E-valuation (2): four

approaches

8.1 Introduction

The large US Internet companies are overvalued by just over 30% assuming revenue grows at 65% compound, and overvalued by 55% using a 50% revenue growth projection.

Research finding by Perkins and Perkins,

The Internet Bubble (Harper and Collins, 1999)

E-business is such a wide-ranging phenomenon that there is something in it for everybody. The trouble is that it is not always obvious what's right for which company.

Willcocks and Sauer,

Moving to E-business (Random House, 2000)

In Chapter 7 we spelled out the e-opportunities and the underlying economics, while also sounding notes of caution where appropriate. In this section we put forward some ways in which the e-opportunities can be evaluated and grasped, including sustainable competitive advantage, differentiation analysis, real options and scorecard approaches. Before doing this, one issue we can deal with quickly is how to evaluate the Internet business itself.

The period 1998–2000 saw much ‘irrational exuberance’1 on Internet company stock valuations. One famous example saw Priceline.com, an auction-based travel agency, with a market value of US$7.5 billion in February 2000, while making losses of over US$150 million a year. Its value was presented as higher than that of United Airlines (yearly profit US$400 million) and Continental Airlines (yearly profit US$300 million) combined. The only real way to judge such valuations is to ask whether they represent reasonable expectations about the future growth and profitability of Internet businesses. Even on optimistic estimates of performance, Perkins and Perkins2 concluded that in 1999 the big US Internet companies were overvalued by 30%.

Higson and Briginshaw are correct in suggesting that we need to apply free cash flow valuation to Internet businesses in their start-up phases – a function of sales and the profitability of those sales3. Price/earnings and price/revenue multiples are not very revealing for early stage businesses. A company's free cash is its operating profit less taxes, less the cash it must re-invest in assets to grow. A company creates value when free cash flows imply a rate of return greater than the investor's required return, and that only happens when they can sustain competitive advantage in the markets they serve.

To model the cash flow of an Internet business, one needs to:

(1) forecast the future market size and sales;

(2) project the company's costs; and

(3) forecast the investment in the balance sheet (the company's asset needs) as it grows.

What matters, of course, are the assumptions behind these estimates. Higson and Briginshaw make the point that often the implicit assumptions have been that the competitive environment will be benign and that Internet companies will earn oldeconomy margins or better. They posit a much more strenuously competitive environment where ‘companies will need to be lean, nimble and constantly innovative . . . in such a world, the market keeps companies on survival rations, no better’.

Having looked at Internet stock valuation, let us now consider four approaches to evaluating businesses: analysis for opportunity and sustainability; real options, a scorecard approach and Web metrics. These are designed to complement and build on the ideas and approaches in previous chapters, all of which still apply in the e-world.

8.2 Analysis for opportunity and sustainability

Given the changing economics of e-business and accompanying high levels of uncertainty, it becomes even more important when evaluating it to focus on the big strategic business picture, as well as on issues such as Web site metrics and technical/ operational evaluation. In Chapter 3 we met the business-led approach and the five IT domains navigational tool. In our work we have found both approaches immediately applicable to the e-business world. More recently, David Feeny has extended his work into providing a set of matrices for evaluating the e-operations, e-marketing, e-vision and e-sustainability opportunities4. Here we will sketch the first three and focus more attention on the issue of e-sustainability.

E-operations – uses of web technologies to achieve strategic change in the way a business manages itself and its supply chain. The main opportunities here are in:

(1) automating administration;

(2) changing the ‘primary infrastructure’, that is the core business processes of the business, and achieving synergies across the company (e.g. sharing back-office operations or intranets);

(3) moving to electronic procurement; and

(4) achieving supply chain integration.

Feeny suggests that if the information content of the product is high, then the e-investments should be in primary infrastructure. Where there is high information intensity in the supply chain, then electronic procurement and integrated supply chain are the most obvious targets for investment. Where value chain activities are highly dispersed, then e-investments may be able to achieve high payoffs from introducing much needed synergies.

E-marketing – use of the technology to enable more effective ways of achieving sales to new and existing customers. The opportunities here are to enhance:

(1) the sales process (e.g. by better market/product targeting);

(2) the customer buying process (e.g. by making it easier to buy); and

(3) the customer operating process, enabling the customer to achieve more benefits while the product is in use.

Of course, one could take action on all three fronts, but much will depend on how firms are competing in the specific market, how differentiated the product/service is and could be, and how regularly customers purchase. The key here is to diagnose these factors and discover where an e-investment will achieve maximum leverage.

E-vision – using Web-based technologies to provide a set of services which covers the breadth and lifespan of customer needs within a specific marketspace. This means analysing where e-improvements can be made and where competitors may be weak in servicing the customer at all stages of the purchase process and beyond, in other words in all dealings the customer is likely to have with the business. The major iterative components of the analysis are:

(2) identify relevant providers;

(3) construct options for customer choice;

(4) negotiate customer requirement; and

(5) provide customer service.

Feeny points out that this vision of the perfect agent may seem too good to be true, but that firms are already moving in this direction. Thus, Ford's CEO is seeking to transform Ford into ‘the world’ world leading consumer company for automative service’, and this is already influencing the firm's acquisition policy and the levels of IT literacy for which it is striving.

