Chapter 17

Securitisation in Islamic Finance

Securitisation as a financing option has long been a popular mechanism for raising funds in the conventional context. In Islamic finance, the concept of securitisation takes on a more fundamental role as an intermediation between the issuer and the investor, the nature of the underlying assets, and the financial market at large, leveraging off the “asset-based” nature of the Islamic industry as a whole. Islamic securities known by the Arabic term sukuk (investment certificates) are issued for this purpose. This chapter will seek to provide an analysis on securitisation from a sukuk angle, studying its growth, depth, and potential through recent issuances, historical benchmarks, and performance using empirical data from a practitioner’s perspective.

1. PREFACE: AN OVERVIEW OF THE SUKUK MARKET

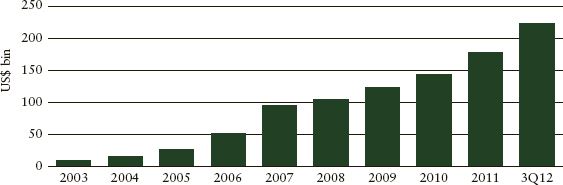

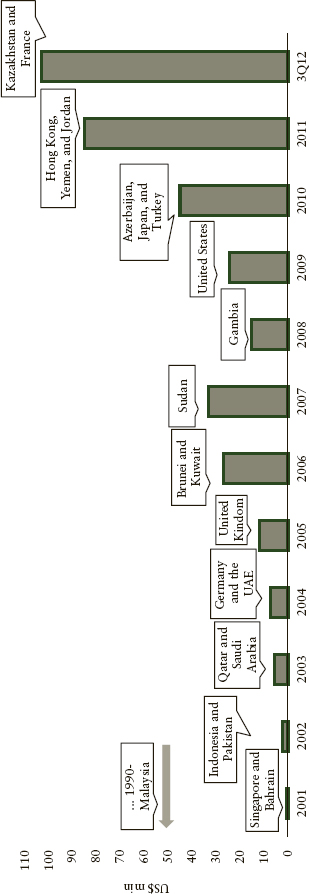

The sukuk market provides a range of much needed Shari’ah-compliant instruments having return characteristics, making them substitutes for conventional fixed-income instruments for investment by financial institutions and other investors that seek Shari’ah-compliant instruments as an alternative asset class. The “fixed-income-like” characteristics of such sukuk derive not from contractual obligations of the originator or issuer, as with conventional fixed-income instruments, but from the nature of the underlying securitised assets, which have a highly predictable income stream. As such, these sukuk are classed by financial analysts as “fixed income.” Between 2001 and 2011 the primary sukuk market grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 59.2 percent to reach US$85.1 billion at the end of 2011, as shown in Exhibit 17.1. Sukuk issuance has made a remarkable expansion in 2011, outpacing 2010 estimates, seeing a year-to-date increase of 88.4 percent at the end of 2011. Similarly, the secondary sukuk market reached US$178.2 billion worth of outstanding papers at the end of 2011, as shown in Exhibit 17.1. Issuers include Islamic financial institutions, corporates and sovereigns in both the Asian and Middle Eastern regions. The rapid growth of the Shari’ah-compliant “fixed income” market comes at a time of serious turmoil in the conventional bond markets against the backdrop of a global financial crisis, and underscores the strength and economic fundamentals of the sukuk market.

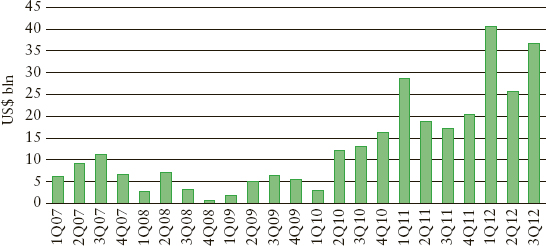

EXHIBIT 17.2 Sukuk Issuance on a Quarterly Basis

Source: KFHR.

Note: The average quarterly issuance in 2012 is US$34.3 billion as compared to only US$20.0 billion in 2011 and US$11.2 billion in 2010.

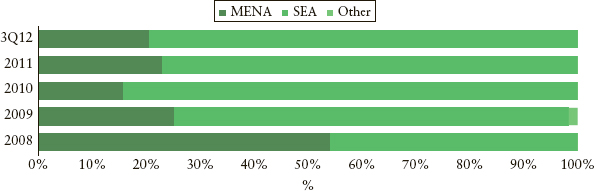

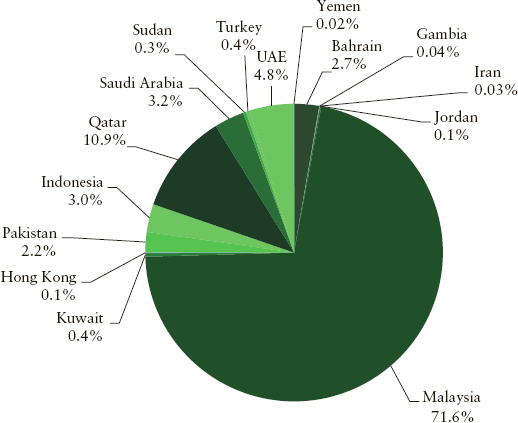

By region, Southeast Asia (SEA) holds the largest share of sukuk issuances, representing 76.9 percent of the primary market in 2011, followed by the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (23.0 percent), as shown in Exhibit 17.3. The year 2011 saw a number of new jurisdictions open up to the sukuk market, among them potentially large Muslim markets including Jordan, Iran, and Yemen, as shown in Exhibit 17.4. The depth of the market is further underscored by the multitude of investors who have raised sukuks (Exhibit 17.5). Notably, a key development was the introduction of the international financial district of Hong Kong, which has been planning to debut the market since 2007 but was delayed due to the global financial crisis. This initiative, when recognised, will at once open a new market to investors with links to China and new asset classes which will catapult sukuk into a new realm of investment.

