5

China and Southeast Asia: Offline Information Penetration and Suspicions of Online Hacking – Strategic Implications from a Singaporean Perspective

This is a most unusual chapter to compose, not the least because a Singaporean perspective is supposed to offer a window into China’s interactions with its geopolitical neighbourhood, Southeast Asia. Yet, there are compelling reasons for doing so. Singapore is, by most measures of global connectedness, a First World hub of trade, information and finance in Southeast Asia. Moreover, Sino-Singapore relations have gained unprecedented momentum on a political and ideological plane compared to its ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) neighbors. Finally, a small state perspective, such as Singapore’s, can be treated as a bellwether of security in its immediate “regional international society”. [CHO 06] A Singaporean perspective frames cybersecurity issues within a securitized frame of long term horizon forecasting, strategic anxiety and balanced appreciation of the political conditions of great and middle powers alike. In the area of cyber security, Singapore ranks amongst Asia’s top three most densely Internet penetrated national societies, with South Korea and Japan sharing the other two positions.

On the subject of Southeast Asia, it is proposed that China-Southeast Asia ties in relation to the cybersecurity sphere follow two strategic patterns. In the offline sphere, China’s foreign policy1 actively practises soft power in the realms of diplomacy, economics, educational and cultural exchanges. We must not ignore the historical dimension to this plane of interaction. Flows of Chinese migrants, emotional ties between the “motherland” population and the diaspora in Southeast Asia, and the nearly continuous solicitation of moral support and funds for the remaking of feudal China into the modern world of scientific industry and political rights for the population all depended upon the Chinese migrants domiciled in Southeast Asia. In the post-Cold War present, there are also nascent bonds built upon limited amounts of political and security collaboration on a state to state level. In this short chapter, I will briefly account for this soft power dimension because it exemplifies the perspective put forth by Martin Libicki where the “conquest” of online politics is assured by open front activities that gain the target populations favor through tangible initiatives that deliver physical welfare to those populations. As Libicki put it:

Lost in [the] clamour about the threat from hackers is another route to conquest in cyberspace, not through disruption and destruction but through seduction leading to asymmetric dependence. The seducer, for instance, could have an information system attractive enough to entice other individuals or institutions to interact with it by, for instance, exchanging information or being granted access. This exchange would be considered valuable; the value would be worth keeping. Over time, one side, typically the system owner, would enjoy more discretion and influence over the relationship, with the other side becoming increasingly dependent. Sometimes the victim has cause to regret entering the relationship; sometimes all the victim regrets is not receiving its fair share of the joint benefits. But if the “friendly” conquest is successful, the conqueror is clearly even better off.2

This is soft power as foreign aid, and foreign aid becomes associated synonymously with a “good community” that acts as a generous and humane donor. [CHO 07] [NYE 04]. It is expected that if efficaciously delivered, such foreign aid engenders a positive predisposition to open information operations conducted by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in foreign territories since the PRC will be theoretically viewed by the foreign publics as a non-hostile intervener in local political economy. In fact, if we treat China’s information penetration as legitimate interventions in political economy, there is no “politicizable” issue with the PRC’s open intelligence gathering until some egregious violation is broached in the mainstream media. China’s information penetration is assumed to be synonymous with what I have termed “information operations”, which refers to that entire range of symbolic resources straddling both military and civilian spheres that are aimed at achieving national objectives in both peacetime and wartime [CHO 13].

In the online sphere, China-Southeast Asia ties register comparable levels of public concern with hacking, cyber vandalism and online information theft. While this has evolved into a matter of high political significance on the plane of Sino-US and Sino-EU relations, it must be borne in mind that the responses of Southeast Asian citizens and governments are divided by the goodwill generated in the offline sphere of practical soft power delivery by both the Chinese government and its citizens. Moreover, Southeast Asian netizens have also demonstrated in recent years a number of potential retaliatory capabilities in the online sphere from virus launching to the spontaneous articulation of disapproval of Chinese actions through blogs, Facebook and Twitter. Figure 5.1 summarizes the two-pronged organization of this chapter.

