CHAPTER TWELVE

Investigation

Incident Closure

I think I did pretty well, considering I started out with nothing but a bunch of blank paper.

—Steve Martin

THE EFFORT REQUIRED in the next phases of an investigation is as systematic and thorough as any of those previously discussed. Although the process is fairly linear (see Figure 12.1), the “steps” of the investigative process are not necessarily successive or consecutive; they may overlap and vary depending upon case. Phases themselves allow for specific customization suiting various requirements: legal, lawful, corporate, or otherwise.

FIGURE 12.1 Steps in the Investigation Process

FORENSIC INVESTIGATIVE SMART PRACTICES

STEP 5: INVESTIGATION (CONTINUED)

“in•ves•ti•ga•tion”

1. The action of investigating something or someone; formal or systematic examination or research.

2. A formal inquiry or systematic study.

In some circumstances, a cyber forensic investigation could be defined as simply the action of extracting data to meet a given search criteria; something easily accomplished in an automated manner. This definition could certainly apply if under contractual obligation or court order. The “Sherlock Holmes” aspect of an investigation may not always present itself; the investigation may be strictly limited to the search criteria.

At times, a cyber forensic investigator can become over sensitized to the systematic nature and become dependent and eventually reliant upon forensic tools for data extraction. If not inquisitive, Ronelle would not have noticed, or cared to notice, the time discrepancy observed during the investigation. It is this challenging or questioning that, at times, makes up the investigative nature experienced in cyber forensics. This investigative nature is assured with the advances in technology.

Operating Systems are numerous and change frequently, along with constant upgrades, patches, updates, service packs, and so on. An increase in volume and variety of electronic device types also introduces numerous new operating system types and versions. It is this dynamic nature of the field that fuels the need for much investigation.

Many times it is important for the investigator to step back and explore the “rabbit hole” or irregularity (the 32-bit timestamp discrepancy in Ronelle’s case, for example) to ultimately be able to explain why such a thing exists. Any exercise in expanding or gaining a better understanding of such an important field is worth exploring.

Now armed with a firm understanding of the time discrepancy, Ronelle feels confident in fully understanding the data she extracted. If requested, Ronelle could examine the data collected and perhaps acquire some additional key words or other search criteria. How an investigator proceeds will vary drastically across the forensic landscape.

Ronelle presented the initial findings to management and suggested new keyword searches. In this circumstance, the Legal department made the decision that they had what they needed and stopped the investigation. The reasons for putting an investigation on hold can vary widely. One major determining factor would include the financial aspect; conducting cyber forensic investigations can be an expensive affair.

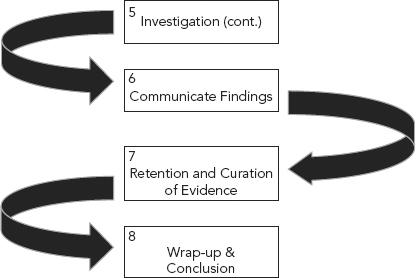

The cyber forensic investigator now needs to communicate the results and findings of the investigation, the deliverable being the investigator’s report. See Figure 12.2.

FIGURE 12.2 Step 6: Communicate Findings

The cyber forensic investigator is responsible for accurately and objectively reporting his or her findings and the results of the analysis of the digital evidence examination. Documentation is an ongoing process throughout the examination/investigation; it is important to accurately record the steps taken throughout the digital evidence examination process.

All documentation should be complete, accurate, and comprehensive. The resulting report should be written for the intended audience.

The purpose of the report is to:

1. Deliver the results of search criteria defined in the request.

2. Document the findings in an impartial and accurate manner and provide responsible authority information, to assist in making a determination whether to take corrective, remedial, or disciplinary action.

3. Organize the information so that anyone can read and understand the report without reference to enclosures or other material.

The cyber forensic investigator typically is barred from publishing, distributing or in any manner communicating, independently, the contents of the report to anyone other than authorized persons.

CHARACTERISTICS OF A GOOD CYBER FORENSIC REPORT

Clarity, completeness, objectivity, and accuracy are characteristics of a good report. The report must be clear enough so that others may understand what the writer means. But more than that, it must be written so clearly that others cannot possibly misunderstand the writer’s meaning.

