LESSON 3

THINK BIG, ACT SMALL, MOVE QUICK

Go as far as you can see; when you get there, you'll be able to see farther.

—J. P. MORGAN

Building and managing your trajectory involves putting in place a series of manageable steps and goals. Some of these steps, though critical to your ultimate goals and trajectory, may actually be rather small in nature. This should not be construed to mean that grand thinking is not desirable. In fact, it is just the opposite. Big thinking is critical. It just does not normally transpire overnight or by accident. In this lesson you will learn that you must think long-term, but the best path to reach your big goals is often through small actions and quick moves.

Take the home run hitter in baseball. He is fun to watch, because there is a chance that he might hit a big home run, but more frequently he will not. Success for a home run hitter might be getting a hit once every four at-bats, and a home run every ten at-bats. In contrast, the job of a lead-off hitter is to get on base. This difference is at the heart of the Think Big, Act Small, Move Quick strategy. Think big = win the game; act small = get on base in order to score a run; move quick = do it in the first inning, and steal second base to get into scoring position. In doing this, the lead-off hitter maximizes his (and the team's) chance of success, but does not close the door on a big home run every now and again.

In the final and deciding game seven of the 1967 World Series, Bob Gibson was the starting pitcher for the St. Louis Cardinals. He had won two games earlier in the series and picked up where he left off by continuing his pitching dominance in this game. But he did something else: he hit his big home run. His goal never varied—win the game, and do it batter by batter—but his approach and preparation led him to become one of the very few pitchers to ever hit a home run in the World Series. For context, over the course of his career he hit a home run in fewer than 2 percent of his regular season at-bats. Over the course of three World Series he hit a home run in more than 7 percent of his at-bats! What this also illustrates is that not only does a think big, act small, move quick strategy set up victories every day, it also puts you in a position to do so when the stakes are the highest.

There are many examples of people who reached unbelievable heights one small goal at a time, including another well-known instance from the baseball world. On September 6, 1995, Cal Ripken Jr. played in his 2,131st consecutive major league baseball game, breaking the record Lou Gehrig had held for fifty-six years. Ripken of course did this over the course of many years. In a way, he had set 2,131 interim goals on the way to the record. For Ripken, what started as a rather simple goal evolved over time into what became a grand goal. The first goal of Ripken's baseball career was undoubtedly not to break the consecutive games streak, but more simply to make the team and be successful. Early in his career the idea of breaking the record was likely not even a blip on his radar. Eventually the streak came into focus as his number of consecutive games grew over time. Remember this: As you grow in your career you need to keep your eyes open to new and even previously unthought-of goals that present themselves. What once seemed unimaginable will very quickly become quite realistic as you follow your plan.

Similarly, Emmitt Smith—the National Football League's all-time leading rusher—describes in his autobiography how it was actually many small goals that led to his record-setting 18,355 career rushing yards. In every game he set a goal to rush for at least four yards per carry. While he did not reach this every single game, he persevered and would then look to get even more yards the next time. Or think back to Ben Saunders, whose story we discussed in the “Getting Started” chapter of this book. During his expedition to the North Pole he always kept his focus on what was in front of him. He continually broke his quest into little chunks by focusing on reaching the next piece of ice, and the next piece. Through these building steps he reached his goal and covered the full 1,240-mile journey. He thought big with his plan of reaching the North Pole. He started small with each step and chunk of ice. He moved as quick as conditions would safely allow, but no faster. In any endeavor, attempting too much too quickly is a recipe for disaster. Along his journey no individual step was grandiose, but collectively each step led to what was a record-breaking feat. Like Bob Gibson, Cal Ripken Jr., Emmitt Smith, and Ben Saunders, everyone has an inherent desire to be successful. Leveraging think big, act small, move quick will help you in your pursuit.

Applied to work, these examples prove that if you continually play in game after game, and are accumulating base hits, you not only are moving the needle forward, you are setting up a situation where you will also hit home runs. This is a powerful combination. All three elements of think Big, act Small, move Quick (BSQ) must work together for you. The world has no shortage of big ideas; it is short on big ideas that people actually carry out to fruition. Viewing your think big goals through the daily lens of acting small but moving quickly will allow you to realize your goals.

