Chapter 10

Disciplinary proceedings and dispute resolution

This chapter:

- describes in detail the professional disciplinary procedures for architects

- provides an overview of the main dispute resolution options

- reviews in detail the theory and practice of statutory adjudication, arbitration, litigation and mediation.

10.1 Disciplinary proceedings

The codes of conduct of both the ARB and the RIBA impose subtly different obligations on architects in terms of their professional behaviour. Breach of either code will leave the architect liable to disciplinary action. Only the ARB, as a statutory body backed by the power of government, has the capacity to impose fines or take away the architect’s right to practise architecture altogether, by suspending or striking off individuals from the Register of Architects. The RIBA for its part may caution members, reprimand members, or suspend or withdraw membership from those who fall foul of its disciplinary process. The RIBA controls who may use the title ‘chartered architect’ and who may use the letters ‘RIBA’ after their name. Removal of these and other benefits of RIBA membership can have a serious detrimental effect on an architect’s ability to practise.

In fact, if an architect is found guilty by the ARB following its disciplinary process and is suspended or erased from the Register, it is very unlikely that the RIBA would not also impose a sanction on that individual assuming (and it is not always the case) that the registered architect is also an RIBA member. If the ARB’s Professional Conduct Committee (PCC) has imposed any sanction on an RIBA member, that member will be given the opportunity to put a ‘plea of mitigation’ to an RIBA appraisal team as to why they should not be similarly sanctioned by the RIBA. If the ARB dismisses a case against a member which has also been submitted to the RIBA, an RIBA appraisal team will review the complaint and the member’s response, and will then make a decision as to whether the RIBA will also dismiss the case or pursue an investigation.

In practice, though, the ARB and the RIBA disciplinary processes have slightly different functions. Generally, the ARB is a client-facing body, concerned with issues of competence; the RIBA is more broadly concerned with professional integrity. The likelihood is that a complaint from a member of the public will be made through the ARB process, whereas issues arising between architects will be directed to the RIBA. If a complaint is submitted to the ARB and the RIBA at the same time, the ARB’s investigation will take precedence; the RIBA will require the member concerned to respond to a letter of enquiry in order to procure evidence from both sides for possible future reference, but it will then suspend any further investigation until the ARB reaches a decision.

10.1.1 Why is the ARB disciplinary process necessary?

From a consumer protection perspective, members of the public must be allowed, without risk of incurring legal costs, to raise issues of unacceptable professional conduct or serious professional incompetence in a public forum. To retain the confidence of the clients who instruct it, the profession must allow itself to be subject to this scrutiny. It is important also that the ARB is visible in performing its role; the list of guilty verdicts concerning cases of unacceptable professional conduct and serious professional incompetence is made publicly available, on the ARB website.

10.1.2 The ARB procedure in practice

The ARB Code sets out 12 standards, dealing with:

- conduct and competence

- client service

- complaints.

The Architects Act 1997 (the 1997 Act) provides that failure by an architect to comply with the provisions of the ARB Code does not necessarily constitute unacceptable professional conduct or serious professional incompetence. However, such failure may be taken into consideration in any disciplinary proceedings.

The initial complaint

It is extremely easy – and has to be, from a consumer protection perspective – for a member of the public to make a complaint to the ARB. A tick box complaints form is available on the ARB website, or alternatively the complainant may send a complaint to the ARB by post, fax or email. There is no cost to the complainant at any stage of the process.

The ARB is given power under the 1997 Act to investigate just two possible ‘offences’:

- unacceptable professional conduct

- serious professional incompetence.

If the actions or omissions complained of may amount to either unacceptable professional conduct or serious professional incompetence, the ARB is empowered to investigate the complaint. As part of this initial process, the ARB will send a copy of the client’s complaint to the architect, and ask for comments. Any reply will be sent to the complainant, and further comments requested. The architect is best served by engaging with the process from the outset: don’t be tempted to ignore correspondence in the hope that the matter will go away – it won’t. Failure to respond to the ARB regularly appears in its own right as ‘unacceptable professional conduct’ on the public list of adverse PCC decisions.

Formulation of the Investigations Committee and the PCC

An ARB Investigations Committee – a panel of three, always comprising one architect and two laypeople – then reviews the matter. The Investigations Committee may appoint an expert to produce further information; more usually further comments and documents are requested from the client and the architect in turn, and documentary evidence is gathered in this way. The Investigations Committee, independently or following receipt of a detailed report from its independent expert, will ultimately decide whether to:

- dismiss the complaint

- give the architect a formal written warning, or

- refer the matter to the PCC for a full public hearing.

The architect will be informed of this decision. The Investigations Committee has a non-binding commitment to reach a decision within 12 weeks of receiving the complaint.

If the Investigations Committee recommends a formal public hearing, this will take place before the PCC. The PCC is another panel of three, always comprising an architect, a solicitor (usually also the chairman) and a lay member of the public. The public hearing cannot take place until the ARB has settled its case and formally set out the grounds for complaint and how these constitute either unacceptable professional conduct or serious professional incompetence, or both. The ARB’s nominated solicitor generally a senior lawyer at a City practice, who acts for the ARB as they would for any other client, puts together a ‘Report from the Board’s Solicitor to the Professional Conduct Committee’. This is in effect the same as the particulars of claim in litigation, or an adjudication referral. The unfortunate impression given is that this is a report from one part of the ARB to another part containing recommendations about the architect in question, and that the architect then faces an uphill struggle to convince the PCC not to follow the recommendations in the report.

The architect's defence

Once the solicitor’s report is received by the PCC, a provisional date for a public hearing will be set and the architect will be notified. It is up to the architect to serve a formal defence to the PCC prior to the hearing, along with any supporting documentary evidence and witness statements, to put their side of the story. There is a degree of flexibility about the hearing date (extensions of time are not uncommon) and the timing for service of the defence – officially, a defence should be served no later than 2 weeks prior to the hearing date, but there are no prejudicial consequences if this cannot be complied with for legitimate reasons. Unofficially, it is best practice not to serve any significant new documents later than a week prior to the hearing date.

The hearing and the decision

The hearing itself is an approximation of a court procedure; it is adversarial, and temperatures can rise. The ARB’s solicitor acts as prosecutor and will directly question witnesses, including the architect. The architect or their legal representative may in turn ‘examine’ the complainant or any of the other witnesses, for or against them. The PCC panel may, and very often does, ask its own questions directly of witnesses. At the end of the hearing, which can last for several days in cases that involve complex issues or have generated a lot of paper, both the ARB and the architect get the chance to sum up their case. Sometimes the panel is able to give a decision on the day; in other cases, where a written decision seems appropriate, it can take months. The PCC is obliged to provide a decision as soon as practicable after the hearing, but this obligation is not as strict as it may appear; the PCC itself says when the ‘hearing’ ends. Logically, this may be expected to be the time when everyone stops talking and leaves the hearing venue to go home and await the decision, but the PCC has indicated in previous matters that the ‘hearing’ only ends when the panel finishes considering the evidence.

Mitigation, penalties and appeals

Once a decision of guilty or not guilty is given by the PCC, the architect has 30 days to request a third party review to consider any complaints of a procedural nature. The independent third party cannot consider the decision itself, and this is in no way an ‘appeal’ process. It is questionable what any architect would hope to achieve by requesting a third party review; perhaps if there was an obvious case of bias or unfairness, clearly evidenced, this would be something worth pursuing. At the end of the third party review process, the same PCC panel that gave the original decision is asked to decide whether there is anything in the independent reviewer’s report that would mean its decision should be reconsidered. However, this is an unlikely scenario.

