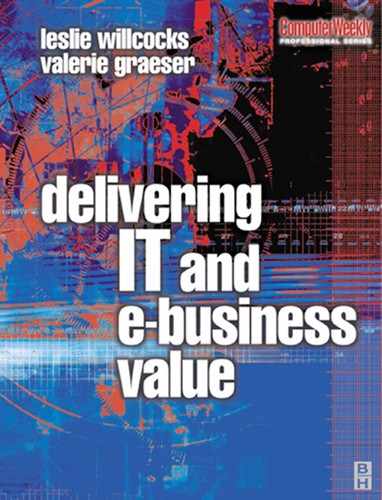

Figure 7.1 The resolution of the IT industry (adapted from Moschella, 1997)

frames this evolution as a series of technology eras and describes the dimensions of each era. The significance of this theory to IT evaluation is that most organizations do not transition cleanly and completely from one era to the next, but seek to apply a variety of technologies. However, invariably, they use a limited number of well-tried evaluation methods that, in fact, can rarely capture the full costs, benefits, risks and value of different technologies, embodying different economic laws.

Figure 7.1 charts various aspects across the eras. Up to 2001 and the present ‘network-centric era’, each has seen roughly six- to seven-year cycles of investment in specific technologies. Although technology innovation cycles have shortened, computer adoption times have stayed at about seven years because it takes at least that long to institutionalize related managerial, social and organizational changes. Let us look at each era in more detail.

The systems-centric era (1964–l1981)

It is generally accepted that this era began with the IBM S/360 series – the computer industry's first broad group of steadily upgradable compatible systems. The dominating principle throughout most of this period was that of Grosch's Law. Arrived at in the 1940s, this law stated that computer power increases as the square of the cost, in other words a computer that is twice as expensive delivers four times the computing power. This law favoured large systems. Investment decisions were fairly simple initially and involved centralized data centres. IBM dominated supply and protected its prices. In response to dissatisfaction with centralized control of computing by finance functions, there followed centralized timesharing arrangements with non-finance functions, some outsourcing by scientific, engineering and production departments to independent service suppliers, and subsequently moves towards small-scale computers to achieve local independence. This led to stealth growth in equipment costs outside official central IT budgets, but also a dawning understanding of the high lifecycle support costs of systems acquired and run locally in a de facto decentralized manner.

From about 1975 the shift from centralized to business unit spending accelerated, aided by the availability of minicomputers. Also, in a competitive market, prices of software and peripherals fell rapidly and continuously, enabling local afford- ability, often outside IT budgets and embedded in other expenditures. Without centralized control, it became difficult to monitor IT costs.

The PC-centric era 1981–1994

This era began with the arrival of the IBM PC in 1981. The sale of PCs went from US$2 billion in 1980 to US$160 billion in 1995. This period saw Grosch's Law inverted; by the mid- 1980s the best price/performance was coming from PCs and other microprocessor-based systems. The underlying economics are summarized in Moore's Law, named after one of the founders of Intel. This law stated that semiconductor price/ performance would double every two years for the foreseeable future. This law remained fairly accurate into the mid-1990s, aided by constantly improved designs and processing volumes of market-provided rather than in-house developed microprocessor-based systems. Additionally, the PC-centric era saw shifts from proprietary corporate to individual commodity computing. The costs of switching from one PC vendor to another were low, while many peripherals and PC software took on commodity-like characteristics. A further shift in the late 1980s seemed to be toward open systems, with the promise of common standards and high compatibility. However, it became apparent that the move was not really from proprietary to open, but from IBM to Microsoft, Intel and Novell.

These technical advances provided ready access to cheap processing for business unit users. IT demand and expenditure were now coming from multiple points in organizations. One frequent tendency was a loosening of financial justification on the cost side, together with difficulties in, or lack of concern for, verifying rigorously the claimed benefits from computer spending. From 1988 onwards, technical developments in distributed computing architecture, together with organizational reactions against local, costly, frequently inefficient microcomputer-based initiatives, led to a client-server investment cycle. The economics of client-server have been much debated. The claim was that increased consolidation and control of local networks through client-server architectures would lower the costs of computing significantly.

Although the PC-centric era is marked by inexpensive equipment and software relative to price/performance calculation, the era did not usher in a period of low-cost computing. Constant upgrades, rising user expectations, and the knock-on costs over systems’ lifecycles saw to that. By the mid-1990s the cost per PC seat was becoming a worrying issue in corporate computing, especially as no consistent cost benchmarks emerged. Published cost of ownership estimates range from US$3,000 to US$18,000 per seat per year, probably because of differences in technology, applications, users, workloads and network management practices. One response to these rising costs is outsourcing, examined in more detail in Chapter 6.

