Chapter 2

The Need for Laddering

Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.

—Dorothy, The Wizard of Oz

I’VE ALWAYS BEEN a great swimmer and feel at home in any kind of water: beach, lake, pool, or river—you name it. My dream is to live by the water and walk on the beach every day, and my favorite form of exercise is swimming laps at a local pool.

I was, apparently, a fan of the water my entire life. My parents tell stories of me as a toddler running toward the pool and jumping in at full force, unaware—due to my lack of experience—of the dangers that existed. I went on to become a very good swimmer and spent my elementary years at the pool and participated in our neighborhood’s swim team.

However, I can distinctly remember one instance where the water became a new and frightening environment for me, different from the familiar one I’d come to know. I was nine years old, visiting a local water park and playing in one of those huge wave pools. With each crashing wave, an undertow pulled me farther and farther out to a sudden drop-off in the pool that put the water well over my head. I was out of my mother’s reach and in serious trouble. Luckily, she quickly realized I was in trouble and jumped into action. She had the strength to pull me back to safety, but not before I took several gulps of water and saw my short life flash before my eyes.

This is what has happened in the world of product development and marketing in the past few years. The calm, predictable waters—that is, the formulas that have worked for decades to predict sales and adoption—are no longer enough to be successful. As a result, today’s marketing and product development managers find themselves in the same predicament as was I in that wave pool: they are in over their head, being pulled farther out and being asked to support more and more technology. They need to create products that still appeal to a wide group of people while analyzing a growing mountain of data. They are looking for a lifeline, a way to get their head above water, find their footing, and understand the new way forward.

The initial cracks in the old way of building and distributing products came with the introduction of the iPod in October 2001. Even though it was a mass-produced item, it disrupted a single industry by fundamentally changing the way we bought, consumed, and shared music. Yet what some people don’t know is that Apple wasn’t the first company with an MP3 player on the market. SaeHan, an electronics device company, was selling one in Asia called MPMan as early as the spring of 1998.

What Apple did that SaeHan missed was make it easy for users to include this product in their lives in the way the consumer saw fit. And soon enough, we were hooked on this new gadget, with very little overt direction from the product creator on how to use it. The technology for accomplishing this was truly as simple as plug and play, and instead of selling it to us based on gigabytes or RAM or through any other technical jargon, Apple simply let us know that as a user, you could have “1,000 songs in your pocket.” The iPod’s advertisement emphasized the joy of listening untethered to our own music through iconic white earphones. None of these advertisements included the technical jargon usually associated with a technology product. They simply showed a darkened shadow dancing to music; the only words that ever appeared were iPod or iPod + iTunes.

Before the iPod came along, recording artists carefully compiled their playlists. But this new device did something seemingly revolutionary: by providing iTunes, an easy-to-use software product, it allowed us to create our own playlists based on our desires or mood, thereby allowing us to craft our own experience. As a result, many of us may never buy an entire album again—and we certainly wouldn’t listen to it in the way that had been dictated by the artist in the past.

Then Apple upped the odds even further with subsequent versions of the iPod, adding video, increasing storage, and decreasing its footprint. Soon, this vehicle of experience and customization became virtually everyone’s must-have item.

But the crashing waves didn’t really hit until June 29, 2007. That was the date when Apple introduced a product that—in a very short timeframe—fundamentally changed the way we could customize devices that we carry with us everywhere: the iPhone.

Before this point, every phone that was manufactured had to contain common elements: buttons, placement of icons, and even applications. There was no way to customize the experience at the base level in the way that the iPhone and other smartphones eventually accomplished.

Back then, a lot of phones looked the same. But today, if you took a picture of the main page of everyone’s smartphone, you’d find that no two were alike. If you looked closer and began to determine the types of apps that were on each, you would be able to identify patterns by analyzing what individuals are including on their phones. No two smartphones contain the same apps, and even if they did, there’s a good chance those apps are not being used in the same way or for the same primary purpose.

The introduction of smartphones combined with countless apps, social media, e-books, a fundamentally changed economy, and a constantly maturing, ever-present Internet have provided us with the ability to access information and data anywhere, anytime. It’s no wonder we have been left gulping for air with little understanding as to what just happened.

The world has changed—dramatically.

And thanks to these changes, companies that have traditionally developed and marketed products and services based on market segmentation and demographics are floundering. Their assumptions that their products’ features, functionalities, and messaging will meet all consumers’ needs in a given demographic—a one size fits all mentality—no longer works.

