The Construction of Incompetence During Group Therapy With Traumatically Brain Injured Adults

University of Rhode Island

Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan

Wayne State University

INTRODUCTION

Language and language incompetence do not exist as independent phenomena in the heads of speakers; they present themselves in contexts of interaction. From an interaction vantage point, internal language capacities do not predict communicative proficiency:

In order for two or more people to communicate, at whatever level of effectiveness, it is neither sufficient nor necessary that they “share” the same grammar. What they must share, to a variable degree, is the ability to orient themselves verbally, perceptually, and physically to each other and to their social world. (Hanks, 1996, p. 229)

Speakers with severely impaired language abilities are able to communicate quite effectively, given the right interactional circumstances. Goodwin (1995), for example, described how a man with aphasia, who produced only three words (“yes,” “no,” and “and”), was able to effect conversational meaning through the interactional work done by all participants: “Moreover, Rob’s severe deficits in the production of words are not accompanied by equal restrictions on his ability to recognize, and actively participate in, the pragmatic organization of talk-in-interaction” (p. 252).

The idea that language and language incompetence are situated interactionally is not a trivial one, particularly for professionals working with those suffering from brain injury. As Goodwin (1995) notes, failure to appreciate this point can have disastrous consequences:

When Rob was in the hospital, his doctors, who had focused entirely on the trauma within his brain, said that any therapy would be merely cosmetic and a waste of time, because the underlying brain injury could not be remedied. Nothing could have been further from the truth, and medical advice based on such a view of the problem can cause irreparable harm to patients such as Rob and their families. As an injury, aphasia does reside within the skull. However, as a form of life, a way of being and acting in the world in concert with others, its proper locus is an endogenous, distributed, multiparty system. (p. 255)

Speech-language therapy is one of the contexts in which the language abilities and disabilities of those suffering from a brain injury come to interactional life. A primary goal of therapy from the speech-language pathologist’s (SLP’s) perspective is to improve the communicative competencies of individuals deemed to be impaired. Yet studies focusing on therapy as an interactional practice are in their infancy. For the most part, these investigations have analyzed dyadic, individualized therapy sessions involving an SLP and a child. Similar to other studies of professional discourse, particularly classrooms (Cazden, 1988; Mehan, 1985; Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975), these investigations reveal interactional asymmetries (Duchan, 1993; Kovarsky & Duchan, 1997; Panagos, 1996; Prutting et al., 1978). SLPs tend to regulate the distribution and evaluation of information, and control access to the interactional floor to achieve a set of prespecified goals and objectives (Kovarsky, 1990; Kovarsky & Duchan, 1997; McTear & King, 1991). This type of intervention has been dubbed “trainer-oriented” or “adult-controlled” (Fey, 1986).

In their strong form, “trainer-oriented approaches” consist of tightly scripted games and routines that are regulated by the SLP (Kovarsky & Duchan, 1997). Practitioners are oriented toward evaluating and repairing perceived errors in the client’s communicative performance (Damico & Damico, 1997). Such repairs often manifest themselves in three-part, evaluative sequences similar to those described in the literature on classroom discourse (Cazden, 1988; Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975). Here, the SLP makes a request for known information (a quiz question), the child responds, and the clinician evaluates the appropriateness of that response. If the answer is judged appropriate by the clinician, no repair work is undertaken. If the response is considered inappropriate, repair work is initiated until the child provides the desired response. In these repair trajectories, clinicians may provide a series of hints and clues over a number of turns until the child produces the correct reply (Kovarsky, 1989a). On receipt of the appropriate response, the clinician frequently offers an overt, evaluative comment such as “good talking,” “great job,” or “okay.” These evaluative markers may be accompanied by nonverbal gestures like smiling and vertical head nodding (Damico & Damico, 1997; Kovarsky, 1989b).

In other words, traditional therapy often revolves around correcting errors in performance of those who are perceived to have problems in communicating: “We will change anything and everything in an effort to get that ultimate plum of teaching—the correct response” (van Kleeck & Richardson, 1986, p. 25). Put another way, without errors to remediate, there would be no therapy. This error-maker expectancy pervades trainer-oriented approaches: Clients come to therapy because of perceived communicative incompetencies and participants construct therapy around remediating these mistakes (Kovarsky & Maxwell, 1992). Within this interactional framework, clinicians declare what communicative performances are to be judged as inadequate and when these errors are considered to be “fixed.”

While these studies do reveal global asymmetries, they do not fully address how participants negotiate meaning during therapy. This chapter goes beyond previous investigations in two ways. First, instead of focusing on dyads with children, data involving an SLP working with a group of adults with traumatic brain injuries are examined. Second, attention is focused on how participants work to construct meaning on a turn-by-turn basis rather than being focused on interactional asymmetries. This type of analysis provides a window for viewing how competence and incompetence are negotiated in group language therapy speech events.

