LESSON 5

AVOIDING THE STAGNATION TRAP

That some achieve great success, is proof to all that others can achieve it as well.

—ABRAHAM LINCOLN

The thirty companies that make up the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) are often thought of as the gold standard when it comes to top organizations. They are chosen based on their past performance and success. These are the blue-chip companies that set the standard of excellence for others. Despite this, you might be surprised to learn that the DJIA is notoriously fickle when it comes to stability. Instead of remaining constant, the companies included in it change quite frequently. In fact, the companies in the DJIA have changed forty-eight times since its founding in 1896; only General Electric remains as an original member. As of 2012, less than half of the companies (thirteen to be exact) had been added before 1990. Another way to put this into perspective is that more than half of the organizations were replaced in the past twenty years.

If these organizations have had such successful performance track records, why is it that this group of great companies changes so much? Even massive companies such as General Motors and Citigroup—leaders in their industries—declined and were removed from the DJIA. This often happens because these companies stagnate and fail to maintain the significant advantage they previously held over their competition. They typically lose that edge—and sometimes fail entirely—because the leadership did not adapt to changing conditions and chart a proper trajectory to avoid what we call stagnation. Instead of constantly searching for ways to stay ahead of the curve, these companies lost their way. It is easy for the DJIA to maintain stability and avoid stagnation because underperforming companies can be replaced with better-performing companies, thereby maintaining more apparent stability.

Unlike the DJIA, you do not have a similar ability to almost instantaneously swap something out if it is no longer working. If your house loses value, for example, you cannot maintain your equity by exchanging it for a house whose value is equivalent to your original purchase price. The same principle applies in your career. It is therefore essential that you continually map out your own trajectory so you will not lose the progress or career capital you have gained. You will need to avoid complacency in order to avoid decline. You must create and maintain your own premium at work. The consequence of not doing so is that your organization could “swap” you for a better-performing employee. You will be able to prevent this outcome by ensuring that you never become stagnant.

This is particularly relevant when you consider that in many high-growth industries and companies the requirements of your job can quickly overtake your current skills. More specifically, a change in job performance expectations can easily outpace the speed of your own skill development if you are not careful. This will require you to constantly expand your skills and identify ways to improve. Without this continual growth, and at times reinvention, you run the risk of stagnation, which is counter to the positive concepts we have covered.

A key element in avoiding stagnation is to be aware of what you need to change in order to stay ahead. If you are not careful, your past success can easily become your biggest impediment to sustained success. In addition to not letting your past success prevent your continued change and growth, you must break unproductive habits and reinvest that energy into productive pursuits. The extra energy you exert to expand your skills will pay great dividends and enable you to remain ahead.

STAGNATION IN CONCEPT

Stagnation can be defined as a failure to develop, progress, or advance, which has the effect of leading you down a negative trajectory. When you stagnate you are in a state of decline. The decline can be gradual or abrupt and can be viewed either in comparison to others or to the trajectory you were once on. Unfortunately, when this process occurs gradually the changes can be subtle and hard to notice until you are long down the path. When you place this concept in the context of your career it has enormous implications. Rarely, though, is there even an awareness or discussion of stagnation in the workplace.

Sometimes the decline is of your own doing. Maybe you did not get the promotion you wanted; maybe you no longer enjoy your job; maybe there was another reason. Other times it has to do with the pace at which you are learning and adapting compared to others. What often happens is that your skills are not keeping up with changing conditions, and others are moving forward while you are moving downward in comparison. This is a very important point for you to consider. You can do exactly the same thing that you have always done successfully and still stagnate. It happens because others are progressing and building their skills at a faster rate than you are, which in the end means you are actually losing ground.

Stagnation is sometimes confused with being at a plateau. However, as we discussed in Lesson 4, plateaus are not necessarily always negative. This fact is the key difference between stagnating and reaching a plateau. Unlike a plateau, stagnation will always have negative consequences because it results in a deterioration of your skills, either directly or indirectly. When your skills deteriorate you provide others with a prime opportunity to overtake you. At times this can be very hard to notice because you can be somewhat sheltered at work. In other words, your most immediate comparison is to those around you.

