CHAPTER TWO

Asian Companies Are Poised to Triumph in the Merger Endgame

One of the primary themes of Western mergers and acquisitions (M&A) is the inexorable drive toward consolidation. Indeed merger endgame theories seem to suggest a single optimum of a handful of companies dominating an industry. In Asia, there will be room for multiple “local optima” since significant fragmentation exists between markets and customers. This requires companies to make a decision about which markets and customers they wish to serve and how to drive consolidation at that level. Early analysis shows different industries will have varied outcomes.

We believe that a number of Asian industries will undergo a wave of consolidation over the next few years. We also believe that Asian companies and brands will emerge as national and as regional champions in this formative merger endgame.

Consolidation follows a predictable path as industries develop and mature. In Western markets like the United States and Europe, a handful of companies tend to dominate an industry as it reaches maturity, first nationally, then regionally within its continent, and then across the Western world, and finally, globally. In Asia, consolidation will play out differently. Asia’s markets are fragmented in many critical ways: regionally, culturally, linguistically and, most importantly, economically. The disparity makes it tough for companies such as Vodafone, a telecommunications company that has a 20 to 40 percent market share in 13 European countries, to replicate that success in Asia.

Consolidation is inevitable, but key Asian industries will merge along segmental lines. Companies that come to dominate each segment will be those that understand it best. For example, after the industry consolidates, two or three soft drink brands might not dominate a country such as India, or an entire region; instead, champions will dominate a specific price point or segment within the soft drink market. Insights into local tastes, preferences, and purchasing power will be critical.

This paves the way for Asian national players with a strong connection to local consumers and a solid plan in place to ride the incoming waves of consolidation and emerge triumphant in Asia’s merger endgame.

THE DRIVE TOWARD CONSOLIDATION

Industry consolidation is inevitable. Two key facts of business life are behind this truism. The first is economies of scale: A larger company that produces a high volume of goods has lower costs per unit. The second is this: Big fish eat smaller fish. Companies can gain market share and score other corporate wins, some of which are psychological, by acquiring smaller competitors. The inevitable quest for lower costs and the intrinsic urge to consume competitors drive consolidation. Consolidation helps improve industry economics, which is beneficial after a period of intense competition.

The level of fixed costs associated with an industry will impact the number of players operating in that particular space. The higher the fixed costs, the more concentrated an industry will be. High fixed costs are a major barrier to entry for new players. Companies that have made those core investments and generated the cash needed to sustain ongoing high-cost capital expenditure plans have a head start. For example, the automotive, steel, chemicals, and pharmaceutical industries all have high fixed costs and are concentrated, even on a global scale.

The inevitable push toward consolidation and concentration should be factored into any company’s long-term business plan. Every strategic move should be made with the merger endgame in mind. The endgame for a particular industry could be five years from now—or 15. Either way, companies need to plan for it today.

A.T. Kearney conducted long-term research a few years ago on high-value M&A. The conclusions were remarkable: Though M&A activity can seem chaotic, consolidation follows a set of laws and can be predicted. The research, which included more than 25,000 companies in 24 industries and 53 countries, found that all industries consolidate and follow a similar course.

Each industry passes through three stages: opening, scale, and dominance. During the opening phase, a few pioneers dominate a nascent industry. The level of concentration is high because only a handful of players have entered this space. As time goes on, the opening phase is marked by increasing fragmentation as more competitors pile into the industry. The market is ripe and wide open, and there’s room for many competitors to grow organically to meet untapped demand. A number of factors contribute to this stage, including deregulation and the creation of a new business or industry. Consider, for example, the myriad budget airline operators that emerged in Thailand and Indonesia after Malaysia-based AirAsia, the region’s first low-cost carrier, proved this fledgling business model could work in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, deregulation of Asia’s telecommunications industry ended the era of government monopolies and opened the floodgates to a slew of competitors. As mobile phones became more affordable and widespread, more rivals came on the scene, limited only by the number of licenses the regulators handed out.

Toward the end of the opening phase, the market becomes saturated, profit margins start to shrink, and earnings growth begins to slow. The market becomes less fragmented, and size starts to matter. As competitors grow, they begin to reduce costs by achieving economies of scale. Their larger size can prevent hostile takeovers. The smaller companies, who can’t achieve scale, become takeover targets.

The next phase is about building scale. As the industry consolidates, the concentration increases. The more aggressive companies acquire more small fish, and the less competitive are subsumed. In time, the number of players drop dramatically.

The industry enters the dominance phase. A handful of companies lead the sector and together command the majority of the market share. The dominant players strive to solidify and reinforce their hard-won position. They have reached a size that puts them out of reach of hostile takeovers. At this point, the industry hits equilibrium. Mergers and acquisitions become a rarity, and antitrust laws block further consolidation. At this stage, M&A is about the selective exchange of business units to strengthen core competencies and clean up the company’s portfolio.

