Chapter 8

Integrating Design into the Fuzzy Front End of the Innovation Process

Giulia Calabretta

Delft University of Technology

Gerda Gemser

RMIT University

Introduction

Managers recognize the importance of the fuzzy front end (FFE) for successful innovation (Reid & De Brentani, 2004). During the FFE, the innovation team identifies and selects interesting innovation opportunities, generates and selects ideas addressing these opportunities, and integrates the most promising ideas into product or service concepts for further development (Koen, Bertels, & Kleinschmidt, 2014).

A well-managed FFE will result in better innovation outcomes. However, the FFE remains a challenging step in the innovation process, due to its intrinsic uncertainty and the need to make choices based on incomplete information. Design professionals are particularly helpful for dealing with FFE challenges. Design professionals combine a sense of commercial purpose with a positive attitude toward change, uncertainty, and intuitive choices. Indeed, companies increasingly recognize the important role design professionals can play in the FFE and use them not solely for executing new product/service concepts resulting from the FFE but also for co-creating solutions during the FFE.

In this chapter, we provide guidelines on how design professionals and their practices and tools can help companies overcoming FFE key challenges. These guidelines (and the related examples) are derived from an analysis of prior literature and case studies on innovation projects in which design professionals were involved in the entire FFE, either as external design consultants or as internal design employees.

In the remaining paragraphs, we first discuss three FFE key challenges: defining the innovation problem(s), reducing uncertainty by managing information appropriately, and getting and maintaining commitment from key stakeholders. Then we discuss which and how design professionals' practices and tools can help overcome these FFE challenges. We conclude with advice on how to optimize collaboration with designers in the FFE.

8.1 Challenges in the FFE

FFE activities confront business practitioners with three key challenges for which design professionals' practices and tools are particularly helpful.

Problem Definition

At the beginning of the FFE, defining the innovation problem properly—for example, in terms of the target market, the needs to be addressed, the innovation objectives—can enable firms to identify and select valuable opportunities, which can steer idea generation and concept development toward unique solutions. However, innovation problems are generally complex, ill structured, and highly demanding in knowledge breadth and depth. When confronted with such problems, managers often only identify the most obvious symptoms or those to which they are most sensitive (e.g., current offerings' sales). The resulting problem definition might be too simple or too narrow and lead to new concepts that, for instance, do not follow a portfolio strategy or address only short-term market needs.

Information Management

All FFE activities require significant information management. Given the unpredictability of innovation outcomes, managers tend to reduce FFE perceived uncertainty by collecting as much diversified information as possible (e.g., market intelligence, technological knowledge, financial information). However, given the limitations of human information processing capabilities, simply accumulating information does not necessarily reduce uncertainty. To increase the odds of successful innovation, information should be selectively retrieved, meaningfully organized, and effectively communicated.

Stakeholder Management

Most innovation projects involve different stakeholders to access a broad spectrum of expertise and resources. While this approach is needed to address the complexity of innovation problems, stakeholders' individual objectives and interests (e.g., different departments, institutions/companies, career goals) might differ and even conflict. The resulting frictions may lead to suboptimal problem definition, deviation from initial objectives, and even stakeholders' resistance to engage in the innovation project.

In the following paragraphs, we illustrate how specific design practices—that is, designers' way of working—and tools can support business practitioners in addressing the above-mentioned FFE challenges, thus building a case for a more prominent role for designers in the FFE. These design practices and tools for FFE are summarized in Figure 8.1. Any design professional involved in FFE activities generally adopts the design practices in Figure 8.1, which represent the true added value of designers. Conversely, the design tools can vary depending on designers' preferences or the specific context. Thus, our list of tools is not exhaustive but based on our field research and experience.

Figure 8.1 Design professionals' practices and tools for FFE.

8.2 Design Practices and Tools for Assisting in Problem Definition

Design Practices for Problem Definition

As shown in Figure 8.1, design professionals use reframing and holistic thinking to support innovation managers in making sense of ill-defined challenges and overcoming biased and narrow problem formulations.

