CHAPTER THREE

The Rise and Rise of Cross-Border M&A

Over the past decade, several attention-grabbing Asian cross-border M&A deals have occurred. What has been surprising is that they have been done before these firms consolidated their local markets. We will explore the drivers behind cross-border deals and suggest this trend will increase. We will explore the added complexity that cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A) bring to deals and how firms will have to work harder to extract full value.

Asian companies have taken the standard M&A metrics that have long governed who buys what and when, and thrown them out the door. We have witnessed a sharp rise in cross-border merger activity in many Asian industries before domestic consolidation has begun. Young, aggressive Asian corporations are moving forward more quickly than you’d expect given the state of development of Asia’s economies, and these corporations are snapping up companies in other parts of the world. China’s fledgling automotive sector, for example, has more than 100 players and has many rounds of consolidation ahead. Geely, for one, decided not to wait. In 2010, the Hangzhou-based company, which makes its own brand of mid-sized, mid-tier cars, paid $1.8 billion for Volvo, one of the world’s best-known auto brands.

The kinds of Asian companies that are driving cross-border M&A are surprising. They’re not the type of world-beating champions that led global mergers during the 1980s and 1990s but instead are often mid-sized companies with smaller balance sheets and little experience of M&A in their own domestic markets. These acquisitive companies are proving that size and experience don’t always matter. Companies such as Tata and Geely are breaking the mold as they move swiftly to snap up the assets they need to leapfrog competitors, access new markets, and move up the technology and branding curve.

TATA TEA LEADS GLOBAL ACQUISITION CHARGE

Tata Tea’s takeover of the hallmark British Tetley Tea brand in 2000 was dubbed “the acquisition of a global shark by an Indian minnow” by India’s media. That minnow has quickly moved to the top of the food chain.

Tata Tea was a small, $114 million company that sold commodity tea. Its target, Tetley, was the world’s second-largest producer of tea bags and an iconic tea brand that was three times its size in terms of revenue. The move transformed Tata Tea from a farming operation that ran tea plantations to a high-margin global distributor of teas and other beverages.1 After the acquisition, Tata Tea exited the commodity tea business and sold its vast plantations—the majority to its own former employees—to concentrate on its new, higher-value added, consumer-focused business model.

Tiny Tata Tea outbid global heavyweights, including Nestlé and Sara Lee, for Tetley. The tea brand had suffered from rapidly shrinking demand in its core U.K. market, which is steadily switching to coffee, and stiff competition from rivals like Brooke Bond.2 Tetley’s pretax profit fell to £4.98 million in the year ended March 1999 from £35.7 million the year before.

The headline-grabbing merger was the largest cross-border takeover of an international brand by an Indian company. “It is a bold move and I hope that other Indian corporates will follow,” Tata Group chairman Ratan Tata said.3

They certainly did. In the past decade, Indian companies, including Tata, Bharti Telecom, and Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries have snapped up stakes in companies in nearly every industry, from steel and textiles to telecommunications and auto manufacturing. The Tata Group, which operates in a range of businesses, has led the charge.

In 2004, the Tata Group hired Alan Rosling, chairman of Hong Kong’s Jardine Matheson Group and a former director of a Jardine-Tata automotive joint venture, to come on board as an executive director in charge of acquisitions. Rosling designed an M&A strategy that transformed Tata into a global name.

That year, Tata Motors bought Korea’s Daewoo Commercial Vehicle Co. for $100 million. In 2007, Tata Steel acquired the Anglo-Dutch steel giant Corus Ltd. for $12.1 billion; Tata’s Indian Hotels Ltd. paid $134 million for the Ritz-Carlton hotel in Boston the same year and renamed it the Taj Boston. In 2008, Tata Motors spent $2.3 billion to buy Jaguar Land Rover from Ford Motor Company.

The acquisition spree prompted some criticism from stock market analysts, many of whom felt the company paid too much for Jaguar Land Rover and worried it had leveraged itself too high, too fast. The timing of some of its overseas purchases, particularly the Corus and Jaguar Land Rover deals, was far from ideal: The 2008–2009 global financial crisis hit both industries hard. Global steel prices fell nearly 40 percent during the peak of the crisis, and auto sales in Europe practically stalled.

The economic recovery, however, has brought vindication. By mid-2010, both Corus and Jaguar Land Rover had turned around. Jaguar Land Rover accounted for nearly 70 percent of Tata Motors’ net profit and 60 percent of its revenues in the quarter ended June 2010. Tata Steel, meanwhile, reported a major improvement in profitability in the second half of 2010; the company said in a statement that results were enhanced “by the dramatic turnaround” of Tata Steel Europe, which reported a positive earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) of $513 million compared to an $813 million loss during the first half of 2010.

The outlook for the tea business has also improved. Tata Tea, which renamed itself Tata Global Beverages in 2010, has seen sales grow by about 20 percent each year for the past three years.

The total revenue of all the Tata companies, taken together, was $67.4 billion in 2009–2010, with 57 percent of this coming from business outside India, according to the company’s website. This represents a 548 percent increase in revenue since 2001–2002, the start of the company’s global push.

At the time of the Tetley takeover, Tata’s Krishna Kumar, now chairman of Tetley Tea, said: “If you want to be a strong player, you can’t not be a global player.”4 That seems to have turned into something of a corporate motto at the Tata Group.

We are seeing this trend play out in our own practice at A.T. Kearney. Most of our Asian clients have grown rapidly in the past five years, and they’re concerned about the ability of organic growth to continue to deliver the same kind of returns. The companies we deal with are putting more thought and effort into building an M&A strategy: They’re talking to more bankers, considering more deals, and setting up their own internal departments to find and flesh out potential M&A.

Asia’s fast rebound from the 2008–2009 global financial crisis added fresh momentum to the region’s cross-border acquisition trend. Asia wasn’t as hard hit as the West, and the region’s economies and stock markets recovered far more quickly. Asia is driving global growth, and Asian companies have more cash, more confidence, and stronger balance sheets than many of their global peers. They’re in a position to buy, and they want a big bang for their buck.

THE NUMBERS POINT EAST

The sharp rise in Asian outbound M&A underscores how active Asian companies have become on the global stage.