Following the decision on culpability, if the verdict is guilty, the architect will be asked to provide a plea in mitigation for the panel to consider before making a decision on the appropriate penalty. This is not an opportunity to disagree with the decision itself; rather, it is a chance for the architect to persuade the panel that the penalty should be as light as possible, for example because of the architect’s previous good behaviour or their willingness to learn from the mistakes highlighted in the complaint, or because the available penalties would be excessive bearing in mind the facts of the matter or the particular circumstances of the architect.

Following mitigation – and again this decision may take weeks or even several months to come through – the PCC may:

- issue the architect with a formal reprimand

- impose a fine of up to £5,000

- suspend the architect from the Register for up to 2 years

- permanently remove the architect from the Register.

The PCC may impose a combination of penalties – or, in rare cases, no penalty at all.

An aggrieved architect may take a case to the High Court within 3 months of the date of the decision, if they consider that the decision made against them by the ARB PCC is unjustified. Considering the likely costs of such a process, and the slim chances of successfully showing clear bias or some other blatant procedural unfairness, this should not generally be considered.

Once an architect becomes subject to the ARB’s disciplinary process the effects can be profound, whether or not the architect is ultimately found guilty of serious professional incompetence or unacceptable professional conduct. If they are found guilty, the damage to an architect’s reputation can be hard to live down. The architect will not be entitled to recover the costs of defending themselves, whatever the outcome.

The best way to manage this process is to avoid having to engage with it.

Adopt strategies to ensure that you comply with the strict requirements of the ARB Code. Invest time in risk management more generally. If a client has a complaint, do not ignore it; if you engage with a complaint and manage the client appropriately at an early stage, there is every chance of avoiding a formal complaint being put before the PCC.

10.2 Dispute resolution: an overview

The nature of dispute resolution has changed dramatically in the past 20 years in all areas, but in construction in particular. On 26 April 1999 the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR) came into force, a single set of rules governing both the High Court and county courts. The overriding objective of the CPR (Rule 1.1(1)) is to enable ‘the court to deal with cases justly’. This includes (Rule 1.1(2)):

- (a) ensuring that the parties are on an equal footing;

- (b) saving expense;

- (c) dealing with the case in ways which are proportionate –

- (i) to the amount of money involved

- (ii) to the importance of the case

- (iii) to the complexity of the issues, and

- (iv) to the financial position of each party; and

- (d) ensuring that cases are dealt with expeditiously and fairly

Everything in modern dispute resolution flows from this overriding objective, whether or not the method chosen is litigation. Courts actively encourage parties to negotiate and mediate, where litigation would not be the most appropriate forum.

The upshot of the significant reforms to the civil justice regime through the Civil Procedure Act 1997, and to construction dispute resolution through the 1996 and 2009 Construction Acts, along with a shift in attitudes within the construction industry itself, is far greater choice when it comes to dispute resolution. This is partly pragmatic and partly a reaction to these statutory changes.

Alternative dispute resolution

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) – a generic term encompassing numerous different processes that allow for disputes to be settled outside of litigation and the court system – is actively encouraged under the CPR.

The most significant ADR processes are:

- negotiation – which may be structured to avoid a formal dispute, with an independent third party proposing an agreement that the parties may accept, or not

- mediation – which has long been encouraged by the Technology and Construction Court

- adjudication – referral to adjudication is now a statutory right under the Construction Acts

- arbitration – which is an adversarial process, with quite complicated rules set out in the Arbitration Act 1996. To some extent arbitration is perceived as a variation on litigation, rather than truly ‘alternative’, but it shares many positive features with other forms of ADR, such as the potential for time and cost savings.

The advantages, or otherwise, of ADR largely depend on whether the nature and quality of the decision or recommendation resulting from the process means that neither party decides to resort to litigation afterwards. ADR, even arbitration, will generally be cheaper than going through the litigation process to trial, but if the parties subsequently litigate the same dispute anyway, the costs will obviously be more than if they had simply gone to court in the first place.

ADR is usually quicker than litigation – a benefit of not being weighed down with 1,000 years’-worth of procedural law. The time and cost benefits, along with a number of other factors, also combine to make ‘collaborative’ ADR, such as mediation (as opposed to ‘adversarial arbitration or adjudication), less stressful for the parties involved; the process is typically less reliant on the participation of lawyers and will usually be confidential, and the parties may find it less difficult to maintain a working relationship during and at the end of the dispute.

Perhaps the one inevitability of a professional career is that it will involve differences of opinion with clients and fellow professionals from time to time, and that some of these differences may develop into disputes. Although the range of potential resolution processes available nowadays can seem bewildering, it must be better to have realistic alternatives for solving a problem more quickly and more cheaply than would have been possible in the past. As ever, the key is not to let a problem fester, but to seek professional legal advice at an early stage and to explore the options that now exist.

Do I need a solicitor?

Here, more than in any other aspect of an architect’s professional life it is vital to take independent legal advice. However experienced an architect is, they will benefit from legal assistance to guide them through any formal dispute resolution or disciplinary process. This is a counsel of perfection, and some architects will simply have no way of affording legal fees – but unfortunately experience shows that the results speak for themselves when professional parties try to defend themselves without legal representation.

It is almost always a false economy to risk losing a case because of an unwillingness to incur legal fees. A good lawyer can make the difference between winning and losing: they can find the persuasive argument that may otherwise have been missed. Where there is no winning argument, they can present the case in such a way as to make the fight more even. Perhaps the good lawyer’s greatest skill is to be able to tell an architect client when a case is not worth fighting.

10.3 Adjudication

Adjudication is a fast, relatively affordable, but adversarial dispute resolution procedure. Within a 28-day timescale, an adjudication produces a decision that is temporarily binding on the parties and enforceable by summary judgment in court. A losing party must generally pay up first before seeking to challenge the decision of the adjudicator in court proceedings or arbitration.

10.3.1 Adjudication under the 1996 and 2009 Construction Acts

Adjudication is the process that has dominated construction dispute resolution in the UK since it was introduced 20 years ago. Part II of the Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996 became law on 1 May 1998, bringing with it a regime for statutory adjudication, a new interpretation of a dispute resolution procedure that had been included as a contractual right in some construction contracts for many years previously. It is not possible for the parties to a construction contract, as defined by the Construction Acts, to prevent the Acts from applying to their contract.

Initial worries about adjudication – its ability to deal with all types of disputes, the possibility that its availability would increase the number of disputes, concerns about how to enforce adjudicators’ decisions – have largely fallen away. The success of statutory adjudication has been phenomenal.

Do the Construction Acts apply to my contract?

The Construction Acts apply, subject to some exceptions, to ‘construction contracts’, defined within the 1996 Act as contracts for the carrying out of ‘construction operations’. This is given a broad meaning and expressly includes consultancy appointments for architectural design and advice on building, engineering, interior or exterior decoration and landscape design.

A collateral warranty can in certain contexts be ‘a contract for the carrying out of construction operations’, as made clear in the Parkwood case noted in section 5.2.13 – so it can be possible, depending on the circumstances, for a beneficiary to refer a dispute to adjudication under a collateral warranty.