As one industry completes a round of consolidation, another wave will be touched off in a different industry, which triggers another industry into restructuring mode to increase shareholder value. These waves are transcending borders, pushing the merger and consolidation endgame into the global arena.

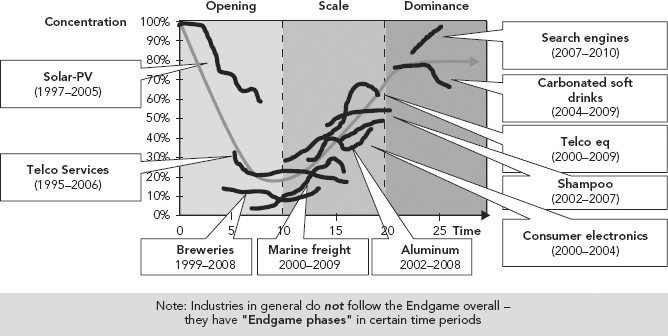

The three cycles, or phases, in this endgame scenario create a U curve when mapped out on a graph that compares industry concentration against time (see Figure 2.1).

Though the three-stage merger endgame scenario provides a compelling conceptual underpinning to what we are witnessing in the real world, we need to caution against using it as a definitive predictor of industry scenarios. Many industries can take an inordinate amount of time to reach the scale or dominance phases. Other industries, once reaching the dominance phase, will commence another industry cycle of opening, particularly if new technology or deregulation lowers the entry barriers for new entrants again.

The important takeaway for executives is this: You can determine where on the U curve your industry sits and project what stage is likely to come next. If your company is in the opening phase of an industry, grow organically and keep an eye out for potential acquisitions. As your industry heads toward the scale phase, get ready to eat or be eaten. Know where you want to sit in the pecking order at the end of the dominance phase before it arrives because, by then, it will be too late. Companies that want to be at the top of the food chain in the merger endgame need to develop a plan of attack and build momentum during their industry’s opening and scale stages. Every strategic move a company makes should be made with the endgame in mind even if that stage is 5 or 15 years away. Success isn’t about luck. It’s about planning ahead.

ASIA’S FRAGMENTED MARKETS CREATE OPPORTUNITY

European companies can typically sell a product or brand to a wide target market across the European Union (EU) using one strategy. This is not true in Asia. The Asian market is more complex and fragmented than the many states within the EU. There’s a wider array of cultures, languages, and incomes among Asia’s consumers. Asia’s developing economies are at radically different stages of development; and within each country, many tiers of consumers exist with different purchasing power levels.

To understand how fragmented Asia is as a market, consider some of the following figures. There are 23 official languages spoke in the EU; it sounds like a lot, but it’s about half that of Asia. There are 44 languages spoken in Asia’s seven major emerging economies alone, namely China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and the Philippines. This doesn’t even include regional dialects or languages from Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries such as Korea and Japan.

The income gap yawns wider in developing Asia than in the Western markets. Consider the range of per capita GDP, or purchasing power parity, across emerging Asia: At one end, we have Singapore, where per capita GDP hit $62,100 in 2010, outstripping even the United States; at the other end is India and the Philippines, where per capita GDP was just $3,500.1

By comparison, the gap is barely noticeable in the West. The United States had a per capita GDP of $47,200 in 2010; the entire EU has a per capita GDP of $32,700. Even if you look at individual European countries, the variance is low: Consider Sweden at $39,100 and Italy at $30,500. The difference is only a few thousand dollars. Asia’s variance is so wide, it strips out an entire decimal point.

What does this add up to? Severe segmentation. More than 54 percent of Indians earn less than one dollar a day, yet luxury brands ranging from Louis Vuitton, Mercedes-Benz, and Montblanc do brisk business by targeting the top niche of India’s consumers. Income is one difference. Culture, education, language, and location, be it rural or urban, impact spending decisions. And that’s just within one country. So many kinds of consumers are all over the marketing map that one bank, telecom company, or beer brand would have difficulty achieving the broad market dominance in Asia the way they do in Europe or the United States.

ASIAN PLAYERS WILL DRIVE LOCAL OPTIMA

All this adds up to a major marketing challenge and an opportunity. Though our global endgame curve indicates that all industries tend to consolidate toward an optimum number of dominant companies, Asia’s diverse and segmented markets means there’s room for multiple local optima. Instead of two or three companies dominating an entire sector, several companies will dominate a specific price point, or segment, within the industry. Asian companies are best positioned to win that race. Parsing a market by specific tastes, incomes, and cultures requires deep local knowledge.

