Chapter 15

Measuring Operational Risk

1. INTRODUCTION

Operational risk remained a fuzzy concept for a long time in the banking industry because it was hard to make a clear-cut distinction between operational risk and the “normal” uncertainties faced by the banks in their daily operations. Although everyone agreed that there was a risk other than the popularly known credit, market, and liquidity risks faced by a bank, the catastrophic nature of operational risk came into limelight in the wake of the huge losses incurred by Barings Bank and Daiwa Bank in the mid-1990s. The classical story of misclassification of operational risk continued for quite some time in the industry, with some of the operational risks getting misclassified as other risks. For example, no distinction was made in the losses caused by the deterioration in credit quality of the borrower and losses emanating from the fact that the credit officer did not correctly apply the credit policy. It was not uncommon to see both these losses getting lumped together under credit risk while it is quite clear that the losses in the latter case should be attributed to operational risk.

The Basel Committee for Banking Supervision (BCBS) defined operational risk as “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events. This definition includes legal risk,1 but it excludes strategic and reputational risk.”2 As per the Basel II Accord, banks are required to hold capital against operational risk, in addition to the credit and market risks, under Pillar 1. This development opened up a whole new paradigm in which banks started focusing on the measurement of operational risk using quantitative techniques.3 The Accord allows banks to choose from a buffet of options4 ranging from simple (basic indicator approach, BIA) to intermediate (standardised approach) to advance approaches (advanced measurement approaches, AMA).5 The ultimate objective is to ensure that a bank that is exposed to high operational risks maintains more capital for operational risk.

The overall expectation of the Basel Committee with regard to managing operational risks is summarised in the following extract.

Irrespective of the risk management and risk measurement practices adopted, a bank’s operational risk strategy should reflect the nature and source of the bank’s operational risks for all Operational Risk Measurement System (ORMS) elements, including regular review of predictive elements against experience. The operational risk strategy should be current and reflect material changes to the internal and external environment. Risk reporting should provide a clear understanding of the key operational risks, the related drivers and the effectiveness of the internal controls. The internal reporting framework should include regular reporting of relevant information at all levels of the bank, be transparent, responsive to changes, appropriate and support the proactive management of operational risk.6

Operational risk measurement is an important component of the operational risk strategy and framework. A sound operational risk measurement approach brings transparency into the operational risk management process. There are a host of approaches; some are less quantitative while the others are more quantitative, for the measurement of operational risk. This chapter covers the subject of operational risk measurement both from a practitioner’s perspective and Basel requirements. The rest of this chapter is divided into four sections: operational risk in the context of Islamic banks; operational risk capital calculation under Basel II; operational risk under the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) standard; and implementation issues. Some details relating to Basel II requirements are contained in the appendices.

2. OPERATIONAL RISK IN THE CONTEXT OF ISLAMIC BANKS

On the question of whether Islamic banks are subject to different types of operational risks, the answer is “yes” and “no.” There are some operational risks common to both Islamic and conventional banks. For example, the risks of failed internal processes, fraud, improper business or market practices, theft, hacking, and so forth are the common risks faced by both Islamic and conventional banks. In addition, there are some risks which are unique to Islamic banks, such as:

Does this mean that Islamic banks will have different methodologies for measuring operational risk? The answer is “no.” Merely having some unique operational risks does not necessitate new risk measurement methodologies. For example, risks arising from non-compliance with the internal policy and non-compliance with the Shari’ah requirements can be measured using the same methodology, although the likelihood and severity of losses in these cases could be very different. The difference may also be there in terms of the availability of loss history, because the bank may not have enough data for the losses caused by the non-compliance with Shari’ah requirements or it may not have classified the losses in the right category.

