CHAPTER SIX

Due Diligence

Doing a proper due diligence before an acquisition is critical in helping buyers clarify strategy and synergy expectations and uncover hidden issues. Classic due diligence focuses on the company’s financial and commercial aspects. Increasingly, operations due diligence is used as a complement to classic due diligence. Operations due diligence (ODD) evaluates the entirety of the target’s operations to identify potential improvement opportunities that can drive the target to full operational potential and uncovers hidden land mines that may constrain or even disrupt the growth of the target.

Sad stories of gigantic merger failures have become prime time media fodder over the past few years. The painful sagas of AOL Time Warner, Corus, and Vodafone have become textbook cautionary tales. Veterans of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) trade excruciating war stories among themselves about a multitude of smaller, less notorious debacles.

Historically, half of all M&A activities have fallen short in creating lasting shareholder value. A 10-year A.T. Kearney study on the stock performance of companies following a merger reveals that nearly 50 percent of the biggest mergers and acquisitions failed to produce total shareholder returns greater than those of their industry peers in the first two years after the deal closed. Only 30 percent outperformed their industry peers (by 15 percent or more) and had earned a penny more in profitability. Five years after the merger, 70 percent of the survivors remained chronic underperformers in their industries.

What went wrong with all these deals? In attempting to answer that question, analysts have scrutinized and interpreted vast amounts of information. They concluded that M&A disasters can be attributed to poor synergy, bad timing, incompatible cultures, off-strategy decision making, hubris, and greed. One universal lesson is clear: Making a deal work is one of the hardest tasks in business.

As M&A become increasingly complex, the activities of due diligence become more important. From the outset, the buying company needs to understand what it’s getting and what it’s getting into. Between recognizing the potential value of a merger or acquisition and achieving a new and fully integrated enterprise is a dangerous middle ground where, without the proper preparation, anything that can go wrong will. The danger is not that companies fail to do due diligence but that they will do it poorly. The good news is that a handful of due diligence best practices can reduce the risk and give the deal a fighting chance.

A proper due diligence exercise can help buyers clarify strategy and synergy expectations at an early stage. An important part of our due diligence work is a 100-day plan, which helps companies think before the deal is done about issues that will matter later on, issues such as breaking down cultural barriers, motivating employees, and moving quickly to integrate the acquired company.

RISK IS ON THE RISE

The M&A deals that companies tend to strike today are far riskier than those of the 1990s. We can trace the increased risk to at least three converging trends. First, companies in maturing industries are rebalancing their portfolios and selling off pieces of the business. An acquiring company has to untangle the target’s often-entrenched business processes from its parent company and integrate into its own organization cultures those that are often deeply rooted. Second, cross-border transactions, increasingly common because of the global reach of today’s industries, are intrinsically riskier than those within a single country. Third, expectations have changed: In the 1990s, a merger or acquisition was expected to deliver cost reductions, but M&A are often a core growth strategy. Achieving projected growth targets is far less certain than achieving projected cost savings and more difficult to measure.

Despite the waning number of successful M&A, history reminds us that consolidation is inevitable. However, new accounting rules mean the stakeholders will be playing the game differently. Acquirers will need to perform better upstream planning and detail the reasons behind an acquisition. Boards of directors and investors will demand a more thorough assessment of potential targets, and acquisitions will take place only when there are identifiable, quantifiable operational synergies. If a purchasing company fails to gain a full perspective of the potential partner prior to the acquisition, realizing value from the deal will be nearly impossible. CEOs will be motivated to prepare for the acquisition well beforehand even as it is still at the idea stage. The ideal acquisition will begin by pinpointing a target that the acquirer can “fuse” with, and end with a well-handled integration, skillful management of initiatives, projects, and risks, and minimum loss of customers and talent.

FOLLOW THE LEADERS, LEARN FROM THE FAILURES

In recent years, a few companies have demonstrated exceptional proficiency in assessing their target acquisitions, evaluating them first as stand-alone organizations and then factoring in the value of any potential synergies. Cisco Systems’ CEO John Chambers avoided large-scale employee turnover and leveraged the acquired firms’ products and technologies throughout his acquisition spree of more than 70 companies. Kellogg’s rewarded its shareholders with a 25 percent return a year after it acquired Keebler Foods. General Electric (GE) bought 534 companies in six years without much fuss. Granted, few of these deals were complex mergers of equals, but the acquirers achieved speed and success because of thorough integration of the target into the buyer company’s business processes and well-defined, time-tested integration practices.