In order to avoid stagnation you also need to keep pace with changes in the environment and the competitive landscape beyond your job. As discussed in Lesson 1, oftentimes people are so focused on the duties of their job that they forget to look around to see what is changing now or might soon be. Though these changes may not seem important today, they could quickly become very relevant to your continued success. To help avoid stagnation remember to take into account all of the rings in your feedback knowledge circle (Figure 1-1). Input from each of those areas is valuable for keeping up with what is happening around you.

It is essential for you to realize that avoiding stagnation is directly under your control. This actually applies to individuals, teams, organizations, and even entire economies. Indeed, Zanny Minton Beddoes wrote in the Economist that 2012 could be the year of self-induced economic stagnation. She relates economic policy problems—particularly in Europe—to a series of preventable reasons. Beddoes argues that even in cases in which leaders know what should be done, they continually avoid making important changes in order to avoid the possibility of undermining others’ confidence. She lays out reasons why the global recession will last longer than necessary because of avoidable errors.

Avoidable errors are just that—avoidable. Avoidable does not mean that it will be easy, but it does mean that you can prevent it. An avoidable error can take the form of an unnecessary mistake, delaying or failing to make a decision, neglecting to learn from the past, or not adapting to a changing environment. Consider this against the economic stagnation that Beddoes writes about. Governments are not moving quickly enough, nor are they addressing the problems with the right magnitude and fortitude. Rather than making the larger changes that are necessary, Beddoes says, leaders continue to take the safe but ineffective middle road with their proposed solutions. Use this as an example of what not to do in your effort to prevent or move past stagnation. Sometimes little tweaks will be sufficient, but many times you will need to make big changes in order to stay ahead. Do not be afraid to take calculated risks in this regard. As is true with the economy, you may be able to plug along with safety, but eventually it will catch up with you.

TYPES OF STAGNATION

There are two types of stagnation you need to be aware of and elude. The first is known as intrapersonal stagnation, and the second as interpersonal stagnation. While both can be dangerous to your career, you particularly need to be careful to avoid intrapersonal stagnation. If you ever feel that you are stalled in your career, or that things are not moving fast enough, you should quickly attempt to determine whether one of these types of stagnation is the reason.

The state of intrapersonal stagnation is self-induced and will result in your proceeding on a negative trajectory for a period of time. It often begins to take hold at stages during your career when self-doubt creeps in. This could happen because you are uncertain about a particular job or project. It also occurs when you spend too much time reevaluating what you are doing and become mired in uncertainty over which direction to take next. You become entrenched due to that uncertainty, and your excitement and interest in your work then begins to decline. If you are not fully vested in what you are doing it becomes all too easy to fall into a rut and let your performance suffer. This is intrapersonal stagnation. It is driven by events that are fully under your control, and is not directly impacted by external events or conditions.

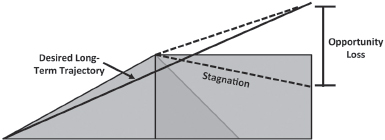

When you consider intrapersonal stagnation in the context of your trajectory, you can see that it will always lead in a downward direction. Figure 5-1 illustrates what occurs when intrapersonal stagnation develops. You have a desired trajectory, and then you allow an event or events to derail it. This could be brought on by an internal situation or by external events such as an industry downturn and the fear of layoffs. The solid line represents your desired long-term trajectory; the top dotted line represents how you were trending before the event; and the bottom dotted line shows what actually happened after the derailing event. What you can see is a large gap—or opportunity loss—from where you were trending with your trajectory to where you actually are. What this underscores is that your opportunity loss is not the difference from the point at which your stagnation began. No, it is actually the difference between where you are now and where you would have been had you not allowed yourself to become derailed.

Figure 5-1: Intrapersonal Stagnation

Alyssa, who worked for a large international conglomerate, succumbed to intrapersonal stagnation. She believed she had a product proposal that would generate millions of dollars in incremental sales and spent a great deal of time studying the market and developing a strong business case. Her approach was meticulously detailed, and there was very little to pick apart. She had supporting market research and focus group data from existing and possible future customers. The financials looked strong. When Alyssa shared the proposal with the business development management team she received a good response and was asked to come back with some additional information in one month. She left feeling very confident that her idea would be approved after the next meeting.