COLLECTING AND ANALYZING THE DATA

Group language therapy sessions involving at least one SLP and adults with traumatic brain injury (TBI) were videotaped and transcribed. Video recording took place in a large rehabilitation hospital located within an urban complex of medical facilities. The rehabilitation unit housed a variety of allied health professionals, including occupational, physical, recreational, and speech-language therapists. While a total of 20 sessions were recorded over a 5-week period, this investigation focused on the first session because it was here that particular communicative practices emerged that were sustained across subsequent meetings. On any given day, the caseload of the SLP could vary depending on the number of admissions to the TBI unit and the nature of the injuries suffered by the patients. Over the course of the entire investigation, group size varied from two to six patients. In this session, the SLP conducted therapy with five adult participants.

Individuals had to meet the following criteria established by the rehabilitation unit before being allowed to take part in group therapy: (a) mild to moderate impairment of cognitive-communication skills; (b) the ability to sustain dyadic interactions in conversation; (c) the capacity to recall the content of structured interactions within therapy sessions; (d) the ability to orient to the purpose of the therapy group; (e) the facility to initiate social greetings; (f) the capacity to orient to person, place, and time during an interaction; and (g) the ability to utilize compensatory strategies for activities such as recalling information. Finally, all participants had to score 5, or better, on the Ranchos Los Amigos Scale. In other words, individuals had to reach a certain level of environmental and communicative awareness before being allowed to participate in group therapy.

Prior to videotaping and transcribing the group language therapy sessions, the SLP who conducted this session was interviewed. She was asked to discuss the nature of her workday at the rehabilitation hospital, her clinical background and interests, and the goals and objectives of intervention in this setting.

The three co-authors met on a regular basis to review the videotaped session and the accompanying orthographic transcription. Because the SLP who conducted the group therapy session had a full caseload, she did not have an opportunity to participate in these videotape review sessions. However, one of the co-authors (M. Kimbarow) who viewed the tapes was in charge of the rehabilitation unit, familiar with the SLP who conducted group therapy, and had over 20 years of professional experience as an SLP with adult populations.

DESCRIBING THE INTERACTIONS

Analysis revealed that therapy consisted of a series of gamelike activities where much of the interactional work done by the SLP was to ensure that patients followed the rules. There were times when this focus on the rules appeared to be at odds with the overall goals of intervention. Furthermore, when playing these games, memory was often treated as a static, decontextualized skill requiring individuals to generate and remember lists of items. Discussions between the SLP and the adult clients concerning how these generated lists might be constructed or remembered, with respect to personal human experiences, were frequently discouraged.

Together, these communicative practices served to reduce the level of competency displayed by the patients in therapy. That is, the data revealed a mismatch between the overall purpose of intervention—to facilitate the communicative competencies of individuals with TBI in everyday life—and the interactional patterning of therapy. Since intervention is a planned speech event, understanding the relationship between the agenda of the professional and the moment-to-moment unfolding of intervention is crucial. It is our contention that prevailing clinical practices and institutional constraints provide a ready resource for constructing incompetence among individuals with TBI during therapy.

The remainder of this discussion is organized as follows. First, the institutional constraints of the rehabilitation setting are considered. Next, the overall goals of intervention within the TBI unit are described, followed by a discussion of the SLP’s clinical agenda within this context. It is argued that the intervention activities described by the SLP are based on models that disembed language and cognition from everyday activities. It is against this backdrop that the competency-lowering practices of the session are presented on a turn-by-turn basis through transcribed examples. Finally, the implications of these findings are discussed.

INSTITUTIONAL CONSTRAINTS OF THE REHABILITATION SETTING: PLANNING AND SCHEDULING THERAPY

The population served by the rehabilitation hospital was quite varied. Patients ranged from 20 to 60 years of age and were members of a variety of cultural and ethnic groups. The traumatic brain injuries sustained by these individuals were most often the result of assaults and motor vehicle accidents. An effort was made to serve these individuals soon after their accidents to maximize treatment outcomes. Because people came to the unit on an emergency basis, therapists often had little advance notice as to who would be joining or leaving their caseloads from one day to the next. As the SLP stated, “there is no typical day” because of the heterogeneous nature of the injuries suffered by individuals with TBI, their consequences, and difficulties scheduling therapy:

… if someone’s agitated, you spend a lot of time convincing them to leave the room and come to therapy … if my nine o’clock is ready, I’ll start with that. If they’re not ready, I look around and see who’s free. And if they’re free, I grab ’em. And that’s also a good way to judge if they’re flexible. Because we’ve got patients, that on the schedule [if] it says ten-thirty, they will say “I will NOT come see you before ten-thirty.”

Given the unpredictability of scheduling and the nature of injuries suffered by individuals with TBI, planning therapy could be difficult. Beyond this, the SLP added that one of the most troublesome intervention issues was the lack of information about the personalities of individuals before their injuries:

… [individuals with TBI] have all these deficits but premorbid personality, I think, plays a huge role in how the person is after the injury. And that’s why I REALLY like to talk to the family. And with our population it’s often not possible ’cause there isn’t any family, or isn’t any family who cares to be involved. And it’s sad. It makes it tough because you have no baseline. You have no clue. This person’s weird [but] were they weird before? There is no normal person … so somebody seeing me after a head injury doesn’t know if maybe I didn’t say a word before. They don’t know.