Such stories of skillfully managed mergers rarely make a splash in the media, but their impact on long-term shareholder value is obvious.

Unfortunately, most companies are not as adept. They target and buy without understanding what they have bought. They underestimate integration and deal costs, overestimate savings, and imagine synergies that do not exist. Shortly after the merger of AOL and Time Warner, the new CEO, Richard Parsons, said the synergies ascribed to the deal were oversold. “Time has not even been able to get its AOL email to work properly,” he told Newsweek. Two years after Vivendi’s acquisition of Seagram’s entertainment business, there was scant evidence of synergies between the company’s U.S. and European assets. The merger between British Steel and Hoogovens, in 1999, which formed Corus, was supposed to create one of the largest steel companies in the world with a $6 billion market capitalization. The business was worth a mere $250 million; Tata Steel swooped in and bought the distressed company.

What went wrong for these companies? They did a poor job of planning. They failed to identify the risks in integrating two organizations with different management and operational processes, and the results were predictable: management strife, political interference, employee rebellion, and disastrous financial results. If they had done the right kind of due diligence, these problems could have been identified and dealt with early on.

BRIDGING THE DUE DILIGENCE GAP

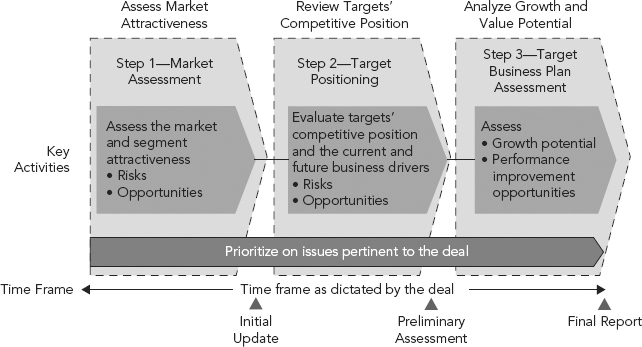

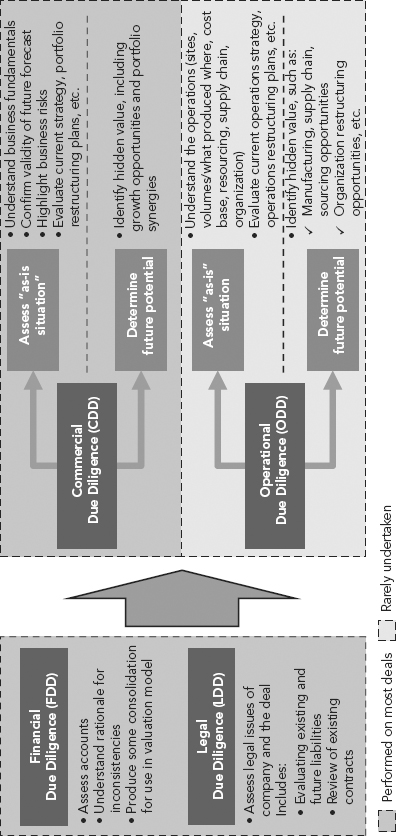

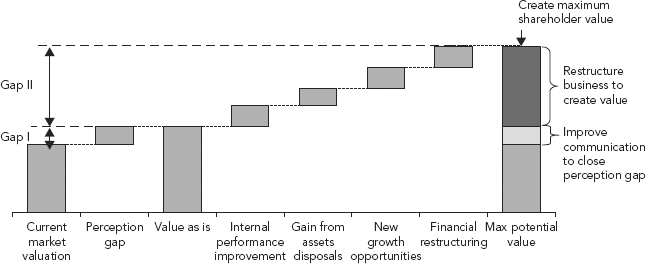

Due diligence is a key activity in M&A because it is the point at which the potential for value creation and purchase price are determined. Most acquirers perform commercial due diligence (CDD) or strategic due diligence—a review of financial and commercial data—to assess the state and potential of a target prior to the transaction. Increasingly, companies are going a step further and performing an ODD as part of their standard merger assessment in an effort to capture value sooner and dispel any hint of failure (see Figure 6.1).

