CHAPTER 1

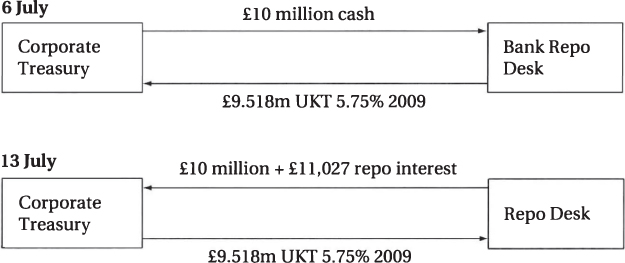

A Primer on Banking, Finance and Financial Instruments

“People still crave explanations even when there is no underlying understanding about what's going on…erratic stock market movements always find a ready explanation in the next day's financial columns: a price rise is attributed to sentiment that ‘pessimism about interest rate increases was exaggerated,’ or to the view that ‘company X had been oversold.’ Of course these explanations are always a posteriori: commentators could offer an equally ready explanation if a stock price had moved the other way.”

—Professor Martin Rees, Our Cosmic Habitat, Phoenix 2003, page 101

This chapter is reference material for newcomers to the market, junior bankers and finance students, or for those that require a refresher course on the core subject matter. The purpose of this primer is to introduce all the essential basics of banking, which is necessary if one is to gain a strategic overview of what banks do, what risk exposures they face and how to manage them properly. We begin with the concept of banking, and follow this with a description of bank cash flows, calculation of return, the risks faced in banking, and organisation and strategy.

Banking is a subset of “finance”. The principles of finance underlay the principles of banking. It would be difficult to become conversant with the principles of banking, and thus be in a position to manage a bank efficiently and effectively to the benefit of all stakeholders, unless one was also familiar with the principles of finance. That said, it is not uncommon to encounter senior executives and non‐executive directors on bank Boards who are perhaps not as au fait with basic principles as they should be. Hence, these basic principles are introduced here and remain the theme of Part I of this book.

AN INTRODUCTION TO BANKING

This extract from Bank Asset and Liability Management (2007)

Interest Rate Benchmarks

A transparent and readily accessible interest rate benchmark is a key ingredient in maintaining market efficiency. Countries that do not benefit from such a benchmark are markedly less liquid as a result.

Possibly the most well‐known interest rate benchmark is the London Interbank Offered Rate or Libor. It is calculated and published daily by ICE.

Wikipedia describes the Libor process as follows:

“The London Interbank Offered Rate is the average of interest rates estimated by a panel of leading banks in London on their expectation of what they would be charged were they to borrow from other banks. It is usually abbreviated to Libor or LIBOR, or more officially to ICE LIBOR (for Intercontinental Exchange Libor). It was formerly known as BBA Libor (for British Bankers' Association Libor or the trademark bba libor) before the responsibility for the administration was transferred to ICE. It is the primary benchmark, along with the Euribor, for short‐term interest rates around the world. Libor rates are calculated for five currencies and seven borrowing periods ranging from overnight to one year and are published each business day by Thomson Reuters. Many financial institutions, mortgage lenders and credit card agencies set their own rates relative to it. At least $350 trillion in derivatives and other financial products are tied to Libor.”

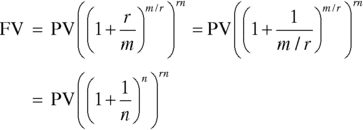

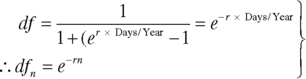

Figure 1.1 shows the Libor rates for 13 September 2016, as seen on the Bloomberg service, for USD, GBP and EUR. We note, for example, that GBP 3‐month Libor was 0.38%. Figure 1.2 shows the history for GBP 3‐month Libor from September 2011 to September 2016.

FIGURE 1.1 Libor screen on Bloomberg, 13 September 2016.

Source: © Bloomberg LP. Used with permission.

FIGURE 1.2 Libor history 2011–2016.

Source: © Bloomberg LP. Used with permission.

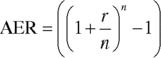

In developed markets, of course, there are usually a range of interest rate indicators. For example, depending on what instrument and market one is concerned with, the sovereign bond interest rates may be worth monitoring, or the overnight index swap (OIS) rate, and so on. It is important to be aware of rates relevant to the balance sheet risk management of your bank, and to understand as well as possible how they interact. Also important is some knowledge of the predictive power of yield curves and how to analyse and interpret them. For illustration, we show the GBP sovereign, interest rate swap, and overnight index swap (SONIA) yield curves for 13 September 2016 at Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.3 Sterling curves, 13 September 2016.

Source: © Bloomberg LP. Used with permission.

AN INTRODUCTION TO DEBT FINANCIAL MARKETS

In essence, banks deal in the business of debt, either deposits from customers (banks borrowing from customers), or loans to customers (banks lending to customers). They all “clear” at the end of the day with each other or directly with the central bank.1 Therefore we introduce the debt money markets and debt capital markets in this first chapter.

This extract from The Money Markets Handbook (2004)

The Money Markets

The Money Markets

Part of the global debt capital markets, the money markets are a separate market in their own right. Money market securities are defined as debt instruments with an original maturity of less than one year, although it is common to find that the maturity profile of banks' money market desks runs out to two years.

Money markets exist in every market economy, which is practically every country in the world. They are often the first element of a developing capital market. In every case they are comprised of securities with maturities of up to twelve months. Money market debt is an important part of the global capital markets, and facilitates the smooth running of the banking industry as well as providing working capital for industrial and commercial corporate institutions. The market provides users with a wide range of opportunities and funding possibilities, and the market is characterised by the diverse range of products that can be traded within it. Money market instruments allow issuers, including financial organisations and corporates, to raise funds for short term periods at relatively low interest rates. These issuers include sovereign governments, who issuer Treasury bills, corporates issuing commercial paper and banks issuing bills and certificates of deposit. At the same time investors are attracted to the market because the instruments are highly liquid and carry relatively low credit risk. The Treasury bill market in any country is that country's lowest‐risk instrument, and consequently carries the lowest yield of any debt instrument. Indeed the first market that develops in any country is usually the Treasury bill market. Investors in the money market include banks, local authorities, corporations, money market investment funds and mutual funds and individuals.

In addition to cash instruments, the money markets also consist of a wide range of exchange‐traded and over‐the‐counter off‐balance sheet derivative instruments. These instruments are used mainly to establish future borrowing and lending rates, and to hedge or change existing interest rate exposure. This activity is carried out by both banks, central banks and corporates. The main derivatives are short‐term interest rate futures, forward rate agreements, and short‐dated interest rate swaps such as overnight‐index seaps.

In this chapter we review the cash instruments traded in the money market. In further chapters we review banking asset and liability management, and the market in repurchase agreements. Finally we consider the market in money market derivative instruments including interest‐rate futures and forward‐rate agreements.

Introduction

The cash instruments traded in money markets include the following:

- Time deposits;

- Treasury Bills;

- Certificates of Deposit;

- Commercial Paper;

- Bankers Acceptances;

- Bills of exchange.

In addition money market desks may also trade repo and take part in stock borrowing and lending activities. These products are covered in a separate chapter.

Treasury bills are used by sovereign governments to raise short‐term funds, while certificates of deposit (CDs) are used by banks to raise finance. The other instruments are used by corporates and occasionally banks. Each instrument represents an obligation on the borrower to repay the amount borrowed on the maturity date together with interest if this applies. The instruments above fall into one of two main classes of money market securities: those quoted on a yield basis and those quoted on a discount basis. These two terms are discussed below. A repurchase agreement or “repo” is also a money market instrument and is considered in a separate chapter.

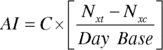

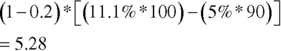

The calculation of interest in the money markets often differs from the calculation of accrued interest in the corresponding bond market. Generally the day‐count convention in the money market is the exact number of days that the instrument is held over the number of days in the year. In the UK sterling market the year base is 365 days, so the interest calculation for sterling money market instruments is given by (1.1):

However the majority of currencies including the US dollar and the euro calculate interest on a 360‐day base so the denominator in (1.1) would be changed accordingly. The process by which an interest rate quoted on one basis is converted to one quoted on the other basis is shown in Appendix 1.1. Those markets that calculate interest based on a 365‐day year are also listed at Appendix 1.1.

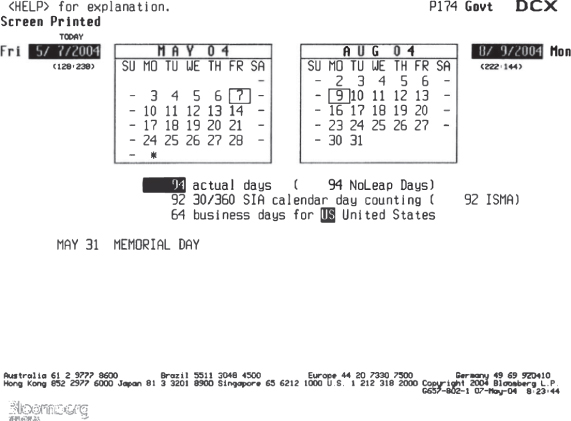

Dealers will want to know the interest day‐base for a currency before dealing in it as FX or money markets. Bloomberg users can use screen DCX to look up the number of days of an interest period. For instance, Figure 1.1 shows screen DCX for the US dollar market, for a loan taken out value 7 May 2004 for a straight three‐month period. Ordinarily this would mature on 7 August 2004, however from Figure 1.1 we see that this is not a good day so the loan will actually mature on 9 August 2004. Also from Figure 1.1 we see that this period is actually 94 days, and 92 days under the 30/360 day convention (a bond market accrued interest convention). The number of business days is 64, we also see that there is a public holiday on the 31 May.

