Chapter 5

Capital Structure and Risk in Islamic Financial Services

1. INTRODUCTION

In general, the role of equity capital in firms is to absorb unexpected losses, expected losses being covered by provisions that are liabilities. In addition to equity capital, other forms of financial instruments may serve to absorb losses, notably preferred shares and convertible or subordinated debt. The essential role of such capital is the protection of creditors of the firm, making it creditworthy or solvent.

The capital structure of financial services firms such as banks and insurance undertakings, and in particular the proportion of equity capital in their capital structure, is subject to regulation, with particular reference to its ability to absorb losses without these being passed on to depositors (in the case of banks) and policyholders (in the case of insurance undertakings). “Capital adequacy” of banks is a key concern of regulators and supervisors in view of the systemic risk of contagion within the banking sector; if depositors lose confidence in the solvency of one institution and withdraw their funds, this tends to have “knock-on” effects on other banks, which can result in a banking crisis such as that experienced following the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. (The failure of Lehman Brothers, however, was symptomatic rather than a cause of that crisis.)

In the case of insurance undertakings, there is not the same exposure to withdrawals of deposits as there are in banks, but in addition to the concern for policyholder protection there is a risk of cross-sectoral knock-on effects—for example, where banks hold credit default swaps issued by an insurance undertaking that is unable to honour them (as in the case of AIG in 2008).

The more risky the assets held by a firm, the more “risk absorbent” capital it requires to remain solvent. Hence, the regulatory regimes for banks and insurance undertakings typically take account of the riskiness of their assets in determining their capital requirements. In the case of banks, the Basel Accords employ “risk weightings” of assets. Insurance undertakings and their supervisors also need to consider the riskiness, or susceptibility to estimation error, of insurance liabilities (technical provisions), as in the European Union’s risk-based capital regime known as Solvency II (see Smith 2009).

Both Islamic banks and Islamic insurance (takaful) undertakings have, in their different ways, specific characteristics as regards both asset risk and capital structure, which differentiate them from their conventional counterparts. It is these characteristics and their implications that form the subject matter of this chapter. Section 2 concerns Islamic banks, while Section 3 addresses takaful undertakings. The final section sets out some concluding remarks.

2. RISK AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE IN ISLAMIC BANKS

Asset risk in Islamic banks differs from that in conventional banks because the assets held by the former comply with Shari’ah requirements to avoid interest, and also because some of the risk management (hedging) tools used by conventional banks do not meet Shari’ah requirements. Thus, Islamic financing assets are based on (a) exchange transactions involving non-financial assets, (b) forms of leasing contracts, or (c) forms of partnership. These forms of contract allow the Islamic bank to earn an interest-free return on funds. They also entail, to varying degrees, asset or market risk associated with the assets involved in the exchange or leasing contracts, or the particular form of credit risk arising from the provision of financing on a partnership basis (where the financier has no debt claim on the party being financed). In addition, Islamic banks are exposed to specific forms of operational risk. Consequently, Islamic banks need to hold capital against these market risks and operational risks.

2.1 Market Risk Exposures on Islamic Financing Contracts

Different types of market risk exposures have varying effects. This section examines examples from Islamic financing contracts involving exchange transactions, lease-to-buy contracts, and partnerships.

Exchange Transactions

Examples of market risk exposures resulting from exchange transactions in the course of Islamic financing contracts are given below. These exposures may be mitigated in various ways, but subject to that they give rise to a need for capital as set out in the Basel 1996 Market Risk Amendment.

Murabahah Financing

The murabahah contract is used in credit sale transactions, in which the bank acquires ownership of the asset which its customer wishes to buy and then sells it to the customer on credit. Prior to the credit risk exposure following the sale, this transaction exposes the bank to market risk on the asset as an item of inventory while it is in the bank’s ownership. This is illustrated in Exhibit 5.1, which is taken from the IFSB’s capital adequacy standard.

EXHIBIT 5.1 Credit and Market Risk Weights for Murabahah with No Binding Agreement to Purchase from the Customer

| Applicable Stage of the Contract | Credit Risk Weights (RW) | Market Risk Capital Charge |

| 1 | Asset available for sale (asset on bank’s balance sheet) | 15% capital charge (= 187.5% RW) |

| 2 | Asset is sold, title is transferred to customer, and the selling price (account receivable) is due from the customer | Based on customer’s rating or 100% RW for unrated customer |

| 3 | Maturity of contract term or upon full settlement of the purchase price, whichever is earlier | Not applicable |

Salam Financing

The salam contract is used particularly in providing financing to producers of commodities in the form of crops or livestock. The bank pre-purchases and pays for a specified quantity and quality of the commodity, for a specified delivery date, at which time the bank will sell the commodity hoping to do so at a higher price. The bank is thus exposed to market risk on the commodity from the time of pre-purchase until disposal.