FIGURE 6.1 An Integrated Approach to Due Diligence Includes Financial, Legal, Commercial, and Operations Due Diligence

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

Private equity firms were the first to put ODD into practice, and they set the bar higher by forcing today’s deals to show value quickly. Historically, private equity funds have been successful in identifying companies with untapped growth potential. By using a mix of financial engineering and some limited operational restructuring, they have been able to increase the value of their targets and generate substantial returns for their investors. However, more competition for good deals has led to higher-priced assets and a simultaneous increase in the required returns hurdle. At the same time, financial engineering has become less of a differentiating factor for value creation. Factor in the global financial crisis, the higher price of debt, and increased level of covenants, and private equity firms have been forced to seek value elsewhere. They settled on ODD as a strategy for discovering short-term value creation potential such as tangible top-line and bottom-line improvements immediately after closing a deal. This strategy has helped mitigate many of the risks that typically undermine M&A.

We firmly believe that operations are an underexploited route to value creation. Among the growing number of successful deals closed by traditional firms following in these first movers’ footsteps is the $47 billion merger of Procter & Gamble (P&G) and Gillette in 2005. The prompt integration of operational processes, particularly in sales and procurement, led to a speedier integration, smoother transition and faster realization of synergies. At P&G and Gillette, and similar companies, ODD and attentive merger planning are quickly boosting the value of the merged company.

Unlocking the value in operations is an art and a science. Doing it well requires the following:

- Understanding the true full operational potential.

- Identifying and quantifying improvement opportunities that can be implemented quickly.

- Determining possible land mines that may constrain or, even worse, disrupt the growth of target companies.

- Developing a resource plan and implementing the initiatives with the cooperation of the operations team (a critical but often neglected element of the due diligence process).

DUE DILIGENCE: THE CLASSIC APPROACH

Due diligence is an overall term that typically refers to three broad areas: CDD or strategic due diligence, which seeks to determine if a market exists, analyze whether it’s attractive, and map out the competitive landscape; legal due diligence (LDD), which analyzes contracts and other documents; and financial due diligence (FDD), which looks for inconsistencies in the accounts. We refer to this three-in-one approach as classic due diligence. Though it has served acquirers well in the past when increases in earnings multiples or the ability to increase financial leverage might have been sufficient, the approach fails in evaluating a firm’s operations and the ability to execute a business plan.

The FDD and LDD work streams focus on building a historical fact base, particularly in relation to regulatory and compliance issues. They typically provide caveat emptor advice, often with many facts but little prioritization of risks, and are backward-looking by nature. These work streams provide a context within which a target’s future performance can be evaluated.

By contrast, the CDD work stream typically provides a forward-looking evaluation of the target’s prospects, focusing on the business and industry fundamentals and evaluating the firm’s strategy and competitive position. CDD includes analysis of the markets the company is currently in, potential new markets it could address through new products and services, and the degree to which it is suitably positioned to target that growth. It should assess the risks and challenges, such as technology changes, that might impact how the market is likely to evolve, or assess regulatory risk. It could, for example, include an assessment of the likelihood of a mining company obtaining a new license to expand its operations. Often, however, say CDD critics, it places too much emphasis on best-case scenarios.

Investors use CDD analyses and insights to refine their bid-valuation model but this often does not adequately consider the firm’s operations. Consequently, performance gaps that could provide short-term value-creation opportunities, when overlooked, lead to two significant challenges for acquiring companies: first, the inability to establish the firm’s true full potential and, second, the inability to determine the real business risks. Failure to assess properly a target’s internal inefficiencies is often the reason acquisitions that previously appeared attractive ultimately disappoint.

OPERATIONS DUE DILIGENCE

Operations due diligence (ODD) complements the scope of a CDD and, through its focus on the target’s operational capabilities, aims to bridge the classic due diligence gap. Operations due diligence is executed in an integrated manner alongside CDD, with the two work streams collaborating to incorporate each other’s findings.