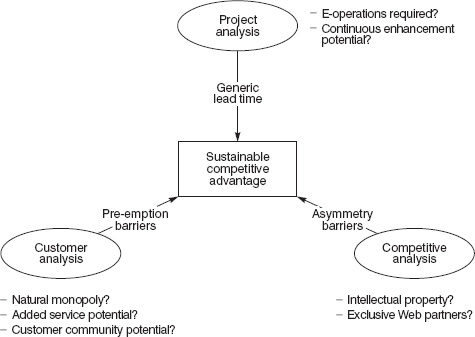

Beyond all these concerns, organizations also need to carry out a fundamental analysis of where sustainable competitive advantage comes from when utilizing Web-based technologies. Feeny's analysis suggests that there are three main sources of sustainable competitive advantage (see Figure 8.1).

The first component of sustainable competitive advantage is generic lead time. Being first into e-initiatives can offer a time advantage, but this has to be continually renewed and taken advantage of. Thus, generic lead time is widely considered to be the most fragile of the three sustainable competitive advantage components. However, although Web applications can be rolled out in weeks by followers, some aspects may not be replicated as quickly, for example IT infrastructure, and a business may also stay ahead by continuous technical enhancements that have business value.

The second component, asymmetry barriers, may come from competitive scope which a competitor cannot replicate, for example geographic spread or market segments serviced. They may be from the organizational base, reflecting nonreplicable advantages in structure, culture and/or physical assets, or from non-replicable information resources, in terms of technology, applications, databases and/or knowledge bases.

Figure 8.1 Evaluating e-sustainability components (adapted from Willcocks and Sauer, 2000)

The third component of sustainable competitive advantage is pre-emption barriers. In being first, a business needs to find an exploitable link in terms of customers, distribution channels and/or suppliers. It needs to capture the pole position through its value chain activity, creating user benefits and offering a single source incentive to customers. It also needs to keep the gate closed, for example by its application interface design, its use of a user database or by developing a specific community of users.

We will see these sustainability issues being played out in the indepth case study of Virtual Vineyards at the end of this chapter.

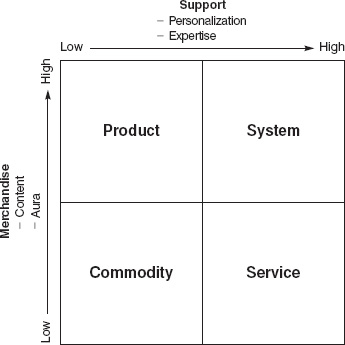

Figure 8.2 Sustaining the e-advantage through differentiation (adapted from Mathur and Kenyon, 1997)6

In moving to e-business, the practice of differentiation emerges as key to success. Our own findings suggest that in most sectors commodity-based, price-sensitive competition on the Web will not be an ultimately sustainable business model5. Mathur and Kenyon's work is particularly pertinent here, and its prescriptions have been seen in many of the leading B2C companies found in our research. What competes in the marketplace is what a customer sees as alternatives or close substitutes, in other words what the customer can choose instead6. A business enters the competitive arena with a customer offering – the inseparable bundle of product, service, information and relationship. The challenge over time is to continually differentiate and make this offering less price-sensitive in ways that remain attractive to the targeted market segment. The options are captured in simplified form in Figure 8.2.

The support dimension of an offering represents those differentiating features which customers perceive in the way the seller helps them in choosing, obtaining then using the offering. All other differentiating features belong to what is called the merchandise dimension. The merchandise features of a car sold over the Web would include its colour, shape, size, performance characteristics and in-car entertainment. Its support features would include availability of information, ease of purchase, the test-drive, promptness of delivery and service arrangements. The merchandise component can be further differentiated by augmenting content (what the offering will do for the customer) or aura (what the offering will say about the customer). Amazon can make available a wider range of books and products, whereas Merit Nordbanken can provide WAP phone access to a customer's account – both companies’ brands will augment the aura of the offering. The support dimension can be augmented by personalization (the personal attention and distinctive familiarity offered to each customer's needs) and expertise (the superiority displayed by the seller in the brainpower, skill or experience in delivering and implementing the offering). Federal Express facilitates personal Internet tracking of your parcel, whereas Virtual Vineyards offers on-line access to information on wine and to the expertise of a sommelier (see the in-depth case study, below). In our own work, we found leading organizations striving to leverage both collective sources of differentiation, not least leveraging information bases to get closer to and ‘lock-in’ customers.

What matters is achieving differentiation in a particular changing competitive context so that the dynamic customer value proposition (simplified in Figure 8.2 as commodity, product, service or systems alternatives) is invariably superior to what else is available to the customer. This may sound simple, but it is deceptive. It requires a knowledge of and relationship with customers, and a speed and flexibility of anticipation and response that many organizations have found difficult to develop, let alone sustain. Moreover, as many commentators observe, it has to be achieved in specific Internet environments where power has moved further, often decisively, in favour of the customer.

