Chapter 3

Personas: Powerful Tool for Designers

Robert Chen

LG Electronics

Jeanny Liu

University of La Verne

Introduction

During the past decade, personas in product design have received much attention from academicians and innovative companies (Blomquist & Arvola, 2002; Chapman & Milham, 2006; Faily & Flechais, 2011), an interest that is part of a positive trend toward building user-centric products. Personas provide designers with a user-centric reference tool that depicts an ideal user (Cooper, Reimann, & Cronin, 2014). This tool allows designers to maintain focus on the ideal user as they explore and develop solutions. This chapter explores personas as a practical tool for design. Many of the examples are software and technology oriented, but personas apply similarly to other product categories. We organize this chapter into several sections:

- Defining personas—practical descriptions, underlying bases, and common types

- Importance of personas—exploring the power of using personas during product development:

- During design

- During development

- As a communication tool

- Creating personas—an overview of creating personas from ethnographic research

- Illustrative application of personas—an example from three areas during product development

- Limitations of personas—constraints and mitigation

In this chapter, we define designers broadly as cross-functional members of a team tasked with developing user-facing product solutions. We define user-facing solutions as product features with which users interact and experience. Personas are particularly useful for designers who work on user-facing solutions.

3.1 Defining Personas

Personas are a representation of ideal or prototypical end users, based on behaviors and motivations of real people (Cooper, Reimann, & Cronin, 2014). Personas represent clusters of users from research and are not derived from stereotypical assumptions (Cooper, Reimann, Cronin, & Noessel, 2014). Personas allow designers to relate to and empathize with users, and encourage them to view product problems from a user's perspective. Personas are created at the beginning of the design process. As representations of users, personas define both the target user and the problem for a design team. Minor iterations can be made to personas, but major revisions reset design to the beginning.

Two nonuser personas are often considered during design: the buyer persona (Scott, 2013) and the anti-persona (Cooper et al., 2014). In this context, we refer to buyer personas to signify those who make purchase decisions but do not necessarily use the product. For example, when an airline purchases a plane, pilots represent one user persona and passengers another. Pilots might be consulted during purchasing, but the buyer is usually a business decision maker at the airline—another persona. The buyer persona has disparate considerations for the purchase of an airplane. For example, a buyer considers financing, passenger capacity, maintenance costs, flying range, and fuel economy. Another example of differences between buyers and users can be found in children's products. Parents are buyers, concerned with child safety, purchase cost, and the ability to return a product. Modeling a buyer ensures that a product solves their concerns. Depending on the product, buyer and user personas can be the same person or different people.

Anti-personas illustrate actors who are not the intended users of a product (Cooper et al., 2014). Consumer product designers often create both user and anti-personas to differentiate targeted users from others. For example, a high-end, digital, single-lens reflex (SLR) camera targets expert users and photographers; the expert consumer is the user persona and the anti-persona is the casual consumer, focusing designers on designing a product for an expert. Labeling, memory storage, carrying cases, user manuals, and so on are designed for the expert consumer. Any infrequent or edge cases for the user persona that are common use cases for the anti-persona are ignored. Edge cases are experiences that influence some or all users, but occur infrequently (Cooper et al., 2014). One example of how anti-personas are used for a camera product asks, “What if the user does not understand the basics of operating a camera?” The issue is an edge case for the user persona but is a common-use case for the anti-persona. Since this applies to the anti-persona, design would ignore this issue.