Figure 5.1. Interactions between Offline and Online Predispositions towards Chinese Information Penetration

The remainder of this chapter will thus devote considerable attention to how the People’s Republic of China enjoys the latent offline privilege of tapping into an intricately large information resource that is the overseas Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, and augmenting this resource with the formal deployment of soft power at the government-to-government and bilateral corporate levels. Offline information power is relevant in relation to comprehending the Chinese interpenetration of Southeast Asian states and societies since it fleshes out Libicki’s thesis about the openly “seductive” dimension of the conquest of cyber spatial interactions. Online interactions between Chinese government proxies, spontaneous netizens and their counterparts in Southeast Asia do exist, except that they are not widely founded upon hard incontrovertible evidence, resembling instead much of the ephemerality and intangibility of cyberspace derived community. After probing both offline and online planes of China-Southeast Asia interactions, the chapter will conclude by calling attention to the need to frame research on China’s so-called cyber-threat potential to Southeast Asia and the world in a more nuanced manner that takes into account other dimensions of Chinese information power rather than just cybersecurity or cyberwar potential.

5.1. Offline sphere: latent “diasporic” information power and official Chinese soft power

The starting point of discussing Chinese soft power in relation to China-Southeast Asia relations must begin with treating the Chinese diaspora in the Southeast Asian region as a large networked mechanism of information exchange. It may serve as a latent power extension for Chinese foreign policy and national security interests overseas. It might also serve as a network of divided loyalties and contradictory emotions that frustrates Chinese official policy implementation. A diaspora is commonly understood to be a collection of persons identifying with a particular ethnicity, religion or nationality who are domiciled outside their territories of ancestral or legal origin for reasons of work, physical displacement arising from natural calamities, or of matters of political conscience. In this regard, as Leo Suryadinata observes, the phrase used to describe the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia, “Overseas Chinese”, “has been used to refer to both Chinese nationals overseas and ethnic Chinese who are citizens of other countries. It also has the connotation that the Chinese are sojourners who will eventually ‘return’ to China”. Moreover, “the term, often regarded as the English equivalent of a Chinese term huaqiao (Chinese sojourners), had been used before the problem of nationality arose during which the boundaries between Chinese overseas and local citizens were not clearly drawn”3. For the purposes of my argument, the “overseas Chinese” pose two implications. Firstly, Chineseness may be regarded as a state of mind and action regardless of one’s physical domicile. Therefore, it is common to find the Chinese diaspora frequently referring to their cultural kin across Southeast Asia and those living in China itself for reaffirmation of cultural rituals, educational exchanges and exercises in linguistic proficiency.4 Cultural Chineseness, as manifested in language immersion programmes, consumption of food and audio-visual popular programming and so on, reveal a thick volume of symbolic exchanges to reaffirm a common bedrock of cultural identity. Secondly, this also implies that persons identifying with the idea of cultural Chineseness would have developed either formal or informal networks of interaction whereby one segment of the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia may refer to another segment for expressions of moral, cultural or material support on the basis of retaining their collective cultural Chineseness. All these offline interactive features are relevant as information power features since they offer China a means of disseminating particular views about cultural authenticity, ideological correctness or variation, or simply articulating the parameters of Chinese patriotism.5 In some ways, this is the phenomenon identified by Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan as the “tribalism” in communication facilitated by an electronically networked “global village”: “it helps to know that civilization is entirely the product of phonetic literacy, and as it dissolves with the electronic revolution, we rediscover a tribal, integral awareness that manifests itself in a complete shift in our sensory lives”6. Therefore, by logical extrapolation, the diaspora offers a very appropriate milieu through which the “open conquest” of cyberspace occurs through the seductive appeal of affirming and re-affirming a common culture. However, we must also bear in mind that this diasporic information resource may be a fickle one subject to the contingencies of political and historical currents. Completing his study in 1985, Leo Suryadinata warns that:

Southeast Asian nations, especially ASEAN, are still at the nation-building stage. Southeast Asian governments have adopted various measures in order to form their “national identity”. Ethnic Chinese minorities have been quite responsive to these measures and the Southeast-Asianization of ethnic Chinese in this region will continue. The process is by no means smooth, especially in some countries where the government requires complete eradication of “Chineseness”.

With the exception of Indochina, many Chinese in Southeast Asia have been aware that their prosperity and safety depend largely on the local authorities rather than on Beijing or Taipei. This is especially so with Taipei which has no power to give meaningful protection to the ethnic Chinese.7