8.3 Real options evaluation of e-business initiatives

In finance, options are contracts that give one party the right to buy or sell shares, financial instruments or commodities from another party within a given time and at a given price. The option holder will buy, sell or hold depending on market conditions. ‘Real options’ thinking applies a similar logic to strategic investments that can give a company the option to capture benefits from future market conditions. Real option thinking applies particularly in situations where contracts are vague and implicit, where valuation models are much less precise, and where a real options investment can open out a variety of possible actions and ways forward.

As such, real options thinking might be appropriate when considering e-business/technology investments. The objective here would be to invest an entry stake, for example a pilot or a prototype, so as to retain the ability to play in potential markets and to change strategy by switching out of a product, technology or market. Clearly, real options thinking and analysis is most appropriate in conditions of high uncertainty, where much flexibility in future decisions is required – a good definition of the prevailing circumstances with regard to moves to e-business in the new decade.

The arrival of the Internet has increased the complexity of issues to consider when we invest in the technologies. Return on investment approaches can lead to under-investment and not adopting a long-term horizon. The most sensible, risk-averse route might be to build more options into the strategy, that is to invest in e-technologies in ways which create a variety of options for the future.

Kulatilaka and Venkatraman7 suggest three principles for pursuing real options analysis for e-business.

(1) Pursue possible rather than predictable opportunities. Opportunities in the virtual marketspace are anything but predictable. Using predictable, sector-bound models will miss out on many opportunities that are not obvious in their initial stages, and which may close, especially if competitors apply their learning from the sustainable competitive advantage analysis detailed above. Consider Microsoft, which in 1999 invested US$5 billion in AT&T, the largest US cable provider. At the same time, it invested US$600 million in Nextel, the US mobile services group, and collaborated with NBC to produce an on-line news site and television channel. These investments create many possible options for Microsoft's competitive future.

It is important to create at least three types of options. The first is to enable a company to be flexible about its scale of operations, for example allowing migration or scaling up of operations and business processes on the Web. The second is to create scope options enabling changes in the mix of products and services offered. Thus, Amazon has moved from books to videos and CDs and, because of its business model and investments, is able to incorporate other products. The third is timing options, allowing the company to be flexible about when to commit to particular opportunities.

(2) Explore multiple avenues to acquire your options. For example, real options can come from alliances and partnerships. The challenge is to move away from just adding business lines and those things that are easy to assess, towards the acquisition of capability options. Kulatilaka and Venkatraman suggest four different avenues for acquiring real options:

– entry stakes: options inside a company that allow it, but do not oblige it, to act (e.g. on-line brochureware and registration of a Web address);

– risk pooling: arrangements with external players through various forms of contract;

– big bets: major commitments, for example Toys R Us created a separate unit to expand on-line aggressively and Charles Schwab made major commitments from 1995 and is now the on-line market leader in its sector; and

– alliance leverage: establishing a portfolio of alliances in many areas, for example the Microsoft cited above.

(3) Structure the organization to unleash the potential of the digital business. Traditional organization structures may limit fast execution and continuous adaptation. What will need looking at, typically, is the provision of appropriate incentives for creating and developing digital businesses; the reorganization of information flows to respond in Internet time; and the ability to develop and contract dynamically for external relationships.

In summary, in many ways e-business investments are like R&D investments. In both cases the application of real options analysis may well produce much more value than for example the traditional net present value analysis (see Chapter 3). There are several effects in a detailed analysis that favour investments in supposedly more risky e-business projects, when valued using real option pricing methods.

(1) Net present value techniques are heavily dependent on the applied discount rate. In the case of risky e-business projects, these would be heavily discounted. In real options pricing, the use of risk adjusted rates is avoided.

(2) This effect is further strengthened by the long-time horizons that would need to be applied to R&D and many e-business investment decisions.

(3) Long-time horizons leave more time to react to changing conditions. The possibility of changing direction is taken into account in real options valuation, but not net present value calculations.

(4) The high volatility of the value of e-business or R&D outputs positively influences the option value because high returns can be generated, but very low returns can be avoided by reacting to the changing conditions. In net present value evaluations, high volatility leads to a risk premium on the discount rate and so to a lower net present value.

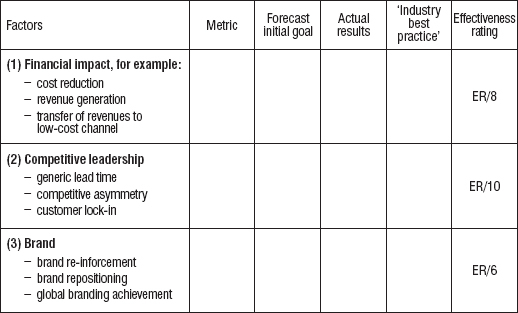

8.4 E-business: a scorecard approach

Work carried out by Willcocks and Plant8 and developed further by Plant9 has led to the development of a proposed scorecard approach for assessing an e-business on an ongoing basis. The principles that apply are very similar to those detailed in Chapter 5. However, the content of the scorecard has been refined as a result of our own research work into leading and lagging e-business practices over the 1998-2001 period. In particular, our work uncovered four types of strategy that leading e-businesses went through in their evolution. The four are ‘technology’ (superior technology application and management), ‘brand’ (the business use of marketing and branding), ‘service’ (the use of information for superior customer service) and ‘market’ (the integration of technology, marketing and service to achieve disproportionate profitability and growth). In terms of business value, there turned out to be good, and less effective, ways of conducting each strategy.