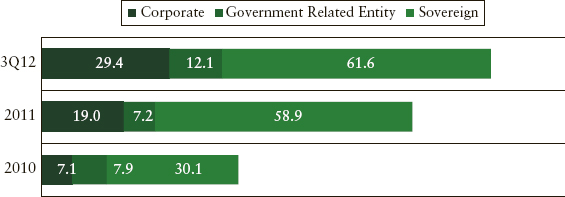

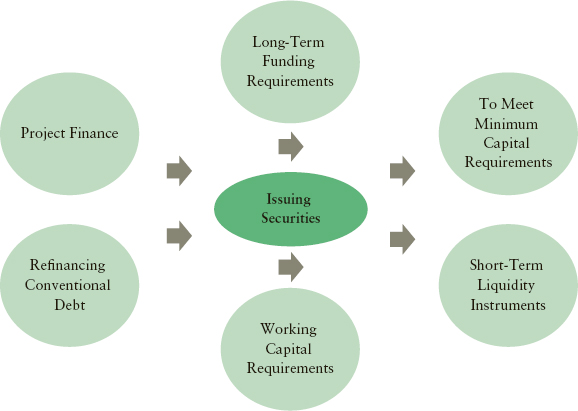

Based on 2011 data, sukuk issuances were dominated by sovereign issuers looking to raise funds as a means of replenishing fiscal budgets for socioeconomic activity. In 2011, corporates had also returned to the primary market after either cancelling or delaying plans in 2010 as the Dubai real estate bubble burst and the impact of the financial crisis was felt throughout Asia and the Middle East. On a year-on-year basis, corporate sukuk are up 167.6 percent to US$19.0 billion issued in 2011 from the US$7.1 billion issued in 2010 as shown in Exhibit 17.5. Of these corporate sukuk, US$12.4 billion or 65.0 percent were issued in Malaysia, while US$3.1 billion (16.4 percent) and US$2.0 billion (10.8 percent) were issued in the UAE and Saudi Arabia, respectively. Of the total issuances in 2011, corporate issuers made up 21.9 percent of the U.S. dollar amount versus 16.3 percent in 2010. There are a number of reasons for corporates to issue sukuk. These include financing the following:

- Project, infrastructure and real estate financings.

- Corporate financings.

- Investment funds of all types.

- True asset securitisations.

2. SECURITISATION AND SUKUK: SOME GENERAL REMARKS

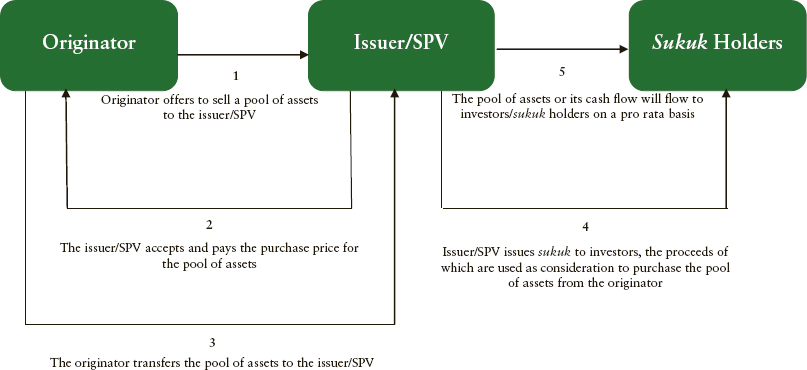

Financial institutions and businesses use securitisation to fund their operations and to immediately realise the value of a cash-producing asset. The pool of assets is usually composed of assets such as financing, but can also be trade receivables or leases. In most cases, the originator or provider of assets is expecting a regular stream of payments over those assets. By pooling the assets together, the payment streams can be used to support principal payments on securities.

One of the benefits for the originator from securitising assets is that the originator receives full value for assets rather than an extended payment stream spread out over time. Thus the originator will invest this sum of proceeds received from the securitised assets to fund further growth in its asset book. This supplements the need for the originator to raise funds by more traditional methods. Also, securitisation structure permits firms to effectively move and hold their assets off-balance sheet. This generates higher leverage and greater economies of scale. Furthermore there are many other purposes for originators in choosing the Islamic securitisation path, as shown in Exhibit 17.6.

A company that wants to obtain financing through securitisation begins by identifying assets that can be used to raise funds. These assets typically represent rights to payments at future dates and are usually referred to as “receivables.” The credit risk that these payments may not be made on time is an important factor in valuing the receivables. As long as the originator can reasonably predict the aggregate rate of default, it can securitise even those receivables that present some risk of uncollectibility. A statistically large pool of receivables due from many obligors, for which payment is reasonably predictable, is generally preferable to a pool of a smaller number of receivables due from a few obligors.