Importantly for architects, an appointment with a residential occupier concerning work or services for a dwelling house or flat is not within the scope of the Acts. Neither the payment provisions, nor the right to refer disputes to adjudication, will apply to the contractual relationship between an architect and such a residential occupier unless their appointment terms expressly incorporate the Construction Acts. If, for example, an architect contracts with a residential occupier on the basis of a standard form appointment such as the RIBA Standard PSC 2018 or the RIBA Domestic PSC 2018, each of which provide an option for adjudication, then this will be available to resolve disputes, and the applicable adjudication scheme will be either the Scheme for Construction Contracts, or the RIBA Adjudication Scheme for Consumer Contracts. But it is important that this possibility is explained by the architect to their client at the outset if the architect has proposed such an appointment. A court is likely to find that it is not otherwise fair to impose a binding, fast-track dispute resolution procedure (carrying a significant administrative burden) on a residential occupier who would otherwise be outside the scope of the Acts.

There is an extensive list of other works which are outside the definition of construction operations, and to which the Construction Acts therefore do not apply. An architect appointed to carry out services in relation to such works will not, in the absence of an appropriate contractual term, be able to refer disputes to statutory adjudication.

Finally architects should bear in mind that the Construction Acts apply not only to construction contracts that are in writing or evidenced in writing, but also to wholly or partly oral contracts. However, Act-compliant terms setting out the adjudication procedure do need to be included in the contract, and these need to be in writing; if they are not (as would inevitably be the case with any purely oral contract) the Scheme will apply.

10.3.2 The adjudication regime in theory ...

If a construction contract does not contain Act-compliant dispute resolution provisions, the Scheme for Construction Contracts (secondary legislation created to provide a practical framework for payment and adjudication where a contract does not) will be implied into the contract by law. If a construction contract contains a single provision that is not compliant with the Construction Acts’ adjudication regime then the Scheme provisions will apply in full, overriding even those parts of the contract disputes clauses that do comply with the Acts. This can be contrasted to the equivalent position when a construction contract does not contain Act-compliant payment provisions; in such a case, the relevant payment provisions of the Scheme are implied into the contract, but not in full – only to the extent necessary to fill in the gaps.

The Construction Acts give each party to a construction contract the right to refer disputes arising under the contract to adjudication at any time. Construction contracts must:

- allow the parties to give notice at any time of an intention to refer a dispute to adjudication

- provide a timetable for securing the appointment of an adjudicator and referral of the dispute to them within 7 days of the initial notice

- require the adjudicator to reach a decision within 28 days of the referral (not the notice) or a longer period agreed by the parties

- allow the adjudicator to extend the 28-day period by 14 days with the consent of the referring party (the claimant) – the responding party (the defendant) does not have a say in such an extension

- require the adjudicator to act impartially

- enable the adjudicator to take the initiative in ascertaining the facts and the law

- provide that unless they act in bad faith, or in bad faith omit to act, neither the adjudicator nor their employees or agents can be liable for any of their acts or omissions during the course of the adjudication.

The Acts also require a construction contract to provide that the adjudicator’s decision is binding on the parties until the dispute is finally determined by legal proceedings or arbitration; this is why adjudication is, in theory, only ‘temporarily’ binding. The parties may agree to accept the decision of the adjudicator as finally determining their dispute, and evidence suggests that all but a tiny percentage of adjudication decisions are the final word on the dispute in question, save for enforcement proceedings before a court.

10.3.3 ... and in practice

Instigating an adjudication

Whether you are considering making a referral to adjudication, or having to respond to a referral, there are a number of issues that have to be considered every time.

- Can it be said that there is a genuine dispute between the parties?

- Is your appointment a construction contract for the purposes of the Acts?

- Is your agreement one of those excluded from the operation of the Acts, for example because it has been made with a residential occupier?

- Are the rules for any adjudication set out in your appointment, or does the Scheme for Construction Contracts apply?

These are fundamentals. Adjudication will not be available in all cases, such as where there is no actual dispute or if the Acts do not apply to your appointment. If adjudication is available, the details of the rules under which the adjudication must be carried out can differ depending on the wording of your appointment. To make sure these fundamentals have been properly assessed in your case, it is very important to take specialist legal advice at the earliest possible stage.

If you are on the front foot, a solicitor will work with you to assess whether adjudication is available at all, and whether it is the right option in your circumstances. For example, what if you have had an instalment of fees withheld from you? The client may have followed the correct procedure for withholding, issuing the appropriate pay less notice and setting out the basis for not paying the notified sum in full, but what if you do not agree with the substance of the client’s reasons for paying less?

Adjudication should be seen as part of a process of escalation of pressure to achieve a satisfactory solution: Most architects are understandably cautious about instigating adjudication proceedings against a client, even if a solicitor has advised that adjudication may be possible. A solicitor will help you to decide whether any other options are available, and whether any other steps should be taken before getting to the point where a notice of intention to refer to adjudication is issued.

If you disagree with a pay less notice, make the client aware of your dissatisfaction. You may do this informally initially, at a meeting, but you should follow up your concerns in writing. Ask for clarification. Ask the client to reconsider, and provide additional information in support of your position if necessary. If you have other contacts at a higher level within the client organisation, raise the matter with them. If you have gone as far as you can commercially with your argument, to the highest level of contact you have within the client organisation, and still not achieved a satisfactory solution, a decision needs to be made. If the money withheld is important enough to you, it will be sensible to raise legal arguments, suggesting that if the client still does not agree to pay the money they have withheld, there will exist between you a dispute. Additional pressure can be applied by giving the client a deadline by which to respond one way or another. Most clients will recognise this as a threat that adjudication may be looming, but the threat could be made even more explicit if the client still refuses to compromise.

When can there be said to be a ‘dispute’? There have been a surprising number of cases concerned with when a dispute can be said to have ‘crystallised’, but each case turns on its own facts and it is hard to draw general principles. A common-sense approach is best. Simply saying ‘a dispute now exists between us’ will not be conclusive. But a client cannot be certain that a dispute has not crystallised if, for example, they repeatedly request vague ‘additional information’ as a tactic to give the impression that negotiations are ongoing and that they have not reached a final conclusion about the claim. Courts will typically take a purposive approach, giving the word ‘dispute’ its ordinarily understood meaning; sometimes it will be enough that the client has refused to admit the claim, or not paid it, even though the client has requested additional information.

It may be appropriate to increase pressure by having a solicitor send a letter to the client, formally making the same points and noting that a dispute now exists between the parties. Once a dispute exists, either party may give notice of their intention to refer the dispute to adjudication at any time.

Is it worth adjudicating? If adjudication has been explicitly threatened and the client remains unwilling to compromise, you will be faced with the choice of following through with the threat, or backing down. Will the costs involved in preparing a case for adjudication, and the costs of the adjudication itself, outweigh the sum that may potentially be recovered by adjudicating? The costs of preparing a case can be greatly reduced if your paperwork is already comprehensive and up to date. If it is not, you may need to spend significant sums just to get to the stage where you have sufficient material to put a convincing case before an adjudicator. It is often sensible, when all the work has been done to make a convincing case, to issue this to the client in a final notice before the notice to refer to adjudication, rather than ambushing the client, to give them a final chance to compromise before both parties incur the costs of an adjudication.

