Opportunity Costs: Prudence versus Returns

There is, unfortunately, a trade-off between the soundness of investment decisions made by a family and the speed with which those decisions must be made to be effective.2 All too often, in other words, there is a conflict between a family's desire to be prudent in its decision making and the family's desire to achieve competitive returns.

In the fiduciary world, over the course of several hundred years, standards of fiduciary prudence have become ever more process oriented and ever less outcome oriented. The main reason for this is that, under traditional trust doctrine, a trustee was absolutely liable for almost any loss of principal: “Traditional trust doctrine caused ultimate liability for losses to the trust to sit like a devil on the shoulder of every trustee.”3 As a result, trustees typically invested only in gold-plated investments, such as gilts (debt securities issued by the Bank of England).

The traditional rule was very much outcome-oriented: Allow the capital to decline in value and you will be held liable. Interestingly, this situation began to change when trustees in the United States found that there was no domestic counterpart to gilts: Bonds issued by the new United States were too risky! This circumstance “encouraged the majority of American fiduciaries to direct their investments toward promoting nascent industrial enterprises”4 in the United States, and this in turn caused American courts to revisit the absolute liability rule that applied to English trustees. The new American approach looked to process, rather than outcome.

Prudence versus Returns for Trustees

In the remarkable case of Harvard College v. Amory, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts rejected the English doctrine of strict trustee liability, adopting instead the so-called “prudent man rule,” which was not outcome-oriented (“Did the capital lose value?”) but process-oriented (“Did the trustee behave responsibly?”):

All that can be required of a trustee to invest is that he shall conduct himself faithfully and exercise a sound discretion. He is to observe how men of prudence, discretion and intelligence manage their own affairs, not in regard to speculation, but in regard to the permanent disposition of their funds, considering the probable income, as well as the probable safety of the capital to be invested.5

In other words, Justice Chase was saying, “Don't look at the investment result. Look, instead, at whether or not the trustee was proceeding sensibly.”

The Harvard College case proved to be a flash in the pan, however, as other jurisdictions refused to follow it. Courts, to say nothing of beneficiaries, weren't all that interested in how procedurally prudent trustees were being; they were interested in keeping their capital intact.

By the end of the American Civil War, therefore, U.S. trustees were pretty well limited to investing in government bonds and mortgage-backed corporate debts. Invest in anything else and trustees found themselves absolutely liable for any diminishment of value. Indeed, by the 1880s, many states had adopted “legal lists,” that is, lists of securities trustees were permitted to buy (mainly fixed-income debt instruments and bonds).

Gradually, however, things began to change, which is to say that they reverted back to the process-oriented “prudent man rule” first laid down in the early nineteenth century. The development of the modern, postindustrial economy vastly complicated trustees' lives, squeezing them between beneficiaries who wanted higher returns and fiduciary rules that limited trustees to bonds. Of course if trustees were going to shoot for the higher returns available in equity securities, they were sometimes going to fall short. Something had to give.

At roughly the same time, and impelled by roughly the same developments, modern portfolio theory (MPT) arose. Whereas traditional trust doctrine required trustees to avoid risky investments, MPT taught investors to profit by them. MPT distinguished between systematic (or market) risk, for which an investor was compensated, and specific (or residual) risk, which must be diversified away. MPT argued that a true understanding of diversification would allow investors to add risky assets to a portfolio while actually reducing (or at least not increasing) overall risk levels.

Today, the Restatement (Third) of Trusts articulates the “prudent investor rule,” whose main feature is that—as in Justice Chase's formulation back in 1830—we are asked to look not at how the capital performed but at how the trustee behaved. Here is the core of the rule:

The trustee is under a duty to the beneficiaries to invest and manage the funds of the trust as a prudent investor would, in light of the purposes, terms, distribution requirements, and other circumstances of the trust.

This standard requires the exercise of reasonable care, skill, and caution, and is to be applied to investments not in isolation but in the context of the trust portfolio and as a part of an overall investment strategy, which should incorporate risk and return objectives reasonably suitable to the trust.6

Nowhere, I note, does the prudent investor rule suggest that a competitive return on the capital should be any part of the analysis.