This is already starting to happen. Our research shows Asian champions are dominating sectors and segments that are in the scale and dominance phases that we described earlier.

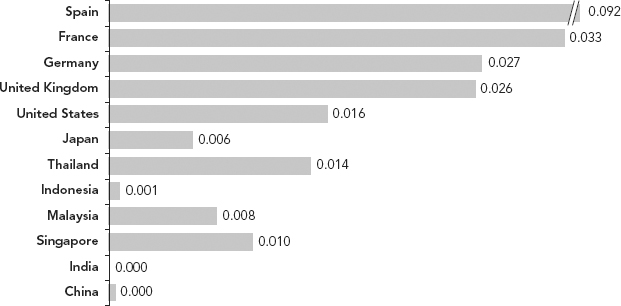

We put together a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), which measures market concentration, for several key Asian industries including banking, telecoms, retail, automotive, alcohol, soft drinks, and packaged food. A high index figure indicates the industry is concentrated, with a few key players, and a low figure indicates less concentration with many small firms.

The data highlight which industries are concentrated and which are fragmented and, therefore, ripe for future consolidation. The data show Asian companies are emerging as winners in industries that have consolidated. The success of these companies underscores our analysis and provides impetus to other Asian companies in different industries to get their M&A plans in order before their industry moves to the next endgame stage.

Let’s zero in on several key industries and examine what stage they’re in, what’s coming next, and who is in the driver’s seat.

CONSOLIDATION LOOMS FOR ASIA’S NASCENT RETAIL SECTOR

Asia’s retail sector is one of the most highly fragmented industries in the region. The retail sector in large, developing countries like India, China, and Indonesia is so fragmented that it barely registers on the HHI (see Figure 2.2). To put Asia in context, we ran the numbers on the retail sector of several developed, Western markets, including Spain, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Those countries have a high index ranking, indicating consolidation has produced a mature, concentrated retail industry dominated by a few large players.

Modern retail formats and chain stores are making inroads in urban areas of most Asian countries, but independent shops and mom-and-pop stores still dominate much of the region. Many countries have imposed ownership limits on foreign retailers: India still doesn’t grant licenses to foreign retail companies like U.S.-based Walmart. Malaysia, meanwhile, requires foreign hypermarkets to sell a 30 percent stake to an ethnic Malay partner to secure an operating license. Still, foreign investors are making inroads. France’s Carrefour and Walmart have expanded aggressively in China, and UK retailer Tesco has moved into most big Asian markets. Local players have achieved scale, regionally and at home. Hong Kong-based Dairy Farm, which owns the Wellcome, Cold Storage, and Shop ’n Save grocery chains, the Giant hypermarket chain, and the Mannings and Guardian drug store chains, has a strong presence across greater China and Southeast Asia.

If we were to put Asia’s emerging retail markets on our consolidation endgame graph, they would populate different parts of the U curve. India’s nascent industry is still in the early part of the opening phase. The real estate needed to bolster modern retail—namely shopping malls—is taking off. Protectionist laws keep foreign retailers out. The unorganized sector, meanwhile, reigns supreme. Modern grocery retailers, for example, commanded just 2 percent of India’s grocery market share in 2010, according to Euromonitor. That figure rose from 1 percent in 2005, an important signal that modern retail is growing. Still, the country has a long way to go in this opening phase before consolidation begins. This could spell opportunity for savvy players who can map out a strategy that will put them on top during these early, go-go growth days.

At the other end of the spectrum is Singapore, which is home to one of emerging Asia’s most concentrated, least fragmented retail sectors. The Singapore story offers a glimpse of what’s to come for countries like India and lends credence to our theory that Asian champions will emerge. The four biggest retailers, in terms of value, are Asian companies: NTUC FairPrice Co-operative Limited, a Singaporean grocery chain; Hong Kong’s Dairy Farm International, whose Cold Storage grocery chain and Mannings and Guardian pharmacy chain dot the city-state; Sheng Siong Supermarket, a Singaporean low-cost grocery store; and Takashimaya, a Japanese department store. Western brands and chains do figure but way down on the list.

China and the rest of Southeast Asia fall in between India and Singapore on our endgame curve. These countries are moving into a critical stage where size starts to matter, and M&A will drive consolidation.

