Perennial issues:

from infrastructure

and benchmarking

to mergers and

acquisitions

9.1 Introduction

Focusing on infrastructures you have to support the efficiency world because that's your life line . . . But on the other side you have to be innovative otherwise you have a grey image and the business people don't want to visit you even for their basics.

Jan Truijens, Senior IT Manager, Rabobank

I can make you appear as the best ski jumper, it's just a question of who I choose as a comparative base . . . if you tell me you know nothing about ski jumping, we just have to find a comparative base where people know even less.

President of an IT benchmarking service

It was the challenge of instability (from the merger) that has caused us to actually understand what's important to the business and put in place some of these measures. I think our focus has increased tremendously.

Mike Parker, Senior IT Manager, Royal & Sun Alliance

This chapter will address a number of key, perennial issues that either derive from technology evaluation or affect an organization's ability to conduct evaluation. All of these issues are highlighted regularly in journals, trade magazines and the news. Without consideration of the following issues, the IT evaluation story would be an incomplete one:

– IT infrastructure measurement issues;

– quality and the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM);

– benchmarking;

– cost of ownership;

– the effect of mergers/acquisitions on technology rationalization; and

– the Royal & SunAlliance case study, illustrating these key issues being played out in a specific organizational context.

9.2 IT and e-business infrastructure

The following organizations demonstrate a variety of perspectives on the management of infrastructure investments.

– In Hewlett Packard's Test and Measurement Organization, infrastructure investments are derived from business strategy. A senior IT manager explains that ‘looking first at the business strategy would drive solution investments which would then drive a required infrastructure, which would drive the computer centre charges to support it, and so forth’.

Moreover, ‘the infrastructure is usually not based on a return to the business in the more traditional sense. Not because we don't want to, but more because nobody really knows how to do it.’

– Unipart made a major investment in its desktop and networked environment in the mid-1990s. This was not costjustified. This has been perceived as a sound investment, the value of which no one questions. Since then, policies and standards have been established which allow lean upgrades of desktop and network infrastructures without requiring many individual financial justifications. These policies and standards are updated regularly in line with technological developments and changing business needs.

– Safeway, the UK-based retailer, continually opted for the ’simple’ infrastructure solution, differentiating it from many other organizations. In addition, the prototyping approach that is often adopted by Safeway to learn about the feasibility of a business idea implemented with technology prevents unnecessary large-scale investments in infrastructure which could, otherwise, go unused. According to former CIO Mike Winch, ‘My view has always been that if the business case is good, then even average to bad technology will work well. If the business case is bad, the best technology in the world will not do a thing for you. So let us concentrate on how we can drive the business forward and don't let's spend lots of time looking at the technology.’ Ultimately, Safeway has stood by its IBM investments with DB2 as its lone database product:

It means we've got a lot less technology, a lot less skill required, and it's cheaper. Take the Compass award, for example, which measures the cost effectiveness of service delivery. We have constantly outperformed all our competitors and one year out-performed the whole of Europe and most of North America as well. We didn't set out to be the cheapest, but strangely we are. We did however set out to be very uncomplicated, you can therefore relate cost performance with simplicity. If proof is needed everyone wanted to declare how much they were going to spend on doing the Millennium. Again, one of our competitors said they were going to spend £40–50 million, we spent £5 million.

Technological infrastructure needs within an organization expose the weaknesses of any evaluation system and test the ability of the organization to take a comprehensive look at investments. Infrastructure is the prime example of an IT investment which has no obvious business benefits, as the benefits are derived from whatever applications are built upon the infrastructure.

All the organizations we studied that addressed infrastructure issues struggled with the same issues:

– the need to justify infrastructure investments in light of the intangible nature of infrastructure benefits;

– the definitive need to invest in infrastructure regardless of the outcome of evaluation;

– the trade-offs inherent in infrastructure investments; and

– the need to invest in infrastructure in ways that rolled all issues – legacy systems, ERP (enterprise resource planning) and moves to e-business – into a common flexible infrastructure that could support the business, even when its needs were uncertain two years hence.

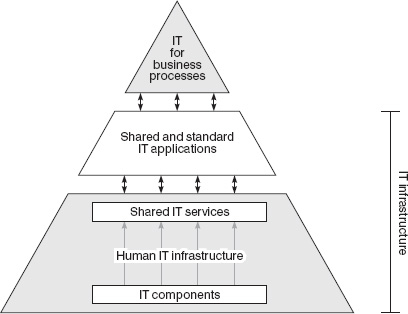

Sauer and Willcocks1 suggest that IT/e-business infrastructure investments must, in the base case, be dictated by and aligned with business strategy. In other words, IT infrastructure is the metaphorical and physical platform upon which business processes and supporting technology rest. However, different business strategies and long-term goals dictate different types and sizes of investment in the IT infrastructure. Figure 9.1 paints the picture of the elements of IT infrastructure derived from research by Weill and Broadbent2. At the base are IT components, which are commodities readily available in the marketplace. The second layer above is a set of shared IT services such as mainframe processing, EDI (electronic data interchange) or a full service telecommunications network. The IT components are converted into useful IT services by the human IT infrastructure of knowledge, skills and experience. The shared IT infrastructure services must be defined and provided in a way that allows them to be used in multiple applications. The next building block shown in Figure 9.1 are shared and standard IT applications. Historically, these applications have been general management applications such as general ledger, budgeting, but increasingly strategic positioning drives the adoption of applications for key business processes.

Figure 9.1 Elements of IT infrastructure (adapted from Weill and Broadbent, 1998)2

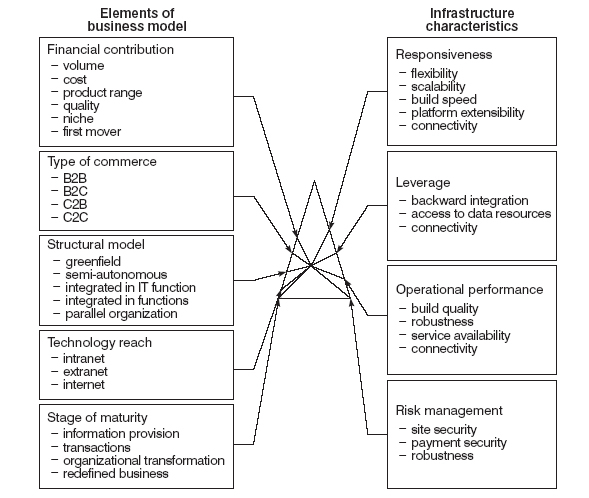

Figure 9.2 Prism model for analysing e-business infrastructure characteristics

Another perspective is provided by Sauer3, who has developed a prism model for capturing the possibilities that need to be evaluated in designing an e-business infrastructure (Figure 9.2).