Islamic Lease-to-Buy Contracts

Islamic banks use the ijarah muntahia bittamleek (IMB), a form of lease-to-buy contract, to finance the acquisition by customers of assets, both residential real estate and chattels such as vehicles. The bank first acquires the asset and then leases it to the customer, with a promise to transfer full ownership of the asset to the customer at the end of the lease. This may be done either on payment of a token amount by the customer, or by a gradual transfer of ownership pro-rata the lease payments over the life of the lease. The lease payments are thus composed of two elements: a pure rental element and a capital element whereby the customer builds up equity in the asset. The bank as lessor is exposed to market risk on the asset, in the first place between the time of acquiring the asset and the signature of the lease agreement, and thereafter on its ownership share of the asset until the customer becomes the outright owner. In addition, the bank is exposed to the credit risk of the lessee, and because of its ownership of the asset until its title is transferred to the lessee, the bank is exposed to operational risk.

Partnership Forms of Financing

The most common form of partnership contract used for financing is the diminishing musharakah, in which the bank and the customer jointly own (initially) the asset which the customer wishes to buy, with the bank usually having the major share. The customer agrees to purchase the bank’s share over time by making periodic payments, and, in the case of home purchase for example, to pay rental amounts to the bank for the right to use the share of the asset still in the bank’s ownership. The bank is exposed to market risk on this share—see Exhibit 5.1.

2.2 Capital Impairment Risk on Partnership Forms of Financing

Where financing is provided to a customer on the basis of a partnership agreement, such financing does not give the bank a debt claim that could be enforced in case the customer fails to make a scheduled payment. The bank’s claim is to its ownership share of the partnership asset. This exposes the bank to impairment of the capital it has invested in the financing arrangement that is different type from normal credit risk. The bank is also exposed to the credit risk of the customer failing to pay the lease rental. The Islamic Financial Services Board’s (ISFB’s) capital adequacy standard treats this exposure as a type of “equity position risk in the banking book,” which attracts a substantially higher risk weighting than a normal receivable.

2.3 Summary of Asset-Side Risk Specificities and Capital Implications

As indicated above, several forms of Islamic financing expose the financier to market risk, in addition to credit risk. On the other hand, the asset-based nature of such financing makes it easy for the financier to mitigate the credit risk by taking a lien on the asset in the case of murabahah, or by exercising ownership rights in the case of IMB. Also, the market risk exposure in murabahah is typically of very short duration and may be mitigated by requiring a deposit from the customer to discourage nonperformance of the agreement to purchase. Hence, with the exception of financing based on partnership forms of contract, one cannot conclude that Islamic financing is more risky for the financier, and requires more capital to back it, than conventional debt-based financing, with the proviso that the different risk mitigation techniques it calls for are competently applied.

2.4 Profit-Sharing Investment Accounts and Displaced Commercial Risk

Islamic banks typically use a form of profit sharing (and loss bearing) investment accounts (PSIA) as a Shari’ah-compliant alternative to conventional deposit accounts. These accounts are based on the mudarabah contract or, more rarely, on the wakalah contract. In either case, the bank is not liable for losses on the assets financed by these accounts except in the case of “misconduct and negligence” (i.e., breach of the fiduciary duties of integrity and due diligence). In the case of mudarabah, the bank as mudarib (fund manager) receives a contractually agreed share of any profits earned on the investment, while in wakalah the bank as wakeel receives a fixed management (agency) fee and in some cases an additional performance-related fee. Unrestricted PSIA (UPSIA) funds are invested at the bank’s discretion and are typically commingled with other funds under the bank’s control, such as those of current accounts as well as shareholders’ funds.

Holders of UPSIA usually have the right to withdraw their funds at relatively short notice, subject to forfeiting any profit share for the current period. This can expose the bank to “withdrawal risk” if the returns it pays on these accounts cease to be competitive. This may occur if the bank faces “rate-of-return risk,” an analogue of the conventional “interest rate risk in the banking book.” To mitigate withdrawal risk, an Islamic bank may be under pressure to pay returns on its UPSIA in excess of the returns that are attributable to them from those on the underlying assets. To do this, the bank may need to reduce its share of profits or fee, or even donate part of the share that is attributable to the shareholders. This pressure gives rise to displaced commercial risk (DCR), as a part of the credit and market risk of the assets financed by UPSIA is effectively displaced onto the shareholders.