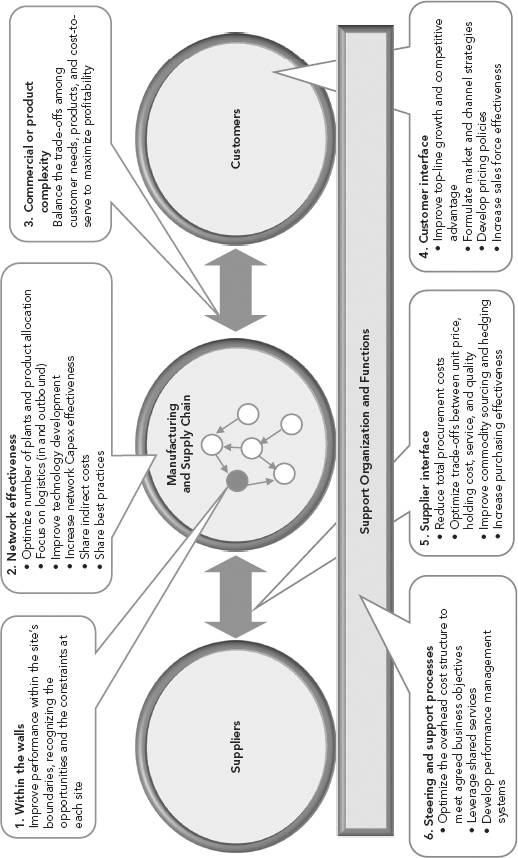

Commercial due diligence (see Figure 6.2) focuses on the target’s strategy, competitive position, and industry attractiveness, and assesses growth opportunities and portfolio synergies. Operations due diligence (see Figure 6.3) focuses on providing a deeper understanding of the target’s business operations, including manufacturing, supply chain, cost base, organizational structure, resourcing, and operations planning, and provides a balanced view of an investment’s opportunities and potential pitfalls, nailing down the full potential value. This kind of analysis helps buyers understand what kind of value they can squeeze out of the company from within. Not least, ODD provides the wherewithal for a reality-based conversation with the acquirer about the target business.

FIGURE 6.3 Operations Due Diligence Evaluates the Target’s Entire Operations

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

Specifically, ODD provides for the following:

- Evaluates target’s entire operations, including sites, volume, production content and location, costs, resources, and supply chain efficiency, among others.

- Benchmarks performance and identifies where, how, and when to make improvements, and how to do so as easily as possible.

- Considers the potential capital expenditures and working capital levels required to realize the target’s full potential.

- Accounts for the risks and constraints that current operations place upon the target’s ability to achieve its business plan.

Acquiring companies obtain significant advantages from this deeper understanding of the target’s operations, a chief one of which is the ability to identify opportunities for unlocking incremental value.

For example, as part of the due diligence exercise in a recent project, we assessed the overall operations for a glass manufacturing plant. The objective was to identify opportunities and risk that could potentially impact the overall operations and, in turn, the revenues. Our assessment focused on operational parameters and capital expenditure drivers.

We were able to pinpoint and articulate the potential improvements across key processes of glass manufacturing that would boost the production volumes without compromising on quality. Though the operating teams typically can improve these parameters on a regular basis, our assessment used a combination of three key sources of data to test and stretch the operating parameters further. Our recommendations included the following:

- Tweaking the production scheduling, especially during color and job changes, to minimize losses by up to 3.5 percent.

- Optimizing the recipe to augment output and reduce raw materials cost and energy usage. Our plan cut energy consumption by up to 5 percent and increased output by up to 5 percent.

- Improving furnace operations, operating smarter to increase daily output without causing unreasonable wear.

- Improving machine operation by making adjustments to increase speed without risking excessive defects.

These changes, along with others, improved the overall output of the plant and reduced the costs across several operating areas.

In terms of capital expenditure, we identified an ability to “sweat the existing assets,” which meant some of the upgrading plans could be delayed by almost two years.

The result was improved cash flow and, in turn, value. We helped prioritize capital expenditures and developed a business case for the acquisitions, which gave the investor—in this case, a private equity fund—more confidence in the source of earning improvements and allowed it to bid more realistically.

In another example, we were involved in an automotive industry project to conduct an ODD on a power train manufacturing company in Asia. The business was at a crossroads: It was expected to grow, but due to its move from a domestic market to an export market, its complexity was expected to increase and constrain its ability to fulfill overall demand.