Another important factor to consider is the likely damage that will be done to the client relationship by adjudication. A non-confrontational procedure, such as mediation, may be a viable alternative; will a confrontational procedure achieve the best result? There is no guarantee of success in adjudication. The most sensible approach, before deciding to adjudicate, is to gradually escalate the dispute, through commercial and legal channels, and to consider at each stage the viability of making a referral.

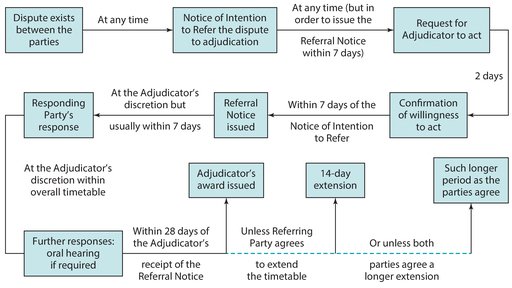

The course of an adjudication

If a dispute exists under a construction contract, notice of intention to refer the dispute to adjudication may be made at any time. A referral notice must follow within 7 days, and the decision will follow within 28 days of the referral notice (Figure 12). This can mean that the referring party has taken many months to prepare its case, but the time for the adjudicator to deliver their decision will generally still only be 28 days after the date of the referral notice.

Figure 12 Timeline diagram for the course of an adjudication

Since the 1996 Construction Act first came into force, there have been concerns about the potential for referring parties to ‘ambush’ responding parties, overwhelming them with technical and legal arguments that must be dealt with comprehensively in a formal response within a matter of days. The responding party cannot unilaterally extend the timetable for the adjudication, so the potential for ambush remains a real risk.

There can be no restriction on the right to give notice of intention to refer. It is even possible for a party to adjudicate a matter after it has issued proceedings in court concerning the same claim, although there has been one case (Phoenix Contracts v Central Building Contractors) in which a court decided that there could be exceptions to the statutory right and held that the referring party had waived its right to adjudicate because legal proceedings covering the same matter had reached an advanced stage. This is an exceptional decision, and seems unlikely to be followed in the light of previous judgments which have established that courts have jurisdiction to stay (prevent) court proceedings when a party exercises its right to adjudicate. Parties should work on the basis that if there is a statutory right, and there is a dispute, a notice of intention to refer to adjudication is possible at any time.

Appointment and referral: The Construction Acts contemplate the appointment of an adjudicator and referral of the dispute to them within 7 days of the adjudication notice. The parties may agree the identity of the adjudicator at this stage, or the adjudicator may have been named in the appointment. Often, the appointment will provide for an adjudication notice to be sent to an adjudicator nominating body – the RIBA is one such nominating body. Raising spurious objections to the identity of the adjudicator is rarely a successful delaying tactic for the responding party; most adjudicators take a robust approach and will rarely reject an appointment in the absence of a compelling argument as to why they personally should not take the matter on.

There are various standard terms of agreement for the appointment of an adjudicator, but many adjudicators also have their own standard terms. Either way, the adjudicator will want both parties to agree the terms of their appointment at the outset of an adjudication. That said, an adjudicator will generally never allow the timetable to slip because one party (usually the responding party expressing displeasure with the process) has not signed their appointment. The adjudicator will generally want at least one party to actually agree in writing to payment of their fees and expenses before proceeding, and it is obviously in the interests of the referring party to do this. The underlying contract or appointment will usually make both referring party and responding party ‘jointly and severally’ liable for the adjudicator’s fees. This means that the adjudicator may recover the whole of their fees and expenses from either party; if one party refuses to pay their share, the paying party is left to take further legal action to recover a contribution from the non-paying party.

The referral notice must be limited in scope to the dispute identified in the original adjudication notice, but should contain all the relevant details, evidence, witness statements and copies of contractual documentation that the referring party needs to rely on to make its case. Here is where the concern over ‘ambush’ of the responding party originates; only one dispute may be referred in any one adjudication, but the referral may be a lengthy document, setting out many heads of claim within the single dispute, and the accompanying documentation can often amount to several lever arch files.

Once the adjudicator receives the referral, they will give directions for the future conduct of the adjudication, including timing for delivery of the response to the referral and any other rounds of communication that may be allowed. The adjudicator will typically allow communication by email, for speed, but it is good practice to follow up emailed documents with copies by fax or post. The adjudicator will very often require the response to be served within a very short period; this puts the responding party at a disadvantage if the referral notice documentation is particularly bulky or contains a good deal of material that the responding party has not seen before.

The response and further replies: The various sets of available adjudication rules (as well as the Scheme for Construction Contracts, a number of construction industry bodies have produced Act-compliant standard rules, and there also exist amended and bespoke versions) provide for the adjudicator to dictate the timetable within the 28-day adjudication period; that includes setting a date for the defendant to serve their response to the referral notice. Often the timing will be tight, with a response required by the adjudicator within 7 days of the referral notice. In extreme cases, this can raise issues of natural justice, if it can be argued that the defendant is being denied a fair chance to construct their defence.

In the case of CJP Builders v Verry the adjudicator misdirected himself when approached by the defendant who sought an extension of time for serving their response to the referral notice. The applicable rules in that case would have allowed the adjudicator to grant the extension requested without reference to the referring party, but the adjudicator decided he had no discretion to grant the responding party’s extension without the referring party’s agreement.

The referring party agreed only to a shorter extension of time, and the responding party just failed to serve their response in time. The adjudicator refused to consider the response, and subsequently made an award in favour of the referring party. The court decided that the adjudicator had breached the rules of natural justice by effectively denying the defendant’s right to be heard, and as a result his decision was unenforceable. This result may give encouragement to parties seeking extensions of time within the adjudication timetable, although an extension cannot be allowed to interfere with the delivery by the adjudicator of their decision.

Contents of the response and the responding party’s tactics: The defendant’s response should fully address all the arguments raised by the referring party, and should contain all the material the defendant needs to rely on to show that the referring party’s claim should not succeed. It is not wise for the defendant to refuse to take part in the adjudication, even if they consider the claim to be obviously invalid. Any challenges to the fundamentals of the process, most usually to the adjudicator’s jurisdiction, should be made early and repeated as necessary throughout the course of the adjudication.

The best course of action for the defendant is to produce a substantive response to the claim as well as raising any possible jurisdictional issues. The defendant should participate in the process, but reserve their position in relation to the jurisdictional issues; this will allow them to raise the same arguments about the adjudicator’s lack of jurisdiction in response to any proceedings brought by the referring party to enforce a decision in their favour. There is always a possibility, too, if the responding party raises a valid jurisdictional argument early on in the process, that the adjudicator will decide that they are not able to continue to deal with the matter, and all parties could be saved a good deal of time and money.

Further replies and the likelihood of a hearing: The adjudicator is likely to allow the referring party a reply, and may grudgingly allow further replies if the parties can demonstrate that there is something new that needs to be replied to in the interests of justice. The adjudicator may direct that an oral hearing should be held, particularly if there is a factual dispute (rather than one involving the interpretation of documents) at the heart of the adjudication, and especially if a number of witness statements have been served with the referral and the response – the adjudicator may well be interested to see how well the various witnesses come across in person. At some stage the adjudicator may also seek specific responses from both parties to particular questions – these may be issued in a list and may give a hint as to the adjudicator’s thinking about the matter as a whole.