Some companies continue to believe that they will magically be able to go back to the good old days by mining their big data to look for patterns. They believe they can return to a time when it was enough to simply add their system-collected knowledge to what they gathered from census data or transactions, and then use the results to peg and speak to their end consumers. Back then, companies needed to know only that a person was at certain life stage or had a certain purchase history in order to reach him or her and be successful. That no longer gets the job done.

In today’s many-to-many world, users group themselves largely based on values, interests, and aspirations, not according to traditional segmentations of sex, race, and age. You must understand these consumers at their core, that is, what drives them and how they act (and want to act) within certain contexts. You will learn as we talk about this new approach that consumers are far more driven by their desire to share, their desire for authenticity, and their need for relationships. And although this new consumer mind-set was unleashed by advances in technology, it goes beyond technology-based products, solutions, and experiences.

Companies must also realize that they can no longer rely on reaching consumers through mass media channels or influencing via testimonials, celebrity endorsements, or other traditional tried-and-true ways to promote and sell products and services. Much of what affects people’s buying decisions today is invisible and unseen; it’s private and something that only the specific consumer knows. Today’s drivers can be as simple as getting a recommendation from a blog or a tweet from an author upon whom the consumer relies—because they feel like they are alike. It can be a desire to stay connected in the physical world with those they love and care about. It may even be in pursuit of satisfying some deeper need of understanding or acceptance that they carry with them and seek to satisfy by the way they relate to the world around them.

The Answer: Laddering Your Consumer

Technology is no longer the complicated part of the equation; today, it is a given—even easy. Much of the technology currently available is almost as easy and intuitive for us to use as a doorknob or a pencil. There are proven, known ways to make the technology work, so focusing on best practices here would be somewhat of a fool’s errand.

The fact is that humans are good at picking up and using new tools. We adopt them into our environment and start using them to accomplish the task at hand. But because this comes so effortlessly to us, we tend to ignore the larger impact the tool may have on us. And if it’s hard to recognize these changes in ourselves, it’s even harder to discern them and their impact in others. That’s why this most recent disruption’s effects on us have been so difficult to recognize and sort out.

Think about how you would survive a day at the mall without your cell phone. From making a simple phone call, to finding the store that has what you need, to texting back and forth regarding meeting up with friends, and to ensure no one is duplicating a birthday gift purchase. Consumers of all stages of demographics quickly and effortlessly include the cell phone and its many facets of utility into their lives—and can’t imagine what life was like before them.

We must therefore start focusing on what’s complicated: us, the consumer, the user. The adage “Know thy user” has never been more important than it is now—and will be ever more important in coming years.

Companies must now understand their users’ behaviors and core motivators—that is, know the whys behind consumers’ actions. Only after understanding this and figuring out how to insert themselves into the consumers’ existing buying journey will companies be able to establish what consumers really want, which, in most cases, is a relationship. In a relationship, the company understands when to deliver the right message to the right person at the right time and across the right channel. The company can anticipate the consumer’s needs and add the appropriate functionality, features, and experience to their products and services.

Today’s connected consumers demand more from companies than a reliance on demographics, segmentation, or other big data will reveal. They have very specific expectations of brands to provide them with a product, service, or experience. The recent dramatic disruptions in the buyer journey means that companies can no longer rely on previously proven models of reaching their consumer audience or expect these consumers to follow the traditional path from identifying a need to making a purchase.

As I see marketing venture into collecting more and more data on those they are selling to, I notice that they’re just like I was as a nine-year-old in a wave pool: they are jumping into something and not fully sure of what they are getting into. Many expect that they will somehow be able to unlock what everything means and discover how to react once they have determined the data’s patterns.

But this isn’t how it works. Some of these patterns no longer matter, whereas some others mean virtually everything. As this land grab for big data continues, the companies that can unlock the important patterns through the filter of the consumer will be the winners.

The purpose of this book is to do just that: to discuss the patterns of consumer behavior that are truly important—what I call consumer DNA—and to understand how to determine your own consumer’s unique DNA and capitalize on it for successful products, service, experiences, and marketing messages.

In the upcoming chapters, I will discuss the specific steps you can take to start laddering your consumers to understand them. Before we discuss the specific steps and the process, I will cover important aspects of laddering.