The network-centric era (1994–2005)

Although the Internet has existed for nearly 20 years, it was the arrival of the Mosaic graphical interface in 1993 that made possible mass markets based on the Internet and the Web. This era is being defined by the integration of worldwide communications infrastructure and general purpose computing. Communications bandwidth begins to replace microprocessing power as the key commodity. Attention shifts from local area networks to wide area networks, particularly intranets. There is already evidence of strong shifts of emphasis over time from graphical user interfaces to Internet browsers, indirect to on-line channels, client-server to electronic commerce, stand-alone PCs to bundled services, and from individual productivity to virtual communities.

Economically, the pre-eminence of Moore's Law is being replaced by Metcalfe's Law, named after Bob Metcalfe (inventor of the Ethernet). Metcalfe's Law states that the cost of a network rises linearly as additional nodes are added, but that the value can increase exponentially. Software economics have a similar pattern. Once software is designed, the marginal cost of producing additional copies is very low, potentially offering huge economies of scale for the supplier. Combining network and software economics produces vast opportunities for value creation. At the same time, the exponential growth of Internet user numbers since 1995 suggests that innovations which reduce usage costs whilst improving ease of use will shape future developments, rather than the initial cost of IT equipment – as was previously the case.

By 1999, fundamental network-centric applications included e-mail and the Web – the great majority of traffic on the latter being information access and retrieval. By 2001, transaction processing in the forms of, for example, e-commerce for businesses, shopping and banking for consumers, and voting and tax collection for governments was also emerging. The need to reduce transaction costs through technology may well result in a further wave of computer spending, as we have already seen with many B2B applications. Internet usage is challenged in terms of reliability, response times and data integrity when compared to traditional on-line transaction processing expectations. Dealing with these challenges has significant financial implications.

Many of these developments and challenges depend on the number of people connected to the Internet. Significant national differences exist. However, as more people join, the general incentive to use the Internet increases, technical limitations notwithstanding. One possibility is that IT investment will lead to productivity. In turn, this will drive growth and further IT investments. The breakthrough, if it comes, may well be with corporations learning to focus computing priorities externally (e.g. on reaching customers, investors and suppliers), rather than the historical inclination primarily towards internal automation, partly driven by inherited evaluation criteria and practices. Even so, as Moschella notes:

. . . much of the intranet emphasis so far has been placed upon internal efficiencies, productivity and cost savings . . . (and) . . . has sounded like a replay of the client-server promises of the early 1990s, or even the paperless office claims of the mid-1980s.

A content-centric era (2005–2015)

It is notoriously difficult to predict the future development and use of information technologies. One plausible view has been put forward by Moschella. The shifts would be from e-commerce to virtual businesses, from the wired consumer to individualized services, from communications bandwidth to software, information and services, from on-line channels to customer pull, and from a converged computer/communications/consumer electronics industry value chain to one of embedded systems. A content-centric era of virtual businesses and individualized services would depend on the previous era delivering an inexpensive, ubiquitous and easy-to-use high bandwidth infrastructure.

For the first time, demand for an application would define the range of technology usage rather than, as previously, also having to factor in what is technologically and economically possible. The IT industry focus would shift from specific technological capabilities to software, content and services. These are much less likely to be subject to diminishing investment returns. The industry driver would truly be ‘information economics’, combining the nearly infinite scale economies of software with the nearly infinite variety of content.

Metcalfe's Law would be superceded by the Law of Transformation. A fundamental consideration is the extent to which an industry/business is bit (information) based as opposed to atom (physical product) based. In the content-centric era, the extent of an industry's subsequent transformation would be equal to the square of the percentage of that industry's value-added accounted for by bit- as opposed to atom-processing activity. The effect of the squared relationship would be to widen industry differentials. In all industries, but especially in the more ‘bit-based’ ones, describing and quantifying the full IT value chain would become as difficult an exercise as assessing the full 1990s value chain for electricity.

Let us underline the implications of these developments, because they help to explain why IT/e-business evaluation presents such formidable challenges. As at 2001, organizations have investments in systems from the systems- and PC-centric eras, will be assessing their own potential and actual use of technologies of the network-centric era, while also contemplating how to become ‘content-centric’. We find that too many organizations tend to utilize across-the-board legacy evaluation methods, which in fact are more suitable for the economics and technologies of previous eras. What is needed is a much keener understanding of the economics of the network-centric era now upon us, so that better decisions can be made about choice of evaluation approaches.

