LESSON 4

BREAKING THROUGH PLATEAUS

Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or present are certain to miss the future.

—JOHN F. KENNEDY

In your life and career you should remain conscious of the fact that the bend in the road does not have to be the end of the road. As you seek to progress you will place yourself at a point at which you can see past the bends in the road along your journey and will be in a better position to successfully manage your trajectory. If you do not position yourself this way, you may have found your resting place, your plateau—the point at which your trajectory is no longer continuing upward in the traditional sense. As you will learn, the acceptability of this is a matter of perspective based on where you are currently in relation to your aspirations and goals.

It is at these plateau periods, which often are preceded by a period of success, when you will need to rapidly seek out new ideas and approaches. It is critically important to be aware of the possible dangers of a plateau in advance, as once you reach a plateau you will have lost considerable time and it will become harder to continue advancing at the same pace. In other words, you run the risk of experiencing a flat trajectory for a much longer period of time—or worse, becoming stagnant. Just as critically, others who have adapted and changed faster may already have solidified their position at the next step you had aimed for in your trajectory. In that case it will become even harder for you to break out of your plateau.

STAVING OFF A PLATEAU AT IBM

At some point along every continuum of success a plateau begins to appear. It is the natural evolution of any life cycle. When you accept that this will happen you will be better able to prepare for it. Thus, before reaching a plateau you must proactively plan for innovative and new ways of doing things. Without this, future growth becomes stalled. Consider IBM, which is one of the most successful and admired companies in the world. In 2012 IBM had revenue in excess of $104 billion and its profits approached $18 billion. But it wasn't always this way.

IBM was a dominant player in the computer server and PC space, but its fortunes began to change in the late 1980s. Part of the issue was that more than 90 percent of its profits came from its server business. IBM had become a one-trick pony and was not adequately prepared for a changing market. It had reached a plateau, which almost turned into a sustained failure. Consider this amount: $13.1 billion. That is how much money IBM lost in just two years!

Based on the many issues and risks facing the company, the IBM board of directors decided that changes were needed. What resulted was a change at the top and the surprise selection of Louis Gerstner Jr. as the new CEO. Not only was he an outsider to IBM, he also was not experienced in the technology sector. His appointment presented a daunting challenge, particularly because a number of analysts and many in the press vocally questioned his readiness or capability to fill the role.

One of the biggest problems Gerstner found at IBM was a culture of self-contentment and complacency. The attitude seemed to be that because IBM had been so successful in the past, it surely would remain that way. The company felt it could continue to ride a wave based on past success, when in reality the wave had washed ashore and IBM was left at a plateau. Even worse, it was a plateau that was beginning to turn downward toward stagnation. It would have been easy for Gerstner and his team to continue along the current path. Instead, Gerstner chose to do something different. He realized he had a choice: He could reach to break IBM out of the plateau, or continue to do much of the same and embark on a further downward spiral that might not stop.

He chose a bold course, which ultimately proved to transform the future of IBM. As Gerstner remarked, the actions the company would take would determine whether “IBM was merely going to be one more pleasant, safe, comfortable—but fairly innocuous—participant in the information technology industry, or whether we were once again going to be a company that mattered.” In other words, he knew that IBM could remain on a possibly comfortable but irrelevant plateau, or do something drastically different and again become a leader in the field.

The first thing he did—and likely the most important—was to reverse course from the direction his predecessor had set. The prior CEO, John Akers, had secured support to break up IBM into multiple independent business units with the idea of enabling a structure that would allow decentralized market-driven decisions. Gerstner looked into the future and saw something different. He saw a market in which consumers wanted end-to-end solutions. He stated that he thought what consumers really wanted were comprehensive solutions with continued support. Working from that belief, he made a strategic decision to focus on which business units to keep and then to operate them as one company. He also bet big on the services sector, which grew exponentially to become a $30 billion part of IBM's business under his watch.

It is worth noting that Gerstner was well versed in the principles we reviewed in Lesson 1. As an outsider with a non-technology background, he knew that many answers and ideas would come from others. He spent considerable time seeking out opinions both inside and outside of IBM. He gathered feedback. The changes that Gerstner and IBM instituted were dramatic, but so were the subsequent accomplishments. Gerstner's actions were aligned with an old saying about wild ducks that the company had long used to express an important part of its culture. The idea behind it is that you can make wild ducks tame, but you cannot make tame ducks wild. In other words, once tamed, the ducks lose motivation and the desire to explore new things. Applied to work, it means that IBM realized it must give people room to do new and creative things. Not doing so would result in complacency and plateaus. As a testament to how much innovation has resulted from this philosophy, year-over-year IBM routinely receives more annual patents than does any other company.