3. OPERATIONAL RISK CAPITAL UNDER BASEL II

The Basel II Accord prescribes three methods for calculating operational risk capital charges in a continuum of increasing sophistication and risk sensitivity. These three approaches are:

Banks can start with the simple approach, like BIA or TSA, and are expected to migrate to the more advanced approaches over a period of time once they have sufficient infrastructure in place with regard to the data and measurement methodologies. The key idea is that a bank should hold operational risk capital in proportion to the amount of operational risk involved in its activities. BIA and TSA are purely based on gross income as the basis for calculating operational risk capital, while AMA allows banks to develop their own models to calculate the amount of operational risk capital. However, in case of AMA, banks will have to prove the applicability and appropriateness of their models to the regulator. Therefore, banks will be allowed to migrate to the advanced approaches subject to regulatory approval. In addition, banks are required to follow the Principles for the Sound Management of Operational Risk issued by Basel Committee in June 2011.7

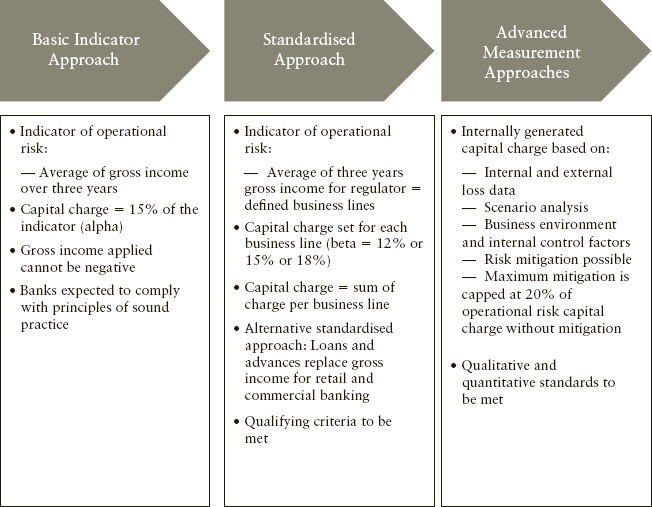

Exhibit 15.1 shows the brief summary of different methods prescribed under Basel II Accord for operational risk capital.

EXHIBIT 15.1 Approaches under Basel II for Operational Risk Capital Calculation

3.1 Basic Indicator Approach

Under the BIA, banks must hold capital equal to the average over the previous three years of a fixed percentage (denoted alpha) of positive annual gross income for operational risk. Figures for any year in which annual gross income is negative or zero should be excluded from both the numerator and denominator when calculating the average. The capital calculation, under BIA, can be expressed as follows:

![]()

Where:

KBIA = the capital charge under BIA

GI = annual gross income, where positive, over the previous three years

n = number of the previous three years for which gross income is positive

α = 15% (as determined by the local regulator)

3.2 The Standardised Approach (Including Alternative Standardised Approach)

TSA is very similar to BIA, except that bank’s activities are divided into eight different business lines. Under TSA, capital is calculated as the average over the previous three years of a fixed percentage (denoted beta) of positive annual gross income for each of the business lines. Each business line is assigned a single multiplier (beta, or capital factor β), which serves as a proxy for the industry-wide relationship between the operational losses experienced and the gross income of a particular business line. Beta ranges from 12 percent to 18 percent (as shown in Exhibit 15.2) that indicates relative risk characteristics of the underlying business line.

EXHIBIT 15.2 Beta Factors for Different Business Lines

| Business Lines | Beta Factors |

| Corporate finance | 18% |

| Trading and sales | 18% |

| Retail banking | 12% |

| Commercial banking | 15% |

| Payment and settlement | 18% |

| Agency services | 15% |

| Asset management | 12% |

| Retail brokerage | 12% |

The capital charge is expressed as follows:

![]()

Where:

KTSA = the capital charge under TSA

GI1–8 = annual gross income in a given year, as defined above in the BIA, for each of the eight business lines

β1–8 = a fixed percentage, relating to the level of the gross income for each of the eight business lines.

