Chapter 7

The architect's role within a construction project

This chapter:

- provides hints and tips for managing risks when pitching for work

- describes the different role specifications that an architect may agree

- provides an overview of the services expected to be provided by an architect during each RIBA stage.

7.1 The relationship between the architect and the client

7.1.1 The importance of the architect to the client

This is very often the key relationship on the project. Although for larger projects the situation may be more complex, and will vary depending on the procurement method and whether other consultants, such as a project manager, are involved, the architect’s role may be nothing short of advising the client at every stage from the first idea to the finished building, from vision to reality.

7.1.2 What should the architect look for in a client?

The decision-making process which an architect goes through when deciding whether or not to take on a client is covered in Stage 0 in the RIBA Job Book.

Every commercial relationship involves an element of risk, but developing an effective strategy for this stage will help you avoid taking on clients and projects that present serious foreseeable risks. One good approach is to create a ‘scorecard’ setting out a list of relevant questions that would need to be answered prior to involvement in any project. The answer to each question is given a rating, for example 1 to 5, with 1 representing a low risk and 5 a high risk – the importance of each answer will be specific to your business – and the final score will give an overall picture of whether the potential risk associated with the job or client is outweighed by the potential reward.

This kind of tick-box approach works best when combined with commonsense analysis of the results based on experience; over-reliance on a tick-box approach creates problems when the decision-makers stop thinking.

Many well-known and highly successful practices use scorecards, covering broadly strategic/practice management issues – the fit of a project with the firm’s business plan, the likelihood of obtaining repeat business – as well as issues that may have a direct impact on the potential scope of the firm’s legal liability. The weighting given to each answer will vary from practice to practice, as will the threshold that needs to be reached before a project becomes attractive; some architects are more risk averse than others. An example of a ‘legal’ scorecard is given opposite.

7.1.3 What does the client want from an architect?

The RIBA produces a number of guides and brochures, available free of charge, that aim to inform and manage the expectations of clients who may be considering consulting an architect. These range from ‘Working with an architect for your home’ for domestic clients through to ‘Commissioning architecture’, aimed at business and institutionl clients. Another detailed RIBA note called ‘It’s useful to know …’ provides detailed guidance to help clients understand the architect’s role in a building project. A Client’s Guide to Engaging an Architect (July 2016 edition) is available from the RIBA Bookshop and is perhaps the most thorough source of information for clients about the role of the architect, the process of design and construction, and the regulatory framework. Guides such as those produced by the RIBA, the marketing literature of individual practices and the preconceptions of clients themselves combine to shape a client’s expectations.

The RIBA material emphasises not merely ‘the value of an architect’ but encourages potential clients to view the engagement of an architect as a necessity. Clients are informed that all architects are trained to define the client’s objectives and develop designs that imaginatively interpret the client’s vision. Architects are trained to secure the approvals necessary to ensure that a project can go ahead, and to manage the construction phase, by helping the client to select the right procurement route, select a suitable contractor, obtain competitive prices, oversee co-ordination of design and integration of any subcontractor-designed elements, and monitor progress, quality and safety on site.

The guide ‘Commissioning architecture’ encourages sophisticated commercial clients to understand the value of consulting an architect in terms of time, money, utility and beauty:

Client expectations are high, and demands follow expectations.

It is important from the client’s perspective that they are properly protected in the event of a problem with the project. In terms of the potentially overlapping roles of their team of professional consultants, the client will want to be certain that the respective roles and responsibilities are well defined so that no individual task falls between the cracks. This can only be achieved if the schedules of services in each professional appointment have been thought through and drafted accurately, so that every service that needs to be performed in order to make the project work will be completed by one of the consultants.

7.2 The architect's services

7.2.1 Defining the architect's services

The schedule of services is the part of an architect’s appointment that sets out ‘what’ they will be doing; the terms and conditions of appointment set out the standard that the architect must achieve when performing the services.

The architect is obliged by the ARB Architects Code and the RIBA Professional Code of Conduct to have agreed a written appointment, setting out both the terms and conditions of appointment and their services, prior to providing any services.

It is in the interests of both the client and the architect that the client knows and understands what services the architect will be providing. If the architect’s schedule of services has not been drafted by the client, it must be fully explained to the client; failure by the client to properly understand the architect’s role and responsibilities during the design, planning and construction process is the root cause of many disputes and complaints against architects.

The RIBA stages are long established and firmly based in a logical order, and this logical ordering is evident in the RIBA Plan of Work 2013. Often a client’s bespoke schedule of services will be more prescriptive about the individual tasks that the architect must carry out, but it will be rare for a client to propose a schedule of services that bears no relation at all to the RIBA stages. An architect will not be required to perform every service contemplated by the RIBA stages on every project, and there may be additional client requirements on individual projects, but the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 and stage descriptions in the various task bars set out in general terms the potential extent of an architect’s role.

The RIBA Standard PSC 2018 schedule of services section also contains a number of fundamental role specifications which may be agreed with a client for a particular project. An architect may be appointed to carry out one or a number of the separate defined roles; although when appointed as lead designer their services will include not only the lead designer role specification, but also the architect/architectural designer role specification. When an architect is appointed to perform a specified role as set out in the schedule of services section, they are generally responsible for the performance of the stated activities that form part of that role specification throughout – over the course of all the RIBA stages for which the architect is appointed.

The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 sets out the roles to be contained in the various RIBA appointment documents, including the RIBA Standard PSC 2018. The roles comprise:

- Client

- Client advisor

- Project lead

- Lead designer

- Architect

- Building services engineer

- Civil and structural engineer

- Cost consultant

- Construction lead

- Contract administrator

- Health and safety advisor

The most important of the role specifications are described below – those of project lead, lead designer, architect and contract administrator. The schedule of services to PSC 2018 excludes the role of principal designer – the health and safety advisor contemplated by the Plan of Work – but that role is covered under a separate professional services contract, the RIBA Principal Designer PSC 2018.