Laddering Is Continual Learning

Most companies I work with tend to ask at the beginning of every laddering engagement, “How long is this going to take? When will you know something?”

My answer is always, “I will know what I know when I know it.”

It’s a lot like the concept of balance; no one can explain it. You can’t see it; you just know it after you’ve achieved it through practice. You have to think about the concept of laddering the same way. You don’t know what you have until you have it.

Of course, there are some rules of thumb and proven approaches to laddering your consumers. You must keep in mind that it’s about getting beneath the core drivers and motivations to understand why consumers behave the way they do. What are they trying to express or accomplish? What do they really want?

Answering these questions requires a fairly broad approach—one that strives to truly understand the consumers you want to reach. There needs to be an understanding relationship between people, brands, and products in order to thrive in today’s economy. Although many people claim that this kind of relationship was destroyed by the Internet and associated technologies, it is actually more important today than it’s ever been before. The difference is simply that the Internet, and in particular social media, has changed the way we form, foster, and rely upon these relationships in a very powerful way. We connect with people based on common interests and beliefs, and others’ influence on us is strongly based on how much those people care and foster their bonds with us.

Laddering Uncovers Relationship

We see this desire for relationship and understanding in the ways people use technology and social media. It’s never been easier to connect with other people in general; specifically, our ability to discover and interact with those with whom we share common interests is supported in newer, more interesting ways every day.

Consider the website Pinterest, which was introduced in closed beta in March 2010 and is used largely for the visual collection of images—images of ideas, aspirations, inspiration, and achievements. The segmentation here isn’t based on age, gender, or location, but rather on what people like to spend their time doing, seeing, eating, and so forth. So many people have used their boards to share ideas for their upcoming nuptials that there is a start-up company taking the Pinterest idea a step further by creating a “Pinterest for Weddings.”

Google+ is another technology that’s touted as a backbone for the Internet, helping people find connections to others with similar interests, thereby making everyone’s recommendations more appropriate and useful. Because so many of us have learned to group people based on demographic characteristics, segmentation, and lifestyle, I was guilty of this myself when I first set up Google+. I used categories such as:

- Atlanta

- Entrepreneurs

- User Insight

- User experience

For Google+ to be most effective, I should really sort my circle more like this:

- Foodies (people who like restaurants and food similar to my taste)

- Music (people who share my taste in music and concerts)

- Travel (people who share my interests in travel locations and experiences)

By using this approach, I get much better recommendations in my Google results. Organizing people based on segmentation or demographic data is not as helpful, because I only care to receive suggestions from people who I know are like me within certain contexts—and my age, location, and job aren’t often important. For instance, I’d much rather get a recommendation for restaurants or food experiences from a fellow foodie versus a fellow entrepreneur.

This is a simple example of how an individual can use laddering. Once you are in relationship with others, you automatically start to sort their recommendations and follow their actions based on how closely you think they map to your own personal beliefs, preferences, and points of view. It’s something you do subconsciously, because it’s how you learn to survive and thrive in your environment.

For marketing and product development to get it right as they move forward, they need to understand where their product and/or brand fits in relation to consumers who naturally associate themselves with the brand. Companies cannot force their goods on an end consumer; rather, consumers carefully choose what they want to include in their lives in the same way they choose the friends they hang out with.

Executing laddering properly takes a methodical effort. Once you figure it out, you can rely on the results for many years to come.

I’m frequently perplexed by the approach that some companies take. There are so many that don’t think twice about spending the money and effort required to build a safe, reliable product yet hesitate to take the time and effort to make sure they are building products the end consumer really wants. I have the same opinion about the number of dollars that exchange hands in the advertising and marketing space solely based on demographics and Nielsen ratings. This disregard for knowing the end consumer is the result of so many companies’ inability to understand and react according to today’s changed environment, particularly in the marketing and product development space.

Laddering Is Long Lasting

How long will this work last? I always get this question at the end of a presentation or a specific laddering exercise.

The great thing about laddering is that it’s based on an individual’s core, something that rarely, if ever, changes. If it does, it takes a dramatic disruption. Often, marketers confuse the concept of a person’s core with life stage because life stages often come with a change in the fundamental way that a cluster (distinct consumer groups that map to one another because of their core DNA or behavior) approaches a problem.