Banks will need to compute the capital requirement for each of the business lines for the past three years as the product of the corresponding beta factor and gross income. The total capital requirement is calculated as the three-year average of the simple summation of the regulatory capital charges across each of the business lines in each of the three years. In any given year, negative capital charges (resulting from negative gross income) in any business line may offset positive capital charges in other business lines without limit. Input to the numerator is taken as zero for the year in which aggregate capital charge across all business lines is negative.

In case an activity cannot be clearly mapped into the eight business lines, it can be mapped to the business line that most closely approximates such an activity. However, this mapping should remain consistent over a period of time and cannot be changed without the explicit approval of the regulator.

ASA is simply an adaptation of TSA wherein the exposure amount is used as the basis for the calculation of operational risk capital for two business lines, namely retail banking and commercial banking, as opposed to gross income. For these business lines, loans and advances—multiplied by a fixed factor m—replace gross income as the exposure indicator. The betas for retail and commercial banking remain same as in TSA. The ASA operational risk capital charge for retail banking (with the same basic formula for commercial banking) can be expressed as:

KRB = βRB × m × LARB

Where:

KRB is the capital charge for the retail banking business line.

βRB is the beta for the retail banking business line.

LARB is total outstanding retail loans and advances (non-risk-weighted and gross of provisions), averaged over the past three years.

m is 0.035.

3.3 Advanced Measurement Approaches

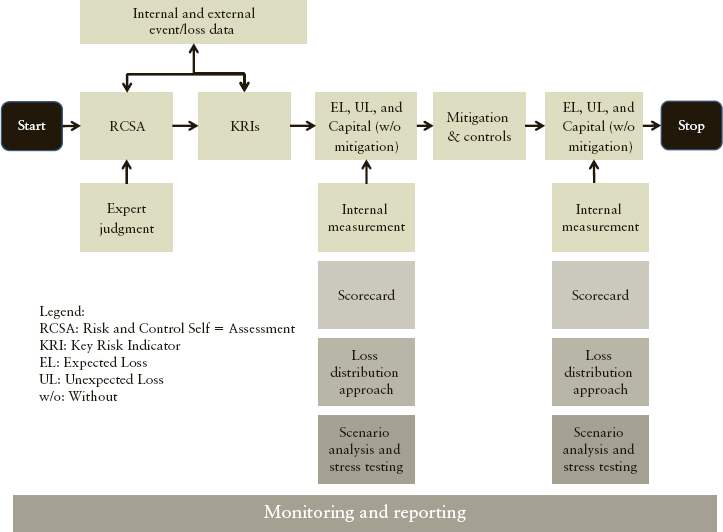

Under AMA the banks are allowed to develop their own empirical model to compute required capital for operational risk. Banks can use this approach only subject to approval from their local regulators. An AMA framework must include the use of four data elements, namely internal loss data, external data, scenario analysis, and business environment and internal control factors. This is supplemented by the data and information generated out of risk and control self-assessment and key risk indicators. The schematic of capital calculation under AMA is shown as Exhibit 15.3. AMA requires that the bank’s business lines be mapped onto the eight business lines as explained under TSA, and seven event types specified by Basel,8 and expected and unexpected losses are calculated for each of those subcategories, as applicable.

EXHIBIT 15.3 Schematic Showing the Capital Calculation under AMA

While AMA does not specify the use of any particular modeling technique, one common approach taken in the banking industry is the loss distribution approach (LDA). With LDA, a bank first segments operational losses into homogeneous segments, such as an event type for a business line. For each such unit (event type for a business line), the bank then constructs a loss distribution that represents its expectation of total losses that can materialise over a one-year horizon. Given that data availability is a major challenge for the industry, an annual loss distribution cannot be built directly using annual loss figures. Instead, a bank will typically develop a frequency distribution that describes the number of loss events in a given year and a severity distribution that describes the loss amount of a single loss event. The convolution9 of these two distributions then gives rise to the (annual) loss distribution.