When Alyssa returned with the follow-up proposal she was stunned that the response she received was much less enthusiastic than the first one had been. In fact, what she encountered was more like resistance. Even though she had what she thought was a bulletproof proposal, it was rejected during the actual meeting and she was asked to no longer pursue it. Alyssa felt misled and could not understand why this happened. She started to develop her own “story” about what had happened, and quickly began to feel that management was out to get her and wanted her to fail. Consequently, her once positive attitude started to turn negative. During this time her work performance suffered and others began to try to avoid her at the office. She started looking for a new job and left the company just a few months later.

What Alyssa did not account for in her story was that during the month after her initial presentation a large product recall and negative publicity had impacted one of the company's key products, which was in the same product category as her proposal. She viewed the rejection of her proposal as management not listening to her ideas or not appreciating her contribution. It was just the opposite. Management really did like her proposal, but the timing was no longer right for it. They liked it enough that her suggestion was fully adopted shortly after she left the company and was well received in the marketplace. As Alyssa projected, it did in fact generate the expected amount of incremental income for the company.

Though the product took off well, Alyssa's personal trajectory stagnated when she left. The job she took was very similar to her previous job, and instead of developing new skills most of her time was spent learning the new company, building relationships, and reestablishing herself. As a result, her trajectory unnecessarily went down for a period of time. In the context of Figure 5-1, she could have maintained the top line, but she let an event lead her to stagnate and start down the path in the lower dotted line. Had Alyssa taken time to more fully understand the dynamics surrounding her proposal she may have avoided stagnation. Her mistake was similar to the one Jan made when she went through her company's promotional process (Lesson 1). If Alyssa had simply asked anyone a clarifying question about why her proposal was not adopted, she might have quickly found out that it was not because of something she had done wrong.

Though it is not as damaging to your career as intrapersonal stagnation, interpersonal stagnation is also something you need to be aware of and try to prevent. If intrapersonal stagnation is about independently allowing yourself to lapse, interpersonal stagnation is about allowing yourself to fall short compared to those around you. It occurs when external conditions and competition change more rapidly than you do.

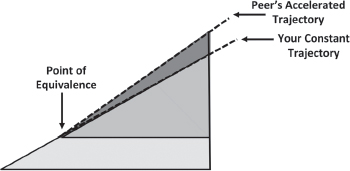

Figure 5-2 shows the consequences of interpersonal stagnation. Let's say that you and a peer are in the same job and are generally equivalent performers. Then a market advancement or organizational change that requires a modification or innovation of skills comes along. You, on the one hand, do not sufficiently notice this need and keep doing the same thing that has worked for you in the past. Your peer, on the other hand, realizes that conditions have changed and quickly adjusts. Even though your own general performance trajectory is the same, it in effect has diminished because of the changed conditions. The trajectory of your peer, represented by the upper dotted line, can be compared to yours in the lower line. The gap between the two shows how you have now stagnated in comparison. In other words, you are still doing well, as illustrated by your positive trajectory, but you lost your point of equivalence and are now trending lower than your peer.

Figure 5-2: Interpersonal Stagnation

Interpersonal stagnation can occur at both an individual and organizational level. Consider Netflix and its impact on Blockbuster. Almost since its inception Netflix has been a darling to investors and welcomed by audiences at home who wanted to watch movies in a convenient way. Netflix was conceived in part because its cofounder, Reed Hastings, had a disdain for the late fees charged by traditional brick-and-mortar movie rental chains such as Blockbuster. What started as a movie delivery service for DVDs has continued to evolve in order to keep pace with—and even drive—changes in technology and consumer needs. Netflix could have maintained a strong plateau and remained the market leader in DVD delivery service, but the company realized that to stay ahead it would need to constantly adapt and change.

One of the major shifts the company made was to expand its number of offerings, and to also include the option to download various televisions shows in addition to movies. Early on Netflix recognized the changing technology landscape and expanded its service offerings to include the ability for people to download and stream movies from their home computers, and then even from mobile devices. More recently Netflix moved into creating its own entertainment content, starting with the acclaimed series House of Cards.