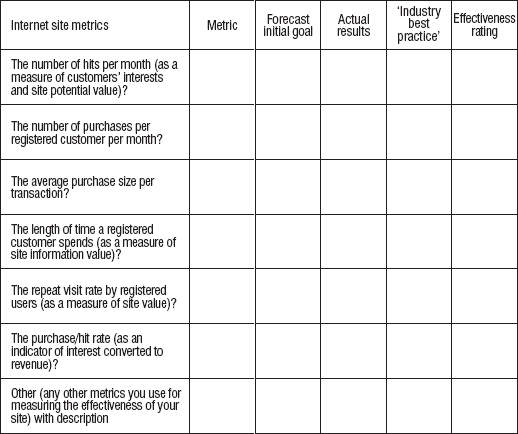

With this in mind, we can build a scorecard approach using the following procedure, adapted from Plant (2000)9.

(1) Assess performance according to seven factors:

– financial impact;

– competitive leadership;

– ‘technology’ achievement;

– ‘brand’ achievement;

– ‘service’ achievement;

– ‘market’ achievement; and

– Internet site metrics.

(2) Develop an effectiveness rating scale, for example 1–10.

(3) Develop the detailed metrics.

(4) Establish goals, results, ‘industry standard’ and effectiveness rating.

(5) Make individuals responsible for results and incentivize them to deliver.

(6) Decompose criteria to ownership, process and transaction levels.

(7) Automate the evaluation system for real-time accurate management information.

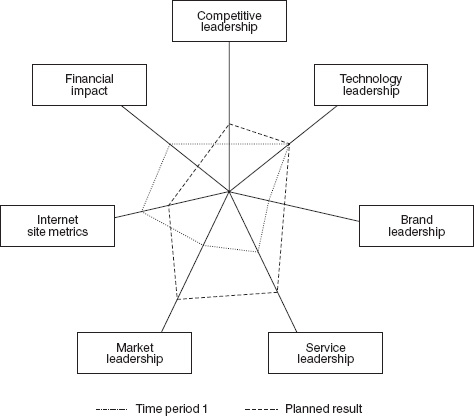

By way of illustration only, Figures 8.3, 8.4 and 8.5 show what such a scorecard could look like at the fourth stage of development. In the effectiveness rating column we show, again as an illustration only, that effectiveness on each dimension may also include a weighting element.

Figure 8.3 A scorecard approach – 1

Finally, as a way of summarizing the findings on a regular basis, Plant suggests the use of an effectiveness rating polar graph. An illustration of what such a graph would look like is provided in Figure 8.6.

Figure 8.4 A scorecard approach – 2

Figure 8.5 A scorecard approach – 3

This section has indicated that the balanced business scorecard concept and its underlying principles as detailed in Chapter 5, have considerable applicability in the e-business world, but that detailed tailoring, and the development of new quadrants and specific metrics, are necessary – something we also highlighted for other IT-based applications of the scorecard.

8.5 Web metrics and the one that matters

In the previous section we detailed a scorecard approach which included a separate evaluation area for Internet site metrics. At the operational level, there has been much interest in Web metrics, that is how the performance of a Web site can be evaluated. From the earliest days of transactions on the Web through to 2001, there has been an evolution towards metrics that are more meaningful in business terms. There have been perhaps six stages in this evolution:

Figure 8.6 An effectiveness rating polar graph

(1) ‘hit rate’ – requests for data from a server;

(2) ‘page view’ – number of HTML pages served to users;

(3) ‘click-through’ – percentage of people responding to an online advert;

(4) ‘unique visitors’ – total number of individuals visiting;

(5) ‘percentage reach’ – percentage of sampled users visiting a site page each month; and

(6) ‘new breed’ – in the light of the inadequacies identified above, evaluations have taken on measures such as length of stay, number of registered users, number of repeat visits, site behaviour and return on investment.

All these measures generate information, although the usefulness of that information depends on what business purpose it can serve. In all too many cases information has been generated with no great evaluation payoff; in fact, worse still, it has probably contributed to an information overload and lack of clarity. In all this, one abidingly useful measure is the conversion rate, which can be defined as that percentage of visitors who take the desired action, for example purchase the item at a price that generates profit. Such a measure contributes to understanding the real business value of the Web site.

Using the conversion rate as a major control parameter is important for a number of reasons. Firstly, small changes in the conversion rate can produce large gains (or losses) in business value. Average conversion rates on the Web still come in at between 3 and 5%. However, consider the maths. For one company that failed in 2000 it was costing US$13 million to get 100,000 customers (US$130 per customer). Average sales were US$80 a time. The conversion rate was a very poor 1.5%. Instigating policies to push the conversion rate up just another 1.5% would probably have seen the company in profit.