China’s retail sector is growing fast but is consolidating and becoming an increasingly important theme. Carrefour and Walmart helped build the organized retail sector during the mid-1990s with big box hypermarket retail outlets that attracted local shoppers in droves. Local retailers followed suit and have built on their momentum. To achieve the kind of price advantages that heavyweights like Walmart and Carrefour command, leading Chinese retailers are scrambling to expand their distribution networks by opening new outlets, accepting franchising agreements for third-party operated outlets and engaging in M&A activities.2

The market is hitting the bottom of our U curve in China: The combined market share of the top 10 retailers in China rose from 4 percent in 2004 to 7 percent in 2010, according to Euromonitor. That’s a long way off the situation in the United States, where the top 10 retailers accounted for 30 percent of sales. Still, the sharp rise in the combined share of the biggest players indicates that China is heading into the scale stage of the consolidation cycle. The biggest companies are gaining competitive advantage and will snap up smaller companies who fall behind.

Consider China Resources Enterprise Limited: Its flagship Vanguard supermarket chain purchased around 2,000 stores from regional players between 2004 and 2010.3 The Hong Kong-listed company, which is majority-owned by state-owned enterprise China Resources Group, has interests in retailing, beverage, food processing and distribution, and real estate. It’s still much on the acquisition trail: In July 2011, it bought Hongkelong Department Store, which runs 21 hypermarkets in Jiangxi province, for RMB3.69 billion ($573 million).

China Resources Enterprise Limited had more than 3,300 stores in China as of March 2011—including supermarkets, drug stores, and Pacific Coffee outlets—and plans to double that figure. “We aim to have 6,592 retail outlets by 2015 and make it to the top three retailers in China; one effective way of accomplishing that task would be mergers and acquisitions,” China Resources Group chief executive officer Hong Jie told Business China in March.4 Gome Electrical Appliances Holdings Limited, one of the largest electronics and appliance specialist retailers in China, plans to have 2,000 outlets bringing in RMB180 billion ($28 billion) in sales by the end of 2014. These kinds of aggressive targets signal that retailing in China will continue to consolidate and centralize over the next few years.

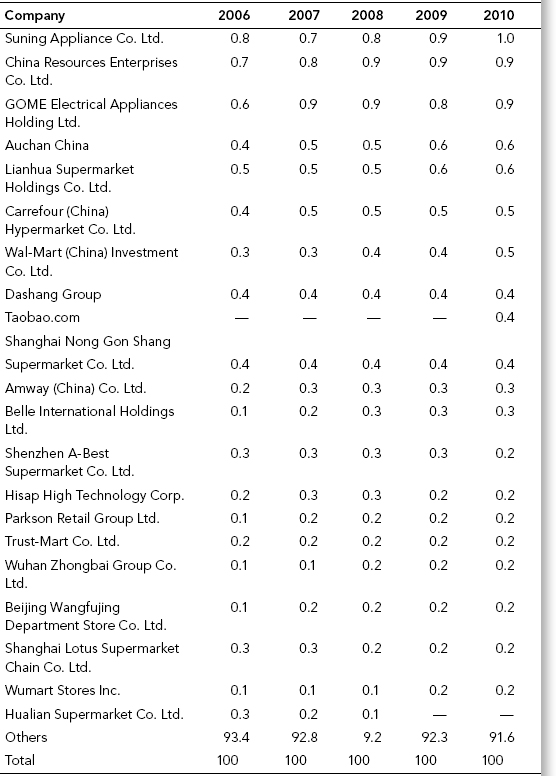

Chinese retailers have outperformed their international competitors, lending credence to our theory that local champions will emerge in Asia’s merger endgame. The top three retailers in China, by market share, are all local companies: Suning Appliance Company Limited, China Resources Enterprise Co. Ltd., and GOME Electrical Appliances Holdings Ltd. (see Table 2.1).

TABLE 2.1 Local Companies Dominate China’s Retail Scene

Retailing Company’s Shares: % Value 2006 to 2010 (% retail value excluding sales tax)

Source: Euromonitor’s January 2011 “Retail China” report.

To be sure, the foreigners are big contenders: France’s Auchan, Carrefour, and Walmart come in third, fifth, and sixth respectively. But the local players dominate. Chinese companies account for seven of the top 10 retailers.

One of the biggest stories in Southeast Asia’s retail sector in 2010 was Carrefour’s decision to pull out of the region, where it helped build the hypermarket sector, and to concentrate on markets such as China, where it held a more dominant position. In November 2010, the company sold its Thai holdings to French competitor Casino Guichard-Perrachon, which owns the Big C hypermarket brand in Thailand but immediately backtracked on the rest. Shortly after the sale of its Thai assets, Carrefour announced it had canceled plans to sell its stores in Singapore and Malaysia. A number of analysts believe the rush of bidders, combined with strong economic data, made Carrefour realize it was exiting the region at the wrong time.

Southeast Asia’s retail sector looks ripe for further consolidation, and the next few years will likely produce a smaller slate of dominant players as modern retailers draw more of the local consumers and the larger players eat the smaller players.