The project lead and lead designer role specifications

The project lead services are always required, whether or not other consultants are appointed. Dale Sinclair’s books, Assembling a Collaborative Project Team (2013, RIBA Publishing) and Leading the Team: An Architect’s Guide to Design Management (2011, RIBA Publishing), consider both project team formation and design co-ordination. The project lead and lead designer roles, and the duties undertaken by them, are central to the design process and the delivery of a successful project. On the vast majority of projects, the architect will be appointed to undertake both roles.

What skills are required to carry out these duties? Leading the Team covers this area and comments as follows:

The practical measures that should be taken by a project lead and lead designer in order for them to be considered to have exercised reasonable skill and care in the performance of their duties are also considered in detail in Leading the Team.

The architect's (as designer) role specification

The duties to be carried out as part of this role specification apply equally if the architect is appointed as lead designer. The architect’s duty extends beyond using reasonable skill and care to ensuring that the content of their designs is accurate and adequate in terms of functionality, impact and buildability; the architect must also use reasonable skill and care to provide designs that can be built safely, and maintained safely and cost effectively. The architect’s duty in this role also encompasses self-management – for each RIBA stage the architect must establish a programme for the performance of their own services, and the architect must have due regard for the cost of implementing their design.

The contract administrator's role specification

The RIBA role specification begins with the architect inviting tenders and then working with the client to appraise the tender returns. The contract administrator’s role specification also includes:

- preparing the building contract and arranging for signatures

- the actual administration of the terms and mechanics of the building contract

- liaising with other consultants to gather information sufficient to enable the contract to be properly administered. The role of the architect as contract administrator is considered in detail in the next chapter of this book.

7.2.2 The RIBA Plan of Work 2013

The RIBA Plan of Work 2013, which can be customised to meet project- or practice-specific requirements, is available at www.ribaplanofwork.com. It organises the process of briefing, designing, constructing, maintaining, operating and using building projects into a number of key stages and task bars (Figure 7). Architects should bear in mind that the RIBA stages and task bars are indicative rather than prescriptive; the precise content, sequence and any overlapping of stages and tasks will be governed by the procurement route adopted for the project. The RIBA Job Book contains detailed discussion and visual representation of the potential stage sequences by procurement method.

Figure 7 RIBA Plan of Work 2013 stages

The major advantages of the Plan of Work 2013 are its flexibility and adaptability. The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 is suitable for all forms of procurement and can be tailored to project, practice and client requirements. Project-specific or practice-specific versions can be generated electronically from the basic RIBA Plan of Work 2013 template.

The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 sets out eight stages and eight task bars Stages 0–7 are aligned with the Construction Industry Council’s schedule of services and the government’s ‘Digital Plan of Work’, enabling greater integration of architects within the wider construction industry.

The stages are fixed, but certain of the task bars contain content which can be varied, used or not used as appropriate to the needs of the project. The task bars relating to Procurement, Programme and Planning are variable; the Sustainability Checkpoints and UK Government Information Exchanges task bars may be ‘switched’ on or off altogether.

7.3 Strategic Definition, Preparation and Brief: RIBA Stages 0 and 1

7.3.1 Defining the client's requirements through development of the brief

Stage 0 emphasises the need for a strategic brief and definition of a project prior to creation of an initial project brief. It is intended that the strategic appraisal will address issues as fundamental as whether a new building is required at all, or whether a refurbishment, extension or a rationalised space plan would be more appropriate.

During Stages 0 and 1 the architect must take reasonable steps to establish whether the project envisaged by the client is feasible and buildable. Everything starts with the client’s initial statement of requirements, describing the building required by the client and the actions necessary to achieve it. This may begin as a detailed document produced by the client or, with less experienced clients, it will typically be a document produced by the architect following discussions with the client of their needs, objectives and business case. On the basis of this initial statement/brief it is the architect’s duty to complete feasibility studies and present options to the client to allow them to decide whether it is realistic and desirable to proceed.

The initial brief should be as comprehensive as possible. Any development of the initial brief should be recorded in writing. Fee and timescale will be based on an assessment of the initial project brief; record in writing any necessary adjustments as the initial project brief develops, along with the client’s agreement to any increase in your fee estimate or overall timetable.

Establishing feasibility and a usable brief will involve an investigation by the architect of the site itself, having obtained from the client all the information reasonably necessary for the architect to ensure that the initial project brief is as accurate as possible, including such information as site ownership and boundaries, proposed use of the building (including individual areas within the building), desired lifespan and time for delivery. It is the architect’s responsibility to check who precisely the client is and whether the party providing the information does so with the client’s authority. The architect should also be mindful to check the information they are given by the client against their own observations of the site:

- Do the dimensions of the site or its topography call into question the feasibility of the project?

- Is the client’s budget realistic?

- Is ground investigation of the site required and, if so, who should the client engage to carry out the survey?

It is good practice to develop a comprehensive checklist questionnaire to establish the client’s needs and objectives, business case and possible constraints on the development. The architect should also meet with the client as often as necessary to discuss their responses until they are sure that the initial project brief fully expresses the client’s wishes and that no important detail has been left out.

The architect may during these stages be expected to advise the client on the need for the appointment of other specialist consultants, such as a quantity surveyor or project manager, with whom the architect might be expected to work to produce an initial cost plan and overall programme.

7.3.2 Advising the client on procurement

During Stage 1, the architect is likely to be required to advise in relation to the need for a building contractor and the most appropriate form of ‘procurement route’ (traditional contracting or design and build, for example) and form of building contract.