Clarity results from a report that contains a concise, systematic arrangement of facts and analysis stated in precise, neutral terms. Completeness dictates that all information a prudent manager reasonably would want to consider before reaching a decision should appear in the report.

Objectivity is arguably the most important trait. An investigator uncovering incriminating data cannot allow him/herself to be swayed, thereby affecting the disposition of the report. Simply put, the investigator cannot “take sides.” Lack of objectivity will negatively affect the style and tone of a report. As Sgt. Joe Friday would state, “Just the facts, ma’am.”

Accuracy requires there be no errors in reporting facts or identifying people, places, events, dates, documents, and other tangible matters. A good rule of thumb requires asking whether a person who knows nothing about the case could read the report, fully understand what happened, and feel confident in making a decision based on its contents.1

Style and Tone

Whether the allegations are sustained or refuted, most reports convey bad news to someone.

Proper style and tone makes the news easier to accept; an inappropriate style or tone impedes acceptance and appropriate resolution. Style varies from one person to another, but a simple, direct approach, void of colorful language, is the most effective way to convey facts.

The tone also should be neutral, not judgmental, convincing in its modesty of language, and not provocative in its descriptions. Style, tone, and clarity must complement one another; each handled well tends to achieve the others.2

Analysis

In most investigations, more information is collected than is necessary to reach a conclusion. Some information is redundant; other information is not pertinent to a decision. Sometimes the information is conflicting.

In cases where remedial, disciplinary, or legal action is a possibility, the decision to accept the conclusions in a report is likely to be made only after an examination of all the evidentiary material assembled. So, deciding what information to treat as evidence and how to deal with it in the report is important.

If the report does not appear to fairly address pertinent evidence, its conclusions may be rejected.

Some common issues include:

1. Evidence considered, but not relied upon, should be discussed in the report if it is likely that others would want to consider it or question the completeness of the report were it not mentioned. This is critical when there is conflicting evidence. The failure to discuss and explain why one version of events is relied upon in lieu of competing evidence will cause readers who are aware of the conflicts to question the objectivity of the writer.

2. Evidence that is redundant or repetitive can be summarized when it comes from various sources that present no unique information.

3. The evidentiary analysis must bring together all documentary, physical, and testimonial facts relating to the allegations to reach a conclusion. The facts relied upon to reach each conclusion should be apparent to the reader. When the applicable standards are themselves vague, or the testimony conflicts, the reasoning that leads to a conclusion is not always apparent. In that case, the analysis in the report must explain to the reader how the investigator reached the conclusion.3

The investigator’s report may consist of a brief summary of the results of the examinations performed on the items submitted for analysis. Again, as with forensic policies, the report will vary drastically between organizations and organization types. A corporate report will have a different audience than one from law enforcement.

The report may include:

- Identity of the reporting agency or requesting department.

- As seen on title page of the exemplar report: “Forensic Investigations, ABC Inc.” (see Appendix) This identifies the “author” of the report.

- Case identifier or submission number.

- Unique identifiers are key in tracking anything, for example unique case numbers for help desk support tickets or security incidents.

- Case investigator’s name.

- Identity of the submitter.

- Date of receipt.

- Date of report.

- Descriptive list of items submitted for examination, including serial number, make, and model.

- Descriptive list of items used to investigate including both hardware and software.

- Brief description of steps taken during examination, such as string searches, graphics image searches, and recovering erased files.

- Chain of custody documentation/form.

- Results/conclusions.4

Ronelle included a copy of the chain of custody (CoC) form with the report, the original remaining with the evidence drive. Ronelle signed the form twice, once upon receipt and once again upon return. Ronelle did not sign the CoC form each time she put it in or took it out of the vault. The evidence vault has its own chain of custody sign in/out form for locking it in the vault or removing it.

When Ronelle eventually returned the evidence drive, the forensic department at ABC Inc. will secure evidence in a vault requiring signatures to check out evidence.