3.2 The Importance of Personas

Personas during Design

Personas form the basis of problem definition for a designer; they define users and set parameters for design solutions, keeping designers from falling into a common design pitfall: designing for oneself (Cooper et al., 2014). Consciously or not, designers often infer and assume about users based on work experience and industry knowledge. Consequently, personas can be useful to avoid self-referencing, frame design problems from a user's perspective, and focus designers. Design teams often use brainstorming and storyboarding as tools for generating and exploring ideas. Brainstorming is the freeform generation of ideas, with minimal constraints or thought to feasibility. During ideation or concept phases, brainstorming facilitates conversation. Combined with appropriate personas, brainstorming allows designers to engage and express ideas for subsequent reflection. Storyboarding is a second example of when personas combine with another design tool during design. A storyboard is the visual telling of the story. Designers often storyboard ideas early during a concept phase to visualize either a problem or a solution, and sometimes both. The storyboard's protagonist is the persona, allowing a design team to form deeper empathy for users.

Personas during Development

During development, personas get an engineering team up to speed quickly. A clearly defined persona makes it easier for designers and engineers to achieve a common understanding about a user and the scope of a solution. It is critical that engineers understand the target persona so they can make the right decisions and trade-offs. For a flexible, iterative process, it is impossible and inadvisable to document every detail during design. To compensate, personas provide contextual understanding to an engineering team so it can interpret design documents.

Another benefit of personas is managing edge-case discussions between engineering and design (Cooper et al., 2014). A common design challenge is determining whether an edge case is important. Personas provide a reference point from which communication can be more efficient between designers and engineers. If an edge case is important to the persona, it should be part of the design. For example, the cockpit of a commercial airplane is designed for highly skilled and experienced pilots and crews. The cabin crew and passengers are not expected to be able to operate the controls in the cockpit. Consequently, a designer's persona is the pilot. The edge case of what happens when all capable pilots are unavailable is not a viable use case.

For a typical smartphone app, one edge case asks, “What happens if the user does not have an Internet connection?” The answer depends on personas defined for the app. Internet browsers on smartphones offer limited functionality without an Internet connection because designers determined that their personas understand how browsers behave without an Internet connection. Personas are useful to a development team so engineering can understand the scope of its work, and the quality assurance (QA) team will not waste time testing irrelevant edge cases.

Personas as a Communication Tool

Personas are useful when it comes to communicating with other business functions such as marketing, management, and sales. Personas provide a clear definition of a target market and assist a marketing team with aligning a product from inception through promotion. Buyer personas provide sales and marketing a method of collaborating with the design team. Pitching a product concept to executive managers in a corporation or potential investors (e.g., in a start-up company) involves communicating abstract, contextual information. Personas help decision makers understand a problem from a user's perspective and provide a context for evaluating the product concept. Therefore, personas are useful for obtaining corporate support or financial investment for a start-up.

3.3 Creating Personas

When creating personas, the first step is to identify and select a group of users to research. Choosing users who belong to an appropriate market segment is key to yielding useful insights, often requiring a product manager to possess intimate knowledge of a market and various market segments in the industry. In practice, product managers often rely on secondary research and internal records or conduct a small-scale study to define various personas.

The next step is to collect data. Ideally, personas are created by clustering or consolidating real-life people and experiences from primary research that includes ethnographic studies and user interviews (Cooper et al., 2014). Ethnographic research is the deep, qualitative study of users in the context of their environment when using a product. There are various methods for collecting data during an ethnographic study. We often conduct user interviews, conduct observational studies, and (if possible) use video recordings of users using a product and photos of their environment. Interviews uncover user problems and their underlying causes. Interviews help designers understand user motivation and a user's state of mind while using a product. However, user responses alone are unreliable since users are often unaware of their own needs (Rosenthal & Capper, 2006). Mixed methods may explore user needs more fully. Observational studies and video recordings capture users performing tasks, techniques that are effective when conducting efficiency studies. Using these methods, ethnographic research is a reliable source for uncovering behavioral responses and user problems. When capturing a user with video, audio, or photos, researchers must always ask permission from the user before recording and guard the user's privacy.

The third step is consolidating data from the studies and grouping insights based on common user problems. Often, this is done with a broader design team so all designers have the opportunity to learn directly from the researchers. This also offers the advantage of building personas with the designers so they can internalize user models. Researchers typically look for patterns in responses and organize them into clusters, which are then grouped based on common user problems. Researchers sometimes find that users from multiple market segments share similar problems.