To allow for compatibility with all forms of procurement, the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 has a generic Procurement task bar. Users generating a bespoke RIBA Plan of Work can select the type of procurement from a pull-down list. The practice- or project-specific Plan of Work subsequently generated will contain a task bar that includes the specific procurement and tendering activities at each stage for the chosen procurement route. On many projects, the procurement route is likely to be considered and agreed during Stage 1. In such circumstances a tailored project-specific Plan of Work can be generated at the end of Stage 1 to reflect the chosen procurement route.

While it is recommended that a project-specific Plan of Work is created at the end of Stage 1, the pull-down options in the electronic version allow a degree of flexibility. If the procurement strategy, or for that matter the planning strategy or project programme, have not been settled by the end of Stage 1, a holding bar can be placed in the project-specific RIBA Plan of Work 2013 and a new plan generated when the outstanding items have been finalised.

Procurement advice is not always the architect’s responsibility. The architect’s appointment should make clear whether they have a role to play in this area; often this will be the responsibility of a project manager or quantity surveyor, or the client may require input from all three. Entire books have been dedicated to the task of selecting the best procurement route for a project, but the relevant factors to take into account are largely common sense. The aim is to identify the client’s optimum balance between the following:

- cost control

- timing of completion

- quality of construction

- risk sharing

- client control over design.

7.4 Concept Design and Developed Design: RIBA Stages 2 and 3

The architect has a wide-ranging role during these stages. They will be reviewing the procurement route and advising the client in relation to, among other things, project costs and statutory requirements, while also developing and reviewing their design and co-ordinating it with the designs of the other consultants.

7.4.1 Reviewing the procurement route

The procurement options can and should be refined after Stage 1 to take account of the development of the brief and any other relevant new information. By the time the tender documents are issued (Stage 4 – although depending on the procurement route, the tender or first stage tender may take place earlier than this stage) they will need to be specific about not only the procurement route but also the precise form of building contract to be used. The architect’s duties, in addition to advising the client on the form of building contract, include giving advice on the need for any amendments to the contract terms to suit the particular needs of the project or the client, advising on the choices to be made when certain optional clauses are available within a contract (dispute resolution methods, for example, or whether to sign a contract under hand or as a deed) and, very importantly, advising on the need for the client to take further specialised legal advice.

The architect’s duty to exercise reasonable skill and care demands that the various choices are presented and explained to the client, and that the client is enabled to make an informed decision in each case. It is important that the client understands both the advantages and disadvantages of the available options. Advice to the client is an ongoing process. If, once the client has made their decision, it subsequently becomes apparent that a change in circumstances means that the selected route is no longer the most suitable, it is the architect’s duty not only to be alive to the issue but to bring it to the client’s attention and advise again on the best course of action.

There are numerous forms of construction procurement and an even greater number of standard form building contracts. The most popular options are ‘traditional’ contracting, design and build, and ‘management’, whether management contracting or construction management. These options are considered in more detail below in the context of RIBA Stage 4.

7.4.2 Providing and revising cost estimates

During these stages, the architect may be expected to provide information for cost planning and take responsibility for the provision of initial cost estimates and the revision of these estimates during the course of the project. These services may be provided by the architect in lieu of a quantity surveyor, or the architect may assist a client-appointed quantity surveyor in this role. If the client wishes the architect alone to assume this role, it may be appropriate for the architect to engage their own quantity surveyor. In practice this rarely happens, but where it does, the client is entitled to assume that the architect will be responsible for providing cost information using the requisite degree of reasonable skill and care set out in the architect’s appointment. The client will bring an action against the architect in the event of negligence; it will be for the architect to bring an equivalent claim against their sub-consultant if necessary.

Will the architect have satisfied their obligation to exercise reasonable skill and care simply by engaging a suitably qualified quantity surveyor as a sub-consultant? Can they use this as a full defence against the client’s claim for negligence? The answer is, maybe. The court in the case of Co-operative Group Limited v John Allen Associates Limited (at paragraph 180) said that an architect can discharge their duty to use reasonable skill and care by relying on the advice of a specialist provided that the architect acts reasonably:

- Was assistance sought from an appropriate specialist?

- Was it reasonable to seek assistance from another professional at all?

- Was there information which should have led the architect to give a warning?

- Does the client have an alternative remedy in respect of the specialist’s advice?

- Should the architect have advised the client to seek advice elsewhere?

- Should the architect have sought professional advice before engaging the specialist?

7.4.3 Ensuring compliance with statutory requirements

During these stages, the architect has to consider their design and the project overall in the context of a number of statutory requirements, and must advise the client accordingly. The architect will need to:

- consider their role under the applicable health and safety legislation

- make applications for planning permission, listed building consent and conservation area consents as appropriate

- advise the client in relation to any party wall notices that may be necessary.

One further important statutory requirement, Building Regulations approval, is usually sought later, during Stage 4 (section 7.5.1).

The architect's role under health and safety legislation

The architect has a duty during these stages, and throughout the project, to:

- advise the client of their duties under the Construction (Design and Management) Regulations 2015 (CDM Regulations) and other health and safety legislation

- comply with their own duties as a designer under the CDM Regulations, as well as their duties under other health and safety legislation

- if the architect is not acting in this capacity itself, assist the principal designer by providing information to them and co-operating with them and advising the client to require other members of the project team to do the same.

The CDM Regulations apply to all projects, with limited exceptions, where there is more than one contractor. Any building project that will involve more than 20 people on site at any time and will last longer than 30 days, or will involve more than 500 person days of construction work, must be notified to the Health and Safety Executive. The CDM Regulations impose statutory duties on designers and contractors, and also on clients – whether or not the work in question is for the client’s own residence.