Secondly, the conversion rate reflects important qualitative aspects that are not otherwise easily captured. Thus, easy-to-use interfaces have high conversion rates. Sites that are slow or dragged down by site errors or time-outs have low conversion rates. Frequent users value convenient sites, for example Amazon's one-click service, and this drives up conversion rates. Low conversion rates may also indicate that clever advertising and high click-though rates are not converting into effective advertising. High conversion rates may also indicate the extent of word-of-mouth, which is the most powerful and cheapest form of advertising. Sites with good user interfaces, that are fast and convenient, with great service, attract this form of advertising and high conversion rates.

Having stressed the importance of adopting the conversion rate as a method of evaluating Web site performance, it would be remiss not to spell out some of the issues that need to be dealt with when using conversion rate as a metric. Firstly, conversion rates will be low for new customers and higher for returning customers. Watch them both and the blended rate. Secondly, be aware that seasonality affects the conversion rate. Thirdly, always also keep an eye on profitability. Do not rent customers by cutting prices too long to drive up conversion rates. Into 2001, Egg, the UK-based on-line bank, has many customers and a strong conversion rate. Even so, its pricing strategy has been described as ‘giving away £10 in order to gain £5’, and it was still making losses.

8.6 In-depth case study: Virtual Vineyards (subsequently Wine.com)

Virtual Vineyards (V-V) is a prime example of a company that created a new kind of offering for an old product, by enhancing the information and the relationship dimension of selling wine. V-V was established in California in January 1995 by Peter Granoff (a master sommelier) and Robert Olson (a computer professional). Olson believed that there was a market on the Internet for high-value, non-commodity products. The product was chosen according to three criteria:

(1) the information on point of sale should influence buyers’ decisions;

(2) the product should be customizable; and

(3) expert knowledge should offer added value if bundled with the product.

Clearly, he wanted to find a product rich in information content, so as to be able to take advantage of IS capabilities. Eventually, he decided to market and sell Californian wine from small producers. The structure of the distribution channel had left small producers isolated and Olson saw an opportunity there. Granoff, an expert in wine, liked the idea and the two formed Net Content Inc. Virtual Vineyards (V-V) was the company's first Web site, but it soon became synonymous with the company.

Californian wine dominated the US market, accounting for three-quarters of the total volume of wine sold. The US market had been shrinking over the previous ten years, but there were signs of recovery. V-V targeted the higher end of the market, which consisted of people who appreciated good wine, were interested to learn more about it, were willing to pay a premium for a bottle of fine wine, but who were not connoisseurs, and therefore could benefit from the knowledge of an expert. Along with a wide selection of wines from small producers, V-V offered information about wine and its history, ratings and descriptions of all the wines it sold, and personalized answers to individual questions and requests. The site was a quick success on the Internet attracting thousands of users and increasing revenues at a fast pace.

As a virtual company, Virtual Vineyards’ business idea has been fundamentally tied to the Internet. The case provides an excellent opportunity to demonstrate how competitive positioning frameworks can be used to evaluate e-business investments at both the feasibility and post-implementation stages. Here the company's strategic positioning will be assessed relative to its use of the Internet. Although the business idea is the most important characteristic of every venture, a strong business idea may fail, if not properly supported by IT. This is especially true in the case of Internet companies, where IT is pervasive to the organizational structure and daily operations.

Assessing V-V: using five forces analysis

Michael Porter has suggested that an organization needs to analyse its positioning relative to five industry forces in order to establish its competitive position. These are its buyers, suppliers, competitors, the threat of new entrants, and the threat of substitutes.

Buyers

The targeted market was defined as ‘people interested in a good glass of wine, but not wine connoisseurs’. Clearly, V-V adds value to the consumer by providing guidance through suggestions and ratings. Once the buyer has accepted the authority of V-V, he/she has surrendered bargaining power. The endless variation of wine and the specialized information associated with that make it practically impossible for the buyer to make comparisons among the various wine catalogues/ratings, etc. Even though the buyer has many choices, he/she has not the necessary knowledge and information to make the choices. Therefore, the key issue is reputation.

Once established, it gives a decisive competitive advantage to the virtual intermediary. The relationship with the customer is strengthened by repeating orders that lock in the consumer and reduce even more his/her bargaining power; as long as the customer is satisfied with the offering (i.e. gets good wine at a decent price and enough information to satisfy his/her need for knowledge), there will be no real incentives to switch. Price, although always important, is not a decisive parameter of the offering. The buyers who are prepared to pay the premium to ultra-premium price perceive the product as highly differentiated, and therefore are less sensitive to price and more concerned about value. The offering is not easily comparable to alternative ones, and therefore V-V has found a source of information asymmetry which protects it against the price competition that electronic markets introduce.

Suppliers

In the USA there are hundreds of small vineyards, mostly in California. The distribution channel is dominated by few large wine distributors, leaving the small producers without proper access to the consumer, either directly or through retail outlets and restaurants. The costs of direct marketing or establishing relationships with retail outlets is rather high for a small producer and an intermediary may be more efficient, as it can achieve economies of scale. The intermediary represents a number of small producers to the retailers and can establish better relationships through volume and variety. At the same time, the client can enjoy one-stop shopping for a variety of wine. Most of the producers, with the exception perhaps of a few established brands, have little bargaining power.

