Chapter 12

The Challenge of Leadership Throughout the Organizational Life Cycle

One of the most critical managerial functions in promoting successful organizational development is leadership. Effective leadership is, in fact, a prerequisite for building sustainably successful organizations®. This is true, not only for leadership at the very top of the organization, but throughout it as well.

There are two different types of leadership that are required to build sustainably successful organizations®— strategic and operational. Strategic leadership is focused on building the organization over the longer term, while operational leadership is focused on execution or more day-to-day operations. During the early stages of a company's life cycle, these two types of leadership are typically, but not always, provided by the same person—the founder or CEO. As an organization grows and changes over its life cycle, the nature of the leadership it requires changes and becomes more complex. To meet the challenges, a company's leadership needs to evolve from a single leader to a “true leadership team,” or what we term a “leadership molecule”—described later in this chapter.

This purpose of this chapter is to identify and address the key leadership issues that companies face as they grow from early-stage entrepreneurship to larger, more complex organizations. We begin by clearly defining the concept of leadership, as well as the two types of leadership—strategic and operational—that need to be present in any organization at any size. Next, we identify six leadership styles and provide criteria that can be used to identify the “best” style for a specific situation. We then describe what we have termed the “key tasks” of operational and strategic leadership—that is, what effective leaders do. Building on the key tasks of strategic leadership, we introduce a concept we have termed the leadership molecule—a framework that can be used to assess the extent to which an organization's leadership team is focused on the most important factors that drive success and the extent to which they operate as a true team. In brief, this chapter focuses on the functions that need to be performed by leaders as their organizations grow and the form that leadership takes (i.e., whether these functions are performed by a single leader or by a leadership team). These issues are relatively neglected in the literature of leadership and organizational growth.

The Nature of Leadership

Although many people believe that leadership is an attribute of personality, this has not been confirmed by research, as we discuss later in this chapter. A more fruitful way to think about leadership is that it is a set of behaviors to be performed. In this sense, leadership is defined as “the process of influencing the behavior of people to achieve organizational goals.” Under this definition, leadership is an ongoing process, not a set of traits that a person possesses. The process involves understanding, predicting, and controlling others' goal-directed behavior. The leader's ultimate objective is to create a goal-congruent situation—a situation in which people can satisfy their own needs by seeking to achieve the goals of the organization. Leadership, then, like organizational control, is behaviorally-oriented and goal-directed.

There are two types of leadership: (1) operational leadership and (2) strategic leadership. Operational leadership is the process of influencing the behavior of people to achieve operational goals. This dimension of leadership is concerned with the day-to-day functioning of the enterprise. Strategic leadership, in contrast, is the process of influencing the organization's members to determine the future direction of the enterprise and its long-term objectives for organizational development. Both types of leadership are essential to building sustainably successful organizations®. Managers at all levels—CEO/COO, senior management, middle management, and front-line supervisors—need to be effective operational leaders. The most senior levels of the organization—the CEO/COO and his or her direct reports (as the organization grows)—need to also be effective strategic leaders. Effectively influencing people to achieve day-to-day and long-term goals involves choosing a style that fits the situation and performing key operational or strategic leadership tasks, as will be described below.

Styles of Leadership

There is a vast body of research and theory on leadership that can be summarized into various schools or classifications of leadership theory: (1) leadership trait theory, (2) leadership styles theory, and (3) contingency theories of leadership, which has also been termed situational leadership. More than half a century of research has failed to confirm that there is one “correct” style of leadership that is best for all situations—whether these are situations being encountered by the CEO, a middle manager, or a first-line supervisor. Rather, there are a variety of styles, each of which can be effective or ineffective, depending on the circumstances. This notion has been called contingency theory or situational leadership.

Based on our own and others' research, we have identified six basic styles of leadership. These styles constitute a continuum that proceeds from a very directive to a very nondirective leadership style, as summarized in Figure 12.1.

Figure 12.1 Continuum of Leadership Styles

It should be pointed out that this is only one of a variety of leadership classification schemes. The major point to draw from it is that in their purest form, these styles are indeed different and may therefore be appropriate for different situations with different personnel.

The Autocratic Style

The autocratic style is a very directive style of leadership. Someone using this style will make the decision or provide the direction typically without explaining the rationale behind it. This is the “just do it” style of leadership, which can best be characterized by the statement, “I will tell you what we're going to do because I'm the boss,” or “Look, I'm head of the department; I'm being held responsible. I will tell you what we're going to do, and that's that.” The spirit of autocratic leadership can also be captured in the exchange between a COO of a company and another high-ranking corporate leader in the presence of one of the authors: “When I say jump, you say,‘How high?’”

This was the style of leadership used by Sam Walton in the early years of his company and by Steve Jobs, during his early years at Apple and initially upon his 1997 return to the company. It is a style commonly observed in Fortune 500, as well as entrepreneurial organizations. For example, the legendary Jack Welch, the former CEO at GE, at one time was referred to as Neutron Jack because he was quick to make decisions about the firm and its subsidiaries in a very directive manner. However, Welch made the transition to using a much more participative style in his later years at GE.

The first reaction many people have to this style is negative. Why? Because beginning in the late twentieth century, managers were inundated with information suggesting that the way to achieve the “best” results was through maximizing the involvement of team members in decisions that will affect them. Although we agree with this, there are also times when managers must use a directive style in order to achieve the best results. For example, if a team is faced with a crisis, there may not be time to involve everyone in the decision. Someone must make it. Another example of a situation that may require a more directive style is when a manager is supervising an inexperienced or unmotivated employee. These types of employees require a more directive approach. In a sense, they want to be told what to do.

The Benevolent Autocratic Style

The benevolent-autocratic style is a “parental” style of leadership: The leader acts on the assumption that he or she knows what is best for the organization and the individuals involved. The degree of direction used in this style is essentially the same as with the autocratic style but is more benign. A manager who uses this style will usually explain the rationale behind decisions, whereas an autocratic leader will not. Instead of simply issuing directives, a person adopting this style might say, “I'll tell you what we're going to do, because it will be the best for all concerned.” Where an autocratic leader might say, “As a condition of coming to work here, you are obliged to accept what I say,” a benevolent autocrat might say, “This is what I want you to do, and here's why.” This is the classic style found in many entrepreneurships during the initial stages of organizational development.