The CDM Regulations require the client to take reasonable steps to ensure that any contractor or consultant appointed on a project (including the architect) is competent to carry out their role. The client is also obliged on each project to appoint a consultant health and safety compliance specialist – the ‘principal designer’. This may be the architect, if they have the appropriate skills and experience, but otherwise the architect will have a duty to be aware of the principal designer’s role and to co-operate with and provide information to them as reasonably necessary.

Even if the architect is not the principal designer, the duties of a designer under the CDM Regulations are extensive. The designer should not commence work, other than initial design work, on a notifiable project unless a principal designer has been appointed. In practice this means that an architect should not progress work beyond Stage 1 in the absence of a principal designer. A designer has to ensure that they are competent for the job and also that that the client is aware of their duties in relation to the CDM Regulations before beginning work on the project. When preparing the design, the designer must as far as is reasonably practicable avoid creating risks to the health and safety of those who will be carrying out the construction work, and also of those who will use, maintain, clean and repair or eventually demolish the completed building. The designer has an ongoing duty to review their design risk assessments during the course of construction of the project, whether instructed to do so or not.

While it remains relatively rare for designers to face health and safety charges, it is not unheard of. In 2010 the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) decided to prosecute both the contractor and the designer, Oxford Architects Partnership, in relation to the death of a technician who fell over a low parapet while repairing an air-conditioning system on a recently completed building.

The architect pleaded guilty to failing to take safety into account in the building’s design, and not ensuring that the project’s planning supervisor (principal designer in the post-2015 terminology) considered design safety. It was found by Bristol Crown Court that the technician had to climb a ladder located less than a metre in front of a low wall at the edge of a flat roof to get to the cooling unit; the access ladder was too close to the edge, the parapet was too low and the ladder was ‘very wobbly’.

The HSE subsequently commented that the architects had created the risk by changing the design of the build; originally the air-conditioning unit was going to be placed elsewhere. Neither the contractor nor the architect had reviewed the project risk assessment after the building design changes, because they were rushing to complete the project. The HSE prosecution under the CDM Regulations led to the architect being fined £120,000 and ordered to pay £60,000 in prosecution costs.

Applying for planning permission

The architect’s services will always include an obligation to apply for any necessary statutory consents and approvals, one of which will usually be planning permission. An architect must be able to advise the client as to what (if any) permission is required, who to approach and how best to go about obtaining it, having first reviewed any relevant local authority guidance as well as the statutory requirements, in particular the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. The client should also be advised of the likely time and costs associated with making the application for planning permission.

It is very important the client understands that no architect can warrant, undertake or guarantee that they will obtain planning permission, or Building Regulations approval for that matter.

An architect must reject an obligation to ‘obtain’ such approvals, as the ultimate decisions are made by third party local authorities, outside the architect’s reasonable control.

Planning control is essentially concerned with ensuring that the right projects are built in the right places, and ensuring the harmonisation of new buildings and building alterations with their surroundings. Planners are concerned with the environmental impact generally of developments, their usability and the impact of the development on third parties. Some brief official guidance covering planning and Building Regulations approval is provided on Directgov’s Planning Portal website:

- www.planningportal.gov.uk

Certain types of small-scale alterations and extensions to buildings come within the definition of ‘permitted development’, for which planning permission is not required, but for the most part any substantial project will require planning permission.

Applications are made by way of a development plan to the local planning authority; again, the Planning Portal website has a powerful search engine, which will tell you the name of the appropriate local planning authority based on the postcode or site location information you provide. The Planning Portal also provides information about whether the local authority accepts planning applications through the website, along with links to guidance produced by the relevant local authority, and contact addresses and phone numbers. There is no shortage of freely available information that the architect can use to refine their development plan in accordance with the relevant local authority’s stated requirements, to maximise the chances of making a successful application.

As well as the full application for planning permission, based on a fully realised development plan, it is possible to apply for ‘outline permission’, a confirmation that the local authority looks favourably on the development in principle, subject to acceptance of the detailed development plan at a subsequent date. An application for outline permission can save a good deal of time and expense if the architect reasonably considers that, for example, the proposed project would be unusual for the particular location being considered.

The architect must be very sure of the accuracy of their drawings when submitting the planning application; the architect will potentially be liable to the client for the losses incurred if permission is not granted because of a failure by the architect to exercise reasonable skill and care in any aspect of making the application. The architect should consider the implications of any deviations from the permission granted in the final built project. It is not sensible to change a design at all once full planning permission has been granted; some local authorities will require the application to be re-submitted in its entirety, and any significant variation will require a further planning application.

One final aspect of the architect’s duty, particularly in the context of a design and build project, is to ensure that the conditions (if any) on the basis of which planning permission was granted are properly communicated to the party – client or contractor – who has assumed the risk of satisfying those conditions.

Planning applications are typically made at the end of Stage 3, using the output from that stage. However, the RIBA’s member consultation during the development of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 identified a common trend among clients to request that planning applications be submitted earlier in the process, for example using an enhanced concept design at the end of Stage 2.

Dealing with party wall issues

The Party Wall etc. Act 1996 came into force on 1 July 1997 and applies to the whole of England and Wales, apart from the four Inns of Court in London. For a more detailed review of the law and practice relating to party walls, specifically aimed at architects, see Party Walls: A Practical Guide by Nicol Stuart Morrow (RIBA Publishing, 2010).