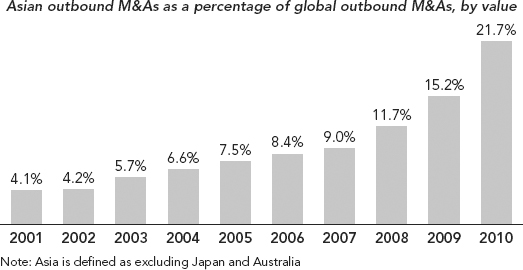

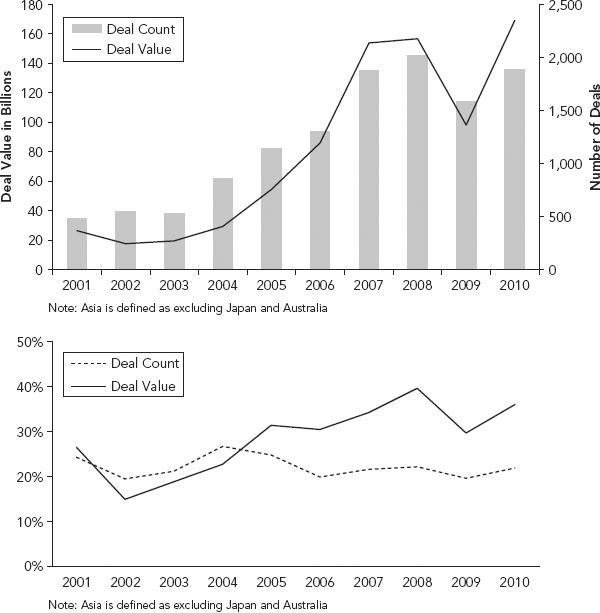

Asia’s share of the world’s total number of cross-border M&A has more than quintupled in the last decade (see Figure 3.1). Asian acquirers did $169 billion worth of cross-border deals in 2010, which accounted for 22 percent of global outbound M&A, up sharply from Asia’s 4 percent share in 2001, according to data from Dealogic.

We excluded Japan and Australia from our analysis to get a clearer picture of the cross-border trend in emerging Asia. For cultural or geographic reasons, these developed countries traditionally have had lower cross-border transactions.

Asian companies did 1,887 cross-border deals to hit that $169 billion mark in 2010, up sharply from 490 deals worth $26 billion in 2001, according to data from Dealogic (see Figure 3.2). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions represented 36 percent of all Asian M&A value in 2010.

FIGURE 3.2 (a) Asian Cross-Border M&A and (b) Asian Cross-Border M&A as a Percentage of Total Asian M&A

Source: Dealogic; A.T. Kearney analysis.

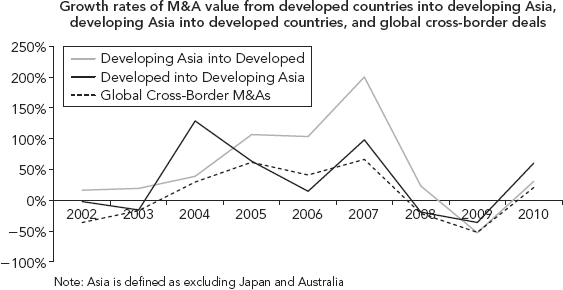

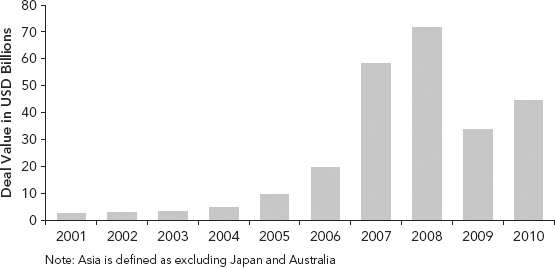

Asian companies are not just acquiring companies in other parts of the region; they are increasingly eyeing up assets in developed countries. The value of deals that involved an Asian company making an acquisition in a developed country grew from $2.4 billion in 2001 to $44 billion in 2010, as shown in Figure 3.3.

FIGURE 3.3 Acquisitions by Asian Companies in Developed Countries

Source: Dealogic; A.T. Kearney analysis.

Though the value of acquisitions of Asian corporations by companies from developed nations has grown over the past decade, the reverse—Asian companies buying in developed countries—has grown the fastest (see Figure 3.4). This reflects the fact that Asian companies emerged relatively unscathed by the recent financial crises and well-positioned to take advantage of undervalued assets in developed countries.

China and India are spearheading these acquisitions. The two giants accounted for 60 percent and 19 percent, respectively, of the value of the deals done by companies from developing Asian countries in developed markets in 2010, according to data from Dealogic.

What is interesting, however, is that Malaysia came in at a surprising third at 13 percent. (In 2009, Malaysia even inched out India, ranking second place that year.) A key factor here is that oil-producing nations such as Malaysia and the Gulf countries, and high-growth economies such as China and India, have gained large current account surpluses and are looking to diversify into global assets to reduce currency volatility and stabilize their economies. Given that China has $2.13 trillion in currency reserves that can be deployed, developing countries are going to have a dramatic effect on corporate configurations.

THE DRIVERS BEHIND ASIA’S CROSS-BORDER M&A BOOM

Companies in developed markets typically pursue M&A as a way to cut costs, to strengthen their competitive positions, or to broaden their presence in high-growth markets. They are constantly on the lookout for acquisitions with growth prospects, and they’re interested in manufacturing and sourcing targets in low-cost environments to strengthen their competitive position.

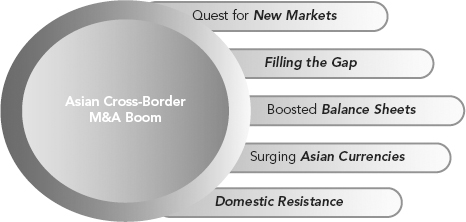

Emerging-economy acquiring companies, on the other hand, often see M&A as more of a leapfrogging exercise. For young Asian companies seeking to become global players, M&A offers a shortcut to the markets, distribution networks, brand names, and new technologies they need (see Figure 3.5). These firms are entering established markets to maximize the advantages of their low-cost structure against traditional competitors. The expansion strategy of these companies is more focused on broadening the customer base and increasing market share. Other important drivers of cross-border M&A are Asia’s increasing access to government support, global capital to finance its purchases, and its strengthening currency.