Hastings has been incredibly adept at finding opportunities where others did not realize a need existed. He was finding blue oceans (Lesson 4). Perhaps more important, he has not become complacent with any of the Netflix successes. He continually has probed and done research to find ways to improve and further expand his business. In Demand: Creating What People Love Before They Know They Want It, Adrian Slywotzky reviews the rather ominous start to Netflix, when subscriber growth was anemic. Only San Francisco—the site of Netflix headquarters and its distribution center—had a decent subscription rate. Hastings and his team needed to know why, so they collected subscriber data to understand differences across customer bases. What they found was that subscribers in San Francisco loved Netflix because they received their DVDs so quickly due to the proximity of the distribution center (DC). Based on the results of the data Netflix began to open more DCs and found that subscriber rates in the areas near those centers soon jumped.

Compare this to Blockbuster, which was the preeminent movie rental company in the United States. Instead of recognizing and going after the opportunity in this new area of online content, the company simply stayed its course, rested for a while at a plateau, and then fell quickly into stagnation. What might have been a relatively modest investment if done sooner instead became a massive effort by Blockbuster to catch up to Netflix. Ultimately the effort failed. By the time Blockbuster tried to gain a foothold in this emerging market space it was so far behind that the company had to file for bankruptcy.

In The Innovator's Dilemma, Clayton Christensen explores this type of problem at the organizational level through his insightful analysis of why many successful companies fail. He states that these companies are doing the right things, but they paradoxically fail for just that reason. They fail for doing more of what made them great in the first place. Meanwhile, other companies are moving past that point and taking advantage of new approaches, enabling them to jump ahead of the competition. Companies that fail in this manner serve as examples of interpersonal stagnation. One of the case studies Christensen provides involves the manufacturers of the original floppy disk drives. There was a market leader for 14-inch disks, then 8-inch, then 5-inch, and then 3.5-inch. However, the market leaders were not the same across these size categories. Each time, it was a competitor that came in to take over the next evolution.

The reason each of these manufacturers lost its advantage was because it focused too much on improving its current product, and not enough on moving to the next big one. Ironically, the market leader of the new technology often had developed but failed to implement the next-generation disk. So while Memorex actually led the charge for designing 8-inch disks, it was Seagate Technology that pioneered that market. Memorex had a split loyalty between the successful 14-inch drive and the new—and at that time only potentially successful—8-inch disks. As a result, Memorex spent more time investing in the 14-inch drives and less on moving to the next big thing, in this case the smaller 8-inch disk.

This same concept applies to your career. Do not allow something in which you have had considerable success prevent you from finding your next big thing. Others will be quick to realize that change is needed and will accelerate away from you if you do not do so first. Consider a point made by Malcolm Gladwell in his book The Tipping Point, in which he uses diffusion research to explain how new products are brought into and become successful in the market. When something is introduced into the market, not everyone purchases it at the same time. For example, when televisions first appeared some people ran out to buy one, while others waited decades to purchase one (or perhaps never did). When exploring diffusion in terms of the way innovations and products are adopted, it becomes clear that two of the most critical roles are filled by those individuals in the groups known as Innovators and Mavens. These are the people who see a movement and embrace it before everyone else. They are the early adopters of products and technology. Similarly, they are also the early identifiers and adopters of new skills.

In your career you should aspire to be an Innovator or Maven in your pursuit to be among the first to find critical new skills that you must develop. Doing so will provide you with a great differentiator at work. If you wait longer you will become a member of one of the other groups described by Gladwell (Early Majority, Late Majority, and Laggards), at which point you will simply be playing catch-up with the leaders. Typically each group serves as a reference point for the subsequent groups to watch and learn from. When you are an Innovator in acquiring new skills to attain greater success at work, other people will watch and learn from you. And because they are learning from you it means you will keep an advantage in maintaining your trajectory.

A $100-BILLION LOSS

If we return for a moment to the DJIA, a further analysis of the companies that have been removed or added to the index will show you just how quickly a trajectory can change. As an example, let's take a quick look at Eastman Kodak. Eastman Kodak was added to the DJIA in 1930 and remained as part of the index for seventy-four years. In 2004 it was dropped and replaced by American Insurance Group (AIG). Eastman Kodak, of course, was one of the world's most recognizable brands, but still lost its way and had to be substituted. Fast-forward and AIG also lost its edge. Just four years after AIG was added it was replaced by Kraft Foods! Think about this. AIG was viewed by experts as such a strong company that it was chosen to replace Eastman Kodak and yet only four years later it was removed.