REACH YOUR SUMMITS

History is littered with innovators and explorers who decided to think big and aspire to do something that nobody else had done before them. Mountain climbing is one of the most arduous yet gratifying endeavors for many such adventurers. Scattered across the globe are what are known as the Seven Summits, which consist of the highest mountain on each continent. Despite the highest mountain (Mt. Everest) being successfully scaled in 1953, it was not until more than thirty years later that a single person was able to climb each of the Seven Summits.

This feat was accomplished by the most unlikely of individuals, someone who was not a natural mountaineer. Dick Bass was a fifty-one-year-old businessman with little climbing experience; few would have believed that this white-collar executive would end up being the first person to attain such a significant accomplishment. To do so he had to think big, act small (though in this case “small” was each mountain!), and move quick. “Quick” was particularly important because of seasonal climbing windows for some of the peaks, not to mention the fact that at least one other climber was also trying to become the first to climb each of the mountains.

To reach such a bold goal took great preparation and training. Bass's “think big” was to climb all of the mountains: his “act small” was to prepare for and tackle one mountain at a time, and his “move quick” was to accomplish his mission before his window of time was over or someone beat him to it. 22,835 feet. 20,320 feet. 19,340 feet. 18,481 feet. 16,067 feet. 7,316 feet. 29,029 feet. These are the elevations of each of the seven mountains in the order that Bass climbed them, and it is another way of illustrating that successful trajectories are not always constant.

In his case he actually went downward through the mountain elevations until he reached his final—and highest—summit at the top of Mt. Everest. He started with Aconcagua in South America, then McKinley (Denali) in North America, followed by Kilimanjaro in Africa. He then turned to El'brus in Europe, Vinson in Antarctica, and Kosciusko in Australia, before finishing with a successful summit of Mt. Everest in Asia. He did not start with the smallest and then work his way up; instead he followed the plan he had put together to maximize his chances of reaching his trajectory. The numbers, though, do not convey the failure and persistence along the way. It actually was not until Bass's fourth attempt that he succeeded in climbing Mt. Everest. So while he failed three times, he continued to persist and was able to reach his ultimate trajectory. Bass reminds us of Lesson 2: It is persistence that is the real differentiator when situations are most difficult.

Like Dick Bass you will find that it pays for you to think big when you consider what you want to achieve. No matter how hard you try you will never be able to do everything at once. Over time, though, you will be able to accomplish that which you seek, by tackling one mountain at a time. Each mountain will come with challenges, but when you break these into the respective pieces it will become easier for you to meet and overcome each one—and to do so quickly.

GOAL MANAGEMENT

All of this sounds good, but how do you actually go about it? A critical element of BSQ that enables this to happen is to set goals that serve as guideposts along your trajectory. This is supported by goal-setting theory, which is one of the foundations of organizational psychology. Though there have been thousands of studies on goal setting, the body of work as it relates to individual performance can be summarized quite simply through a few distinctions:

1. A goal is better than no goal.

2. A specific goal is better than a broad goal.

3. A hard and specific goal is better than an easy goal.

If you make it a practice to routinely establish goals you will have covered the primary tenet of goal theory. And if you make your goals specific (e.g., “become a partner in my law firm by the end of next year” versus “be successful at work”) you have then knocked out the second tenet. Now you get to the more complex part of setting goals. The research is clear: difficult but attainable goals will consistently result in the most success. This has been an enduring finding that has been replicated in countless settings. On the one hand, if you set goals that are too difficult the goal becomes unrealistic and you lose motivation and fail to achieve it. On the other hand, if you set a goal that is too easy you will have no problem reaching it, but in doing so you may settle for something less than your best effort and thereby miss out on what could have been a more profound accomplishment. If in your career and life you only set goals that are easy, you will shortchange yourself and thereby not reach your true limits. You therefore must find an optimal balance of what is hard but realistic versus realistic but too easy.

A second part of this is determining the right time horizon for your goals. This is known as goal proximity. If you set a goal that is too distal (far in the future), you will reduce your chance of reaching it. More specifically, proximal (near-term) goals, which you can set as part of move quick, are more likely to be achieved than are distal goals. Because they are by nature shorter term, proximal goals tend to be smaller than bigger goals. As an example, a proximal goal at the start of the year might be develop restaurant business and opening strategy by June. A more distal goal would be opening the restaurant. Through attaining one proximal goal after another you accomplish two very important things: 1) You move closer to your ultimate goal; 2) You succeed in these and in turn continue to grow your confidence in your abilities. Bear in mind that proximal goals will continue to evolve as you progress. When you start a project at work, for instance, what was once a very distal goal will become a proximal goal as you move through the milestones of the initiative.