The Consultative Style

The third style of leadership is qualitatively different, at least to some degree, from the first two. This is the first of two “interactive styles” in which the manager solicits input from direct reports but reserves the right to make the final decision. Managers using the consultative style (as opposed to the other interactive style, discussed next) tend to present their teams with information and ask for their response. To illustrate this, suppose a manager is presenting the organization's goals for the coming year. An individual operating with the autocratic style might say, “This is what we're going to do. These are our goals for next year.” A benevolent autocrat might approach the situation with, “This is what the organization needs, and here is how it will affect you.” In contrast, a manager using the consultative style might say, “Here is what I think our goals ought to be for the next year. What's your reaction?” Having asked this question, the manager then needs to make it very clear that while input is welcome, the decision is still his or hers to make. If this is not clear, problems can arise as direct reports come to believe that the manager was using a more nondirective style in which all votes were equal.

The Participative Style

A manager using the participative style also reserves the right to make the final decision. However, managers using this interactive style will tend to ask their teams for even greater input. The basic difference between the participative and consultative styles is the manner in which others' opinions are solicited and used. In the participative style, the group actually helps to develop ideas rather than just give input on the manager's ideas. In the consultative style, the manager might come into a group and say, “Here is what I think we should do. Give me your reaction.” The manager using a participative style, on the other hand, may have an idea about what the group should do but basically will say, “Here are the problems. Let's discuss them together and come up with recommendations. Then I'll make the final decision.”

There are certain challenges inherent in using either one of the interactive styles of leadership. First, a manager must be open to the ideas and opinions of his or her team and be willing to change perspective, based on these ideas. If the manager's mind is already made up, everyone on the team will know this and will be extremely frustrated by the fact that the manager is making them go through the motions of providing input, even though this input will not be used.

A second challenge is helping team members understand that, although the manager wants their input, the decision is still the manager's to make. This can be difficult to communicate, especially if none of the team's input is used. Whenever this occurs, the manager should make a practice of explaining a decision to pursue a certain course of action, how the information provided by the team was evaluated, and why (in this case) it wasn't used. This will help the team understand that their input was of value and that the manager wasn't simply creating the impression of soliciting input.

The Team (Consensus) Style

The team or consensus style represents another qualitative shift along the continuum of styles. It is the first of two nondirective styles in which the manager provides team members with a great deal of authority in the decision-making process. A leader adopting this style operates as a member of a team in making the decision. The leader's vote counts no more than any other team member's vote. A person using this leadership style might say, “Let's meet, discuss the problem, and reach an agreement on its resolution.” A group with a leader who uses this style is thus given more responsibility than in the other styles. This means that the leadership that is frequently exercised by a single individual under the more directive styles of leadership has been delegated as responsibility to a team of individuals.

There are two basic versions of the consensus style: (1) true consensus (or the jury) style and (2) majority rules. In the true consensus style, everyone on the team must agree on the direction to be pursued or the decision to be made. If there is even one dissenter, the “jury” must continue its deliberations until a true consensus is reached. This form of the consensus style obviously requires a great deal of time. More important, it requires that all team members be trained in how to use effective decision-making techniques. If team members do not understand the steps that should be followed in making effective decisions, they could meet forever and still not decide anything. Finally, it requires that team members leave their egos at the door. People need to be willing to agree to disagree and not feel that they've lost if a decision runs counter to their original opinion.

The second version of the consensus style is majority rules. A team using this style will literally vote on the course of action to pursue with respect to a particular issue. Whatever course of action the majority of participants selects (again, the team leader's vote counts no more than that of other team members) is the one that will be taken. When teams choose to use this version of the consensus style, they need to agree ahead of time how ties will be broken if they occur.

Although this version of the consensus leadership style tends to be less time consuming than the consensus version, it is not without problems. First, the majority-rules version of the consensus style creates winners and losers. This can significantly disrupt the ability of a team to work effectively together. Second, the losers can, if not properly managed, undermine the team's ability to effectively implement its decision. We have witnessed more than one case of senior managers who left the room after a majority-rules decision was made and told their direct reports, “That's the worst decision we ever made.”

The impact of such statements on the organization can be profound. First, the chances of the decision being implemented are reduced. Second, such statements can significantly undermine the image of the senior management team. The organization may come to believe that there is no true team directing the efforts of the company.

This is not to suggest that the consensus style should never be used. Instead, it is to point out that there are challenges in using this style (as there are in using any of the six key styles). These challenges need to be recognized and managed, if the style is to be used effectively. Although this is a complex style, an increasing number of organizations have been experimenting with it for a number of years.

The team style of leadership was used by Jim Stowers, Jr., at American Century Investments—a mutual fund, investment-management company—as he built the company from a new venture to one with more than $65 billion in assets. Stowers had long believed in the value of a team approach to portfolio management, and he extended this philosophy to the management of the company, where an increasing number of decisions were made by the firm's executive committee operating as a team. Stowers believed that teams make better decisions than individuals, and he wanted American Century's executive committee to function as a team CEO. Nevertheless, he reserved the right to use his extra vote to make certain decisions.

The Laissez-Faire Style

The most nondirective style of leadership—laissez-faire—places the responsibility for task accomplishment completely on the direct report. A leader using this style essentially says, “Do whatever you want to do,” or “Do the right thing.”

As was true of the autocratic style, some people's first reaction to this style is negative. Some even question whether such a style represents leadership at all. They ask, “How can a manager simply tell someone to ‘do what you want to do’?” The laissez-faire style, in fact, is quite a powerful style when used in the right situations. If a manager has someone who is highly skilled and highly motivated (that is, understands the requirements of the job and has the skills to effectively perform them), then the manager can just let this person “do it.” The manager does not need to devote a great deal of time to overseeing this individual's efforts. Instead, the manager's role becomes one of communicating the goals of the company to team members and letting them determine how the manager can best support them. The manager is still managing the team by ensuring that everyone is moving in a direction that will lead to the overall attainment of the company's goals. However, the amount of time that the manager needs to spend overseeing individual efforts is greatly reduced. The bottom line: If a manager can use a laissez-faire style in a given situation (if the circumstances are right), this will give him or her a great deal of time while also providing the desired results.

There are two versions of this style, one positive and one negative. A leader operating under the positive version promotes the notion that highly trained individuals do not need a great deal of direction. This type of leader thus gives his or her direct reports considerable independence. Such a leader might say, “You are a professional. You know what your job is. Do whatever you have to do to get it done.” This is the version of the style that we include in the continuum of styles presented in Figure 12.1.

The negative version of the laissez-faire style might be characterized by the statement, “Do whatever you want to do. Just leave me alone.” This is an “abdocratic” style—an abdication of authority and responsibility. This version of the laissez-faire style should never be used. It will do little to help a manager achieve desired results.