Retailers have expanded aggressively in Malaysia, and the sector is moving toward saturation, according to Euromonitor. Sales growth will come from higher-priced products, not from organic growth. A saturated market populated with many players gripped by slowing margins means consolidation is around the corner. Small retailers will start to lose market share, and the larger players will grow because they have the resources to plow into new stores and acquisitions.

A quick look at the top retail companies, by market share, shows that Asian champions are ahead of the game. Six of the top 10 players in Malaysia are Asian, including Malaysia-based The Store Corporation, which operates grocery, department, and hyperstore outlets; Econsave Cash & Carry, another local hypermarket company; Dairy Farm International and Hutchison Whampoa, both from Hong Kong; and AEON Group and Seven &i Holdings, which are both from Japan. Seven &i Holdings, which operates 7-Eleven stores, was bought from its U.S. founders in 2005 by Seven-Eleven Japan Company Limited. The three foreign retailers in the top 10 are Tesco PLC, Carrefour SA, and Amway.

The picture in Thailand mirrors Malaysia to a certain degree: Five of the top 10 retail companies, by market share, are Asian, including Thai-owned retailers Central Group, Home Product Center PCL, The Mall Group Co., and Fresh Mart International, which operates a local chain of convenience stores, and Japan’s Seven &i Holdings.

Foreign retailers do have a big presence in the hypermarket space. Tesco had the second-largest retail market share in Thailand in 2010, and French hypermarket owner Casino Guichard-Perrachon, which operates the ubiquitous Big C Hypermarket brand in Thailand, was number four. In 2010, Casino bought out Carrefour’s Thai hyperstores, which held the number five spot, further expanding its reach.

The retail sector in Thailand sits somewhere between the opening and scale phases on our endgame graph. There is still plenty of room for multiple players to achieve organic growth, but the larger companies are keen to acquire competitive advantage through M&A, as evidenced by the rush to snap up Carrefour’s assets. As Malaysia’s retail sector moves into consolidation mode, it could trigger a wave in neighboring Thailand as these dominant companies move to cement their position and match shareholder returns.

THE TALE OF TWO SOFT DRINK MARKETS: WHY LOCAL OPTIMA WILL EMERGE

The soft drink sector offers up informative lessons for any company striving to tap Asia’s consumer boom. Consider how China’s soft drink market is evolving: The urban market is starting to look saturated, and growth will come in the rural areas and from new products. Manufacturers have moved quickly to segment soft drinks to target different price points and different tastes to spur drink sales and fight saturation.

Global and local companies are investing heavily in product development to cater to consumer’s specific needs. China Huiyuan Juice Group Limited, for example, has recently launched a drink called Huiyuan Juizee Pop, which contains more than 10 percent real juice to meet a demand from increasingly health-conscious consumers. The company intends to invest RM5 billion to develop the sales and marketing reach of this new product, which analysts think could alter the competitive landscape of the carbonated drinks category, according to Euromonitor.

Multinational soft drink companies such as Coca-Cola and PepsiCo hold the leadership position on a national scale, but a strong demand exists from lower-tier cities and rural areas for more affordable, economy brands, according to Euromonitor. Asian companies, particularly from China and Taiwan, know that and are working to produce products to tap that demand. Although Pepsi and Coke might lead nationally, local companies dominate a number of regional markets. For example, Ting Hsin International has a leading position in the Northwest China region. The company, which is owned by a Taiwanese family but headquartered in Tianjin, China, is spending heavily to keep a lock on that position. In 2010, Ting Hsin International announced plans to invest $440 million in a new factory and operations center in Shaanxi.

In East China, Coca-Cola and Ting Hsin dominate sales, but Guangdong Jiaduobao Beverage & Food Company Limited saw the largest increase in sales, by value, in Southern China in 2010. Its best-selling Wong Lo Kat brand of canned herbal tea helped buoy its position, illustrating that consumers prefer tastes that are familiar to them. Indeed, ready-to-drink tea and Asian specialty drinks saw the fastest growth in the key South China market in 2010. These segments are dominated by Chinese and Taiwanese brands, underscoring how local insights on taste and preferences give Asian companies the advantage.

A similar scene is playing out in India. Coke and Pepsi dominate national sales, but local companies such as Parle Agro and Dabur are leading the charge in customization. Like their Chinese counterparts, they are investing heavily to develop new products with new tastes and price points to cater to different segments among the diverse Indian demographic, according to Euromonitor. Strong demand for value-for-money products has led to a proliferation of powder concentrate versions of existing drink products. Price is one issue; taste is another. Indian consumers like what they know and veer toward products that suit their palate. One of the most competitive subsegments is lemon/lime drinks that taste similar to a traditional lemon drink called nimbu pani. Local companies have understood that for a while, but the global companies aren’t standing still. Coca-Cola launched a new lemon-flavored juice drink in 2010 in a bid to squeeze into this particular niche.