7.3 The changing economics of e-business

Is a new economics developing? Consider some of the following emerging possibilities.

(1) Metcalfe's Law will become increasingly applicable from 2001 as information networks and e-commerce continues to expand globally, as a result of more users transacting via the Web.

(2) Digitalizing transactions can greatly reduce transaction costs both intra-organizationally and between businesses. Dell and Cisco Systems, for example, report massive savings from operating virtually. A senior manager at Dell explained that he saw inventory as the physical embodiment of the poor use of information. Lower transaction costs are a strong incentive to perform more business functions on the Internet. According to the established pricing schemes for the Internet, the price of some services is disproportional to their real value, that is the price consumers are prepared to pay. For commercial uses it is usually very low, thus giving more incentives to firms to migrate to Internet electronic transactions.

– In 1997, Morgan Stanley (the major investment bank based in New York) was reported to have achieved over US$1 million in annual savings after introducing a Web- based information server for firm-wide use. The 10,000 employees used the company's network on a daily basis to access information that used to be published and circulated internally on paper. By eliminating paper, the company reduced costs, whilst improving service and productivity. Information was up to date and it could be searched electronically. The user could find what he or she needed in much less time.

(3) On competitive advantage, it is true that wider availability of information can eliminate power asymmetry between corporations to a certain extent. However, new sources of information asymmetries are likely to appear. Furthermore, while low capital asset specificity of virtual business allows more firms to enter the market, talented, knowledgeable and innovative individuals will become an expensive and difficult-to-acquire asset of virtual corporations and a source of competitive advantage (see the case study of Virtual Vineyard in Chapter 8). Taking a resource- based view of how to compete would seem to be as important in the Internet era as in previous ones.

(4) Digital assets are often re-usable and can redefine economies of scope and scale. Production costs may be minimal. Digital goods comprise information that has been digitized and the medium on which the information resides, such as an application software disk.

Virtual goods, on the other hand, are the subset of goods that exist only in the virtual world. In the virtual value chain information as a by-product can become a marketable asset, cheap to create, store, customize and produce quickly on demand. Virtual goods are indestructible, in the sense that they do not tear off with use or consumption. However virtual goods may still be perishable or devalue over time; for example, people pay a premium to have early access to information about the stock market which is available for free just a few minutes later. As a result of the slippery nature of information value, business strategy must be defined very precisely and carefully through information value.

It is easy, fast and relatively cheap to reproduce digital goods, and it is even faster and cheaper to reproduce virtual goods. Production costs are almost zero, or are at least minimal. Therefore, it is the willingness of the consumer to pay rather than the marginal production cost that will determine the price of virtual goods. Inexpensive reproduction on demand also implies that there is no need for factories, production lines or warehouses. In the case of a virtual company selling a virtual good, there is not even need for physical presence. The logic is that low asset specificity will probably lead to new corporate and organizational forms. Size, hierarchy and assets management will be affected. Lower asset specificity also implies lower entry barriers to the market. This will result in a major shift of the balance of power in certain markets.

(5) In the traditional economics of information there is a tradeoff between richness and reach. According to Evans and Wurster2, this law is being challenged by the use of electronic communication networks. Richness refers to the quality of information, while reach refers to the number of people who have access to it. This pervasive trade-off has determined the way companies communicate, collaborate and contact transactions with customers, suppliers, distributors or internally. If this trade-off were eliminated or minimized, the established relations would be challenged and redefined.

(6) The significant disintermediation effects of applying Web- based technologies have been remarked upon for some time in a range of industries, including entertainment, travel, retail goods, computer sales and financial services. Even more interesting has been more recent developments in re- intermediation, as value-added services has sprung up to facilitate B2B and B2C in a variety of industries. As an example, there are now a range of meta-agents available to help view the best price and terms for buying books and CDs and many other items over the Web.

(7) As we shall see, the arrival of Web-based technologies creates an even wider range of possibilities than this, including:

– permitting a global presence in a virtual marketspace;

– the development of multimedia convergence enabling bundling of sounds, images and words in digital form, thus opening up new products and new market channels – which could be the prelude to a content-centric era;

– the development of virtual communities and their attendant economic value; and

– the further establishment of service- and informationbased differentiation on-line.