Based on the due diligence, we identified three key areas of potential improvement:

We used a comprehensive approach to review the current state of the company across the three areas mentioned above. The new owners of the company requested us to help implement the initiatives we identified during the due diligence stage. The benefits delivered across the three areas are listed below:

Because ODD provides an improvement agenda backed by detailed analyses, it can be used to facilitate negotiations with the target’s owners and management. The results provide input into the 100-day plan, allowing the acquiring company to link specific short-term improvement initiatives directly to management incentives.

The Approach: Six Areas

The ODD approach focuses on six areas, evaluating a target’s internal capabilities and the measure of its effectiveness in interfacing with its external environment (see Figure 6.4).

This balanced assessment, taking into account the target’s costs, operations, revenues, and margins, includes an evaluation of support functions, such as finance, human resources, and IT. This ensures that outsourcing and shared services concepts are fully leveraged.

The first operational issue that must be examined lies within the walls of the target company itself: how many production facilities, for example, and their operations efficiency, their employee numbers, the cost per unit, and the bottlenecks and the capital expenditure needed to get rid of them. A lot of this can be accomplished by benchmarking the plants against the industry.

The second operations issue is network effectiveness: If a company has five plants making products for five markets, we need to look at what can be done to improve efficiency by focusing certain plants on certain markets or moving capacity from one to another and potentially shutting down those that aren’t needed.

We need to look at the product offering and the customer interface: Is the company offering what the customer wants, or is the product offering too complex? We need to achieve the right balance between product and demand, and link that to the plant network. At the same time, there may be ways to improve pricing, sales force effectiveness, and channel strategies.

Procurement is another big area of potential savings, and this is typically where we find quick, easy-to-tap value. A.T. Kearney has access to information on a range of businesses and can easily assess whether materials prices are too high or priced appropriately.

Capital investments, meanwhile, is one of the most important areas we focus on during operational due diligence. Most companies have a capital expenditure plan designed to push their growth plans. Often, after making a site visit and benchmarking the plant performance, we find that much can be done to boost efficiency at no further cost. Sometimes, the opposite is true, and capital expenditure plans fall short of growth goals. In that case, an acquirer may wind up having to inject more capital later.

The areas of focus for an ODD project are established by assessing the market and the target’s unique situation. The objectives, for example, could be conducting a diagnostic to understand current operations, benchmarking current operations, quantifying opportunities for value creation, or a combination of any of these.

Our approach is based on the following:

- Site visits. Crucial information about a target’s operational capabilities and a firsthand view of asset health are a couple of the advantages of making a site visit, and they help evaluate the site team’s capability.

- Processes and capabilities assessment. Given the ODD time frame, the focus is limited to high-priority, mission-critical processes. The processes for each industry or function are assessed using a comprehensive set of questions and process maps.

- Benchmark operating parameters. The best quantification of operations value comes from benchmarking operating parameters; external consultants and key technical experts in the industry provide a solid database of information that supports the benchmarking.

These three elements feed into the “operations upside model,” which is similar to the commercial upside model, and provide information on the following: the operating expenditures plan, the capital expenditures plan, the potential upside from release of additional capacity, the risks with asset integrity, and the risks and bottlenecks with the current operations setup.

As discussed above, ODD can help potential acquirers unlock a target’s full potential value and identify ways to capture this value. In an ODD exercise we conducted on a flexible packaging company in Europe, for example, plant optimization offered the best opportunities for potential value. The company had a fragmented network of more than two dozen small factories, most of which were operating at less than full capacity. We recommended it consolidate its plants and close six, and focus certain plants on certain products, which would allow the company to streamline the technology at each of the remaining plants. The company’s supplier base was fragmented in certain categories, and it could achieve considerable savings by consolidating that base. Overall, our team estimated the packaging company could improve earnings before interest and tax by 20.6 million euros and improve cash flow by 22 million euros if it followed the most conservative set of recommendations from our due diligence study.