Local flavor is fast becoming an important theme in India. Soft drink companies that operate in every segment—energy drinks, fruit juice, carbonates, and concentrates—introduced new products in 2010 that have favored flavors. Some companies ran ad campaigns that year that highlighted the tradition and “Indianness” of their products to establish brand equity, according to Euromonitor. Pepsi and Coke may dominate overall sales, but it’ll be tough to “out-India” the Indians as this competition heats up.

India’s consumers, like those in China, are becoming increasingly health conscious, and Euromonitor predicts the carbonated drink segment, in particular, will see a steady shift away from dominant colas toward lemon/lime drinks, non-colas, and lower calorie options. That may open up another avenue that favors local champions.

Companies have plenty of time to plan their endgame strategy. India’s soft drink industry is in the growth phase and remains broad and diverse. Parts of the country’s soft drink sector are so localized and fragmented that the national brands don’t hold much sway. Consider, for example, India’s Northeast. Low incomes and political unrest have kept national brands at bay, and numerous regional companies have sprouted instead, offering low-cost, locally made drinks. India’s per capita consumption of soft drinks was around eight liters in 2010; that figure is forecast to double as national soft drink companies begin to pay more attention to the less developed parts of India.

HENAN BROUHAHA HERALDS BEER CONSOLIDATION DRIVE

China is home to the world’s largest beer market, and everyone wants a piece of the pie. Every world-class beer company operates in China through their own facility or a joint venture. Though a few big brands dominate, the rest of the market is fragmented with many small local players. The industry is hitting saturation, and the consolidation race is well under way.

Consider the activity that took place in Henan over the past two years. Henan, China’s second most populous province, was home to about 40 small and mid-sized beer companies. National and global breweries have flocked to the province to snap up stakes in the province’s fragmented beer industry. Beijing Yanjing Brewery Group Corporation, for example, paid RM227 million ($35 million) for a 90 percent stake in Henan Yueshan Brewery, the province’s third-biggest brewer, in August 2010. The acquisition gave Beijing Yanjing, the fourth-largest beer producer in China, a beachhead in Henan to compete with market leaders China Resources Enterprise Ltd., Tsingtao, and Anheuser-Busch InBev in the key mid-China region, according to Euromonitor.

The floodgates opened the following year. Anheuser-Busch InBev paid RM 520 million ($69 million) to buy three breweries and two brands from Weixue Beer Group, Henan’s second-largest brewer, in March. China Resources Snow Breweries, China’s largest brewer and a joint venture between China Resources Enterprise Ltd. and SABMiller, acquired Henan-based Lanpai Brewery in July, after snapping up three Henan-based plants from Henan Aoke Beer Industry Company in January and Yuequan Beer in November the year before. China Resources Enterprise Ltd. announced the deal less than one week after it bought 49 percent in another Chinese brewer, Jiangsu DaFuHao Breweries Company, and 100 percent of Shanghai Asia Pacific Brewery Company from Heineken N.V. Belgium’s Anheuser-Busch InBev spent RM2.7 billion ($419 million) on a new manufacturing facility in Xinxiang, Henan, the same year. China Resources’ Snow Breweries’ general manager told local reporters the brewer was just getting going in Henan, indicating that more buyouts lie ahead.5

Henan’s large market, low costs, and connectivity make it a pivotal battleground in China’s beer wars. “Whoever can control Central Plains (Henan) will be able to dominate the whole market in China,” Song Yugang, deputy secretary general of the marketing committee of Henan’s association of distillers and wine makers, said.6

The flurry of activity in Henan illustrates how China’s booming beer market is zooming toward consolidation. The top three spots in China’s beer market are held by China Resources Enterprise Co. Ltd., which brews Snow, China’s top-selling beer, in a joint venture with SABMiller; Tsingtao, which is 27 percent owned by Anheuser-Busch; and Anheuser-Busch’s own brands. Those three companies held 46 percent of the beer market in 2010, according to Euromonitor. The next four contenders are local, including Beijing Yanging Brewery Group and Henan Jinxing Beer Group. Beijing Yanjing’s ambitions to take on the big boys in Henan illustrates that local players with more affordable brands intend to work hard to win key segments in the consolidation game.

BANKING AND TELECOM SECTORS DOMINATED BY ASIAN CHAMPIONS

The HHI shows that much of Asia’s banking sector has achieved a level of concentration that meets or beats key Western markets, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Spain. Thailand is on par with the United Kingdom and Spain, Malaysia outstrips France, Indonesia just surpasses the United States, and Singapore, Asia’s most concentrated market, beats them all. The telecom sector is as concentrated, if not more, than key Western markets. The exception is India, which is the most fragmented in Asia.