As a manifestation of this local Southeast Asian appreciation of the political correctness of “sanitizing” cultural Chineseness in relation to Beijing’s potential diasporic network power, prominent local businesspeople in Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines, Vietnam and Cambodia have adopted names according to the indigenous national language, or have stylized their spellings to accord with local customs. It is a well-known fact that any form of ethnic Chinese deviation from local Southeast Asian nationbuilding projects would trigger either orchestrated reprisals in the form of the imposition of extremely discriminatory national policies, or organized rioting against Chinese persons and property in the urban areas, with the rare exception of Singapore, a state where ethnic Chinese form a clear majority. The reprisal scenario proved to be the reality in Indonesia under President Suharto in the 1980s, and post-unification Vietnam in the 1970s. Post-independence Malaysian politics have always witnessed the playing of “the Chinese card” by Malay Muslim politicians to win votes. On several occasions in the 1960s, this baiting of the Chinese boiled over into riots in Malaysia, consequently provoking the introduction of legislation to curb Chinese political and economic ambitions. As a result, ethnic Chinese businessmen in Malaysia and Indonesia have been visibly supportive of their governments’ policies towards trade and investments with the PRC, and have commensurately aligned their political views in tandem with their governments postures towards China during the Cold War, after the Cold War, and on the occasion of the many rows over human rights practices between China and ASEAN on the same side, and the USA and EU on the other, in the 1990s and beyond. During the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998, anti-Chinese looting and rioting in a few Indonesian cities drew verbal condemnation from Beijing. Reciprocally, and quietly, ethnic Chinese businessmen in Southeast Asia have welcomed China’s ascent as an economic powerhouse, notwithstanding the occasional social frictions between the PRC Chinese understanding of managed free enterprise economics and the more laissez faire, efficiency-driven, and market-friendly mindset of the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. It was no surprise that the Chinese in Southeast Asia have steadily supported Beijing’s image burnishing efforts in the staging of the 2008 Olympics in the Chinese capital, and quietly shared Chinese netizens outrage at the 1999 “accidental” bombing of the PRC embassy in Serbia during NATO’s humanitarian war in Kosovo [FUL 08]. Since the Deng Xiaoping reforms stemming from 1978, the PRC has especially courted Southeast Asia’s ethnic Chinese businesspeople to invest in the “mother country”.

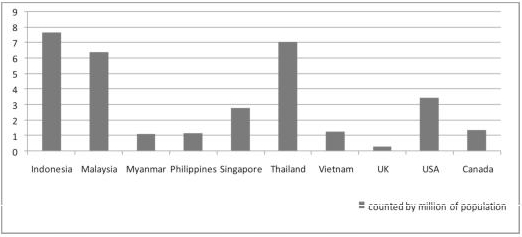

Therefore, we might argue that the reliability of the Chinese diaspora as the PRC’s information platform is a “half empty, half full” proposition, but the numbers of the diaspora, insofar as we count points of opinion as virtual ammunition in a war of public opinion in the era of global information flow, is considerable should the elites in Beijing attempt to cultivate it for foreign policy and national security purposes. Figure 5.2 provides a simple illustration of the number of “potential” pro-Beijing opinion points, sympathy conduits, and informal cyber “gendarmes” if Beijing can convert them to its side on any given issue. The statistics also reveal that the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asian states is more numerous than those resident in the major western states such as Canada, the US and the UK. This may incidentally be construed to mean that Beijing may even dispense with cyberhacking as a means of ferreting valuable information from Southeast Asia, given the possibility of recruiting and mobilizing conventional spies. Conversely, if we take Libicki’s arguments about the open

conquest of cyberspace seriously, then the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia might also be tapped as a resource available for infiltrating western centers of high technology. This can only happen if, and only if, Beijing’s strategic planners can convert them into patriotic agents for its national security given the diaspora’s dilatory relations with the central government in Beijing.

Figure 5.2. The Chinese Diaspora in Southeast Asia Compared to the UK, USA and Canada. Source: [TEC 11]