After identifying the assets to be used in the securitisation, the originator transfers the receivables to a newly formed special-purpose corporation, trust, or other legally separate entity often referred to as a special-purpose vehicle (SPV). The transfer is intended to separate the receivables from the risks associated with the originator. Further, it will be important to the originator (especially for regulatory capital purpose) that the assets are no longer treated as being on its balance sheet. For this reason, the originator will often structure the transfer so that it constitutes a “true sale,” a sale that is sufficient under bankruptcy law to remove the assets from the originator’s bankruptcy estate.

The SPV issues securities in the Islamic capital markets to raise funds in order to purchase those assets. The SPV, however, must be structured as “bankruptcy remote” to ensure that the purchasers of these securities see their investment as being against the securitised assets only and not subject to the risk of failure of the SPV. Otherwise, the ratings of the issuer of the capital market securities will be adversely affected. Bankruptcy remote in this context means that the SPV is unlikely to be adversely affected by a bankruptcy of the originator.

In securitisation, the originator partly “deconstructs” itself by separating certain types of excellent quality assets from the risks generally associated with the originator. It can then use those assets to raise funds in the capital markets at a lower cost than it, with its associated risks, could have raised the funds directly by issuing more debt or equity. The originator retains the savings generated by these lower costs, while investors in the securitised assets benefit by holding investments with lower risk.

The major difference between Islamic securities and the traditional conventional ones is the element of Shari’ah compliance. Although they share a similar process, structure, and end result, there are a few key principles that must be adhered to in order for these securities to pass the Shari’ah-compliance test. These include, for example, the prohibition of interest, the inability to engage in excessive speculation or risk taking, limitations on the use of the sale of financial assets and their use as collateral, and the exclusion of certain industries, like those involving alcohol, gambling, or pork. In particular, while the underlying assets in conventional securitisations are predominantly financial assets, because of Shari’ah prohibitions on trading in debt, the underlying assets in sukuk securitisations are predominantly non-financial (see Exhibit 17.7).

EXHIBIT 17.7 Sukuk versus Conventional Bond

Source: HSBC Amanah, KFHR.

| Parameter | Sukuk | Conventional Bond |

| Issuer | A sukuk issuer shall be engaged in Shari’ah-compliant business activities. | An issuer of conventional bonds is not limited in its business activities. |

| Investor base | Enjoys a wider investor base from both Islamic and conventional investors. | Conventional bonds can only tap conventional investors. |

| Ownership | Investors take direct or beneficial ownership of an underlying asset or pool of assets. | A conventional bond is purely the financial debt of the issuer. |

| Administrative cost | Additional fees in terms of legal and Shari’ah advisory fee. | No additional administrative costs associated with conventional bond issues. |

| Financing cost | A larger pool of sukuk investors creates more demand, hence may help to achieve slightly more competitive pricing. | A comparatively smaller pool of conventional bond investors suggests that there is less demand for the instrument. |

One of the major areas of concern for Islamic financial institutions relates to the acceptability of the securitisation business (i.e., the content of the “pool of assets” rather than the actual process of pooling those assets). Islamic financial institutions tend to ensure that each and every asset in the pool is Shari’ah complaint. Since the concern is for the nature of each asset on its own and not for the pool as a whole, most commonly securitised Western assets may not be acceptable for a Shari’ah-compliant securitisation. The assets in Western securitised pools are invariably interest-bearing debt instruments, such as credit card receivables, mortgages, car loans, and so forth, which are unacceptable to investors seeking Shari’ah-compliant investment. It is therefore important for Islamic financial institutions to concentrate on originating their own Shari’ah-compliant assets, which may include leasing, equity (partnership) contracts and murabahah contracts. In most jurisdictions, however, murabahah contracts are non-tradable because of the Shari’ah prohibition on trading in debt.

The basic principles that must be adhered to when originating and structuring Islamic securities include:

- Funds raised through securitisation must be utilised for only Shari’ah-compliant purposes.

- All credit enhancement features must be structured in a permissible form.

- Most jurisdictions require that the majority of the pooled assets must be nonfinancial assets in order for the securities to be freely traded on the secondary market. Permitted percentages of financial assets range from 30 to 49 percent, depending on the jurisdiction.

- Assets should not be associated with unethical or exploitative operations or with speculation and uncertainty (gharar) from nonproductive investments.

- A sufficient element of ownership must be conveyed to investors.

Having stated the above, the Islamic securitisation market has had its fair share of controversy in recent years. In early 2008, the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) issued a pronouncement whereby they stated that the majority of Islamic securities (or sukuk) did not actually conform to the requirements of the Shari’ah. Their points of criticism were focussed around securities that were structured under the musharakah and mudharabah contracts (profit- and loss-sharing ventures) which included a purchase undertaking over the invested asset portfolio to repurchase it at the issue price, thereby violating the Shari’ah requirement that return should be associated with exposure to risk (in effect, such an undertaking may be considered to turn the structure into a type of debt contract).

Nevertheless, the market has yet to fully incorporate the comments into the various sukuk transactions due to the lack of better, more viable alternative structures.

In brief, Islamic securitisation is more prudent and less aggressive than conventional securitisation because of the risk sharing principles laid down under Islamic financing principles. Shari’ah-compliant securitisation is likely to increase the availability of capital and reduce financing costs for originators and restock the funding sources for institutions; it will provide investors the option of tailor-made products that meet their portfolio requirements, including diversification and risk reduction.