Without background information, it was hard to intervene in a way that accounted for the individual lifeworlds of those receiving therapy. This, coupled with the lack of predictability in scheduling and the diversity of injuries, encouraged a situation where therapy games were selected and played by a set of rules that had little to do with personal human experience. In this way, there was a baseline for judging therapy performance without regard to the life histories and perspectives of those with TBI.

Finally, with respect to planning, there were issues in accountability and reimbursement from health care providers. With health care practices in the United States undergoing radical transition concerning how services will be funded, the therapists must have objective measures for demonstrating progress in order for the rehabilitation unit to receive funding. Influenced by positivistic models of science and progress, accountability translates into counting behaviors that can be measured reliably. Therapy activities that, for example, measure improved memory according to the number of listed words produced by individuals with TBI lend themselves to this kind of accountability. Perhaps what is most ironic is that although insurance companies are interested in accountability, they are also concerned with how therapy outcomes relate to the patient’s social adjustment in the world. Although the memory game described in this chapter may satisfy the need for bookkeeping and numbers, it did not necessarily address concerns for ecological validity raised by some health care providers who fund therapeutic services.

PROBLEMS THAT CHARACTERIZE PATIENTS WITH TBI

The SLP summarized the types of problems characteristic of traumatic brain injury:

… typically, as far as the speech therapist angle, a typical TBI patient has memory deficits, has attention deficits, [and] generally has problem solving deficits. It’s just how severe they are [that varies]. And I and I tell Mark [head of the TBI unit] you know we could make up a menu for our reports often times. With, you know, okay they have a memory problem, how severe is it you know. Pick mild, moderate, severe, profound. And uh problem solving, thought organization, the ability to generate lists and to or to organize to complete a task. You know what d’you do first, what d’you do second, what d’you do third.

The boldfaced portions of this passage reveal the SLP’s tendency to locate TBI internally according to intrinsic, cognitive deficits suffered by individuals: “memory deficits,” “attention deficits,” difficulties with “problem solving,” “the ability to generate lists” and “thought organization.”

The comments of the SLP were consistent with published literature describing patients recovering from TBI. These characteristics include “process[ing] information inefficiently”; “shallow recent memory and poor access to knowledge”; “impaired attention, concentration, and ability to shift attentional focus”; “general inefficiency in processing information”; “inefficient retrieval of information and of words”; “poorly organized behavior and language expression”; and “relatively marked deterioration of comprehension caused by increases in the amount, complexity, and abstractness of information and in the rate of presentation” (Haarbauer-Krupa, Henry, Szekeres, & Ylvisaker, 1985a, p. 311; Haarbauer-Krupa, Moser, Smith, Sullivan, & Szekeres, 1985b, p. 287).

On the other hand, some of the concerns for patients with TBI, mentioned by the SLP, were more interactionally oriented:

Attention. … Are they able to follow along? When they’re not being spoken to directly, are they looking out the window? … The ability to follow in the conversation … from one to another.

[The] pragmatics involved in conversation [are a problem]. You know, the body language. We’ve got ’em heads down on the table. [And] some of them will just push right away from the table, not say a word and leave [in the middle of a conversation]. I mean you’re like wait, wait, wait, where ya’ goin?

The SLP indicated that one of her biggest surprises was that individuals with TBI often did not become fully aware of their “limitations” until after they left the rehabilitation hospital:

… it was so surprising to me at first when people just weren’t aware [of their own problems] even when you’re telling them. … You’re in a closed little world up on the unit. You generally see a transition [to greater awareness about having a problem] after they’ve gone for a TLOA, a therapeutic leave of absence. … They’ll come back early because they couldn’t take it. They’ll say “It was too much and I was getting a headache and I just had to come back here.” If they have an experience [like that] that’s when I’ll start to see a change, when they start to have some real awareness.

THE GOALS OF THERAPY

The overriding goal of the rehabilitation unit, with all its different therapeutic specialties, was to help TBI patients achieve their highest level of “functionality” and “independence” so that their transition back into the social world outside the hospital would be more successful. As part of realizing this goal, the SLP was aware that the therapeutic process was closely tied to issues of identity and identity transformation subsequent to traumatic brain injury. She expressed concern because the relationship between therapy and the identities and personal experiences of individuals was a difficult one to address:

… we’re not trying to make people back into you know high school teachers or whatever it was before … if I have any idea what that is. … You know I’m not one of those people who thinks I’m going to change this person’s life. … [Therapy’s] real functional. So you know if they’re finishin’ up their lunch or their breakfast I’ll go in and you know we’ll talk about what’d you have for breakfast? What’d ya have for lunch? What are ya doin’? … Where ya been? Where ya goin’? Where’s your room. … Tryin’ to do functional things around the unit. … Um things that they’re gonna have to do … activities of daily living. You know if they need something who are they gonna ask if they don’t know? Can they figure it out on their own? You know brushing your teeth uh … If they’re gonna brush their teeth do they know to put the toothpaste on before they start brushing not after? … How is this person functioning in relationship to what they have to do for their daily life? Can they locate information? Can they problem solve? If they go into their room and there’s something in the way, can they figure out what to do?