Factors Influencing the Choice of Leadership Style

It is important to understand that a manager at any level does not have to always use (and, in fact, shouldn't always use) the same leadership style. The most effective managers have the ability to use a variety of styles, each suited for a particular situation. Understanding the key factors that need to be considered in choosing an effective style to fit the situation helps managers increase their leadership effectiveness. We have found that consideration of six key factors can help an individual decide which style is best at a given time. The first two factors we discuss are the most important; they probably account for 80 to 90% of the influence on leadership effectiveness in a given situation.

Nature of the Task

One of the most important factors to consider in choosing a leadership style is the degree of programmability of the task on which the direct report will be working. A programmable task is one in which the manager can describe, in advance, all of the steps needed to complete it. A nonprogrammable task is a creative task in which it is almost impossible for a manager to define the steps necessary for its successful completion. If a task is highly programmable (that is, the optimal steps for its completion can be specified in advance), then a directive style of leadership is appropriate. If the task is nonprogrammable (that is, the nature of the work necessitates a great deal of variation in individual procedures), a directive style may be difficult or impossible to use, and a more participative or nondirective style will be required. In other words, the greater the degree of programmability of the task, the more appropriate it is for a manager to say, “This is the right way to do this task; we know it's right because we've studied it and worked out the best way to do it.” Where the task is less programmable, the manager must use a more interactive or nondirective approach.

Nature of the People Supervised

In identifying the “nature of the person,” a manager needs to consider three factors: (1) the level of skills the individual possesses; (2) how motivated the individual is; and (3) the extent to which the individual wants to work alone (that is, the extent to which he or she prefers to work on his or her own). When examining the nature of the situation, each of these factors should be assessed relative to the task that the individual direct report will be performing. For example, a person can be extremely skilled in one area and very motivated, but the task assigned requires a different set of skills. If a manager in this situation uses a nondirective approach, it can lead to a disaster because the person in question simply did not possess the required skills.

Taken together, these three factors comprise a single variable that we call the potential for job autonomy. The more highly skilled, highly motivated, and in need of independence a person is, the greater is that person's potential for job autonomy. Conversely, a person with low motivation, low task-relevant skills, and low need for independence has a low potential for job autonomy.

People with different potentials for job autonomy require managers with different leadership styles. A nondirective style (consensus or laissez-faire) will be most appropriate with direct reports who have a high potential for job autonomy, while a very directive style is appropriate with people who have low potential for job autonomy. A more intermediate style of leadership is needed when direct reports do not fit one or the other extreme.

As stated previously, these first two factors—nature of the task and nature of the person supervised—account for about 80 to 90% of what managers need to consider in choosing a leadership style. Figure 12.2 shows the relationship between the two factors we have just described and the six leadership styles described in the previous section.

Figure 12.2 Factors Affecting Choice of Leadership Style

As can be seen in the figure, a high degree of programmability combined with a low potential for job autonomy would ideally require a directive style. At the other extreme—low programmability and high job autonomy—a nondirective approach would be most effective. The other two cells show intermediate conditions where an interactive approach would best fit the situation. For example, a person who is highly motivated and working at a job that requires a high degree of nonprogrammability but is not very skilled may require a leader who adopts a style somewhere in the middle of the continuum, either consultative or participative, at least until the person becomes more experienced.

Supervisor's Style

If a difference exists between a supervisor's preferred leadership style and the style of one or more direct reports, it will be difficult for direct reports to justify their own style unless the supervisor allows the use of it. Direct reports may even feel a need to change their own style to make it closer to that of the supervisor. In other words, supervisors have a tendency to consciously or unconsciously evaluate their direct reports on the basis of their own leadership styles. The manager in the superior position in such a situation may need to recognize that people can use different styles and still be effective. Further, when an individual finds that the preferred style (given the evaluation of the first two factors described above) is different from the supervisor's dominant style, this person may need to find a way to help the supervisor understand why it is important that this style be used. The bottom line: If a manager uses the wrong style in a given situation, the probability that desired results will be achieved is reduced.

Peers' and Associates' Styles

The dominant style of a peer group can also influence a manager's choice of leadership style. For example, if most managers in a particular group use a consultative style and a few use a benevolent-autocratic style, the latter individuals will feel some pressure to change their style to make it more like that of the majority. Again, however, these individuals can work to educate their peers about the reasons behind their use of a different style and its influence on results. Further, if the individuals using the “non-dominant” leadership style begin to achieve superior results, concern about their style will be diminished.

Amount of Available Decision Time

People are much more willing to accept a directive leadership style in crisis situations than in situations where nothing needs to be decided in a hurry. If someone in a room full of people says, “I see smoke,” people will not expect to be asked to form groups and discuss alternatives for action. Most individuals will probably be quite comfortable with someone saying, “Stand up and calmly walk out the door, down the hall, and out into the street.”

Nature (Culture) of the Organization

Each organization has norms concerning the type or types of leadership style felt to be appropriate for its members. These norms affect all members of the organization and are likely to be influenced by the styles of the organization's founder, CEO, or most successful managers.

Leadership Style Is a Choice

The bottom line is that leadership style is a choice to be made. It is a style to be selected, based on the key factors in the situation. There are six key factors (described above) that affect the choice of leadership style. They can be analyzed to determine what kind of style would be most appropriate in a particular situation with particular types of personnel. Again, however, the most important of these factors are the first two.

Two Sets of Leadership Tasks

Two different types of leadership tasks must be performed in organizations. One of these can be termed the “micro” tasks—the tasks of operational leadership, which include all of the day-to-day things that must be performed to influence people to produce and deliver the products and services that the organization offers to the marketplace. The other set is the “macro” tasks of leadership. These tasks comprise what we call strategic leadership and include establishing the organization's vision, managing the corporate culture, managing the strategic aspects of the company's operations, developing the systems needed to support the long-term development of the business, and managing change.

Key Tasks of Operational Leadership

Operational leadership tasks are the things that a manager (at any level of the organizational hierarchy) needs to do on a day-to-day basis to influence the behavior of people to achieve goals. Previous research has identified five tasks that comprise the functions of operational leadership.1 To be effective as operational leaders, managers must perform all five key tasks on a regular basis with each of their direct reports. If any task is not focused on to the extent that it needs to be, the likelihood that desired results will be achieved decreases.

Goal Emphasis. An effective leader emphasizes the attainment of goals through setting goals, focusing on goals, ensuring the effective communication of goals, and monitoring performance against goals. The late Rensis Likert, an internationally noted behavioral scientist, pointed out that to be effective, a leader has to demonstrate a “contagious enthusiasm for the achievement of organizational goals.” To be an effective leader, then, an individual needs to understand how to set effective goals and ensure that those responsible for helping achieve them understand them. The concept of effective goal setting was discussed in both Chapter 6 and Chapter 8.