The Quest for New Markets

Singapore Telecommunications (SingTel) and Indian outsourcing firm Infosys Technologies are from two different countries and industries. The same driver, however, underpins the M&A strategies of these two companies: access to new markets.

Tiny Singapore offers few growth prospects for national telecommunications company SingTel. Competition from other players is stiff. SingTel, like other Singaporean companies, had no choice but to expand beyond its own shores.

The company started buying stakes in mobile phone companies around Asia in the 1990s, including Globe Telecom in the Philippines and Advanced Info Service in Thailand. In 2000, it paid $400 million for a 20 percent stake in India’s Bharti Telecom and a 15 percent stake in Bharti Televentures; at the time, the deal represented the largest foreign investment in India’s telco sector. The year 2001 was a particularly busy one for SingTel: It paid $7.3 billion for Optus, the second-largest phone company in Australia, and went on to buy a 22.3 percent stake in Indonesia’s Telkomsel.5 The Optus deal helped turn SingTel into one of the region’s biggest telecommunications companies and the largest in Southeast Asia. After that acquisition, SingTel began generating more than half its revenues outside of Singapore.6

REGIONAL AMBITIONS

Strengthened by the success of its first round of regional acquisitions, CIMB Group, Malaysia’s second-largest lender, has mapped out a plan to turn itself into one of Southeast Asia’s top three regional banks.

The group, currently the fifth-largest lender in Southeast Asia, hopes to hit a top-three position by 2015. The company plans to continue along the acquisition trail to achieve that goal. “I do foresee over this period to 2015, we’ll do more M&As to grow,” CIMB’s Group Chief Executive, Dato’ Sri Nazir Razak, told reporters in April 2011.7

CIMB is particularly interested in acquiring a bank in the Philippines, where it has yet to build a presence, Razak indicated. The company would consider a second acquisition in Thailand, one of the bank’s fastest-growing markets.8

CIMB was a relatively minor bank until 2005, when it acquired Bumiputra-Commerce Group, a large Malaysian lender. In 2008, CIMB merged its Indonesian unit, PT Bank CIMB Niaga, with PT Bank Lippo, and the unit became Indonesia’s sixth-largest bank. CIMB acquired BankThai PCL that same year, expanding its presence in another core Southeast Asian market.9 In 2009, it took a 19.99 percent stake in Bank of Yingkou Co. Ltd, becoming the largest shareholder of the bank, itself the largest bank in the city of Yingkou, China.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) plans to drop trade barriers and become a single market by 2015. CIMB is betting its Southeast Asian push will position the bank to capitalize on that enlarged, free trade economy. When the free trade plan goes ahead, a growing number of companies will want banking services that span the 10-nation region. ASEAN nations have a combined population of 600 million and a combined economic output of $1.2 trillion.10

CIMB has operations in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and Brunei, with more than 1,100 branches throughout the region. The company has applied for banking licenses in Cambodia and Vietnam.

The Malaysian bank’s regional foray has paid off so far. About 30 percent of CIMB’s earnings come from non-Malaysian operations, according to Citigroup. The bank has posted record profits in several of the past five years, and its market capitalization surged to $14 billion from $3.3 billion between 2005 and 2010, making it one of the fastest-growing banks in the region.11 CIMB Group Holdings’ revenue has soared to 11.8 billion ringgit ($3.88 billion) in 2010 from 601 million ringgit in 2004, before its regional push.

The company’s investment and Islamic banking units have become strong brands in their own segments. CIMB Islamic Bank, a major player in shariah banking, has been the world’s biggest underwriter of sukuk, or Islamic bonds, since 2006. The company’s investment bank, CIMB Investment Bank Bhd., has offices in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Thailand, Brunei, the United Kingdom, and the United States. CIMB, which bought Singapore broker G.K. Goh in 2005, struck a deal in 2010 to take a 10 percent stake in VFC Securities, a Vietnam-based brokerage, with an option to increase its shareholding to 40 percent.

When the company announced its quarterly earnings in February 2003, then-CEO Lee Hsien Yang reported that SingTel’s acquisition spree had decoupled its growth trajectory from the Singapore market. “I am happy to report that our results today demonstrate the success of our regional expansion strategy,” he said in a press statement. “Our results in Australia and the strong performance of our other overseas investments mean that we have significantly reduced our dependency on our Singapore operations to maintain earnings growth.”12

SingTel has since upped the stakes it owns in many of these overseas companies, including Bharti Telecom, Globe Telecom, Indosat, and AIS. It has bought stakes in Pacific Bangladesh Telecom and Warid Telecom, in Pakistan. All told, SingTel has invested around S$7.5 billion in overseas investments.13

It has not always been smooth sailing. SingTel’s foray into Indonesia, through Telkomsel, was complicated by the presence of Temasek, the investment arm of the Singapore government, in the same sector. Temasek is SingTel’s largest shareholder and owns ST Telemedia, which took a 41 percent stake in Indosat, another Indonesian telco. In 2007, Indonesia’s antitrust watchdog said it found Temasek guilty of engaging in monopolistic and anti-competitive behavior in Indonesia’s cellular market through Telkomsel and Indosat. The case dragged on in court for years, and in 2010, Temasek lost its appeal. Indonesia’s Supreme Court ruled that Temasek and nine parties, including SingTel, each had to pay a S$2.3 million fine.14

Still, SingTel plans to stay the course. The company’s current CEO, Chua Sock Koong, said in 2010 that SingTel is looking for acquisitions in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, to boost growth.