Weill and Broadbent suggest that strategic context, or changing business demands, can be articulated through the use of ‘business maxims’, based on the following categories:

– cost focus;

– value differentiation perceived by customers;

– growth;

– human resources; and

– management orientation.

From the business maxims are derived IT maxims with regard to:

- expectations for IT investments in the firm;

- data access and use;

- hardware and software resources;

- communications, capabilities and services; and

- architecture and standards approach.

These will ultimately help to clarify the firm's view of infrastructure. In their study of 30 firms, Weill and Broadbent observed the following four different views of IT infrastructure and the likely results.

(1) None – no firm-wide IT infrastructure, independent business units, no synergies. Expected outcome: forgo any economies of scale.

(2) Utility – IT seen as a utility providing necessary, unavoidable services which incur administrative expenses. Expected outcome: cost savings via economies of scale.

(3) Dependent – IT infrastructure a response to particular current business strategy. Derived from business plans and seen as a business expense. Expected outcome: life of strategy business benefits.

(4) Enabling – IT infrastructure investment integrated with strategic context. Enables new strategies and is influenced by strategies. Seen as a business investment. Expected outcome: current and future flexibility.

A ‘dependent’ view indicates that infrastructure should respond primarily to specific current strategies; an ‘enabling’ view means that over-investment in infrastructure should occur for longterm flexibility. The enabling view is that specified by Jan Truijens of Rabobank in his description of the trade-off between efficiency and flexibility, as can be seen in the following case study.

– In the early 1990s, Holland's Rabobank decided it required new, up-to-date client–server architecture. In 1995, after a great deal of human and financial resources were applied to the conversion, Rabobank wrote off the already significant investment in the project. Simply put, the bank had pursued client–server with no serious evaluation performed and no knowledge base within the organization upon which to manage the project. Since that time, Rabobank has paid more attention to the evaluation issues specific to infrastructure investments. Everyone has infrastructure, says Truijens, one of the team of architects of the restructuring, so the issue cannot be ignored. According to him:

There are various ways of looking at infrastructure: there is the ‘efficiency’ approach, the search for effectiveness, and there is the enabling concept, putting new infrastructure in place to ease innovations in business. But the way we analyse these type of things isn't the way you can analyse other technology investments. So to look forward you have to do some scenario thinking, otherwise if you are looking at your business plans well there's only one plan.

In other words, Truijens suggests that the way to develop infrastructure is to consider different scenarios, the sorts of options the organization might want to consider as a business in the future and what infrastructure will be flexible enough to support these very different possible options.

Truijens provides insightful observations on the trade-offs inherent in infrastructure investments: a fundamental one is the trade-off between efficiency and flexibility. Increased efficiency in architecture decreases flexibility. Yet flexibility in infrastructure is a requirement for innovation:

The enabling part is the difficult part. Focusing on infrastructures you have to support the efficiency world because that's your life line, that's a condition you have to address unless you have no constraints financially or no interest in internal customers and prices and such like. So you have to do your basics well. But on the other side, you have to be innovative otherwise you have a grey image and the business people don't want to visit you even for their basics. All these things are projected into your architectures. And also in the organizational part of the infrastructure which is of course complementary to the technical aspect in IT.

Weill and Broadbent pass no judgement on whether any one of these views is ‘best practice’. Their case research shows that the important objective is to ensure that the view of IT infrastructure is consistent with the strategic context of the firm/ organization. For instance, consider a firm with limited synergies amongst its divisions and its products. In this situation, no one IT infrastructure is consistent with the highly divisionalized nature of the firm, where the locus of responsibility is as close as possible to each specific product. Lack of centralized IT infrastructure was seen as providing greater freedom to the divisions to develop the specific local infrastructure suited to their business, customers, products and markets – a phenomenon we found in the highly diversified UK-based P&O Group.

On the other hand, Broadbent and Weill researched a chemical company which sought different business value from its IT infrastructure investment, namely cost reduction, support for business improvement programs and maintenance of quality standards. The emerging focus on customer service, where business processes were more IT dependent, was resulting in a shift toward a ‘dependent’ view of infrastructure.

On average, the ‘None’ view will have the lowest investment in IT relative to competitors, and will make litttle or no attempt at justification of IT infrastructure investment. The ‘Utility’ view will base justification primarily on cost savings and economies of scale. The ‘Dependent’ view is based on balancing cost and flexibility and this will be reflected in the justification criteria. An ‘Enabling’ view will have the highest IT investment relative to competitors and investment in infrastructure will be well above average. The focus of justifying IT infrastructure investments will be primarily on providing current and future flexibility. The work of Weill and Broadbent provides a highly useful conceptualization of infrastructure investment approaches, when they are appropriate, and the evaluation criteria which will drive their justification.

Sauer and Willcocks have extended this work into looking at investments in e-business infrastructure4. They found that infrastructure investments now need to be a boardroom issue if moves to e-business are really going to pay off. They point to the many e-business disappointments recorded up to 2001 due to failure to invest in the re-engineering of skills, technologies and processes needed to underpin e-business. One of the key findings has been that increasingly businesses need to invest in the ‘Enabling’ form of e-infrastructure, and that the other forms identified by Weill and Broadbent in 1998 may well be too restrictive for moves to e-business.