Finally, the team examines the notes and merges various clusters to create a series of personas. The team looks for a dominant profile or common demographics within the cluster. The profile becomes the basis for a persona as long as it does not focus on a single, real person. The team also looks for attributes of its subjects that are impacted by the user problems, and build these same attributes into the persona. For example, a busy, active lifestyle might be an important attribute in the cluster of test subjects. The persona built from this cluster must have this same trait. Although we discuss user personas, the same reasoning extends to nonuser personas, which must also be based on data. Various clusters of problems coalesce into personas, and prioritization of these personas determines which represent personas and anti-personas. Buyer personas can be different people from users, and separate ethnographic interviews might be needed to study them.

3.4 Illustrative Application of Personas

This example is based on a software product, though application of personas is the same for other types of products. Although it is common for a design team to work with multiple personas, we demonstrate only two—one user and one anti-persona—for the purpose of expediency.

Product Manager at ACME

The example begins with Anne, an experienced product manager at ACME Tech, a technology company that makes a variety of productivity software for consumers across devices: personal computers, smartphones, and tablets. ACME's business model is to provide products free for users to download, and include advertising from third parties in the products. ACME receives the bulk of its revenue from advertising. Anne works on the company's mobile-apps team, which makes apps for smartphones and tablets. According to ACME's marketing team, there is an opportunity in the marketplace for a better-productivity mobile app. The marketing team sends her an analyst's report that suggests all mobile productivity apps in the market are disappointing and used rarely. Anne is excited and wants to seize this opportunity to launch a new app for smartphone users, with the goal of adding new customers and expanding ACME's customer base.

- Stage 1: Creating personas. With her goals firmly in her mind, Anne turns to a colleague on the user research team, and commissions an ethnographic study. Her colleague recruits eight highly productive users in Texas for the study. The researcher recommends that Anne and any interested members of the design team help her with the interviews. Anne thinks this is a great idea and convinces a few designers and engineers to participate as interviewers, observing in pairs during the series of ethnographic studies. After completing the studies, Anne and her cross-functional team review the data under the guidance of the researcher. After an initial review of results, Anne organizes a working session to cluster information from the interviews and derive personas. All the designers and engineers who participated in the interviews attend Anne's working session. Two dominant profiles emerge: a tech-savvy, self-employed persona and a tech-aware, corporate persona. From the original market-segmentation data, many of the segmentation characteristics were deemed not useful while clustering subjects based on user problems. The dominant attributes that mattered were willingness to adopt new technology and corporate versus noncorporate work background. Anne found some indication that users who looked for new technology were most dissatisfied with existing productivity solutions. Aware that there were only eight interviews conducted during the study, Anne commissions a survey to validate results. The survey results validate the initial findings. At this point, Anne is ready to build personas. Mindful of how personas can be misused, she decides to name her personas Wilma (the tech-savvy, self-employed) and Fred (the tech-aware, corporate). These personas will be used as a point of reference throughout the project (Figures 3.1 and 3.2).

- Stage 2: Method of inquiry based on personas. Anne wants to frame the user problem for the designers so she uses the personas to represent the target users. Anne organizes a series of brainstorming sessions with the cross-functional design team to discover ideas for exploration. Although the design team is familiar with user research, Anne presents her personas and tapes a printout of each to a whiteboard in the conference room used for the brainstorming session. During the session, all participants can be reminded of the intended users of their ideation brainstorm. Anne uses the personas to set the context and ensure that participants focus on generating ideas that will benefit the target user. Personas play a strong role during the brainstorm by getting designers in the mind-set of thinking of personas before generating ideas. This keeps brainstorming focused on users.