In performing this task, the effective leader's style can vary widely. A very directive or autocratic leader might simply say, “Here are our goals.” At the other extreme, a very nondirective or laissez-faire leader might say, “Let's agree on what our goals are, then you figure out how to achieve them.” At the intermediate level, a person with a participative or consultative style might say, “Here's what I think our goals should be. What do you think?”

One of our favorite examples of the succinct application of goal emphasis was observed in an executive committee meeting at a rapidly growing medical engineering subsidiary of Bristol-Myers Squibb. The company's CEO was asked how he might implement the concept of goal emphasis. He turned to the vice president of sales and stated simply, “Sell something!”

One of the best leaders we have encountered with respect to goal emphasis is Howard Schultz of Starbucks. In the best sense, Schultz is a demanding leader. He not only wants “guns and butter” but “entertainment” as well. Specifically, Schultz wants growth and profitability. At the same time, he wants people to have fun (a cultural goal). Although these things are sometimes at odds, Starbucks has done a very good job overall at all three. This has been accomplished, in part, because goals have been established to drive results in all three areas.

Interaction Facilitation. To achieve desired results, an effective leader needs to focus on helping people work together effectively and cooperatively. This is the definition of interaction facilitation. Effectively performing this task involves effective meeting management and team-building.

Individuals who effectively perform this task ensure that every meeting has a purpose and clear objectives that define what is supposed to be accomplished. They understand that there should be agendas for all meetings (distributed in advance) and that all participants should be prepared for whatever discussion will be taking place during the meeting. These individuals also understand how to manage meetings in a way that desired results are achieved (for example, decisions are made, action steps are developed, etc.). Someone using a directive leadership style might accomplish this task by saying, “We're having a meeting. This is our agenda, and this is what we're going to accomplish.” A more nondirective way to do the same thing might be to act as a facilitator at a meeting, helping to summarize what people are doing and asking nondirective questions.

Unfortunately, many CEOs and other executives sometimes dominate meetings, rather than facilitate the process. Either because of their personalities or because they assume it is their role, they tend to lead (direct) meetings. Where this has become dysfunctional, an outside facilitator can be of great help. The key is getting all issues and opinions on the table and then working to resolve them.

Work Facilitation. Performing this task involves providing or helping personnel obtain what they need to achieve their goals. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways, including helping to schedule a task, making suggestions about how work should be done, providing reference materials, and suggesting knowledgeable sources of information regarding task procedure. A very directive way of facilitating work might be to say, “This is the way you should be doing your job.” At the other extreme, a person using a laissez-faire style might simply ask nondirective questions or suggest that people look in certain areas for help.

Supportive Behavior. This fourth task of effective leadership involves providing both positive and negative feedback to direct reports on a regular basis. Positive feedback is important because it serves to reinforce appropriate goal-oriented behavior and thereby increase the chances that the behavior will continue to be performed. Negative feedback, in the form of constructive criticism, tends to eliminate dysfunctional behavior. Providing feedback effectively involves being as specific as possible, focusing on the individual's behavior (versus interpreting what the behavior means or focusing on the person's attitude), and adjusting one's style of communication to that of the person receiving the feedback. It also involves striking the right balance between providing feedback in a timely manner and doing so in the right place (e.g., constructive criticism should be provided one-on-one versus in a team setting).

A directive leader might express supportive behavior with “No, John. Don't do it that way. Do it this way.” A person using a more nondirective style might handle a similar situation with, “I'm going to have to evaluate what you do on this project. You do a self-assessment at the same time. Then, let's meet and compare notes, and we'll see where we need to go from there.” An extremely nondirective approach might be to say, “You've just completed the project. I want you to review your documentation and critique it. What have you done well? What have you done poorly, and how will you better this in the future?”

Personnel Development. The effective leader helps to develop people. He or she motivates people to be concerned about their future development—working with each direct report to analyze their specific needs for development and identifying ways to meet these needs. One way of performing this task that some managers have found effective is to work with each direct report to set at least one goal on an annual basis that relates to improving the person's skills and performance.

As was the case with the other factors, the leadership style used to perform this task can range from directive to nondirective, depending on the personnel and the nature of the work being done. A directive approach might be to say, “I think you should go to this management training program.” A nondirective approach might be to say, “What do you see as your developmental needs? I want you to think about them and to decide what you want to do to meet them.”

Key Tasks of Strategic Leadership

Strategic leadership tasks are the things that leaders do to plan for and manage the organization's long-term development. These tasks need to be focused upon and performed by the organization's most senior leaders on an ongoing basis. In the early stages of development, these five tasks will be performed by the entrepreneur or founder. As the organization grows, the leadership team will need to share responsibility for performing these tasks and do so as a “molecule” (which will be discussed later in this chapter). Each of the five strategic leadership tasks is described, in turn, below.

Strategic Vision. Formulating and effectively communicating a strategic vision is the first task of strategic leadership. This involves clearly defining what the organization will or should be working to achieve and then effectively communicating this “vision” throughout the business. In brief, it involves creating a picture of what the future state will be like. For example, Howard Schultz's original vision was to create an American version of the classic Italian coffee bar and roll it out on a national basis, even though Starbucks then had only two retail stores in Seattle.

Although the development of a vision is a requirement for effective strategic leadership, the content of the vision does not have to be created by the entrepreneur or CEO, per se. Many strategic leaders are effective because they create an environment or process through which the leadership team develops the vision for the firm. For example, in 1995 (as discussed in Chapter 6) the senior leadership team at Starbucks created the strategic mission for Starbucks which was, “To become the leading brand of specialty coffee in North America by the year 2000.” This strategic vision was intended to help Starbucks develop a niche or stronghold with sufficient strength to defend itself against competitors such as McDonald's or other large fast-food retailers with the financial resources to preempt Starbucks in the market. Once this was accomplished, Starbucks then proceeded to attempt to establish itself as a global brand with a global footprint.

Corporate Culture Management. The second task of strategic leadership concerns the management of the organization's culture. This task ultimately falls to the CEO of an entity, whether it is a corporation as a whole or a subdivision. Initially, the culture of a company is formulated and spread by the company's founder. However, when an organization reaches or exceeds a certain size (Stage IV), it must be formally managed, as explained in Chapter 3. At that point, a company needs to establish a formal system for culture management. For example, under Fuad El-Hibri's leadership at Emergent BioSolutions (a publicly traded biopharmaceutical company), the company began a formal system of culture management in 2009.2 This included creating a statement of the company's culture and establishing culture management as a priority objective in the company's strategic plan.