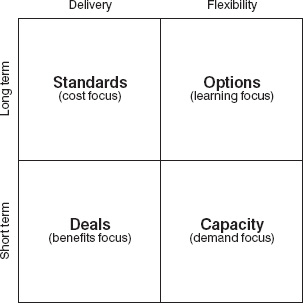

Another infrastructure evaluation tool has been suggested by Ross et al.5 They identify a set of trade-offs companies typically make in establishing their e-business infrastructure. They posit four approaches based on different emphases (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Infrastructure management trade-offs

Companies focusing on delivery in the short term will tend to take a ‘deals’ approach, including for example dealing with a variety of technology providers. This could well be at the expense of tomorrow and flexibility. Companies requiring flexibility in the short term will tend to take a ‘capacity’ approach, involving the ability to scale to support short-term growth. Companies focusing on long-term delivery tend to take a ’standards’ approach, and require a high level of architectural and standards compliance, ensuring infrastructural ’spaghetti’ does not develop. Those companies focusing on long-term flexibility take an ‘options’ approach – experimenting with technologies and new skills to discover how useful these might be if the need were to arise. Their attitude to infrastructure is influenced greatly by the real options thinking described in Chapter 8.

Figure 9.4 Infrastructure approaches (source: Sauer and Willcocks, 2001)

As so much of the benefit of e-business is to be gained from integration and so much of the pressure arises from the rate of business and organizational change, Sauer suggests an alternative matrix for deciding which approach to take to manage the infrastructure and technology platform6.

In Figure 9.4 Sauer points out that a ’standards’ approach offers cost efficiencies through, for example, common deployment of technologies, potential for coordinated purchasing, reduced technology learning costs and less dependence on infrastructure-specific technical knowledge. However, standards are typically constraining, and the approach may well be more suitable where business change is slower and where the most that is demanded from infrastructure is efficiency. However, as Figure 9.4 shows, standards can also facilitate integration by providing common technologies and connections, although this may come with in-built inflexibility in the face of any rapid business or technology change.

Where change is rapid and integration less important, then a ‘deals’ approach becomes more appropriate. Resulting complexity in the infrastructure carries cost, but if integration is not required, then the deals approach is unlikely to impede delivery of business benefits. Where change is rapid and integration important, the demands on infrastructure are greatest. The ‘options’ approach is required to prepare the company for rapid changes involving internal and external integration. This must be underpinned by an integrated infrastructure that permits the rapid deployment of technologies identified by the ‘options’ approach, integrated with either/ both the company's internal enterprise systems and those of its business partners.

Some sense of the new evaluation challenges presented by moves to e-business and the need to move more towards an ‘options’ approach can be gleaned from Liam Edward's comments as head of the Infrastructure Team at Macquarie Bank:

Infrastructure development here (in 2001) is about, as each of the businesses jump, looking at how you make infrastructure flexible enough so that you can upgrade parts of it very quickly, because those parts impact on other parts of the infrastructure . . . it has been all about learning on the job within the context of a blueprint, as you gradually go out and implement it and take it forwards, putting in the bits that are required to take you to the next stage, and then learn again. Each time you break it into small enough chunks that are sustainable within the company, from both a cost and a service perspective. You then get the buy-in, move it towards the end-gain, and make sure you have an infrastructure that allows you to scale it, as the business growth occurs.

9.3 European Foundation for Quality Management

The EFQM began in 1988 with a group of 14 organizations banded together with the goal of making European business more competitive by applying a Total Quality Management (TQM) philosophy. The EFQM followed in the footsteps of major Japanese and US competitiveness awards. The EFQM embodies a number of objectives, including:

– the creation of an applicable EFQM model;

– an award program for successful users of the EFQM model;

– practical services to foundation members;

– educational services for foundation members;

– developing relationships among European organizations; and

– financial assistance for quality model applications.

The EFQM model is based on the concept of TQM. The more generic TQM philosophy embraces the determination of product and service performance requirements based on customer needs and the ensuing satisfaction of those needs with limited ‘defects’. In other words, TQM is the assessment of customer requirements and the delivery of quality in relation to those requirements.

Consequently, the concepts fundamental to the EFQM model are:

– a non-prescriptive framework;

– a customer focus;

– a supplier partnership;

– people development and involvement;

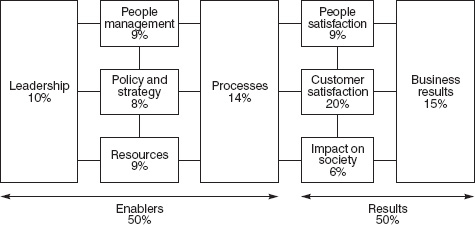

Figure 9.5 IT and quality: the EFQM model

– processes and facts;

– continuous improvement and innovation;

– leadership and consistency of purpose;

– public responsibility; and

– results orientation.

The EFQM model is a self-assessment evaluation mechanism based on nine criteria, each of which fall into one of two categories, the enablers and the results. Figure 9.5 represents the EFQM model, explained by these definitions:

– leadership: the behaviour of all managers in championing business excellence principles;

– people management: releasing the full potential of staff to improve what they do;

– policy and strategy: how the plans are formulated, deployed and reviewed and all activities aligned;

– resources: how assets and resources are managed for effectiveness and efficiency;

– processes: how processes are systematically improved to meet customer requirements and to eliminate non-value activities;

– people satisfaction: what is being achieved in terms of developing trained and motivated staff;

– customer satisfaction: what is being achieved in terms of satisfying external customers;

– impact on society: what is being achieved in terms of satisfying the needs of the community at large and regulators; and

– business results: what is being achieved in terms of planned financial and non-financial performance.

In practical terms, the model is used to identify what the organization has achieved and is achieving, in terms of performance and target setting. Results are reviewed over (ideally) a period of at least three years and are looked at in terms of competitor performance and best in class.

The self-assessment approach is defined as a comprehensive, systematic and regular review of an organization's activities and results referenced against the EFQM model for business excellence. The assessment can take place in any number of ways: a workshop, a questionnaire, a peer involvement approach or combinations thereof. Technically there is no one correct way to perform such a self assessment.

In order to examine the process in more detail, however, consider a questionnaire approach. A questionnaire could be developed based on issues relevant to the organization or based on templates that might be available from the EFQM. The questionnaire would then be administered to a group of individuals with each question requiring a ‘grade’ based on an agreed framework. For example, questionnaire responses could take the form of A, B, C and D grades, where ‘A’ represents ‘fully achieved’ and ‘D’ represents ‘not started’. After the questionnaire is administered, consolidated grades can be determined then discussed to reach consensus on the assessment output: an agreed list of strengths, areas for improvement and a scoring profile used for prioritization and subsequent execution of improvement plans.