The market targeted is people who appreciate good wine, but they are not connoisseurs with specific needs; therefore, a bottle of wine from one producer can easily be substituted for another with similar characteristics and quality. A powerful intermediary, with an established reputation among customers, has more bargaining power than the numerous small suppliers, as the case of the large wine distributors has demonstrated. That does not mean that the various vineyards are desperate for distribution channels. Many vineyards that produce a small number of bottles annually have established the necessary relationships with bars, restaurants and speciality shops, and distribute their production through those channels. At the same time, in an industry were the product has high aura, reputation is important for producers as well. Reputation for wine is developed and maintained mainly through ratings, positioning in shelves and pricing. It takes a long time for a producer to establish reputation and, therefore, vineyards are cautious as to whom they sell their wines, for fear of harming their reputation. However, if an intermediary is regarded as knowledgeable and impartial, then it can build relationships based on trust with enough suppliers so that they have little bargaining power on an individual basis.

Large producers dominate the market, and are more attractive to distributors, as their nationally established reputation allows a higher profit margin. Small producers are selling either directly to consumers (direct mail or the Internet) or to restaurants and speciality shops. Distributors sell to restaurants, speciality shops and supermarkets. Off-premises sales account for 80% of the wine volume sold to consumers. Supermarkets account for 70–80% of that volume. As mentioned before, most of that wine comes from the large producers through the distributors.

Competitors

In order to identify V-V'V competitors, we will examine what consumers see as alternatives. V-V sells directly to consumers for home consumption and therefore compete with other offpremises points of sale. V-V does not compete with supermarkets as they address a different kind of consumers and price range. Nevertheless, it may attract a small portion of the upper end of supermarket clients who would like to know a little bit more about the wine they buy, but do not have the time or the desire to go to speciality shops.

Compared to any direct mail catalogue, V-V is more up-to-date and interactive, and it delivers more and faster (although not in all cases), information, which is better presented and may be customized. All these are the inherent potential characteristics provided by the Internet. In addition, it offers a larger variety than mail order catalogues compiled by specific producers. The market addressed is more likely to have Internet access and appreciate expert advise to help (guide) their choice. V-V has a clear advantage over direct mail.

V-V competes with other Internet sites, mainly maintained by small producers or wine shops. V-V offers more variety than any small producer, and more guidance and information than the wine shops sites. Therefore, it has an advantage over both.

V-V'V main competitors are the shops specializing in selling wine. They target the same consumer group and both add value through information and guidance. IT allows V-V to offer more services, such as information and ratings about every wine and a comparative lists of ratings, prices, etc. Some people may prefer the face-to-face contact with the expert sommelier in the shop, whereas others may feel uncomfortable with that and prefer the personalized answer through email at V-V. Until more data is available, it is difficult to predict the outcome. However the revenues from sales from the first few months of operation suggest that V-V has found a robust market niche.

Threat of new entrants

This is a serious potential threat for V-V. New entrants, especially other Web sites, may emerge quickly from nowhere. It will be examined later, using more appropriate tools, whether and how V-V could achieve a sustainable competitive advantage.

Threat of substitutes

The market for wine is a subset of the market for alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages. Therefore, soft drinks and distilled spirits may be regarded as potential substitutes. Those products have less information content, are perceived as less differentiated than wine, consumers tend to make the decisions themselves and are less willing or have fewer incentives to experiment with alternative products. The market is dominated by few brands which control marketing and distribution channels. The structure of those channels is totally different from the wine market. In any case, customers do not need expert advice to make their buying decisions and therefore those products are not suitable for V-V.

There is a favourable position in the market for wine from a virtual speciality retail outlet. The product is rich in information content and the buyer's decision can be affected at the point of sale. Suppliers have limited power, as well as buyers.

The threat of substitute products is more apparent as the market seems to shrink, but this may even work in favour of V-V for a number of reasons.

(1) V-V has few physical assets and very low-cost operations. Therefore, its competitors may be affected first leaving potentially a larger market share for V-V to capture. A bigger market share suggests a higher reputation for V-V, which in turn would increase its bargaining power.

(2) The bargaining power of suppliers is reduced even more. As demand is smaller than supply, wine retailers and distributors have more choices to buy wine and can achieve better prices. Even if V-V does not want to attack prices, it can achieve better relationships, and therefore a greater variety, better wines or exclusive deals, by allowing producers a bigger profit margin.

(3) Although the V-V site specializes in wine selling, Net Contents (the company that owns the site) specializes in Web technology and marketing. Once the technology is in place, it can be used for a variety of purposes by finding new markets and products. The experience of V-V in Internet marketing will also be valuable. Of course, V-V'V success is not based primarily on the technology. Having the right content for the right market and establishing relationships with suppliers and buyers are more important aspects of V-V'V success than technology. In any case, those are also the potential sources of sustainable competitive advantage for V-V, as the technology can be copied easily.