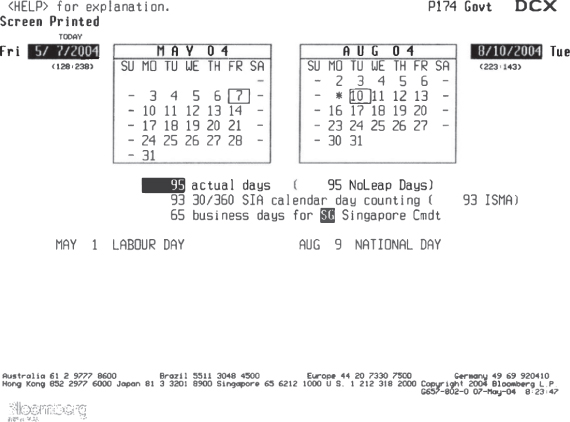

For the same loan taken out in Singapore dollars, look at Figure 1.2. This shows that the same loan taken out for value on 7 May will actually mature on 10 August, because 9 August 2004 is a public holiday in that market.

Figure 1.1 Bloomberg screen DCX used for US dollar market, three‐month loan taken out 7 May 2004

© Bloomberg L.P. Used with permission

Figure 1.2 Bloomberg screen DCX for Singapore dollar market, three‐month loan taken out 7 May 2004

© Bloomberg L.P. Used with permission

Settlement of money market instruments can be for value today (generally only when traded in before mid‐day), tomorrow or two days forward, known as spot.

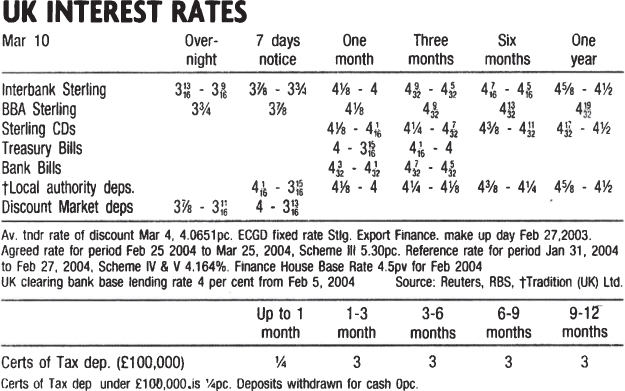

Figure 1.3 London sterling money market rates. Extract from Financial Times, 11 March 2004.

© Financial Times 2004. Reproduced with permission.

Securities quoted on a yield basis

Two of the instruments in the list above are yield‐based instruments.

Money market deposits

These are fixed‐interest term deposits of up to one year with banks and securities houses. They are also known as time deposits or clean deposits. They are not negotiable so cannot be liquidated before maturity. The interest rate on the deposit is fixed for the term and related to the London Interbank Offer Rate (LIBOR) of the same term. Interest and capital are paid on maturity.

Certificates of Deposit

Certificates of Deposit (CDs) are receipts from banks for deposits that have been placed with them. They were first introduced in the US dollar market in 1964, and in the sterling market in 1958. The deposits themselves carry a fixed rate of interest related to LIBOR and have a fixed term to maturity, so cannot be withdrawn before maturity. However the certificates themselves can be traded in a secondary market, that is, they are negotiable.1 CDs are therefore very similar to negotiable money market deposits, although the yields are about 0.15% below the equivalent deposit rates because of the added benefit of liquidity. Most CDs issued are of between one and three months' maturity, although they do trade in maturities of one to five years. Interest is paid on maturity except for CDs lasting longer than one year, where interest is paid annually or occasionally, semi‐annually.

Banks, merchant banks and building societies issue CDs to raise funds to finance their business activities. A CD will have a stated interest rate and fixed maturity date and can be issued in any denomination. On issue a CD is sold for face value, so the settlement proceeds of a CD on issue are always equal to its nominal value. The interest is paid, together with the face amount, on maturity. The interest rate is sometimes called the coupon,but unless the CD is held to maturity this will not equal the yield, which is of course the current rate available in the market and varies over time. The largest group of CD investors are banks, money market funds, corporates and local authority treasurers.

Unlike coupons on bonds, which are paid in rounded amounts, CD coupon is calculated to the exact day.

CD yields

The coupon quoted on a CD is a function of the credit quality of the issuing bank, and its expected liquidity level in the market, and of course the maturity of the CD, as this will be considered relative to the money market yield curve. As CDs are issued by banks as part of their short‐term funding and liquidity requirement, issue volumes are driven by the demand for bank loans and the availability of alternative sources of funds for bank customers. The credit quality of the issuing bank is the primary consideration however; in the sterling market the lowest yield is paid by “clearer” CDs, which are CDs issued by the clearing banks such as Royal Bank of Scotland, HSBC and Barclays Bank plc. In the US market “prime” CDs, issued by highly‐rated domestic banks, trade at a lower yield than non‐prime CDs. In both markets CDs issued by foreign banks such as French or Japanese banks will trade at higher yields.

Euro‐CDs, which are CDs issued in a different currency to that of the home currency, also trade at higher yields, in the US because of reserve and deposit insurance restrictions.

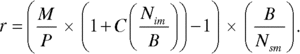

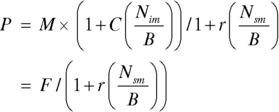

If the current market price of the CD including accrued interest is P and the current quoted yield is r, the yield can be calculated given the price, using (1.2):

The price can be calculated given the yield using (1.3):

Where

| C | is the quoted coupon on the CD |

| M | is the face value of the CD |

| B | is the year day‐basis (365 or 360) |

| F | is the maturity value of the CD |

| Nim | is the number of days between issue and maturity |

| Nsm | is the number of days between settlement and maturity |

| Nis | is the number of days between issue and settlement. |

After issue a CD can be traded in the secondary market. The secondary market in CDs in developed economies is very liquid, and CDs will trade at the rate prevalent at the time, which will invariably be different from the coupon rate on the CD at issue. When a CD is traded in the secondary market, the settlement proceeds will need to take into account interest that has accrued on the paper and the different rate at which the CD has now been dealt. The formula for calculating the settlement figure is given at (1.4) which applies to the sterling market and its 365‐day count basis.

The settlement figure for a new issue CD is of course, its face value…!2

The tenor of a CD is the life of the CD in days, while days remaining is the number of days left to maturity from the time of trade.

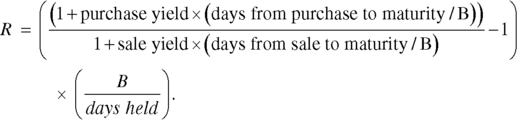

The return on holding a CD is given by (1.5):

Example 1.2

A three‐month CD is issued on 6 September 1999 and matures on 6 December 1999 (maturity of 91 days). It has a face value of £20,000,000 and a coupon of 5.45%. What are the total maturity proceeds?

What is the secondary market proceeds on 11 October if the yield for short 60‐day paper is 5.60%?

On 18 November the yield on short three‐week paper is 5.215%. What rate of return is earned from holding the CD for the 38 days from 11 October to 18 November?

US Dollar market rates

Treasury Bills

The Treasury bill market in the United States is the most liquid and transparent debt market in the world. Consequently the bid‐offer spread on them is very narrow. The Treasury issues bills at a weekly auction each Monday, made up of 91‐day and 182‐day bills. Every fourth week the Treasury also issues 52‐week bills as well. As a result there are large numbers of Treasury bills outstanding at any one time. The interest earned on Treasury bills is not liable to state and local income taxes. T‐bill rates are the lowest in the dollar market (as indeed any bill market is in respective domestic environment) and as such represents the corporate financier's risk‐free interest rate.

Federal Funds

Commercial banks in the US are required to keep reserves on deposit at the Federal Reserve. Banks with reserves in excess of required reserves can lend these funds to other banks, and these interbank loans are called federal funds or fed funds and are usually overnight loans. Through the fed funds market, commercial banks with excess funds are able to lend to banks that are short of reserves, thus facilitating liquidity. The transactions are very large denominations, and are lent at the fed funds rate, which is a very volatile interest rate because it fluctuates with market shortages.

Prime Rate

The prime interest rate in the US is often said to represent the rate at which commercial banks lend to their most creditworthy customers. In practice many loans are made at rates below the prime rate, so the prime rate is not the best rate at which highly rated firms may borrow. Nevertheless the prima rate is a benchmark indicator of the level of US money market rates, and is often used as a reference rate for floating‐rate instruments. As the market for bank loans is highly competitive, all commercial banks quote a single prime rate, and the rate for all banks changes simultaneously.