Prudence versus Returns for Families

Let's assume for the moment that, in the fiduciary context, it makes sense to elevate process over outcome—otherwise, trustees would shrink from taking risk, as they did for centuries. Outside of the fiduciary context, in the world of private family capital, legal liabilities are very different and therefore the relative emphasis I place on process versus outcome should also be different.

Yet, when we look at how wealthy families behave, we find that they are also encouraged to elevate process over outcome. Pressed by well-intentioned financial advisors, family investors who aren't fiduciaries in any legal sense have gone to great lengths to draft mission statements and investment policy statements, have laboriously created investment committees, and have encouraged inclusiveness by bringing in the ideas and concerns of many different family units and generations. These families are, in effect, mimicking the behavior of legal fiduciaries by focusing mainly on the procedures that will be used to make investment decisions.

Just as a thought experiment, let's consider whether this obsession with process is entirely wise.

Families and their advisors are spending so much time on process because they believe that sound, prudent procedures will inevitably lead to good investment outcomes. But will they? Certainly they don't in the fiduciary arena. Every corporate trustee in America, for example, is deeply schooled in prudent processes, yet the vast majority of them underperform, say, the Vanguard STAR Fund,7 a simple, inexpensive option that costs a small fraction of what trustees charge and beats the pants off almost all of them.

I'm not arguing for dysfunctional family investment procedures. Certainly it's true that families with alarmingly dysfunctional behaviors almost always experience bad outcomes. However, it's also true that many families who have developed extremely thoughtful, highly prudent, thoroughly inclusive procedures find that their investment returns are far below par.

What's going on here? The simple answer, I suggest, is that these families have overlooked the importance of opportunity costs. Technically, “opportunity costs” refers to market price movement that occurs between when somebody comes up with an investment idea and when they get around to executing it. In rapid-fire computer trading strategies, thousands of trades are executed on a split-second basis to try to take advantage of small and fleeting price disparities. The opportunity costs associated with the loss of even a second or two can mean the difference between a profit and a loss.

In a more typical situation, good advisors' investment ideas tend to be good ones when they're formulated, but those ideas will degrade in value over time, as other, less insightful investors belatedly pick up on the idea. What was a good idea on January 1 tends to be a less good idea on January 15 and tends to be a bad idea in March.

Sound, thoughtful family decision-making processes are crucial to holding a family together, especially during stressful periods of time, and they go a long way toward enabling families to keep their legacies intact. But if the procedures are ignoring opportunity costs, the game may not be worth the candle: Nothing breaks up a family more quickly than poor investment performance.

Ask yourself if your family makes investment decisions like this: Investment ideas are communicated to your family by your advisor; your family takes these ideas under advisement; the ideas are forwarded to the family's investment committee; Uncle Ralph, who hates hedge funds, weighs in from his safari in Africa; somebody checks the policy statement and notices that not enough notice has been given to younger generations to review the recommendations; Uncle Ralph will return from safari next month, so why rush into a decision he's likely to oppose? And so on.

Like it or not, every day we spend being prudent is a day that our returns go down, because our investment ideas are going stale while we are waiting to implement them. Add these opportunity costs up over the days and months and years and we have a seriously underperforming portfolio.

Ah, you are thinking, but by intensely reviewing my advisor's recommendations, I'm weeding out the bad ones, and that will offset the opportunity costs. If that's the case, you need to fire your advisor. Looking back over 30 years of working with families, I observe two things. First, families almost never disagree with a good advisor's recommendations—they just implement them too slowly. Second, on the rare occasions when families overrule advisors, the families are usually wrong, thereby compounding opportunity costs with bad investment decisions.