In addition to ensuring that there is an appropriate system for managing corporate culture, effectively performing this strategic leadership task involves serving as a role model of the company's desired culture. Promoting values needs to be a focus of leaders on an ongoing basis, versus something that is focused upon only when there is a need to change.

Operations. Ensuring that operations are aligned with and functioning effectively to help the organization achieve its long-term goals is the third task of strategic leadership. Operations refers to the day-to-day activities that take place in the business—that is, how systems and processes are actually implemented and how people behave within their roles. However, there is a strategic aspect of operations in addition to their day-to-day execution. The strategic aspect involves the development of processes and systems required for effective and efficient day-to-day functioning. This task of strategic leadership also involves the monitoring of operations to make sure that they are functioning as planned. This task is sometimes (but not always) the responsibility of a chief operating officer.

The strategic leadership task of operations is the same regardless of the specifics of retail, financial services, manufacturing, or other industries. It involves ensuring the effective execution of the strategic plan and ensuring the smooth functioning of day-to-day business activities, or what is sometimes referred to as “making the trains run on time.”

Organizational Development and Systems. The fourth key task of strategic leadership involves organizational development and related systems. In this context, the term organizational development refers to the whole process of influencing the members of the organization to build the various key aspects of the Pyramid of Organizational Development that have been described throughout this book.

As an organization grows and changes, it requires changes in its infrastructure. The strategic leadership organizational development/systems task involves focusing on designing and implementing the infrastructure (both operational and management systems) required by an organization as it grows. These are the systems required to support the organization's ongoing successful development versus day-to-day operations per se. For example, logistics and information systems are needed to support day-to-day operations of Walmart (and they need to be designed so that they are aligned with the company's long-term goals and are supported by other aspects of the company's infrastructure). They are implemented through day-to-day activities such as inventory counts, entering data, and truck deliveries.

This is not to suggest that effectively performing this task involves understanding all of the technical details of all organizational systems. Instead, effectively performing this task involves overseeing the development and implementation of key operational and management systems and doing so in a holistic manner. In performing this task, leaders will bring in technical experts, as needed, to assist with the details.

Innovation and Change Management. This strategic leadership task involves identifying the need for and managing organizational innovation and change. The overall goal of someone performing this task is to help ensure that change is an ongoing process (versus something that happens only periodically) and, in a sense, to champion change and innovation throughout the organization. The focus for innovation and change can be on any aspect of the company's operations—products, processes, people, systems, and so on. In a sense, this task can be viewed as the essence of entrepreneurship per se. For example, the development of the “i-technology” platform by Apple has facilitated its becoming one of the most valuable companies in the world.3

This task ultimately falls to the CEO of an entity, whether it is a corporation as a whole or a division. Change is inevitable in an organization as it grows or adapts to its environment.

Although the ultimate responsibility for managing change is the responsibility of the CEO, it is often managed as a group process by the senior leadership of an enterprise. This is a sound approach to the management of change that will be discussed below in the context of what we term a “leadership molecule.”

The Leadership Molecule

This section examines and develops the notion of a leadership molecule, cited above. It explains the role the molecule plays as companies pass through the various stages of organizational growth. It begins, in other words, to develop an alternative theory of leadership in organizations, which is termed “the leadership molecule hypothesis.” This hypothesis is the outgrowth, as we shall explain, of inductive observation of actual business practice. We also cite some empirical research that tested and supported the leadership molecule hypothesis. Finally, we shall examine the implications of this construct for the management of organizations as they grow through the organizational life cycle.

The Conventional Paradigm of Leadership

The conventional paradigm of business leadership is based upon the notion of a single leader such as Howard Schultz at Starbucks, Richard Branson at the Virgin Group, or the late Steve Jobs at Apple. Although such leaders do undoubtedly exist (especially during the early stages of entrepreneurial growth), they are often, like the tip of an iceberg, the most visible component of an unnoticed or unrecognized leadership unit.

Although it might appear that there is a single charismatic leader who determines the success of a company, if we look more closely, there is typically a core leadership team (in the true sociological sense) with defined but overlapping and complementary roles. Specifically, this team is actually performing the five key strategic leadership tasks, discussed above, as a collective unit rather than as a set of individuals. We refer to this true team of leaders as a “leadership molecule.”4 When we refer to a true leadership team, we do not mean a nominal team or a team in name only. Calling a group of people a “team” does not make them a team. We mean a team in the sense of relative equals in decision making, where rank and ego do not trump candid discussion of organizational issues, strategies, and problems. Such a team will have open debate, without hidden agendas, and challenge each other's assumptions and ideas, and it will think of itself as a team. Do such teams really exist? The answer is—occasionally.

We have observed such teams in business and have even helped some of them form. A great example, as discussed below, is the original senior leadership team at Starbucks in the early 1990s. Based on our research and experience in working with companies, we believe that as entrepreneurial organizations grow, they require a leadership molecule to perform the key functions of strategic leadership.

Accidental Discovery

Although most of the literature dealing with leadership focuses on the individual as a leader, there has been previous recognition of the notion that leadership can be exercised by a team or group rather than by an individual.5 However, the notion of a leadership molecule, as defined below, has not been generally recognized.

Like the identification of the antibiotic properties of penicillin, the existence of the notion of a leadership molecule was an accidental discovery. It occurred as a by-product of organizational development work with several companies over many years. Specifically, Eric Flamholtz observed that a common aspect of a number of highly successful companies was the existence of a “core leadership team” (in the true sociological sense of a “traditioned” group) with defined but overlapping and complementary roles.

The initial instance of recognition was at Starbucks Coffee. The core senior leadership team, as explained further below, was comprised of three leaders who worked as a team and possessed complementary skills and overlapping but semi-distinct roles.6

Performing the Key Strategic Leadership Tasks as a Team

This leadership team at Starbucks was performing the five key strategic leadership tasks as a collective unit rather than as a set of individuals. Each member of the core senior leadership team at Starbucks (Howard Schultz, Howard Behar, and Orin Smith) had his own defined formal role. Schultz was CEO, Behar was head of retail operations, and Smith was the CFO. The formal roles were somewhat of a misnomer and only partially reflected (and partially obscured) the actual or real roles of each of these three individuals. Each member of the team was, in fact, primarily (but not exclusively) responsible for a strategic leadership function. Howard Schultz (the CEO) was primarily (but not exclusively) responsible for the vision and culture of Starbucks. Schultz was also involved to some extent with operations and systems at Starbucks. Howard Behar, SVP and head of retail operations was primarily responsible for retail operations (which, at the time of this observation in 1994, accounted for approximately 95% of Starbucks' revenues). However, Behar was also involved to some extent with creating the vision and culture of Starbucks as well as its systems. Finally, Smith, who was formally CFO, was involved primarily with the development of the systems required by Starbucks—not just financial systems, but information systems, planning systems, human resource management systems, and other systems as well. However, he too was involved in creating the vision and culture of Starbucks and to some extent with operations as well. All three were involved with innovation and change at Starbucks.