Securities quoted on a discount basis

The remaining money market instruments are all quoted on a discount basis, and so are known as “discount” instruments. This means that they are issued on a discount to face value, and are redeemed on maturity at face value. Treasury bills, bills of exchange, bankers acceptances and commercial paper are examples of money market securities that are quoted on a discount basis, that is, they are sold on the basis of a discount to par. The difference between the price paid at the time of purchase and the redemption value (par) is the interest earned by the holder of the paper. Explicit interest is not paid on discount instruments, rather interest is reflected implicitly in the difference between the discounted issue price and the par value received at maturity.

Treasury bills

Treasury bills or T‐bills are short‐term government “IOUs” of short duration, often three‐month maturity. For example if a bill is issued on 10 January it will mature on 10 April. Bills of one‐month and six‐month maturity are issued in certain markets, but only rarely by the UK Treasury. On maturity the holder of a T‐Bill receives the par value of the bill by presenting it to the Central Bank. In the UK most such bills are denominated in sterling but issues are also made in euros. In a capital market, T‐Bill yields are regarded as the risk‐free yield, as they represent the yield from short‐term government debt. In emerging markets they are often the most liquid instruments available for investors.

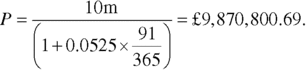

A sterling T‐bill with £10 million face value issued for 91 days will be redeemed on maturity at £10 million. If the three‐month yield at the time of issue is 5.25%, the price of the bill at issue is:

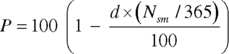

In the UK market the interest rate on discount instruments is quoted as a discount rate rather than a yield. This is the amount of discount expressed as an annualised percentage of the face value, and not as a percentage of the original amount paid. By definition the discount rate is always lower than the corresponding yield. If the discount rate on a bill is d, then the amount of discount is given by (1.12):

where B is the day‐count basis.

The price P paid for the bill is the face value minus the discount amount, given by (1.13):

If we know the yield on the bill then we can calculate its price at issue by using the simple present value formula, as shown at (1.14):

The discount rate d for T‐Bills is calculated using (1.15):

where n is the T‐bill number of days.

The relationship between discount rate and true yield is given by (1.16):

Example 1.4

A 91‐day £100 Treasury bill is issued with a yield of 4.75%. What is its issue price?

A UK T‐bill with a remaining maturity of 39 days is quoted at a discount of 4.95% What is the equivalent yield?

If a T‐Bill is traded in the secondary market, the settlement proceeds from the trade are calculated using (1.17):

Reproduced from The Money Markets Handbook (2004)

This extract from The Money Markets Handbook (2004)

Foreign Exchange Markets

Foreign Exchange Markets

The market in foreign exchange is an excellent example of a liquid, transparent and immediate global financial market. Rates in the foreign exchange (FX) markets move at an extremely rapid pace and in fact, trading in FX is a different discipline to bond trading or money markets trading. There is a considerable literature on the FX markets, as it is a separate subject in its own right. However some banks organise their forward FX desk as part of the money market desk and not the foreign exchange desk, necessitating its inclusion in this book. For this reason we present an overview summary of FX in this chapter, both spot and forward.

The quotation for currencies generally follows the ISO convention, which is also used by the SWIFT and Reuters dealing systems, and is the three‐letter code used to identify a currency, such as USD for US dollar and GBP for sterling. The rate convention is to quote everything in terms of one unit of the US dollar, so that the dollar and Swiss franc rate is quoted as USD/CHF, and is the number of Swiss francs to one US dollar. The exception is for sterling, which is quoted as GBP/USD and is the number of US dollars to the pound. This rate is also known as “cable”. The rate for euros has been quoted both ways round, for example EUR/USD although some banks, for example Royal Bank of Scotland in the UK, quote euros to the pound, that is GBP/EUR.

The complete list of currency codes was given at Appendix 1.2.

Spot exchange rates

A spot FX trade is an outright purchase or sale of one currency against another currency, with delivery two working days after the trade date. Non‐working days so not count, so a trade on a Friday is settled on the following Tuesday. There are some exceptions to this, for example trades of US dollar against Canadian dollar are settled the next working day; note that in some currencies, generally in the Middle‐East, markets are closed on Friday but open on Saturday. A settlement date that falls on a public holiday in the country of one of the two currencies is delayed for settlement by that day. An FX transaction is possible between any two currencies, however to reduce the number of quotes that need to be made the market generally quotes only against the US dollar or occasionally against sterling or euro, so that the exchange rate between two non‐dollar currencies is calculated from the rate for each currency against the dollar. The resulting exchange rate is known as the cross‐rate. Cross‐rates themselves are also traded between banks in addition to dollar‐based rates. This is usually because the relationship between two rates is closer than that of either against the dollar, for example the Swiss franc moves more closely in line with the euro than against the dollar, so in practice one observes that the dollar / Swiss franc rate is more a function of the euro / franc rate.

The spot FX quote is a two‐way bid‐offer price, just as in the bond and money markets, and indicates the rate at which a bank is prepared to buy the base currency against the variable currency; this is the “bid” for the variable currency, so is the lower rate. The other side of the quote is the rate at which the bank is prepared to sell the base currency against the variable currency. For example a quote of 1.6245 ‐ 1.6255 for GBP/USD means that the bank is prepared to buy sterling for $1.6245, and to sell sterling for $1.6255. The convention in the FX market is uniform across countries, unlike the money markets. Although the money market convention for bid‐offer quotes is for example, 5½% ‐ 5¼%, meaning that the “bid” for paper ‐ the rate at which the bank will lend funds, say in the CD market ‐ is the higher rate and always on the left, this convention is reversed in certain countries. In the FX markets the convention is always the same one just described.

The difference between the two side in a quote is the bank's dealing spread. Rates are quoted to 1/100th of a cent, known as a pip. In the quote above, the spread is 10 pips, however this amount is a function of the size of the quote number, so that the rate for USD/JPY at say, 110.10 ‐ 110.20, indicates a spread of 0.10 yen. Generally only the pips in the two rates are quoted, so that for example the quote above would be simply “45‐55”. The “big figure” is not quoted.

Example 2.1 Exchange cross‐rates

Consider the following two spot rates:

The EUR/USD dealer buys euros and sells dollars at 1.0566 (the left side), while the AUD/USD dealer sells Australian dollars and buys US dollars at 0.7039 (the right side). To calculate the rate at which the bank buys euros and sells Australian dollars, we need to do

which is the rate at which the bank buys euros and sells Australian dollars. In the same way the rate at which the bank sells euros and buys Australian dollars is given by

The derivation of cross‐rates can be depicted in the following way. If we assume two exchange rates XXX/YYY and XXX/ZZZ, the cross‐rates are:

Given two exchange rates YYY/XXX and XXX/ZZZ, the cross‐rates are:

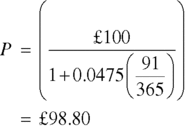

Figure 2.1 shows the Bloomberg major currency FX monitor, page FXC, as at 10 May 2004.

Figure 2.1 Bloomberg major currency monitor page, 10 May 2004

© Bloomberg L.P. Used with permission

Forward exchange rates

Forward outright

The spot exchange rate is the rate for immediate delivery (notwithstanding that actual delivery is two days forward). A forward contract or simply forward is an outright purchase or sale of one currency in exchange for another currency for settlement on a specified date at some point in the future. The exchange rate is quoted in the same way as the spot rate, with the bank buying the base currency on the bid side and selling it on the offered side. In some emerging markets no liquid forward market exists so forwards are settled in cash against the spot rate on the maturity date. These non‐deliverable forwards are considered at the end of this section.

Although some commentators have stated that the forward rate may be seen as the market's view of where the spot rate will be on the maturity date of the forward transaction, this is incorrect. A forward rate is calculated on the current interest rates of the two currencies involved, and the principle of no‐arbitrage pricing ensures that there is no profit to be gained from simultaneous (and opposite) dealing in spot and forward. Consider the following strategy:

- borrow US dollars for six months starting from the spot value date;

- sell dollars and buy sterling for value spot;

- deposit the long sterling position for six months from the spot value date;

- sell forward today the sterling principal and interest which mature in six months time into dollars.

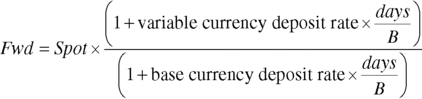

The market will adjust the forward price so that the two initial transactions if carried out simultaneously will generate a zero profit/loss. The forward rates quoted in the trade will be calculated on the six months deposit rates for dollars and sterling; in general the calculation of a forward rate is given as (2.1)

The year day‐count base B will be either 365 or 360 depending on the convention for the currency in question.

So in other words, a forward is more a deposit instrument than an FX instrument.

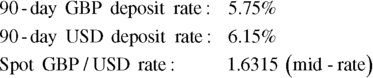

Example 2.2 Forward rate

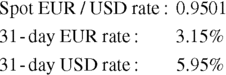

The forward rate is given by:

Therefore to deal forward the GBP/USD mid‐rate is 1.6296, so in effect £1 buys $1.6296 in three months time as opposed to $1.6315 today. Under different circumstances sterling may be worth more in the future than at the spot date.