As a result of DCR, an Islamic bank may need to hold capital against assets financed by UPSIA funds, even though contractually it has no exposure to such assets. In its capital adequacy standard, the IFSB designates the proportion of such assets (on a risk-weighted basis) against which capital should be held, in recognition of DCR, as alpha. Thus, in calculating the capital adequacy ratio of an Islamic bank, the denominator of the ratio will include the proportion alpha of such assets, where applicable.

2.5 Capital Structure of Islamic Banks

Islamic banks are not permitted to issue preferred shares or subordinated debt, so that their capital consists of common equity with the possible addition of innovative, and so far rarely used, types of sukuk (Islamic investment certificates) based on the musharakah contract. Some of the latter may be contingently convertible into common equity, while others may have features such that they rank after creditors and UPSIA. These latter sukuk are not subordinated in the normal sense of representing creditor claims that rank after those of other creditors (which would not be Shari’ah compliant), but the holders are in a contractual relationship with the bank, which gives them a residual claim over the assets financed by their funds that ranks after those of the bank’s creditors and UPSIA. Thus, the claims of the sukuk holders are effectively “subordinated” to those of creditors and UPSIA. Such sukuk are referred to in this chapter as “effectively ‘subordinated’ sukuk.” In the case of contingently convertible or effectively subordinated sukuk, in order to qualify as regulatory capital under Basel III (either additional Tier 1 or Tier 2), they must meet stringent criteria of loss absorbency.

UPSIA are not part of an Islamic bank’s regulatory capital. While they are loss absorbent, the loss absorbency relates only to the assets financed by their funds. Technically, according to the International Accounting Standards Board’s International Accounting Standard 32, Financial Instruments: Presentation, they are “puttable instruments” and are classified as liabilities, although their only claim (absent “misconduct or negligence” on the part of the bank) is for the net asset value, after losses, of the assets financed by their funds. However, UPSIA may be used as a form of leverage by Islamic banks, which can leverage up their income stream by raising UPSIA and taking a substantial percentage of the profits earned from investing their funds. Some degree of DCR may result from this, but apart from DCR the UPSIA are something of a “free lunch” for Islamic banks from a capital point of view.

In addition, recently some Islamic banks have started the practice of raising short-term funds in the form of deposits based on reverse commodity murabahah transactions (CMT). This enables them to take term deposits, which are repayable with a murabahah mark-up on maturity. These are obviously not part of regulatory capital, and indeed are a source of risk for the bank since the risks of the assets financed with such deposits (both credit and market risk, and also liquidity risk) have to be borne entirely by the bank. Unlike that of UPSIA, which are typically used as savings accounts, and like conventional deposits, CMT-based deposits have an effective liquidity in practice that is lower than their contractual liquidity. The effective liquidity of CMT-based deposits is the same as their contractual liquidity, which entails refinancing risk if the credit needs to be rolled over. This can contribute to liquidity crises such as that which affected the Islamic investment bank Arcapita in 2012.

2.6 Capital Adequacy

The IFSB has set out a standard, based on adaptations of the Basel Accords, for Islamic banks, including:

- Eligible capital.

- Risk weightings for Islamic financing assets, taking into account market as well as credit risk.

- The treatment of assets financed by PSIA and of DCR in the calculation of the capital adequacy ratio.

- The treatment of operational risk.

The IFSB proposes that Islamic banks, which typically lack the credit risk data necessary to implement the internal ratings–based (IRB) risk weightings on assets, should use the standardised approach with standard risk weightings.

Like the Basel Committee, the IFSB has no authority to impose this standard, this being the role of national regulatory and supervisory authorities. In line with Basel III, Islamic banks will be required to hold Core Tier 1 (i.e., common equity) equal to 4.5 percent of risk weighted assets (RWA), and Total Tier 1 (including additional Tier 1 instruments such as musharakah sukuk that meet the criteria for “going concern capital”) equal to 6 percent of RWA. The minimum total capital requirement remains at 8 percent of RWA, and the additional 2 percent may be met by Tier 2 instruments such as convertible or effectively subordinated sukuk having a sufficiently high degree of risk absorbency and other characteristics so as to meet the criteria for “gone concern capital” “Going concern capital” consists of instruments that absorb losses while the bank is still solvent, while “gone concern capital” is composed of instruments that absorb losses only upon the bank’s insolvency.