INFLECTION POINTS

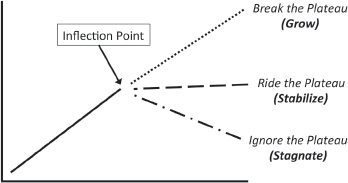

Along your career trajectory you will have moments at which you are approaching or are already at a critical juncture. Ideally it will be the former and you will notice it coming, which will provide you with more time to react and plan. Everybody has or will have one or more of these times during their career. Andy Grove from Intel, whose own critical moment we covered in Lesson 3, refers to these as career inflection points. It is very possible that had Grove made the wrong decision at his inflection point he would have had a much less illustrious career. In Figure 4-1 you can see that there are three different paths you can take leading out of a career inflection point. What's more, this will likely be a career-defining choice that you must make. Your decision can be distilled down to three options: you can decide to do something drastically different and break the plateau (grow), appreciate and ride the plateau (stabilize), or remain in denial and ignore the plateau (stagnate).

Figure 4-1: Career Inflection Point

The top line represents what can happen if you embrace the opportunity and decide that it is time to enact radical change and do something that will set you apart. You use it as a time to grow. This growth could be in the form of self-improvement or developing new skills. It might involve searching for a new job, or perhaps even doing something entirely different.

The middle line indicates staying on the plateau. If this is the option you choose, you must go through a period of introspection and be clear on several points. First, if you continue doing what you are doing, will it be sustainable? Oftentimes it will not be and you could find yourself in the uncomfortable position of no longer adding value. If it will be sustainable, you then must decide whether you feel that you will remain content continuing to do what you are doing now. For some people, this will be just fine. However, because you are reading this book, it is unlikely that you will give serious consideration to any path other than growth.

It is essential during a plateau—a period of stabilization—to ensure that you do not let your trajectory begin to gradually point downward. When you become entrenched in one thing, you will over time lose the ability to innovate and progress. This will harm your trajectory. Life changes, markets change, and so too can your goals. It is up to you to chart your course, and that course can differ over time. Again, the important thing is to keep it from pointing down for too long.

In the next sections we will discuss the experiences of people who followed each of the first two paths shown in Figure 4-1, and reveal what happened as a result. The bottom line in the figure—the only line that points downward—is what happens when you remain in denial and refuse to accept the reality of a changed situation or choose to ignore it. In Lesson 5 we will cover this option, also known as stagnation, in more detail.

BREAK THE PLATEAU (GROW)

In 2008, at the age of fifty-nine, Joe Moglia announced his retirement as the CEO of TD Ameritrade after a very distinguished career. At that point he went on to do something radically different from what was expected for someone of his stature. When you trace Moglia's career trajectory it is easy to understand why so many people were shocked by what he did next.

By the young age of thirty-three, Moglia had established himself as the successful defensive coordinator of Dartmouth's football team—so successful that the team had won consecutive Ivy League titles the two prior seasons. And yet he had decided he was going to walk away. He seemingly gave up his dream of becoming the head coach of a Division I college football team and instead took an entry-level job at Merrill Lynch. Though it was not easy for him to leave coaching, he did so in order to be able to provide better financial footing for his family. He spent the next seventeen years at Merrill Lynch, and during that time rose through the ranks to a top executive role. When he left in 2001 it was to take the top post at TD Ameritrade. What followed under his leadership there was a remarkable turnaround of the then troubled company. In his seven years as CEO, TD Ameritrade grew from approximately $24 billion to $300 billion in assets managed—more than a twelve-fold increase!

When Moglia walked away from TD Ameritrade he embarked on a new path in his trajectory and showed amazing persistence along the way. His new path was actually back on his original trajectory. He had always dreamed of being the head coach of a Division I college football team and wanted to try again. To do so required financial sacrifice, and he went from being a CEO making millions of dollars a year to taking on a job as an unpaid “intern” with the University of Nebraska Cornhuskers. During his two years with the Cornhuskers he put in the same extreme hours as the paid coaches so that he could get back up to speed with the game he had left behind so long ago. He did so because he felt that this was the right strategic move in his trajectory and that it would lead toward a head coaching job at a Division I college. In 2011, at the age of 62, he took yet another step closer to that goal when he became a head coach for the first time with the Omaha Nighthawks of the United Football League (UFL).