The decision to drop a company is not taken lightly, nor is the selection of the new company. That is why it is amazing to watch how quickly fortunes can change if you are not careful. When it was added to the DJIA in 2004 AIG had stated a net income of over $11 billion (this was later revised downward by over $1 billion). When it was removed in 2008 losses of nearly $100 billion were reported, a difference of $110 billion from 2004! AIG had made some very bad investment decisions that resulted in a negative financial impact to many people. Ultimately AIG was given a second chance to survive thanks to a government bailout to the tune of $182 billion. Fast-forward to 2011, and AIG reported a profit of $16 billion. AIG was eventually able to recover through a series of prudent decisions, including refocusing on its core insurance business. The company was willing to ask for and accept help and, critically, learn from its mistakes and admit where it was wrong.

From the mistakes of AIG you can pull important lessons for your own career. While recovery from mistakes is possible, you may have a long road to climb back depending on the egregiousness of the error. AIG managed to quickly find financial recovery, but even now has not fully reclaimed the positive reputation it once had. AIG thought it was wisely making money from a series of derivative contracts that were tied to mortgages. However, once the housing market burst AIG no longer had the liquidity necessary to cover payment to creditors. One such major mistake can result in an unwinding. Be careful that you do not become so blindly confident in yourself that you play it too loose and make grave errors. You should remain confident, but do not act like AIG and use your confidence and past success to create the false assumption that you are incapable of making a mistake.

If you react quickly and swiftly you can undo major mistakes before stagnation takes over. I think of Jessica, who was not performing very well in her job. Her supervisor knew that she had greater potential and had a conversation with her about how she could improve her performance. When she still did not improve she was placed on a performance improvement plan (PIP). With a PIP an employee is usually given a certain amount of time to improve performance. If there is no improvement more severe consequences can occur, including termination.

When she received the PIP Jessica had an eye-opening moment. It was at this point that she realized her trajectory was at risk and that she must take immediate steps to improve. Over the next few months Jessica focused intensely on the improvement needs outlined in the PIP. She refreshed and expanded her knowledge in areas critical to her job and began to perform better using this new knowledge. Ultimately she was taken off of the PIP thanks to her improved performance. Jessica's story gets even better. Just a little more than a year later, she was actually promoted and took on a new job with greater responsibility. Jessica's example underscores the importance of acting before it is too late. Had she waited any longer to adjust she likely would have fully stagnated and potentially even lost her job.

Finally, seeking help is usually wise and is not construed as a sign of weakness. You will not need to seek a massive financial bailout like AIG, but you can look to others for advice and guidance. When you reach out for development you put yourself in a position to be able to advance in areas in which you could otherwise become stagnant. As you have already learned, this is increasingly important in the modern workforce, where skills become stagnant faster than ever because of rapidly changing technological advancements.

Conditions and skills necessary to succeed are changing faster now than at any point in modern human history. How many times have you heard people talk about “the good old days” with fondness? How many times have you talked about them yourself? The good old days are normally in reference to a time several decades ago, a time that was easier. But the world changes much quicker now. In fact, the good old days might be only five years ago, or even less. We talk of a time before cell phones. We can't imagine life without the Internet. Or without Google. Or GPS in our cars. The world is now evolving so quickly that you must be an expert at adaptation and reinvention. You must be able to change what you do and how you do it. This does not imply that you need to change who you are. Instead, you must change your skill sets and think ahead. If you do not adapt quickly you will become stagnant or, worse, irrelevant. Not adapting quickly is particularly dangerous in both large and fast-moving companies. In those types of situations others will view you as an obstacle to progress and will begin to find ways to work around you instead of with you.

I am reminded of a colleague who saw industry changes happening and took extra initiative to avoid stagnation. Bill had been on an analytics team for more than ten years and was considered the go-to person when it came to handling large sets of data. He knew all of the shortcuts in Microsoft Excel and was able to work with the data more quickly than were his peers. The amount of data his organization collected was increasing exponentially, and Bill realized he would no longer be able to keep up with the data needs of the company using his old approach with Excel. Bill knew that he needed to expand his skill set so that he could better manage the “Big Data” that corporations are scrambling to manage and better understand. In doing so he exhibited the characteristics of a Maven.