Potential benefits of self assessment guided by the EFQM include:

– a revitalized and consistent direction for the organization;

– organizational improvement;

– a structured approach to business improvement;

– assistance with business planning;

– a manner of consolidating existing initiatives;

– a way to identify and share ‘best practices’ with the organization; and/or

– the provision of a common language for business excellence and improvement.

Several organizations have adopted the EFQM model in order to assess quality generically throughout the business, including in the IT function. As such, they have moved to an integrated way of measuring organizational and IT performance. Royal & SunAlliance adopted an EFQM framework as part of their merged evaluation techniques (see below). At the same time, there can be some downsides to the notion of benchmarking against best practice. Such concerns were voiced to us by the IT Managing Director at Unipart:

Unipart's commitment to provide its customers with constant product and service innovation, and continuous improvements to its processes is at the heart of its success. Therefore, the philosophy of following the lead of best practices (EFQM) players could, in fact, stifle Unipart's cultural and competitive success.

9.4 IT benchmarking

Consider the following case studies.

– A senior IT manager of Hewlett Packard summarized the organization's use of benchmarking:

There's a great deal of internal benchmarking. To give an example inside of Test and Measurement, our services are relatively well defined, and clearly priced, and we look very closely at the different cost structures and performance of our different organizations and business throughout the whole company. This allows for easier analysis and learning across the various service departments since we all use comparable data.

Ultimately, TMO (test and measurement organization) uses comparative benchmarking as a learning tool and to assist with management decision making.

– In 1993, BP Exploration outsourced most of its computer operations to a combination of IT suppliers. In order to get some idea of vendor performance, BPX contractually requested that the vendors benchmark themselves; this approach was initially less than successful. A senior financial manager explained: ‘We asked our out-source partners to benchmark themselves, so that became part of the service level agreement. On the whole they failed to provide quality measures for comparable purposes and we expressed displeasure in that area because it is a contractual item.’ Moreover:

It's a competition type thing, I don't think they wanted to give anything away or share. Plus I don't think they wanted to apply the resources to it. I think they would have liked to see the results, they were not frightened that they were not performing as well as another group. We were asking them to benchmark themselves against others who provided similar services to other parts of BP or to other companies because we wanted to see that they still were one of the best in class. But as I say that's getting nowhere fast.

Although benchmarking has been discussed in Chapter 4 in terms of development and operations evaluation, benchmarking deserves additional discussion because it is widely used by organizations. As illustrated by the cases, benchmarking addresses two challenges faced by IT managers:

(1) delivering cost-effective IT products and services – a rational challenge; and

(2) convincing senior executives that the IT function is cost effective – a political challenge.

According to Lacity and Hirschheim, benchmarking has been directed increasingly toward satisfying these challenges7:

’From a rational perspective, IT managers can use benchmarks to identify improvements to performance. From a political perspective, IT managers can present benchmarks to senior management as objective evidence that IT is cost effective.’

In addressing these challenges, an organization can view benchmarking as useful for one of the two following purposes.

(1) As a report card, which is politically motivated. This could create a very defensive environment, although many people still think this is a valid benchmarking reason.

(2) For improvement. However, while benchmarking may be appropriate in a number of types of application, there is much debate about whether or not benchmarking is most usefully used for identifying and replicating best practices.

Effective benchmark approaches

IT managers and organizations benchmark in four main ways.

(1) Informal peer comparisons. IT managers trust the informal gathering of peer data even if the peers are competitors. However, the problem is that IT performance evidence gathered in such a manner often fails to convince senior business management.

(2) Informal outsourcing queries. Outsourcing research indicates that, on an increasing basis, IT managers attempt to get informal ‘benchmarking’ assessments through potential outsourcing vendors and the bidding process. However, vendors have caught onto the trend and, as a result, no longer take such enquiries seriously. One way forward is for the vendor to charge for a detailed assessment of how its own performance might compare against the in-house IT team.

(3) Formal outsourcing evaluations. Such evaluations were dealt with in Chapter 6. An evaluation of this nature can represent one of the most definitive benchmarks available, but can be expensive and disruptive, not just to the company, but also to the vendor, especially if the vendor's bid is turned down in favour of another.

(4) Benchmarking services. Formal benchmarking services can provide access to a wealth of data, can be presented to senior management as ‘objective’, and may overcome political obstacles to internally generated benchmarking. However, customers often fail to clearly articulate their benchmarking needs to the benchmarking service. IT managers also express concern over who they are actually being benchmarked against in the IT benchmarking services’ databases. Furthermore, while many are comfortable with what are termed ‘mature’ areas for benchmarking (e.g. datacentre operations and customer satisfaction), they may be less sure about applications development and support, cost of ownership benchmarking and benchmarks for the areas of telecommunications and network management. In particular, many organizations are not clear how external benchmarking services could help in the benchmarking of the business value contribution of such operations.

Quality of benchmarks

Based on their research with senior executives and related benchmarking experience, Lacity and Hirschheim identified a number of concerns about the quality of benchmarks. These can be summarized as:

(1) benchmarks are too technical – they don't translate well to user terms, such as customer satisfaction or profitability;

(2) benchmarks do not indicate whether IT has adopted the right architecture – the IT organization can reduce costs endlessly but that reduction does not intimate appropriate results for an organization;

(3) benchmarks sometimes focus on the wrong IT values – for instance, if the organization is focused on service excellence, but benchmarks are focused on cost containment, the means and ends are mismatched;

(4) benchmarks may not be viewed as valid – unless attention is paid to reference group selection, the normalization process, measurement period, data integrity and report design quality.

Benchmarking guidelines

The following guidelines for pursuing effective benchmarking activities arise from the following concerns raised.

– Benchmark what is important to senior management – there is a need to take into account business managers not just IT managers. Are they interested, for example, in cost efficiency or service excellence?

– Ensure that benchmarks are not too technical for senior management. They are not interested in or persuaded by narrow technical benchmarks. They want to monitor items that have salience in business terms.

– Senior management should select the benchmarking service. This avoids suspicion falling on the IT function of selecting a service favourable to it.