Taken together, Schultz, Behar, and Smith were functioning not as a set of discrete individuals preforming independent roles; they were functioning as a true team (not just a team in name only) performing a set of complementary but somewhat overlapping roles. They comprised what we have termed a leadership molecule.

The Catalyst for the Leadership Molecule Construct

During early 1994, when Starbucks was still a relatively small company, Eric Flamholtz was invited to coach the three senior leaders of Starbucks, consisting of Howard Schultz, Howard Behar, and Orin Smith. His initial assignment was to coach each of them individually and to work with them to iron out some conflict and differences that had emerged in the stress of building a company so rapidly. After this initial work, they became a very effective leadership team. Flamholtz began to view them as an ideal senior leadership team: a set of very talented individuals with complementary capabilities, working as a true team.

The specific catalyst for the notion of the leadership molecule was the observation that people inside of Starbucks referred to them as “H2O.” This was a clever play on the initial letters of each individual's name: (H)oward Schultz, (H)oward Behar, and (O)rin Smith. Clearly people within Starbucks saw the three as a unit, and not just three guys running a company.

That moniker started Flamholtz thinking about other teams that he had observed in different companies: some with monikers such as “The Three Musketeers,” “The Troika,” The “Gang of Four,” “Batman and Robin,” and “The Ghost and the Darkness.”7 He realized that a nickname might be a “marker” or a signature for a true leadership team.

After the initial observation of this phenomenon, he began to investigate it more systematically. Based on an analysis of hundreds of companies, Flamholtz determined that where a “true team” existed, there was high performance and where it was lacking, performance tended to be low or even disastrous. This, in turn, led to what can be termed the Leadership Molecule Model and the Leadership Molecule Hypothesis.

Emergence and Development of a Leadership Molecule in Organizations

The leadership molecule tends to emerge as a function of the stage of development (growth) of a company. At the initial new venture stage, the leader is typically a one-man or -woman band that should be performing all of the required strategic leadership functions. This happens whether or not a single individual possesses all of the competencies to execute each of these leadership tasks.

As the organization grows, there is a need for managerial specialization and the development of a set of people to perform these functions rather than a single individual doing them all. Even when a single person possesses all of the capabilities to perform all of these leadership tasks, as an organization increases in size, it becomes more and more difficult to perform all functions.

As a result, a set of individuals tends to emerge to perform these tasks with one person typically focused on vision and culture, another on operations, a third on the development of systems, and the team as a whole working together to perform the task of change and innovation. If this set of individuals is not functioning as a team, then each person consists of an individual “atom.” Sometimes the set of individuals morphs into a true team with overlapping and complementary responsibilities. Only when the set of individual atoms has transformed into a true team or “molecule” does the so-called leadership molecule exist.

Core Roles of the Leadership Molecule

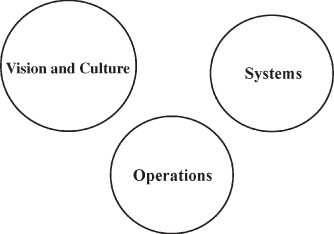

As implied above, there are certain core roles comprising the leadership molecule. These roles are related to the performance of individual strategic leadership tasks or combinations of these tasks. As illustrated in the example of Starbucks presented above, there is a tendency for these core roles to combine certain strategic leadership tasks. In addition, more than one person can perform aspects of a given strategic leadership task. As a result, there is typically overlap between the people comprising the leadership molecule, as shown in Figure 12.3.

Figure 12.3 The Classic Form of the Leadership Molecule

Vision and Culture Role. One classic core role is the person who combines the “vision” and “culture” tasks. This is most often (but not always) performed by the CEO of a company. Sometimes vision and culture are not performed by the same person. It depends upon their competencies and, to some extent, personality. Nevertheless, the classic role is for a combination of vision and culture to be performed by a CEO.

Operations Role. Another classic core role is “operations.” This can be the role of a COO or another executive charged with overseeing day-to-day operations. For example, Howard Behar, who was responsible for the retail stores at Starbucks, was the member of the leadership team responsible for operations, even though he was never COO

Systems Role. The third classic core role is “systems.” This involves responsibility for initiating the need for and overseeing the development of various operational and management systems, ranging from budgeting and planning systems to human resource management and logistics systems. This role might never even appear on an organizational chart, but it exists in the informal organization and in the leadership molecule. It is sometimes performed by a CFO, because that person tends to think in systems terms. It is also often performed by an SVP of HR, or sometimes others. It refers not necessarily to the designer of systems, but to the person responsible for the oversight of the development of systems.

Our prediction is that a more formal role for the systems leadership function will be emerging during the next few years. The occupant of this role will be someone with a strong technology background and capabilities. For example, in 2015, Starbucks announced that it had hired Kevin Johnson, a former chief executive at Juniper Networks with additional experience at Microsoft, as president.8 Mr. Johnson was a member of the Board of Directors of Starbucks and had been engaged with the company's digital operations. In his role as president, he oversees digital operations as well as supervising information technology and supply chain operations. This fits Starbucks' view that the company must “shift to online purchasing for everything from food to clothing by finding new digital strategies to help consumers engage with the Starbucks brand and buy its products.”

Innovation and Change Role. There does not tend to be a defined role for the innovation and change function of leadership; rather, this tends to be performed by the leadership molecule as a whole.

Structural Variations (Forms) of the Leadership Molecule

As in any molecule in nature, there are various structural forms that can occur in an organization. Although the most common structure is a set of three people comprising the leadership molecule, three is not a magic number. Sometimes it is a team of two, and occasionally a team of four.

Where the molecule consists of two people, this is sometimes referred to as “the Dynamic Duo,” a term that owes its origin to the Batman and Robin myth. A good example of this is the duo of Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer of Microsoft. Another example of a duo is Sergey Brin and Larry Page, founders of Google.

Although it is theoretically possible for a leadership molecule to be comprised of five or possibly even more people, we have never observed this in practice. Most often, there is a core team of three people performing the five key strategic leadership tasks. For this reason, we refer to the three-person leadership molecule as the “classic” form or structure.