The combination of securitisation techniques with credit derivatives and risk transfer devices allows various market participants to develop innovative methods of transforming risk and to tap into sectors that were otherwise not open to them.

3. MARKET FOR SECURITISATION IN ISLAMIC FINANCE

The use of sukuk and asset securitisations to access the financing side of Western capital markets, and as a backbone element in the development of Islamic capital markets, is still one of the fastest growing areas in Islamic finance. Islamic securitisation is so far growing and expected to grow on an increased basis in many countries, in particular the Gulf Cooperative Council (GCC) and Asian countries, as can be seen in Exhibit 17.8.

The number of active locations involved in Islamic securitisation is increasing significantly every year, and at the end of 2011 this reached 22 different destinations, including both Muslim and non-Muslim countries. The main challenge for potential issuers unfamiliar with Islamic principles is to find and allocate appropriate assets that comply with Shari’ah for the securitisation. For the likes of Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) and other financial service sector players, it is fairly straightforward to gather assets that could be securitised due to their entire operations and portfolios being in compliance with Shari’ah. The most securitised assets are residential mortgages, as well as auto financing and consumer finance. However, it is expected that the types of assets that will be securitised will become more diversified in the future when the growing market becomes used to the mechanisms and structures.

In recent years, Islamic securities have been structured utilising major infrastructure projects as underlying assets, giving investors beneficial ownership and entitling them to the underlying revenues or cash flows from the project. This has proven to be a successful model of connecting the financial services sector to the real economy without the downside risks of conventional financial assets. A number of benefits can be drawn from this observation:

- Funds are channelled to productive and beneficial projects in the real economy.

- Increased ratings compared to issuer standalone rating due to bankruptcy remoteness.

- Strength of underlying asset base.

- Similar risk/return profile to conventional papers.

- Increased investor base to both conventional and Islamic investors.

- Lower costs.

- Better liquidity (currently confined to emerging Islamic countries with a thriving sukuk market).

As such, sukuk or Islamic securitisation has proven to be a viable solution for infrastructure and project financing in developing markets, which could be further promoted in developed markets such as the United States, where infrastructure spending is becoming an increasing necessity. Such financing instruments may also attract flush Middle Eastern and Asian investors, as well as sovereign wealth funds looking to invest according to Islamic principles.

4. SECURITISATION STRUCTURES

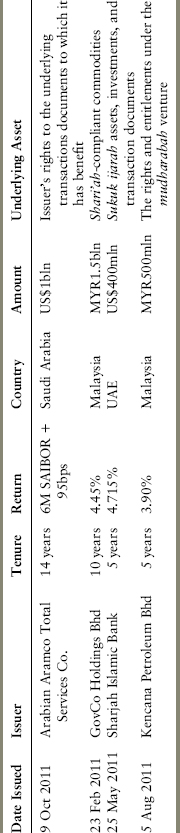

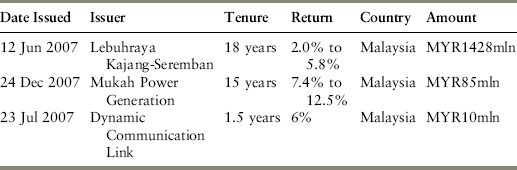

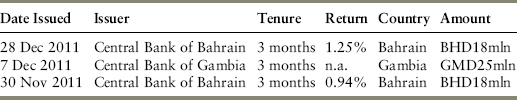

The various structures used in Islamic securitisation are either asset backed or asset based. To date, apart from a number of sovereign sukuk issuances by the Central Bank of Bahrain, only a handful of successful asset-backed Islamic securities have been issued around the world, as shown in Exhibit 17.9.

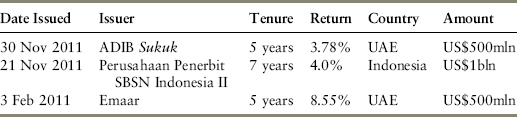

EXHIBIT 17.9 Selected Sukuk Issuance

Source: KFHR.

There are two types of classifications under asset-backed sukuk (these refer to the issuer-SPV, not to the underlying assets):

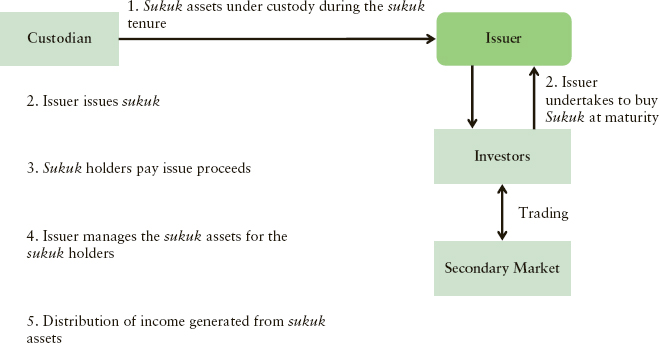

Each structure typically shares features that are shown in Exhibit 17.10.

EXHIBIT 17.10 Islamic Asset-Backed Securities

However, Islamic securitisation utilises the asset-based approach for the vast majority of transactions, and this has become an increasingly popular and more flexible means to securitise assets. Structures based on Islamic concepts such as ijarah, musharakah, mudharabah, and istisna’a have been introduced and are gaining popularity. Most of the sukuk issuances to date have been ijarah sukuk as well as murabahah sukuk, largely based on the nature of the assets underlying the structures. The ijarah sukuk securitisation model also has similar cash flow structures to the conventional securitisation structures, which makes investor education far more effortless and swifter to market.