The 1996 Act defines party walls, party fence walls and party structures, and sets out both the rights and obligations of property owners involved in building work affecting such walls and structures at the boundary of their properties. The work covered by the 1996 Act may be the construction of a new party wall or structure on a boundary, the alteration or repair of existing party walls or structures, or the excavation of land within a specific distance and angle, prescribed by the 1996 Act, of a party wall or structure. The Act sets out the procedures for notification of neighbouring owners, which must be followed if a building owner wishes to carry out any such work, as well as the mechanism for the appointment of party wall surveyors, if necessary to resolve a dispute about the proposed work. An architect owes a duty of care to their client to be aware of the requirements of the 1996 Act and to advise their client accordingly. It is also the architect’s duty to ask the right questions of their client, and make reasonable enquiries if the client is unable to provide the necessary information, about the nature and extent of neighbouring interests in the first place, as well as to bear in mind the management of those interests when producing their design.

A building owner proposing to carry out work covered by the 1996 Act must give their neighbour written notice; depending on the type of work proposed, the notice must be given either 1 or 2 months before the work is due to start. The neighbouring owner then has 14 days to indicate their agreement or objection to the works taking place; silence is taken as an objection. If the works are not agreed, a dispute is said to exist; party wall surveyors must then be appointed by each owner to agree a party wall award. It is possible for both parties to agree a single, impartial surveyor to make the award.

A suitably experienced architect – there is no required formal qualification – may act as their client’s party wall surveyor. A party wall surveyor performs a statutory function and their role is to impartially facilitate the resolution of disputes under the 1996 Act, not to fight their client’s corner. This can be a difficult balance for the architect to strike, and for the client to understand. In the event that an architect is required to act as party wall surveyor, it is very important that the architect explains fully the different nature of their role in performing that function; the client is not generally permitted any input in the resolution of the dispute once the mandatory appointment of party wall surveyors has taken place. The architect should also be sure to conclude a separate written appointment covering the party wall surveyor role. If there is any doubt about whether the architect will be able to maintain impartiality, or whether the client will allow them to, then the architect should suggest that the client engages an alternative architect or surveyor to take on this role.

7.4.4 The designer's duty to the client

An architect’s basic obligation, in the absence of any higher contractual obligation, is to produce and develop their design using the reasonable skill and care of the ordinary competent architect. The architect should never accept an absolute obligation in relation to their design; some clients may expect the architect to guarantee a particular outcome by warranting that their design will be fit for the stated purpose. An architect simply cannot give such a guarantee, and their PII policy will not cover claims made on such a basis.

The architect’s choices in terms of the specification of materials and workmanship must be such as would be supported by a responsible body of their peers. The design itself must be ‘buildable’ – ordinarily this will mean that the design can be constructed by a building contractor with the skills and experience that might reasonably be expected of them. In some circumstances the architect may be entitled to assume that the building contractor will possess a special higher degree of skill and experience, for example on a high-value, high-profile or architecturally unique project. Generally, however, if the architect has made unrealistic assumptions about the standard of workmanship required to build out the design, they will be found to have performed negligently.

The architect must also exercise reasonable skill and care in verifying the assumptions on which their design is based, or in ensuring that the client knows additional information is required to verify the assumptions on which the architect has based their design. As an illustration, if an architect is not to be considered negligent, they must have based the site levels in their drawings on sufficient knowledge of the relevant site surveys. A designer also has a duty to warn other designers if their design cannot be fully relied on without further verification of the design assumptions.

As mentioned above in the context of specialist advice on cost estimates, if the architect engages or otherwise relies on the advice of a specialist in producing an element of their design, this may amount to a discharge of the architect’s duty to use reasonable skill and care in producing their design, but only if in all the circumstances it was reasonable for the architect to have relied on the advice of the specialist in question.

The designer’s duty is not confined to producing a design that appears reasonable and buildable on paper. It is a continuing duty during construction that may be triggered by events on site. If the architect is engaged by the client to perform inspection duties during the construction phase, the architect must use reasonable skill and care to react to ‘trigger events’ by reviewing their own design as necessary; they must check that it will work in practice, and must correct any errors that become apparent, issuing instructions to the contractor for remedial work if required. The architect must react to trigger events and act immediately, not wait to see if a problem resolves itself; an architect can be negligent by omission (a failure to act) in the same way that an architect’s acts may be negligent.

A trigger event is any circumstance during the building phase which would alert a reasonably competent architect to the potential need for review of the design, and may include queries received from the contractor as well as circumstances on site that the architect has directly observed. It is unlikely that the ongoing duty to review the design exists in the absence of a trigger; it is also unlikely (although technically possible) that the duty to review persists after practical completion of the works.

There is a more detailed commentary about the architect’s duties of inspection below, in the context of RIBA Stage 5 (see section 7.6), and comprehensive information is available in the RIBA’s Good Practice Guide: Inspecting Works (2009).

7.5 Technical Design: RIBA Stage 4

7.5.1 Seeking building control approval

It is the architect’s duty to advise the client which Building Regulations the project will have to comply with, whether Building Regulations approval will be required and, if so, to use reasonable skill and care to give the notices necessary to obtain it. As with planning permission, an architect must not accept an obligation to obtain Building Regulations approval – that is not within the architect’s reasonable control.

Building Regulations aim to secure the standards of health and safety for those who will use or be otherwise affected by buildings, and to set the basic standards to be achieved in the design and construction of buildings to promote energy conservation and the welfare and convenience of disabled people. The statutory framework for building control in England and Wales is created by the Building Act 1984 and the Building Regulations made under the Act. The Building Regulations focus on the safety, durability and sustainability of design, building methods and materials used. Building Regulations approval is likely to be required for a broader range of work than planning permission, including even some small-scale internal alterations, such as loft conversions.

Directgov’s Planning Portal website is useful, providing:

- basic guidance on building control requirements

- a search engine for identifying the correct local authority for you project

- links to the relevant local authority’s own building control guidance.

Two types of building control service are available:

- the building control service provided by the relevant local authority

- an approved private building inspector engaged by the client.

