CHAPTER ONE

Asia Rewrites the M&A Rules

Consolidation follows a fairly predictable pattern in developed economies in the West: Big fish eat little fish in the domestic market, and a small handful gains dominance of the pond. These dominant players start looking for targets abroad after they’ve built might and muscle at home. Domestic consolidation precedes global mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

Nobody, however, told that to India’s Tata Tea.

In February 2000, Tata bought Tetley Tea, a 160-year-old British company and one of the world’s best-known tea brands, for $431 million. Tata Tea, a relatively young company, was one of many players in India’s large, diverse tea sector that had yet to go through consolidation. That didn’t stop Tata from heading overseas or homing in on much bigger prey. Tetley Tea was three times the size of Tata.

Asian companies are rewriting the rules on M&A. Small Asian players are buying large Western brands. Asian companies that compete in crowded, fragmented domestic markets are snapping up competitors over the border instead of in their own backyard. Waves of consolidation are sweeping through Asia, but it won’t play out in a textbook fashion. The reasons Asian companies undertake M&A are different, the way they approach M&A is different, and the way Asia’s consolidation story will play out will be different, too.

DEAL ACTIVITY IS ON THE RISE IN AN ASCENDANT ASIA

The plot of this particular story is starting to thicken. Asian companies emerged from the 2008 global financial crisis and entered the 2011 slowdown in a stronger financial position than many of their Western peers; they’re relatively cash rich and hungry for acquisitions. Strong Asian currencies are giving these companies plenty of firepower as is the legion of investment banks competing to grow their loan books in Asia, one of the few growth markets around. Numerous sectors in the region’s emerging markets, meanwhile, are ripe for consolidation. Western companies, anxious to tap one of the world’s strongest bastions of growth, want to get skin in the game. These multiple drivers are all playing out in the numbers.

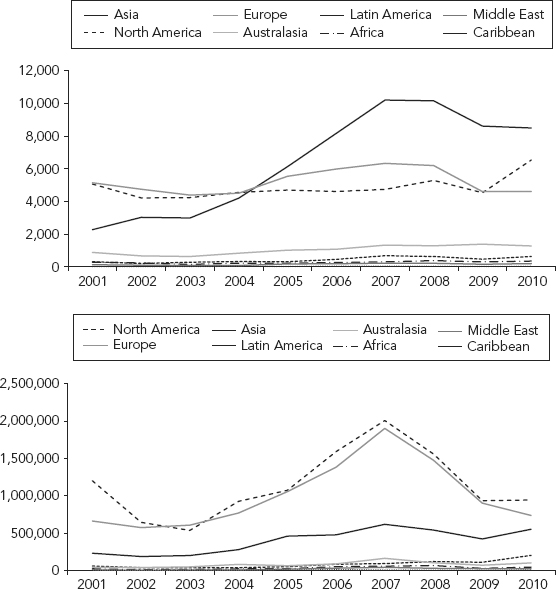

Asia Pacific was the most active deal region in 2010, reporting over 8,300 mergers or acquisitions that involved an Asian company as the buyer or seller, according to Dealogic (see Figure 1.1). That figure outstrips Europe and North America by volume. North America and Europe account for more global M&A deals by value, but Asia is trending upward at a time when those two markets are declining. Asia nearly tripled the value of deals between 2001 and 2010, from $230 billion to $552 billion, and more importantly, it has increased its share of the world’s M&A pie. Back in 2001, Asia’s share of global M&A was one-fifth of North America’s and one-third of Europe’s share. By 2010, the picture was markedly different: Asia’s share was about half of North America’s share and slightly more than half of Europe’s share, according to Dealogic.

FIGURE 1.1 Global M&A Deals by Volume (top graph) and Value (bottom graph, in USD millions)

Source: Dealogic.

China and India are fueling this growth, with a growing appetite for acquisitions. China chalked up $112 billion worth of in-country deals in 2010, up 120 percent from 2007. India’s M&A streak was equally hot. The value of deals done in India grew by 198 percent to $45 billion. The number of in-country deals doubled in both markets during that same period.

Pull these numbers apart, and the story gets more interesting. Asian companies are driving most of the region’s M&A boom, inside and outside Asia. They’re snapping up domestic competitors, regional companies, and global brand names in Western markets faster than ever before. Asian companies are pouring into Europe and North America.