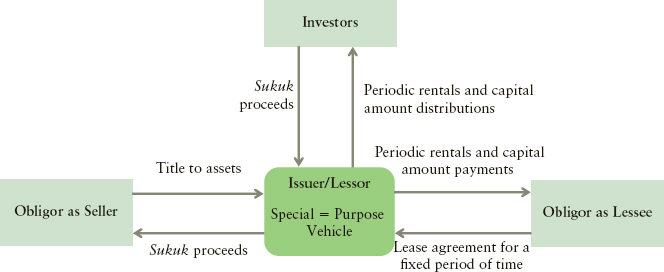

4.1 Ijarah Sukuk

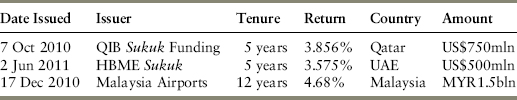

Ijarah sukuk is commonly used for project financing. It is a leasing structure coupled with a right available to the lessee to purchase the asset at the end of the lease period (similar to a finance lease). The rental rates of return on the sukuk can be either fixed or floating, depending on the agreement. Exhibits 17.11 and 17.12 give some examples of successful ijarah sukuk issuances.

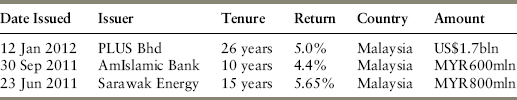

EXHIBIT 17.12 Selected Sukuk Ijarah Issuances

Source: KFHR.

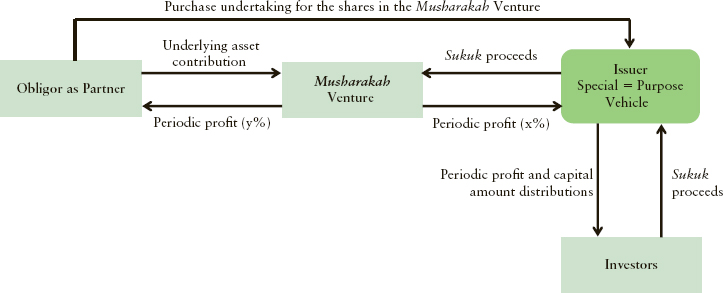

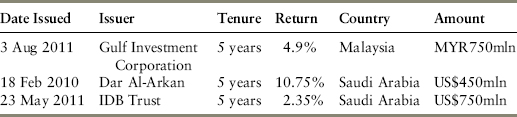

4.2 Musharakah Sukuk

Under the musharakah partnership structure, pricing could be linked to performance of the underlying assets, rather than benchmark rates, on a profit-and-loss-sharing basis as shown in Exhibit 17.13. Investors could receive profits in excess of their actual investment contribution based on a pre-agreed ratio, but any loss will be shared on the basis of the equity participation. Exhibit 17.14 gives some examples of successful musharakah sukuk issuances.

EXHIBIT 17.14 Selected Sukuk Musharakah Issuances

Source: KFHR.

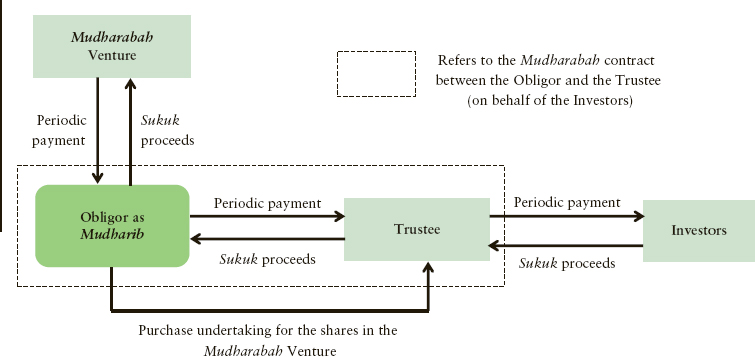

4.3 Mudharabah Sukuk

Mudharabah-based sukuk is another partnership structure with profit sharing, but in this instance, there is no sharing of losses, as shown in Exhibit 17.15. The return to the investors from mudharabah sukuk would be higher than that under the musharakah structure, as the risk is higher. The return profile would also be smoother, as the profit-sharing payouts would be adjusted in highly profitable years to maintain payouts in less profitable or loss-making years. Exhibit 17.16 gives some examples of successful mudharabah sukuk issuances.

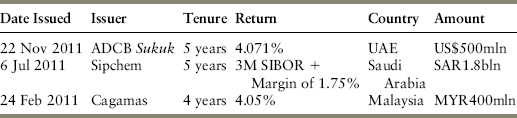

EXHIBIT 17.16 Selected Sukuk Mudharabah Issuances

Source: KFHR.