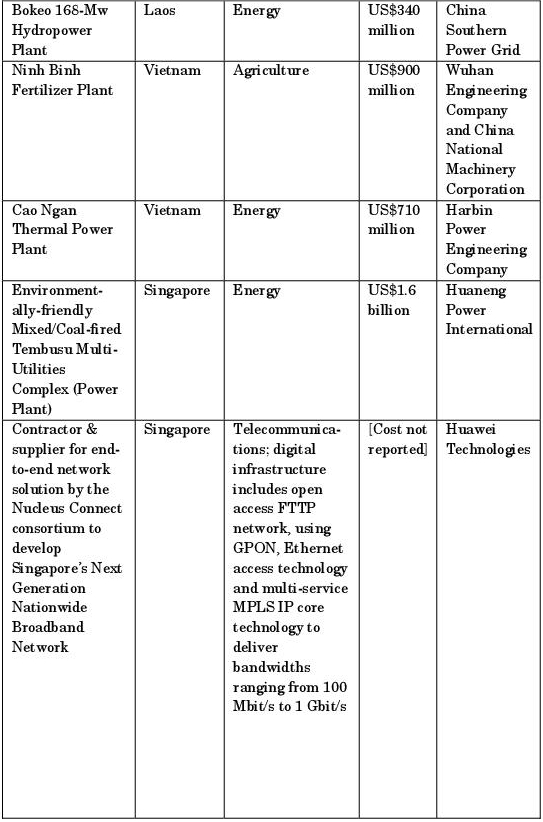

On the official level, Chinese soft power is an essentially post-Mao policy departure. During the Cold War, Chinese economic power overseas was thwarted by communist-inspired dogmatism at home and foreign policy abroad. China tried to employ networks of Chinese culture and education, such as cultural troupes, party officials and overseas Chinese medium universities in Southeast Asia, to act as proxies for spreading Maoist style revolution. This damaged China’s soft power for decades. It was only with the advent of Deng Xiaoping’s modernization programmes at home that foreign policy began to be re-aligned to support domestic development priorities. Having been made aware that Chinese political, diplomatic and cultural soft power towards Southeast Asia was tarnished by Beijing’s Cold War strategies, the new leadership replaced their Southeast Asia policy from the mid-1980s with foreign economic policy instead.8 While Beijing initially welcomed trade and investment from the newly industrializing economies of Southeast Asia, from mainly Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, the flow of trade and investment from the PRC to these countries equalized by the mid-1990s. China began to officially formulate aid packages for the reformist communist governments in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, and sought to offer foreign direct investment in the rest of the ASEAN economies on a win-win basis. China in turn needed alternative oil, gas and other energy supplies from Southeast Asia.9 Finally, it was perceived that China’s military and diplomatic interests could not be treated separately from the pursuit of a good neighbour policy towards Southeast Asia. Since 2005, ASEAN has emerged as China’s fourth largest trading partner after the EU, the US and Japan. China had in turn attained in 2005 the position of being ASEAN’s sixth largest trading partner.10 Since 2011, ASEAN has become China’s third largest trading partner, with forecasts by Chinese observers predicting that the number one position awaits in 2015 [BAO 12]. One way of viewing the size of Chinese soft power investments in Southeast Asia is to highlight a sample of its headline-making investments, as seen in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1. The PRC’s Key Infrastructure Projects and Investments (1990-2013)11

While this list should be regarded as a mere snapshot of the entrenched nature of Chinese soft power in Southeast Asia, and hence not necessarily exhaustive, a number of strategic implications can be drawn in relation to cybersecurity in Southeast Asian national contexts. Firstly, Chinese state-linked companies and government departments enjoy direct access to the blueprints for the electrical, digital and electro-mechanical control systems of these infrastructure projects since the former are either the creators or collaborators in the design of infrastructure. This significantly eliminates the costs associated with disabling a potential adversary’s infrastructure if the need arose in the context of acute hostility between the PRC and an ASEAN state. Secondly, a technological and infrastructural interdependence has arisen between local infrastructure users, governments and Chinese state-owned firms. Local users in Southeast Asia depend upon either Chinese training or Chinese maintenance. Local job creation by these infrastructural projects also engenders interdependence by way of skill transfers, and possibly, some degree of indirect and direct salary payments. And thirdly, the very threat of Chinese technical withdrawal during the partial completion and post-completion phases may be credible in inducing China’s Southeast Asian collaborators to play ball with existing projects. Ultimately, it must surely be understood by all parties to these infrastructural projects that all modern infrastructure, including “brick and mortar” categories like power plants, optical fiber cables, steel factories and refining complexes, are heavily reliant upon IT circuits and their associated software. This creates cyber vulnerabilities for China’s possible exploitation if relations turn hostile bilaterally. The telecommunications infrastructural projects in Indonesia, Laos and Singapore are the most prominent objects of the PRC’s cyber “conquest” of Southeast Asia since the latter produced, either in whole or in part, the blueprints for digital connectivity. This digital infrastructure is almost always of a dual-use nature, offering both benign and malevolent possibilities for the PRC’s long distance penetration, and should it be needed, sabotage. To date, neither ASEAN nor the PRC have even remotely speculated on these dark scenarios, despite the occasional public brushes with allegations of electronic espionage conducted by the US and its collaborators within Southeast Asia that were unveiled by the disclosures of the American fugitive spy Edward Snowden from his refuge in Russia in 2013.