By setting goals and focusing on proximal and interim goals you will find that you are giving yourself something else that we've learned is so important: feedback (Lesson 1). As you progress you will either succeed or fail. Either of these outcomes will let you know what worked and what did not. You will feel progression, and in doing so you will gain more self-efficacy. By now you should be beginning to realize how all of your actions are interconnected. Each little success will create a stronger mindset and prepare you for more success, which will in turn make you inclined to persist even harder in the pursuit of your goals.

Weight loss is a commonly used example of how to set goals. If you think about losing weight but never set an actual goal, it is unlikely to happen. If you decide broadly, “I want to lose twelve pounds,” you will likely lose less weight than if you set a specific goal to lose one pound every month for a year. If you really want to lose five pounds, but only set a goal to lose one pound, you will likely stop there. By setting a goal of five pounds you will undoubtedly achieve more. Even losing just one additional pound would actually constitute a 100 percent improvement over losing only one pound.

You can similarly leverage goal-setting principles in your career to help guide your trajectory. As you chart your trajectory you must consider the importance of ensuring that you set goals that are specific and attainable yet difficult. If you have no goals it will be very hard to have any idea of what you need to work on. If you have a broad goal, such as wanting to open a business, you won't know where to start. If you have an easy goal, you run the risk of selling yourself short. You therefore need to create a plan that includes a series of goals. If you wanted to open a restaurant, for example, you might start with the plan shown in Table 3-1.

Deciding to open a successful restaurant is an example of thinking big. Wrapping a one-year time frame around it will underscore the need for you to move quickly. Each of the goals in Table 3-1 can be viewed as a guidepost that can be considered part of act small, but each of these goals is very important. In fact, you would likely fail if you missed any of these act small goals. Moreover, each of these when considered individually becomes more manageable and allows you to tackle realistic yet difficult tasks in pursuit of your goal. Hopefully you can see that breaking it down in this manner would make it much easier for you to stay on track than would simply setting a goal to open a restaurant. And when you move quickly you will navigate through all of the goals that lead up to opening the restaurant. You can now see how this all builds and can work together.

Table 3-1. Think Big, Act Small, Move Quick Plan

| Think Big | Act Small | Move Quick |

| Open a successful restaurant within one year | ||

| Develop business strategy | By June | |

| Decide on business name | By July | |

| Obtain financing | By August | |

| Finalize restaurant location and sign lease | By September | |

| Begin interior remodel and construction | September 15 | |

| Hire lead chef | October | |

| Develop menu | By end of the year | |

| Hire and train staff | January–February | |

| Grand opening | March 15 at 6 p.m. |

Let's now put this lesson in the context of the early stages of a career. Perhaps you're a recent college graduate who aspires to one day be CEO of a company. This is great, but how do you get there? BSQ and goals can be leveraged to help you reach your aspiration. This will give you milestone goals and provide clarity along the path to achieving each one. By defining sequential goals (act small) and readily progressing toward these (move quick) you will greatly improve your chances of achieving your goal of one day becoming CEO. If you do not follow this progression you will more likely end up becoming overly reliant on luck and chasing an amorphous aspiration.

Regardless of your career stages, goals can be used to guide your development. It is hard to get a job without a plan to get there. Goals can be used to frame the plan you need to put in place to ensure that you obtain the experiences you need to prepare for your next job. Within this you can also create goal targets for areas in which you need development to improve your skills. Maybe it is taking a course on strategic leadership, or seeking an opportunity to work on a project in a different function. Regardless of what specific actions align with your needs, putting goals in place will make it easier for you to hold yourself accountable for reaching them.

SMALL BITES

As you learned in Lesson 2, patience is critical to your success and is an essential element of the think big, act small, move quick strategy. Unfortunately, patience can be hard to master and is one of those traits that tend to improve with age. When you use the move quick approach you will find that you are continually able to make incremental progress toward your larger goals. These “small bites” will make it easier for you to manage obstacles along the path to a grand goal. In doing so you can avoid making sloppy mistakes or overreaching. At the same time, when you split up your goals and trajectory with this approach, it can seem that progress does not happen fast enough. This is not the case.