The rehabilitation was situated within a large metropolitan medical center where patients from all walks of life were constantly being admitted to the unit. Because of this, little was known about the personal life histories and experiences of these individuals prior to their injuries. This, coupled with the belief that therapy would not transform those with TBI back to their pre-injury status, meant that the goals of increased functionality and independence were reduced to a set of objectifiable “activities of daily living,” which did not directly focus on the life situations and experiences of individuals.

To help patients achieve some degree of functional independence, the SLP directed her efforts toward improving memory, attending to conversation, and problem-solving. Here, memory was seen as a skill that could be treated on the periphery of interaction through drills: “We do more direct drill type things where we work on memory … you know that’s not so much interacting with each other.”

Along with these individual goals, the main purpose of group therapy was to facilitate “social interaction and pragmatics”:

I mean this person’s gonna go and no matter where they’re going, they’re not gonna be locked in a little cell by themselves. [The purpose of group therapy is to] help them become the most appropriate at interacting that they can. I mean you’ve got I’ve got all these other individual goals. But overall, as a group therapy [goal], interaction and interaction with other people [is] important because [it] is such a part of our lives. And so many, if you watch on the unit, they isolate themselves … they don’t know how to interact. Many of the patients have no initiation at all. [And] turn taking. Do they know when it’s their turn? … Especially when we do a lot of games … do they know when it’s their turn?

Analysis of the videotaped therapy sessions revealed that efforts were made to realize these different intervention goals by engaging clients in a variety of game activities: “… we do a lot of games … scavenger hunt [and] board games … where we work on memory … and we do some more direct drill type things where we work on memory.” Memory drills, for example, would be nested within games where patients had to remember lists of words. A turn-by-turn description of one of these games—called Going to the Moon—is presented later.

At the same time, because the abilities of individuals with TBI to follow and sustain a conversation were seen as deficient, games provided a structure through which to build interactional coherence.

… we do games [to see if] they know when it’s their turn … turn taking is often [addressed] during the game because often times the dialogue is more directed by us. We ask a question of so and so … and we move from person to person to try and facilitate some interaction.

By defining successful participation according to the preestablished rules of a game, the SLP was in a position to judge the appropriateness of individual contributions to the group topic, and to intervene when necessary. Coherence could be reduced and managed according to the rules of the game, and not the personal experiences and histories that players brought to the activity.

In sum, games could thus be viewed as a means of accomplishing a complex, clinical online agenda—improving memory through drill work and building interactional coherence among individuals.

Models of Language and Cognition

The idea of treating intrinsic problems of mind through various types of drill activities is consistent with certain psychological models of language and cognition that have strongly influenced speech-language pathology as a professional discipline. From this vantage point, language and cognition are seen as internal processes of mind. These processes are like a set of tools to be pulled out of a mental folder and applied to the external, social world:

The mind and its contents have been treated rather like a well-filled toolbox. Knowledge [language included] is conceived of as a set of tools stored in memory, carried around by individuals who take the tools out and use them … after which they are stowed away again without any change at any time during the process. The metaphor is especially apt given that tools are designed to resist change or destruction through conditions of their use. (Lave, 1988, p. 25)

When internal, mental processes, such as memory, break down, the practitioner seeks to repair the breakdown, or help the impaired individual compensate for it. From this perspective, games are a therapeutic means for addressing intrinsic cognitive problems caused by traumatic brain injury in areas such as attention, perception, sequencing, problem-solving and planning, and memory (Deaton, 1991):

Memory skills are tapped by such games as Concentration, Memory, Numbers Up, and Enchanted Forest. These games can facilitate the acquisition and use of strategies such as rehearsal or association. They also lend themselves to teaching the use of external memory aids such as lists, as it will quickly become apparent to the client that his or her performance on the game improves dramatically when this additional tool is available to aid in recall. (p. 205)

Concerns about this type of clinical reasoning can be raised with respect to the cognitive model being applied to intervention. Conceptualizing of the mind as a set of internal tools that remain constant when applied to the external, social world overlooks the interaction between the tool and the situation of its use:

… when “tool” is used as a metaphor for knowledge-in-use across settings, there is assumed to be no interaction between tool and situation, but only an application of the tool on different occasions. Since situations are not assumed to impinge on the tool itself, [the] theory … does not require an account of situations, much less the relations among them. Knowledge acquisition may be considered … as if the social context of activity had no critical effects on knowledge-in-use. (Lave, 1988, p. 41)

Such a view permits improved memory, a part of the toolbox that can be isolated from those social occasions of its use, to be the goal of therapy without addressing the relationship between the game activity and how remembering is displayed in everyday contexts of interaction.

Instead of focusing on the processes in the internal mental toolbox, Lave (1988) proposes a different unit of analysis for examining cognition and learning:

… the whole person in action, acting within settings of that activity. This shifts the boundaries of [cognitive] activity well outside the skull … to persons engaged in the social world for a variety of reasons. (pp. 17–18)

… knowledge in practice, constituted in settings of practice, is the locus of the most powerful knowledgeability of people in the lived-in world. (p. 14)

… [this view] motivates a different set of problems and questions than the study of virtuoso performance and people’s failures to produce such performances. (p. 15)

This situated perspective would suggest an important relationship between the display of cognitive abilities, such as memory, and the social contexts in which they occur. In the Going to the Moon activity presented subsequently, memory was accessed through an alphabetical strategy congruent with the rules of the game, but inconsistent with how the remembering of lists might surface during other types of interaction in the everyday world.