(4) Knowing the market for wine is an important asset for the company. While the US market was shrinking during 1986–1994 the European market did not seem to be affected. V-V had many options to address other markets, perhaps more options than other retailers. Reaching customers is far easier due to the global reach of the Internet. Moreover, V-V'V reputation on the Internet is more international, compared to competing physical distributors, which have local (speciality shops) or national (distributors or chains) reputation. The technology could easily be transferred and even translated into other languages for a small cost. Given that, V-V had various choices for expanding to other markets. For example, it could decide to export Californian Wine, or take advantage of the European Union and establish similar operations in Europe with French (and perhaps Italian, Spanish, Bulgarian or Greek) wine or assess the potential of the Australian market, which has many producers of fine wine. The point is that by building a US business, V-V establishes an international reputation at no extra cost. Moreover, the front store (i.e. the Web site and logistics) operations and the relationships with customers can instantly be transferred anywhere in the world. Export restrictions and laws should be investigated, but V-V can still take advantage of the loose Internet legislation. Indeed, V-V has recently expanded its operation to include wine from more countries and to export to many countries.

Sustainable competitive advantage analysis

The analysis above showed that V-V has achieved a competitive advantage by making successful use of the Internet and Web technology. The case of V-V will now be analysed using the Figure 8.1 framework in order to determine sustainability of the competitive edge it has achieved. The framework addresses three questions.

(1) How long before a competitor can respond to the idea of V-V? Source of advantage: generic lead time.

(2) Which competitors can respond? Source of advantage: competitive asymmetry.

(3) Will a response be effective? Source of advantage: preemption potential.

How long before a competitor can respond?

The technology behind an Internet project such as that of V-V is rather easily replicated. As the Internet becomes more popular, software companies build applications that facilitate setting up a virtual shop. As a pioneer, V-V had a technological disadvantage, as it actually had to create much of the necessary software needed for its operations and solve problems of design and integration. With universities and corporations experimenting in similar areas, V-V could not expect its technology to be unique or to protect the firm against competition. On the contrary, the longer a competitor waited, the easier and cheaper it would be to set up a similar virtual operation. Applications were also easy to copy. A great deal of thinking is needed to come up with innovative ideas about service to customers, but it is a matter of few days before a skilled developer can copy them.

It is important here to make the distinction between IT and IS. Although the technology and applications would be easy to replicate, IS consists of more than the technology that enables it. Databases are a key component of IS – mainly the customer and wine databases.

The customer database is a proprietary, key asset that cannot easily be replicated by any potential competitor. Once the V-V site was launched, it was essential to try to capture as much of the targeted customer base as possible. Once customers start to buy from V-V, IT can be used to help lock them in. Locking in customers is the result of IT enabled services to the customers that have visited the site. New entrants have to deliver far more value, offering superior service at a considerably lower price in order to provide incentives for buyers to switch. A follower would have difficulty in offering a superior service, as that would require vision and thinking from scratch. Moreover, differentiation on service is based largely on the number of customers on the database and the individual history of each customer. Based on a customer's history, V-V can develop software to offer a personalized service and, therefore, incur switching costs.

On the other hand, a price war would not necessarily be effective for a series of reasons.

– Prices are not immediately comparable because of the high degree of perceived differentiation of the product.

– The targeted customers are not very price sensitive, as they are prepared to pay premium prices for quality wine. They are more interested in having the necessary information to make their decisions. This requires a database of wine information and ratings. A competitor could certainly create a similar database, but this would take a lot of time and resources.

– V-V could take advantage of the lead time to establish its reputation and authority both to consumers and producers. Building good relationships with producers, could result in exclusive deals with some of them. Moreover, if the producer is offered a good deal, both in profit and promotion terms, a partnership evolves and the producer has little incentive to move to another virtual distributor.

Generic lead time gives V-V the following potential sources of sustainable competitive advantage:

– established reputation;

– customer database;

– lock-in of customers by offering personalized service in conjunction with the databases; and

– building of partnerships.

However, project lifecycle analysis also suggests that V-V should expect its technology and applications to be copied easily by potential competitors.

Which competitors can respond?

A new entrant who tries to imitate V-V'V virtual site on the same market would appear to have no means to offer superior value and, therefore, give incentives to customers to switch from V-V, as it cannot match the potential sources of sustainable competitive advantage. However, the potential sources of sustainable competitive advantage for V-V, if examined carefully, reveal that they are specific to the US market. Although virtual as a company, V-V cannot take full advantage of the global reach of the Internet, because its products are tangible and, therefore, they are not as easily accessible outside the US. The geographical scope of V-V'V operations present boundaries to the potential sources of competitive advantage. Outside this scope, a new entrant is not very handicapped. This suggests a general Internet strategy – try to lock-out competition by taking advantage of local markets.

An existing competitor may already possess similar sources of sustainable competitive advantage. For the US wine distribution market those may be:

– large producers with established reputation and partnerships;

– mail order catalogues with large customer and wine databases, as well as perhaps an established reputation;

– speciality shops, known to wine connoisseurs and with established relationships with producers, can expand their operations on a national level; and

– distributors wishing to integrate forward and access customers directly.

From these potential threats, it is mail order catalogues that appear to have the necessary resources to counterbalance V-V'V competitive position, as their function is similar. Speciality shops could also take advantage of their knowledge base, established reputation (even though it is usually local) and relationships with producers. Distributors are not very likely to want to integrate forward, as they would move out of their core business with doubtful results. They might want to take advantage of Internet technology to make their business more efficient, but that does not concern competition with V-V, unless V-V decides to address restaurants and supermarkets, playing the role of distributor. Again this may be outside the core competence of V-V, as professionals tend to experiment less with wine, preferring repeated big orders of few wines.