What’s more, Asian companies dominate these concentrated markets. Some of this can be attributed to trade barriers. The telecom and financial sectors were historically viewed as industries of national importance and remained sheltered from foreign competition until recently. Asian governments worked hard to encourage consolidation ahead of liberalization to ensure the optimum number of local incumbents remained in control of the market before foreign competitors came in.

The most interesting story, however, is the transformation of key Asian banks and telcos into dominant regional players. Companies like Singapore Telecommunications (SingTel), CIMB Bank, and Axiata Group have been able to capitalize on their understanding of the region—and its consumers—to carve out a strong position as a regional champion.

Singapore Telecommunications, for example, has become Southeast Asia’s biggest telecommunications company by acquiring strategic stakes in mobile operators across Asia, including India, Thailand, and the Philippines. SingTel owns Optus, Australia’s second-largest telecommunications company. (See “The Quest for New Markets” section in Chapter 3.) Likewise, Axiata Group, formerly Telekom Malaysia International, is moving quickly to establish itself as a regional competitor. Axiata owns controlling stakes in mobile companies in Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Cambodia and owns significant minority stakes in companies in India and Singapore.

Both of these companies have built a regional strength that beats Telenor and Vodafone, the most active global players in Asia. Telenor, which controls mobile companies in Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Thailand, claimed 100 million subscribers in Asia as of February 2011. That figure remains firmly in the shadow of regional powerhouse SingTel, which hit 416 million subscribers at the second quarter of 2011. Axiata weighed in with 168 million, as of March 2011. Both Asian telecommunications firms continue to hunt for more acquisition targets to further expand their regional market share.

Malaysian CIMB Bank has leveraged its strong domestic position to expand across Southeast Asia, bolstering organic growth with strategic acquisitions. (See “Regional Ambitions” sidebar in Chapter 3.) CIMB Bank, which aims to capitalize on the demand for regional banking services that will come when the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) becomes a free trade zone in 2015, continues to make acquisitions to cement its position as one of Southeast Asia’s dominant banks.

Asian banks are building competitiveness in other areas, such as investment banking, that have traditionally been the stronghold of their Western peers. Western investment banks that have ruled Wall Street, Frankfurt, and London for generations have dominated Asia as well. Asian companies that want to raise capital need access to global investors and have veered to global investment banks with connections and a track record. The experience foreign banks have at helping companies raise capital on global markets has put them in a better position to reap the rewards of Asia’s economic boom until now.

Local banks are fast building the expertise required to compete on equal footing on international exchanges. The investment banking subsidiaries of Chinese banks are proving they can raise the kind of capital needed to compete with the big boys. Ping An Securities and Guosen Securities earned the fifth and sixth largest amount of investment banking fees in Asia, excluding Japan, between January 1 and May 1, 2011, according to Dealogic.7 They beat out Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse, Citigroup, and J.P. Morgan. As Asia’s economies continue to lead global growth and the region’s consumers look for new ways to invest their money, local banks with access to local investors will continue to build muscle and clout.

THE EXCEPTIONS: SOME INDUSTRIES LIKELY TO BE DOMINATED BY GLOBAL PLAYERS WHILE OTHERS RESIST CONSOLIDATION

Our Asian endgame theory has some important exceptions. Global companies will dominate in a couple of key industries because these are high-capital expenditure industries or they face limited access to raw materials. Some will not consolidate because governments, for nationalistic reasons, will never cede control.

Consider the steel industry. The iron ore industry is consolidated, and three big companies produce around 80 percent of the world’s iron ore. That necessitates consolidation on a global level, and these global players will dominate Asia, too. Steel companies must become large to negotiate with suppliers in this powerful position. When you look at the value chain of any industry, you can make a call about where the profit will lie: When companies on one part of the value chain have an asymmetrical advantage because of a lock over customers or patent rights or control over raw materials, that group of companies drives the price. In the steel industry, the value lies in the hand of the iron ore companies. The steel companies that can survive and make a profit in a situation like this are the large ones or integrated steel companies that have downstream capabilities and can supply their own iron ore.

The concentration of the iron ore sector has driven global consolidation in the steel industry. China, which prohibits foreign companies from taking controlling stakes in its steel industry, remains the exception. Even there, the Chinese government is attempting to drive consolidation of its domestic industry to better negotiate with the big iron ore majors. China’s steel industry acts as a collective in negotiating iron ore prices to achieve the same effect. There are thousands of steel companies in China, and the government has indicated it wants 10 of them to produce 50 percent of the country’s volumes. In 2010, the government of Hebei, China’s top steel-producing province, announced it planned to whittle the number of steel mills from 88 to 10 within five years and would cut electricity and deny credit to companies that refused to participate in consolidation.8

Asia’s auto sector is another that global companies will dominate. The world’s auto industry is gripped by over-capacity, over-supply, and high-capital expenditure costs as continual research and development is needed to keep up with consumer tastes: Consolidation will continue as carmakers look to spread their high development and production cost over a larger customer base, and it will be led by the few that can afford it. When it comes to cars, consumers across the world do have common tastes, usages, and preferences, unlike other products, such as beer and soft drinks.