In addition, banks are required to follow a set of eight qualitative requirements for the approval of AMA. These are aimed at ensuring that there are a proper governance structure and controls around the process of internal model development and implementation:

Banks having a robust control environment and managing their operational risks properly are expected to save significant capital by migrating to AMA. Once a bank has been approved to adopt AMA, it cannot revert to a simpler approach without supervisory approval.

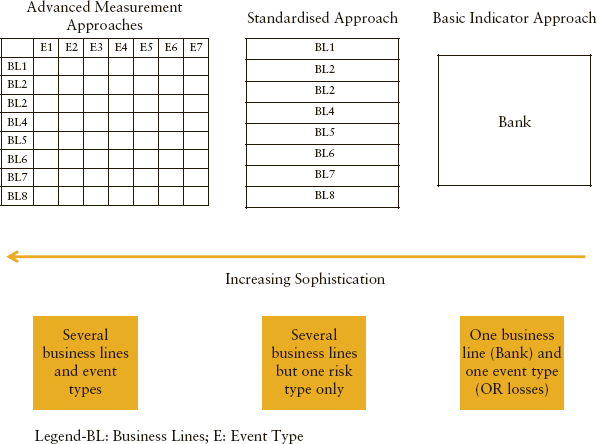

3.4 An Intuitive View of Different Approaches under Basel II Accord

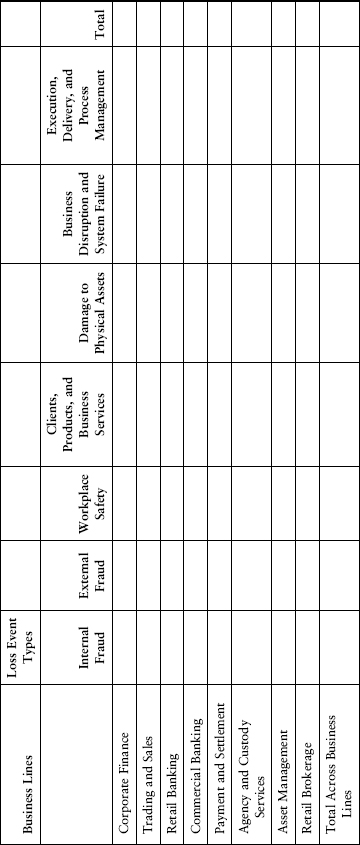

Having examined the different approaches prescribed under Basel II, it is important to analyse the underlying logic that links each of these approaches. The most sophisticated approach under Basel II is AMA as described previously. It requires the banks to compute expected losses and unexpected losses for each event type and business line. There are seven event types and eight business lines that result in a matrix of 56 cells, as shown in Exhibit 15.4. This means that banks are required to have a loss database10 for 56 different combinations of business lines and event types, although more sophisticated banks may add more categories to this matrix. Similarly, some of the cells may not be relevant for some banks, in which case they will not be computing expected losses and unexpected losses for them. Once these cells are populated, banks will then simply calculate the grand total of all the cells, taking into account the correlation among different cells for unexpected losses, which represents the amount of operational risk capital required for a bank.11 A simple summation would correspond to the assumption that the correlation is “1,” that is, “all bad things will happen at the same time.”

EXHIBIT 15.4 Business Lines and Event Types for AMA

Moving towards less sophisticated approaches, like TSA or BIA, means that the granularity of data requirements will be reduced and proxies are used for operational loss distributions. For example, moving from AMA to TSA shows that operational risk capital is required for eight business lines only and no separate assessment is required for event types (i.e., all events are collapsed into a single event). That is why the capital is calculated for eight cells only under TSA. In addition, given the anticipated data constraints faced by banks, the Basel Committee has provided gross income and beta factors as the basis to calculate operational risk capital instead of expected and unexpected losses, as applicable to AMA. Therefore, moving from AMA to TSA results in less granularity (in terms of the operational risk capital calculation) as well as the use of proxies like gross income and beta factors instead of loss distributions.