– The benchmarking service should select competition that reflects senior management's concerns, for example size, industry and geographic span.

– The perceived objective role of the benchmarking service is crucial. So, for example, its employees should gather the data themselves, hold a validation meeting prior to data analysis and design meaningful reports.

– The benchmarking service should select the reference group which represents the stiffest competition possible. As one data centre manager commented, ‘you need to benchmark against the toughest in town’.

– Gather data during a peak period. Avoid a-typical data and data applicable only on a limited basis.

– Keep repeating the benchmarking exercise and regularly update benchmarks.

– Benchmarking must identify concrete, feasible improvements.

9.5 Cost of ownership

The cost of ownership is a means of describing not only the direct, visible costs of technology, but also the indirect, hidden or knock-on costs associated with various types of technology investments – the sort we met in Chapter 1. Specifically, the concept of cost of ownership deals with the idea that, in order to use and support technology through its lifecycle, significant costs are incurred. For instance, the purchase of a desktop system by an organization is not the end of the costs associated with that computer. Instead hardware, software, training costs, network connectivity, support and maintenance, peripherals, end user operations, downtime and upgrade activities all add to the total cost of ownership of that computer. For instance, hardware and software costs account for only 20–25% of the costs of ownership. Gartner suggested in the late 1990s that cost of ownership for maintaining the average PC was about US$9,000 to US$11,000 per year. Compass said it was closer to US$3,000. Mobile users regularly underestimate the cost to own. For example, Gartner has suggested that laptops have been 50% more expensive (in terms of cost of ownership) than desktops and only last 30 months.

Recurring mention in the press of cost of ownership has made both organizations and individuals more aware of these additional costs. It follows that, in order to manage these costs successfully, a measurement regime is required to quantify and establish goals for containing costs. The desktop networks, so insiduous in organizations today, are perhaps the best example of IT investments with related costs of ownership. Given this prevalence, it would make sense that the desktop PC would be the best managed part of IT infrastructure. The reality, however, is that costs are excessive, reliability is poor and compatibility is uncertain. Managed costs and increased integrity depend on increasing the coherence of the infrastructure, based on standards for hardware, software and networks.

According to one experienced practitioner:

Our goal should not be to minimize costs and downtime, but to maximize the value of IT to the business . . . to increase IT's value we should increase our understanding of business needs and apply that understanding creatively . . . IT managers should look for ways of increasing the value obtained from existing technology, rather than chasing new technology. And we should encourage line managers to take responsibility for the use of technology in their departments. Desktop systems are a vital part of every organization's systems infrastructure; increasingly they are the infrastructure. Therefore, the future of business will depend more and more on these systems. The future of IT lies in ensuring that they make the maximum contribution to business success.

The cost of ownership can be effectively managed in a number of ways. One way, although certainly not the only or best one, is the possibility of outsourcing the management of technology investments with significant costs of this sort. As demonstrated in Chapter 6, outsourcing should utilize or introduce effective measurement schemes into the process so that an organization can comprehend the size and scope of what it is outsourcing. Expected benefits from outsourcing are clear: improved service, enforced standardization and commercial awareness in users, more resources and stabilized costs. On the flip side, however, users need to understand that suppliers are still going through a learning curve on the desktop and frequently have not yet reached the level of stable, commodity pricing available with mainframe services.

A perennial problem in cost of ownership calculations for the desktop environment is the wide difference in figures arrived at by different benchmarking companies for ‘cost per PC seat’. To an extent, this reflects different cost of ownership models, lack of standardization across benchmark services and sometimes immaturity in the benchmark service being offered. What is important is that the model selected offers a structure for understanding what creates the cost of PC ownership. One such model is suggested by Strassmann8. Costs are determined by customer characteristics, technology characteristics and application characteristics. In turn, these determine the costs and nature of workload volumes and network management practices. Together workload and network management practices produce the total cost of ownership. Not surprisingly, given the variability in these factors likely from site to site, cost of ownership figures do vary greatly across organizations. Identifying the cost drivers of PC costs in detail and managing these down, creating a consistent technology architecture and insisting on adherence to standards are three of the ways forward for reducing or managing the cost of ownership.

In summary, costs of ownership considerations are additional drivers for the need to measure and manage IT investments. Companies such as Gartner and Compass have developed models to help manage these processes. Gartner Group's updated total cost of ownership model includes direct costs (hardware, software, operations and administrative support), indirect costs (end user operations and downtime), maturity of best practices and complexity in its total cost of ownership calculation. Among other results, this form of evaluation helps organizations evaluate more sophisticated technologies and labour-intensive processes such as peer support.

To manage the cost of ownership more effectively:

(1) don't prioritize line-of-code costs, instead make ease-of-use a top concern when writing in-house code;

(2) remember that hardware and software costs are only a portion of total costs – user satisfaction, technological complexity and best practices maturity also contribute;

(3) if using consultants to advise on cost of ownership, never let them recommend a single solution, instead insist on being given several options;

(4) consider training costs carefully – often staff get only one day a year of technology training and it is poorly targeted; and

(5) ensure your costs of ownership are not being dominated by the ‘futz’ factor – the time staff use their desktops for personal matters.

9.6 Corporate mergers and acquisitions

Despite the rapidly paced business environment and the related trends in mergers and acquisitions, there is not much literature available on the relationship between mergers/acquisitions and IT usage and/or rationalization. The Royal & SunAlliance case at the end of this chapter provides an example of the effect of a merger situation and the subsequent successful rationalization of information technology usage. In general, however, the scant literature available reports a bleak picture on the successful combination of merged/acquired technology. Jane Linder investigated mergers and acquisitions in the banking industry to discover the effects upon IT applications. Her findings reflect disparity between what managers would describe as the ideal integration among applications in both merger and acquisition arenas and the realities which ensued9.

Linder conducted a series of interviews in the banking industry to determine the ‘ideal’ circumstances and results for systems integration in both mergers and acquisitions. Bankers described the ideal integration effort in an acquisition as one that would be implementation-intensive rather than design-intensive, with the smaller partner adjusting its practices to the larger ‘parent’ organization. Ideally, the acquiring bank's applications would be technically and functionally superior to the acquired partner's. Only unique and innovative applications from the acquired bank would be adopted for the entire enterprise. In mergers, on the other hand, managers described a more collaborative approach as the ideal systems integration process. The equal partners would develop a plan that reflected a resulting operation incorporating the best of both parties.