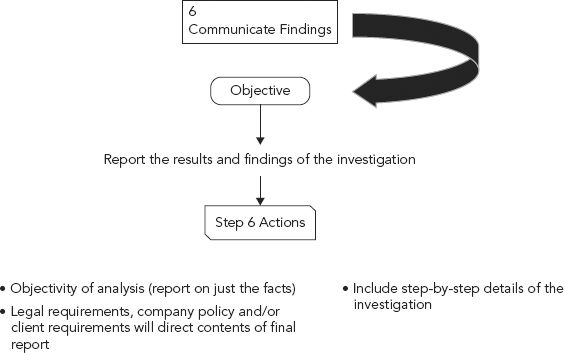

STEP 7: RETENTION AND CURATION OF EVIDENCE

The handling of physical evidence covers a wide variety of activities from the crime scene to the courtroom. In some jurisdictions, this can extend to the period after trial, including the destruction or disposition of evidence.

The evidence should be organized and labeled in such a way as to not alter the evidence and allow it to be easily identified or retrieved at a later date. (See Figure 12.3.)

FIGURE 12.3 Step 7: Retention and Curation of Evidence

The complications in handling digital evidence are increased due to the potential for data replication. When presented with original evidence, an investigator will typically make a forensic image from which to investigate, assuming hash verification of course. Being that the evidence is digital in nature, the forensic image can now also be considered evidence.

Retention of evidence used here implies any of the storage, archiving, destruction, or returning of all evidence. This includes the physical as well as the logical: original evidence, forensic images, hard drives, computers, phones, CDs, tapes, photographs, reports, forensic notes, and so on. Not all case evidence is identical and therefore retention policies may vary between types. For example, after a corporate malware investigation a laptop may be sanitized, reimaged, and returned to the user or perhaps put back into production.

However, the prosecuted in a child pornography case would be wise not to expect a returned laptop. Retention policies will vary even more between different organization types. Also, within the same organization, retention policies for original evidence may vary from those of forensic images or even the final report.

Forensic data retention and archiving policies will depend much upon the type of organization, and may be subjected to existing overriding policies or laws. Depending upon the practice, retention periods can be contractual, corporate policy, or even required by law.

A small, private forensic practice may have in-house policies regarding retention policies unless otherwise specified by contract. All this would have to occur within the boundaries of the law, of course.

Whatever retention is decided upon, the security, organization, and identification of evidence is imperative. The evidence should be stored according to its data classification. If the evidence is confidential then the evidence shouldn’t be stored on a file share accessible to all or in an unsecured file cabinet.

When storing digital evidence, the cyber forensic investigator should:

1. Ensure that the digital evidence is inventoried in accordance with the agency’s policies.

2. Ensure that the digital evidence is stored in a secure, climate-controlled environment or a location that is not subject to extreme temperature or humidity.

3. Ensure that the digital evidence is not exposed to magnetic fields, moisture, dust, vibration, or any other elements that may damage or destroy it.5

Potentially valuable digital evidence including dates, times, and system configuration settings may be lost due to prolonged storage if the batteries or power source that preserve this information fails. Where applicable, those responsible for the transportation of evidence should inform the evidence custodian that electronic devices are battery powered and require prompt attention to preserve the data stored in them.6

Early attention to the difficulties in preserving digital information focused on the longevity of the physical media on which the information is stored. Even under the best storage conditions, however, digital media can be fragile and have limited shelf life. Moreover, new devices, processes, and software are replacing the products and methods used to record, store, and retrieve digital information on breathtaking cycles of two to five years.

Given such rates of technological change, even the most fragile media may well outlive the continued availability of readers for those media. Efforts to preserve physical media thus provide only a short-term, partial solution to the general problem of preserving digital information. Indeed, technological obsolescence represents a far greater threat to information in digital form than the inherent physical fragility of many digital media.7

If possible, commonly used media (rather than some obscure storage media) should be used for archiving. Access to evidence should be extremely restricted, and should be clearly documented. Controls should be in place to detect unauthorized access to archive storage areas.8

While digital evidence obtained as part of a cyber forensic investigation is subject to specific procedures governing its acceptable storage, retention, and archiving, the examination of data retention standards outside of the cyber forensic field can be useful to the forensic investigator in developing comprehensive retention and archiving policies for digital evidence.

ISO 15489:2001

Successful digital curation relies on a robust workflow, which considers the complete lifecycle of a digital resource from inception to disposal or selection for long-term preservation. The development and documentation of policies, responsibilities, authorities, and training schemes for digital resource management is as important as the design and implementation of a system to ingest, manage, store, render, and enable access.