GOING TO THE MOON: MEMORY, THE ROLE OF HUMAN EXPERIENCE, AND FOLLOWING THE RULES OF THE GAME

The reliance on gamelike activities to carry the interactional work of therapy, and the treatment of memory as a skill isolated from the everyday world, were evidenced in the Going to the Moon game. During this game, each person was asked to think of an item they would want to bring to the moon. As subsequent people took their turns, they also had to repeat all the items mentioned previously and then add a new one of their own. The item selected had to begin with a letter that corresponded to successive letters in the alphabet. In other words, the first individual had to name an item that began with the letter A, the second person had to name an item that began with the letter B, and so on. The SLP was oriented toward having the patients verbally repeat a growing list of alphabetically sequenced items, which could be named in successive turns by each individual. At the end of the game, the therapist indicated that the “repetitiveness of the activity and using the alphabet [were] clues” to help the group with remembering the list.

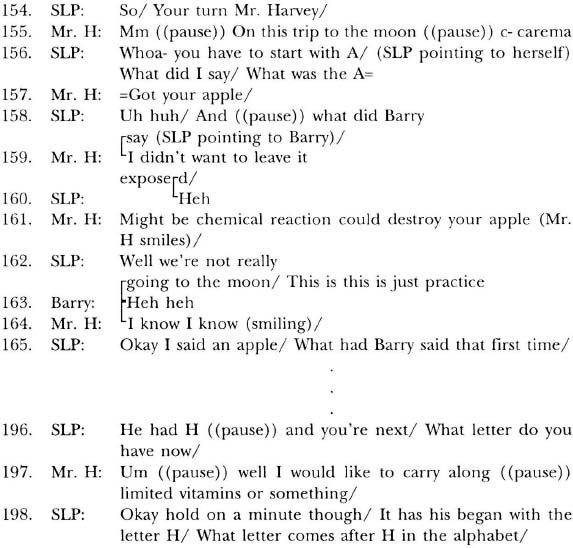

The therapist asked none of the patients why they would want to bring certain items and made moves to limit such discussions if initiated by members of the group. In the following example, Mr. Harvey (Mr. H) was selected as the next participant and told that his contribution must begin with the letter C (turn #121).1

Mr. Harvey began by reiterating the experience on which his memory was to be based: “my voyage is to the moon” (turn #122). He continued by listing items that could be used for the purpose of writing on his journey (turns #126 and #128). At this point, the SLP stopped Mr. Harvey and indicated that he was not following the rules of the game because he did not repeat items mentioned previously by other members of the group (turns #127, #129, and #131). After Mr. Harvey stated (in alphabetical succession) what other group members were bringing to the moon, the SLP indicated her approval (turn #133).

The SLP then attempted to clarify the rules of the game, indicating that Mr. Harvey must constrain his response to something “that begins with the letter C.” Furthermore, his response need not be tied to anything one might want to “really take” to the moon. Instead, his reply “could be something silly,” as long as the item began with the appropriate letter in the alphabet. When Mr. Harvey provided the appropriate answer, “a camera,” the SLP indicated her approval (turn #137). In other words, based on the rules of the game, the appropriate display of memory was grounded in successive letters of the alphabet, as opposed to any imagined experience of going to the moon.

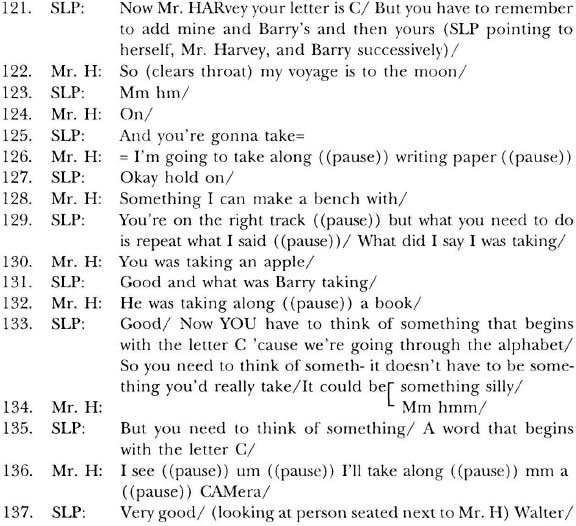

Later in the game, Mr. Harvey tried again, on two different occasions, to tie this memory game to the experience of going to the moon (turns #159, #161, and #197). In both instances, the SLP discouraged this type of remembering:

In turns #159 and #161, Mr. Harvey indicated that he did not want to leave the apple “exposed” because there “might be chemical reaction that could destroy your apple.” The SLP responded, “Well we’re not really going to the moon” and “This is … just practice.” As Pomerantz (1983, p. 72) notes, “well” is one way of “prefacing [a] disagreement … thus displaying reluctancy or discomfort.” In this instance, “Well” prefaced a statement that served to minimize Mr. Harvey’s continued efforts to tie memory to personal experience without respecting the rules of the game.