For example, a newly married couple may change their spending habits because one of them is a saver and the other is the spender. If the couple chooses to save, the spender in the marriage will begin to manifest spending in a different way. We have seen spenders use coupons and point collection or rewards programs to support their underlying desire to continue to spend. None of these activities are actually saving, though; they are just special ways of spending. Savers never spend their money; they get their satisfaction from watching their money grow. No matter how good the coupon or the deal is, savers will find a reason to delay the purchase. Marriage and other life stages do not change their core.

Laddering Establishes a Common Language

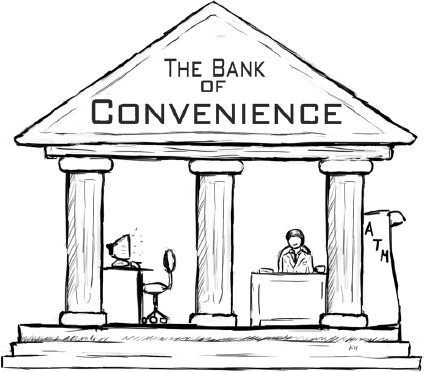

Consider the topic of banking. Most banks’ messaging has focused on life stage drivers. Newly married? Saving for retirement? Time for college?

However, we gathered some interesting information in our laddering work in the space of financial services, specifically as it relates to choice or acquisition of a bank. As it happens, the drivers behind this choice fall into three large categories that have nothing to do with one’s life stage.

To get to these three categories, we had to dig underneath a word that kept coming up over and over again in our conversations with consumers: convenience. Everyone told us that they choose a bank or financial institution based on this word, but convenience means something different to different people. If we had followed the standard quantification and segmentation studies surrounding bank choice as being driven by a life stage, we likely would have identified the word convenience, but we would have risked recommending messaging similar to this:

- ABC Bank has the most convenient process for consolidating your bank accounts after marriage.

- ABC Bank makes it convenient for you to plan for your retirement.

- The most convenient college savings accounts are found at ABC Bank.

But this wasn’t the answer. Convenience means something different to three distinct groups, and it doesn’t matter if you are a baby boomer or a Gen Yer; bank choice is based on one of the following drivers: locations and branches, online tools, or personal relationship.

- Locations and Branches: Consumers who define convenience as locations and branches are family-centered and spend a lot of time with relatives and in their community. They are constantly on the go, heading to school, sports events, and church activities. To them, banks are a physical space, and it’s important to have convenient access near both home and work. They like that the tellers recognize them when they are at the bank and enjoy the person-to-person interaction when they are making a transaction. They don’t see banks as the place for “important” financial matters. They prefer to handle such things themselves or use a secondary brokerage firm or financial planner. A move to a new town might mean a change in banking relationship if their current bank doesn’t have physical bank locations (ATMs, branches) readily available.

- Online Tools: Consumers who define convenience based on online tools will describe their lives as busy with friends, family, and work. The Internet and other task-specific apps are great tools for helping them stay organized, efficient, and informed. They research everything online and are savvy, efficient online shoppers. They spend time reading reviews and comparing options before making a final choice. They love their bank or financial institution because of the tools they provide, but they rarely, if ever, actually visit a branch. In fact, they are more likely than the other two groups to use a bank that doesn’t even have nearby physical branch locations or ATMs. The uncoupling cost to this group for switching banks is high, because they have invested so much time and process in existing online tools such as bill pay. They are open to push messages regarding new products and services if those messages are specifically tailored to their needs. After all, their bank knows a lot about them. They feel that the bank should therefore use this information to enhance their messages’ relevance, ultimately saving this group time.

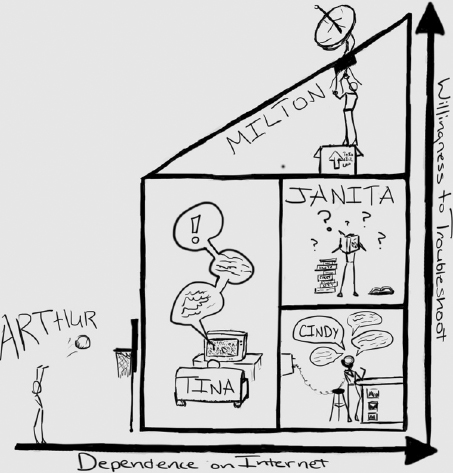

- Personal Relationship: Convenience for third group is determined by personal relationships. They have a more complex financial picture, perhaps from receiving an inheritance, starting a small business, or achieving other financial success, and time is truly a finite commodity. They spend time online but not on research or comparison activities. They have a network of trusted advisors who help point them to others who will meet their needs and provide the high-touch personal relationship they desire. They expect to be able to call or e-mail a specific individual within the bank to take care of their needs, and this person should already know their unique situation without explanation. They will switch banks only for a better relationship. The consumers would enter the banking choice in three different ways as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Convenience is the Core Driver Behind Bank Choice

It’s crucial to define broad, everyday terms such as convenience according to what the consumer or end user really means. It’s easy to take common words and assume a definition. But understanding why a person uses that word—and what value it has to his or her core needs—is the real solution to building messages and products that resonate with your consumer groups.