The problem has to do with the respective skill sets of families and advisors. Just as it's true that a lawyer who represents himself or herself has a fool for a client, a family that thinks it knows more about investing than its advisor needs a new advisor. Family members often believe that they aren't doing their job unless they review and discuss every action ad nauseum before allowing their advisor to implement it. This ignores the realities of the marketplace and, especially, it ignores the relative skills and experience of families and investment professionals.

Striving for Prudence and Returns

For wealthy family investors, there is a serious tension between two important aspects of the investment process: on the one hand, following thoughtful, sensible procedures and, on the other hand, achieving good investment returns. How might I reconcile these tensions?

The critical issue, I suggest, is to identify what it is that families do best and what it is that investment professionals do best, then assign those tasks appropriately.

Many of the most critical activities associated with the management of private capital have no particular time pressure associated with them. For example, establishing an appropriate risk level for the capital is the single most important thing a family can do. That task requires a lot of soul searching by family members and a lot of discussion among family members and between families and advisors. Ultimately, all of this work results in a policy statement in which the key risk metrics are written down. Once this has been accomplished, all the family has to do is to review the policy regularly.

Similarly, the family needs to monitor investment performance, but short periods of performance are mainly irrelevant, so there is little time pressure associated with performance monitoring.

Finally, the family should always be striving to improve its understanding of the investment process and capital markets, but educational sessions, outside speakers at family meetings, and so on are not time sensitive.

Note that most of the issues I would assign to the family not only address broad-but-critical issues, they also address principal/agent issues. No matter how good your advisor is, the interests of an advisory firm and the family whose principal is being invested can never be identical. By carefully considering the long-term strategic issues associated with wealth management and writing them down in a policy statement, the family will have gone a long way toward aligning its own interests with those of its advisor.

By the same token, issues such as manager selection and replacement, tactical moves in the portfolio, and implementation of opportunistic ideas have serious opportunity costs associated with them and should be left in the hands of the professionals—subject, of course, to the family's investment policy statement and to the family's obligation to monitor the advisor's performance. If an advisor takes an action in violation of the policy statement, it must be undone at the advisor's risk. Even if the action doesn't violate the family's policies, but simply makes the family uncomfortable, the advisor should reverse the trade at the family's risk. (Both of these events should be extremely rare.)

As noted in Chapter 6, many families avoid opportunity costs by outsourcing the investment function to an outsourced chief investment officer. Note that complete outsourcing is not required. All that is required is that the various activities that make up the total management of the family's portfolio be allocated between the family and its advisor appropriately.

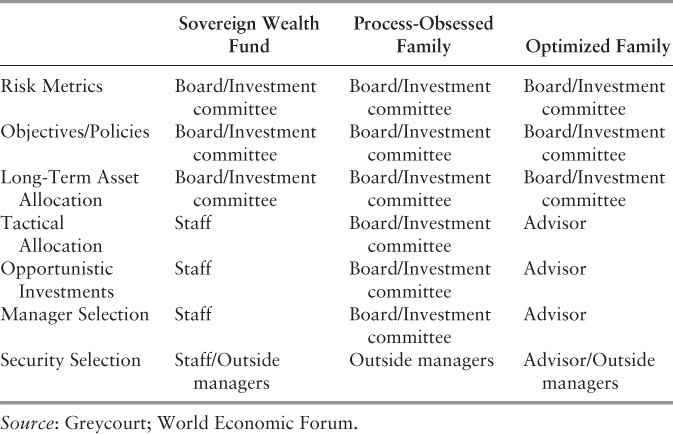

A good working example is offered by very large institutional investors, such as endowments, pension plans, and sovereign wealth funds. Best practices at such institutions allocate investment responsibilities between the institution's board (or investment committee) and the institution's in-house investment staff exactly as suggested above: The board sets long-term risk targets and investment objectives and policies, and establishes strategic asset allocation guidelines. The staff selects managers, negotiates mandates, shifts the portfolio tactically within the bounds set by the institution, and implements opportunistic investments (again, within the limits established by the policy statement).8 By analogy, the family is the board and the advisor is the investment staff. This allocation of responsibilities is illustrated in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 Investment Decision Making