The adjudicator’s decision: There is no prescribed form for an adjudicator’s decision. The Scheme requires that it should be given in writing, and it is sensible to request that the adjudicator gives reasons in their decision. Decisions delivered outside the 28-day period (or any longer period agreed) are very likely to be unenforceable if the losing party takes the point during enforcement proceedings.

10.3.4 Enforcement, and resisting enforcement, of an adjudicator's decision

If the losing party does not voluntarily comply with the decision, an adjudicator’s award may be enforced through the courts by summary judgment. This is a fast-track litigation procedure, based on the claimant’s application notice (accompanied by a supporting statement) appropriate for cases where the court considers that the defendant has no real prospect of successfully defending the claim. A short hearing is involved; the court will give summary judgment if there is no other compelling reason why a full trial should be held.

In theory, the losing party is in a position where, even if they disagree with the award, they must pay up first and argue about the detail later, by bringing their own case to court to re-argue the points unfavourably dealt with by the adjudicator. In practice, losing parties often try to avoid paying up by challenging the validity of the decision during the winning party’s enforcement proceedings. Even so, as will be seen below, the courts remain extremely reluctant to refuse to enforce an adjudicator’s award in all but the most extreme cases.

The approach of the courts to enforcement

In order to give effect to the intention of Parliament and create a regime under the Construction Acts where an aggrieved party could take action quickly and cheaply to recover money owed to it, the courts have tended to take an extremely robust approach towards the enforcement of adjudication decisions. All other things being equal, as long as the adjudicator has provided a decision within the statutory timescale that provides an answer to the issues raised in the notice of adjudication, a court will enforce the adjudicator’s decision. This remains the case even where the decision is patently incorrect, in law, procedure or fact. This principle was set out in the very first statutory adjudication case that came to court, Macob Civil Engineering v Morrison Construction Ltd.

If the adjudicator gives the wrong answer to the right question, there is generally nothing that the losing party can do to prevent enforcement. This can work in favour of architects who, along with contractors and subcontractors, appear far more regularly as the referring party in adjudications than as the responding party.

Can a losing party ever successfully challenge enforcement?

If the winning party is in financial difficulties and it is arguably unlikely that the losing party will be able to recover their money later through court proceedings, this will not automatically make any difference – the loser must still pay. Courts have indicated that they will enforce an adjudicator’s decision even in favour of a party who has entered into a company voluntary agreement – a binding agreement made between a company with severe financial problems and its creditors, setting out the amounts to be repaid by the debtor company. This might at first glance seem unfair to the paying party, but the courts are looking to protect the position of a winning party whose financial problems may have resulted from the paying party’s original failure to pay fees due, in breach of contract.

Successful challenges are possible, generally on two grounds only:

- a lack of jurisdiction to make the decision, on the part of the adjudicator, or

- a breach of natural justice.

However, the courts have set the thresholds extremely high, particularly in relation to breaches of natural justice; even the most blatant errors in procedure have not prevented enforcement of a decision that gives an answer to the issues contained in the adjudication notice. A rare example of a successful challenge on the basis of a breach of natural justice is the CJP Builders v Verry case, mentioned above, where the losing party was denied the opportunity to have their defence heard because of a procedural error by the adjudicator. Recent cases have also seen defences to enforcement proceedings on the basis that the adjudicators’ decisions had been obtained by fraud; these arguments have not been successful, and the threshold for proving fraud in these circumstances is again extremely high.

It has been possible to achieve a partial stay on enforcement proceedings (the court refusing to support enforcement of the whole of the adjudicator’s award – for now) on the basis of potential ‘manifest injustice’, although the court In the case of Galliford Try Building v Estura Ltd [2015] EWHC 412 (TCC) said that its reasoning would be appropriate only in rare cases. The facts of the Estura case strongly suggested that if the adjudicator’s award was enforced in full, the paying employer would be denied the opportunity to reassess the valuation of the works at final account stage, because the contractor would no longer have any incentive to operate the final account mechanics.

Adjudicators cannot (in contrast to arbitrators, for example) give a binding decision on their own jurisdiction, and jurisdictional challenges have been a constant feature of defences to enforcement proceedings since the 1996 Construction Act first came into force. An aggrieved party may claim, for example, that the adjudicator’s appointment is defective; that the adjudicator has answered a question not referred to them; that there was no actual ‘dispute’; or that there was no written contract, or at least not a construction contract for the purposes of the Acts.

The High Court and Court of Appeal have repeatedly taken a dim view of losing parties, as they see it:

(This quote is taken from the judgment in Carillion v Devonport Royal Dockyard ). For the most part the courts will, even in cases where they recognise that a technicality could invalidate an adjudicator’s decision find that the technical or theoretical breach did not, on the specific facts of the case, take place.

In summary, the ‘pay now, argue later’ principle, which Parliament intended to enshrine in the adjudication provisions of the 1996 Act, is working well with the support of the courts. This suits architects, and is to the disadvantage of the paying party on any appointment to which the Construction Acts apply. Even if in a particular case there has been a breach of natural justice or a lack of jurisdiction, a court will continue to do its utmost to enforce any ‘unaffected’ part of the adjudicator’s decision by severing out the unenforceable elements, as for example in the case of Cantillon v Urvasco Limited.

There is nothing to stop a losing party (once it has paid up) from commencing an action in the High Court to have the original dispute finally determined – bear in mind that adjudication was only ever intended to be temporarily binding, until finally determined by court action or arbitration (depending on which method is provided for in the underlying contract). Parties wishing to seek final determination should make sure that they do so promptly. In the 2015 Supreme Court case of Higgins v Aspect it was decided that a party could not raise counterclaims relating to alleged defective performance during the original works because the time for raising such actions under the contract in question had expired – in this case, the relevant limitation period was 6 years from the date of the alleged breach. The party wishing to enforce its adjudication award was not similarly limited in their ability to enforce the award – the court decided that the failure of the losing party to pay the sum stated in the award was an independent breach of contract, and a second limitation period began to run from that point, a point much later in time.

10.3.5 Ongoing issues for architects with statutory adjudication

Adjudication, if available under the appointment, is a useful tool for an architect. The possibility of an adjudication will help to concentrate the mind of a client who would otherwise not think twice before withholding fees. But although adjudication is relatively inexpensive (certainly compared with litigation, at least in former times) costs are still an issue. It is very hard for the referring party to frame their adjudication notice so narrowly that the responding party is severely restricted in terms of the material they may include in their response – the courts take a liberal approach to the material a responding party can introduce anyway – and the more complicated the adjudication becomes, the more expensive it will inevitably become. As well as increasing the cost, a failure to prepare for an adjudication with a wide scope can damage the referring party’s chances of success.

The main problem is that, in contrast to litigation for example, statutory adjudication does not provide a mechanism for the recovery by the winning party of their costs; the costs of an adjudication can only be awarded where such a provision has been made between the parties in writing. The case of Enviroflow Management Ltd v Redhill Works (Nottingham) Ltd (unreported, TCC 16 August 2017) stated clearly that such a term cannot be implied; it must be in writing, and without it costs may not be awarded by the adjudicator.