Reframing refers to design professionals' practice of stating a problematic situation in new, different, and interesting ways, thus paving the way for more creative solutions (Paton & Dorst, 2011). During the FFE, business practitioners generally define the innovation problem on the basis of their expert knowledge of the company, their information on current sales and market needs, and their past experience. For instance, a typical problem definition for innovation projects aimed at reinvigorating sales would be developing new offerings based on salespeople's suggestions, competitors' offerings, and incremental improvements of current products' technical features. This problem definition might be biased and short-term oriented, leading to new products/services with limited market impact and financial returns. When involved in the early stages of FFE, designers in general try to get to the “problem behind the problem” by means of reframing. Reframing is based on deconstructing a problem into its building blocks (e.g., subproblems and influencing factors) in order to highlight relevant aspects disregarded in the initial problem definition. By generating a different, sometimes broader perspective on an innovation challenge, reframing facilitates opportunity identification and points idea generation in more appropriate directions. Thus, design professionals supporting companies in innovation projects for addressing decreasing sales would take a broader array of influencing factors into account (e.g., lack of a deep understanding of user needs, lack of a clear vision for the industry/company future, lack of a distinctive brand image, narrow view on technological evolution) and reframe the problem definition into, for instance, developing a distinctive style for different user segments and a strong brand identity to incorporate into current and future offerings.

Designers' ability to look at a broader range of influencing factors for reframing the innovation challenge derives from their holistic thinking practice. Holistic thinking involves taking a comprehensive perspective on a problem, recognizing patterns, and making connections on the basis of (experience-based) intuition rather than a thorough analytical process. Through holistic thinking, design professionals can point innovation managers toward relevant, disregarded cues and connections (i.e., influencing factors) for effectively reframing their FFE problem definition.

Design Tools for Problem Definition

Design professionals can use several design tools to support their reframing and holistic thinking practices, including mind maps and metaphors.

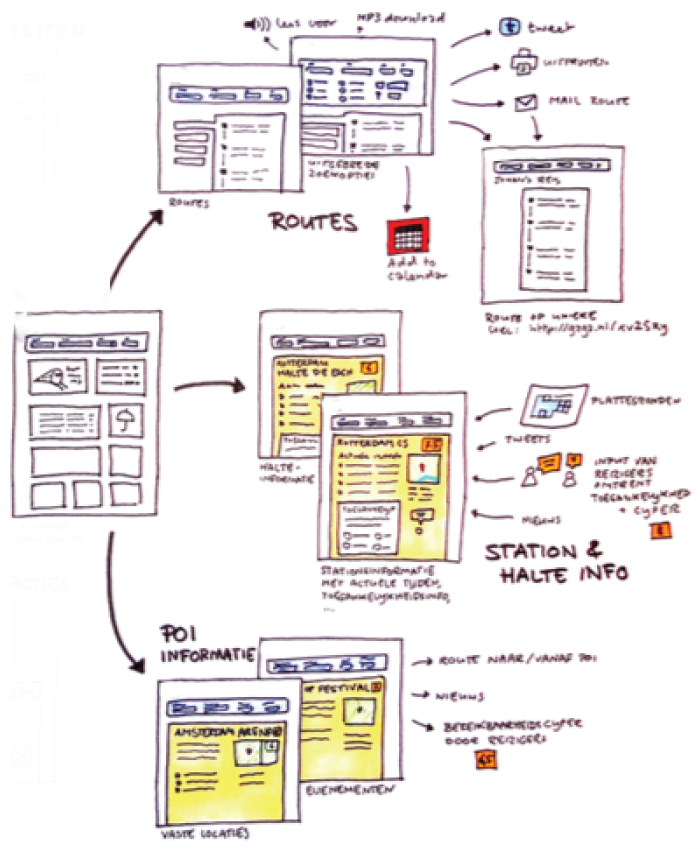

Mind maps are diagrams for visually representing and connecting all the information regarding a certain theme (Buzan, 1996). In problem definition, designers use mind maps for identifying the issues influencing an innovation challenge and illustrating how such issues relate to each other. The resulting map offers a thorough overview that facilitates holistic associations for reframing an innovation challenge. Figure 8.2 provides an example of a mind map made by a design professional to deconstruct the innovation challenge of developing a new website for a public transportation service.

Figure 8.2 An example of a mind map.