Example 2.2 Forward rate arbitrage

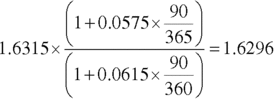

The following rates are quoted to a bank:

The bank requires funding of CHF10 million for three months (91 days). It deals on the above rates and actions the following:

- it borrows USD 6,749,915,63 for 91 days from spot at 7.56%

- at the end of the 91 days the bank repays the principal plus the interest, which is a total of USD 6,880,324.00

- the bank “buys and sells” USD against CHF at a swap price of 11, based on the spot rate of 1.4815, that is:

- the bank sells USD 6,749,915.63/buys CHF10 million spot at 1.4815;

- the bank buys USD 6,880,324/sells CHF 10,116,828.42 for three months forward at 1.4704;

The net USD cash flows result in a zero balance.

The effective cost of borrowing is therefore interest of CHF 116,828.41 on a principal sum of CHF10 million for 91 days, which is:

The net effect is therefore a CHF10 million borrowing at 4.57%, which is 5 basis points lower than the 4.62% quote at which the bank could borrow directly in the market. If the bank has not actually required funding but was able to deposit the Swiss francs at a higher rate than 4.57%, it would have been able to lock in a profit.

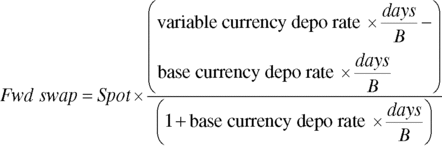

Forward swaps

The calculation given above illustrates how a forward rate is calculated and quoted in theory. In practice as spot rates change rapidly, often many times even in one minute, it would be tedious to keep re‐calculating the forward rate so often. Therefore banks quote a forward spread over the spot rate, which can then be added or subtracted to the spot rate as it changes. This spread is known as the swap points. An approximate value for the number of swap points is given by (2.2) below.

The approximation is not accurate enough for forwards maturing more than 30 days from now, in which case another equation must be used. This is given as (2.3). It is also possible to calculate an approximate deposit rate differential from the swap points by re‐arranging 2.2.

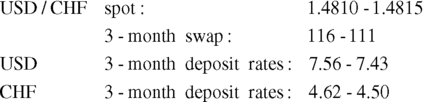

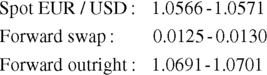

Example 2.3 Forward swap points

The forward outright is the spot price + the swap points, so in this case,

The swap points are quoted as two‐way prices in the same way as spot rates. In practice a middle spot price is used and then the forward swap spread around the spot quote. The difference between the interest rates of the two currencies will determine the magnitude of the swap points and whether they are added or subtracted from the spot rate. When the swap points are positive and the forwards trader applies a bid‐offer spread to quote a two‐way price, the left‐hand side of the quote is smaller than the right‐hand side as usual. When the swap points are negative, the trader must quote a “more negative” number on the left and a “more positive” number on the right‐hand side. The “minus” sign is not shown however, so that the left‐hand side may appear to be the larger number. Basically when the swap price appears larger on the right, it means that it is negative and must be subtracted from the spot rate and not added.

Forwards traders are in fact interest rate traders rather than foreign exchange traders; although they will be left with positions that arise from customer orders, in general they will manage their book based on their view of short‐term deposit rates in the currencies they are trading. In general a forward trader expecting the interest rate differential to move in favour of the base currency, for example, a rise in base currency rates or a fall in the variable currency rate, will “buy and sell” the base currency. This is equivalent to borrowing the base currency and depositing in the variable currency. The relationship between interest rates and forward swaps means that banks can take advantage of different opportunities in different markets. Assume that a bank requires funding in one currency but is able to borrow in another currency at a relatively cheaper rate. It may wish to borrow in the second currency and use a forward contract to convert the borrowing to the first currency. It will do this if the all‐in cost of borrowing is less than the cost of borrowing directly in the first currency.

Forward cross‐rates

A forward cross‐rate is calculated in the same way as spot cross‐rates. The formulas given for spot cross‐rates can be adapted to forward rates.

Forward‐forwards

A forward‐forward swap is a deal between two forward dates rather than from the spot date to a forward date; this is the same terminology and meaning as in the bond markets, where a forward or a forward‐forward interest rate is the zero‐coupon interest rate between two points both beginning in the future. In the foreign exchange market, an example would be a contract to sell sterling three months forward and buy it back in six months time. Here, the swap is for the three‐month period between the three‐month date and the six‐month date. The reason a bank or corporate might do this is to hedge a forward exposure or because of a particular view it has on forward rates, in effect deposit rates.

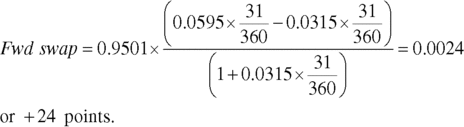

Example 2.4 Forward‐forward contract

If a bank wished to sell GBP three month forward and buy it back six months forward, this is identical to undertaking one swap to buy GBP spot and sell GBP three months forward, and another to sell GBP spot and buy it six months forward. Swaps are always quoted as the quoting bank buying the base currency forward on the bid side, and selling the base currency forward on the offered side; the counterparty bank can “buy and sell” GBP “spot against three months” at a swap price of −45, with settlement rates of spot and (spot − 0.0045). It can “sell and buy” GBP “spot against six months” at the swap price of −125 with settlement rates of spot and (spot − 0.0125). It can therefore do both simultaneously, which implies a difference between the two forward prices of (−125) − (−45) = −90 points. Conversely the bank can “buy and sell” GBP “three months against six months” at a swap price of (−135) − (−41) or −94 points. The two‐way price is therefore 94–90 (we ignore the negative signs).

Long‐dated forward contracts

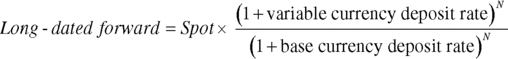

The formula for calculating a forward rate was given earlier (see 2.2). This formula applies to any period that is under one year, hence the adjustment of the deposit rate by the fraction of the day‐count. However if a forward contract is traded for a period greater than one year, the formula must be adjusted to account for the fact that deposit rates are compounded if they are in effect for more than one year. To calculate a long‐dated forward rate, in theory (2.4) should be used. In practice the formula may not give an answer to the required accuracy, because it does not consider reinvestment risk. To get around this it is necessary to use spot (zero‐coupon) rates in the formula. However the market in long‐dated forward contracts is not as liquid as the sub‐1‐year market, so banks may not be as keen to quote a price.

where N is the contract's maturity in years.

Reproduced from The Money Markets Handbook (2004)

This extract from Fixed Income Markets, Second Edition (2014)

The Bond Instrument

The Bond Instrument

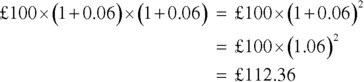

Bonds are debt‐capital market instruments that represent a cash flow payable during a specified time period heading into the future. This cash flow represents the interest payable on the loan and the loan redemption. So, essentially, a bond is a loan, albeit one that is tradable in a secondary market. This differentiates bond‐market securities from commercial bank loans.

In the analysis that follows, bonds are assumed to be default‐free, which means that there is no possibility that the interest payments and principal repayment will not be made. Such an assumption is reasonable when one is referring to government bonds such as U.S. Treasuries, UK gilts, Japanese JGBs, and so on. However, it is unreasonable when applied to bonds issued by corporates or lower‐rated sovereign borrowers. Nevertheless, it is still relevant to understand the valuation and analysis of bonds that are default‐free, as the pricing of bonds that carry default risk is based on the price of risk‐free securities. Essentially, the price investors charge borrowers that are not of risk‐free credit standing is the price of government securities plus some credit risk premium.

BOND MARKET BASICS

All bonds are described in terms of their issuer, maturity date, and coupon. For a default‐free conventional, or plain‐vanilla, bond, this will be the essential information required. Nonvanilla bonds are defined by further characteristics such as their interest basis, flexibilities in their maturity date, credit risk, and so on.

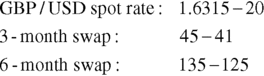

Figure 1.1 shows screen DES from the Bloomberg system. This page describes the key characteristics of a bond. From Figure 1.1, we see a description of a bond issued by the Singapore government, the 4.625% of 2010. This tells us the following bond characteristics:

| Issue date | July 2000 |

| Coupon | 4.625% |

| Maturity date | 1 July 2010 |

| Issue currency | Singapore dollars |

| Issue size | SGD 3.4 million |

| Credit rating | AAA/Aaa |

Figure 1.1 Bloomberg Screen DES Showing Details of 4⅝ % 2010 Issued by Republic of Singapore as of 20 October 2003

Used with permission of Bloomberg L.P. Copyright© 2014. All rights reserved.

Calling up screen DES for any bond, provided it is supported by Bloomberg, will provide us with its key details. Later on, we will see how nonvanilla bonds include special features that investors take into consideration in their analysis.

We will consider the essential characteristics of bonds later in this chapter. First, we review the capital market, and an essential principle of finance, the time value of money.