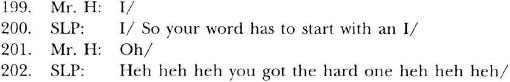

Finally, in turn #197, Mr. Harvey indicated that he would like to bring along some vitamins, presumably because nutrients would be a concern to someone experiencing space travel. The therapist responded by saying “okay.” As a discourse marker, one of the functions of “okay” is to release a participant from a prior turn at talk (Schiffrin, 1987). In speech-language therapy, these markers may simultaneously hold an evaluative function, indicating whether the prior contribution is judged to be appropriate or inappropriate (Kovarsky, 1989b, 1990). In turn #198, the SLP indicated that Mr. Harvey’s contribution was not correct by saying “hold on a minute,” and then redirected him to provide an appropriate contribution based on the next letter in the alphabet.

In all of the cases above, Mr. Harvey attempted to address how the personal experience of going to the moon would relate to those items he would want to bring on the trip. Indeed, memories often surface in interaction as a way of relating personal experiences through the presentation of particularistic details and concrete images (Tannen, 1989). Yet the therapist indicated that this was not how remembering was to be achieved. Instead, the task of remembering was disembedded from personal experience and rooted in a list of words based on the alphabetical ordering of items.

Strict adherence to the rules of this game could be viewed as a competency-lowering communicative practice. By not allowing memory tasks to be grounded in experience, either real or imagined, participants were prevented from using a potential resource for remembering: a resource that some individuals with TBI were clearly able to draw upon in other contexts. Before a different group therapy session began, Larry (a patient) was explaining to a fellow patient about insurance benefits. This description, which related to Larry’s previous experience in the rehabilitation hospital, contained remembrances of prior interactions:

Larry effectively recounted a prior experience that contributed to the overall point of the interaction: that his listener needs to find out about insurance benefits.

There are also instances in which lists may present themselves in interaction (Tannen, 1989). In the following example, a woman is recalling information about an office coworker:

And he knows Spanish,

and he knows French,

and he knows English,

and he knows German,

and he is a gentleman.

(Tannen, 1989, p. 50)

The listed items contributed to the evaluative point being made by the speaker: that she “finds the length of the list impressive—and so should the listener” (Tannen, 1989, pp. 50–51).

The Going to the Moon game is not rooted in experience and the word list does not emerge as part of a larger conversational point. Rather, the list is generated for its own sake during therapy. In this way, memory is isolated from experience and disembodied from larger segments of talk-in-interaction in which remembrances may present themselves. In other words, the particular gamelike practices of this therapy activity provided a context in which communicative incompetencies were more likely to surface, as in the case of Mr. Harvey.

On the other hand, as long as participants were playing by the rules of the game, there were instances of more supportive communicative practices. Below, a misunderstanding about the meaning of the word “edge” becomes a resource for Jay’s successful recounting of what objects he would take to the moon:

Jay indicated that “an edge” was a “golf club.” While the term “edge” fits the rules of the game because it begins with the appropriate letter of the alphabet, it represents a mistake. The golf club Jay referred to is actually called a “wedge.” However, no one in the group mentioned this error. When asked about this error after the session, the SLP laughed and said she had no knowledge of golf and no idea whether or not an “edge” was a club. Furthermore, when Jay stated he would use the “edge” to practice golf (turn #139), he was not admonished by the SLP for relating his contribution to the list to a personal experience. It would seem that as long as the alphabetical rule for participation was not violated, therapy participants could discuss their internal motivations for bringing certain items to the moon.

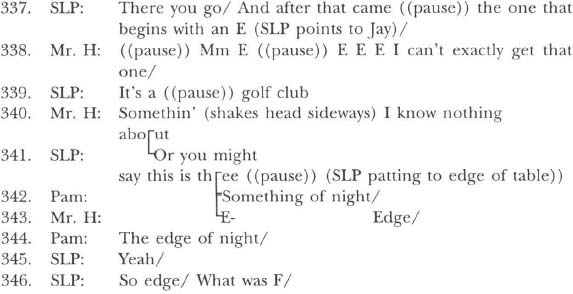

Later, when Mr. Harvey had trouble recalling Jay’s contribution to the list, the SLP provided a hint by pointing to Jay (turn #337) and mentioning that the item was “a golf club” (turn #339):

In turn #340, Mr. Harvey indicated he knew nothing about golf. The SLP then changed the nature of her clue by pointing to the edge of the table which signaled the conventional referent for the word “edge.” At the same time, Pam provided a hint, saying “Something of night” (turn #342), in reference to the soap opera “The Edge of Night” (turn #344). Subsequent to the clues provided by Pam and the SLP, Mr. Harvey produced the appropriate response. In other words, within the confines of this activity, “edge” became a homonym for both a golf club and its conventional concrete definition. To a degree, as long as the players adhered to the rules of the game, word meaning could be appropriated to facilitate memory.

As Jacoby and Ochs (1995) suggest: “relying only on the informational, semantic, and propositional content of words and utterances will fail to get at what utterances might be doing as actions in a sequence of detailed interactional events” (p. 176). Providing clues that were not tied to golf, something outside Mr. Harvey’s claimed realm of experience, was a supportive move within the confines of the game. This example illustrates that word meaning could be brought into play during therapy, as long as the rules of the game were not violated.