As mentioned above, the actual results of the systems integration efforts in the mergers and acquisitions monitored by Linder were far less effective than the ideals and usually resulted in:

– slow flow of IT integration savings to the bottom line;

– loss of competitive momentum; and

– adoption of systems not necessarily technologically or functionally superior.

Linder identified that mergers and acquisitions, and consequently their related systems integration efforts, are highly political in nature and are rarely managed effectively. She identifies the critical integration factors as:

– the balance of power between the organizations merging/ acquiring;

– a difference in beliefs and cultural values of the involved organizations; and

– deadlines imposed by the merger/acquisition.

Royal & SunAlliance provide an example of a merger situation in which application rationalization worked more effectively than perhaps the picture has been painted by Linder. The Royal & SunAlliance case study provides an effective illustration of the interaction between technology evaluation and a number of the special issues covered in this chapter including corporate mergers, infrastructure rationalization and the EFQM. The case study will describe the business and technology contexts of the merged organization and then examine each of the issues in more detail.

9.7 In-depth case study: Royal & SunAlliance Life and Pensions (1996–2001)

Business context

The SunAlliance Group merged with the Royal Insurance Holdings plc in July 1996 to become the Royal & SunAlliance Insurance Group. The combined organization reported a combined profit of £809 million in 1997 from insurance transactions and related financial services. 1997 represented a year of integration for all of Royal & SunAlliance's (hereafter referred to as RSA) business units, IT included. This merger provided the dominant characteristic of the business environment within which a number of other ’special’ issues came to light.

IT context

While the merger of SunAlliance and Royal Insurance obviously provided the most immediate influence over the direction of the combined IT department, RSA Life IT could not afford to ignore a number of other significant issues on the horizon, including infrastructure issues, continuing service delivery and Y2K. Mike Parker, RSA Life IT Manager provides an insightful description of the issues confronted by the IT department going into 1997:

You can imagine now we have systems that are being used in locations that they were never designed to be, and being used by people new to these systems. This means that we have connected systems together through infrastructure that was never designed to be used in this way. Therefore, we have a real challenge to maintain and upgrade the infrastructure, the LAN networks particularly, as work has been moved around the country. We've closed some regional offices localizing the servicing in Bristol, Liverpool and Horsham. You can imagine the facilities that have had to be upgraded, etc. So we struggled last year to consistently meet our production service targets. Now it is much more stable.

The combined IT department employed 320 persons in 1998 and maintained three centres with nearly 100 separate applications, of which 30% were designated as ‘critical’. The computing service was provided by an IBM-owned datacentre in Horsham, and an in-house datacentre in Liverpool. The IT staff was split 70/30 on development and support activities. Both pre-merger organizations were very traditional about measurement and measuring computing availability; the merger forced the combined organization to consolidate and rationalize systems, thus placing real focus on end-to-end service measurement.

The merger: four issues

The merger alone presented a number of issues requiring examination with respect to the impact on the organization and the organizational response. In part, the impact and response had a direct effect on the subsequent technology evaluation processes undertaken.

(1) Two of everything

As separate organizations, Royal Insurance and SunAlliance had used nearly 100 business applications and in excess of 20 supporting technologies to support their businesses. The merger forced an assessment of applications in light of their ‘criticality’ to the business and in light of the potential duplication of services that now existed. In addition, because of the size of the combined RSA and the historical depth of available policies, a migration to a consolidated platform was necessary. Mike Parker explained the situation:

We've gained two of everything at least. We've inherited more technology platforms and more applications than we are ever likely to need in the future, and, of course, where the support is provided from depends on which application is chosen. Therefore, in an integrated systems architecture, you are also faced with having to interface elements of an outsourced computing service to an insource service.

It is interesting to note, in light of the plethora of systems, that RSA did not consider IT to be on the critical path to product delivery. Instead, RSA chose to look at IT as an ‘enabler’, which could enhance the product-delivery process. It is perhaps because of this perspective and attitude that the merger presented an opportunity for rationalization rather than a roadblock to continued ‘good business’. Client servicing and product availability were seen as dual business drivers.

The organizational response to the duplication of applications and technology was ultimately the rationalization of those systems using a detailed workflow map developed as a guideline. Parker explained:

. . . both companies had their own strategies to do this kind of integration – they were different but complementary. In fact we had the solution in one company to some of the problems that we had in the other company. For example, we didn't have strategies in SunAlliance for a couple of systems, and Royal had a solution that could (and did) resolve SunAlliance issues.

The result was a strategic systems plan that provided the blueprint for the integration that spanned most of 1997.

(2) Instability

Despite the seemingly successful approach to application integration and rationalization, the complexity of the merging of IT infrastructures introduced a level of instability into the ongoing delivery of IT services. Parker described the situation:

What we did not have initially was a stable environment. Software merger equals instability. Previously, there was not the same requirement from either organization to change what wasn't broken. But immediately you actually have to change systems that you'd rather not touch, you start getting instability . . . Overnight things fall over because of transaction volumes processed through the systems being twice as big as they were before, and many weren't designed for that volume (transaction load).

Again, the organizational response to this dimension boiled down to the concept of assessment and evaluation. Parker described the resulting focus of the organization:

So if you like, it was the challenge of instability that has caused us to actually understand what's important to the business and put in place some of these measures. I think our focus has increased tremendously.

(3) Outsourcing

Events at RSA bring another spin to the outsourcing debate, namely the additional set of complications introduced by a merger process. These generate the need for additional assessment of existing outsourcing contracts. Prior to the merger, SunAlliance outsourced its datacentre to IBM. Royal Insurance, on the other hand, was all in-house. Since the merger, what was once the Royal General business, residing on the Northampton datacentre, moved to the out-sourced contract. By 1999, all that remained of in-house computer operations was the ex-Royal UK Life datacentre in Liverpool. The IT Life plan, mentioned above, provided some level of guidance in terms of identifying strategic development. RSA Life determined, post-merger, not to outsource strategic application development.