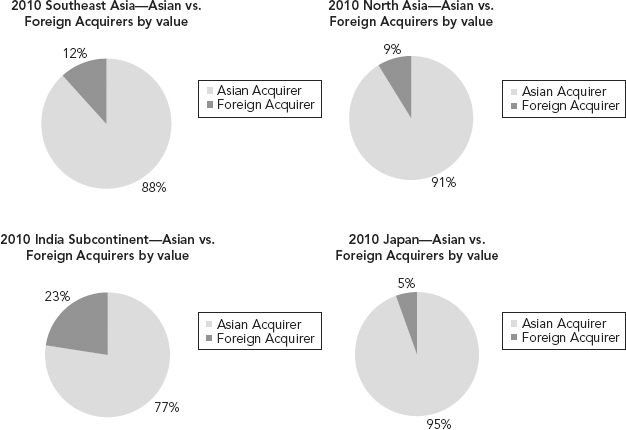

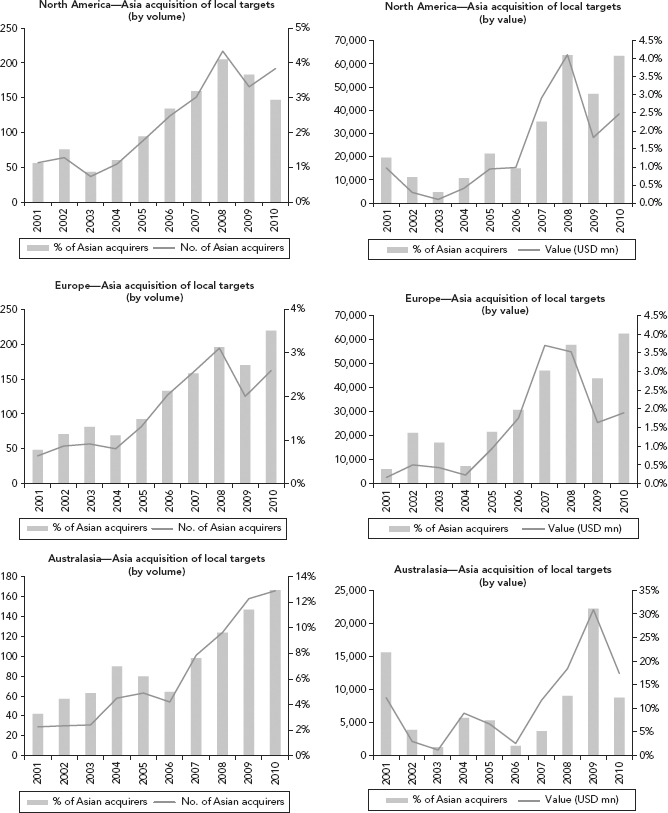

Asian acquirers accounted for 91 percent of deals done in North Asia in 2010, 88 percent of deals in Southeast Asia, and 77 percent in the Indian subcontinent (see Figure 1.2). The number of Asian companies making acquisitions in North America more than trebled between 2001 and 2010 and quadrupled in Europe in the same period (see Figure 1.3). They’re having a huge impact, too. India’s Tata, which also owns Jaguar Land Rover and Corus Steel, employs 40,000 workers and is now the United Kingdom’s largest industrial manufacturer, according to The Economist. (For more on Tata, see Tata Tea Leads Global Acquisition Charge, in Chapter 3.)

FIGURE 1.2 Asian versus Foreign Acquirers in 2010, by Value: Southeast Asia, North Asia, Indian Subcontinent, and Japan

Source: Dealogic.

FIGURE 1.3 Asian Acquisitions of Foreign Targets (by volume and value): North America, Europe, and Australasia

Source: Dealogic.

Mergers and acquisitions are going to dominate Asia’s business landscape over the next decade. Every company interested in Asia needs to understand how this will play out in their particular industry. Asian companies, meanwhile, need to invest more time developing a solid game plan. Deal activity may be picking up steam, but Asian companies are relative novices when it comes to M&A. Many Asian companies don’t plan for it, and few executives have much merger expertise. We believe Asian companies that understand why M&A in Asia is different—and figure out how to capitalize on that—will emerge as champions of their industries. In Chapters 5, 6, and 7, we’ve created an M&A primer for Asian executives on how to plan and execute a successful integration.

NATURAL PROGRESSION IN M&A, THE ASIAN WAY

Consolidation is a natural consequence of free market forces. Companies acquire local competitors when markets get crowded, growth slows, and margins sag. In Asia, certain barriers remain that impede and redirect the natural forces and currents of a free market flow. Government-linked companies dominate certain sectors and often resist consolidation; some industries in certain countries, meanwhile, remain protected, like Malaysia’s oil, China’s steel, and India’s retailing industry. We focus on this trend in Chapter 4, and talk about how Asia’s public sector could revitalize itself through M&A. Family-run companies also have a strong presence across Asia, and they don’t always make decisions based on financial reasons alone. Many have rejected good acquisition offers to hang on to control.

More cross-border M&A activity is occurring in developing Asia than analysts would expect, given the stage of development of the region’s economies. The classic call would be long on local consolidation and short on cross-border activity in the region’s more fragmented industries. These made-in-Asia barriers, however, are driving acquisitive companies over the border or overseas earlier than you’d expect in a textbook consolidation wave.

It’s not just push—there’s plenty of pull. Asian companies are moving fast to acquire regional or global competitors to gain access to new markets, new technologies, new brands, more resources, and better research and development capability. These companies want to use their capital to catapult up the value chain, in double time. We examine this trend in detail in Chapter 3.

Asia is also home to a diverse and fragmented set of consumer markets, which gives another twist to the consolidation story. Income levels are all over the map, with a wide range of affordability. A wide variety of ethnicities, languages, and cultures impacts consumer tastes and preferences. What customers in one country might need and want differs among the provinces, never mind among consumers in the country next door.