7.4 The e-business case: need for an evolutionary perspective

In light of these changing economics and the ever-developing power of Web-based and complementary technologies, the e-business case for investment is not always clear. Reporting in 2001, Willcocks and Plant3 found that many that had already gone forward with Web-enabled transactions perceived financial payback and time savings coming much later. One reason for caution would be the ability of Internet usage to magnify mistakes and make them intensely public. Thus, Machlis4 reports a major US credit-reporting agency sending 200 credit reports to the wrong customers, after 2,000 requests to the Web site over an 11-hour period triggered a software error, which misdirected the credit data. US firms have shown less caution with intranets, with 85% having installed them or planning to install them by mid-1997. By comparison, by 2001, the figure in the UK has been lower – the fear of being left behind often being counteracted by difficulties in identifying ‘killer applications’ for an intranet.

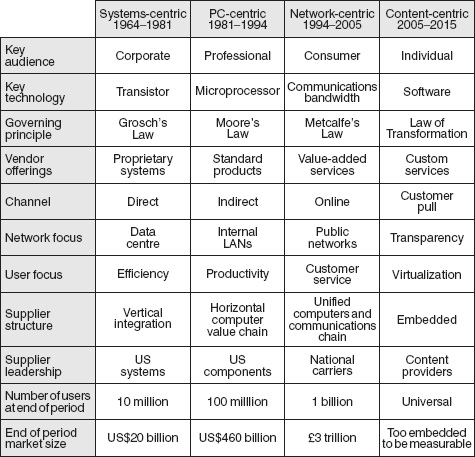

What then are the real benefit opportunities emerging? Considering the Web and the Internet, there can be several types of Web site. According to Quelch and Klein5, the primary drivers of the business model adopted are types of customer and preferred business impact (see Figure 7.2).

Existing companies, for example Motorola, UPS, Federal Express and 3M, have tended to evolve from using a site for image and product information purposes, to using it for information collection/market research, customer support/ service and internal support/service and then for transactions/ sales. On the other hand, simple economics require Internet start-ups, for example Amazon.com and Software.net, to begin with transactions, then build customer support/service, provide a brand image and product information, then carry out information collection and market research to win repeat purchases. These two different evolutionary models involve plotting different routes through the four quadrants shown in Figure 7.2. Whatever the positioning, it is clear that a Web site business case needs to show how revenue can be generated, costs reduced, customers satisfied and/or business strategies underpinned.

Figure 7.2 Drivers of the Internet business model (source: Quelch and Klein 1996)5

In fact, significant cost reductions are possible. In the first 18 months of Web usage Morgan Stanley, the US investment bank, documented nearly US$1 million in savings on internal access to routine information and electronic routing of key reports. By moving external customer support functions on to the Web, Cisco Connection Online saved US$250 million in one year. One immediate advantage and (following Metcalfe's Law) exponential add-on value of a Web site is that it can reach a global audience, although this may not be its initial focus. This global product reach can offer multiple business opportunities, including faster new product diffusion, easier local adaptation and customization, overcoming import restrictions, reducing the competitive advantage of scale economies in many industries, and the effective marketing and selling of niche/speciality products to a critical mass of customers available worldwide.

Clearly, the technology enables new business models, but these are a product of new business thinking and business cases that can recognize at least some of the longer-term benefits, although evidence suggests that many will also grow from use and learning. At the same time, on the cost side, Web sites, like other IT investments, are not one-off costs. Annual costs just for site maintenance (regardless of upgrades and content changes) may well be two to four times the initial launch cost.

Exploiting the virtual value chain

Benefits may also arise from exploiting the information generated in the virtual value chain of a business. Rayport and Sviokla6 have pointed out that if companies integrate the information they capture during stages of the physical value chain – from inbound logistics and production through sales and marketing – they can construct an information underlay for the business. One internal example is how Ford moved one key element of its physical value chain – product development of its ‘global car’ – to much faster virtual team working. Externally, companies can also extract value by establishing space-based relationships with customers. Essentially, each extract from the flow of information along the virtual value chain could also constitute a new product or service. By creating value with digital assets, outlays on information technologies such as intranets/internets can be reharvested in an infinite number of combinations and transactions.

Exploitation of digital assets can have immense economic significance in a network-centric era. However, organizations would need to rethink their previous ways of assessing benefits from IT investments. Rayport and Sviokla summarize the five economic implications. Digital assets are not used up in their consumption, but can be reharvested. Virtual value chains redefine economies of scale allowing small firms to achieve low unit costs in markets dominated by big players. Businesses can also redefine economies of scope by utilizing the same digital assets across different and disparate markets. Digital transaction costs are low and continue to decline sharply. Finally, in combination these factors, together with digital assets, allow a shift from supply side to demand side, more customer-focused thinking and strategies.