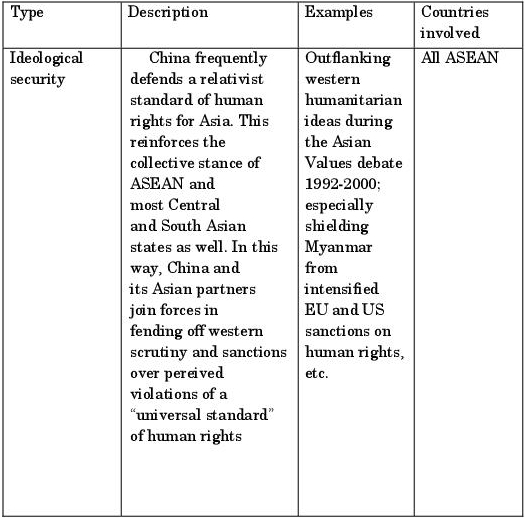

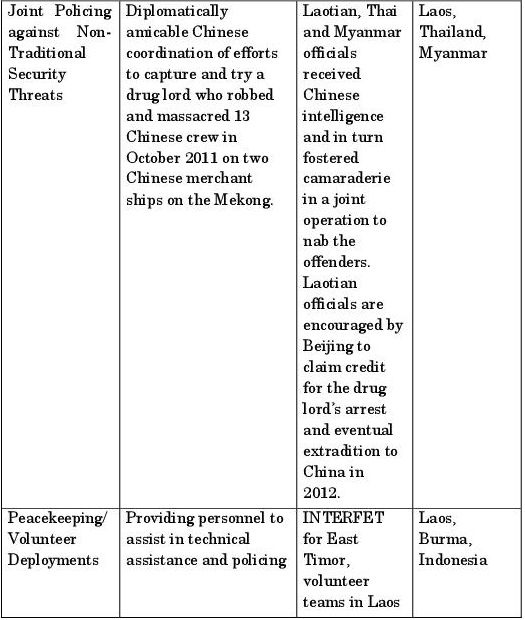

On the political and diplomatic front, the PRC has carefully avoided the ideological approach of the Cold War. Since the 1980s, Chinese diplomacy and security approaches to Southeast Asia have struck a pragmatic, neoliberal and functionalist tone, notwithstanding the unresolved disputes with ASEAN over the South China Sea (i.e. the Spratly and Paracel Islands) [HAA 05]. Table 5.2 summarizes the highlights of the PRC’s current pragmatic soft power diplomacy.

Table 5.2. Elements of China’s Soft Power Diplomacy and Security Confidence-Building Strategy (1990-2013)12

A number of implications can therefore be drawn from this spate of soft power diplomacy. Firstly, the PRC is clearly manifesting a “charm offensive” by portraying itself as a practical, non-ideological partner of Southeast Asian states. Secondly, China is treating Southeast Asia as a demonstration zone for proving its claim to be a “peacefully emerging” responsible great power. This carefully cultivated image has been partially dented by the recent 2010-14 flare-up of the unresolved confrontation between China and its Southeast Asian neighbors over conflicting claims on the Spratly Islands. This heightening of maritime tensions between the Philippines and China cast a shadow over the Chinese response to the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan which struck a large swath of the central Philippines in November 2013. Beijing’s initial offer of US$100,000 in humanitarian aid was widely mocked in regional and international media even though it upped the amount to US$1.6 million within days. In comparison, Britain announced more than US$32 million, the US with US$20 million, and Japan with US$10 million [JAC 13]. Nonetheless, the overlapping patterns of pragmatic functionalist cooperation remain in place. Southeast Asian states do rely on Chinese cooperation in combating transnational corporate, maritime and financial crimes. Southeast Asian states also welcome China as a source of food imports as a substitute for inadequate homegrown produce. Moreover, China-ASEAN industrial zones offer complementary advantages for both their own MNCs and third party MNCs for co-locating manufacturing, research and development, and headquartering activities. China is therefore likely to be perceived as both a soft aid giver, and a practical partner in development. Thirdly, and finally, ASEAN states value a Chinese political and economic presence in the region as a buffer, or fallback, in the event of the political retreat of, or frictions with, western powers. China’s growing political heft makes it an unspoken counterweight to American unilateralism on a variety of matters, especially on human rights and technology transfer. For these reasons, China’s offline diplomatic activism pre-empts somewhat any notion of the PRC as a cyber threat of the first order.