The process of developing a mind map should be loose and unstructured to stimulate holistic thinking in identifying relevant factors affecting FFE problems. However, design professionals usually follow the key steps below:

- Write the name or description of the innovation problem (or subproblem) in the middle of a paper or any other drawing area.

- Brainstorm on the major elements/factors/drivers of the innovation challenge, placing the thoughts on departing branches. Design professionals facilitate this step by keeping people engaged in the brainstorming and by maintaining the organic structure of the mind map.

- Identify and emphasize connections (e.g., by using colors, shapes, and connectors).

- Reflect (individually and collectively) on the resulting mind map to trigger new connections and problem reframing.

Metaphors allow for interpreting and illustrating a phenomenon through comparing it with something else (Hey, Linsey, Agogino, & Wood, 2008). In the FFE, design professionals use metaphors for better understanding the innovation context (e.g., the market, the users, the opportunities) and for opening up the problem space initially conceived by the business practitioner. By using compelling figurative expressions, designers' metaphors encourage managers to defer judgment, release the biases with which they approach innovation projects, and develop a deeper understanding of the innovation challenge. Combining metaphors with visual stimuli—as, for instance, in a mood board—makes this tool particularly effective. Mood boards favor a more open discussion, as the images use a metaphorical language, and do not immediately lead to innovation solutions. When creating mood boards, design professionals use images of different objects to convey the essence of a specific user group and to stimulate the client to adopt a future-oriented user perspective when generating new product concepts.

Design professionals usually undertake the following steps to identify and effectively use metaphors for FFE problem definition:

- Define the key elements/factors/drivers of the innovation problem (for instance, by using mind maps).

- Search for a distinct entity, phenomenon, or situation where one or many of the identified elements/factors/drivers occur.

- Use the identified entity, phenomenon, or situation to explain and reframe the initial innovation problem.

8.3 Design Practices and Tools for Assisting in Information Management

Design Practices for Information Management

During the FFE, innovation teams collect, organize, and share relevant information on a variety of factors (e.g., market, technology, competitors) to reduce the innovation uncertainty that could trigger risk-averse behaviors and deviation from truly innovative directions. Professional designers can assist in overcoming information scarcity challenges through their practices of “sensing” future trends, brokering knowledge from different fields, and making information easier to grasp by translating, condensing, and animating information.

First, when gathering information, design professionals use their human-centered orientation and tools to “sense” future trends and emerging people's needs and concerns. This sensing practice enables design professionals to generate new and more authentic insights on users and the market environment.

Second, designers' knowledge brokering practice—that is, the practice of transferring market and technology knowledge acquired in prior projects and different industries to current projects and industries—helps greatly in FFE information management. Through knowledge brokering, designers mobilize knowledge domains apparently unrelated and not regarded as relevant. This not only increases the chances of detecting untapped opportunities, but also reduces FFE uncertainty since designers' (positive) experience in other industries is regarded as valuable grounding for new directions.

Once information has been gathered, designers support its sharing through their practice of translating, namely, converting information from one language to another (e.g., verbal to visual and vice versa; tacit to explicit and vice versa) so that it is usable by a broader audience. For instance, a mood board exemplifies the translation of verbal language—that is, the text description of brand values and market information—into a visual language that makes the information easier to use for generating better and more innovative concepts.

Designers' practice of condensing information is also important for the FFE. FFE-related information can be unstructured, disconnected, and overwhelming, thus challenging managers' information processing capabilities and generating uncertainty. Given their familiarity with complexity, designers can help companies sort insights, highlight key data, and combine them into relevant knowledge. Additionally, designers use visualization and materialization to communicate the condensed information in an engaging manner (animating), thus facilitating knowledge internalization and subsequent usage for identifying and pursuing truly new opportunities. Due to the effectiveness of the condensing and animating practices, an increasing number of design agencies, such as XPLANE, JAM, and INK, are specializing in offering visuals (e.g., infographics, animations, posters, digital visualizations) for condensing complex information (e.g., market intelligence, technical knowledge, company information) into comprehensive, clear, and engaging images.

Design Tools for Information Management

For enacting the above-mentioned practices, designers use several human-centered tools, including context mapping, customer journey mapping, and personas.