Infosys doesn’t have the constraints of SingTel’s tiny home market. The world is the market for a company like Infosys that provides global outsourcing services, and Infosys, India’s second-largest outsourcing firm, earns more than 60 percent of its revenue from the United States. Still, the company is looking at new ways to expand its reach into the United States and other markets. In 2009, Infosys BPO bought Atlanta-based McCamish Systems, a company that provides back-office business process solutions for insurance and retirement companies. The company’s CFO said in February 2011 that Infosys plans to spend up to $200 million to acquire companies in the United States so it can bid on government contracts.15

The company is hunting for acquisitions in Europe and Japan in areas including healthcare and public services. “We are doing acquisitions for strategic fit and adding capability at this point in time,” Infosys CEO S. Gopalakrishnan told Reuters in May 2011.16

Still other Asian companies see M&A as a quick way to access new emerging markets like Africa. India’s Bharti Airtel paid $10.7 billion to acquire the African assets of Kuwait’s Zain Group in 2010. The deal, one of the biggest acquisitions of the year, turned Bharti into the world’s fifth-largest telecom firm, with operations in 18 countries.17 Bharti’s chairman and founder Sunil Mittal described the acquisition of Zain Africa as “a game changer” for the company.

“With this acquisition, Bharti Airtel will be transformed into a truly global company,” said Mittal in a press statement.

Taking the M&A route gave Bharti a big-bang entry into Africa’s fledgling telecoms market since expanding organically into each country and obtaining coveted licenses would have taken years. Zain Africa has 42 million subscribers in 15 African countries and annual revenues of $3.6 billion, providing Bharti with a strong start. Bharti aims to grow to 100 million subscribers and $5 billion in revenue by 2013.18

Mittal had been working hard to get into Africa: The Zain deal was his third attempt to crack the continent. Two earlier bids to pull off a merger with MTN, a South African telecom company, fell apart after months of negotiations.19

The company plans to transplant the successful low-cost model it developed in India to Africa, which Mittal described in a press statement as “the continent of hope and opportunity.”

Many Asian companies, like Bharti, have built their business model on serving the middle- to low-end consumer sector in their own emerging market at home, a skill many Western conglomerates are scrambling to acquire. Decades before companies like Nokia began making low-cost, durable phones with an extra-long battery life to tap India’s rural markets, India’s CavinKare was selling tiny, affordable sachets of soap and shampoo in the country’s most remote nooks. Companies like CavinKare wrote the book on rural and “bottom of the pyramid” marketing well before Western companies started looking beyond the city limits. Multinationals that came to Asia during the 1990s typically stuck to the middle to high ground, and have only shifted their focus to the large, untapped lower end of the sector in the last few years. A range of Asian companies, cutting across almost every industry, has figured out how to design, distribute, and market products for the region’s large numbers of mid- to low-income consumers.

Bharti, for one, built its large market share by providing affordable mobile phone products and services to India’s vast rural hinterland, and consumer companies from China, India, and other Asian countries will likely follow its push into Africa.

Bharti had something to sell to Africa that worked in its own emerging market back home, but important push factors existed, too. About 15 million new subscribers are signing up each month for mobile phone services in India, making this the fastest-growing wireless market in the world. That’s attracted new foreign competitors like Sistema and Telenor. Intense competition, from local and foreign players, has driven down call charges in India, squeezing margins and earnings growth.20

The fact that Bharti, the leading telecommunications company in the world’s fastest-growing market, feels compelled to seek other new, emerging markets to ensure growth underscores the upward trajectory of Asia’s cross-border M&A trend. More companies are going to contemplate similar strategies as pressure mounts to maintain profit margins.

Filling the Gap: Acquiring Access to Distribution, Brands, New Technologies, and Resources

M&A has proven a powerful tool for Asian companies seeking to build a global brand. Consider Lenovo’s acquisition of IBM’s personal computer (PC) business. Until 2005, Lenovo was unknown outside China. It had tried to branch out into new products and markets only to beat a hasty retreat after losing market share in its core markets. With the acquisition of IBM’s PC business, however, it found access to more than 100 foreign markets and became a major global player overnight instead of struggling for years in the intensely competitive industry. As part of the deal, Lenovo gained the rights to the “ThinkPad” brand, which continues to dominate the PC market.

By marrying IBM’s efficient supply chain and distribution network with a low-cost manufacturing base, the deal was underpinned by sound industrial logic. The merger integration had its share of challenges, but after two years of perseverance, the combined entity showed blazing results in 2007.

China’s rise as a manufacturing power was driven by low production costs and low product prices, but if Chinese companies want to persevere in the face of growing foreign competition, they need to close the technology and brand gap. Chinese companies aren’t alone in this respect: Many Asian manufacturing companies failed to invest in innovation or branding, choosing instead to rely on low prices to drive volume sales. As margins continue to fall, more Asian companies are thinking about how to move up the value chain.

Lenovo’s executives acknowledged that the play for IBM was motivated by the realization that their grip on their home market is vulnerable.21 The company’s products were being squeezed at the high end by the likes of Dell and at the low end by cheaper local competitors. “We are losing our brand advantage in China’s domestic market,” Liu Chuanzhi, then Lenovo’s chairman, said in a 2004 interview in the Beijing-based Xinjing newspaper. “We seek to build an internationally recognized brand, which will require plenty of courage and capital.”22

Some Asian companies that have managed to build a strong brand at home are using M&A as a tool to get better access to technology and distribution and to boost the profile of their homegrown brand on the global stage.

Tata, one of India’s more acquisitive conglomerates, achieved all three goals when its automotive unit bought the Jaguar and Land Rover brands. In March 2008, Mumbai-listed Tata Motors paid $2 billion for Jaguar Land Rover from Ford Motor Company, which needed to restructure its own business to return to profitability. The deal initially raised eyebrows: Tata had built its business making small, inexpensive cars for the Indian market. It had no experience making or managing a luxury brand like Jaguar.

Not everyone took that view. When the deal was announced, Tom Purves, who was then CEO of BMW North America, described Tata as “probably the best possible owner for Jaguar and Land Rover.”23 Tata was an experienced and profitable automaker, he noted. North America’s own stable of carmakers, meanwhile, have struggled in recent years in the face of competition from Japanese and Korean automakers. “Actually, they are probably the only company that could come in and do this,” Purves added.

For Tata, the deal brought two big-name brands into its stable, giving the Indian automaker an opportunity to move its portfolio up the value curve. It gained access to a top-end automotive design and engineering operation. Tata, meanwhile, infused cash and emerging-market know-how into the business.