5.2. The online sphere: hacktivism as mostly projections

Chinese cyber-attacks within or targeting Southeast Asian societies are not well documented, but this does not mean that they do not exist. One Philippine academic has nonetheless documented a highly suspected PRC-sponsored cyber-attack on the University of Philippines website on 20 April 2012, whereupon the University’s site was defaced. The next day, Filipino netizens affiliated with “Anonymous Philippines” retaliated against selected PRC websites.13 In Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, there are reported instances of commercially targeted cyber-attacks on a frequent basis but there has been no direct attribution to the Chinese. In keeping with the carefully hedged analysis of this chapter, this author can therefore mostly project Southeast Asian capabilities vis-à-vis potential and actual Chinese doctrines.

To begin with, Southeast Asian cyberactivism can be traced to the following activities. Firstly, there is widespread evidence of nationalist cyber retaliation through blogging, Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites.14 This phenomenon tracks the offline nationalistic sensitivities between Southeast Asian peoples whenever territorial claims are openly debated, or public slights are perceived by either side in any politicized issue ranging from food culture, to economic inequities between states, to personal blogs about a host society’s discrimination against foreign students, to providing succour to unpopular dissidents from another state. This habit of protest and complaint increasingly takes on racist tones as online spats between Singapore and Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia and Sino-Singapore people-to-people ties demonstrate in recent years [TEA 12]. Netizens, who are mostly within the 16-49 age category, are quick to take umbrage at national losses of “face” and to manifest it even before their respective foreign ministries produce an official reaction. On their part, Chinese bloggers active on their domestic Twitter and Facebook-like sites weibo and sina.com are also not reticent when it comes to polishing China’s image overseas, especially if it requires intervention on third party hosted pages [TSO 13].

Secondly, some Southeast Asian states have on their statute books strict laws against sedition, propaganda actions contrary to public order, libel against sitting Heads of State and acts of lèse majesté. Thailand has been at the forefront of efforts to curb access to YouTube on the grounds of certain uploaded videos being deemed insulting to the Thai monarch. In the wake of the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis, Malaysia has instituted a net patrol unit to trawl Malaysian websites for seditious material assessed to be prejudicing economic recovery and regime stability. Ever since the Web arrived in Singapore, the government has practised strict vigilance against libellous comments against the sitting Cabinet members of the ruling party and launched legal actions against posters of racist commentary. It was only in 2011 that a ban on political campaign videos was lifted to facilitate “Internet-era” elections. Although it was not stated officially, the Barack Obama Internet election campaign of 2008 may have converted some officials in Singapore. Even freewheeling, democratic India had seen fit to take a leaf from Southeast Asian practice in August 2012 to force the closure of 245 websites that featured doctored visual media fanning anti-Muslim riots in the north-eastern parts of the country. On that occasion, India formally pressured Google, Facebook and Twitter to aid in censorship for the sake of public order and social harmony [BAJ 12].

Thirdly, the boom in Facebook, Twitter and online shopping membership and activities in Southeast Asia have fostered national online civil societies that occasionally prove rambunctious and independent of their sovereign governments wishes. This “safety valve” allows dissent to flourish where offline political spaces are closed. This is the case across all of Southeast Asia. Online shopping itself generates a new sphere of consumerist loyalty that transcends national borders and may indirectly facilitate liberal “contamination” from the western consumer centres in the G7 economies. For instance, it is difficult to avert your gaze while shopping for iPads, fashionable garments, books and bags online while Amnesty International or Oxfam flashes paid advertisements promoting particular causes at the top of your shopping page, and some of these causes may well be endorsed by leading music and fashion celebrities, thereby subtly augmenting transnational cultural and ideological “contamination” from the perspective of sovereign authorities.