Another source of competitive advantage comes from V-V organizational base. IT enables a very cost-effective, small and efficient organizational structure. In addition V-V has very few physical assets and none is tied to the business.

Will a response be effective?

Supply chain analysis reveals whether the potential sources of competitive advantage can ensure sustainability for the prime mover. V-V had successfully identified a beneficial point within the supply chain. This would be defined as being the link between the numerous small producers of quality wine and the market group that appreciated good wine, that was keen to learn more about it and was prepared to pay a small premium to get it, but did not have the specialized knowledge required to make the selection.

Although the need for such a link existed, the current structure of the distribution channel inhibited such arrangements. IT and specifically Internet technology could help establish that link in a cost-efficient way. This is in accordance with the second step of the model which consists of seeking the appropriate IT applications that would establish unique and superior relationships. According to the model, once V-V had established the relationships, it was threatened only by clearly superior offerings. Indeed, this is in agreement with the findings of the complete analysis of the case.

The next step suggests the use of IT to incur tangible and intangible switching costs. Associated costs are related to the application interface, the database and the community of users. In the specific case the interface is not of primary importance. An intuitive and easy-to-use interface could be designed by any competitor which allocated the necessary (comparatively few) resources. However, intangible switching costs may result by the sophisticated use of the customer and wine databases. A high quality of personalized service ties in the customer.

Case learning points

– Strategic frameworks, in particular five forces analysis and sustainability analysis have considerable applicability to the e-business world.

– The robust nature of the business model, arrived at through customer lifecycle analysis and the analysis and development of sources of differentiation, helps to explain much of V-V'V successful development, in terms of strategic positioning.

– V-V did not take a real options approach, but nevertheless its positioning allows it to go into complementary markets with the same customer base. Subsequently, it entered the on-line gourmet food market segment.

– The sources of sustainable competitive advantage would appear to be information- and people- rather than technologybased – something we have found in parallel research studies. V-V specialized in being very customer-focused, knowing its customers best, and also in securing long-term relationships with suppliers and distributors.

8.7 Summary

Most extant evaluation approaches can be utilized with e-business investments, but invariably they have to be modified, sometimes considerably, to take into account the changing economics of e-business and the high levels of uncertainty in the marketplace. Strategic, business-focussed evaluation approaches provide key steering mechanisms. At the same time, real options analysis is a complementary approach that can build much-needed flexibility into the assessment and mitigate the risk of missing future options made possible by the potential that Web-based technologies offer. Operationally, as ever, it is important not to get bogged down in evaluation metrics that ultimately may not provide useful information for management purposes. Select a few key, strong indicators, one of which is the conversion rate, and analyse carefully what they are telling you.

8.8 Key learning points

– Many of the modes of analysing the alignment of IT investment to strategic positioning (as detailed in Chapter 3) can still be applied in order to develop the e-business case. However, costs and benefits analysis will vary substantially from other types of IT investment. This has considerable implications for existing IT investment procedures and criteria.

– It is important to get behind the optimistic scenarios widely generated about Internet use. The research shows downsides and lack of clarity in important areas in the economics of e-business. Develop the business case thoroughly; make optimistic, realistic and pessimistic scenarios for the costs and benefits. Risk analysis and management as detailed in Chapter 3 must remain central to the evaluation and structure the way development and implementation proceed.

– When assessing the value of an Internet business in its startup phases, use free cash flow valuation – a function of sales and the profitability of those sales. Price/earnings and price/ revenue multiples are not very revealing for early stage businesses.

– One can make business sense of the e-opportunity by analysing the possibilities in terms of operations, marketing and the ability of Web-based technologies to support transformation of the business. Once this has been accomplished, it is necessary to evaluate how sustainable competitive advantage can be achieved – by maintaining generic lead time, by building asymmetry barriers and by exploiting preemption potential.

– Consider real options thinking for strategic management of e-business investments. Real options thinking and analysis is most appropriate in conditions of high uncertainty, where much flexibility in future decisions is required – a good definition of the prevailing circumstances with regard to moves to e-business in the new decade.

– A balanced business scorecard approach – suitably tailored and informed by research into leading and lagging e-business practices – can be applied to e-business investments.

– In building Web metrics, focus particularly on the conversion rate – be aware of what it does and does not tell you.

8.9 Practical action guidelines

– Stop using existing IT evaluation approaches merely because they have seemed to work for you in the past. Re-analyse how useful they are when applied to the realities of e-business in the new millennium.

– Use free cash flow as the dominant target for assessing the value of your e-business.

– Look at evaluating e-business opportunities in new ways, using strategic analysis frameworks especially developed for this purpose.

– Look to use a balanced scorecard approach but, as ever, the metrics depend on what you are trying to achieve, and what research highlights as the issues on which to focus.

– Do not allow Web metrics to become over-administrative and ultimately unhelpful. Find the key, credible and most informative metrics for the Web site performance of your particular business.

– Regularly revisit the analysis of your e-business investments, using, for example, the five forces and sustainable competitive advantage frameworks.