In May 2010, the company announced plans to build Jaguar and Land Rover cars in China to cut costs and expand sales of both brands in emerging markets. In the meantime, the company opened more showrooms in India and set up a sales company in China.24 That effort quickly paid off. In February 2011, Tata Motors reported a nearly fourfold rise in its third quarter consolidated net profit, led by higher sales at its U.K.-based Jaguar Land Rover business and at home. Jaguar Land Rover’s sales, which had taken a dip during the global financial crisis when consumers in Europe and the United States reined in spending, began to recover in 2010, partly as a result of expanded sales in China, the company reported.25

M&A offers Asian companies a quick way to build up their distribution reach. Japanese beverage company Kirin Holdings spent about 1 trillion yen between 2006 and 2010 on M&A to expand its reach into Asia. The company, which owns Australian dairy firm National Foods and Australian brewery Lion Nathan, and a 48 percent stake in Philippine beer company San Miguel, took a 14.7 percent stake in Singaporean beverage company Fraser & Neave (F&N) in 2010 for $953 million, making it F&N’s second-largest shareholder. F&N is the largest beverage company in Malaysia and Singapore. It bottles and distributes Tiger, Anchor, and Heineken beer through Asia Pacific Breweries, a joint venture between F&N and Heineken N.V., and is the regional anchor bottler for Coke, through F&N Coca-Cola. F&N, which makes its own brands of fruit and soft drinks, has operations in Thailand, Vietnam, and China.

Kirin’s executives said the company planned to use F&N’s extensive sales network in Southeast Asia to expand its distribution, citing dairy products from its National Food subsidiary as an example of its distribution-expansion goal.26 “This deal will give us a base in Southeast Asia, an area where we have been weak,” said Hirotake Kobayashi, Kirin’s managing director. “The stake is small, at 14.7 percent, but it is strategically important.”27

In August 2011, Kirin struck further afield, spending $2.57 billion to acquire slightly more than 50 percent of Schincariol, Brazil’s second-biggest beer brewer. The acquisition was the third largest ever done by a Japanese company, after Takeda Pharmaceutical’s $14 billion purchase of Nycomed. Kirin later stepped in and bought the remaining 50 percent, making it the full owner of the Brazilian brewer. That deal further underscored the push factor for many Japanese companies, who face a dwindling market at home. Industrywide beer shipments in Japan fell 3.5 percent in the first half of 2011, according to an August 3, 2011, report by the Wall Street Journal. In 2001, Japanese brewers were among world’s most acquisitive companies, snapping up $4 billion in deals in the first eight months of the year, the report said.

Tata gained production and distribution reach, and a technology boost, when it bought Corus Steel, Europe’s second-largest steel producer, in 2007, for $12 billion. Through that deal, Tata acquired production sites in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Germany, France, Norway, and Belgium, giving it a strong European presence to balance its Asian operations. Tata Steel has operations in Thailand and India, and a stake in Singapore’s NatSteel. The acquisition of Corus helped Tata Steel up its technology game: Corus has particularly strong research and development (R&D) and product development capabilities for value-added products in the global construction, packaging, and automotive markets.28

Other Asian companies are acquiring global assets to supply raw materials and energy to their own home market. Chinese companies, hungry for resources like coal and oil to fuel economic growth back home, are leading this charge, snapping up stakes in resource companies from Australia and Africa to South America.

In 2010, China Petrochemical Corporation (also known as Sinopec Group) paid $7.1 billion for a 40 percent equity stake in oil and gas company Repsol YPF Brasil SA, China’s largest single outbound deal of the year. Yanzhou Coal made China’s largest-ever investment in Australian resources when it paid $3 billion to take over Felix Resources in 2009.

Indeed, China accounted for nearly two-thirds of Australia’s US$10.6 billion mining M&A deals in 2009, up from 13 percent in 2008, according to Ernst & Young. The global financial crisis, which choked off access to debt and capital for mining and metal companies in Australia and other parts of the world, paved the way for China’s push into Australia’s mining sector.29

Asian resource companies have focused on Africa. State-owned Jinchuan Group Ltd., China’s largest platinum producer, penned a deal to take over Johannesburg-based Wesizwe Platinum Ltd. in December 2010. The deal includes a debt commitment, giving Wesizwe $877 million to build its first mine in South Africa, the world’s largest supplier of platinum. China Guangdong Nuclear Power Group of Shenzhen, the nation’s second-largest reactor builder, made a $1.2 billion bid for London-based Kalahari Minerals Plc. in March 2011. That deal, if it goes ahead, will give the state-owned company access to Perth-based Extract Resources Ltd.’s Husab uranium project in Namibia. Kalahari owns about 43 percent of Extract.30

The value of M&A transactions in Africa surged to a record high of US$44 billion in 2010, more than double the US$17.5 billion worth of deals done in 2009, and China and India accounted for 36 percent of the value of all transactions, according to a report by Deloitte.31

Boosted Balance Sheets: Asia’s Stock Markets and Governments Underwrite the M&A Boom

Asia’s booming stock markets have provided companies with the means to go on global shopping sprees. The region’s governments, meanwhile, are doing everything in their power to encourage the trend—including giving out low-interest loans.

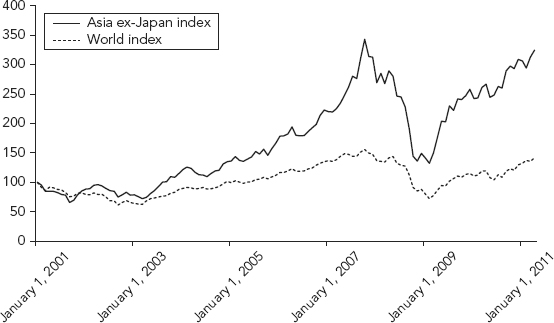

Since the late 1990s, Asia’s stock markets have outperformed their peers, churning out billionaire businessmen like Ratan Tata, who have the confidence to fulfill their increasingly global ambitions (see Figure 3.6). Many companies across Asia have a higher price-earnings multiple than their global peers. Globalization, meanwhile, has given more Asian companies access to global capital. Bankers are beating a path to Asia’s corporate offices, hoping to profit from the region’s economic boom. Investors in the most rural parts of the United States are putting money into the most remote parts of Asia. The world is focused on Asia’s growth story. Share prices are up, and appetite is strong for Asian equity and debt. Indeed, Asia’s share of global stock issuance has doubled in the last decade. Asia’s equity offerings comprised 41 percent of the world’s equity offerings in 2010, up sharply from 18 percent in 2001, according to data from Bloomberg. It’s easier than ever for Asian companies to raise the money they need to go global.