Though these industries do prove an exception to our local optima theory, it doesn’t mean Asian companies won’t emerge as global champions of these sectors. Many existing global champions are local. Indian-born Lakshmi Mittal’s ArcelorMittal is the world’s largest steel company. During some periods in the recent past, Japanese automaker Toyota produced more cars than any other; and China’s Geely, which bought Volvo from Ford in 2010 and plans to increase China sales fivefold by 2015, is a fast-moving contender for an Asian champion role.

Other industries that are deemed to be of national interest will remain local because governments will make sure of it. The oil and gas industry is one example, and airlines are another.

The upstream oil sector can be divided into three categories: international oil companies (IOCs), which includes the six oil majors that dominate the business; national oil companies (NOCs), such as Malaysia’s Petronas and Indonesia’s state-owned equivalent, Pertamina; and oil support service companies that do everything from exploring and drilling to providing support services to the NOCs and IOCs. At the start of the century, IOCs controlled the industry. They came to less developed countries, extracted the oil, and left. Local governments got wise to this and decided to get in the game and keep some of that wealth at home. During the 1960s, a wave of nationalization created NOCs that became competent players in their own right. IOCs are able to collaborate with NOCs, but typically regulations exist to ensure NOCs can displace the local incumbent. That picture is going to stay static. We do foresee that NOCs may buy up support service companies, but this industry will not see a fundamental shift.

The story is similar with airlines. The airline industry is a high-capital expenditure industry, and the more flights and higher connectivity (i.e., the number of routes globally) an airline has, the more a network effect kicks in, leading to lower unit operating costs. This means that the natural evolution for this industry is toward a few large airlines dominating the skies. In reality, we have plenty of national flag carriers typically owned by the government, which won’t let them go broke no matter how much trouble they’re in, as they are viewed as a source of national pride or are needed to serve low-population centers. As a result, airline capacity is an oversupply in the market. In addition, low-cost airlines, typically run by private shareholders, such as AirAsia, are becoming cost competitive, making life even more difficult for national carriers. No national full-service carriers in Asia are making money, except Singapore Airlines. AirAsia, which is profitable, was recently allowed to take a stake in state-owned Malaysia Airlines (MAS) as a way to rationalize the sector. Hong Kong-based Cathay Pacific, the region’s other profitable full-service airline, is not state-owned and serves as proof that governments could step away from this industry and let it fly its own course.

THE CONSOLIDATION TREND IN ASIA: SAME DRIVERS, DIFFERENT OUTCOMES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following A.T. Kearney document was used as background material for this chapter: “Merger Endgame Phases” by Jürgen Rothenbücher, a partner and head of the firm’s strategy practice in Europe, and Joerg Schrottke, a partner in our Munich office and member of the firm’s strategy practice. The authors provided the original framework that was modified for this book.

Notes

1. CIA World Factbook.

2. Euromonitor International, Retailing in China, January 2011, 12.

3. “gRetail Global Expansion: A Portfolio of Opportunities,” The 2011 A.T. Kearney Global Retail Development Index, www.atkearney.com/index.php/Publications/retail-global-expansion-a-portfolio-of-opportunities2011-global-retail-development-index.html.

4. “China Resources Could Buy Jiangxi Retail Asset, Accelerates Development of Retail Business,” Business China, March 30, 2011, http://en.21cbh.com/HTML/2011–3–30/3MMjUwXzIwOTc3Mg.html.

5. “CR Snow Breweries Buys Henan-Based Brewer for 3rd Time, Gearing Up for Local Market,” Business China, July 23, 2011, http://en.21cbh.com/HTML/2011–7–23/xMMjUwXzIxMDYxMA.html.

6. “Henan’s Last Independent Brewer Waging Lonely Battle,” Want China Times, March 10, 2011, www.wantchinatimes.com/news-subclass-cnt.aspx?cid=1202&MainCatID=12&id=20110310000080.

7. Michael Shari, “Asia’s Banks on the Fast Track,” Global Finance, June 2011, 23.

8. “China’s Hebei to Launch Steel Consolidation Drive,” Reuters, November 4, 2010, www.reuters.com/article/2010/11/05/china-steel-consolidation-idUSTOE6A401K20101105.