Further benefits and challenges

To add to this picture, Kambil7 shows how the Internet can be used in e-commerce to lower the costs and radically transform basic trade processes of search, valuation, logistics, payment and settlement, and authentication. Technical solutions to these basic trade processes have progressed rapidly. At the same time, the adoption of trade context processes to the new infostructure – processes that reduce the risks of trading (e.g. dispute resolution and legitimizing agreements in the ‘marketspace’) – has been substantially slower. This has also been one of the major barriers to wider adoption of electronic cash, along with the need for a critical mass of consumer acceptance, despite compelling arguments for e-cash's potential for improved service.

Some further insights into the new economics and the power to create value in on-line markets are provided by Hagel and Armstrong8. They too endorse the need for an understanding of the dynamics of increasing returns in e-commerce. E-business displays three forms of increasing returns. Firstly, an initial outlay to develop e-business is required, but thereafter the incremental cost of each additional unit of the product/service is minimal. Secondly, significant learning and cost-reduction effects are likely to be realized, with e-based businesses driving down the experience curve more quickly than mature businesses. Thirdly, as has been pointed out above, Metcalfe's Law applies – network effects accrue exponential returns as membership increases and more units of product/service are deployed. As Microsoft showed spectacularly in software, harnessing the power of increasing returns means ‘the more you sell, the more you sell’.

The new economics of electronic communities

Hagel and Armstrong focus particularly on the commercial possibilities inherent in building electronic communities. Here networks give customers/members the ability to interact with each other as well as with vendors. In exchange for organizing the electronic community and developing its potential for increasing value for participants, a network organizer (a prime example being that of Open Market Inc.) would extract revenues. These could be in the form of subscription, usage, content delivery or service fees charged to customers and advertising and transaction commission from vendors. Customers would be attracted by a distinctive focus, for example consumer travel, the capacity to integrate content such as advertising with communication (e.g. through bulletin boards) both of which aggregate over time, access to competing publishers and vendors, and opportunities for commercial transactions. Vendors gain reduced search cost, increased propensity for customers to buy, enhanced ability to target, greater ability to tailor and add value to existing products and services. They also benefit from elements more broadly applicable to networked environments: lower capital investment in buildings, broader geographic reach and opportunities to remove intermediaries.

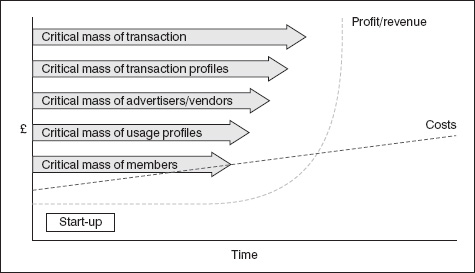

Hagel and Armstrong point out that the dynamics of increasing returns drive revenue growth in virtual communities, but these are easily missed by conventional techniques of financial analysis. Using static revenue models and assumptions of straight-line growth, these conventional techniques can underestimate greatly the potential of virtual community investment. As a result, organizations may forego investment altogether or under-invest, thereby increasing the risks of pre-emption by competitors and business failure.

Figure 7.3 Revenue, cost and milestones for virtual communities (modified from Hagel and Armstrong8)

Increasing returns depend on the achievement of four dynamic loops. The first is a content attractiveness loop, whereby member-based content attracts more members, who contribute more content. The second is a member loyalty loop. Thus, more member-to-member interaction will build more member loyalty and reduce membership ‘churn’. The third is a member profile loop, which sees information gathered about members assisting in targeting advertising and customizing products/services. The fourth is a transaction offerings loop, which sees more vendors drawn into the community, more products/services being offered, thus attracting more members and creating more commercial transactions. According to Hagel and Armstrong, it is the aggregate effect of these dynamic loops in combination that could create the exponential revenue growth pattern shown in Figure 7.3.

To achieve these four dynamic loops the first step is to develop a critical mass of members. The other four growth assets are shown in Figure 7.3. These may reach critical mass in a sequential manner, but community organizers may well seek to develop them much more in parallel as shown in Figure 7.3. The important point is that as each growth asset reaches critical mass and their effects combine, the revenue dynamic is exponentially influenced. However, despite Hagel and Armstrong's optimism, it should be emphasized that there is no inevitability about the scenario depicted in Figure 7.3. This has already been demonstrated throughout 2000 and early 2001 by the high-profile failures, such as Boo.com, Levi Strauss, ClickMango, Boxman and Value America, which have attempted this route. Business and competitive risks do not disappear, but are fundamental to the development and running of electronic communities.