There are many benefits associated with the development, documentation, and adherence to workflow methodologies including the ability to design a system which is effective for all users, the ability to readily comply with legal, regulatory, and standards requirements, asset recognition, and the ability to curate and preserve information over the long term.

ISO 15489:2001 preceded another well-known digital curation workflow standard, OAIS (Open Archival Information Systems Reference Model—ISO 14721:2003). ISO 15489 is considered by many to be more easily understood, as it provides more concrete guidance on the management of records.

Primarily developed for the management of business records, ISO 15489:2001 can be applied to the management of records created by any activity, and is equally applicable to digital or hard copy information.9

The standard provides guidance to ensure that records remain authoritative through retention of their essential characteristics: authenticity, reliability, usability, and integrity. It explains how to ensure records are properly curated, easily accessible, and correctly documented from creation for as long as required.10

ISO 15489:2001 identifies how systematic management of records can ensure that an organization’s, an individual’s, or a project’s future decisions and activities can be supported through ready access to evidence of actions and past business activities, while facilitating compliance with any pertaining regulatory environments. The need for clearly defined and well-documented records management policies and responsibilities, within an organization or project, along with the benefits which will accrue from development and implementation, is outlined.11

Records management processes:

1. Capture

2. Registration

3. Classification

4. Access and security classification

5. Identification of disposition status

6. Storage

7. Use and tracking

8. Implementation of disposition

ISO 14721:2003

ISO 14721:2003 specifies a reference model for an open archival information system (OAIS).

The purpose of this ISO 14721:2003 is to establish a system for archiving information, both digitalized and physical, with an organizational scheme composed of people who accept the responsibility to preserve information and make it available to a designated community.

This reference model addresses a full range of archival information preservation functions including ingest, archival storage, data management, access, and dissemination.

The reference model also:

1. Addresses the migration of digital information to new media and forms the data models used to represent the information, the role of software in information preservation, and the exchange of digital information among archives.

2. Identifies both internal and external interfaces to the archive functions, and identifies a number of high-level services at these interfaces.

3. Provides various illustrative examples and some “best practice” recommendations.

4. Defines a minimal set of responsibilities for an archive to be called an OAIS, and defines a maximal archive to provide a broad set of useful terms and concepts.12

The OAIS model described in ISO 14721:2003 may be applicable to any archive. It is specifically applicable to organizations with the responsibility of making information available for the long term. This includes organizations with other responsibilities, such as processing and distribution in response to programmatic needs.13

The cyber forensic investigator, while not his/her primary job responsibility, should still keep abreast of the chaining dynamics and requirements in the growing field of digital curation.

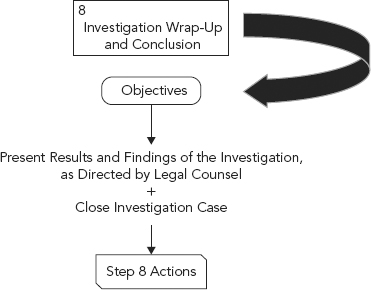

STEP 8: INVESTIGATION WRAP-UP AND CONCLUSION

The wrap-up of any investigation is, again, a nonspecific science, meaning that each company, department, or agency will have, by policy, its own procedures and methodology for winding down, wrapping up, closing out, and terminating an investigation. Granted, some actions taken in this final step may be dictated by law, especially if such investigations will be moving beyond an internal disciplinary action taken by company management to prosecution by local, state, or federal authorities.

However, in general there are typically several common tasks, steps or actions that will constitute the final phase of the investigation, which will consume the investigator’s time and take him/her away from the actual science of performing cyber forensic analysis and investigation. These tasks and actions, however, are as essential to successfully ending an investigation as the steps taken by the investigator in the early stages of an investigation.

Figure 12.4 summarizes these steps and we discuss each briefly here. The reader should be aware, however, that not every action or task discussed here is performed in every organization or even cohesively in a single step as we have presented here. Many organizations may elect to separate some of the tasks shown in Figure 12.4 into independent steps.