Context mapping is a qualitative design research method to uncover deep insights on how users experience a product or a service (Sleeswijk Visser, van der Lugt, & Stappers, 2007). Such insights deepen the FFE information base and help in finding more innovative solution spaces. In context mapping, participants are provided with generative tools (e.g., prototypes, photo cameras or recorders, diaries) to map their experience with a problem or a product/service category in an engaging manner. For instance, an organic food retailer asked potential consumers to fill in a verbal and photographic diary of their grocery shopping and food preparation habits to discover innovation opportunities. The simple and engaging diary tasks made respondents more aware of their experiences and enabled them to provide deeper insights on their grocery shopping behavior during the subsequent in-depth interview. Since the context mapping exercise usually generates lively answers and compelling visualizations (see Figure 8.3), design professionals use the exercise not only to identify opportunities, but also to engage business practitioners with their potential customers' life.

Figure 8.3 An example of the outcome of a generative tool.

Customer journey mapping is a tool for mapping all the stages a customer goes through when using a product or a service (Stickdorn & Schneider, 2012). By covering customers' emotions, goals, interactions, and frustrations, the journey map provides a thorough view of the customer experience, highlights untapped opportunities, and stimulates idea generation. Figure 8.4 shows the customer journey of a train traveler.

Figure 8.4 An example of a customer journey.

Developing informative customer journeys requires time, effort, and the involvement of cross-functional teams with complementary competences (including design professionals for their intrinsic human centeredness). The following steps should be undertaken:

- Define the subject of the journey (i.e., the type of customer) specifically.

- Use a horizontal timeline to chronologically map all the activities a customer goes through when using a certain product or service, or when completing a certain task, including the before and after. Taking the customer's point of view is essential to keep the focus on activities rather than physical touch points.

- Characterize the identified activities by describing the customer's aims, emotions, frustrations, challenges, and satisfactions. Both this characterization and the previous mapping could be supported by qualitative research such as in-depth interviews with customers.

- Discuss the customer journey with different stakeholders (including customers) to identify opportunities related to the mapped activities.

Personas (see also Chapter 3) are fictional representations of current or potential customers describing and visualizing their behaviors, values, and needs (Pruitt & Adlin, 2010). In the FFE, design professionals use personas for summarizing and communicating the findings of market research in an engaging manner, for developing a shared user focus across different stakeholders, and for generating new ideas and concepts. The main strength of personas is their cognitively compelling nature, due to the fact that they give a human face to otherwise abstract customer information. Figure 8.5 offers an example of a persona (“Anna”) for public transportation travelers.

Figure 8.5 An example of a persona. |

“I like working on the train, so I go for those I think are less crowded.” “I don't use public transport during the weekends.” “I need to be on time!!!” “I wish it would be easier for my parents to use public transport to visit me.” |

||

| Name | Anna | Interests | Likes sport (morning runs, tennis, yoga). Loves dinners with friends in restaurants. Can't live without her mobile. |

| Age | 31 | Home life | Lives with her boyfriend and a dog, commutes four days a week, does not want a car, has a salary allowing for two long exotic trips a year. |

| Working | Brand manager in a multinational | ||

| Background | Got her master's degree at 25, still thinking about doing a PhD. | ||

The design professionals developed Anna for making the innovation team aware of authentic user needs and for embedding the user perspective in key decision moments (e.g., for discarding innovation directions that were not user centered).

Design professionals usually follow the steps below for creating personas:

- Broadly define the type of customer for which personas should be developed (e.g., public transportation travelers).

- Collect customer information from different sources (e.g., market research, expert interviews, desk research).

- Based on the data, identify key characteristics that create differentiation within the selected type of customer (e.g., likes/dislikes, needs, values, interests). Normally, demographic characteristics are not considered at this stage.

- Identify, name, and characterize three to five different personas within the selected type of customer.

- Visualize each persona through pictures (e.g., their face, their activities, visual elements from their context), demographics (e.g., age, education, job, family status), representative quotes, and affective text.

8.4 Design Practices and Tools for Assisting in Stakeholder Management

Design Practices for Stakeholder Management

As shown in the bottom row of Figure 8.1, design professionals engage stakeholders in the FFE by continuously inspiring them through new perspectives, insights, and approaches to FFE challenges. Thanks to their future orientation, their openness to exploring new ideas, and their use of compelling visualizations for working and communicating, design professionals help business practitioners suspend risk-averse judgment and embrace new innovation directions.