CAPITAL MARKET PARTICIPANTS

The debt capital markets exist because of the financing requirements of governments and corporates. The source of capital is varied, but the total supply of funds in a market is made up of personal or household savings, business savings, and increases in the overall money supply. Growth in the money supply is a function of the overall state of the economy, and interested readers may wish to consult the references at the end of this chapter, which include several standard economic texts. Individuals save out of their current income for future consumption, while business savings represent retained earnings. The entire savings stock represents the capital available in a market. The requirements of savers and borrowers differ significantly, in that savers have a short‐term investment horizon while borrowers prefer to take a longer‐term view. The constitutional weakness of what would otherwise be unintermediated financial markets led, from an early stage, to the development of financial intermediaries.

Financial Intermediaries

In its simplest form a financial intermediary is a broker or agent. Today we would classify the broker as someone who acts on behalf of the borrower or lender, buying or selling a bond as instructed. However, intermediaries originally acted between borrowers and lenders in placing funds as required. A broker would not simply on‐lend funds that have been placed with it, but would accept deposits and make loans as required by its customers. This resulted in the first banks. A retail bank deals mainly with the personal financial sector and small businesses, and in addition to loans and deposits also provides cash transmission services. A retail bank is required to maintain a minimum cash reserve, to meet potential withdrawals, but the remainder of its deposit base can be used to make loans. This does not mean that the total size of its loan book is restricted to what it has taken in deposits: loans can also be funded in the wholesale market. An investment bank will deal with governments, corporates, and institutional investors. Investment banks perform an agency role for their customers, and are the primary vehicle through which a corporate will borrow funds in the bond markets. This is part of the bank's corporate finance function; it will also act as wholesaler in the bond markets, a function known as market making. The bond‐issuing function of an investment bank, by which the bank will issue bonds on behalf of a customer and pass the funds raised to this customer, is known as origination. Investment banks will also carry out a range of other functions for institutional customers, including export finance, corporate advisory, and fund management.

Other financial intermediaries will trade not on behalf of clients but for their own book. These include arbitrageurs and speculators. Usually such market participants form part of investment banks.

Investors

There is a large variety of players in the bond markets, each trading some or all of the different instruments available to suit their own purposes. We can group the main types of investors according to the time horizon of their investment activity.

Short‐term institutional investors. These include banks and building societies, money‐market fund managers, central banks, and the treasury desks of some types of corporates. Such bodies are driven by short‐term investment views, often subject to close guidelines, and will be driven by the total return available on their investments. Banks will have an additional requirement to maintain liquidity, often in fulfilment of regulatory authority rules, by holding a proportion of their assets in the form of easily tradable short‐term instruments.

Long‐term institutional investors. Typically these types of investors include pension funds and life assurance companies. Their investment horizon is long term, reflecting the nature of their liabilities; often they will seek to match these liabilities by holding long‐dated bonds.

Mixed horizon institutional investors. This is possibly the largest category of investors and will include general insurance companies, most corporate bodies, and sovereign wealth funds. Like banks and financial‐sector companies, they are also very active in the primary market, issuing bonds to finance their operations.

Market professionals. This category includes the banks and specialist financial intermediaries mentioned earlier, firms that one would not automatically classify as “investors” although they will also have an investment objective. Their time horizon will range from one day to the very long term. Proprietary traders will actively position themselves in the market in order to gain trading profit, for example in response to their view on where they think interest rate levels are headed. These participants will trade directly with other market professionals and investors, or via brokers. Market makers or traders (called dealers in the United States) are wholesalers in the bond markets; they make two‐way prices in selected bonds. Firms will not necessarily be active market makers in all types of bonds; smaller firms often specialise in certain sectors. In a two‐way quote the bid price is the price at which the market maker will buy stock, so it is the price the investor will receive when selling stock. The offer price or ask price is the price at which investors can buy stock from the market maker. As one might expect, the bid price is always higher than the offer price, and it is this spread that represents the theoretical profit to the market maker. The bid‐offer spread set by the marketmaker is determined by several factors, including supply and demand, and liquidity considerations for that particular stock, the trader's view on market direction and volatility as well as that of the stock itself and the presence of any market intelligence. A large bid‐offer spread reflects low liquidity in the stock, as well as low demand.

Markets

Markets are that part of the financial system where capital market transactions, including the buying and selling of securities, takes place. A market can describe a traditional stock exchange; that is, a physical trading floor where securities trading occurs. Many financial instruments are traded over the telephone or electronically; these markets are known as over‐the‐counter (OTC) markets. A distinction is made between financial instruments of up to one year's maturity and instruments of over one year's maturity. Short‐term instruments make up the money market while all other instruments are deemed to be part of the capital market. There is also a distinction made between the primary market and the secondary market. A new issue of bonds made by an investment bank on behalf of its client is made in the primary market. Such an issue can be a public offer, in which anyone can apply to buy the bonds, or a private offer where the customers of the investment bank are offered the stock. The secondary market is the market in which existing bonds and shares are subsequently traded.

| Credit Rating | Maturity Range | Dealing Mechanism | Benchmark Bonds | Issuance | Coupon and Day‐Count Basis | |

| Australia | AAA | 2–15 years | OTC Dealer network | 5, 10 years | Auction | Semiannual, act/act |

| Canada | AAA | 2–30 years | OTC Dealer network | 3, 5, 10 years | Auction, subscription | Semiannual, act/act |

| France | AAA | BTAN: 1–7 years OAT: 10–30 years |

OTC Dealer network Bonds listed on Paris Stock Exchange |

BTAN: 2, 5 years OAT: 10, 30 years |

Dutch auction | BTAN: Semiannual, act/act OAT: Annual, act/act |

| Germany | AAA | OBL: 2, 5 years BUND: 10, 30 years |

OTC Dealer network Listed on Stock Exchange |

The most recent issue | Combination of Dutch auction and proportion of each issue allocated on fixed basis to institutions | Annual, act/act |

| South Africa | A | 2–30 years | OTC Dealer network Listed on Johannesburg SE |

2, 7, 10, 20 years | Auction | Semiannual, act/365 |

| Singapore | AAA | 2–15 years | OTC Dealer network | 1, 5, 10, 15 years | Auction | Semiannual, act/act |

| Taiwan | AA– | 2–30 years | OTC Dealer network | 2, 5, 10, 20, 30 years | Auction | Annual, act/act |

| United Kingdom | AAA | 2–50 years | OTC Dealer network | 5, 10, 30 years | Auction, subsequent issue by “tap” subscription | Semiannual, act/act |

| United States | AAA | 2–20 years | OTC Dealer network | 2, 5, 10 years | Auction | Semiannual, act/act |

Table 1.2 Selected Government Bond Markets, Yield Curves as at 2 December 2013

Source: Bloomberg LP.

| Term (years) | Australia | Germany | Japan | United Kingdom | United States |

| 1 | 0.43 | 0.110 | |||

| 2 | 2.74 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.250 |

| 3 | |||||

| 4 | |||||

| 5 | 3.49 | 0.66 | 0.18 | 1.58 | 1.251 |

| 7 | |||||

| 10 | 4.32 | 1.7 | 0.61 | 2.83 | 2.753 |

| 15 | 4.63 | 3.17 | |||

| 20 | 3.36 | ||||

| 30 | 2.62 | 1.65 | 3.64 | 3.756 |

BOND PRICING AND YIELD: THE TRADITIONAL APPROACH

Bond Pricing

The interest rate that is used to discount a bond's cash flows (and therefore called the discount rate) is the rate required by the bondholder. This is therefore known as the bond's yield. The yield on the bond will be determined by the market and is the price demanded by investors for buying it, which is why it is sometimes called the bond's return. The required yield for any bond will depend on a number of political and economic factors, including what yield is being earned by other bonds of the same class. Yield is always quoted as an annualised interest rate, so that for a bond paying semiannually exactly half of the annual rate is used to discount the cash flows.

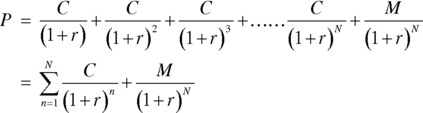

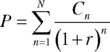

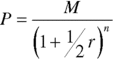

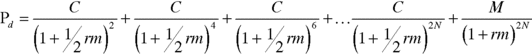

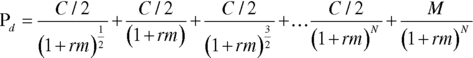

The fair price of a bond is the present value of all its cash flows. Therefore, when pricing a bond, we need to calculate the present value of all the coupon interest payments and the present value of the redemption payment, and sum these. The price of a conventional bond that pays annual coupons can therefore be given by (1.11).

| Where | P | is the price |

| C | is the annual coupon payment | |

| r | is the discount rate (therefore, the required yield) | |

| N | is the number of years to maturity (therefore, the number of interest periods in an annually paying bond) | |

| M | is the maturity payment or par value (usually 100% of currency) |

Note that (1.11) applies only for fixed coupon bonds where the “recovery rate” (RR) on default of the issuer is zero. In other words, we can only assume it for default‐risk free bonds. The RR term will be explained and considered in later chapters.