In all this, as in more conventional businesses, the key economic asset is the member/customer, and critical activities revolve around his/her acquisition and retention. This can be costly on the Web, where ’surfing’ is much more typical than member loyalty. Up to 1999 even an experienced on-line service such as America Online was losing up to 40% of its members a year and spending up to US$90 to acquire each new member. Other cost aspects need to be borne in mind. Start-up costs for an Internet site are commonly cited as low – typically between US$1 million and US$3 million depending on size and ambition, although this is a figure regularly being re-estimated upwards. On one model, technology-related costs in an electronic community may start as a small (say 35%) and decline as a proportion of total costs over a five-year period, being overwhelmed by member and advertiser acquisition and content-related costs – as many Internet-based companies have found already.

However, those making investment decisions do face a number of challenges. A look at Figure 7.3 would suggest that fast returns on investment are unlikely, while short-term cost pressures are certain. Moreover, evidence from the Internet has been that early revenue sources such as membership subscription and usage fees, and advertising charges, act as dissuaders and can slow long-term growth substantially. Moreover, even by 2001, the Internet was still not a wholly commerce-friendly environment, with key robust technologies on payment, authentication, security and information usage capture still to be put in place, and with already a history of security breaks, virus attacks and organizations with inadequate e-business infrastructure.

7.5 Summary

With the network-based era now upon us, we usher in for ourselves many new technological and economic realities. These have to be understood if IT evaluation practices are to be properly informed and are to perform meaningful asessments of the IT investments made by organizations. This chapter, together with Chapter 2, has attempted to make clear that the difficulties experienced consistently with IT evaluation over the years are now being compounded by the many layers of types of technology and their often differing purposes found in most reasonably complex organizations in the developed economies. Moreover, there is always tomorrow's technology, the uncertainty about its necessity and the question of whether it will be the ‘killer application’ or just another expensive addition to the corporate budget. In increasingly competitive markets there are also rising concerns about being left behind, by-passed or locked out, for example when a start-up company or an existing competitor moves from the marketplace to the ‘marketspace’. In such circumstances, properly informed IT assessment practices are as vital as ever. The technology shifts and their underlying economics detailed in this chapter imply that for IT evaluation practices, in several important ways, it can no longer be business as usual.

7.6 Key learning points

– The rapid expansion and massive potential of the Internet sets significant challenges for businesses and their IT investment procedures.

– The contribution of e-business has to be defined before the allocation of resources. As with other IT-based applications, the business drivers behind the investment must be totally clear. Otherwise, the project must be treated as R–D and an investment in learning.

– Significant discontinuities stem from the fluid, underlying economics of e-business. It is necessary to explore these thoroughly in order to understand the context and economics underpinning stategic and investment options.

– Internet-based applications offer a multitude of business-to-consumer, business-to-business and intra-business options. It also offers new opportunities to intermediation and electronic communities, for example. However, these options need to be examined on a case-by-case basis, and different e-business investments cannot be properly examined using the same evaluation criteria.

– The economics of e-business are increasingly marked by Metcalfe's Law. Characteristics of virtual goods, information and the marketspace can drive costs down substantially. At the same time, costs of maintaining and developing sites into profitable operations have frequently been underestimated or not tolerated for a sustainable enough period.

– At the same time, information as a by-product of transactions can become a customer offering in itself. Information can be cheap to accumulate and highly profitable to exploit. It is sophisticated understanding of the complex and dynamic economics of such factors that determine the level of success achieved in e-business.

7.7 Practical action guidelines

– Identify where your different investments lie on the diagram depicting the eras in the IT industry revolution (Figure 7.1). Analyse the degree to which the evaluation regimes for these investments, and for future investments, appropriately capture the likely costs and benefits.

– Ensure that e-business investments, in particular, are not being limited because of unsuitable assessment procedures. Check against the suggestions for evaluation made in Chapter 8.

– Sensitize yourself to the changing economics that e-business applications can bring. Consider how these different opportunities can be identified and how your business could take advantage of them.

– Become aware of the risks and down-sides also inherent in moves to e-business. Learn to check these aspects, especially where commentators fail to raise these issues themselves.