In addition to this minimum capital requirement, the IFSB follows Basel III in specifying a “capital conservation buffer” of 2.5 percent of RWA, consisting of common equity capital. The total capital requirement will thus be 10.5 percent, including 6 percent of common equity. If an institution’s regulatory capital falls below this level, but still meets the minimum of 8 percent, the supervisor will impose restrictions on capital distributions (dividends and repurchases of common equity shares) until the capital conservation buffer is restored to the required level. Finally, the Basel Committee has specified an extension of the “capital conservation buffer” in the form of a “counter-cyclical buffer” of up to a further 2.5 percent of RWA, again consisting of common equity capital. The purpose of this counter-cyclical buffer is to mitigate the macroprudential problem of cyclicality in the banking system, which manifests itself in buoyant asset values and capital levels in periods of economic expansion, and shrunken asset values and capital levels in periods of contraction, thus aggravating the economic cycle. The IFSB has proposed that the implementation of this counter-cyclical buffer be at the discretion of national supervisory authorities

2.7 Summary

For Islamic banks, capital structure and risk are linked, from a regulatory perspective, via risk weightings and capital requirements set out by the IFSB based on the Basel III Accords and the standardised approach to risk weighting. The minimum capital level obtained by applying this approach is not necessarily a measure of the economic capital that the bank should hold to provide an adequate buffer against unexpected losses. Indeed, the aim of the IRB approach was to bring regulatory capital closer to economic capital. However, the capital conservation buffer provides a mechanism that enables the supervisory authority to oblige a bank to increase its capital if the level is too close to the minimum.

3. RISK AND CAPITAL STRUCTURE IN TAKAFUL (ISLAMIC INSURANCE) UNDERTAKINGS

The capital structure of takaful undertakings is complicated by their hybrid structure and business model. The Shari’ah requires insurance to be undertaken on a mutual basis, so that the risk funds are owned by the policyholders, as are the investment funds in life or “family” takaful. On the other hand, many countries do not recognise mutual or cooperative forms of company, so that the mutual structure needs to be contained within that of a company limited by shares. Moreover, in most if not all jurisdictions, insurance solvency regulations impose capital requirements that a new mutual or cooperative insurance undertaking would be unable to meet. (Archer, Karim, and Nienhaus 2009). Mature mutual insurers were able to build up the necessary reserves over decades prior to the introduction of such regulation, but takaful undertakings have not had the time to do this.

3.1 Capital Structure, Risk, and Ancillary Capital

For the reasons given above, the typical structure of a takaful undertaking is that of a limited company with share capital and reserves, together with one or more funds that belong to the policyholders but are attached to the company by contracts (wakalah or mudarabah) under which the company as takaful operator (TO) manages the underwriting, investment, and associated activities on behalf of the policyholders. The TO thus performs the functions carried out by the management of a mutual insurer, but its board of directors is accountable to its shareholders and not to the policyholders. The policyholders’ funds are included in the balance sheet of the takaful undertaking, much as the investment account holders’ funds appear in the balance sheet of an Islamic bank.

The regulatory capital of a takaful undertaking thus needs to meet the solvency requirements of the insurance operations, and the TO also needs capital to cover its own business risks, especially the risk of its management fees being insufficient to cover its operating expenses and the “underwriting management risk” potentially arising from failure in its fiduciary duties in managing the underwriting of the policyholders’ risk fund (PRF). The solvency requirements of the insurance operations concern the underwriting risk of the risk fund or funds (provisioning risk, or the risk of underestimating the amounts needed as technical provisions) and the asset risk of the assets held in these funds. However, as noted above, in general the takaful risk funds (PRF) do not contain sufficient reserves (policyholders’ equity) to meet the solvency requirements.

The TO is not permitted by the Shari’ah to take on the underwriting and asset risks of these funds, but may provide a form of capital backing in the form of an interest free loan (qard) facility which is available to be drawn down into a risk fund in case the latter is unable to meet its obligations (i.e., is in deficiency), and which would be repayable out of future underwriting surpluses. Subject to certain conditions, such a loan facility may qualify for recognition as “ancillary capital” (as defined in Solvency II) and thus enable the takaful undertaking to meet regulatory solvency requirements. (See the IFSB Standard on Solvency Requirements for Takaful (Islamic Insurance) Undertaking—IFSB 2010). Hence, the TO needs to hold capital and an amount of sufficiently liquid assets to back the qard facility.