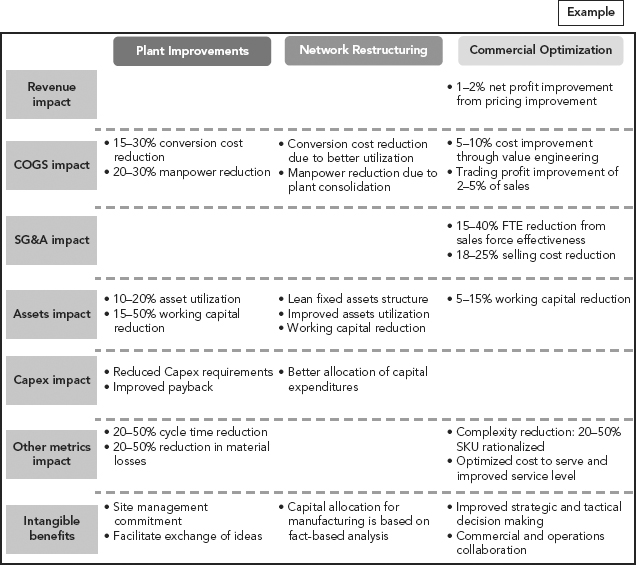

Several value levers are standard in almost any merger (see Figure 6.5). We’ve done a wide body of work with manufacturing operations, for example, and have found that plants can typically reduce manpower by around 20 to 30 percent, improve asset utilization by 10 to 20 percent, and reduce working capital by 15 to 20 percent. Most factories we look at can also reduce material losses by 20 to 50 percent. We will find ways to wring a 1 to 2 percent improvement in net profit from pricing improvement alone, and we are typically able to reduce costs by 5 to 10 percent through value engineering.

FIGURE 6.5 Implementing Operational Improvements Can Create Substantial Value

Source: A.T. Kearney analysis.

A solid ODD map can be used to begin a more wide-ranging conversation with the target company’s owners. Finally—and perhaps most importantly—ODD helps investors identify the potential risks of an investment before making a financial commitment.

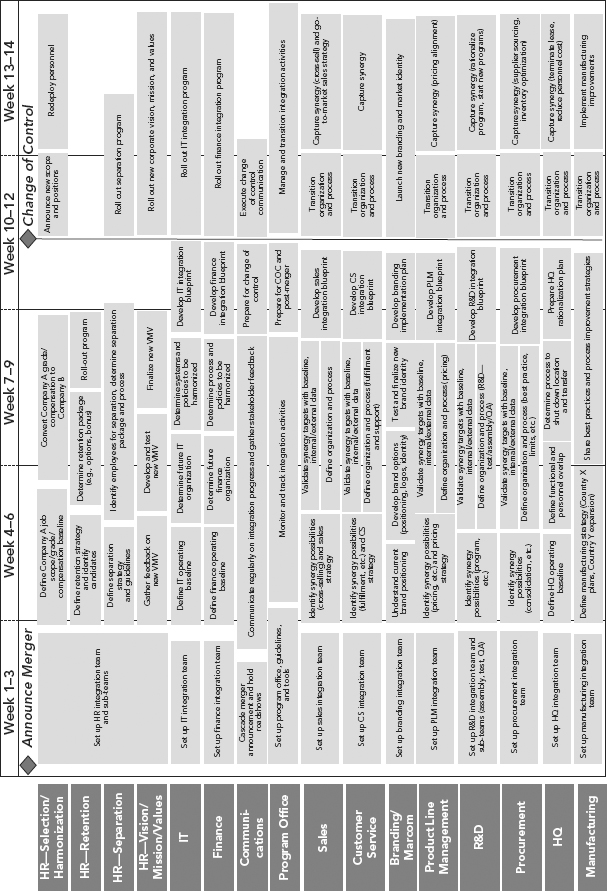

THE 100-DAY PLAN: A ROAD MAP TO SUCCESS

Operational due diligence establishes an opportunity to create the road map that unlocks value during the immediate post-deal phase: the 100-day plan.

About 80 percent of the value of synergies between two companies is typically captured in the first 12 months of a merger. You can’t wade in; you have to get off to a flying start from the first moment a merger is legally approved. That’s easier said than done. Cultural clashes, low staff morale, and confusion can mire any integration exercise.

Operational due diligence allows executives to define the value levers, assess the ease of implementation, and analyze the capabilities of the staff. That puts them in a position to prioritize what they want to achieve and lay this out in a 100-day plan. This plan is a precise set of activities to be undertaken during the first 100 days and allows executives to gun for the value creation opportunities identified during the ODD. Figure 6.6 provides an overview of what goes into a detailed 100-day plan.