Consider how quickly and easily Tata Motor was able to restructure and repay the loans it took to buy Jaguar and Land Rover. In October 2009, Tata raised $750 million in a combined shared placement and convertible bond issue that allowed the company to repay the remainder of the bridge loans it had taken out to buy Jaguar and Land Rover the year before. Demand for the issue was so high that Tata, which had initially planned to raise $300 million from each issue, increased the size of each tranche to $375 million. The strong response to the issue, which took place in the depths of the global financial crisis, highlighted the strength of demand from international investors for Indian assets.32

Asian governments, meanwhile, are encouraging cross-border M&A to diversify their own markets and economies. Some governments are putting state money where their mouth is. China, for one, is sitting on more than $2.5 trillion in foreign reserves and is actively spending some of that cash for global acquisitions.

China’s $300 billion sovereign wealth fund, China Investment Corp. (CIC), which was set up in 2007, has stakes in a range of companies, including Morgan Stanley, U.S. private equity firm Blackstone Group, Singapore-listed commodities supply chain manager Noble Group and Canadian oil and gas company Penn West Energy. The fund holds sizeable stakes in a number of China’s major state-owned banks. In April 2011, the Financial Times reported that the Chinese government may provide CIC with another $100 billion to $200 billion to reduce its exposure to U.S. government debt.

China’s premier, Wen Jiabao, said in 2009 that Beijing intends to use those foreign exchange reserves—the largest in the world—to support and accelerate overseas acquisitions by Chinese companies. “We should hasten the implementation of our ‘going out’ strategy and combine the utilization of foreign exchange reserves with the going out of our enterprises,” he said.33 That comment was the first official articulation of Beijing’s intention to support Chinese corporations’ bids to buy offshore assets. One way to do that is for CIC to take stakes in Chinese companies listed offshore or to beef up stakes in companies that are investing overseas.

Private and state-owned Chinese companies have become active global acquirers. Outbound M&A grew 49 percent, by value, to $44 billion in 2010 over the year before, according to Dealogic. Public capital, meanwhile, is increasingly being used to fund those cross-border acquisitions. The China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), for example, announced in 2009 that it had received a low-interest $30 billion loan to fund its overseas acquisition spree. “The credit agreement is of great importance for CNPC to speed up its overseas expansion strategy and secure the nation’s energy supplies,” the company’s chairman, Jiang Jiemin, said in a statement.34

Sweet deals like this underscore China’s commitment to spend what it takes to ensure its enterprises can acquire the resources the country needs.

Surging Asian Currencies Support Spending Spree

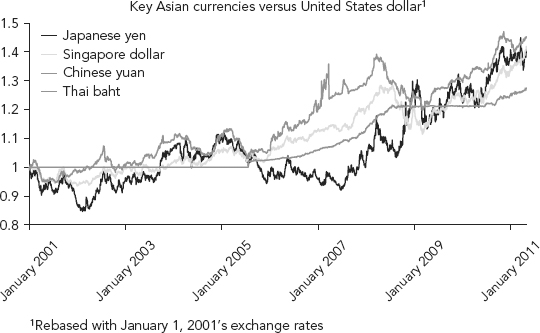

Stronger Asian currencies have given Asian companies much bigger purchasing power. Consider the yen, which, in August 2010, hit a 15-year high against the dollar. Faced with a shrinking domestic market and bolstered by the stronger yen, a wide range of Japanese companies began looking for M&A opportunities that year to help them tap into new growth markets abroad.35

One such company was Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corp. (NTT), which agreed in July 2010 to pay $3.2 billion for South African technology service provider Dimension Data. The two companies actually began talks in 2009 but parted company because they were too far apart on price. They returned to the table a year later, after the yen had surged against the dollar. The same deal, at the same price proposed by Dimension, had become 10 percent cheaper for NTT.

In 2011, the bargain hunting continued at breakneck speed. According to Dealogic, outbound M&A by Japanese companies hit $34.7 billion in the first five months of the year, outstripping the $34.2 billion achieved in the whole of 2010. Headline deals included Takeda Pharmaceutical Co.’s $13.7 billion purchase of Swiss drug maker Nycomed. That deal, announced in May, was the second-biggest overseas acquisition ever by a Japanese company.36 The same month, Toshiba Corp. announced it had agreed to spend $2.3 billion to buy Swiss meter maker Landis+Gyr.

Stronger domestic currencies were one of the key drivers behind Asia’s 2010 M&A boom. Currencies like the Thai baht, the Indonesian rupiah, and the yen strengthened sharply against the dollar, sparking a wave of cross-border M&A.

In July 2010, ThaiUnion Frozen became one of the world’s largest canned tuna firms, by sales, when it bought French canned seafood business MWBrands (MWB) for €680 million ($884 million). MWB owns brands like John West, Petit Navire, and Mareblu. ThaiUnion owns Chicken of the Sea. Backed by a strong baht, ThaiUnion beat out well-known private equity firms like the Blackstone Group to secure the deal.37

Stronger Asian currencies also provide a cushion for Asian companies. Mergers often fail because companies pay too much of a premium, notes Wharton management professor Lawrence G. Hrebiniak in a recent report. The rise in value of the region’s currencies defrays some of that risk by providing relative bargains (see Figure 3.7).

FIGURE 3.7 Rising Asian Currencies Allowing Asian Acquirers to Buy on the Cheap

Source: Factiva; A.T. Kearney analysis.

Asia’s strong reserves will likely continue to buoy local currencies. That means companies on the lookout for global acquisitions will get a bigger bang for their non-U.S. buck, adding yet more momentum to the M&A trend.

Domestic Resistance to Merger Pushes Companies beyond Their Borders

Some Asian companies look for acquisitions outside their own borders because it’s just too difficult to land a deal at home. Many Asian companies are linked to governments or family owned, and often majority shareholders don’t want to sell out, even to a good offer. Some even opt for deals that may not deliver the best price.