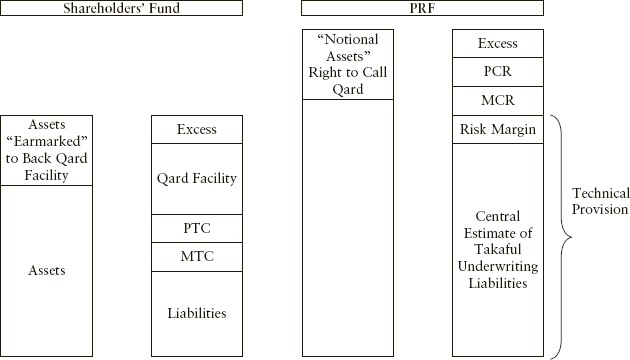

Exhibit 5.2 illustrates this point. The abbreviations are defined here: PRF (policyholders’ risk fund), PTC (prescribed target capital [of the TO]), MTC (minimum target capital), PCR (prescribed capital requirement [of the PRF]), and MCR (minimum capital requirement [of the PRF]). Thanks to the “Notional Assets” pertaining to qard, the PRF meets the PCR and there is even a bit of excess. Strictly speaking, as the qard is a loan, the right to call it (the qard facility) does not increase the net assets of the PRF from an accounting perspective, but provided it meets the criteria for ancillary capital, it is treated as doing so from a regulatory perspective.

EXHIBIT 5.2 General Approach to the Solvency and Capital Requirements for a Takaful Undertaking, where the PRF Relies on a Qard Facility to Meet Solvency Requirements

Source: IFSB Standard.

Where a qard facility is required to enable a PRF to meet its solvency requirement, it should generally be set up at a value that will provide some buffer over and above the minimum solvency requirement. This is to allow the PRF to meet its requirements on a continuous basis notwithstanding reasonably foreseeable fluctuations in asset and liability valuations. The assets backing a qard facility should be “earmarked” for this purpose. That is, they should be specifically identified and held in a discrete account separately from other assets in the shareholders’ fund. In assessing the adequacy of a qard facility for solvency purposes, the supervisory authority should look through to the earmarked assets as regards adequacy of amount and degree of liquidity.

3.2 Reinsurance via Re-Takaful

A takaful undertaking may reduce its need for capital (as well as for technical provisions) by ceding business, especially of a “high impact low frequency” nature, to a Shari’ah-compliant reinsurer or re-takaful undertaking. This will, however, expose the takaful undertaking to credit risk in respect of receivables that may become due from the re-takaful undertaking.

3.3 Summary

The total capital of a takaful undertaking consists of (a) the policyholders’ equity in the PRF and (b) the TO’s capital and reserves. The latter are divided into the amount available to meet the TO’s own need for risk capital, and the amount available to provide ancillary capital to the PRF in the form of a qard facility. For the takaful undertaking to satisfy regulatory solvency requirements, this latter amount, in conjunction with the policyholders’ equity, must enable the PRF to meet its prescribed capital requirement.

Since TOs are not permitted to issue preferred shares or subordinated debt, a TO’s capital consists of common equity. In principle, a TO could also issue forms of sukuk that provide adequate loss absorbency, but so far this does not appear to have happened.

4. CONCLUDING REMARKS

It will be apparent from the sections in this chapter that the capital structures of both Islamic banks and Islamic insurance undertakings present complexities not found in the case of conventional financial institutions. In the case of Islamic banks, a major complexity is introduced by the presence of unrestricted PSIA (UPSIA), which are profit sharing and loss bearing but not part of the bank’s own capital, and which are liable to be a source of displaced commercial risk for the bank. For Islamic insurance undertakings, their hybrid business model, with mutual risk funds contractually attached to a limited company, the TO, coupled with the lack of the equity in the risk funds required to meet regulatory solvency requirements, results in a complex capital structure wherein the TO (which is not permitted by the Shari’ah to take on underwriting risk) provides a qard facility to the risk fund. If certain conditions are met, the qard facility can act as auxiliary capital for regulatory purposes.

So far as risks are concerned, Islamic financing assets typically involve market risk as well as credit risk exposures. This clearly affects Islamic banks, but insofar as Islamic insurance undertakings hold such assets, the same applies to them.

REFERENCES

Archer, S., R.A.A. Karim, and V. Nienhaus, eds. 2009. Takaful Islamic Insurance: Concepts and Regulatory Issues. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons [Asia] Pte.Ltd.

International Accounting Standards Board. 2011. International Accounting Standard 32, Financial Instruments: Presentation, latest revision. London: International Accounting Standards Board.

Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB). 2010. Standard on Solvency Requirements for Takāful (Islamic Insurance) Undertakings. Kuala Lumpur: Islamic Financial Services Board.

Smith, J. 2009. “Solvency and Capital Adequacy in Takaful.” In Takaful Islamic Insurance: Concepts and Regulatory Issues, edited by S. Archer, R.A.A. Karim, and V. Nienhaus. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons [Asia] Pte. Ltd.