Design professionals also use co-creating as a practice for generating and maintaining stakeholders' commitment to the FFE over time. Specifically, in all the FFE activities in which stakeholders are involved, design professionals stimulate their active participation and frequent interaction. Through co-creation, design professionals encourage stakeholders to consciously devote cognitive effort to FFE activities, ensuring that they develop ownership of the project and of its innovative outcome.

Personal interests and hidden agendas might inhibit an effective FFE, particularly when many different stakeholders are involved (e.g., in network innovation projects or in innovation projects for the public sector). Design professionals can help clients align different perspectives (integrating), by leveraging their outsider and expert status and by pushing the user perspective as a decision-making criterion for achieving agreement during the FFE. By immersing themselves in user experiences, business practitioners are less likely to base their decision making exclusively on their own perspectives and interests, thus becoming more open to alternative solutions with more market potential.

Design Tools for Stakeholder Management

Tools supporting designers in stakeholder management include storytelling, early prototyping, generative sessions, and stakeholder mapping.

Storytelling (see also Chapter 7) refers to the use of visual and verbal narratives for conveying information (Beckman & Barry, 2009). Communicating through storytelling offers a more compelling and effective way of delivering information than using “dry facts,” thus helping designers develop trust and commitment across stakeholders. Storytelling can focus on explaining use and usability challenges (informative story) or on simply creating emotional connections between customers and stakeholders (inspiring story). Both types of stories may help stakeholders generate ideas and agree on interesting innovation directions. Figure 8.6 shows an example of a storyboard used by design professionals to convince a provider of public transport services that a more user-centered travel information website could substantially improve travel experience.

Figure 8.6 An example of a storyboard.

Early prototyping (see also Chapter 7) permits the testing of different ideas and concepts in a rapid and iterative fashion. Through early prototyping, design professionals provide tangible artifacts that allow stakeholders to experience more vivid manifestations of the future and eventually develop commitment to new directions. Designers for a consumer electronics manufacturer used early prototypes to develop digital services for their high-end coffee machines, and to persuade business stakeholders to transform their revenue model from selling high-end products to selling product-service systems. Due to the “hands-on,” iterative working style, the use of early prototypes increased business stakeholders' sense of ownership and commitment, which were essential to take the digital service innovations to the market.

Generative sessions are used in connection with context mapping and usually entail inviting users to share their experiences and engage in activities in which they express their views on new product ideas and concepts. Design professionals use generative sessions also with FFE stakeholders in order to stimulate them to share their experiences, views, and opinions and break the silos that might prevent a fruitful collaboration. To prepare for these sessions, participants are given a specific task and generative tools (such as cameras or diaries) to allow them to record specific events, feelings, or interactions. These tasks and creative facilitation techniques during the sessions help stakeholders reflect on their ideas and motivations, and to open up to the discussion. The results of a generative session are never definitive, due to the high amount and the raw form of the generated insights. Thus, while the objective of creating stakeholders' agreement and commitment should be achieved during the session, its outcomes are normally further fine-tuned ex-post by the design professionals.

Stakeholder mapping is a tool for visualizing the stakeholders involved in a project and their interests, relationships, and interdependencies. Design professionals use stakeholder maps in the FFE as the cornerstone for building a common agenda. Although interests, relationships, and interdependencies may be highly dynamic and nontransparent, a stakeholder map provides an initial overview for the early detection of stakeholder-related opportunities or obstacles to effective FFE. Additionally, many design professionals use stakeholder maps dynamically, by introducing game elements to monitor the evolution of stakeholders' interests, relationships, and interdependencies over time. Value pursuit is an example of a dynamic stakeholder map using two radar maps to respectively identify the stakeholders and monitor them throughout a project. The first step in building this map is identifying the most relevant stakeholders. Each stakeholder is then placed in one of the sections of the radar map. The identified stakeholders are subsequently described in terms of their expectations, contributions, and struggles they might experience in the innovation project. This first step is visualized in Figure 8.7, where the numbers listed at the outer rim of the map (1 to 7) each represents a stakeholder. Stakeholder positions are represented by placing pieces on a second radar map visualizing how much each stakeholder gives and takes in an innovation project. The map is updated at different moments in the FFE, to check if and how stakeholder positions change over time. Design professionals usually co-create this map with the stakeholders, thus leveraging the mapping process itself for facilitating stakeholders' mutual understanding.