(4) Staff retention

The process of the RSA merger created stress on IT staff in two ways: the uncertainty regarding the role to be played going forward and an uncertainty about a go-forward work/living location.

In response to the staff retention issue, Life IT management were determined to make site a ‘non-issue’. Consequently, the strategy was to actually challenge everyone to make site a nonissue as far as IT was concerned, regardless of the fact that a lot of the business departments that were previously ‘local’ had now moved. Whereas all the head office functions and head office systems were originally at Horsham, post-merger head office systems were split between Horsham and Liverpool. In addition, Liverpool moved part of its client servicing to Bristol. Consequently, the majority of systems teams are servicing users not on the same site. The challenge has become to understand what is needed to develop and support systems remote from the user base. This strategy has been very successful.

In addition, RSA Life introduced some measures of selfassessment in the form of the EFQM (see below). Part of that assessment included the consideration of ‘people management’ as an enabler within the organization.

IT infrastructure: emerging challenges

The combining of RSA Life's IT infrastructure exposed the merged organization to a level of risk. The IT Life plan included a number of infrastructure decisions made as a result of the merger and brought additional focus to bear on future infrastructure issues.

Prior to the merger, both organizations were very traditional in terms of equating CPU availability with the conduct of business, because of a lack of complexity in the infrastructure. After the merger, however, with users dispersed in many different locations, mere CPU availability no longer told the whole story of the users and their ability to conduct business. For instance, often, an application would be running on the mainframe, but a user could not access it. Or an application would be running fine for two locations, but not for a third.

As discussed in this chapter, infrastructure is an issue in and of itself because of the difficulties associated with:

(1) justifying an initial infrastructure investment; and

(2) evaluating the ‘performance’ of the infrastructure, as benefits reaped are usually the result of uses and applications built on top of the infrastructure rather than deriving from the infrastructure itself.

As a result of the merger, RSA Life renewed its interest in rationalizing and evaluating infrastructure investments. The IT department selected a sponsor for infrastructure investments and identified new and more effective means for building the infrastructure business case. Mike Parker was designated as the sponsor for infrastructure investments and commented on the improved business case approach:

We articulate what would happen if we did not make the investment – in other words, compared with continuing the way we are, quantify the effect on service levels and cost. We've developed some algorithms in conjunction with the client servicing manager and servicing functions to quantify the cost of both downtime and deteriorating response times on the business. So we are building a model of how many people are affected if we lose an hour's worth of processing. Then you can use the model to extrapolate some of your own business infrastructure investments.

The IT Life plan outlined the large infrastructure and platform rationalizations that were in the pipeline; the delivery of the particular aspect of the plan was geared towards Y2K compliance.

The millenium problem

The Y2K compliance issue hosted a number of problems covered above, but the RSA merger could have been considered a potential risk to the organization's ability to attain compliance. Instead, RSA viewed Y2K as a ‘godsend’ because it provided the management focus which cleared away all the ‘nice-to-haves’ and hurdles in the way of implementing key aspects of the strategy.

RSA's response to the issues raised by the Y2K focused on the on-going evaluation of resource allocation and compliance. As mentioned above, IT staff felt a degree of strain in relation to the merger. The Y2K project(s) only served to reinforce that strain. To address the staff concern, RSA chose to outsource a part of the Y2K effort and used Y2K compliance to reinforce the migration of a large number of the applications deemed noncritical.

On-going assessment and evaluation of the compliance effort was considered a critical effort. For such critical undertakings, milestones are documented, then each month milestones achieved are checked against milestones planned.

This planning and control process also helped the IT department to address the cross-purpose needs of the business. Some divisions of RSA attempted to bundle non-compliance issues/ requests with compliance fixes. Parker explained:

We now have put in place what some might call excess bureaucracy to stop people requesting changes on existing systems. This is in order to ensure that this resource is kept to a minimum. In other words, we only fix it if it fails and we only do things that are essential. Of course, the businessmen could be smart enough to think all they need to do is bundle up their ten requirements inside one legislative requirement and it will get passed as essential. So we have now said sorry we are unbundling everything.

Adopting new measurement models

The EFQM

RSA has experimented with a number of assessment methods, including one on business excellence based on the EFQM model (discussed above). RSA initially used the EFQM, as per Figure 9.5, as a means of self assessment. Although business excellence assessment comprised more parts of the organization than just the IT department, its use in the IT department contributed to the overall evaluation of less tangible benefits. This self-assessment process was conducted within IT by the staff:

It measures how good we are at all aspects of management. I like that. I've seen a few models in my time now. This one I feel comfortable with in that it measures how good you are at all elements, which are called enablers, and how good the result is. So you should see if you do a lot of improvement work how it does bring results. It is capable of being compared across industry and cross-function within industry as well. There is an absolute score out of the assessment, and you can put yourself into a league table if you so wish.

Monthly reporting models

Post-merger, the RSA IT department also developed a project monthly report process. The process included a number of key performance indicators documented with ‘red-amber-green’ (RAG) charts. In addition, program boards monitored the key milestones.

In 2001, reporting monthly is continuing up through the IT organization, right from the staff time recording. The project monthly reports capture the effort, the tasks and the key milestones planned and actioned during the period. As it comes up through the organization these are turned into various management graphs of how well IT is doing against its key performance indicators. The RAG chart shows IT its ‘health’. The critical projects are also listed. Each project is followed by a trend chart of what has happened over the previous few weeks and months. Production support – in other words, the capability to support RSA production systems – is also monitored, because there are some critical systems there which are also old and less robust. Key performance indicators are also reported, including budget, staff headcount, contractors, movements of staff, attrition rate and absenteeism. Therefore, those things that affect IT's capability to deliver are being controlled independently. The report goes up through the directors to the managing director on a monthly basis.

E-business and future directions: going global

For a conservative industry, it has been necessary to take change in increments. ‘Each step is transformational’, explained Phil Smith, RSA's Global IT Director. As a result, RSA has taken a softly, softly approach to e-business. Rather than disrupting existing business relationships with intermediaries, it has opted to develop the global infrastructure. Where conventional wisdom insists that the insurance business is different everywhere and, therefore, requires different processes and systems, Smith argues that they are 80% the same worldwide, with 10% regulatory variation and 10% miscellaneous variation. One opportunity being pursued throughout 2000 was the introduction of global communications to underpin global knowledge management within the group.