Similarly, moving backwards from TSA to BIA results in a further reduction in granularity (i.e., only one number is calculated for operational risk capital for the entire bank and the proxy remains the same, i.e., gross income).

To summarise, the hierarchy of approaches prescribed under Basel II Accord are simply based on the two main elements as depicted in Exhibit 15.5:

EXHIBIT 15.5 An intuitive view of different approaches under Basel II

4. OPERATIONAL RISK CAPITAL UNDER THE IFSB STANDARD

As per the Capital Adequacy Standards issued by the IFSB in December 2005, Islamic banks are required to follow the BIA or TSA (subject to the approval of the local regulator). The alpha factor is 15 percent for BIA (same as Basel II Accord). However, the gross income is calculated as12:

The gross income includes income attributable to restricted and unrestricted profit-sharing investment accounts’ funds, but excludes extraordinary or exceptional income. Net income from investment activities includes the bank’s share of profit from musharakah and mudarabah financing activities.

Islamic banks are required to follow the BIA. For Islamic banks looking forward to adopting TSA, the determination of beta factors is left to the discretion of the respective local regulator and expected to be in line with the Basel II Accord, as the business lines in an Islamic bank may not simply be mapped to the categories identified under the Basel II Accord.

5. INDUSTRY PRACTICE AND IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES FOR OPERATIONAL RISK MEASUREMENT

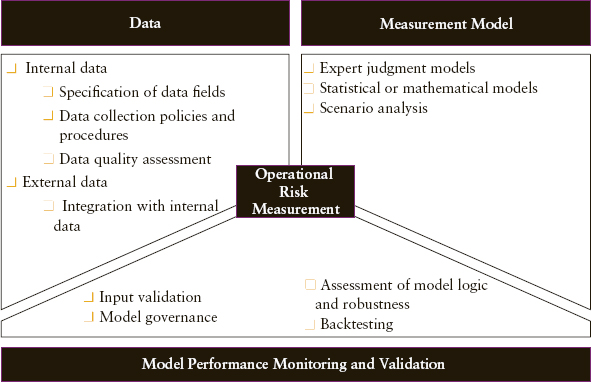

A robust approach to measuring operational risk requires the following building blocks—data, measurement model, and a mechanism to ensure that model performance is adequately monitored and validated including stress testing (as shown in Exhibit 15.6). These building blocks are common to the operational risk measurement approaches of conventional and Islamic banks. Banks face a host of issues in terms of implementing a sound operational risk measurement methodology. This subsection contains the examination of these issues and description of corresponding remedial actions.

EXHIBIT 15.6 Building Blocks of a Robust Operational Risk Measurement Framework

5.1 Data

Data are a most important element in any risk measurement exercise, be it credit risk, market risk, liquidity risk, or operational risk. The popular adage, “Garbage in, garbage out,” summarises it all. If a bank does not meet the minimum standards with regard to the quality of operational risk data, it will not be able to obtain useful output. Unlike market risk or credit risk, collection of operational risk data is more complex because for the following three reasons:

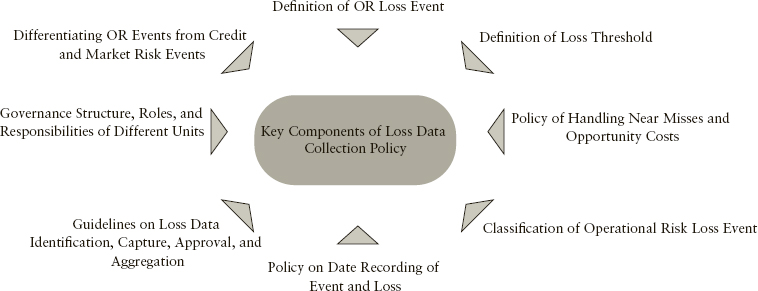

From a data perspective, the following are the five key prerequisites for a robust operational risk measurement framework:

EXHIBIT 15.7 Key Components of Loss Data Collection Policy

5.2 Measurement Model

There are several measurement models, including proprietary tools available in the market. Banks have a choice in terms of selecting a model from any of the following three categories:

5.3 Model Performance Monitoring and Validation

Operational risk measurement models are relatively new in the industry, and banks should use a comprehensive mechanism to monitor and control model risks. Some of the key areas that should be regularly and independently monitored by a bank include:

In summary, operational risk measurement is an important area for banks and other financial institutions. The magnitude of losses seen in the industry, including the recent losses in some major banks, leaves no doubt that this risk, if not measured and managed well, may have potentially disastrous consequences. Banks should not simply avoid quantifying operational risk on the grounds of unavailability of data. The first step can be the use of external data or data generated from experts’ inputs. The second step is to lay down a system so that a data capturing exercise is initiated. Thirdly, a regular assessment of operational risk should be made by the middle and senior management of the bank, and results should be reported to the board or a board-level committee. Last but not the least, internal audit, risk management, internal control, and compliance functions should regularly share information and identify potential “hot spots” so that adequate management attention can be given for the same.

APPENDIX

Under the standardised approach, banks’ activities are divided into eight business lines: corporate finance, trading and sales, retail banking, commercial banking, payment and settlement, agency services, asset management, and retail brokerage. A bank must develop specific policies and have documented criteria for mapping gross income for current business lines and activities into the standardised framework. The criteria must be reviewed and adjusted for new or changing business activities as appropriate. The principles for business line mapping as defined under Basel II guidelines are shown in Exhibit A.1.

EXHIBIT A.1 Mapping of Business Lines19

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Activity Groups |

| Corporate finance | Corporate finance | Mergers and acquisitions, underwriting, privatisations, securitisation, research, debt (government, high yield), equity, syndications, IPO, secondary private placements |

| Municipal/Government | ||

| Finance | ||

| Merchant banking Advisory services |

||

| Trading and sales | Sales | Fixed income, equity, foreign exchanges, commodities, credit, funding, own position securities, lending and repos, brokerage, debt, prime brokerage |

| Market making Proprietary positions Treasury |

||

| Retail banking | Retail banking | Retail lending and deposits, banking services, trusts and estates |

| Private banking | Private lending and deposits, banking services, trusts and estates, investment advice | |

| Card services | Merchant/commercial/corporate cards, private labels and retail | |

| Commercial | ||

| Banking | Commercial | |

| Banking | Project finance, real estate, export finance, trade finance, factoring, leasing, lending, guarantees, bills of exchange | |

| Payment and Settlement20 | External clients | Payments and collections, funds transfer, clearing |

| Settlement Agency services | Custody | Escrow, depository receipts, securities lending (customers), corporate actions |

| Corporate agency | Issuer and paying agents | |

| Corporate trust | ||

| Asset management | Discretionary fund | |

| Management | Pooled, segregated, retail, institutional, closed, open, private equity | |