Finally, it needs to be noted that available academic and quasi-academic literature on Chinese cyberconflict doctrine produced in Southeast Asia tends to track western interpretations of Chinese capabilities and intentions with few exceptions. One Filipino assessment described Chinese cyber-strategy as largely manifesting low impact cyberconflict (LICC) with reference to the fact that the Chinese officialdom can wage “quiet war” or “retaliation” with impunity since the electronic consequences are mostly ephemeral with no loss of lives involved. This Filipino observer described LICC as “cases of cyber conflicts that are aimed towards influencing or shaping public opinion within the target state” and cites a Chinese military author as stating that LICC is akin to metaphorically forcing a cat to consume hot pepper whereby the most subtle and least painful method is to “ground the pepper up and spread it on his [the cat’s] back, which makes the cat lick himself and receive the satisfaction of cleaning up the pepper”15. The relative difficulty in confirming the identity of the source of a cyber-attack allows, in some Southeast Asian perceptions, Chinese hackers to get away with officially-sanctioned retaliation. This author’s own reading of the few Chinese tracts on cyberconflict strategy online supports the view that the People’s Liberation Army may be strategically avoiding an over-obsession with techno-electronic warfare aspects of waging cyberconflict in favor of amplifying its propagandistic aspects [PRC 08] [WAN 03]. The more important priority in a holistic conflict strategy is to seed doubt in the enemy’s mind and then defeat him without physical combat, or at the very least, with the minimal clash of arms. This is an assessment also congruent with the author’s own reading of Sun Tzu, Mao Zedong and Vo Nguyen Giap in establishing an Asian perspective on information operations [CHO 13]. online sphere seems to reveal an environment of latent threat potential from Chinese cyber capabilities but these largely remain projections in the absence of mounting evidence of Chinese cyber-attacks in the region. What is probably of more concern in the Southeast Asian cyberconflict arena is the pattern of nationalistic and inward-oriented possibilities for causing bilateral and domestic mischief against a developing nation’s social harmony. The key to reading China-Southeast Asian cyber interactions has to lie mostly in performing offline sociological and political trend analysis for now. Therefore, the jury is either out on China’s cyber threat to Southeast Asia, or the Chinese have taken to heart Libicki’s thesis of openly propagated conquest of cyberspace through offline and online measures; or thirdly, and perhaps more culturally, the Chinese have adhered to the best parts of their strategic culture to wage conflict short of physical war through information operations.

5.3. Conclusion: offline politics strategically obscure online projections

In the light of present trends, circa 2014, we cannot conclude that the PRC poses a cyber threat to Southeast Asia in a definitive manner. The gains of Chinese soft power in the offline sphere ensure that China remains in the public eye of Southeast Asian societies as a mostly pragmatic partner in development and security confidence building. Nonetheless, there are possibilities that Chinese investments in Southeast Asian infrastructure and in the loyalties of the Chinese diaspora, may presage a more aggressive cyber strategy in the indeterminate future. The

5.4. Bibliography

[BAJ 12] BAJAJ V., “Internet Analysts Question India’s Efforts to Stem Panic”, International New York Times, August 21, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/22/business/global/internet-analysts-question-indias-efforts-to-stem-panic.html?adxnnl=1& adxnnlx=1392026755-BVU3UB/jIw8quv1vQWUqVQ (acces.sed)

[BAO 12] BAO CHANG., “ASEAN, China to become top trade partners”, chinadaily.com.cn, April 20, 2012. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2012-04/20/content_1509 4898.html.

[CHA 13] CHANG A., Beijing and the Chinese Diaspora in Southeast Asia: To Serve the People, NBR Special Report #43, Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, pp. 1–30, 2013.

[CHO 04] CHONG A., “Singaporean foreign policy and the Asian Values Debate, 1992–2000: reflections on an Experiment in Soft Power”, The Pacific Review 17, pp. 95–133, 2004.

[CHO 06] CHONG A., “Singapore’s foreign policy beliefs as “Abridged Realism”: liberal and pragmatic prefixes in the foreign policy thought of Rajaratnam, Lee, Koh and Mahbubani”, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific 6, pp.269–306, 2006.

[CHO 07] CHONG A., Foreign Policy in Global Information Space: Actualizing Soft Power, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

[CHO 13] CHONG A., “Information Warfare? The Case for an Asian Perspective on Information Operations”, Armed Forces and Society, pp. 1–26, 2013.

[EKH 09] EK HENG, “Indonesia sizzles as market for China’s telecom equipment makers; Huawei and ZTE Corp are integral to country’s telecom sector”, Telecommunications International (TCIN), December 24, 2009.

[FUL 08] FULLILOVE M., “Chinese Diaspora Carries Torch for Old Country”, Financial Times, May 19, 2008.

[GOM 13] GOMEZ M.A.N., Awaken the Cyber Dragon: China’s Cyber Strategy and its Impact on ASEAN, 2013.

[HAA 05] HAACKE J., “The Significance of Beijing’s Bilateral Relations: Looking “Below” the Regional Level in China– ASEAN ties”, in HO K.L., KU S.Y.C., China and Southeast Asia: Global Changes and Regional Challenges, pp.111–327, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 2005.