These consumer groups’ core preferences are not likely to change; therefore, the laddering results will apply for a long time to come. The only reason to do another laddering project would be if another disruption hits the space. For example, the growth of the Internet in the mid-1990s created one of these groups—the group that equates convenience to online tools. Of course, disruptions can be factors beyond technology. This project was completed at the same time that the economic meltdown occurred. We had to account for the disruption around banking and trust of banks. It would also make sense to revisit the research to see if social media or mobile apps have had any impact on how these groups define and expect relationship with their banks today across these new mediums. The base knowledge provides a great starting point to build upon and test some hypotheses.

Laddering Uncovers Influence

One of the traps I often see companies fall into when starting a laddering project is to focus on the size of the groups (clusters). Although the question of size is important, it’s not as crucial as it was in the days of quantification and segmentation. What’s much more important now is an understanding of influence.

We have worked on projects where the size of a group was too small to be considered significant for a brand based on the rules of quantification and segmentation. However, if we had ignored the group, the product or campaign would have been a complete failure. It’s therefore crucial to understand the following as you undergo the laddering exercise:

An understanding of this relationship—and the connection to your product or brand that flows from it—is far more important than any number can express. There are countless examples today of how influential just one person can be, especially given our ability to easily broadcast our messages far and wide.

I recently attended a panel on Pinterest at Digital Atlanta, an annual conference in Atlanta, that highlighted how powerful a single person can really be in our new highly connected society. Kirsten Kowalski was a participant on the panel about Pinterest and shared the following experience:

Kirsten is a photographer and a lawyer who decided to read through the image use policy of Pinterest. After doing so, she penned the blog post “Why I Tearfully Deleted My Pinterest Inspiration Boards,” posted it, and then went to bed. She awoke the next morning to find that her website was no longer working. Assuming that it was merely a technology glitch, she called her web host provider, who informed her that she had surpassed the allowed traffic to her site overnight.

Kirsten’s blog post had gone viral. She had more than 700 responses from others across the web regarding her decision. She even received a call from Pinterest founder Ben Silbermann to discuss her concerns. The site probably didn’t expect one person’s words to influence the Pinterest ecosystem so significantly. By spending time early on to understand Kirsten and others like her, Pinterest may have been able to craft language that was more palatable to people who held the same core drivers—mainly, a desire to do what was right. The good news is that Pinterest reacted quickly and correctly to the post and participated actively in the resolution.

Before undergoing the exercise of laddering your consumers and putting them into their discrete groups, you must rethink everything you have considered about large quantification studies and work to understand and anticipate the new power and reach of the individual.

The Need for Laddering the Consumer

Important changes have taken place in our world that impact the way we interact, both with it and with one another. These changes call for innovative methods to function and operate, especially when it comes to creating new products, services, experiences, and marketing messages. In the next chapter, I will cover the concept of laddering, how it’s been used in the past to sell what could be produced, and how it can be used to understand what’s most important now: the consumer.

- The introduction of disruptive technology such as smartphones and social media has forever changed the consumer landscape by allowing consumers more choice and individual customization.

- Relying on group size to predict consumer behavior is an outdated and dangerous approach; it leads brands to create products and services based on drivers that are not important to their consumers.

- Consumers sort themselves into self-selected groups based on a variety of factors, such as specific interests. These interests could include types of restaurants or experiences they enjoy. They do not conform to being sorted according to the traditional demographic divisions.

- Using a common language when talking with your consumers ensures greater success and understanding of what products to build and marketing messages to launch.

- Laddering is a continual learning process that helps you establish relationships with your consumers in a new way.

- The individual has more power to influence than in any other period in modern history, and the time to start laddering your consumers for greater understanding is now.

Figure 2.2 Customers Clustered around the Motivations of Need to Be Connected and Willingness to Troubleshoot