As soon as he recognized this need, Bill reached out to his boss to express his interest in learning more about this area. His boss realized how this could be beneficial and agreed to send Bill to an upcoming conference on the topic, and also to fund tuition for a night class on analytics. Not only did this enable Bill to learn more to avoid stagnating, but he also was considerably more engaged in his job because of his excitement with the topic and the support that his boss provided. Moreover, he was able to quickly apply his new education to the job and further increase his contribution to the organization. Bill is a wonderful example of how not to drift into stagnation. He recognized an opportunity and reacted quickly. Had he waited it would have been more difficult and time consuming for him to catch up and acquire the new skills.

HALTING STAGNATION

Stagnation can occur at any point in your career or life. Stagnation can take the form of being risk averse, and it often begins with a setback. Other times it occurs as a result of not paying attention to what is in front of you, to what others are doing. This is not insurmountable, and the true measure is how you react to the setback.

The Olympic gold medalist and National Hockey League Hall of Famer Mario Lemieux—who played for the Pittsburgh Penguins—is a great example. During his career he had problems with his back, which resulted in his missing more than 100 games during the first nine years of his career. But then he was dealt an even bigger career setback when he was diagnosed with cancer early in 1993. A month later he began a series of twenty-two radiation treatments. What is truly amazing is what he did right after his final treatment: He not only boarded a plane to rejoin the team but also actually played in the game that night. While many were surprised, others felt that this was Lemieux's plan all along. He had prepared every day during his treatment with the intent to return as quickly as possible. As Lemieux stated, during his radiation treatments he was always thinking positively about not just returning to the NHL but also regaining the NHL scoring title. This strong self-confidence enabled him to think ahead and to avoid the negativity and doubt that can all too easily turn into stagnation.

Lemieux provides us with an incredible illustration of choosing one's own trajectory. When diagnosed with cancer, he did not stagnate and let his trajectory point down. He could have used his illness as a reason to stop training. He already was one of the most accomplished players in league history, and no one would have questioned him had he decided to retire. Everyone would have understood. But no, Lemieux decided that he was going to push past the cancer. Not only did he do that, he again became the NHL scoring champion, just as he told himself he would when he was diagnosed.

One of the hardest things you need to do to avoid stagnation is to change your approach when necessary before you fall into a rut. This of course requires you to recognize that something that once worked no longer does, which unfortunately does not always happen easily or right away. People instead often exert even more effort in an attempt to obtain the same outcome as before. However, the desired outcome will never occur in the intended manner once conditions have changed. What was rewarded in the past may no longer work or be valued. Instead of quickly changing the behavior, people do more of it. Remember Ron, who as you learned in “Getting Started” suffered under the changing conditions after he was hired? He entrenched himself in his comfort zone and refused to let go of his old ways.

We can draw upon psychological research to help explain why we continue to act in the same way even though we know conditions have changed. By better understanding this tendency you will be able to recognize its onset, which will in turn put you in a position to better avoid this type of unproductive behavior.

In reinforcement theory there is a phenomenon known as an extinction burst. When an extinction burst occurs a person repeatedly tries, unsuccessfully, to do something that worked previously. Think, for instance, about a soda vending machine. You expect it to work and are trained to anticipate the same outcome each time. Simply put in a few quarters, push a button, and a drink comes out. Have you ever watched what people do when it doesn't work? They will look at the machine for a moment, mystified, then push the button again. Nothing. Then they push it again, and then even faster. Still nothing. And they push it again. You get the idea. They repeat the same behavior several times before accepting that the expected outcome is not going to happen. Another easy way to illustrate an extinction burst is with gamblers. Instead of recognizing a loss and walking away, they opt to bet even more in hope of making a bigger gain to recoup their losses.

The same concept applies to your success and even to the success of entire organizations. At work it would be easy for you to repeat the same behavior, just as you would with an extinction burst, because that was what enabled you to be successful in the past. You cannot allow yourself to fall into this trap. There is a quick learning curve with a vending machine, and most people will give up fairly quickly. In your job, however, it will not be as easy to determine that something that once worked is no longer working. Unlike your reaction to a malfunctioning vending machine it may be hard for you to admit that something you once did well may not work in the future. This is especially true when what isn't working is in an area in which you are particularly strong or have received accolades in the past. Don't make this mistake. Do not ever become complacent with the development of your brand and skills. Do not double down, as the losing gambler would, and do more of the same. Instead, redirect your energy and exert those efforts toward doing your next great thing.