FIGURE 12.4 Step 8: Wrap-Up and Conclusion

INVESTIGATOR’S ROLE AS AN EXPERT WITNESS

Before briefly discussing what the investigator’s role and responsibilities may be as an expert witness, we need first to define, exactly, what is an expert witness? According to several real legal type resources, an expert witness and his/her expertise and testimony can be defined as:

1. Testimony in the form of an opinion or otherwise based on scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge; witness must be qualified, as determined by court. Rule 702, Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE).

2. “Unlike an ordinary witness, an expert is permitted wide latitude to offer opinions, including those that are not based on firsthand knowledge or observation.” Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 592 (1993).

3. Another key distinction: expert witness, unlike “lay” witness, may answer hypothetical questions based on information presented at or before hearing, including facts and data not admissible in evidence. Asplundh Mfg. Div. v. Benton Harbor Eng’g, 57 F.3d 1190, 1202 n.16 (3d Cir. 1995); Rule 703, FRE.

One also has to consider the type of testimony to be given by the cyber forensic investigator (i.e., fact testimony, which is testifying solely as to facts within witness’s personal knowledge, or lay opinion testimony, which are opinions or inferences rationally based on witness’s own perceptions and not based on scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge within the scope of Rule 702 [Rule 701, FRE]).14

In any case, taking on the role of an expert witness carries with it significant responsibilities as well as risks.

Role of an Expert Witness

The primary role of the expert witness is to provide the finder of fact with reliable evaluations and opinions that are based on scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge. As explained in Federal Rule of Evidence 702 (Testimony by Experts), expert witness testimony is meant to be substantially useful in assisting the court’s understanding of the evidence and facts at issue. To fulfill that role, the expert witness must deliver evaluations that agree with accepted knowledge and experience. Ultimately, it is up to the finder of fact to determine the reliability, relevance, and weight of the expert’s testimony.15

The lawyer-expert relationship includes a hierarchy and organization that is generally well understood by all involved: the lawyer is in charge of the overall process and provides direction and strategy; the expert evaluates case data and information and presents findings, conclusions, and opinions, in addition to providing technical guidance along the way. This process is simple in appearance only. Litigation that involves the participation of expert witnesses is most often a very complex, lengthy, and tedious process with many variables that can influence the ultimate outcome of a case. Several of the variables are human in nature and often difficult or even impossible to control or predict.16

Deposition Steps Prior to Formal Court Presentation

To reign in “bad science,” courts are empowered to act as gatekeepers to exclude unreliable or irrelevant expert testimony (Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharm., Inc., 509 U.S. 579, 589-90 [1993]). This major change in the law has had some of the intended effects but does not appear to have fully solved the problem. In practice, it is indeed very difficult for a court to fulfill the gatekeeper’s role fairly and effectively, and the gatekeeper function is not applied consistently across all jurisdictions. For the expert, being “Dauberted” is a serious concern that can negatively affect one’s career.

The expert witness is often publicly stigmatized as ethically compromised, considered by some as nothing more than a “hired gun.” This stigma is born from misconceptions and from unavoidable human nature. The concept that anyone who charges high hourly rates would say anything to satisfy the paying party, along with a few well-publicized examples of professional misconduct, serve to anchor this stigma.

In reality, the enduring expert witness must demonstrate strong professional and ethical conduct. The typical expert witness may work for the plaintiff in one case and the defendant in another. The expert witness can ill afford to submit erroneous or exaggerated claims and allegations that are contrary to or go beyond what can be supported by the facts in evidence and by sound scientific or technical methodology.

Doing so may ultimately prove ineffective for the case and trigger appeals. Being exposed as unethical could also spell the end of a rewarding professional career. Opinions of the court and transcripts of deposition and trial testimony constitute a public record. That record serves as an effective quality control tool that lawyers and the finders of fact can consult. To succeed as an expert witness, credibility and thoroughness have to complement education and experience.

There are no universal recipes for delivering effective expert testimony or for a successful professional relationship between lawyers and experts. However, there are a few considerations that often matter.

First, for expert testimony, it is important to:

- Prepare extensively and rehearse the testimony with the trial lawyer.

- Present opinions in a simple manner using easy-to-understand language and demonstratives, regardless of how complex the bases for the opinions might be.

- Address the testimony to the finder of fact.

- Limit answers and explanations to the open question.

- In cross-examination, answer only to the open question, using short answers; avoid being dragged into arguing.

- Reserve detailed explanations for redirect to address the critiques that might have been raised in cross-examination.