The plan maps out value creation initiatives—such as rationalizing factories, cross-selling products or consolidating suppliers from the two merged entities, and negotiating better deals—and includes the key enablers that will support value creation, including human resources, people training, compensation, IT, financial reporting, process changes, and communication with staff and customers.

Putting a 100-day plan down on paper ensures leadership teams from the two merged entities get organized and focused on the goals at hand. It brings people together. Under a typical 100-day plan, executives create joint teams and assign the responsibilities and goals those teams must deliver on. That tends to galvanize staff and have everyone immediately working together, which in turn gives purpose, boosts morale, helps people get comfortable with each other, and dissipates some of the cultural clashes than can slow a merger.

A 100-day plan reduces uncertainty. Talent and customer retention are key issues during a merger. You don’t want your best people to walk out the door because they’re uncertain about their future or your best customers to jump ship because they’re worried about continuity.

JUMP-STARTING THE CLEAN ROOM

The move to capture value can start before a buyer takes legal control of the acquired company. The earlier the work begins, the better. Remember, most synergies are captured within the first year: Every week counts.

The challenge is that a merger is not legally complete until the regulators give approval. That can take weeks or months after a deal is signed. Many restrictions exist on what kind of information two companies can share and what must remain confidential until the legal box is ticked.

Here’s where having an independent third party involved can help. Consultants can operate a “clean room” that they can use to analyze confidential data from both companies, work out the synergies, and craft a plan for the first 100 days of the legal, post-merger stage. Companies that undertake an ODD and use a clean room to jump-start their 100-day plan can extract value from a merger almost immediately.

This is not a new idea: When companies are being sold, they typically create a “data room” and release information to the bidder in a systematic way. We take this a few steps further. If the merger is likely to happen, we advise clients to set up a clean room where both parties share the information required to make the value-creation opportunities more specific and tangible.

For example, many synergies can be captured on the cost side in a merger. When two companies come together, they can buy double the raw material, for example, which boosts their negotiating power. Consultants running a clean room can pinpoint cost reductions across the buying cycle, get data from both companies, and map out a strategy to deal with suppliers. On day one, an executive involved in the closing can sit down and start negotiating new contracts with those suppliers. Companies that don’t run a clean room can spend six or seven months plodding through the process.

It’s all about getting it right early on.

DUE DILIGENCE FAQ

When we first approach companies with our operations due diligence strategy, we typically seek to answer several key questions at the outset:

Q: Can operations due diligence take place without access to the target?

A: Unrestricted access to the target company is desirable through the due diligence process but often is limited due to confidentiality and commercial concerns. When such restrictions exist, ODD can be performed by internal industry experts and through the use of intellectual property and global benchmarks.

Q: Can this be done internally by our company?

A: Some form of pre-deal assessment of the target’s operations should always be undertaken. When an investor has considerable operational expertise in the target’s market, an internal review may be sufficient. However, when industry familiarity is lacking or the operations are sufficiently complex, a formal ODD process is preferred.

Q: How long does the process take?

A: Operations due diligence is run simultaneously with the CDD work stream and typically spans three to four weeks. The scope of the pre-deal ODD is determined by considering the industry and the target’s situation, and initial hypotheses and focus areas are determined in consultation with the client. A two-phase process highlights key “red flags” during the pre-deal evaluation and provides value-creation assistance during the investment-holding period.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The following A.T. Kearney white papers and articles were used as background material in writing this chapter: “Bridging the Due Diligence Gap,” by Vikram Chakravarty, Badri Veeraghanta, Francesco Cigala, and Adam Qaiser, 2011; “Due Diligence: Think Operational,” by Jürgen Rothenbücher and Sandra Niewiem,” 2008; “Mergers and Acquisitions: Reducing M&A Risk through Improved Due Diligence,” Strategy & Leadership 32, no. 2 (2004), by Jeffery S. Perry and Thomas J. Herd, both A.T. Kearney alumni; “Breakthrough Value Creation in M&A,” by Vikram Chakravarty and Navin Nathani, Financier Worldwide (e-book), 2009.