[HAY 12] HAYS J., “Dispute Between China And Vietnam Over The Spratly Islands And South China Sea”, FACTS AND DETAILS, 2012. http://factsanddetails.com/china/cat8/sub52/item1902.html.

[HPI 13] HUANENG POWER INTERNATIONAL INC., “Huaneng Power International, Inc. Announces Operating Results for 2012”, Press Release – The Wall Street Journal – Asia Edition, March 19, 2013. http://online.wsj.com/article/PR-CO-20130319-912822.html.

[JAC 13] JACOBS A., “Rivalries play a Role in Typhoon Aid”, International New York Times, November 16–17, 2013.

[LIB 07] LIBICKI, M.C., Conquest in Cybersapce: National Security and Information Warfare, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

[MCL 68] MCLUHAN M., FIORE Q., War and Peace in the Global Village, Bantam Books, New York, 1968.

[NYE 04] NYE Jr. J.S., Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics, New York, Public Affairs, New York, 2004.

[OND 09] OPTICAL NETWORKS DAILY, “Huawei wins Singapore Next Gen NBN end-to-end network solution contract + expands CDB credit line to $30bn”, OBSERV, September 24, 2009.

[PAR 10] PARAMESWARAN P., “Measuring the Dragon’s Reach: Quantifying China’s Influence in Southeast Asia (1990-2007)”, The Monitor: Journal of International Studies (College of William and Mary, USA) 15, pp. 37–53, 2010.

[PLN 06] PEOPLE’S LIBERATION ARMY NAVY (PLN) WANG P-J et al., A Publication of the PLA Navy Dalian War Studies Institute, 2006, paper no.116018. [Author’s translation].

[RAM 13] RAMASAMY M., “China, Malaysia Plan $3.4 Billion Industrial Park in Kuantan”, Bloomberg News. February 5, 2013. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-05/china-malaysia-plan-3-4-billion-industrial-park-in-kuantan.html.

[SCH 08] SCHMIDT J.D., “China’s Soft Power Diplomacy in Southeast Asia”, The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies 26, pp. 22–49, 2008.

[SUR 85] SURYADINATA L., China and the ASEAN States: The Ethnic Chinese Dimension, Singapore University Press, 1985.

[TEA 12] TEMASEK TIMES, “Majority of Singaporeans want NUS PRC scholar Sun Xu’s MOE scholarship to be revoked”, The Temasek Times, February 25, 2012. http://temasektimes. wordpress.com/2012/02/25/majority-of-singaporeans-want-nus-prc-scholar-sun-xus-moe-scholarship-to-be-revoked.

[TEC 11] THE ECONOMIST, “Diasporas – Mapping Migration”, The Economist Online, November 17, 2011. http://www.economist. com/blogs/dailychart/2011/11/diasporas.

[TSO 13] TSOI G., “Edit Wars” on Wikipedia over China topics”, International New York Times, October 28, 2013: 16.

[WAN 03] WANG V.W.-C., “China’s Information Warfare Discourse: Implications for Asymmetric Conflict in the Taiwan Strait”, Issues and Studies vol. 39, pp. 107–143, 2003.

[XIN 13] XINHUA NEWS AGENCY, “Chinese company donates computers to bolster Lao cyber security”, Xinhua Electronic News (XHELEN), December 2, 2013.

1 I will treat “China” and its legal name the “People’s Republic of China”, or “PRC”, synonymously as the same nation-state. The descriptor “Chinese” may occasionally refer to the cultural nation of persons of Chinese ethnicity regardless of domicile, such as in reference to the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia.

2 [LIB 07] p. 3. Italics mine.

3 [SUR 85] p. 1.

4 [CHA 13] pp. 2–6.

5 [CHA 13] pp. 15–18.

6 [MCL 68] pp. 24–25.

7 [SUR 85] p. 23.

8 [HAA 05] pp. 112–115.

9 [SCH 08]; [CHA 13] pp. 7–13.

10 [SCH 08] p. 28.

11 The bulk of this table was provided by Prashanth Parameswaran’s published research article, especially Table 4.7 [PAR 10] pp. 43–44; also [HPI 13]; [OND 09]; [RAM 13]; [EKH 09]; [XIN 13].

12 Information derived mostly from Table 4.12 of Parameswaran’s 2010 study ([PAR 10] pp. 49–50) and updated by the author of this chapter based upon his own research [CHO 04].

13 [GOM 13] p. 256.

14 See for instance the evidence of Vietnamese bloggers retaliating against Chinese aggression in a third party online report at [HAY 12].

15 [GOM 13] pp. 254–255.