Evolutionary thoughts and progress will result in revolutionary accomplishment, and you will be amazed at how rapidly this can actually transpire. As your successes continue to build you will feel that you are moving quickly along the path to your goals. On the other hand, if you are at step one and your goal is to reach step ten it may seem that you are walking in place if you have no other steps pre-specified along your path. If you have sub-goals for steps two through nine it will seem that you are moving so much faster. Many of us can relate to a long road trip that you chunk up into various milestones. This process follows the same principle. A ten-hour trip might have a bathroom break at two hours, a countdown to the halfway point at five hours, a food stop at seven hours, etc., and then all of a sudden the trip seems to have moved along much faster than it otherwise would.

There is a classic psychological study by Walter Mischel of Stanford University in which children were each given a marshmallow to eat. They were told, however, that if they waited fifteen minutes before eating the marshmallow, they would be given a second one. Seems simple enough, with no long-term impact, correct? Turns out this experiment and its implications are not as simple as they might initially seem. Mischel followed these children for many years to track their subsequent progress in life. As time went by, the children who had resisted the initial temptation to eat the first marshmallow were found to have higher SAT scores and were more successful in their careers. Something as basic as delaying gratification for fifteen minutes actually mattered.

Imagine that for a second. The simple delayed gratification of waiting to eat a marshmallow was found to reliably predict success later in life. Eating the marshmallow immediately would have been easy—and fulfilling—but choosing to wait fifteen minutes resulted in something even more fulfilling because a second marshmallow would then be given. Keeping this in mind will benefit you throughout your life and career. The gratifying dessert you eat now will lead to a need for more exercise later. The shortcut you opted to take at work will lead to needless errors found later. Saying something off the cuff that gives you momentary satisfaction will be something you regret later. Many people choose to eat the first marshmallow as soon as possible at every point in their careers. Doing so can result in taking new jobs solely for immediate tangible gain but will not enhance your portfolio of experiences. By waiting you can eat the right marshmallow at the right time. Move quick, but be patient in making the right moves. Do not move for the sake of moving. And do not mistake activity for purposeful action and meaningful progress. It's important to move quick, but it still needs to be the right move.

DISTRACTED DECISION MAKING

The brain is amazing, and new findings continue to emerge demonstrating how powerful it really is. We rarely think about thinking, but despite this the brain continues to do so for us. Recent research from Carnegie Mellon University has uncovered a very interesting finding in this area. It supports the importance of the “move quick” aspect of this strategy by underscoring that overthinking decisions can lead to suboptimal outcomes. When you overanalyze something, you not only can become stressed and confused, you also lose valuable time.

What the researchers found was that decision making can actually be improved under conditions in which individuals are distracted. They found that by distracting people from the decision at hand, the subsequent decisions were better. This finding was discovered during an experiment in which the researchers shared features of four different cars with people, and then gave some of them a task for a few minutes to distract them from thinking about which car was the best option.

Based on the results of the brain imaging, the researchers noticed that the portion of the brain that was processing the information continued to remain activated and learn, even while the person was engaged in a different task. This suggests that you can let your brain process complex information even when you are not thinking about it. This unconscious activity can lead to better decision making.

When you think too much about something you can get lost in the volume of data and options, which leads to paralysis by analysis. Your indecision then becomes a decision because you fail to decide in a fast enough manner how to proceed. The results lend scientific support to the “go with your gut” model of decision making. Do not overthink issues. If you find yourself overwhelmed or confused by something, stop overanalyzing it. Sleep on it or go do something else and then make the decision when your mind is freed up.

This is further supported by a classic decision-making study that looked at specifying the thought processes connected to the reasons behind choices that people made. In the experiment the authors asked people to taste and rate jams. Those who did so quickly had ratings very similar to those of expert tasters. The participants in another group were asked to provide the reasons for their ratings. When they did this they began to overthink and change their decisions, which resulted in very little similarity to the choices of the expert raters. But this was with jam. Would it also apply in a more high-stakes decision-making scenario? To check this the authors conducted a second study in which students had to make decisions about courses to take for their upcoming sophomore year. As with the first study, the students who were asked to justify their selections chose inferior options. Overthinking once again led to less effective decision making.

The need to make fast decisions does not mean you should make rash decisions. You still need to base your decisions on logic and sound reasoning. However, when you are torn between multiple options, do not ruminate for too long. You likely already know the right answer and are simply spending time trying to find more supporting evidence. If you are at this point, you need to make a decision and move on. If you do not do so, others will move on, and move out in front of you.