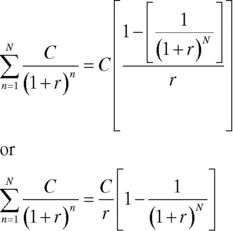

For long‐hand calculation purposes, the first half of (1.11) is usually simplified and is sometimes encountered in one of the two ways shown in (1.12).

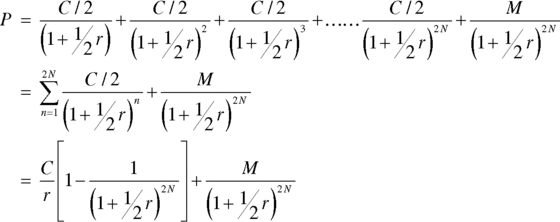

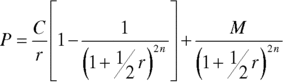

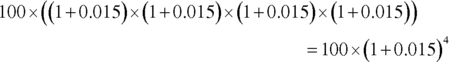

The price of a bond that pays semiannual coupons is given by the expression in (1.13), which is our earlier expression modified to allow for the twice‐yearly discounting:

Note how we set 2N as the power to which to raise the discount factor, as there are two interest payments every year for a bond that pays semiannually. Therefore, a more convenient function to use might be the number of interest periods in the life of the bond, as opposed to the number of years to maturity, which we could set as n, allowing us to alter the equation for a semiannually paying bond as:

The formula in (1.14) calculates the fair price on a coupon‐payment date, so that there is no accrued interest incorporated into the price. It also assumes that there is an even number of coupon‐payment dates remaining before maturity. The concept of accrued interest is an accounting convention, and treats coupon interest as accruing every day that the bond is held; this amount is added to the discounted present value of the bond (the clean price) to obtain the market value of the bond, known as the dirty price.

The date used as the point for calculation is the settlement date for the bond, the date on which a bond will change hands after it is traded. For a new issue of bonds, the settlement date is the day when the stock is delivered to investors and payment is received by the bond issuer. The settlement date for a bond traded in the secondary market is the day when the buyer transfers payment to the seller of the bond and when the seller transfers the bond to the buyer. Different markets will have different settlement conventions. For example, Australian government bonds normally settle two business days after the trade date (the notation used in bond markets is “T + 2”), whereas Eurobonds settle on T + 3. The term value date is sometimes used in place of settlement date. However, the two terms are not strictly synonymous. A settlement date can only fall on a business date, so that an Australian government bond traded on a Friday will settle on a Tuesday. However, a value date can sometimes fall on a non‐business day; for example, when accrued interest is being calculated.

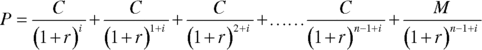

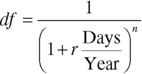

The standard formula also assumes that the bond is traded for a settlement on a day that is precisely one interest period before the next coupon payment. The price formula is adjusted if dealing takes place in between coupon dates. If we take the value date for any transaction, we then need to calculate the number of calendar days from this day to the next coupon date. We then use the following ratio i when adjusting the exponent for the discount factor:

The number of days in the interest period is the number of calendar days between the last coupon date and the next one, and it will depend on the day‐count basis used for that specific bond. The price formula is then modified as shown in (1.15).

where the variables C, M, n and r are as before. Note that (1.15) assumes r for an annually paying bond and is adjusted to r/2 for a semiannually paying bond.

Example 1.1

In these examples we illustrate the long‐hand price calculation, using both expressions for the calculation of the present value of the annuity stream of a bond's cash flows.

1.1 (A)

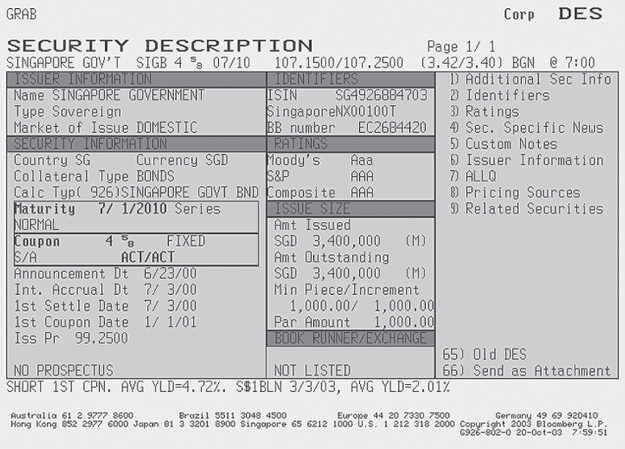

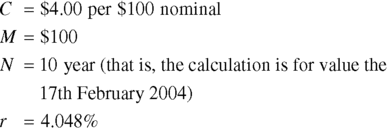

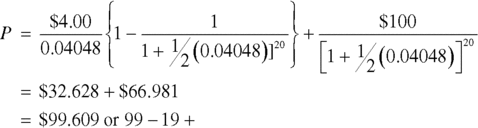

Calculate the fair pricing of a U.S. Treasury, the 4% of February 2014, which pays semiannual coupons, with the following terms:

The fair price of the Treasury is $99 − 19+, which is composed of the present value of the stream of coupon payments ($32.628) and the present value of the return of the principal ($66.981).

This yield calculation is shown at Figure 1.3, the Bloomberg YA page for this security. We show the price shown as 99 − 19+ for settlement on 17 Feb 2004, the date it was issued.

Figure 1.3 Bloomberg YA Page for Yield Analysis

Used with permission of Bloomberg L.P. Copyright© 2014. All rights reserved.

1.1(B)

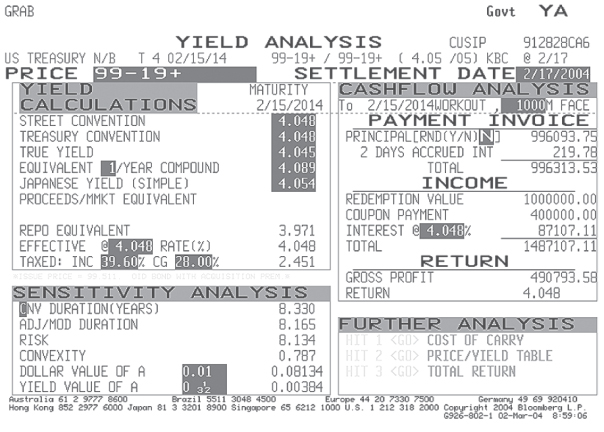

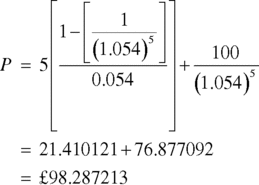

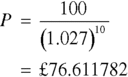

What is the price of a 5% coupon sterling bond with precisely five years to maturity, with semiannual coupon payments, if the yield required is 5.40%?

As the cash flows for this bond are 10 semiannual coupons of £2.50 and a redemption payment of £100 in 10 six‐month periods from now, the price of the bond can be obtained by solving the following expression, where we substitute C = 2.5, n = 10, and r = 0.027 into the price equation (the values for C and r reflect the adjustments necessary for a semiannual paying bond).

The price of the bond is $98.2675 per $100 nominal.

1.1(C)

What is the price of a 5% coupon euro bond with five years to maturity paying annual coupons, again with a required yield of 5.4%?

In this case there are five periods of interest, so we may set C = 5, n = 5, with r = 0.05.

Note how the annual‐paying bond has a slightly higher price for the same required annualised yield. This is because the semiannual paying sterling bond has a higher effective yield than the euro bond, resulting in a lower price.

1.1(D)

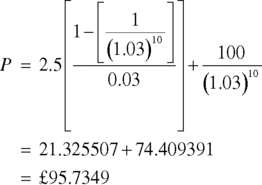

Consider our 5% sterling bond again, but this time the required yield has risen and is now 6%. This makes C = 2.5, n = 10, and r = 0.03.

As the required yield has risen, the discount rate used in the price calculation is now higher, and the result of the higher discount is a lower present value (price).

1.1(E)

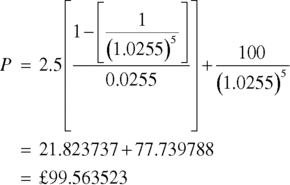

Calculate the price of our sterling bond, still with five years to maturity but offering a yield of 5.1%.

To satisfy the lower required yield of 5.1%, the price of the bond has fallen to £99.56 per £100.

1.1(F)

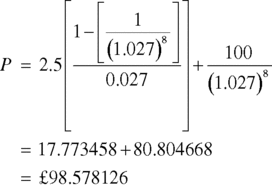

Calculate the price of the 5% sterling bond one year later, with precisely four years left to maturity and with the required yield still at the original 5.40%. This sets the terms in 1.1(b) unchanged, except now n = 8.

The price of the bond is £98.58. Compared to 1.1(B) this illustrates how, other things being equal, the price of a bond will approach par (£100 percent) as it approaches maturity.