Figure 8.7 Value pursuit for stakeholder mapping: Step 1.

© Karianne Rygh, in collaboration with CRISP Product Service Systems 101 research team.

8.5 How to Integrate Design Professionals in FFE

In the prior sections, we showed how integrating design professionals and their practices and tools in the FFE helps to address some key FFE challenges. However, design professionals' strategic integration in the FFE is still not the norm but occurs only in companies with a design-oriented corporate culture. In this section, we describe some tactics developed by business practitioners and design professionals to achieve this strategic integration. The principle underlying these tactics is that design practices should complement rather than substitute for business practices in the FFE, and that design tools should be applied together with business practitioners to co-create the key outcomes of the FFE (i.e., new ideas and new concepts). Thus, in the FFE, design professionals should work with (rather than for) business practitioners. The identified tactics include:

- Building a long-term, trustful relationship between business practitioners and design professionals. The chances of successfully integrating designers' practices and tools in the FFE increase if there is a long-term, trusting relationship between business practitioners and design professionals. After repeated, satisfactory transactions, business practitioners can assess the quality of the design professionals' practices and tools and progressively involve them in strategic innovation activities such as helping to identify and select opportunities. Under conditions of uncertainty (like in the FFE), team composition is often driven by personal trust based on prior experience. Once established, experience-based trust enables reciprocal and enduring relationships.

- Developing mutual understanding. Both business practitioners and design professionals should invest in empathizing with each other's way of thinking and acting. To build the trust needed for playing a central role in the FFE, design professionals need to quickly develop a deep, authentic understanding of the innovation project and of the needs, objectives, and challenges of the business practitioners with whom they are working. Designers' empathizing efforts (e.g., generative sessions, asking the right questions, adjusting to the specific work environment in terms of, for example, language or clothing used) help to develop this mutual understanding and trust. However, business practitioners should be open to the intuition-driven practices and tools of the design professionals. As business practitioners are more familiar with analytical, linear, and quantitative tools, they might be skeptical about the appropriateness and effectiveness of designers' tools and practices in the FFE.

- Preparing the ground. This refers to practices that explicitly or implicitly prepare business practitioners for undertaking FFE with an integrated intuition–rational approach. As noted earlier, this is often needed, as business practices and tools tend to be based on rationality rather than intuition. Practices to prepare the ground for an integrated intuition–rational approach should be planned and implemented at the beginning of or even before the FFE, and include activities like conversations and workshops aimed at activating business practitioners' creative and intuitive side. Another way to prepare the ground is to participate in promotional workshops where design practices and tools are showcased and experienced firsthand by the business practitioners. These workshops (commonly termed jams) are normally offered by design consultancy firms, but more and more often also by internal design departments attempting to promote their innovation approach to other departments. During these workshops, participants engage in the solution of a hypothetical case through design tools and methods. These cases could focus on problems of common interests (e.g., sustainability, community problems, personal health) or on company-specific problems if organized by internal design departments. Jams last three to four hours, take place at inspiring facilities, and involve 20 to 30 participants, including company owners and senior and middle managers. On the basis of these jams, business practitioners get a taste of what strategically collaborating with designers implies.

8.6 Conclusion

Design professionals are progressively establishing themselves as multifaceted and strategic sources of expertise for the FFE. Despite the growing number of companies integrating design professionals into the FFE, there is still limited knowledge on why and how to effectively implement such integration. In the previous sections, we elaborated on the “why” by showing how design professionals can use their practices and tools for addressing three key management challenges in the FFE. We also elaborated on the “how” by describing some key tactics, developed by both business practitioners and design professionals, for effectively integrating design practices and tools in the FFE. Our insights are summarized below:

- Design professionals can help solve key challenges in the FFE by means of specific design practices and tools listed in Figure 8.1.

- A critical step in the FFE is the appropriate formulation of the innovation challenge (problem definition). Designers can help to effectively take this step by reframing initial problem definitions and thinking holistically, using design tools such as mind mapping and metaphors.