Intel learned this the hard way. Intel is famous for the computer memory chips that it developed and that became the backbone of its business in the early 1980s. Yet it is memory chips that could have put the company out of business. Why? Because the company hung on to them as its core business for too long, when what they needed at the time was a decisive decision to expand into other areas. As Japanese competitors flooded the market with cheaper—and better—alternatives, Intel's profit in this area began to decline. Many other companies in this line of products went out of business as a result, and Intel was nearly one of them. However, after a candid conversation in 1985 with Gordon Moore, Intel's chairman and CEO at the time, Andy Grove (who would succeed Moore as CEO) decided that it was time to let go of memory chips and move on to microprocessors.

The path to this decision was quite straightforward, even if the path from that point on was very difficult. During the conversation Grove asked Moore what would happen if they lost their jobs and a new management team were brought in. Without hesitation Moore stated that a new team would move Intel out of the memory chip business. In hindsight this may seem obvious, but at the time it was asking a business to turn its back on what had been its foundation and identity as a company. Moore knew, however, that it had to be done to not only survive, but to grow to an even better place.

At that point memory chips were so central to the business that thousands of employees were dedicated to creating them. In total, more than 7,000 employees were laid off as Intel moved development and production away from memory and toward microprocessors. Had a decision been made earlier, a more gradual—and potentially less disruptive—transition could have been made. Grove estimated that the turnaround took about ten years to accomplish.

With the pace of change occurring in many industries, your decision-making frame of reference is more important than ever. As the speed of change increases, the need to move quick rises as well. If you are in a slow-moving industry you may have a bit more time, but nevertheless, do not rest for long. Let's consider this in the context of your industry. If you work in the railroad industry, for instance, you may be able to spend more time processing major decisions and potential changes in direction. If you are with an Internet start-up company or stock brokerage, however, waiting an equivalent amount of time can easily lead to missing out on a major opportunity.

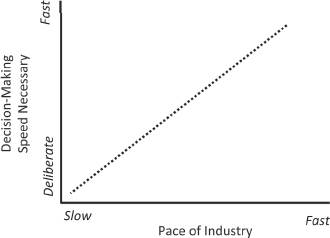

In the technology sector the speed of the industry is tremendous and is a factor that must be considered in decision making. Your decision-making frame of reference can be viewed along a continuum based on the speed of industry and the size of the problem at hand. These factors will help guide how quickly you must move with your decisions. Figure 3-1 illustrates the fact that as the pace of your industry quickens, so too must your ability to make quick decisions. You must be aware that the pace of industry is not static. Whereas technology continues to move at breakneck speed as a whole, certain segments will slow down, while others will accelerate.

Figure 3-1: Decision-Making Slope

Consider Internet browsers. While these continue to evolve and improve, the speed of innovation has stabilized compared to when they were introduced. But other areas are moving faster than ever, and decision-making delays must be avoided. I think one of the most fascinating inventions ever is the 3D printer. When I first began to read about the concept (and I now wish I would have bought stock right then) it was hard to fathom that such a technology was even possible. It was surreal to imagine that you could send something in a manner similar to an e-mail or fax and then thousands of miles away a solid object would be generated. The range of uses runs from simple things like creating plastic prototypes to more complex projects such as building cars and generating organs for human use, and even more futuristic thinking such as applying this technology to build command posts on the moon or even Mars! This exemplifies thinking ahead and adapting to changing conditions and capabilities. I am not suggesting that you need to invent the next technology that changes the world, but you do need to recognize that you cannot always dwell on decisions for too long. Because the uses of 3D printing are so vast, it is not entirely clear how this ability will be fully leveraged. What is clear is that those who move the quickest will have the greatest advantage in this new market space.

MILITARY PRECEDENCE

Top military leaders are very adept at using the principles of think big, act small, move quick. Napoleon Bonaparte, who is widely regarded as one of the most successful military leaders in history, leveraged this principle when he sought to use military might to relentlessly expand the footprint of France. In what is regarded as one of the most profound military campaigns in history, Napoleon led his troops to victory at the Battle of Austerlitz. During the battle he cemented victory over an alliance against France that consisted of Austria, Great Britain, Sweden, and Russia. This group of countries, collectively known as the Third Coalition, was the last major barrier to Napoleon and France obtaining nearly full European dominance.