DISCUSSION

Ways of remembering tied to personal experience were sanctioned negatively when they violated the alphabetical, listing rules of the game. Because this activity was divorced from how memories surface in other communicative contexts, it had the potential for constraining the display of memory during therapy. In this sense, the manner in which the Going to the Moon game was played could be viewed as a competency-lowering practice. When remembered lists do appear in interaction, they contribute to the overall point of the interaction and are not an end in themselves (Tannen, 1989). During therapy, however, a list was generated for the sole purpose of taxing an area of presumed deficit (i.e., memory) among individuals with TBI. The point of this therapy activity was to recall a list of items according to successive letters in the alphabet, irrespective of relevant personal experience.

This session appeared to be at odds with the overall purpose of intervention. Although the long-term goal of therapy and of the whole rehabilitation unit was functional independence in the social world, activities like playing Going to the Moon disembedded both language and cognition from the communicative practices of everyday life. In doing so, therapy participants were at greater risk for displaying incompetence because they were not allowed to draw upon important resources and purposes for communicating memory found in everyday interaction.

Several facets of therapy provide a ready set of resources for the construction of incompetence. First, in this rehabilitative setting, numerous patients were seen on an emergency basis and little or no information on their premorbid status was available. It becomes easy to overlook personal life experience in planning and implementing intervention when such information is not readily accessible. Second, it would be naive to suggest that individuals with traumatic brain injury have no intrinsic problems. In fact, models of language and cognition within the discipline of speech-language pathology have traditionally led practitioners to remediate these internal deficits by fixing or correcting errors in performance through extended repair sequences. Third, the gamelike activity, which was based on a currently established set of rules, provided a context for (a) building interactional coherence among group members without necessarily having to account for their personal life histories, (b) practicing memory through drill activities like remembering a sequence of words, and (c) divorcing memory from everyday life. In these ways, problems in remembering a list of words could be attributed to the intrinsic propensities of individuals with TBI and not to the rules of the game.

In sum, the particular models of language and cognition that influence the discipline of speech-language pathology—the error-maker expectancy, the complex clinical agenda, and the manner in which intervention is planned and scheduled—all contribute to therapy practices where games like Going to the Moon are constructed. Taken together, these facets of intervention may have provided the resources for divorcing therapeutic interaction from the communicative life experiences of individuals with TBI: a context in which the display of personal experiences and motivations does not help constitute competent performance. This was particularly problematic, given that the overall goal of intervention within the rehabilitation unit was functionality and independence in the social world.

All this is not to imply that both practitioners and researchers within the discipline of communicative disorders are unaware of such contextualization problems. There has been a growing concern that the way in which practitioners have been trained to locate and address problems serves to isolate (or, according to Kent, 1990, fragment) language and cognition from their interactive contexts of use:

Based on a fragmentation orientation, we were trained in speech-language pathology to segment and decontextualize the communicative behaviors we observe and immediately attempt to find deficits within a client’s internalized psychological/linguistic system rather than focus on the full and complex array of variables and behaviors that make up the communicative process. It is this narrow focus … and its resulting orientation toward fragmentation of human behavior that has caused our professional difficulties. Because of this narrow focus, our attempts to address the complex phenomenon of communicative discourse with a superficial and modular approach to description, assessment, and remediation are naive and insufficient. (Damico, 1993, p. 93)

The results of fragmentation have also been discussed with respect to traditional language intervention practices, which:

… emphasize output and quantifying performance (e.g., counting various linguistic structures elicited, arranging reinforcement schedules for target behaviors, etc.). In other words, the essence of therapy is getting the client to do something so that the clinician can say, “I saw it, I counted it, and I reinforced it.” How “it” is elicited and what “it” really means to the client (important questions from a pragmatic perspective) have not been critical issues. (Dejoy, 1991, p. 18)

Realizing that mismatches can exist between the overall goals of intervention and what happens in therapy has led some students of language disorders to call for theories and framewords that are more attuned to language as a communicative practice (see Damico, 1993; Duchan, 1997; Duchan, Hewitt, & Sonnenmeirer, 1994; Kovarsky & Crago, 1991; Kovarsky & Maxwell, 1997; Maxwell, 1993). One common theme they share is echoed by Jacoby and Ochs (1995): “things allegedly in people’s heads—such as cognition and attitudes, linguistic competence, or pragmatic and cultural knowledge—are made relevant to communication through social interaction” (p. 175).

Competence with respect to language and cognition cannot be predicted simply by noting the presence of an internal, traumatic brain injury. Indeed, as the Going to the Moon data demonstrated, therapeutic situations may be constructed in ways that serve to lower the competencies displayed by patients. The manner in which language disabilities are constituted in patterned ways through interaction should be a vital concern for both researchers and practitioners who seek to understand language disorders. It is important for practitioners to recognize that the process of defining a language problem is itself an interactional achievement shaped by the emergent context: a context that includes a number of resources which participants draw on to construct meaning. Failure to recognize this can lead professionals to narrow frameworks for judging the communicative abilities of those who are deemed impaired. On a theoretical plane, models of language that do not address social interactions as a primary concern do little to enhance our understanding of the human world where “people go about managing their identities, their relationships, and their lives” (Jacoby & Ochs, 1995, p. 179).