- Stage 3: Communicating with engineering. Although it is early during the design, Anne and the lead designer review results of the brainstorming session with the lead engineer on her cross-functional team to get his technical feedback. They use the personas to summarize their research and frame ideas generated from the brainstorming session. An issue the lead engineer raises is that corporate users encounter integration issues with corporate security and e-mail. He estimates that solving these issues alone will take up the majority of engineering resources.

- Stage 4: Prioritizing personas. Based on the technical feedback, Anne reassesses the personas and decides that Wilma is more important; Fred is demoted to an anti-user persona but is not ignored. Anne knows from the survey data that if she excludes corporate users, she will be leaving out a large pool of potential customers. She plans to go to market focused on the Wilma persona and incorporates the needs of the Fred persona in subsequent versions of the product.

- Stage 5. Concept storyboarding. Based on prioritization of the Wilma persona, Anne and her lead designer return to the design team and reset the team's focus. They review brainstorming ideas, and three stand out as being interesting for Wilma.

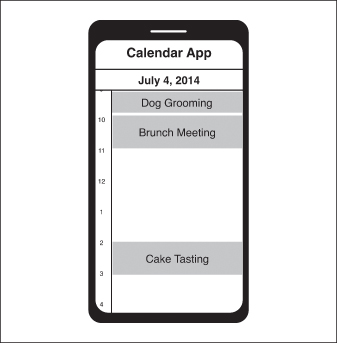

Figures 3.3 through 3.6 comprise a simple story board that Anne uses to describe a use case of how her persona (Wilma) uses the software product.

Figure 3.3 Anne's storyboard reminder action: Scene 1 (Wilma as a phone call with a client, and they agree to schedule an event in the future).

Figure 3.4 Anne's storyboard reminder action: Scene 2 (Based on the phone call, Wilma creates an action of her smartphone using the new application).

Figure 3.5 Anne's storyboard reminder action: Scene 3 (The action appears automatically on Wilma's calendar).

Figure 3.6 Anne's storyboard reminder action: Scene 4 (The action e-mails client automatically about the appointment so the client can confirm).

To understand each product concept better so the team can decide, each concept is storyboarded. Using Wilma as the protagonist, Anne and her design team sketch the three concepts with a storyboard for each. Figures 3.3–3.6 are a storyboard for one of the product concepts: the reminder action. The storyboards describe how Wilma will use and benefit from the concept. After each concept is storyboarded, they evaluate all concepts together, choosing the reminder action as the focus for their app.

- Stage 6: Interpret and communicate design proposals to stakeholders. Anne uses the personas to communicate and pitch the design team's concept to ACME Tech's product committee for approval. During the presentation, there was insufficient time to delve into the details with the committee on the ethnographic user research. Anne uses the personas to get the committee to empathize with the target personas. Anne takes the committee through the problem scenarios using the personas. She uses Wilma as the voice when describing how dissatisfied users are with existing productivity apps. Anne's intent is to get the committee to view potential opportunities and challenges from the target user's perspective. Her presentation goes well, and the committee approves the project.

- Stage 7: Working with engineering. With the approval to build the app, Anne is able to add software engineers to her cross-functional team. As part of the induction meeting for the new engineers, Anne introduces them to the basic ethnographic user research that she and the cross-functional team used. Anne then introduces her two personas and gets the engineers to understand Wilma as the user persona and Fred as the anti-persona. She gives every member of the cross-functional team a printed profile of Wilma to post at their desk so they are reminded that they are creating an app for a specific type of user—Wilma.

3.5 Summary

Anne and her cross-functional design team originally created personas after reviewing the ethnographic user research, and she clustered results in a way that made sense for her productivity app idea. She validated findings using a survey, allowing her to create personas that summarized the user research findings. Her personas helped her place a human face on the user research information. Anne created two personas (Figures 3.1 and 3.2) but eventually prioritized Wilma over Fred during design. Throughout development, Anne maintained her persona to ensure that all stakeholders focus on the right user model.