- Show respect to the court and observe proper decorum.

Second, for a successful lawyer-expert relationship, it is important for the expert to:

- Be the expert, not the lawyer.

- Adapt to the lawyer’s personality and modus operandi without compromising work performance and quality.

- Deliver work products on time.

- Keep the lawyer informed of progress, setbacks, and other difficulties.

- Keep track of the budget since it can be a limiting factor.17

Securing Access Rights to Case Notes and Related Case Data

All case notes and case data collected and developed by the investigator should be considered first confidential and second proprietary, either of the organization who authorized the investigation or of the entity (local, state, federal) conducting the investigation.

As such, whether as the investigator you are an employee or an independent third-party, it will be essential to ensure that you have addressed the issue of obtaining legal access to all of your case notes, especially if there will be a lapse of time between performing the field-level investigation and the actual presentation of your findings, whether internally to management or in a deposition or court of law.

It is very unlikely that upon completing your investigation there will be an immediate presentation of your findings; there will be a natural time lag between these events. The time lag may depend upon further investigative actions which must be taken by other external entities, a delay to act on the part of management, a backlog of cases preventing immediate response from legal counsel, or a full court docket that delays your appearance as an expert witness in a court of law.

This consideration is critically important, especially as time passes and memories tend to blur and fade, and exact details and critical specifics may only be recalled by reviewing one’s case notes. This is an especially important consideration for those investigators who are internal company employees. How would you obtain access to your case notes if you are no longer employed by the same organization under which you conducted your investigation? If, like most investigators, you are working multiple cases simultaneously, you may have many case notes to which you may require access.

As an independent third party, have you, via contract, stipulated that you may retain copies of all case notes pertaining to investigations performed for clients? Do you have the ability to safeguard these documents while they are in your possession? These case notes and the information contained in them may be considered confidential and removal of such material from an organization or client’s site without prior written approval may be unlawful or even constitute a breach of contract.

In any situation, as an employee or third-party contracted investigator, the ability to recall critical technical information clearly, concisely, and accurately without hesitation will often times depend on access to one’s case notes. Ensuring such access is an important step in the investigator’s overall investigative smart practices.

Depending on both the nature and status of the investigation and legal statute, those data seized, collected, and examined by the investigator may be returned to the data’s owner, held by the investigative department or agency until the case goes to trial, retained by the cyber forensic investigator, or disposed of and destroyed according to instructions from legal counsel and company policy.

Closing Out Case Files

This step will certainly be guided by department, agency, or company policy. Cases may be closed, for example, based upon a final adjudication in a court of law, decision on the part of management not to take any additional or further action, or advice from legal counsel as to the appropriateness and viability of the evidence collected to withstand a successful presentation at trial.

Once a case is closed and the investigator’s files, records, notes, reports, and transcripts have been delivered to the case manager, legal counsel, or management representative, the investigator’s responsibility is now complete. Responsibility for the safeguarding, handling, transportation, archiving, and disposition of these files now rests with the recipient.

Whether you are an employee or a third-party contracted investigator, you have one last task to perform, however. You must obtain sign-off from the recipient of:

1. A receipt log, detailing all files, records, notes, reports, and transcripts turned over by the investigator. This receipt log, in addition, should show the case number, recipient’s signature, and date.

2. If not a formal internal document, then a letter from the recipient, containing the case number, recipient’s signature, and date stating that the case has been officially closed and that there are no outstanding issues or items requiring further action on the part of the investigator.

Post-Investigation Quality Control Assessment and “Lessons Learned”

Investigative smart practices warrant that the overall investigative process should contain an ability to continually look backwards on the process, for evaluative and assessment purposes, with the overall objective of continuous process improvement.

The final step of the investigation process entails, to the degree dictated by organizational policy or mandated by legislation, a quality control and assessment activity.

First, a few definitions are helpful:

- Quality assurance activities include planning for quality management activities and verifying that those activities were carried out.

- Quality control activities include the actual implementation of quality management activities and the documentation thereof.

The quality assessment/control process may or may not be conducted by the cyber forensic investigator, may be conducted independently or via a team review process, and may be preformed internally or through an independently contracted third party. Regardless of the approach, performance of such a review process is essential in ensuring that investigative policies and procedures followed conform to guidelines set forth by legal precedent, management policy, and generally accepted cyber forensic investigative practices and professional due diligence.