After his one season in the UFL, Moglia applied for head coaching jobs at Division I schools. Finally he reached the point that he had always wanted in his trajectory; when he became the head coach of the Coastal Carolina University Chanticleers. Not only did he reach the target of his trajectory, he did something else: In his first year as coach the team won the conference championship and he was named the conference's coach of the year.

Moglia undoubtedly did not take the decision to leave TD Ameritrade lightly. It's hard enough to walk away from a job and career, let alone one that you are leading and in which you are financially secure. But he was at a good spot and likely saw that a plateau in his current role was approaching. It would be a place where he could do more, but his trajectory would not be as steep. Or as fulfilling.

Not everyone will need to go to the same extreme as Moglia to break out of a plateau, but it is important to be open to other opportunities and ways of doing things. One of the great things about your trajectory is that it is yours. Even if you go down one path, it is never too late to go down another. Perhaps no one exemplifies this better than Nola Ochs, who at the age of ninety-five became the oldest person ever to receive a bachelor's degree. Not satisfied with stopping there, Ochs continued on and received her master's degree just three years later, in 2010. Changing course can be hard when everything is going well, but as Nola Ochs demonstrates, you can do it. Keep your eyes open and always be ready.

RIDE THE PLATEAU (STABILIZE)

Staying at a plateau does not have to be a bad thing. However, if you decide to remain at a plateau, you do need to accept and be content with your decision. What is critical for you to not only understand but to know about yourself is that your goals and aspirations will determine how you view a plateau. This is where positive and negative plateaus come into play. There could be times in your career when reaching a plateau is quite desirable. In fact, you may even reach a point at which a permanent plateau is desirable.

Consider Qiang, who was a successful lawyer at a Fortune 1000 company. Qiang had advanced rapidly up the hierarchy and had attained a senior-level position in the legal department at a relatively young age. Doing so required him to work long hours and travel excessively. Due to his success he was offered several more promotions, each of which he turned down. This befuddled his hard-charging bosses, who could not understand why this once promising attorney was no longer interested in greater impact, pay, and visibility.

I had worked with Qiang on several occasions, and when I asked him about this he stated that it was quite simple. He had sacrificed a great deal early in his career while he sought to advance and reach the role he had always desired. Once he did he found that he was no longer interested in continuing to advance upward in the organization. He had reached a position where he really enjoyed what he was doing with the specialty area of law that he was practicing. What he realized is that he was comfortable with reaching what became a permanent plateau.

Because Qiang decided that a permanent plateau was acceptable, this became a positive plateau in his mind. Instead of this being a negative, he found it appealing and fulfilling. Had he wanted to advance further but been unable to do so, he would have instead experienced a negative plateau. With a negative plateau you will not find comfort or satisfaction. You will instead feel that you are stifled and no longer progressing.

Or consider Claudia, who after several promotions had become a general manager. After about a year in this role, she was approached about a new assignment leading the opening of a new location, with the opportunity to then progress into a market-based role with responsibility for multiple locations. While Claudia was grateful for the support and recognition, she indicated that she was not interested in changing jobs. Like Qiang's, her reasons were rather simple. In addition to being fulfilled in her role, she knew that her family had really grown attached to the area where they were living and their local community. She did not want to have to face multiple moves that would require uprooting her family and the ties they had established. Claudia really liked her team and made an internal commitment that her goal would be to continue to grow and to make her location the best and most successful in the company. It's hard to have an issue with that type of attitude and commitment. Claudia is another example of someone who found her own positive plateau.

I want to be clear that a positive plateau does not mean that you can rest on your laurels. You still will need to evolve and keep up with the change of pace for your role. Being comfortable at a plateau does not suggest that you can stop developing, learning, or performing. If you let that happen, what was once a positive plateau will quickly turn negative.

STABILIZATION AND FLOW

Since a plateau can be desirable at some points in your career, we should also recognize key career benefits that can be garnered during this time. A plateau can afford you a time of stability and an opportunity for deep learning. This stable period may even seem like a resting point in your career, because you are well-versed enough with what you are doing that it seems like you are putting in less effort than you had to in the past. However, in almost all situations achieving this level of competence does not mean that you have fully mastered something. There is always more to learn.