In the classic form, the first four strategic leadership tasks (vision, culture, operations, and systems) exist as an integrated unit performed by three people. The fifth strategic leadership task—innovation and change—is not shown (as is the case in the classic leadership molecule shown in Figure 12.3) because it is performed by the team as a whole and is not the primary focus of a single individual. The classic example of this form was the H2O molecule at Starbucks.

Another example of this three-person molecule was in operation at Google. Known as “the Troika” (a reference to the three-horse Russian sleigh), it consisted of founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page plus Eric Schmidt, who was hired to be CEO.

In contrast to the leadership molecule as shown in Figure 12.3, there are many times when there are three people who comprise a senior leadership “group” (but not a true team). This is shown schematically in Figure 12.4, where the three people comprise “three atoms in search of a molecule.”

Figure 12.4 Three Leadership Atoms in Search of a Molecule

When the Three Atoms Are Not a “Molecule.” When the three atoms do not come together as a molecule, there can be a significant impact on the organization's effectiveness, and organizational success can be suboptimal. The lack of a molecule can contribute to significant conflict—not only among the people comprising the senior leadership team but also among people throughout the organization as a whole. As a result of the lack of alignment among the three large “organizational gorillas,” people tend to be cautious. They do not want to cross swords or offend any of the senior leadership team, so they tend to keep quiet and proceed with caution. This obviously results in less innovation throughout the organization. It also tends to result in political behavior or “organizational tribes” (silos).

There also tends to be a culture of “you stay out of my territory, and I will stay out of yours.” This leads to a lack of coordination and cooperation. It also leads to a lack of communication across the organization. People will resist change because of the danger of “crossfire” among the organizational gorillas. These symptoms are each problems in themselves. However, they are also symptoms of an underlying systemic problem—the lack of a cohesive leadership molecule.

We have observed several examples of this phenomenon in practice. In one instance, the chairman and CFO were aligned, and the CEO was the odd man out. He was eventually squeezed out of the organization. In another instance, the founder and CEO was isolated from his two most senior leaders, the COO and CFO. The latter were termed the “Ghost and the Darkness” by members of the organization, aptly named after the two man-eating lions of Tsavo, Kenya, that were celebrated in the film of the same name.9

A Complete Leadership Molecule

We believe that to be optimally effective, a leadership molecule must include people who perform all of the five key leadership tasks or functions. However, a molecule can exist where some but not all of the five key leadership task are performed. There can be a two-person unit that performs some, but not all of the key leadership tasks. For example, Apple Computer (now Apple) was founded by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Steve Jobs was the visionary and cultural leader, while Wozniak was the developer of the technology for the Apple Computer. He was neither an operations nor a systems person. As a result, Apple did not have a true or complete leadership molecule. This is termed an “incomplete molecule” and is not likely to be optimally effective. Similarly, at Ben and Jerry's (the ice cream company) both Ben and Jerry were entrepreneurial types who were visionaries and “product guys” and did not possess the other skills required to form a complete leadership molecule.

Design of a Leadership Molecule

What causes a “leadership molecule” to exist? Does it occur by accident, or can it be created by design? What happens to organizational success when a previously existing leadership molecule disintegrates?

A leadership molecule can occur as a natural by-product of day-to-day operations as well as by design. Managers understand that they should be a “team.” As they work together, a true team can emerge. This means that the group thinks of itself as a team and that it has defined but overlapping roles corresponding to the five core roles of the leadership molecule.

Leadership molecules can also be created by design. This involves (1) defining the core roles (as described above), (2) selecting individuals to occupy or perform those roles, and (3) developing a true molecule. The first two are analytic steps. The third is a process of creating a true team from a collection of individuals. This was the process (described above) that was used at Starbucks.

Empirical Support for the Leadership Molecule Model

Recent empirical research has supported the existence of the leadership molecule and its positive impact on organizational performance.10 Specifically, the purpose was to (1) test whether the five hypothesized strategic leadership tasks actually exist as independent variables or “leadership factors”, and (2) the extent to which the presence or absence of a leadership molecule impacts organizational development and, in turn, performance.

The test was executed as part of an executive coaching program conducted for 40 very senior leaders of companies in China. All 40 participants were enrolled in the “CEO Leadership Program” at the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business, Beijing and Shanghai, China. The intent of the program was to enhance the leadership skills of the participants.

Participants were asked to complete two surveys: (1) the Leadership Profile Survey and (2) the Organizational Effectiveness Survey. The Leadership Profile survey instrument was designed specifically for this project to assess each leader's perception of the requirements of their roles in terms of the five key strategic leadership tasks, as well as their perceived capabilities with respect to effectively performing these tasks. The Organizational Effectiveness Survey (discussed in Chapter 2) had previously been shown to have predictive validity as a leading indicator of financial performance.11

Using cluster analysis, the research confirmed the existence of these five strategic leadership tasks in managing entrepreneurial organizations. In addition, the research also confirmed the hypothesized relationship between the existence of a leadership molecule and organizational effectiveness. Specifically, a regression analysis indicated that there was a statistically significant relationship between the existence of the leadership molecule and the measures of organizational effectiveness. It was significant at the 0.001 level! Stated differently, this indicates that the existence of the leadership molecule is related to organizational effectiveness, which, in turn, is a driver of financial performance. There was also a significant negative relationship between the leadership molecule and the severity of growing pains in rapidly growing entrepreneurial businesses. Specifically, where a molecule existed growing pains were less severe than where a molecule did not exist.

The Leadership Molecule at Different Stages of Growth

Previous sections of this chapter presented the basic concept of the leadership molecule and identified the key strategic leadership tasks that need to be performed by members of the molecule. This section discusses how the leadership molecule can or should differ at each of the stages of organizational growth.

Stage I: New Venture

During the first stage of growth, there is not likely to be a leadership molecule. During this stage, a single strong leader tends to perform all five strategic leadership tasks by himself or herself, unless the firm is founded by more than one person. In circumstances where a company is founded by more than one person, there is sometimes a predetermined division of labor that approximates a leadership molecule. However, it also happens that when there are two (or even sometimes more) people involved, they will not necessarily comprise a true or “complete” leadership molecule, as cited in the examples of Apple and Ben and Jerry's described above.

Stage II: The Expansion Stage

As the organization evolves in the expansion stage, there still tends not to be a true leadership molecule. Companies in Stage II will not typically have the resources required to hire people with the differentiated skills required, and it will still tend to be managed as a one-person band. As the company grows in size, the need for a leadership molecule will increase. It is theoretically possible for a classic three-person molecule to exist at Stage II, but not likely. It is more likely that there will be a two-person molecule, with a CEO performing the core function of vision and culture management, and a partner performing operations. Systems will be basic and possibly shared by the leadership molecule duo, or possibly will be the handled by a financial person.