The idea was to identify, articulate and share current best practices in product development so as to implement them uniformly across the globe and then develop them for the future. Without a budget to underwrite the full global network, country budget-holder support has been crucial. The result of this drive has been that over three years RSA has moved from having a federated platform with few connections to having a global communications network supporting knowledge management processes through Lotus Notes. Smith explains:

Because we have pieces of wet string between some places and no pieces of wet string between others, Lotus Notes is very suitable for e-mail and intranet because it has a replication capability that can be run over dial-up links such as ISDN . . . it's now pretty much complete throughout the world and we now understand the extent to which a person on a desktop in Thailand can talk to a person on a desktop in Chile.

In addition, a common set of binding technologies has been promoted consisting of e-mail, an intranet, MS Office, Adobe and Internet Explorer. These are technologies that would allow a company to function globally whatever its business. From dismissive comments such as ‘Why do we need this?’ the responses have changed to ‘When can we have more?’.

Planning, evaluation and funding

At present, RSA has set out on its journey but has many more ports of call to visit before the vision is realized. What has it taken to get this far? What change will it take to make further progress?

Planning cycles have been one issue. RSA IT managers are aware from the immediacy of the demands of e-business initiatives that planning has to be reviewed constantly. Linked to this are the issues around evaluation and funding. While some see the need to adjust processes even if it involves taking some losses on investments, others argue that traditional measures such as return on investment have served the company well and should not be abandoned. Phil Smith has adopted a middle way of introducing some new processes, including hot-house incubator environments while retaining some traditional measures. RSA has found infrastructure difficult to justify against the traditional measures. Nobody knows what the savings on their worldwide communications network will be. Even suppliers such as British Telecom have been unable to provide data for similar investments by other companies, so argument by analogy is precluded.

In conclusion, how can you achieve effective global decisionmaking in a federal organization? The trick, Smith contends, is ‘to set up good consultative processes – then sometimes within this you have to be autocratic. Our worldwide e-architecture is going to have to be standard, with buy-in worldwide’.

Case learning points

– A merger combined with Y2K on the horizon provided an opportunity to rationalize technology usage by the combined organization. Rather than becoming the cause of disorientation and distress, the merger was the opportunity for a high level of rationale systems planning and a vision for the combined use of IT.

– A merger should not be thought of as the silver bullet that will clean up decentralized and unorganized technology usage, although in this case RSA chose to view the organizational upheaval as an opportunity for positive change. It is perhaps this positive perspective on the change that allowed RSA Life to succeed under the circumstances, illustrating the significance of psychology in IT evaluation and decisionmaking.

– However, there are few occasions when an organization will undertake sustained improvement in IT evaluation practices. Clearly, a merger or acquisition requires clarity, change and new ways of working and can act as a catalyst in the IT arena. In such a scenario, evaluation plays a fundamental role and new IT measurement approaches are both likely and sustainable.

– A principal learning point is the difficulty of driving e-business change in a conservative industry from Group IT. The importance of leadership, both business and technological, from the CIO is abundantly clear. When the organization itself is inflexible, it is necessary to step outside the normal boundaries.

– Driving infrastructural change globally is also a challenge in a highly decentralized business which sees itself as differentiated across country boundaries. Evaluation techniques can help the case for infrastructure investment, but there will still be significant political issues to deal with. Group IT needs to be as flexible as possible. The new role of the CIO is to be a global business person with strong IT skills, not just a diehard technology expert. The new CIO role is critical to this model.

9.8 Key learning points

– Since 1996, a number of critical issues have emerged that have caused organizations to revisit and extend evaluation practices. These include the Y2K, EMU challenges, the possibility of utilizing the EFQM model for quality management in IT, IT infrastructure, benchmarking cost of ownership and e-business issues, and the implication of rapid change, in particular mergers/acquisitions, for IT evaluation.

– The Y2K problem was viewed as either a serious difficulty or as an opportunity to review and rationalize large parts of an organization's applications. A minority of organizations took the latter view with the considerable benefits that resulted from it.

– The EFQM model for evaluation is being utilized by several of the organizations researched with benenficial results. At the same time, there can be some downsides to the notion of benchmarking quality against ‘best practice’ (see Chapter 8).

– IT infrastructure evaluation has emerged as a critical issue in a period of cross-over between technology eras (see Chapter 7). In the base case, infrastructure investments must be dictated by business strategy. From business maxims can be derived IT maxims that inform IT/e-business infrastructure development.

– Benchmarking is a necessary but insufficient evaluation practice for the contemporary organization. It is used both to assist delivery of cost-effective IT products and to convince senior executives that the IT function is cost effective. Both purposes are fundamental – neither can be neglected in the design and operation of the IT benchmarking process.

– Cost of ownership is confused by widely published diverging estimates. Cost of ownership depends on customer, technology and application characteristics which influence work volumes and network management practices. Identifying the PC cost drivers in detail, managing these down, insisting on adherence to standards and creating a consistent technology architecture are three ways forward for reducing costs of ownership.

– Organizational changes, such as mergers and acquisitions, require intense IT rationalization. Previous research paints a bleak picture, but our own research has found examples of effective IT evaluation and management practices being applied.

9.9 Practical action guidelines

– Required, large-scale changes to your technology investments, for example EMU and Y2K, should be considered an opportunity to rationalize IT spend.

– Balance the cost-reducing opportunities with the productdevelopment opportunities in the investment in technology.

– As always, plan the entire lifecycle of the IT investment and evaluate on an on-going basis.

– Remember that no organization can go from ‘no best practices’ to ‘all best practices’ overnight. A phased approach is required. For instance, in the adoption of the EFQM, an organization should focus first on those components that are required for the basis of on-going EFQM evaluations that are currently lacking or undermanaged in the organization. Likewise, benchmarking figures are relative and are not necessarily appropriate targets for every organization.

– IT infrastructure investments must be dictated and aligned with business strategy.

– In managing your cost of ownership, take into account not only the obvious ‘direct’ costs, but also the indirect costs such as user satisfaction, organizational complexity and the maturity of best practices.