It is important for you to realize that you are approaching or are at a plateau, and then decide what you want to do about it. Like Qiang and Claudia, you may reach a point at which you very much enjoy what you are doing and want to continue doing that for the indefinite future. There is nothing wrong with this. However, if you want to move on to something different or bigger you will need to quickly chart a course away from the plateau. If you spend too much time on a plateau you will move from a period of stability to a time of stagnation, which occurs when you lose ground against others in relation to your planned trajectory. As you will learn in Lesson 5, this can be caused by several factors, including not building new skills, not innovating, or becoming complacent.

Realizing the importance of not becoming complacent, a positive aspect of spending a stabilizing period of time in a plateau is that it can afford you the opportunity to reach a state of mastery over a given area. In what Mihály Csíkszentmihályi calls flow, you become so proficient at something that you reach a point at which you feel complete mastery over what you are doing and develop a strong sense of control and self-confidence. Something that was once difficult for you may seem to become effortless. Or you may be so stimulated by an activity—even if you have not mastered it—that you lose track of time.

Have you ever found yourself in just such a state of concentration and engagement with an activity at work? Has this happened to the point that you lost track of the time? Perhaps it resulted in your missing lunch, or being late for a meeting. If so, you likely were in a state of flow. And it is also likely that you were engaged in an activity that met three primary conditions: you enjoyed it, it required concentration, and you had the capability to do it.

The conditions for flow are maximized when a task is not simple and when a person has considerable skill and interest in the activity. Csíkszentmihályi uses the example of surgeons as having a job that's prime for flow. Not only do successful surgeons have great passion in their job, but the conditions required to start flow (high level of concentration, no distractions in operating room, etc.) are optimal. In an experiment in which he monitored how often workers experienced flow, Csíkszentmihályi found that higher frequency of flow was associated with higher satisfaction on the job. If you never experience flow at work and are constantly watching the clock and waiting to go home, you have not found a job you enjoy. This is an indicator that you need to begin looking for a new step in your trajectory.

Flow does not occur when you are disengaged in an activity, nor when you lack the skill to do it. Skill in any activity is something that can be developed and mastered over time, but you must have the baseline capability for it. It requires excessive practice. However, it cannot be just any type of practice; it must be deliberate and focused. If you want to learn to play the piano, practice will be much more powerful if you turn off the television and remove yourself from all distractions. It will be even better if you have clear goals and a plan for practice that you follow. Add to that getting immediate feedback on your performance, and your practice will have even more positive effects.

Research by K. Anders Ericsson and colleagues has shown that to truly master an activity a minimum of ten years of focused practice is needed. This has been popularized as the 10,000-hour rule, which is based on the approximate amount of practice that experts in a given field put in during those ten years that separates them from others. At work, if you are constantly moving from one role to another, you are learning rapidly but are not affording yourself the time for deep learning. A plateau can provide you with a time to conduct this deliberate practice. Of course, by the time you are at a plateau you will have spent much time learning already. Consequently you have likely amassed years of “practice” in your area of expertise. Ericsson goes back to research from 1897 by William Bryan and Noble Harter, who recognized this when looking at plateaus in the skill acquisition capabilities of Morse code operators. The researchers found that when the operators were at a plateau (i.e., their skills were no longer improving naturally), the plateau could be broken by putting those workers through deliberate and focused training.

If you recall persistence and intrinsic motivation from Lesson 2, you will realize that these are two of the key factors that can result in reaching a state of flow at work. It is hard to put in deliberate practice without persistence, and it is equally difficult to persist if you are not motivated in your area of work. When you have these two qualities, though, you will be able to increase your skills to find that state of flow. You could even begin to feel like you have the “Midas Touch” and that everything you do will seemingly turn to gold.

Finally, during a period of stabilization you can build up the skills to not only improve in your current role, but to prepare for your next one. In many ways you are expanding the skills that will make your transition to the next step easier. This will leave you with more energy and optimism as you approach your next challenge.