As a result, it is rarely commercially viable for a party to pursue adjudication, even if there is a very good chance of the claim being successful, for sums less than £10,000 to £15,000. Towards the end of a project an unscrupulous client may be encouraged to withhold relatively small sums, a few thousand here and there, without justification while remembering to serve the appropriate notices, safe in the knowledge that the architect will have limited options for recovery of these sums. Commencing an action in the small claims track of the county court may be an option to recover sums less than £10,000, but in reality if the client raises a plausible defence involving more than minor legal argument, the case is unlikely to remain on the small claims track and legal costs may escalate to a point where continuing the claim becomes economically unviable.

One final point for the architect to bear in mind – it is never appropriate to take conduct of an adjudication on behalf of a client, or to agree as an additional service to draft or review an adjudication response or any other adjudication ‘pleadings’. Client requests to do so should be politely refused; these are specialist legal tasks. Assistance with claims can be provided, as an additional service and for an additional fee, but should be limited to commenting on matters of fact or technical issues directly relating to the architect’s own services.

10.3.6 Adjudication after the 2009 Construction Act

Contracts in writing

The 2009 Construction Act expanded somewhat the scope of application of statutory adjudication, most notably by removing the requirement for a construction contract to be in writing, or evidenced in writing, as a pre-condition for the availability of statutory adjudication. This change was a positive one – it would be unfortunate for parties to be denied justice solely by reason of their administrative failure to put in place a written agreement – but bringing oral contracts within the scope of statutory adjudication has also created concerns. If there is no need for any contractual terms to be in writing, there is a greater prospect of more adjudications becoming focused on what exactly the contract terms are – a task that is not best suited to a summary procedure such as adjudication. The inevitable need for an adjudicator to hear oral evidence, about who agreed which contractual terms, can lead to increases in adjudication costs. The need for oral evidence can also delay the process, despite the fundamental requirement for a decision within 28 days of the referral. Another reasonable criticism is that one strong incentive for agreeing written contract terms – surely best practice – has been undermined.

Other changes

The 2009 Act brought two other important changes to the statutory adjudication regime. The first was the formalisation of the ability of the adjudicator to correct their decision so as to remove any clerical or typographical errors arising by accident or omission. This so-called ‘slip rule’ was assumed to be available to adjudicators anyway, following the case of Bloor Construction (UK) Ltd v Bowmer & Kirkland (London) Ltd, but the 2009 Act removes any doubt about the legitimacy of this procedure. The time allowed for correcting slips may be assumed (this is not set out expressly in the 2009 Act) to be a ‘reasonable’ period following delivery of the adjudicator’s decision, but this does raise the question of what period is reasonable. There may also be challenges to decisions based on the scope of the corrections that an adjudicator may have made, or refused to make. It seems likely that some parties will try to exploit the slip rule to seek ‘corrections’ of fundamental decisions of fact or law, or it may be argued by a losing party that the adjudicator has exceeded their jurisdiction in correcting a slip.

The last important change brought in by the 2009 Act was the long-overdue prohibition of contract provisions making one party (usually the referring party) solely responsible for the costs of any adjudication; these clauses became known as ‘Tolent clauses’, after the case which first highlighted the problem. Such provisions were always an unfair disincentive, effectively a fetter on a party’s right to refer disputes to adjudication at any time, and at odds with the spirit of the original Act. This has been recognised by the courts already – in Yuanda (UK) Ltd v WW Gear Construction Ltd the court decided that such a provision was in conflict with the original 1996 Act – so Parliament was right to formalise the law on this point. Because architects are far more often the referring party than the responding party in adjudications, they benefit from this change, along with other professional consultants and specialist subcontractors.

10.4 Arbitration

The parties to a commercial contract may choose to have disputes resolved by arbitration, as an alternative to litigation. Arbitration is an adversarial process which produces a binding award that may be enforced by the winning party on application to a court. There are very limited grounds on which an award may be appealed against or set aside. The arbitration process mirrors to an extent the other available adversarial procedures (litigation and adjudication).

- There is an initial notice.

- The parties state their cases and disclose the evidence on which they intend to rely.

- There is a hearing of the case.

- The arbitrator makes an award.

Arbitration in England and Wales, including procedural aspects, is governed by the Arbitration Act 1996 (AA 1996).

An arbitration can only take place between two parties if they have agreed to it; the right to arbitrate, the identity of the arbitrator, and the procedure to be followed during the arbitration are all in the hands of the parties. Under a construction contract, the dispute resolution procedures available by default are adjudication and litigation. The parties have to make a positive decision to choose arbitration.

Architects should always seek legal advice before instigating or responding to arbitration proceedings, or in relation to any other involvement in the process, for example as a witness.

10.4.1 Why choose arbitration?

Arbitration is a sensible choice in a project with an international dimension. Sometimes there may be doubts about the standard of the local legal system, in which case the ability to refer disputes to trusted, independent and experienced international arbitrators is reassuring. If one of the parties to the contract is based overseas there is also an advantage – surprisingly, in a foreign country it can be far easier to enforce an arbitrator’s award than the judgment of an English court. To date, 156 of the 193 member states recognised by the United Nations are signatories to the 1958 New York Convention on the enforcement of foreign arbitration awards.

10.4.2 Positive features of arbitration

The AA 1996 gives arbitrators a good degree of freedom to be flexible about the procedure to be adopted in any given arbitration, and when used creatively an arbitrator has the ability, through the AA 1996, to deliver high-quality justice quickly and cheaply, without an over-emphasis on procedural issues. It is questionable whether the current crop of arbitrators are making the most of the opportunities provided by the AA 1996 to provide such a service, and for domestic projects, adjudication and litigation remain the default choices.

The approach of the parties, and the choice of arbitrator, are crucial. The arbitrator has greater flexibility over the procedure to be followed than either the adjudicator in adjudication or the judge in litigation. Whether the parties to a contract receive the potential advantages of the arbitration process is to a large degree dependent on their behaviour, and on the performance of the arbitrator.

Of prime importance to most participants in the process are quality, time and cost. The parties to an arbitration are free to choose their own arbitrator, so the arbitrator may be selected because of a specific technical expertise which is relevant to the case, going some way to ensuring a better quality of decision. The time taken over the decision-making process can enhance quality too, certainly in comparison with adjudication, which is acknowledged to be a ‘rough and ready’ procedure.

Generally, the arbitration process will be longer than an adjudication, in theory allowing for an enhanced quality of justice; but arbitration is usually a quicker process than litigation because the procedural rules are less prescriptive, and the parties and the arbitrator are largely free to decide what the procedure will be and what the timescale will be. There is nothing in the AA 1996 that would prevent an arbitration from being conducted within the 28-day time period of an adjudication, or indeed any shorter period. The quicker the process is, the less it is likely to cost, and arbitration typically strikes a middle ground between adjudication and litigation in terms of the overall cost.

One other aspect of arbitration that helps to reduce costs is that in most cases the parties will only produce as evidence the documents on which they intend to rely; contrast this with the ‘disclosure’ process in litigation, where the parties are obliged to provide huge numbers of documents, both favourable and unfavourable to their cases, at an early stage in the process. The legal fees incurred by lawyers in obtaining and reviewing disclosed documents during litigation can be huge.

The arbitrator has the power to award costs as part of their final decision. The general rule is that the loser pays, unless there is evidence as to why the costs should be allocated differently; for example, if the loser made a realistic offer to settle earlier in the process that was rejected by the winning party.