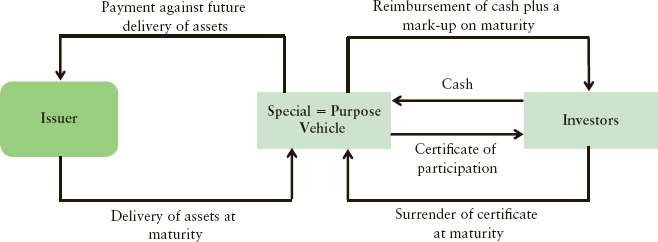

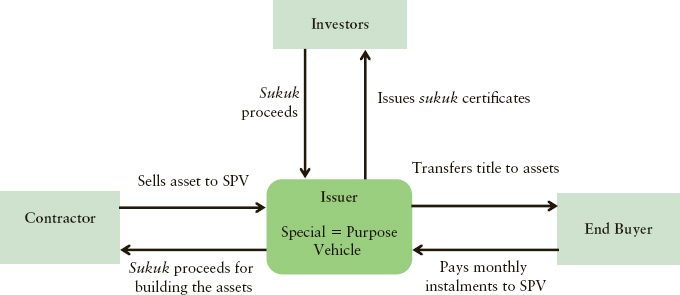

4.4 Istisna’a Sukuk

This type of sukuk is used for financing of green-field infrastructure projects, given that for such projects the underlying assets do not yet exist. Under the principle of istisna’a, the issuer will sell to the financier the identified assets which have yet to be constructed. The financier will then immediately sell back the assets to the issuer based on deferred payment terms, as shown in Exhibit 17.17. Exhibit 17.18 gives some examples of successful istisna’a sukuk issuances.

EXHIBIT 17.17 Structure of a Generic Istisna’a Sukuk

Source: KFHR.

Note: Completed property / project is leased or sold to the end buyer. The end buyer pays monthly instalments to the SPV. The returns are distributed among the sukuk holders.

EXHIBIT 17.18 Selected Sukuk Istisna’a Issuances

Source: KFHR.

4.5 Al-Istithmar Sukuk

This type of structure is used for direct investments in a bundle of assets, which make it hybrid in nature. The underlying assets will combine both financial assets such as murabahah receivables with tangible assets such as ijarah lease rentals in a ratio of 70:30 respectively. They are asset-based sukuk and are usually traded in the secondary market. A diagram of a generic al-istithmar sukuk can be seen in Exhibit 17.19. Exhibit 17.20 gives some examples of successful istithmar sukuk issuances.

EXHIBIT 17.19 Structure of a Generic Al-Istithmar Sukuk

Source: KFHR.

Note: Some jurisdictions impose certain limits on a portfolio for the certificates to be tradable whereby the proportion of the nonfinancial assets has to be more than the receivables. Some Shari’ah scholars require the majority portion to be at least 51 percent, and others insist that it should be at least two-thirds of the portfolio.

EXHIBIT 17.20 Selected Sukuk Istithmar Issuances

Source: KFHR.

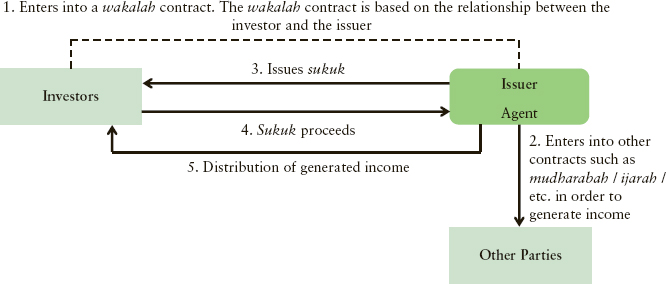

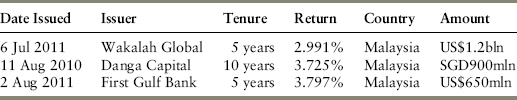

4.6 Wakalah Sukuk

AAOIFI defined these as certificates that represent a project or a particular activity carried out according to the wakalah principle, where a wakil or a representative is appointed to manage the project on behalf of the sukuk holder. As wakil, the issuer is entitled to receive a management fee. To generate income, the issuer enters into other contracts, such as mudharabah and ijarah, with other parties. Proceeds from the sukuk issuance will be used by the issuer for investments in particular project based on Shari’ah principles, as shown in Exhibit 17.21. Exhibit 17.22 gives some examples of successful wakalah sukuk issuances.

EXHIBIT 17.22 Selected Sukuk Wakalah Issuances

Source: KFHR.

4.7 Salam Sukuk

Salam refers to a sale in which the buyer makes payment in advance, and the delivery of the asset is deferred by the seller, as shown in Exhibit 17.23. Salam structures are more popular for short-term financing. Exhibit 17.24 gives some examples of successful Salam sukuk issuances.

EXHIBIT 17.24 Selected Salam Sukuk Issuances

Source: KFHR.

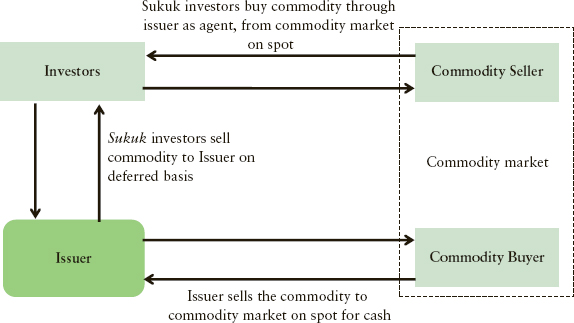

4.8 Murabahah Sukuk

In this case the issuer of the certificate is the seller of the murabahah commodity, the subscribers are the buyers of that commodity, and the realised funds are the purchasing cost of the commodity, as shown in Exhibit 17.25. The sukuk holders own the murabahah commodity and are entitled to its final sale price upon the resale of the commodity. Exhibit 17.26 gives some examples of successful murabahah sukuk issuances.

EXHIBIT 17.26 Selected Murabahah Sukuk Issuances

Source: KFHR.

5. REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

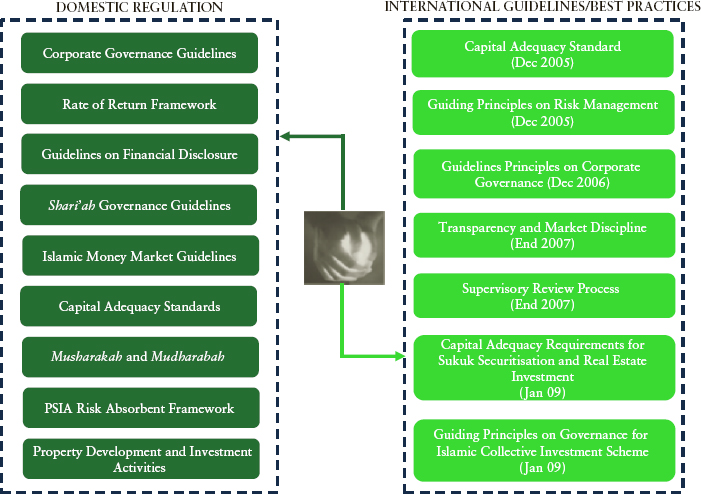

In many regions of the world, Islamic securities are either self-regulated (under the auspices of the Shari’ah) or fall under conventional regulation designed to regulate conventional bonds and other short-term securities. In certain Western developed markets, regulators have amended sections of capital market regulatory framework in order to ensure that Islamic securities would not be disadvantaged in any regards in comparison to conventional instruments. This could be in the form of removing tax hurdles or clarifying the listing process to ensure Shari’ah compliance.

Meanwhile in developing Islamic markets, more sophisticated regulation has been developed aimed at incorporating the specific nature of the distinct Shari’ah-compliant structures of Islamic securities. Two prime examples are Malaysia and Bahrain, where independent regulation has been developed for the proper oversight of Islamic securities.

Malaysia has been the pioneer in developing regulation for Islamic securitisation, setting an example for other countries wishing to establish or incorporate an Islamic securities market. In 2004, the Securities Commission of Malaysia issued a guideline on the offering of Islamic securities in the country, which outlined the following key aspects:

- The submission of proposals.

- Offering Islamic securities under a self-regulated scheme.

- Documents/information required.

- Eligible persons.

- Appointment of Shari’ah advisors.

- Regulatory approvals.

- Rating requirements.

- Underwriting

- Mode of issuance.

- Utilisation of proceeds.

- Additional requirements for Islamic securities programmes.

- Disclosure requirements to investors involving profit/profit and loss sharing elements.

- Time frame for approvals.

Together with other legislation, Malaysia is seen as a well-regulated and transparent market for Islamic securities, as shown in Exhibit 17.27. In fact, the Securities Industry Development Corporation (SIDC), the training and development arm of the Securities Commission Malaysia, has been one of the major training centres for regulators from around the world on implementing a sophisticated and transparent Islamic financial industry.

Bahrain, among a few other countries, requires adherence to the Accounting and Auditing Organisation for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) standards, which are enforced by the Central Bank of Bahrain, Bahrain’s regulatory body for the financial services industry. AAOIFI issued its first standard on Islamic securities in 2002, one year after the first sukuk issuance in the country. AAOIFI was established in 1990 by a number of Islamic financial institutions together with the Islamic Development Bank, which spearheaded its establishment. AAOIFI has issued numerous Shari’ah standards aimed at clarifying the methods of issuing and investing in Islamic securities.

Other Arab and Muslim countries stand out for their industry-driven approach to Islamic finance as opposed to high dependence on a regulator-led model, as is the case in Malaysia and Bahrain. While the former approach has promoted real progress in attracting global players, there are concerns regarding a lack of core regulatory infrastructure development. For instance, some Arab and Muslim countries do not have a specific Islamic finance policy for regulators or laws mandating Shari’ah compliance or regulation specifically promulgated for the Islamic finance industry, nor have they adopted banking regulations specifically developed for Islamic banks. As such, Islamic banks are regulated and supervised in the same way as traditional banks on conventional prudential regulatory frameworks. Exceptions include the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain, both of which have pursued Islamic finance as a niche segment in their economic diversification strategy and are now home to the largest concentration of Islamic finance assets. Both have strived to become regional financial centres, keeping their markets open to foreign banks.

In the GCC countries in general, regulatory and supervisory authorities have adopted the approach that the role of government and supervisory authorities is not to shape evolution and development of Islamic finance by imposing their will and dictating their views, but rather to conduct extensive consultations with the industry and facilitate evolution and development by creating a healthy competitive environment for all participants. However, the approach adopted by Saudi Arabia is somewhat different. While respecting that Islamic finance has some specific and unique features, Islamic banks are viewed as generally exposed to the same types of risks as a conventional bank. Thus, as in other Arab and Muslim countries, the same regulatory approach has been adopted towards Islamic and conventional banks.

The Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), which was set up in 2002, has issued a number of international prudential standards and guidelines for Islamic financial institutions. In common with other international standard-setters, the IFSB has no enforcement powers, which are the prerogative of national regulators and supervisors.

The most important challenges in the areas of regulation, supervision, and international harmonisation that are hindering the faster growth of Islamic securitisation include the following.