THE STAGNATION OF YAHOO!

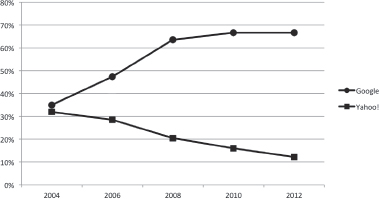

In the earlier days of the Internet, before Google (BG), people used Yahoo! as their go-to search engine. It was by many accounts the preeminent site on the Internet. By 2012, however, Google—which did not even exist until 1998—had attained a search engine market share of more than 66 percent. To truly understand how significant this is, you need to go back only ten years. In 2004, Yahoo! and Google were essentially tied in online search, with both claiming nearly a 30 percent market share. As you can see in Figure 5-3, the companies have been on different paths ever since. Whereas Yahoo! allowed itself to stagnate, Google kept its appetite for innovation and growth and constantly looked to expand its capabilities and offerings.

Google Maps, Google Earth, Google Images, Google Scholar, and Google Shopping are all examples of a series of user-friendly web services the company developed. The purpose of each of these is to draw users to Google, thereby increasing user traffic and subsequently the opportunity for advertising revenue. Ironically, while doing research for this section of the book I used Google to search for background information about Yahoo!

Figure 5-3: Search Engine Market Share

Examining Figure 5-3 shows you how stagnation can quickly lead to a downward trajectory. From a point of parity in 2004, Google pulled away at an accelerating pace. Yahoo!'s loss literally became Google's gain. If Yahoo! had simply reached a plateau, the company would have maintained its market share of 30 percent. That would not have been entirely bad, especially when put against the comparably small 12 percent market share it had fallen to by 2012. The graph underscores how quickly stagnation can lead to a rapid decline. As with Yahoo!, your decline can be someone else's gain. In this case, Google took advantage of Yahoo!'s complacency and propelled itself into a position as the clear leader. Don't let this kind of situation occur in your career. Always keep in mind that it is important to reinvent your skills and knowledge base. If you don't, you will only be playing catch-up.

You will encounter challenges similar to Yahoo!'s throughout your career. Whether you are at a point of equivalence with others or are much further ahead, constantly maintain vigilance for the next competitor that, like Google, is ready to take your career market share. Career development and growth is constantly ranked in surveys as the most important factor at work for employees—even higher than pay—and you need continual development and growth to avoid stagnation. If you do not do this, you risk ramifications beyond just losing ground against others and stalling your career. An absence of career development can lead to stress and feelings of anxiety, and eventually you may even begin to dread going to work.

CONCLUSION

In many areas of your career a quick recovery from mistakes is possible. For instance, you could go a month or two without receiving feedback (Lesson 1) and you probably would not have done something so drastic that you would be derailed for a long period of time. If you find yourself in the throes of stagnation, however, you will likely have a difficult time digging yourself out. Once you let stagnation set in, the consequences are far reaching and hard to undo. For this reason you must constantly self-assess your skills and progress against your trajectory to keep stagnation from taking hold.

Be out at the front of positive change, and be an advocate of it. You cannot passively sit on the sidelines and wait for change to come to you. Sometimes you will need to go against what feels natural and comfortable. Memorex found comfort in knowing it had success with 14-inch disks. Even though the company knew that the future was moving toward smaller disks—and had built the technology for it—it was slow to break out of its mold and go “all in” on the future. If you are always just putting your toes in the water, you will never be able to go all in with your own career and aspirations.

EXERCISE

Identify a skill that is critical for your job and is one that you feel is a personal strength. This should be the skill that differentiates you the most from others. Think back to when you first started your job and how accomplished you were with this skill at that time. Does this skill matter as much now as it did then? Do you still have the same competitive advantage with this skill when compared to your peers? If not, what do you need to do in order to get the advantage back? Write down your answers on the Notes page and then list any new skills that you need to acquire in order to immediately develop and grow.

NOTES