LOOK PAST SUCCESS TO NEW INNOVATION

It is important to not fixate only on that which has made you successful. While you do not want to forget your successes, dwelling on them for too long can become problematic. Doing so will close your eyes to transcendent trends that could turn into permanent game changers. If you catch these early you may be able to propel yourself forward. Missing them, however, could lead to a downward trajectory and prevent you from developing new or innovative skills, approaches, or products on your own. When you focus only on your success, it becomes easy to miss what is happening around you. Then, once you do realize what is happening, you will already be at a plateau.

Consider the news on June 29, 2012, when CNN and Forbes ran very different, yet inextricably related stories. Forbes was covering a major milestone in the life of Apple; CNN was reviewing how far a once booming company had fallen in recent years. Forbes was covering the five-year anniversary of the iPhone and celebrating its tremendous success, whereas CNN was discussing the amazing decline of RIM, the maker of the once omnipotent BlackBerry phone.

The success of the iPhone was directly related to the near-complete collapse of RIM. The main differentiator? Innovation. Steve Jobs and Apple never stopped innovating. RIM, however, could never get past the success of the BlackBerry. Though that phone was once an amazing device—and had a nearly complete hold on the important corporate market—RIM was late to the game in adapting. It did not see what was happening around it in the market and so did not make the necessary course corrections. It had become complacent based on its past success and drifted quickly into a plateau. Any changes it did make were minor and did not substantively break the mold from the products it had made in the past. Conversely, Apple continued to release new products and enjoyed a steady rise because of its continual innovation of products.

A. G. Lafley once stated, “The best way to win in this world is through innovation.” As the CEO of Procter & Gamble he realized the importance of this and refers to innovation as the game changer. He notes, however, that innovation by itself is not sufficient. You also need to execute against your goals and priorities. Without doing so, innovation can be rendered nearly meaningless. Even all of the innovation by Apple would be to no avail if the company could not also build and deliver the products on time.

Like Lafley and so many others, you should consider innovation as one of the most important devices you have at your disposal to get past a plateau. You must constantly be looking for ways to innovate and seek out novel solutions both to problems and opportunities. Keep in mind that novel does not need to mean difficult solutions. Nor does innovate need to mean new. That is one of the great things about so many innovative solutions: more times than not you already have the answer. You just need to release your mental holds and identify what is often right in front of you. The smartphone was not invented by Apple; there were many models already in the market when the company released the iPhone. Apple simply innovated by taking something already in existence and creating an intuitive design with features and capabilities that surpassed anything else available.

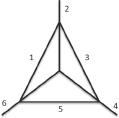

In his classic book On Problem Solving, the late German psychologist Karl Duncker described a series of experiments he conducted to assess barriers that keep people from finding the right solution to a given problem. For example, participants were given six matchsticks and asked to find a way to create four equilateral triangles. Blinded by standard ways of thinking, few participants could find the correct solution, which is actually rather straightforward. Go ahead and see if you can figure this out. If you are stuck, see the solution on page 126.

In a much more commonly referenced problem, Duncker gave people three small boxes: one with matches, one with three candles, and a third filled with tacks (the experiments used multiple variations, including giving the matches and candles without a box, and filling the boxes with material—such as buttons—that were irrelevant to the solution). The instructions were quite simple—participants were asked to find a way to affix the candles to the wall and to ensure that no wax would drip onto the floor once lit. This is an example of a situation in which the answer was right in front of them, yet many failed to see it. They saw the boxes as holders of the various pieces of the puzzle, but not as part of it.

In fact, the best solution is to empty the boxes and then affix each to the wall with tacks, with the opening of the box facing upward. After doing so the candles could be placed in the boxes and lit. People in the experiment were confined by what Duncker termed functional fixedness. More simply put, it was constrained thinking that prevented people from solving the problem. When this occurs, you see something only for what it is, and miss seeing what it could be. In this case, many participants saw a matchbox, a tack box, and a box of candles, and failed to see that the boxes could actually be repurposed as candleholders.

On an organizational level, W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne explored innovation through evaluating companies that pursued what the authors termed a red ocean or blue ocean strategy. With a red ocean approach you are trying to compete in an existing area, one where the competition is known. In contrast, with a blue ocean approach you are diving into unknown areas where the market space is not known. While it is important to be aware of the red oceans, by charting into blue oceans you can really innovate and differentiate yourself.