| Nondiscretionary | ||

| Fund management | Pooled, segregated, retail, institutional, closed, open | |

| Retail brokerage | Retail brokerage | Execution and full service |

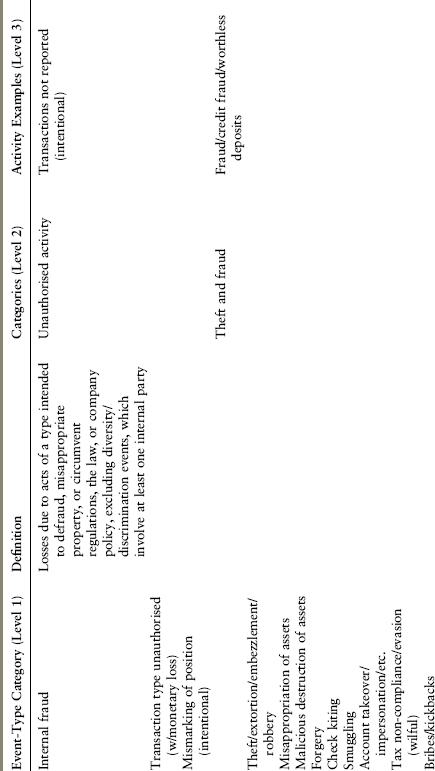

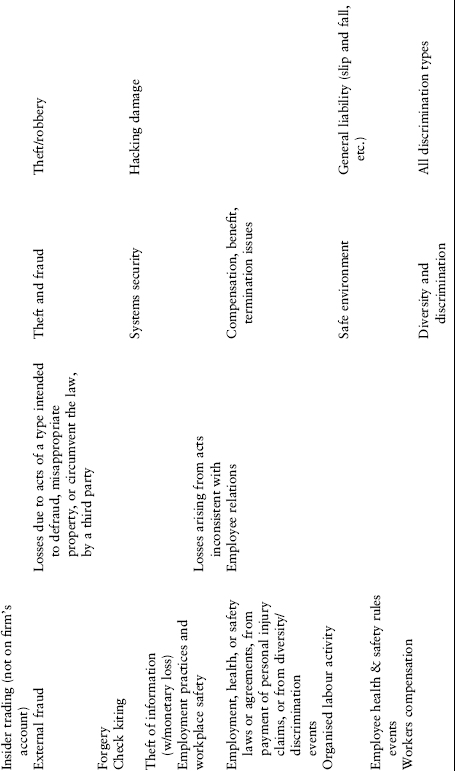

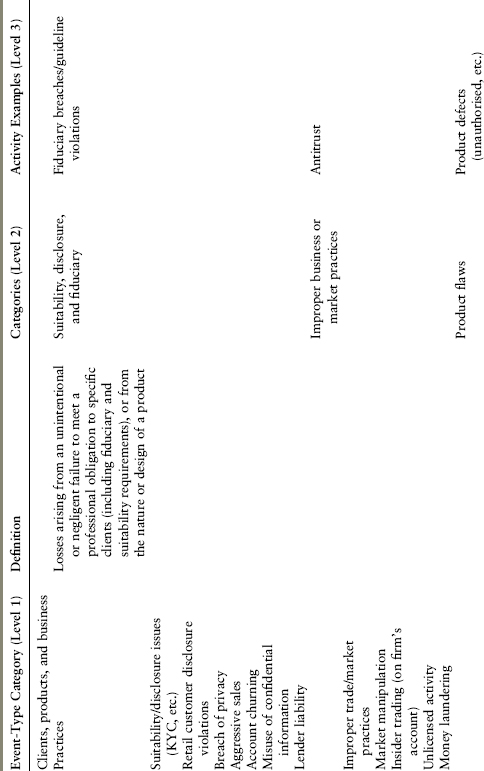

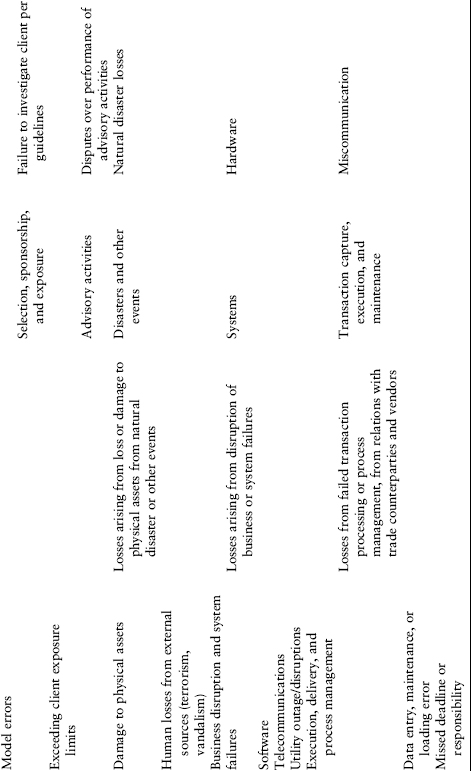

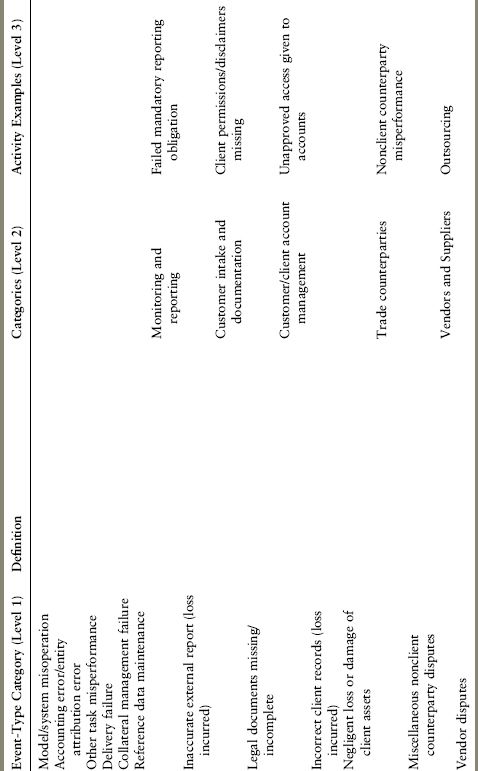

For the purposes of internal operational risk management, banks must identify all material operational risk losses consistent with the scope of the definition of operational risk. The loss event types defined under Basel II are presented as Exhibit A.2.

EXHIBIT A.2 Detailed Loss Event Type Classification21

NOTES

1. Legal risk includes, but is not limited to, exposure to fines, penalties, or punitive damages resulting from supervisory actions, as well as private settlements.

2. BCBS, “International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards—A Revised Framework” (also referred to as Basel II Accord), updated November 2005, 140.

3. Qualitative assessment of operational risk has been practiced in the banking industry for quite some time in different forms. For example, the internal audit departments have been assessing the risks and controls, including operational controls, in different banks mainly on a post-fact basis.

4. Subject to the local regulatory requirements.

5. The specific details of the capital calculation for operational risk are covered in Section 3.2.

6. BCBS, “Operational Risk—Supervisory Guidelines for the Advanced Measurement Approaches,” June 2011, 2.

7. Prior to this, banks were required to follow BCBS’s Sound Practices for the Management and Supervision of Operational Risk, 2003.

8. Details are given in Exhibit 15.4 and appendices.