Limitations of Using Personas

Although based on data, personas are dependent on subjective decisions—which market segment to study and which user problems to cluster. Product managers and designers create personas at the start of design to frame a problem for the design team, and, consequently, conducting research with real users is the best way to gain insights into user problems; the purpose is to uncover insights the researchers did not know before studying the user. These insights catalyze product innovation. The danger is creating personas too quickly based on existing knowledge held by team members. One study suggests that some teams struggle to relate to personas (Blomquist & Arvola, 2002). Their difficulties consist of poor communication among team members and a sense of distrust for a primary persona. Their persona was based on presuppositions of system administrators and lacked empirical evidence.

A persona is a model, not a substitute for product testing. User testing with real users must validate design solutions derived from personas. To test that personas are valid, begin with original market segmentation data to recruit participants to test the solutions, and observe whether participants respond to the new product solution. In the case of designing a digital camera, if a single expert user persona represents both professional and expert-amateur photographers, user testing must assess this early during design of prototypes. If both expert and amateur photographers struggle with the prototypes, this might signal that the persona was too broad to represent both. Consider a new set of personas that separate the users and revisit the design solutions. Over time as user testing validates both personas and designs, and as the solutions become specific and more detailed, testing recruitment shifts to using persona profiles instead of market-segmentation information.

Prioritizing personas during design is an extremely important and subjective task. Omitting user personas reduces the usability of the product for those users, and omitting buyer personas creates obstacles to purchase and adoption. However, having too many personas dilutes the value of the product. Documenting the goals of a product at the beginning of the definition phase provides a framework for prioritizing personas.

3.6 Conclusion

The purpose of personas is to provide design and development teams with a representation of a target user so everyone shares a focus to build a user-centric product. Personas emerge at the beginning of design because they are part of the problem definition for designers. Multiple personas emerge often, including users, buyers, and anti-personas, and these personas need to be prioritized for a design team. Prioritized personas are powerful tools during design, development, and communication to business stakeholders.

References

- Blomquist, Å., & Arvola, M. (2002, October). Personas in action: Ethnography in an interaction design team. Paper presented at the Second Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Aarhus, Denmark.

- Chapman, C. N., & Milham, R. P. (2006, October). The personas' new clothes: Methodological and practical arguments against a popular method. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 50(5), 634–636.

- Cooper, A., Reimann, R., & Cronin, D. (2014). About face 3: The essentials of interaction design. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley.

- Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D., & Noessel, C. (2014). About face: The essentials of interaction design. Indianapolis, IN: Wiley.

- Faily, S., & Flechais, I. (2011, May). Persona cases: A technique for grounding personas. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2267–2270). Vancouver, BC, Canada.

- Rosenthal, S. R., & Capper, M. (2006). Ethnographies in the front end: Designing for enhanced customer experiences. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 23(3), 215–237.

- Scott, D. M. (2013). The new rules of marketing & PR: How to use social media, online video, mobile applications, blogs, news releases, and viral marketing to reach buyers directly. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

About the Authors

Robert Chen is a Product Manager at LG Electronics Silicon Valley Lab. He earned his bachelor's degree from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and an MBA from Indiana University, Bloomington. He is passionate about working with smart people to create innovative and inspiring consumer-software products. His interests include product innovation, design thinking, and creative management.

Jeanny Liu is an Associate Professor at the University of La Verne's College of Business and Public Administration. She earned her PhD in Marketing from the University of Turin, Italy, and an MBA from California State Polytechnic Pomona. Her research interests include marketing strategy, branding, design thinking, and teaching pedagogy. Her research has been published in the Journal of Marketing, Journal of Organizational Psychology, and Journal of Education for Business. She has received multiple research awards, including the Young Scholar Award by the University of La Verne Academy, and the Drs. Joy and Jack McElwee Excellence in Research Award. Correspondence concerning this chapter should be addressed to Jeanny Liu, Department of Marketing and Law, University of La Verne, La Verne, CA 91750. E-mail: [email protected]