Arbitration is a private process, and the proceedings are confidential. If parties are keen to avoid damaging public revelations, arbitration offers this benefit, but this is an advantage shared by all procedures other than litigation. Finally, the parties may be keen to have a ‘once and for all’ decision made about their dispute, and arbitration allows the parties to agree that any right of appeal is waived. This is really only an advantage if you get the right decision.

10.4.3 Disadvantages of arbitration

A perception of arbitration is that it is probably best suited to complex, high-profile, high-value disputes with an international dimension – where ensuring a high-quality final decision, privacy and ease of enforcement are the most serious issues. Yet one of the major disadvantages of arbitration is that the arbitrator has no power to order that other parties should be ‘joined’ into the original dispute if they have connected disputes with one of the original parties. It is not uncommon for multiple parties to be involved in high-value construction disputes, and arbitration is not set up to deal with that possibility, potentially leading to several overlapping arbitrations taking place at the same time, with the potential for increased costs and inconsistent decisions.

Other disadvantages of arbitration are the flipsides of the potentia advantages. The procedural rules can be applied flexibly, but the arbitrator does not have the same powers as a court to insist on compliance with the rules and deadlines they set out. The arbitrator may be a specialist in the particular technical areas with which the case is concerned; but if the case turns on a legal issue, the parties would have been better served by a judge. Timing, and consequently costs, are not necessarily going to be an improvement on litigation if the parties do not co-operate and the arbitrator is not sufficiently strong.

The parties to an arbitration must also bear in mind one significant cost that is never an issue in litigation – the arbitrator’s own fees, which may be considerable. The parties will still be paying legal costs in the same way as they would in an adjudication or litigation.

Finally, what of the quality of the decision? The disclosure process in litigation is often very expensive, but the advantage is that a party cannot easily hide documents that are damaging to its case. The absence of full disclosure could easily mean the difference between winning and losing a case.

It is arguable that the AA 1996, while providing a great deal of procedural flexibility, is simply not prescriptive enough. The stakes involved in the sort of technically complex, high-value cases that would otherwise be suitable for arbitration are too high for many parties to feel comfortable with accepting the relative uncertainty of the arbitration process.

10.5 Litigation

10.5.1 Why choose to litigate?

Litigation is an adversarial dispute resolution process involving a trial that is open to the public and that leads to the judgment of a court. Parties may choose to negotiate or mediate, or there may be a referral to adjudication, but in the background will usually be the potential for litigation to finally decide a dispute; parties would need a particular reason to choose arbitration as the fallback position rather than litigation. Even so, it is far more rare for a dispute to be the subject of litigation than, say, adjudication.

The procedure adopted in litigation is decided by the judge on the basis of their application of the Civil Procedure Rules (CPR). The judgment is final and binding, subject to a right of appeal to a higher court. Parties who choose litigation can expect a high quality of justice delivered by judges of the Technology and Construction Court (TCC), who are among the very best in the world. However, it is also well known that litigation can involve costs out of all proportion to the sums in dispute and may take years to reach a conclusion.

Whether as claimant, defendant or witness, you should never engage in the litigation process before seeking legal advice. Some disputes, if particularly high value or legally complex, may seem obvious candidates for litigation rather than, for example, adjudication. But generally litigation is best viewed as the last option for a dispute that cannot be settled in another way. There is no construction dispute whose subject matter would be too complex for the TCC; but choosing to litigate a low-value dispute is not wise. The court may decide that a party who proceeds with litigation when other, cheaper alternatives may have been more appropriate should be unable to recover its legal costs in full, even if successful.

10.5.2 How does litigation work in practice?

In construction disputes, before an action can be commenced in court, the parties are obliged by the CPR to comply with the Pre-Action Protocol for Construction and Engineering Disputes (the Protocol) (Figure 13). Parties who fail to comply with the Protocol and launch straight into litigation are likely to be punished in costs by the court if the matter proceeds to trial. The Protocol applies to all construction disputes, specifically including ‘professional negligence claims against architects’ (Protocol paragraph 1.1). Some actions are exempt from the application of the Protocol, for example actions to enforce an adjudicator’s decision.

Figure 13 Pre-Action Protocol for Construction and Engineering Disputes

The Protocol sets out a mechanism for the parties to provide information about their respective cases that is as full as possible, as soon as possible. The idea is to save the parties’ costs; with early access to all the relevant information, parties are in a better position to assess the strength of their own cases and decide whether it is worth carrying on with the fight, and in this way it is hoped that many cases will settle early. Unfortunately, the side effect of compliance with the Protocol is that parties are obliged to spend significant sums of money right at the start of the litigation process to develop their cases.

Building your case

During this initial phase and throughout, the architect should work closely with their solicitors. They should not be tempted to hold information back; there is nothing to be gained by giving the false impression, to the architect’s own legal advisors, that their case is stronger than it really is. Adopting such an approach is likely to lead to significant sums of money being wasted in the long term.

There will generally be a good deal of correspondence before a claim begins to become formalised, but the first Protocol requirement is that the claimant sends a letter of claim, setting out a brief summary of their claim and in broad terms what they are seeking – usually damages. The defendant is given a set time to respond with a letter detailing their own position, and following this exchange the Protocol timetable provides for a pre-action meeting to narrow the issues. At this stage, paragraph 9.3 of the Protocol explicitly requires the parties to:

Commencement of the action, through to trial

An action is said to be ‘commenced’ (for the purpose of statutory or contractual limitation periods on bringing actions) when the claimant issues a claim form in the court. The claim form is then served on the defendant, along with a document setting out the particulars of the claim, within a period set by the CPR. After this, the defendant will file an acknowledgement of service, and then a formal defence to the claim, along with any counterclaim it may wish to make. Parties will typically be advised at this stage, if not before, that it is necessary to engage a barrister (counsel) to advise on the content of the documents lodged with the court; it will be counsel’s role to present their party’s case before the court at trial and in the various pre-trial hearings, such as the case management conference discussed below.

A judge will have been assigned to the case at the outset and at this point the judge will require a case management conference – a short hearing in court – to settle the timing and procedure of the case up to trial. The judge issues directions to the parties covering such issues as the disclosure of relevant documents, exchange of witness statements, the preparation of the bundle of papers to be used and referred to in court during the trial, and the date of the trial itself. Prior to trial the judge will require a pre-trial review hearing and, if no settlement can be reached, the case proceeds to trial on the appointed day or days, followed by the judgment of the court. The vast majority of cases settle before this point. Legal fees for solicitors and counsel over the course of a trial can be very significant.

10.5.3 How litigation is changing to reduce costs

The overriding objective of litigation under the CPR is to deal with cases justly, and that requires ‘proportionality’ – the costs involved in litigation must be proportionate to the value of the case to the parties. But it is surprising how often litigation seems to take on a life of its own and parties seem unable to break out of the process. A solicitor should always be able to advise you if you are in danger of throwing good money after bad. If a solicitor advises compromise or settlement, this advice should be taken at face value – it is a matter of professional competence for a solicitor not to encourage a client to waste money by pursuing a cause with only a slim chance of success.