An architect must be competent – through their own experience and knowledge of the available options, and their advantages and disadvantages in particular circumstances – to advise the client in relation to which service would be most appropriate, and also which procedure would be most appropriate:

- the building notice procedure: a simple notice to the local authority of the developer’s intention to carry out works, which the local authority does not ‘accept’ or ‘reject’, or

- the full plans procedure: requiring the deposit of full plans for the development with the local authority or approved inspector; if using the services of a local authority, the plans must be accepted or rejected within a period of 5 weeks, which may be extended to 2 months by agreement.

The architect should also be able to advise on the timings and associated costs of the different procedures.

Following the official guidance is not enough to satisfy the architect’s professional duty of care. If in any doubt about the nature, extent or content of the advice to be given to the client, the architect should take their own legal advice.

One word of caution; the architect may produce design documentation that is approved by the building control service, but the architect must still comply with the requirements of the Building Regulations themselves and not rely solely on this approval. There is an important potential advantage in using the services of a private building inspector rather than the local authority service; a private inspector is more readily accountable, must carry PII and will be liable to a claim for negligence in the event that they approve drawings which do not comply with the Building Regulations.

An architect may also be required by a client to carry out a Fire Safety Risk Assessment – in relation to non-domestic premises – for the purposes of the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005. The 2005 Order replaced most of the previous fire safety legislation, and obliges anyone who has ‘some level of control’ in relation to non-domestic premises to take reasonable steps to reduce the risk from fire and ensure safe means of escape in the event of a fire. A checklist setting out in detail five key steps to complete the assessment, published in June 2006, is available free of charge at gov.uk.

7.5.2 Tenders

Identifying the procurement route

By Stage 4 (or potentially much earlier) in order to obtain meaningfu tenders, the procurement route and proposed form of building contract must have been defined. The most popular options are discussed below in broad terms. There are many shades of difference between ‘pure traditional contracting, for example, and ‘pure’ design and build, and the roles and responsibilities of the architect may vary considerably even on two projects procured on the same fundamental basis.

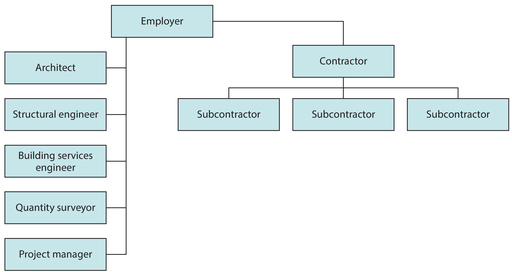

Figure 8 Traditional procurement route

Essential features of traditional contracting: This probably remains the default option for many less-experienced clients on low-value projects. An architect is appointed by the client to carry out and substantially complete the design in sufficient detail to enable tenders to be obtained; the contractor tenders on the basis of that substantially completed design for the job of building it out. The client signs the building contract with the contractor, and professional appointments with the architect and any other consultants. The client is protected by these direct contractual relationships and may sue any of these parties for breach of contract if they are responsible for a design or construction defect. If the contractor engages subcontractors to carry out specialist elements of work, these subcontractors are likely to be required to sign collateral warranties to establish a direct contractual relationship with the client.

If the production information is issued in sufficient detail to enable meaningful tenders to be obtained, and the ‘bills of quantities’ (setting out the quantities of each element required to complete the works) are also sufficiently detailed and accurate, traditional contracting offers the client the closest thing to price certainty. It is possible to opt for traditional contracting without specifying quantities; the measurement risk is with the contractor in such a scenario, and as a result the client may receive fewer bids for the work.

The potential for a degree of price certainty will be to some extent lost if the design is not sufficiently detailed at tender stage. If there is insufficiently detailed design or quantities information at tender stage it is an option (although rarely used in traditional contracting) for the architect to consider advising the client to engage in a ‘two-stage’ tender. In this process, initial tenders are received on the basis of the available information and, once a preferred contractor is identified, the second stage of the process involves firming up the price for the works as the design becomes more detailed. Two-stage tendering is a possibility whenever a client is keen to get a project up and running quickly, and where the development of a design will benefit from the contractor’s early input on the method of construction.

In addition to cost certainty, traditional contracting also emphasises quality of detailing, if not necessarily construction – where there is no contractor design input whatsoever, the design team designs, the contractor builds, and both are subject to the direct control of the client. The lines of contractual responsibility are generally clear-cut in the purest form of traditional contracting, and this way of procuring construction is intuitive, even for an inexperienced client.

There are two potentially important disadvantages to traditional procurement. Because of the need for production information to be issued in sufficient detail to form the basis of meaningful tenders, work on site may begin later than would be the case with other procurement routes – for example, design and build or a management contract. If reducing the overall programme for the project is an important issue for the client, the architect should consider steering them towards a procurement route in which design development and work on site may proceed in parallel, although in practice traditional procurement can match the timescales produced by other procurement routes if operated efficiently.

The second important disadvantage for the client is the lack of a single point of responsibility; in any dispute about defects in a building, there are always likely to be arguments about whether the defect was caused by faulty design or faulty construction work. The client’s legal fees will increase considerably if it is necessary to bring actions against both builder and designers to recover damages.

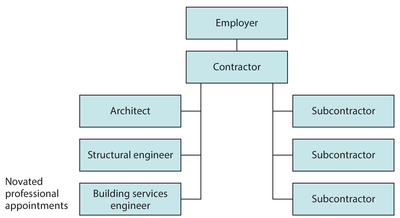

Essential features of design and build procurement: The main advantage for the client of design and build procurement, in its purest form, is the simplicity of a single point of responsibility. The contractor is responsible for the whole of the design and construction of the finished project. The client has a contractual relationship with the contractor through the building contract and will want to receive collateral warranties from any design professionals and specialist subcontractors engaged by the contractor. Design and build construction can be relatively quick because the building work can potentially begin before the design is finalised. There is a degree of cost certainty too – the contractor is generally expected to commit to a fixed lump sum even though the design is still to be fully developed. As a result, the client should expect the contractor to build a premium into their price to take account of the risk of making the price commitment based on incomplete information.