The multiplicity of Shari’ah boards and judgments across jurisdictions impede the homogeneity of products, and create uncertainty for clients and investors about the cross-border acceptability of Shari’ah rulings. While Islamic finance is becoming increasingly internationalised, it remains a collection of segmented, weakly coordinated local operations. Since the industry has a great potential to facilitate cross-border capital flows and financial integration, efforts are needed to resolve or at least mitigate the uncertainty regarding the acceptance of Shari’ah rulings. This entails more international cooperation on the part of home and host regulators and standard-setters.

The legal and regulatory framework of Islamic finance needs further work to make it consistent with international practices, while maintaining the unique features of Islamic finance and not compromising Shari’ah principles.

As in conventional finance, there needs to be an integrated crisis management framework in Islamic finance to ensure that any emerging crisis in the Islamic financial system will be adequately managed. Such a framework involves having the mechanism and vehicle to address short-term liquidity problems, removing troubled assets from the balance sheets of financial institutions and resolving solvency issues in Islamic financial institutions. Having an adequate crisis management framework also raises the issue of designing Shari’ah-compliant deposit insurance systems.

Consumer protection and financial literacy in Islamic finance is an emerging area for regulators.

6. SECURITISATION: A GROWTH DRIVER FOR ISLAMIC FINANCE

As at year-end 2011, sukuk issuances soared by 90.2 percent year-on-year from US$45.1 billion in 2010 to US$85 billion, underpinned by the following factors:

- The implementation of the financial masterplans and government initiatives which will act as the backbone of growth throughout the coming years.

- Increase in sovereign issuers utilising the sukuk market for monetary policy and fiscal management purposes.

- Economic growth and development in emerging markets. Despite the IMF revising world GDP growth to 4.0 percent for 2011 from 4.3 percent (2010: 4.6 percent), Asia, the Middle East, and other emerging markets are still expected to outperform with 6.4 percent growth in 2011.

Although sukuk yields have surged recently due to a downturn in investor confidence, they still remain below the trailing three year average. This had encouraged a number of corporate issuers to deliberate possible sukuk issuances in anticipation of executing the deals at the most beneficial timing.

Sukuk showed strong resilience in spite of the Middle East uprisings, leading to a more than threefold year-on-year jump in issuance in the Middle East and North Africa as issuers took advantage of cheaper costs of raising funds.

Based on the issuance momentum seen in 2011, the global sukuk issuance for 2012 is expected to show strong growth of 25–30 percent, characterised by the following:

The 2012 sukuk market will be driven by global economic activities, accommodative monetary policies, continued sovereign fundraising to support economic growth, as well as the revival of private sector projects. The IMF projects world GDP growth to remain at 4.0 percent for 2012, supported by strong growth in Asia, the Middle East, and other emerging markets. This will ensure the revival of infrastructure projects on both the conventional and Islamic capital markets.

More sovereign issuers are anticipated to tap the sukuk market in 2012 as governments will continue to raise funds to support economic growth and fund fiscal deficits.

New emerging market players as well as new non-Islamic issuers are expected to tap the sukuk market.

Increasing demand and popularity for Shari’ah-compliant products and structures post–global financial crisis will form a strong demand base for sukuk moving forward.

Initiatives taken by various jurisdictions in developing legislative and regulatory frameworks, as part of efforts to attract foreign investments, would allow these new players to explore the sukuk industry for the first time.

A number of new jurisdictions have shown interest in issuing sukuk, such as Egypt, Senegal, and Nigeria while France, Japan, and Hong Kong continue to make regulatory inroads for future issuances.

The demand for sukuk was previously limited outside Asia and the GCC until a few years ago. Potential new sukuk markets that will emerge in 2012 include Oman, Thailand, and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries. Elsewhere, non-Muslim Western financial institutions and corporates in the United States, United Kingdom, the Europen Union and Central Europe are also becoming more actively involved in this industry, and are interested in issuing sukuk to refinance existing corporate debt or to finance working capital and expansion activities, including acquisitions. As in the year 2011, we expect new issuances in 2012 to be dominated by government institutions and the construction and financial services industries.

In light of current economic conditions, investors are expected to seek new forms of funding as well as to diversify from traditional asset classes to tap the capital markets for liquidity. This is expected to create a whole new ballgame for sukuk structures and issuances, creating the impetus for innovation within the Islamic finance industry. There is currently a lack of products in the market that can translate across borders into jurisdictions with varying requirements. To achieve internationalisation of the sukuk market and boost cross-border financing, this requires more sophisticated products with a mixture of principles involved to adapt across borders. In this regard, the GCC, despite its relative structural and regulatory prudence compared to the world’s largest sukuk issuer, Malaysia, is perhaps the region creating the most impetus on the innovation front. Earlier this year, the GCC saw an issuance of a multisource deal incorporating a Shari’ah tranche, which looked at monetising receipts of the toll road system in Dubai.

In summary, prospects for the sukuk-led securitisation industry are expected to remain bright. Having grown at a CAGR of 57.0 percent over the past decade, the sukuk industry is expected to exceed the US$130.0 billion mark as at the end of 2012 (2011:US$85.1 billion), and could potentially exceed the US$169.0 billion mark by year-end 2013. Risks to the sukuk market moving forward include the fiscal woes of the European countries, which have no clear-cut solutions in sight; the persistent deficit of quality papers; and the lack of an application of Shari’ah principles to suit the growing demand of project-based financing needs in the Middle East and Asia.