This particular scenario will redefine the outcomes of Asia’s merger endgame. In the West, a small handful of large companies dominate a market after various rounds of consolidation. Two or three big players will typically command a 60 to 70 percent share. Free market advocates argue that industries naturally settle into a situation where an optimum number of sizeable players command control, earning economies of scale that allow them to thrive and pass the best prices on to consumers.

Asia’s fragmented markets will give rise to series of sub-segments at different price points within each market. Coca-Cola, for example, might dominate a national soft drinks market, but local soft drinks that cost less and come in flavors that appeal to local tastes will dominate specific segments. Local companies with strong consumer insight will have the edge in segmented markets like this. Industries, meanwhile, will not be dominated by an “optimum” number of large companies. Consolidation will play out along these segmented lines, giving rise to what we call “local optima,” meaning small clusters of local champions that will dominate different price points or subcategories. We go into depth on this in Chapter 2. Asian companies that can start planning now, while their industry is still in the nascent stage, can make tactical moves that will put them ahead of the curve before the industry matures.

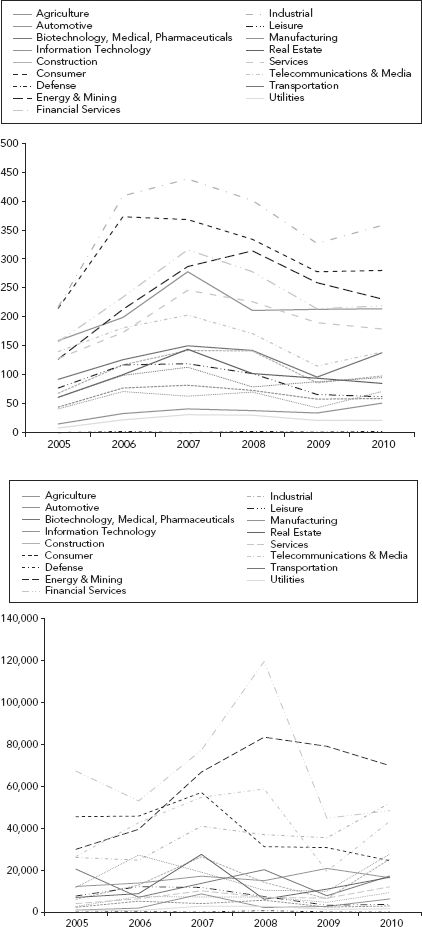

Asia’s industrial and consumer sectors, along with energy and mining, are the hottest deal sectors (see Figure 1.4). Asia’s energy sector chalked up a whopping $70 billion worth of M&A deals in 2010, according to Mergermarket. The industrial and financial services sectors were the second most active by value. The consumer sector was the second most active by volume, a signal that Asia’s developing markets are starting to mature and smaller players will increasingly be subsumed as margins start to fall.

FIGURE 1.4 Asia M&A Deals by Sector, by Volume (top graph) and Value (bottom graph, in USD millions)

Source: Dealogic.

TOMORROW’S WINNERS ARE MOVING FAST, TODAY

All of these factors equate to one conclusion: Now is the time for deal making.

Many Asian industries are in the developing stages, but consolidation is right around the corner. Executives who anticipate what’s ahead are better placed to steer their companies in the right direction. Companies who ignore the road signs risk being swallowed by more forward-thinking peers.

There are risks. The vast majority of M&A fail to deliver the originally anticipated value. That’s typically due to poor planning, poor execution, and cultural clashes between staff from different companies and countries. We provide practical tools on how to troubleshoot these problems before they crop up in our M&A “primer” section, starting in Chapter 5. Cultural clashes can trip up a merger at the starting gate: Asian executives need to understand this critical, but often overlooked, issue before they start snapping up companies in the West. Chapter 8 provides insights, examples, and useful tools to help acquirers navigate this potential minefield.

The ongoing volatility in global markets creates opportunity. Asia weathered the 2008–2009 global financial crisis well, and the IMF and World Bank tipped it as the engine that would power the world out of recession. When consumption from Western markets dropped off, Asian consumers stepped up to the plate and the region’s economies ticked along on the back of strong domestic demand. Asian companies saw opportunity and took it. The level of M&A activity in Asia stayed constant between 2008 and 2010 even as Europe and North America fell off a cliff, as illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Then came a second wave of bad news. In the last half of 2011, the twin specter of a double-dip recession in the U.S. and the European debt crisis roiled global markets. Economists scrambled to revise global forecasts downward. The volume of global M&A deals dropped by about 20 percent in the second half of 2011 compared with the first half. The pace of deal making slowed in Asia, too, but in a less dramatic way: Deal activity in Asia dropped by less than 10 percent.

Our view is that bleak economic scenarios present opportunities to strong companies, who make use of this volatile time to bolster their standing in their respective industries and to orchestrate “game changing” initiatives. We believe strong companies must actively seek out opportunities to consolidate their industries and gain market share, acquire new technologies and know-how, strengthen their competitive advantage, and position themselves to take advantage of an improving economy. M&A is the ideal mode for such opportunities: It’s a buyer’s market and companies acting now are likely to emerge as winners when the upswing comes. Timing is everything.