The perceived main disadvantages of design and build are the potential for:

- lack of quality in detailing

- lack of incentive for innovation

- loss of control over the detailed elements of the specification.

The client effectively hands over control, and it is down to the contractor to bring all the elements of design and construction together. This is the price the client pays for passing on the bulk of the project risk.

In reality, the design work is likely to be carried out by the same parties under both a traditional procurement route or design and build. There are contractor-designed elements (performance-specified work) in very many traditional projects, often undertaken by specialist subcontractors, and in many design and build projects the majority of the design work will be carried out by specialist subcontractors along with the architect and other consultants originally engaged by the client but subsequently ‘novated’ to the contractor. The key issue for an architect in this position after novation is to be satisfied that they have explained fully enough to the contractor what additional detailing the contractor may need to address in their own design.

Figure 9 Design and build procurement route

Two-stage design and build procurement, where specialist subcontractor design can often be completed before the building contract itself is agreed, offers potential advantages for the architect, as early contractor involvement means early sharing of the design responsibility.

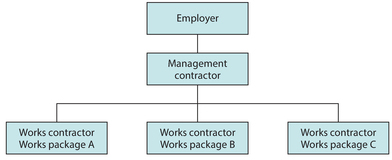

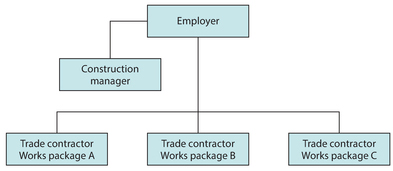

Figure 10 Management contract procurement route

Essential features of management contracts: Management contracting and construction management are two broadly similar concepts which offer particular advantages to a sophisticated and experienced client. Both are reliant on the skills of one key appointee – the management contractor or the construction manager. Their skills in managing the timescale and placing contracts with specialist contractors for the completion of elements (packages) of the work can allow the client to enjoy time and quality benefits. They also have the advantage of flexibility to modify and develop the design deep into the construction phase.

This all comes at a price, of course. There is an inherent uncertainty as to the final cost of the project with either management route, and the risk is almost entirely with the client. The manager’s job is to manage responsibility for actual performance failings will lie with the individual contractor or consultant. The scope for overlapping liabilities is great and can make it difficult for the client to identify where final responsibility lies in the event of a problem.

What are the architect's fundamental duties during the tender process?

At Stage 4 it is the architect’s duty to prepare production information in sufficient detail to enable a tender or tenders to be obtained. The design must have reached a stage of development – including all architectural, structural and mechanical services information and specifications – to enable tenders to be sought. The level of detail produced by each designer will depend on whether the construction on site will be built in accordance with the information produced by the design team or based on information developed by a specialist subcontractor. The technical work of the core members of the design team should be completed during Stage 4. It is important that any fabrication design, which can only be completed after the contractor is appointed, is clearly identified in the tender documents.

It is also part of the contract administrator’s role specification – and consequently the architect’s duty if they are appointed to perform this role – to invite and appraise a tender or tenders. The architect’s duty in this context is generally understood to be the preparation and/or collation of the tender documentation in sufficient detail for a tender or tenders to be obtained.

In reality it is not uncommon for a quantity surveyor to actually issue the tenders, even if the architect is appointed as contract administrator, but it is best practice for this to be part of the contract administrator’s function.

The tender documents must encompass far more than a statement of the client’s vision of what they want built, in a specification and contract drawings. The architect (or quantity surveyor) has to consider the desired end product in the context of:

- the client’s budget

- the overall programme

- which other parties (contractors, consultants) will need to be engaged

- what those other parties’ roles and responsibilities will be

- which building contract and procurement route should be used.

The architect is also required to consider and advise the client on the extent of the architect’s own responsibilities.

The architect also has a role in assisting the client to appraise the tenders received, most likely in a formal report to the client. The assessment of tenders and selection of the building contractor is best seen as a collaborative process, but many clients will ultimately be looking to the architect for a recommendation. The exercise of reasonable skill and care in this context requires that the architect’s advice must be logically supportable. Assertions within a tender relating to the contractor’s skill, capacity, experience, reputation or insurance cover should be checked by the architect; information that is not verifiable should not be presented to the client as fact. The architect’s report should cover:

- a review of the tenders received by cost

- a review of the tender sums against the pre-tender estimate and project budget

- a review of tenderers’ proposed contract periods

- an assessment of the tenderers’ ability to comply with project requirements

- a note on non-compliance with the tender requirements and other errors and omissions

- conclusions and recommendations.

For the purposes of contract law, a contractor’s tender is usually an ‘offer’ to carry out the work for the price stated by the contractor. It is the architect’s responsibility to make sure the client understands the rules for acceptance. The contractor’s tender can generally be withdrawn any time before it is accepted; the architect must also make sure that the client understands any rejection of the tender or partial rejection (‘you can have the job if you do it for 20% less’) will mean that the tender cannot subsequently be accepted, though the contractor may accept the client’s counter-offer to take the job on at a different price or on the terms of the original tender. The architect must also bring to the client’s attention any time limit for acceptance that the contractor has put in their tender.