When you consider the path that Napoleon followed to victory, you will notice that he leveraged the principles of think big, act small, move quick. Over a period of roughly twenty years he waged countless battles, involving millions of troops. Napoleon utilized speed and flexibility as a main tactic as much as possible. He was notorious for requiring his troops to make difficult marches of great distances in extreme conditions in order to reach the enemy at a place of his choosing. Doing so kept his adversaries guessing and enabled him to create an element of surprise.

One of the great aspects of being decisive is that it allows you to remain on the cutting edge. Others will spend time trying to catch up and figuring out what you are going to do next. They will look to you as a leader. You too must begin to think in this way. When you identify up front what your goals are, you can build your career strategy around them. Beyond recognizing the need to act quickly on the battlefield when the stakes were the highest, Napoleon also knew the importance of doing the same for personal career decisions. At one point early in his trajectory he was purportedly given three minutes in which to decide to accept a new military command. He accepted and from there launched one of the most chronicled military careers in history.

The ability to make quick and effective decisions—particularly under difficult situations or when the stakes are high—is a hallmark of successful leaders. Looking back on their careers, rarely do leaders profess that they regret making a mistake, unless the mistake was not acting quickly enough. Most leaders in retrospect will say that they regret the decisions they did not make fast enough. If they would have made faster decisions they would have been able to capitalize on more opportunities. You will have one large decision to make (think big) and then will need to make many small but quick decisions (move fast) along the way.

SMALL STEPS ARE BIG STEPS

All three elements of think big, act small, move quick must work together for you. As you move forward you should remember that your capabilities are only as good as your ability to execute. Many people have the capability to succeed, but fall short on execution. This failing is largely based on people not having a clear and realistic plan. The result is overshooting and trying to do too much at once, thereby doing nothing well. This is not to imply that you should not take risks. Small steps do not necessarily mean small risk. If all you take are average risks, you will likely obtain average results. The real magic is in identifying risk and then taking the right size steps to mitigate it.

In his book Little Bets, Peter Sims discusses the idea that smaller incremental progress serves as a stepping-stone for extraordinary breakthroughs. By tackling these little bets, Sims states, you allow yourself to learn quickly. Whether the learning leads to success or failure, you can use that information to recalibrate and plan your next step forward. As stated at the outset of this book, success rarely happens overnight. When you think of a little bet, you think about something that you would like to attain, but that in and of itself seldom will be life-changing. However, as you continue to amass victories through a series of little bets, you will see great change in your life. In addition, little bets—like proximal goals—serve another critical function. They act as a reward and build the self-efficacy that is so important. The rewards then become a motivator to persist even further.

In more practical terms, let's consider again a goal to lose weight through dieting. Successful dieters are experts at this approach. A dieter thinks big with an overall weight-loss goal, starts with small initial goals (the little bets), and doesn't delay in beginning the necessary efforts. People often like to brag about going on a diet and talk about how much weight they plan to lose. This seems insignificant, but is incredibly important. Telling others about your goals can actually increase your likelihood of reaching them. When you tell others, you are creating an implicit contract that you do not want to break. People have a general dislike of telling others that they did not follow through on something. The moment you tell someone about a goal, you have just strengthened your commitment to yourself, and created a type of contract with the person.

CONCLUSION

When you follow the BSQ approach along your trajectory you will feel yourself gaining momentum. You will feel that something that seemed quite difficult is actually very manageable. You will have the confidence to get there. Your accomplishments will grow, as will your belief in yourself. As this transpires you will find that you are almost unknowingly thinking bigger and bigger as you take on new challenges in your life and career.

You will find yourself spending less time anguishing and dreaming, and more time doing and accomplishing. What you once viewed as a big bet will soon seem so realistic that in the future you will think of it as a little bet.

Now take a moment to complete your next exercise before moving on to Lesson 4.

EXERCISE

Find an example in your life or job of a large upcoming goal that is very important for you to achieve. Think through the goal in detail and then use the following table to create your own think big, act small, move quick strategy, similar to the one in Table 3-1. Putting this on paper will make it more clear how you will be able to attain your big goal. If you reach a point at which you get hung up with a difficult decision, set a time frame for yourself to make the decision and then move on.

| Think Big | Act Small | Move Quick |

NOTES