There also exist perpetual or irredeemable bonds which have no redemption date, so that interest on them is paid indefinitely. They are also known as undated bonds. An example of an undated bond is the 3½% War Loan, a UK gilt originally issued in 1916 to help pay for the 1914–1918 war effort. Most undated bonds date from a long time in the past, and it is unusual to see them issued today. In structure, the cash flow from an undated bond can be viewed as a continuous annuity. The fair price of such a bond is given from (1.11) by setting N = ∞, such that:

In most markets, bond prices are quoted in decimals, in minimum increments of 1/100ths. This is the case with Eurobonds, euro‐denominated bonds, and gilts, for example. Certain markets—including the U.S. Treasury market and South African and Indian government bonds, for example—quote prices in ticks, where the minimum increment is 1/32nd. One tick is therefore equal to 0.03125. A U.S. Treasury might be priced at “98‐05” which means “98 and five ticks”. This is equal to 98 and 5/32nds which is 98.15625.

Bonds that do not pay a coupon during their life are known as zero‐coupon bonds or strips, and the price for these bonds is determined by modifying (1.11) to allow for the fact that C = 0. We know that the only cash flow is the maturity payment, so we may set the price as:

where M and r are as before and N is the number of years to maturity. The important factor is to allow for the same number of interest periods as coupon bonds of the same currency. That is, even though there are no actual coupons, we calculate prices and yields on the basis of a quasi‐coupon period. For a U.S. dollar or a sterling zero‐coupon bond, a five‐year zero coupon bond would be assumed to cover 10 quasi‐coupon periods, which would set the price equation as:

Example 1.2

What is the total consideration for £5 million nominal of a gilt, where the price is 114.50?

The price of the gilt is £114.50 per £100, so the consideration is:

What consideration is payable for $5 million nominal of a U.S. Treasury, quoted at an all‐in price of 99‐16?

The U.S. Treasury price is 99‐16, which is equal to 99 and 16/32, or 99.50 per $100. The consideration is therefore:

If the price of a bond is below par, the total consideration is below the nominal amount; whereas if it is priced above par, the consideration will be above the nominal amount.

Example 1.3

1.3(A)

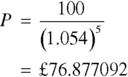

Calculate the price of a gilt strip with a maturity of precisely five years, where the required yield is 5.40%.

These terms allow us to set N = 5 so that n = 10, r = 0.054 (so that r/2 = 0.027), with M = 100 as usual.

1.3(B)

Calculate the price of a French government zero‐coupon bond with precisely five years to maturity, with the same required yield of 5.40%.

We have to note carefully the quasi‐coupon periods in order to maintain consistency with conventional bond pricing.

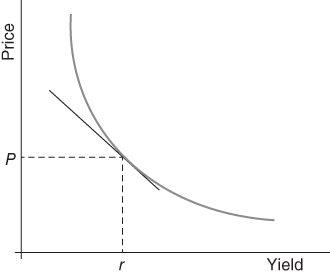

An examination of the bond price formula tells us that the yield and price for a bond are related. A key aspect of this relationship is that the price changes in the opposite direction to the yield. This is because the price of the bond is the net present value of its cash flows; if the discount rate used in the present value calculation increases, the present values of the cash flows will decrease. This occurs whenever the yield level required by bondholders increases. In the same way, if the required yield decreases, the price of the bond will rise. This property was observed in Example 1.2. As the required yield decreased, the price of the bond increased, and we observed the same relationship when the required yield was raised.

The relationship between any bond's price and yield at any required yield level is illustrated in a stylised manner in Figure 1.4, which is obtained if we plot the yield against the corresponding price; this shows a convex curve. In practice the curve is not quite as perfectly convex as illustrated in Figure 1.4, but the diagram is representative.

Figure 1.4 The Price/Yield Relationship

SUMMARY OF THE PRICE/YIELD RELATIONSHIP

At issue, if a bond is priced at par, its coupon will equal the yield that the market requires from the bond.

If the required yield rises above the coupon rate, the bond price will decrease.

If the required yield goes below the coupon rate, the bond price will increase.

BOND YIELD

We have observed how to calculate the price of a bond using an appropriate discount rate known as the bond's yield. We can reverse this procedure to find the yield of a bond where the price is known, which would be equivalent to calculating the bond's internal rate of return (IRR). The IRR calculation is taken to be a bond's yield to maturity or redemption yield and is one of various yield measures used in the markets to estimate the return generated from holding a bond. In most markets, bonds are generally traded on the basis of their prices, but because of the complicated patterns of cash flows that different bonds can have they are generally compared in terms of their yields. This means that a marketmaker will usually quote a two‐way price at which she will buy or sell a particular bond, but it is the yield at which the bond is trading that is important to the marketmaker's customer. This is because a bond's price does not actually tell us anything useful about what we are getting. Remember, that in any market there will be a number of bonds with different issuers, coupons, and terms to maturity. Even in a homogenous market such as the Treasury market, different bonds and notes will trade according to their own specific characteristics. To compare bonds in the market, therefore, we need the yield on any bond, and it is yields that we compare, not prices.

The yield on any investment is the interest rate that will make the present value of the cash flows from the investment equal to the initial cost (price) of the investment. Mathematically, the yield on any investment, represented by r, is the interest rate that satisfies (1.19), which is simply the bond price equation we've already reviewed.

But as we have noted there are other types of yield measure used in the market for different purposes. The simplest measure of the yield on a bond is the current yield, also known as the flat yield, interest yield or running yield. The running yield is given by (1.20).

where rc is the current yield.

In (1.20) C is not expressed as a decimal. Current yield ignores any capital gain or loss that might arise from holding and trading a bond and does not consider the time value of money. It essentially calculates the bond coupon income as a proportion of the price paid for the bond, and to be accurate would have to assume that the bond was more like an annuity rather than a fixed‐term instrument.

The current yield is useful as a rough‐and‐ready interest‐rate calculation; it is often used to estimate the cost of or profit from a short‐term holding of a bond. For example, if other short‐term interest rates such as the one‐week or three‐month rates are higher than the current yield, holding the bond is said to involve a running cost. This is also known as negative carry or negative funding. The term is used by bond traders and market makers and leveraged investors. The carry on a bond is a useful measure for all market practitioners as it illustrates the cost of holding or funding a bond. The funding rate is the bondholder's short‐term cost of funds. A private investor could also apply this to a short‐term holding of bonds.

The yield to maturity or gross redemption yield is the most frequently used measure of return from holding a bond.5 Yield to maturity (YTM) takes into account the pattern of coupon payments, the bond's term to maturity, and the capital gain (or loss) arising over the remaining life of the bond. We saw from our bond price formula in the previous section that these elements were all related and were important components determining a bond's price. If we set the IRR for a set of cash flows to be the rate that applies from a start‐date to an end‐date we can assume the IRR to be the YTM for those cash flows. The YTM therefore is equivalent to the internal rate of return on the bond, the rate that equates the value of the discounted cash flows on the bond to its current price. The calculation assumes that the bond is held until maturity, and therefore it is the cash flows to maturity that are discounted in the calculation. It also employs the concept of the time value of money.

As we would expect, the formula for YTM is essentially that for calculating the price of a bond. For a bond paying annual coupons, the YTM is calculated by solving (1.11). Note that the expression in (1.11) has two variable parameters, the price P and yield r. It cannot be rearranged to solve for yield r explicitly, and, in fact, the only way to solve for the yield is to use the process of numerical iteration. The process involves estimating a value for r and calculating the price associated with the estimated yield. If the calculated price is higher than the price of the bond at the time, the yield estimate is lower than the actual yield, and so it must be adjusted until it converges to the level that corresponds with the bond price.8 For the YTM of a semiannual coupon bond, we have to adjust the formula to allow for the semiannual payments, shown in (1.13).

Example 1.4 Yield to maturity for semiannual coupon bond

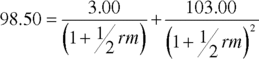

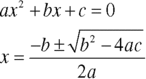

A semiannual paying bond has a dirty price of $98.50, an annual coupon of 6%, and there is exactly one year before maturity. The bond therefore has three remaining cash flows, comprising two coupon payments of $3 each and a redemption payment of $100. Equation 1.12 can be used with the following inputs:

Note that we use half of the YTM value rm because this is a semiannual paying bond. The preceding expression is a quadratic equation, which is solved using the standard solution for quadratic equations, which is noted in the following equations.

In our expression, if we let x = (1 + rm/2), we can rearrange the expression as follows:

We then solve for a standard quadratic equation, and there will be two solutions, only one of which gives a positive redemption yield. The positive solution is rm/2 = 0.037929 so that rm = 7.5859%.

As an example of the iterative solution method, suppose that we start with a trial value for rm of r1 = 7% and plug this into the right‐hand side of (1.12). This gives a value for the right‐hand side of:

which is higher than the left‐hand side (LHS = 98.50); the trial value for rm was therefore too low. Suppose then that we try next r2 = 8% and use this as the right‐hand side of the equation. This gives:

our linear approximation for the redemption yield is rm = 7.587%, which is near the exact solution.

To differentiate redemption yield from other yield and interest‐rate measures described in this book, we henceforth refer to it as rm.

Note that the redemption yield, as discussed earlier in this section, is the gross redemption yield, the yield that results from payment of coupons without deduction of any withholding tax. The net redemption yield is obtained by multiplying the coupon rate C by (1 − marginal tax rate). The net yield is what will be received if the bond is traded in a market where bonds pay coupon net, which means net of a withholding tax. The net redemption yield is always lower than the gross redemption yield.