A viable quality assessment/control process should specify the organization, procedures, documentation, testing, and methods to be used to provide quality, in accordance with sound investigative policies, guidelines, and proven cyber forensic investigative methodologies.

A typical post cyber forensic investigation program should address, but not be limited to, the following elements:

- Management responsibility

- Investigator responsibility and competencies

- Investigative process and procedures

- Evidence identification, acquisition, traceability, retention, and disposal

- Evidence control

- Inspection, measuring, and testing of forensic diagnostic equipment and software

- Final report documentation, distribution, and control

- Maintenance of assessment records

- Continued investigator training

- Corrective action to policy, procedure, and methodology as required

- Directives for ongoing quality and assessment audits

The ability to substantiate a continuously examined and quality cyber forensic investigative process is essential in establishing and maintaining the ongoing credibility of digital evidence obtained through that process.

As a cyber forensic investigator your report must communicate all findings in an objective manner, as it may be used in a court of law and you may be called as a witness (expert or not), to defend it. It is better to overdocument than not; thus, always err on the side of caution and overdocument. It is not an insult to a cyber forensic investigator to be called thorough, careful, meticulous, or methodical; this is especially true when you are called to the witness stand.

Deciding what to do with collected evidence after an investigation is closed is a critical issue that must be addressed through well defined, well established, and implemented policies.

Continuous self-assessment of the personnel, processes, procedures, policies, hardware, software, and methodologies used to conduct each cyber forensic investigation is essential in establishing the credibility of evidence brought forth by the cyber forensic investigator, through the investigative process.

1. Office of the Naval Inspector General, Investigations Policy Manual, Chapter 8—Report Writing, July 1995, retrieved September 2011, www.ig.navy.mil/Documents/Downloads%20and%20Publications.htm, used with permission.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Forensic Examination of Digital Evidence: A Guide for Law Enforcement [NCJ 199408], U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC 20531, April 2004, retrieved September 2011, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/199408.pdf.

5. Electronic Crime Scene Investigation: A Guide for First Responders, Second Edition, U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 810 Seventh Street N.W., Washington, DC 20531, NCJ 219941, April 2008, retrieved September 2001, www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/219941.pdf.

6. Ibid.

7. Preserving Digital Information Report of the Task Force on Archiving of Digital Information, commissioned by The Commission on Preservation and Access and The Research Libraries Group, May 1, 1996, retrieved September 2011, www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub63watersgarrett.pdf.

8. D. Brezinski and T. Killalea, “Guidelines for Evidence Collection and Archiving,” RFC 3227, The Internet Society, February 2001, retrieved September 2011, http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc3227.

9. S. Higgins, “ISO 15489,” Digital Curation Centre, Appleton Tower, 11 Crichton Street, Edinburgh, EH8 9LE, retrieved September 2011, www.dcc.ac.uk/resources/briefing-papers/standards-watch-papers/iso-15489, used with permission.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. H. Bowden, H. “OAIS Reference Model—ISO 14721:2003,” The Digital Curation Exchange, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Information and Library Science, November 27, 2009, retrieved September 2011, http://digitalcurationexchange.org/node/1079.

13. Ibid.

14. “Expert Witnesses: Ethics In Court: DO-07-019a: Attachment to DO-07-019,” U.S. Office of Government Ethics 1201 New York Avenue, NW. Suite 500 Washington, DC 20005, retrieved October 2011, www.oge.gov/OGE-Advisories/Legal-Advisories/DO-07-019a--Attachment-to-DO-07-019.

15. R. Hennet, “Working with Lawyers: The Expert Witness Perspective,” Expert Witnesses United States Attorneys’ Bulletin 58, no. 1 (2010), published bimonthly by the Executive Office for United States Attorneys, Office of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, Columbia, South Carolina 29201, United States, Department of Justice, Executive Office for United States Attorneys Washington, DC, 20530, retrieved October 2011, www.justice.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_room/usab5801.pdf, Dr. Remy J-C. Hennet is a Principal at S.S. Papadopulos & Associates, Inc. (SSPA), headquartered in Bethesda, MD; used with permission via discussion with author.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.