REFERENCES

Cazden, C. B. (1988). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Damico, J. S. (1993). Establishing expertise in communicative discourse. ASHA Monographs, 30, 92–98.

Damico, J. S., & Damico, S. K. (1997). The establishment of a dominant interpretive framework in language intervention. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 288–296.

Deaton, A. V. (1991). Rehabilitating cognitive impairments through the use of games. In J. S. Kreutzer & P. H. Wehman (Eds.), Cognitive rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury (pp. 201–213). Baltimore: Brookes.

Dejoy, D. (1991). Overcoming fragmentation through the client-clinician relationship. National Student Speech, Language, Hearing Association Journal, 18, 17–25.

Duchan, J. F. (1993). Clinician-child interaction: Its nature and potential. Seminars in Speech and Language, 4, 53–61.

Duchan, J. F. (1997). A situated pragmatics approach for supporting children with severe communication disorders. Topics in Language Disorders, 17(2), 1–18.

Duchan, J. F., Hewitt, L. E., & Sonnenmeier, R. M. (1994). Pragmatics: From theory to practice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Fey, M. (1986). Language intervention with young children. San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press.

Goodwin, C. (1995). Co-constructing meaning in conversations with an aphasic man. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28(3), 233–260.

Haarbauer-Krupar, J., Henry, K., Szekeres, S. F., & Ylvisaker, M. (1985). Cognitive rehabilitation therapy: Late stages of recovery. In M. Ylvisaker (Ed.), Head injury rehabilitation (pp. 311–341). San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press.

Haarbauer-Krupa, J., Moser, L., Smith, G., Sullivan, D. M., & Szekeres, S. F. (1985). Cognitive rehabilitation therapy: Middle stages of recovery. In M. Ylvisaker (Ed.), Head injury rehabilitation (pp. 287–310). San Diego, CA: College-Hill Press.

Hanks, W. F. (1996). Language and communicative practices. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Jacoby, S., & Ochs, E. (1995) Co-construction: An introduction. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 28(3), 171–183.

Kent, R. (1990). Fragmentation of clinical services and clinical science in communication disorders. National Student Speech, Language, Hearing Association Journal, 17, 4–16.

Kovarsky, D. (1989a). An ethnography of communication in child language therapy. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Kovarsky, D. (1989b). On the occurrence of okay in child language therapy. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 5(2), 137–145.

Kovarsky, D. (1990). Discourse markers in adult-controlled therapy: Implications for child-centered intervention. Journal of Childhood Communication Disorders, 13, 29–41.

Kovarsky, D., & Crago, M. (1991). Toward the ethnography of communication disorders. National Student Speech, Language, Hearing Association Journal, 18, 44–55.

Kovarsky, D., & Duchan, J. F. (1997). The interactional dimensions of language therapy. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 28, 297–308.

Kovarsky, D., & Maxwell, M. (1992). Ethnography and the clinical setting: Communicative expectancies in clinical discourse. Topics in Language Disorders, 12(3), 76–84.

Kovarsky, D., & Maxwell, M. (1997). Rethinking the context of language in schools. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 28, 219–230.

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Maxwell, M. (1993). Introduction: Linguistic theories and language interaction. ASHA Monographs, 30, 1–9.

McTear, M. F., & King, F. (1991). Miscommunication in clinical contexts: The speech therapy interview. In N. Coupland, H. Giles, & J. M. Wiemann (Eds.), “Miscommunication” and problematic talk (pp. 195–214). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mehan, H. (1985). The structure of classroom discourse. In T. Van Dijck (Ed.), Handbook of discourse analysis (Vol. 3). London: Academic Press.

Panagos, J. M. (1996). Speech therapy discourse: The input to learning. In M. D. Smith & J. S. Damico (Eds.), Childhood language disorders (pp. 41–63). New York: Thieme Medical Publishers.

Pomerantz, A. (1983). Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: Some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. In J. Maxwell Atkinson & M. Heritage (Eds.), Structures of social action (pp. 57–101). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Prutting, C. A., Bagshaw, N., Goldstein, H., Juskowitz, S., & Umen, I. (1978). Clinician-child discourse: Some preliminary questions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 43, 123–139.

Ripich, D., & Panagos, J. M. (1985). Accessing children’s knowledge of sociolinguistic rules for speech therapy lessons. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 50, 335–346.

Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, R. M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Tannen, D. (1989). Talking voices: Repetition, dialogue, and imagery in conversational discourse. New York: Cambridge University Press.

van Kleeck, A., & Richardson, A. (1986). What’s in an error? Using children’s wrong responses as teaching opportunities. National Student Speech, Language, Hearing Association Journal, 14, 25–50.

1 Transcription Key: / marks the end of an utterance; ( ) nonverbal behavior enclosed in parentheses; ((pause)) double parentheses contain untimed pauses; = indicates latched utterances with no gap and no overlap in between; CAPS indicate increased stress or emphasis; heh marks laughter; [ indicates point of overlap between utterances.