Asian countries don’t always have the strict governance codes that apply in much of the West, which require a board to put any valid offer to the company’s shareholders, especially minority shareholders in family majority-owned firms. This leaves family-owned companies free to dodge offers that could dilute their holdings or to favor deals that offer other bells and whistles that mean little to shareholders. Deals based on something other than price-driven logic leave acquiring companies in an uncertain place, prompting many Asian companies that operate in industries that have not yet consolidated to start looking overseas even though deals should be available—or so it would seem—at home.

Asia’s financial sector offers up several examples. In 2005, SinoPac Holdings, one of Taiwan’s smallest banks, rejected a takeover offer from Taishin Holdings, one of the country’s most profitable banks, because some of the shareholders preferred a merger with International Bank of Taipei (IBT) even though Taishin had offered a higher price. Paul Lo, SinoPac’s founder and president, was believed to have preferred IBT because it had agreed to retain his post and to keep the bank’s brand alive. Two previous merger talks fell apart because SinoPac’s management insisted the prospective buyers maintain their posts and the company brand. Like many Asian countries, including Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore, Taiwan’s government had set a consolidation target to reduce the number of players in the finance industry to a few, stronger banking operations. The failure of Taishin’s merger bid illustrated the obstacles that founders and family shareholders in many Taiwanese financial institutions could create to M&A.38 SinoPac ultimately approved the sale to IBT.

Still many more family-owned or founder-owned operations resist mergers altogether. For Asian companies looking to buy, it’s often easier to look elsewhere.

THE RISKS INHERENT IN M&A ARE MORE PRONOUNCED IN ASIA

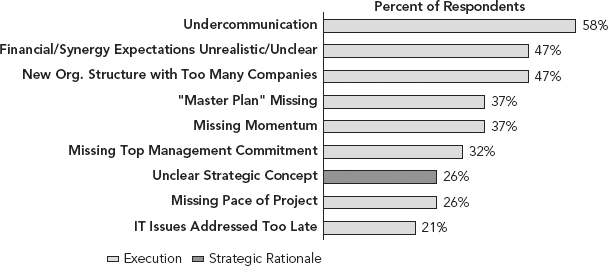

The rise of cross-border M&A looks set to continue its momentum. Yet M&A is a risky business: The failure rate is high. Past A.T. Kearney studies indicate that only 29 percent of companies worldwide see an increase in aggregate profitability, and 57 percent see a decline. That figure drops lower in Asia. Our study showed that just 24 percent of Southeast Asian mergers delivered the expected benefits.

The risk level steepens when companies venture beyond their own backyard. Cross-border synergies are hard to pull off. Culture clashes, poor communication, and lack of local market know-how derail many newly merged cross-border ventures. These risks, which apply to the most seasoned global giant, may be more acute in Asia. The companies fueling Asia’s M&A boom are relatively young and immature and lack experience in M&A. These companies may be doing deals for multiple reasons, which can cause executives to lose focus when they consider potential acquisition targets (see Figure 3.8).

FIGURE 3.8 Problems Identified in Post-Merger Integration

Source: Global Merger Integration Survey; A.T. Kearney analysis.

The thirst for M&A by Asia’s government-linked companies carries its own set of risks. Political leaders worldwide are sensitive about the sale of critical resource or logistics assets to companies owned by foreign governments, particularly where China’s concerned. In 2009, the British-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto walked away from a $19.5 billion offer from Chinalco, which would have doubled the Chinese state-owned company’s stake to 18.5 percent, after the deal became a political issue. Several Australian politicians proclaimed the deal would effectively give the Chinese government control of national resources. “Chinalco is an arm of the Chinese government, so you’ve got a customer, competitor, and sovereign government embedded in the structure, and we feel troubled by that,” Ross Barker, managing director of the Australian Foundation Investment Company, told the newspaper The Australian.39 Rio Tinto’s shareholders eventually panned the deal.

China is not the only bogeyman. Australia killed a proposed merger between the Australian and Singapore stock exchanges in 2011 after a huge political outcry. In April, Australian Treasurer Wayne Swan forbade the merger, saying it was not in the country’s national interest.40

Another hurdle in Asia’s cross-border M&A race is rising valuations. The post-crisis gold rush for undervalued assets has pushed up prices, particularly within Asia. Many of our clients at A.T. Kearney are focused on buying companies that will help expand their regional reach. Asia is getting pricey, and Asian deals are getting harder to find. Most Asian companies have the same ambitions, and increasingly, not enough deals exist. Many of the companies that are on the block have serious issues. They tend not to have perfect governance structures, for example, and they have poor financial reporting. Those issues, which typically come up during the due diligence process, are surmountable but do tend to slow down deals.

Another risk we see is that executives are sometimes too anxious to do a deal; they’ll grab at any deal rather than the right deal. Investment bankers in Asia, keen to capitalize on the boom, are continually throwing up possible targets to companies that are in buy mode. We advise our clients to focus a little more on how these deals will fit into their overall strategy before they go too far down the road.

The gamut of risks and hurdles doesn’t mean that Asian corporations should walk away from cross-border mergers. Instead, executives need to think about how to do it better.

FIVE KEY POINTS BEHIND ASIA’S CROSS-BORDER BOOM

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following A.T. Kearney documents were used as background material in writing this chapter: “Deal Making—Now Is as Good a Time as Any,” a white paper by Vikram Chakravarty, Karambir Anand, and Rizal Paramarta; “Drivers of Successful M&A Integration,” a PowerPoint presentation for the Mergers and Acquisitions Conference, October 20, 2005.

Notes

1. Ann Graham, “Too Good To Fail,” Strategy + Business (strategy-business.com), February 23, 2010, www.strategy-business.com/article/10106?gko=74e5d.

2. “Tetley Bagged by India’s Tata,” BBC.com, February 27, 2000, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/658724.stm.

3. Shankkar Aiyar, “2000 Tata Tea-Tetley Merger: The Cup That Cheered,” India Today (Indiatoday.in), December 28, 2009, http://indiatoday.intoday.in/site/story/2000-Tata+Tea-Tetley+merger:+The+cup+that+cheered/1/76481.html.