In many ways a red ocean approach is defensive, whereas a blue ocean strategy is proactive. The reason for terming this scenario red ocean is that the waters become bloody because of the cutthroat nature of those who are competing against you. By moving into blue oceans you can focus more on yourself and what you feel you need to do in order to innovate and succeed. You consequently create an internal competition, which results in a more fulfilling and positive outcome that does not involve cutting others down.

BE A BEST PRACTICE

Organizations are constantly searching for best practices they can adopt to gain an edge. Doing this too much, however, can create a problem. A best practice is learned from those who are already ahead. You are just playing catch-up. By simply adopting a best practice you can only get yourself to a point of parity. To really excel you need to refine and create best practices. When you do so you can utilize these skills before the best practice has become a common practice. You want your brand and skills to be at a point where others seek you out to learn from you. When you reach that level you can serve as a mentor to help others, which as you learned in Lesson 1 can be of great value. When you are not able to stay ahead in this manner you increase your risk of stalling at a plateau.

When Henry Ford forever changed the way we travel, he was thinking ahead. Sam Walton did the same when he realized that he could shave costs through building and managing the best logistics network in the world. Steve Jobs did it when he revolutionized the tablet computer. Bill Walsh did it when his West Coast Offense transformed the passing game in professional football. Each of these individuals looked for opportunities and capitalized on them, creating best practices that were emulated by other people and organizations. To do the same in your career you must be willing and able to put in the effort to change faster than others. Consider the fact that it is much harder to notice yourself aging than it is to notice how much a friend whom you have not seen in a long time has aged. That is because it is harder to see what is slowly changing in front of you. Now place this against the context of your workplace. If that is all you know and pay attention to, you may not notice how quickly things outside of it are changing.

CONCLUSION

What is unique about plateaus is that your individual circumstances determine how you should view one at any given time. Plateaus are not always bad, nor are they always good. A plateau is situational. What may be a negative plateau to one person is a positive plateau or ideal state for another. Qiang and Claudia were talented employees with great capabilities and chances for further upward promotion, but for their own reasons each decided to turn down desirable career opportunities. The primary reason was that they both truly enjoyed what they were doing.

When you do take a step forward in your trajectory, do not allow yourself to bask in the moment for too long. The skills that got you there are not always the skills that will keep you there. If you rest, you will plateau. In sports we often hear of athletes whose production falls after they receive a big contract. They just spent several years building a successful track record of performance to warrant the new contract. All too often they bask in that success and do not continue to reach for greater things. They may continue to perform well, but they never take it to the next level—the level that was expected of them.

Plateaus may provide a point of reflection. Maybe it is time for you to consider moving toward something else. You may want to explore a new trajectory that perhaps you had not thought of before or, as Moglia did, reconsider a once desired trajectory that you had given up on or left long ago. If you are reading this and are frustrated with where you are now, consider whether it is where you thought you would be and if it is what you want to be doing. If not, was there something else that you were once passionate about to which you could return?

Ultimately you must decide which path to take if you reach a plateau. It will probably be one of the two discussed in this lesson. The right choice will be the one that provides you with the most enjoyment and fulfillment at work and in life.

On the next page is another exercise for you to complete before we turn to Lesson 5, which covers the third option coming out of a plateau: stagnation.

Solution to Karl Duncker's puzzle: In order to create four equilateral triangles you must create a three-dimensional figure with the matchsticks. Most people do not change their thinking and continue to try two-dimensional approaches to solve this problem.

Figure reprinted with permission of APA from Karl Duncker, “On Problem Solving,” trans. Lynne S. Lees, Psychological Monographs 58:26 (1945), published by APA.

EXERCISE

Each of the following two columns contains ten words. Take a moment to consider how you most often feel about your current job and where you are in your career. Circle the words in each column that describe how you frequently feel.

| Stuck | Happy |

| Limited | Fulfilled |

| Bored | Excited |

| Demotivated | Engaged |

| Angry | Challenged |

| Stretched | Motivated |

| Burned out | Eager |

| Frustrated | Relevant |

| Meaningless | Enthusiastic |

| Discouraged | Meaningful |

Now count up the total number of circles in each column. If you have one or two more circles in the first column than in the second you are likely approaching a plateau. If you have many more circles in the first column than you do in the second, you are likely at a negative plateau and you need to take quick action to break out of it. If you have more circles in the second column, you are at a good place and are not at an immediate risk for a negative plateau.

NOTES