9. A convolution is a mathematical operation on two functions producing a third function that is a modified version of one of the original functions. It is somewhat similar to cross-correlation.

10. Specific data issues faced by banks during the implementation of AMA or an advanced approach are discussed in Section 5.1.

11. Under AMA, it is expected that a bank’s regulatory capital for operational risk will be the sum of its expected losses and unexpected losses due to operational risk, unless the bank can show that it has accurately measured and made provisions for the expected losses. For credit and market risk, expected losses are routinely covered by provisions, but this may not be the case for operational risk, in which case capital needs to be provided.

12. IFSB, Capital Adequacy Standards for Institutions (other than Insurance Institutions) offering only Islamic Financial Services, December 2005, 18.

13. Exhibit A.1, Appendix.

14. Exhibit A.2, Appendix.

15. For example, not more than 10 percent of the missing data fields, reconciliation errors not exceeding 5 percent, and so on.

16. Include sense checking of data and its relevance to the business of the bank, technical rules like parsing, data duplication, missing value treatment, min-max rules, and so on.

17. Please refer to Section 3.3 for more details.

18. Some practitioners may classify this methodology under Expert Judgment, although it is usually a combination of quantitative analysis and expert judgment.

19. BCBS, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards—A Revised Framework (also referred to as Basel II Accord), updated November 2005, 254.

20. Payment and settlement losses related to a bank’s own activities would be incorporated in the loss experience of the affected business line.

21. BCBS, International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards—A Revised Framework (also referred to as Basel II Accord), updated November 2005, 257.