Even with the support of good legal advice, litigation can be a painful and unpredictable process and, bearing in mind the financial costs and management time involved, is best avoided if at all possible. The Jackson Report (Review of Civil Litigation Costs: Final Report, 14 January 2010 proposed changes to the system to better limit the costs of litigation. It was clear the courts were concerned that some parties were prevented from seeking justice (or from properly defending themselves) because of the continuing and well-rehearsed criticisms of civil litigation – the procedures are too complex, the process takes too long, litigation is consequently too expensive, and as a result is financially too risky for the participants. The Jackson Report was aimed at promoting access to justice, because parties, particularly in the construction industry, were (and continue to be) increasingly looking to alternative means to resolve disputes. In practice this means adjudication, which, although intended to be only temporarily binding, is in the vast majority of cases the last word on the dispute. Parties do not relish the prospect of fighting their case again in court if they have lost an adjudication.

The government agreed to implement the vast majority of the reforms proposed in the Jackson Report, and most of the relevant provisions came into force on 1 April 2013. Still for most cases for most architects, litigation is not the most appropriate option, even if it is commercially viable.

10.6 Mediation

The most popular and effective dispute resolution mechanism is negotiation. The term ‘mediation’ covers a broad range of approaches, but at its most fundamental level mediation is simply negotiation conducted through, and given structure by, an independent third party. Mediation is a consensual process, not a confrontational or adversarial process like litigation, adjudication or arbitration. The outcome is largely down to the parties; no binding award can be imposed on them without their consent. However, if the parties agree that the mediation settlement is to be framed as a contract, it may be enforced through legal proceedings in just the same way as any other binding contract. Only at this point does the process become binding on the parties.

Mediation had been available as an option in the UK since 1990 and the arrival in London of the Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution (CEDR), but its popularity has steadily increased since it officially became part of the litigation process when the CPR came into force in 1999. If the parties to a contract take their dispute to court, the court will almost always encourage them to make a genuine attempt to settle their differences through mediation; a party is likely to suffer costs consequences at the hands of the court if they fail for no good reason to engage with some form of alternative dispute resolution process and simply plough ahead with litigation. In this sense mediation is less ‘voluntary’ than it used to be.

Many other parties elect to mediate even without this encouragement, in an effort to preserve working relations in spite of the dispute, and avoid resorting to a confrontational dispute resolution procedure. Most standard form contracts provide for mediation as an option, rather than as something that must be pursued. The RIBA Standard PSC provides in clause 9.1 that the parties may attempt to settle any dispute or difference ‘by negotiation or mediation, if suitable’. Any construction dispute, however complex, may potentially be suitable for resolution through mediation if the parties are willing to make the process work. More detailed information about the mediation process and tactics for a successful mediation can be found in the RIBA’s Good Practice Guide: Mediation (2009).

10.6.1 How does mediation work?

The mediator’s role will vary according to the requirements of the parties. In some cases they are required only to give structure to the discussions; in other cases they are required to give their opinion on the merits, either of the case as a whole or some particular aspect or aspects of it.

Mediation is private and confidential, and will always be conducted on a ‘without prejudice’ basis – meaning that if the mediation fails, details (such as any offers to settle, or other concessions or admissions) cannot be released to any subsequent tribunal, be it a court, arbitrator or adjudicator. The parties will need to have agreed to mediate before it can happen; the details of how the mediation will be conducted and who will act as mediator can be hard-fought negotiations in themselves.

Once the details are agreed, a formal mediation agreement (made between the parties and the mediator) is usual, providing among other things for confidentiality and preventing the parties from calling the mediator as a witness in any future proceedings. The process is then relatively quick and cheap. To be effective, the parties should prepare thoroughly, and parties should generally be accompanied at the mediation by their legal representatives, but there are important cost savings to be made if the mediation produces a settlement and the parties avoid having to engage in a confrontational dispute resolution procedure. The parties’ working relationship may also be preserved.

When is the right time to mediate?

There is a balance to be struck. The sooner the parties submit to mediation, the greater are the potential cost savings. However, if the parties have not developed their cases thoroughly enough before mediating, the effectiveness of the mediation will be limited. The parties will not have a sufficiently strong grasp of the strengths and weaknesses of their cases to know when a good settlement is being proposed.

Prior to the mediation, it is common for the mediator to ask for written statements of the parties’ respective positions, along with key documents, to enable the mediator to understand the background to the dispute. On the day, or days, of the mediation, there may be an initial meeting of the parties and mediator together, during which the parties state their cases and the mediator looks for areas of compromise. The open-session format may continue, or the parties may break out into separate rooms and conduct the mediation through the mediator carrying out ‘shuttle diplomacy’; in such circumstances, the mediator will only be allowed to pass on to one party information given to them in confidence by the other if they are specifically given permission to do so. The skill of the mediator is to focus the thinking of the parties and suggest areas for compromise.

10.6.2 Advantages of mediation

Speed and cost efficiency are the two main advantages of a successful mediation; mediations normally last no longer than 2 to 3 days. There is also evidence (in The Fourth Mediation Audit by CEDR, 11 May 2010) to suggest that the settlement rate is very high, with up to 75% of cases settling ‘on the day’ and a further 14% settling shortly afterwards. There is, though, word-of-mouth evidence to suggest that as the number of mediations overall has increased, the settlement rate has been decreasing.

Is there still an advantage in mediating, even if a settlement is not achieved? It is hard to argue against the logic of taking a chance on mediation, in spite of the additional cost, because the benefits if successful are potentially so great. Particularly if a court has suggested that the parties attempt mediation, there is no advantage in refusing to try. And even if a settlement is not reached, it is likely that the mediation process will have focused the thinking of the parties on the most important areas of difference between them and will in all likelihood save costs and lead to a settlement sooner than may otherwise have been the case.

10.6.3 Disadvantages of mediation

As mediation becomes part of the normal litigation process in every case, it is likely that there will be an increasing number of unwilling parties to mediations, which seems likely to affect the success rate and also lead to more (and more creative) legal challenges to mediation agreements. Such challenges may serve to undermine some of the basic principles of mediation, for example confidentiality. In the case of Farm Assist v DEFRA the court made clear that what parties do or say in a mediation will not necessarily remain confidential if it is ‘in the interests of justice’ for a court to be told the details.

One further issue is the additional cost of an unsuccessful mediation. This may not be a huge amount in the grand scheme of complex litigation that goes to a full trial, but if it is obvious that one or other party is unwilling to compromise and is simply going through the motions, the money spent on mediating is being thrown away. Compromise is always a necessary element of a mediation settlement. This presents another potential disadvantage – a party with a very strong case may be presented with a settlement that is below their level of expectations, but may feel compelled to agree it rather than risk incurring further legal costs by taking their case through an adversarial dispute resolution process. There is no guarantee that reasonableness will be rewarded; the success or otherwise of a mediation is largely dependent on the attitude of the parties.

Chapter summary

- The RIBA may bring disciplinary proceedings against its members and the ARB may bring disciplinary proceedings against any architect for breaches of their respective codes.

- Any architects faced with disciplinary proceedings should engage fully with the process and take formal legal advice as appropriate in order to defend themselves.

- Disputes may arise and affect even the best-run practices.

- The four key dispute resolution methods in the construction industry are adjudication, litigation, arbitration and ‘alternative dispute resolution’, which includes negotiation and mediation.

- Dispute prevention is better than dispute resolution, but in the event of a claim an architect should seek formal legal advice and engage with its insurers.