What if no tenders come in on or below the client’s budget? That is not necessarily evidence that the architect has negligently over-designed or over-specified in the tender documents – the general climate for tenders may just be high because there is so much work about – but disappointing tenders can damage the architect/client relationship and lead to claims, whether justified or not. An architect should always keep well informed about the likely level of tenders in order to manage the client’s expectations, and must ensure there is a clear paper trail showing how the architect has used reasonable skill and care in linking decisions about design or specification back to the client’s own requirements.

Additional advice in relation to tendering is available in the form of the JCT Tendering Practice Note 2017.

7.6 Construction and the architect's duty to inspect: RIBA Stage 5

The architect’s services may include a duty to visit the construction works as they are being carried out on site in two capacities:

- as designer

- as contract administrator.

The architect will be looking to use their visits to:

- assess progress and quality

- meet the other professionals and contractors on site as necessary

- give – or gather information to give – any required comments or approvals; for example, in relation to design information provided by contractors or specialists

- gather the information to perform their contract administration duty – to enable them to issue certificates, architect’s instructions and notices.

An architect should never agree a service requiring ‘supervision’ of the works. For around the past 30 years the RIBA standard forms of appointment have referred to a service of periodic ‘inspection’, which the case of Consarc Design Limited v Hutch Investments Limited confirmed is a less onerous duty than ‘supervision’. Supervision, unlike inspection, may potentially involve the architect in giving directions as to how the work

Figure 11 Construction management procurement route

should be carried out; an architect has no authority, ordinarily, to direct a contractor or subcontractor in this way.

The duty to inspect is onerous enough. Going about the task without method, or rigidly sticking to a pre-conceived site visit programme, are not going to be enough to amount to reasonable skill and care. The architect’s inspection regime must be tailored to the project in question, not based on personal habit, and must be appropriate to the precise work being carried out on site at any particular time during the course of a project. The frequency of site visits will vary according to the stage reached in the works. Each visit should have a definite purpose based on the current state of play. Before going on to site the architect should have a clear idea of what they are looking for rather than waiting for something to jump out at them. That said, it is a good idea to combine method with an element of unpredictability, to limit the potential for an unscrupulous contractor to carry out sloppy work they know can be covered up before the next targeted inspection of that element. Vary the times or dates of inspections, and always indulge in a non-specific poke around outside your main areas of inspection during a visit.

A court’s assessment of an architect’s performance in carrying out their inspection role will not be results-based. An architect undertakes to exercise reasonable skill and care; they do not guarantee a particular result. It is a given that some defective work, even potentially serious defective work, may not be identified even by an architect exercising reasonable skill and care.

The discharge of the architect’s duty is all about the adequacy of their approach.

The architect must therefore take particular care:

- in gathering information before a visit

- in judging when and how often to visit, and what to look at on a particular visit

- in identifying what level of detail is appropriate for inspecting a particular element of work in the context of its completeness

- in assessing what actions are necessary when the architect gets back to their office.

The test an architect must satisfy is: would a responsible body of architects have discharged their inspection duty in the same way? The architect should make sure they keep a thorough contemporaneous log of their site inspections, ideally chronologically in a bound notebook, in case the architect’s actions ever need to be considered by a court or other tribunal. It is worth noting that ordinarily the architect’s duty to inspect the works and identify defects is owed to the client alone; the contractor cannot claim against the architect for failing to identify the contractor’s own defects. This will not be the case, though, in the context of a design and build project where the architect’s appointment has been novated to the contractor and the architect has agreed a contractual inspection duty.

7.7 Handover and Close Out, and In Use: RIBA Stages 6 and 7

During the post-completion phase the architect advises the client in relation to the resolution of defects and makes final inspections as appropriate. In practice it is not uncommon on design and build projects for Stages 6 and 7 services to be limited or not required.

It is important that the architect ensures the client is aware that through this inspection role, the architect is not in any way assuming responsibility for the work of others. During Stage 6, the architect will also have a role in settling, or providing information to others such as the quantity surveyor to enable them to settle, the final account.

A phrase used increasingly in bespoke appointments is the need to ensure a ‘soft landing’ – in practical terms, for example, by providing copies of the operation and maintenance (O&M) manuals months (rather than days) in advance of project handover so that the client can be properly familiarised with the new building. The Building Services Research and Information Association has published a soft landings framework document to give structure to the obligations and procedures required to bring about a soft landing in practice:

- www.bsria.co.uk/services/design/soft-landings/

RIBA Stage 7 is dedicated to post-occupancy services. The architect may be required to advise in relation to the O&M of the completed building. It is good practice and common sense for the architect at Stage 7 to debrief with the client; to evaluate with the client how the building is performing post-occupation (known as post-occupancy evaluation) and to seek feedback from the client on how the architect and the other members of the project team performed during the course of the project.

This is an important way in which the architect can manage their legal risk. Debriefing post-occupation can give early warning of the factual presence of defects, but it can also give early warning of a client’s dissatisfaction and potential to bring a claim under the appointment. The debrief is an opportunity for the architect to manage the client’s expectations, to prevent actual or perceived problems turning into claims. Client feedback can also provide invaluable business development information for the architect. Previous RIBA Business Benchmarking Surveys have shown that around 55% of architects’ work is repeat business from existing clients.

The architect may also be required to provide services in relation to the resolution of disputes with the contractor or other members of the professional team. These services should always be considered an ‘additional service’, subject to an additional fee, because of the inherent unpredictability of the time and costs associated with providing such assistance.

Chapter summary

- The RIBA work stages as set out in the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 represent the industry standard approach for conceptually dividing a project into its constituent phases.

- During each of the RIBA stages, an architect is likely to be required to perform certain tasks on each project in which it is engaged – the Plan of Work sets out in detail the typical tasks required at each RIBA stage.

- An architect should recognise that their services are to be performed in the context of a complex framework of statutory regulation, including the Building Regulations, the CDM Regulations, planning law and the Party Walls Act.