We have already alluded to the key assumption behind the YTM calculation, namely that the rate rm remains stable for the entire period of the life of the bond. By assuming the same yield, we can say that all coupons are reinvested at the same yield rm. For the bond in Example 1.4, this means that if all the cash flows are discounted at 7.59% they will have a total net present value of 98.50. This is patently unrealistic since we can predict with virtual certainty that interest rates for instruments of similar maturity to the bond at each coupon date will not remain at this rate for the life of the bond. In practice, however, investors require a rate of return that is equivalent to the price that they are paying for a bond, and the redemption yield is, to put it simply, as good a measurement as any. A more accurate measurement might be to calculate present values of future cash flows using the discount rate that is equal to the forward interest rates at that point, known as the forward interest rate. However, forward rates are simply interest rates today for execution at a future date, and so a YTM measurement calculated using forward rates can be as speculative as one calculated using the conventional formula. So a YTM calculation made using forward rates would not be realised in practice either. We shall see later how the zero‐coupon interest rate is the true interest rate for any term to maturity. However, despite the limitations presented by its assumptions, the YTM is the main measure of return used in the markets.

We have noted the difference between calculating redemption yield on the basis of both annual and semiannual coupon bonds. Analysis of bonds that pay semiannual coupons incorporates semiannual discounting of semiannual coupon payments. This is appropriate for most UK and U.S. bonds. However, government bonds in most of continental Europe and most Eurobonds pay annual coupon payments, and the appropriate method of calculating the redemption yield is to use annual discounting. The two yields measures are not therefore directly comparable. We could make a Eurobond directly comparable with a UK gilt by using semiannual discounting of the Eurobond's annual coupon payments. Alternatively we could make the gilt comparable with the Eurobond by using annual discounting of its semiannual coupon payments. The price/yield formulae for different discounting possibilities we encounter in the markets are listed in the following equations (as usual we assume that the calculation takes place on a coupon payment date so that accrued interest is zero).

Semiannual discounting of annual payments:

Annual discounting of semiannual payments:

Consider a bond with a dirty price of 97.89, a coupon of 6%, and five years to maturity. This bond would have the following gross redemption yields under the different yield‐calculation conventions:

| Discounting | Payments | Yield to Maturity (%) |

| Semiannual | Semiannual | 6.500 |

| Annual | Annual | 6.508 |

| Semiannual | Annual | 6.428 |

| Annual | Semiannual | 6.605 |

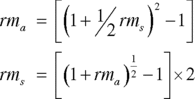

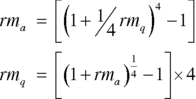

This proves what we have already observed: namely, that the coupon and discounting frequency will affect the redemption yield calculation for a bond. We can see that increasing the frequency of discounting will lower the yield, while increasing the frequency of payments will raise the yield. When comparing yields for bonds that trade in markets with different conventions, it is important to convert all the yields to the same calculation basis. Intuitively we might think that doubling a semiannual yield figure will give us the annualised equivalent; in fact, this will result in an inaccurate figure due to the multiplicative effects of discounting and one that is an underestimate of the true annualised yield. The correct procedure for producing an annualised yields from semiannual and quarterly yields is given by the following expressions.

The general conversion expression is given by (1.23):

where m is the number of coupon payments per year.

Specifically we can convert between yields using the expressions given in (1.24) and (1.25).

where rmq, rms, and rma are, respectively, the quarterly, semiannually, and annually compounded yields to maturity.

The market convention is sometimes simply to double the semiannual yield to obtain the annualised yields, despite the fact that this produces an inaccurate result. It is only acceptable to do this for rough calculations. An annualised yield obtained by multiplying the semiannual yield by two is known as a bond equivalent yield.

While YTM is the most commonly used measure of yield, it has one major disadvantage. The disadvantage is that implicit in the calculation of the YTM is the assumption that each coupon payment as it becomes due is reinvested at the rate rm.

Example 1.5

A UK gilt paying semiannual coupons and a maturity of 10 years has a quoted yield of 4.89%. A European government bond of similar maturity is quoted at a yield of 4.96%. Which bond has the higher effective yield?

The effective annual yield of the gilt is:

Therefore, the gilt does indeed have the lower yield.

This is clearly unlikely, due to the fluctuations in interest rates over time and as the bond approaches maturity. In practice, the measure itself will not equal the actual return from holding the bond, even if it is held to maturity. That said, the market standard is to quote bond returns as yields to maturity, bearing the key assumptions behind the calculation in mind.

Another disadvantage of this measure of return arises where investors do not hold bonds to maturity. The redemption yield measure will not be of great value where the bond is not being held to redemption. Investors might then be interested in other measures of return, which we can look at later.

To reiterate then, the redemption yield measure assumes that:

- The bond is held to maturity;

- All coupons during the bond's life are reinvested at the same (redemption yield) rate.

Therefore the YTM can be viewed as a prospective yield if the bond is purchased on issue and held to maturity. Even then the actual realised yield on maturity would be different from expected or anticipated yield and is closest to reality only where an investor buys a bond on first issue and holds the YTM figure because of the inapplicability of the second condition in the preceding list.

In addition, as coupons are discounted at the yield specific for each bond, it actually becomes inaccurate to compare bonds using this yield measure. For instance, the coupon cash flows that occur in two years time from both a two‐year and five‐year bond will be discounted at different rates (assuming we do not have a flat yield curve). This would occur because the YTM for a five‐year bond is invariably different from the YTM for a two‐year bond. However, it would clearly not be correct to discount a two‐year cash flow at different rates, because we can see that the present value calculated today of a cash flow in two years' time should be the same whether it is sourced from a short‐ or long‐dated bond. Even if the first condition noted earlier for the YTM calculation is satisfied, it is clearly unlikely for any but the shortest maturity bond that all coupons will be reinvested at the same rate. Market interest rates are in a state of constant flux and would thus affect money reinvestment rates. Therefore, although yield to maturity is the main market measure of bond levels, it is not a true interest rate. This is an important result, and we shall explore the concept of a true interest rate in Chapter 2.

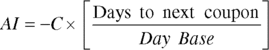

Accrued Interest, Clean and Dirty Bond Prices

Our discussion of bond pricing up to now has ignored coupon interest. All bonds accrue interest on a daily basis, and this is then paid out on the coupon date. The calculation of bond prices using present‐value analysis does not account for coupon interest or accrued interest. In all major bond markets, the convention is to quote price as a clean price. This is the price of the bond as given by the net present value of its cash flows, but excluding coupon interest that has accrued on the bond since the last dividend payment. As all bonds accrue interest on a daily basis, even if a bond is held for only one day, interest will have been earned by the bondholder. However, we have referred already to a bond's all‐in price, which is the price that is actually paid for the bond in the market. This is also known as the dirty price (or gross price), which is the clean price of a bond plus accrued interest. In other words, the accrued interest must be added to the quoted price to get the total consideration for the bond.

Accruing interest compensates the seller of the bond for giving up all of the next coupon payment even though she will have held the bond for part of the period since the last coupon payment. The clean price for a bond will move with changes in market interest rates; assuming that this is constant in a coupon period, the clean price will be constant for this period. However, the dirty price for the same bond will increase steadily from one interest payment date until the next. On the coupon date, the clean and dirty prices are the same and the accrued interest is zero. Between the coupon payment date and the next ex‐dividend date the bond is traded cum dividend, so that the buyer gets the next coupon payment. The seller is compensated for not receiving the next coupon payment by receiving accrued interest instead. This is positive and increases up to the next ex‐dividend date, at which point the dirty price falls by the present value of the amount of the coupon payment. The dirty price at this point is below the clean price, reflecting the fact that accrued interest is now negative. This is because after the ex‐dividend date the bond is traded “ex‐dividend”; the seller not the buyer receives the next coupon, and the buyer has to be compensated for not receiving the next coupon by means of a lower price for holding the bond.

The net interest accrued since the last ex‐dividend date is determined as follows:

| Where | AI | is the next accrued interest |

| C | is the bond coupon | |

| Nxc | is the number of days between the ex‐dividend date and the coupon payment date (seven business days for UK gilts) | |

| Nxt | is the number of days between the ex‐dividend date and the date for the calculation | |

| Day Base | is the day‐count base (365 or 360) |

Certain bonds do not have an ex‐dividend period (for example, Eurobonds) and accrue interest right up to the coupon date.

Interest accrues on a bond from and including the last coupon date up to and excluding what is called the value date. The value date is almost always the settlement date for the bond, or the date when a bond is passed to the buyer and the seller receives payment. Interest does not accrue on bonds whose issuer has subsequently gone into default. Bonds that trade without accrued interest are said to be trading flat or clean. By definition therefore,

For bonds that are trading ex‐dividend, the accrued coupon is negative and would be subtracted from the clean price. The calculation is given by (1.27).

As we noted, certain classes of bonds—for example, U.S. Treasuries and Eurobonds—do not have an ex‐dividend period and therefore trade cum dividend right up to the coupon date.