Stage III: The Professionalization Stage

By the time the organization reaches Stage III, the molecule is increasingly necessary, but possibly not in existence. At this point, the company will have the need and the resources to recruit and hire the people required to create a true leadership molecule. The people added should complement the skills and focus of the entrepreneurial founder. It should be noted that the need and the resources available to create the molecule will be less in the early phases of Stage III than in the later phases.

By mid-Stage III (or about $50 million in revenues), the organization is likely to have a COO focused on operations with the CEO focused on vision and culture. The third person in the molecule at this point can be either a CFO or an HR person. It should be noted that while the classic form of the molecule is a CEO focused on vision and culture, and a COO focused on operations, and someone else focused on systems, the functions can be rearranged differently.

Stage IV: The Consolidation Stage

By the time an organization reaches Stage IV, the leadership molecule ought to be in place. Most likely it will be a three-person molecule in the classic form. However, if the leadership molecule does not exist by Stage IV, the organization is not likely to be growing and developing optimally.

The existence of a molecule at Stage IV is one of the secrets to the success of high-performing entrepreneurial companies like Starbucks. In addition, our published empirical research has shown that there is a statistically significant relationship between the existence of a leadership molecule and the extent to which a company has developed the appropriate systems, processes, and so on to meet current and anticipated needs.12

By Stage IV, it is also possible to have a four-person leadership molecule. This is likely to be the classic three-person molecule plus a fourth person who performs special functions, such as acquisitions or special projects. This is where an organization might differentiate between the two versions of the molecule with nicknames such as “the Gang of Three” and “the Gang of Four.”

Stage V: Diversification

By Stage V, a molecule should now exist at the corporate level, and be roughly similar to Stage IV. However, molecules should also be forming at the divisional levels, as well. It must be noted that occasionally (quite rarely) a molecule does not appear to exist at Stage V. If it does not exist, there are likely to be significant growing pains.

One area of the world where we have observed a lack of a leadership molecule at Stage V is Asia, and in particular China. Traditionally, China is a place where there is typically a strong individual (male or female) who is “emperor” of the business, surrounded by “helpers.” Although there are some exceptions, there is typically one true decision maker, not a leadership group. Even in Japan, where there is often the surface appearance of group decision making, the reality is that of a “kabuki dance,” an activity or event that is designed to create the appearance of a search for consensus when it is actually a ritualized “dance” of ultimate public submission to the will of the prevailing emperor.

Stage VI: Integration

By Stage VI, molecules are likely to exist at divisional as well as the corporate level. For example, at Berkshire Hathaway, there is a corporate molecule of Warren Buffett and Charles Munger. Where molecules do not exist at either the corporate or divisional levels, an organization is not likely to function optimally.

Stage VII: Decline and Revitalization

At Stage VII, it is doubtful that a single “heroic” leader might well be able to perform all of the strategic leadership functions required by revitalization. The reversal of decline will typically require a leadership team. One leader might be the “face” and “voice” of a team, but undoubtedly a team will be required. When Howard Schultz returned as CEO to Starbucks, he quickly put a team together. In a personal communication during his visit to UCLA to receive the John Wooden Global Leadership Award, he told Eric Flamholtz that he tried to hire Howard Behar and Orin Smith to come back to help him (thus recreating their leadership molecule); but they had retired and were not willing to return.

Implications of the Leadership Molecule for Building Successful Organizations

During the early stages of organizational growth, a single “heroic” leader may well be able to perform all of the strategic leadership tasks. However, as the company grows in size, the need for a leadership molecule will increase. Further, where this molecule has existed and then “disintegrates” (e.g., Starbucks), the company's fortunes are likely to decline, sometimes precipitously. The short-term decline at Starbucks during 2007 can be attributed to the disintegration of their original leadership molecule, consisting of Howard Schultz, Howard Behar, and Orin Smith.

The molecule model of leadership also has implications for executives, boards, and venture capitalists. The first is that executives who comprise a company's senior leadership need to ensure that they are individually and collectively performing the five key strategic leadership tasks. However, at present, people do not think in terms of this construct since it is not developed in the literature. A comprehensive search of the literature indicates that this concept does not exist and is novel.

Since boards, executives, venture capitalists, and others do not think about company leadership in the way we are suggesting here, the creation of a true leadership molecule occurs currently only by chance or accident alone. What is proposed here is that its creation must become a specific organizational objective. When Howard Schultz sought to replace himself and his core team at Starbucks, it is doubtful that he thought in terms of a leadership molecule. He hired Jim Donald, an experienced retail executive from Walmart, who was ultimately fired. The problem was as much Schultz's failure to recognize the need for a leadership molecule as it was a lack of competence by Donald.

Another implication for action is that it is not just a matter of putting together a set of ad hoc individuals to create the molecule; they need to be able to effectively combine—that is, work together—in a manner that supports organizational development. This typically will require some team building—either time for the molecule to gestate naturally or to accelerate its development through coaching and special team-building activities.

The concept of the leadership molecule suggests that boards that are responsible for selecting company CEOs need to focus on the entire executive team—working to ensure that the team possesses the core “atoms”—versus selecting a single individual. Similarly, venture capitalists need to build a top management team capable of successful scale-up of a new venture so that, for example, it becomes Starbucks rather than Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf or any other similar company.

The message can be applied in the real world because it provides a template for building a successful top management team. It identifies the competencies required and the need for the individuals to function as a true team rather than a collection of individuals.

Summary

This chapter has provided a framework for understanding and enhancing leadership effectiveness—to support effective day-to-day operations and to support the organization's long-term development. On a day-to-day basis, effective leadership involves choosing the “best style” (that is, one that fits the situation) and regularly (and effectively) performing five key tasks—setting, communicating, and monitoring performance against goals (goal emphasis); helping people work effectively together (interaction facilitation); ensuring that each direct report has what he or she needs to perform their work (work facilitation); providing effective feedback (supportive behavior); and developing the people on their teams (personnel development). Those at the most senior levels of the organization also need to perform the five tasks of strategic leadership—creating and communicating a vision, managing the organization's culture, overseeing operations, developing and managing organizational systems, and managing innovation and change. As organizations grow, these five key leadership tasks need to be performed by a leadership team, which, to function effectively, needs to become a true molecule.

The ultimate leadership challenge for an organization over its life cycle is to transition from a “lone wolf” leader into a true leadership team. The leadership “pack” (or leadership molecule) is stronger than any individual leader. This chapter deals with the concept of a leadership molecule, what it means, and how it can be developed. The existence of a leadership molecule in an organization is a hidden success factor and a valuable intangible asset.