- Management of information for reducing FFE uncertainty can also be addressed by involving design professionals. Relevant design practices include sensing future trends, brokering knowledge from different fields, and making information more graspable by translating, condensing, and animating it. Useful design tools to address the information management challenge are context mapping, customer journey mapping, and personas.

- The third key challenge in the FFE is getting and maintaining stakeholder support. Design professionals address this challenge by inspiring key stakeholders, by co-creating for maintaining stakeholders' commitment, and by aligning and integrating different stakeholder perspectives. Common design tools to help designers to get and maintain stakeholder support are storytelling, early prototyping, generative sessions, and stakeholder mapping.

- Routes by means of which business practitioners and design professionals can work together on a more strategic level in the FFE include, among other things, establishing long-term, trusting relationships; empathizing with each other's way of thinking and ways of working; and “preparing the ground” to undertake the FFE with an integrated intuition–rational approach.

It is important to emphasize that the full potential of integrating design practices and tools in the FFE is achieved only when design professionals and business practitioners see each other as innovation partners, recognizing and building on each other's strengths. Design tools and practices complement rather than replace business practitioners' tools and practices for addressing FFE challenges. Thus, reciprocal recognition of each other's contribution in the FFE of innovation is essential.

References

- Beckman, S. L., & Barry, M. (2009). Design and innovation through storytelling. International Journal of Innovation Science, 1(4), 151–160.

- Buzan, T. (1996). The mind map book: How to use radiant thinking to maximize your brain's untapped potential. New York, NY: Plume.

- Hey, J., Linsey, J., Agogino, A. M., & Wood, K. L. (2008). Analogies and metaphors in creative design. International Journal of Engineering Education, 24(2), 283.

- Koen, P. A., Bertels, H. M., & Kleinschmidt, E. J. (2014). Research-on-research: Managing the front end of innovation—Part II: Results from a three-year study. Research-Technology Management, 57(3), 25–35.

- Paton, B., & Dorst, K. (2011). Briefing and reframing: A situated practice. Design Studies, 32(6), 573–587.

- Pruitt, J., & Adlin, T. (2010). The persona lifecycle: Keeping people in mind throughout product design. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

- Reid, S. E., & De Brentani, U. (2004). The fuzzy front end of new product development for discontinuous innovations: A theoretical model. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21(3), 170–184.

- Sleeswijk Visser, F., van der Lugt, R., & Stappers, P. J. (2007). Sharing user experiences in the product innovation process: Participatory design needs participatory communication. Creativity and Innovation Management, 16(1), 35–45.

- Stickdorn, M., & Schneider, J. (2012). This is service design thinking. Amsterdam, Netherlands: BIS Publishing.

About the Authors

Giulia Calabretta is Assistant Professor in Strategic Value of Design at Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering, Delft University of Technology (Delft Netherlands). Giulia earned her PhD from ESADE Business School (Barcelona, Spain). Her research interests are in the area of innovation and design management. Currently, her research is focused on understanding how design skills and methods can be effectively integrated in the strategy and processes of companies, with a particular interest on the role of designers in innovation strategy and early development. Her research has been published in such journals as the Journal of Product Innovation Management, Journal of Business Ethics, and Journal of Service Management. Correspondence regarding this chapter can be directed to Delft University of Technology, Landbergstraat 15, Delft, Netherlands or [email protected].

Gerda Gemser is Full Professor of Business and Design at RMIT University of Technology and Design (Melbourne, Australia). Gerda earned her PhD degree at the Rotterdam School of Management (Netherlands). She has conducted different studies on the effects of design on company performance (in cooperation with the European governments and design association2015Sep18 093808s). She has held positions at different universities in the Netherlands, including Delft University of Technology and Erasmus University (Rotterdam School of Management). She has been a visiting scholar at the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania (United States), and Sauder School of Business, University of British Columbia (Canada). Her research is focused on management of innovation and design in particular. She has published in journals such as Organization Science, Organization Studies, Journal of Management, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Long Range Planning, and Design Studies. Correspondence regarding this chapter can be directed to College of Business, 445 Swanston Street, Melbourne VIC, Australia, or [email protected].