4. Ibid.

5. Robert Clark, “Strait Crossing Sees SingTel Take Telkomsel Stake,” Telecom Asia, December 1, 2001.

6. Loizos Heracleous, “SingTel: Venturing into the Region,” Asian Case Research Journal 9, no. 1 (2005): 37–60.

7. Adeline Paul Raj, “CIMB Aims for Top 3 Spot in Asean by 2015,” The Business Times (Malaysia), April 9, 2011, 1.

8. “CIMB Looking to Acquire Banks in the Region,” The Star/Asia News Network, April 10, 2011, www.asiaone.com/Business/News/Story/A1Story20110410–272739.html.

9. Effie Chew and Patrick Barta, “Malaysia’s CIMB Takes Aim at Southeast Asia,” The Wall Street Journal—Asia, March 31, 2010, 33.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. SingTel press release, February 2003.

13. Alvin Chua, “Singapore Telecommunications,” National Library Board Singapore Infopedia, March 21, 2011, http://infopedia.nl.sg/articles/SIP_1610_2011–03–21.html.

14. Lynn Lee, “Antitrust Case: Temasek Loses Final Appeal,” The Straits Times, May 25, 2010.

15. Dhanya Ann Thoppil, “Infosys Wants U.S. Acquisitions,” Wall Street Journal (WSJ.com), February 24, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703408604576163704059394880.html.

16. Bharghavi Nagaraju, “Infosys Eyes Buys in Europe, Japan, and Healthcare Sector,” Reuters, May 1, 2011, www.reuters.com/article/2011/05/01/us-india-infosys-acquisition-idUSTRE7400OQ20110501.

17. Naazneen Karmali, “Sunil Mittal Seals Zain Deal,” Forbes.com, March 30, 2010, www.forbes.com/2010/03/30/bharti-india-telecom-mittal-africa-zain.html.

18. Devidutta Tripathy and Eman Goma, “Bharti Closes $9 Billion Zain Africa Deal,” Reuters, June 8, 2010, www.reuters.com/article/2010/06/08/us-zain-bharti-idUSTRE6570VJ20100608.

19. Ibid.

20. Devidutta Tripath and Sumeet Chatterjee, “Why Is Bharti Chasing Zain’s Africa Assets?” Reuters.com, February 16, 2010, http://in.reuters.com/article/2010/02/16/idINIndia-46194820100216.

21. Peter S. Goodman, “IBM Deal Puts Lenovo on Global Stage: Buyout of the U.S. Company’s PC Divisions Highlights China’s Emergence,” The Washington Post, December 8, 2004.

22. Ibid.

23. Sharon Silke Carty, “Tata Motors to Buy Jaguar, Land Rover for $2.3B,” USA Today, March 26, 2008, www.usatoday.com/money/autos/2008–03–25-ford-sells-jaguar-land-rover-tata_N.htm.

24. Steven Rothwell and Vipin V. Nair, “Tata Motors Plans to Build Jaguar, Land Rover Models in China,” Bloomberg, May 28, 2010.

25. Anirban Chowdhury and Nikhil Gulati, “Tata Motors Profit Zooms as Jaguar, Land Rover Sales Rise,” Dow Jones Newswires, February 11, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20110211–705738.html.

26. “Kirin Eyeing Synergy Among Group Firms in Asia-Oceana,” Nikkei report, August 19, 2010.

27. Michiyo Nakamoto, “Kirin Buys F&N Stake from Temasek,” FT.com, July 26, 2010, www.ft.com/cms/s/0/8f84a796–98bb-11df-a0b7–00144feab49a.html#axzz1Lui1VUaK.

28. Dr. Krishna Kumar and Dr. Kishore Kumar Morya, “Tata-Corus: Spearheading India’s Global Drive to Growth,” 2008, www.london.edu/assets/documents/facultyandresearch/Tata_Corus_Spearheading_Indias_Global_Drive_to_Growth.pdf.

29. Matt Chambers, “China Heads Local Mining Merger and Acquisition Deals,” The Australian, February 16, 2010, www.theaustralian.com.au/business/china-heads-local-mining-merger-and-acquisition-deals/story-e6frg8zx-1225830682572.

30. Rita Nazareth, Christopher Donville, and Elisabeth Berhmann, “China’s Need to Acquire Africa Means Bid for Equinox Increases 18 Percent: Real M&A,” Bloomberg, April 5, 2011, www.bloomberg.com/news/2011–04–05/china-need-to-acquire-africa-means-bid-for-equinox-increases-18-real-m-a.html.

31. Lwazi Bam, director of corporate finance at Deloitte, “Africa Poised for Growth,” April 14, 2011, Deloitte SA blog, http://deloittesa.wordpress.com/2011/04/14/africa-poised-for-growth/.

32. “Tata Taps Equity Markets to Repay Jaguar Debt,” Euroweek 1126, October 16, 2009.

33. Jamil Anderlini, “China to Deploy Forex Reserves,” Financial Times (FT.com), July 21, 2009.

34. Chris V. Nicholson, “Chinese Oil Company Gets $30 Billion Loan for Acquisitions,” New York Times, September 9, 2009, www.nytimes.com/2009/09/10/business/global/10oil.html.

35. Daisuke Wakabayashi, “NTT to Buy African Firm,” Wall Street Journal Asia, July 16, 2010, B6.

36. Kana Inagaki and Juro Osawa, “Takeda, Toshiba Make $16 Billion M&A Push,” Wall Street Journal Asia, May 20, 2011, 1.

37. Chris V. Nicholson, “Thai Union to Buy MWB in $884 Million Deal,” New York Times (NYT.com), July 28, 2010, http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/07/28/thai-union-to-buy-mwb-in-884-million-deal/.

38. Kathrin Hille, “Sinopac Rebuffs Taishin Bid and Opts for Merger,” Financial Times, March 29, 2005.

39. Mark Scott, “Controversy Swirls Around Rio Tinto-Chinalco Deal,” Businessweek.com, March 17, 2009.

40. Eric Johnston, “Singapore Finally Walks from ASX Bid,” Sydney Morning Herald (SMH.com), April 8, 2011, www.smh.com.au/business/singapore-finally-walks-from-asx-bid-20110408–1d6o4.html.