6

Impact of Mongolia’s Choices in International Politics on Cybersecurity

Mongolia is a very special nation in at least two respects: its geographical position, sandwiched between two giants on the international scene and in cyberspace – i.e. Russia and China, its two bordering states; the political choices made by the authorities, which have committed Mongolia to a process of coming closer to the Western world, in order to attempt to find a third channel, complementary to its dependence on Russia and China. In this context, faced with two major powers which have a far greater mastery of cyberspace – if only because of the existing networking infrastructures, the number of connections, number of Internet users, national industries – what possible pretentions could a modest-sized state have in that same cyberspace? Is it not totally subjugated to the pressure from its neighbors? Is it possible for it to develop independently, freely, and enforce its own sovereignty? Is that sovereignty not threatened by the cyber-operations likely to be carried out against it by the major powers? Is cyberspace really that space of emancipation, with a level playing field, which would enable actors with modest capacities to assert their own ambitions? Indeed, what weight could a modest-sized cyberspace hold in the evolution of a state’s society, its economy, its international relations and its security and defense policies? What role can a state with only a modest cyberspace hope to play in the global cyberspace? In this chapter, we intend to look at the way in which cyberspace is changing in the relations between China and Mongolia.

6.1. Mongolia’s cyberspace

Since the mid-1990s, the telecommunications sector has been reformed, partially privatized for landlines (the historical operator being Mongolia Telecom), and opened for competition for landlines and mobile telephony. The mobile telephony market has experienced major and rapid growth. In 2005-2006, two new mobile telephony licenses were granted to Unitel (for GSM) and G-Mobile (CDMA)1, which now share the mobile telephony market with Skytel and Mobicom Corporation. Three WLL (Wireless Local Loop) operators offer mobile coverage of the entire territory for telecoms services: Skytel, Mobicom and Mongolia Telecom Company. In a country where the population is nomadic, and disseminated over a truly vast territory, with few hardwired telecom infrastructures, mobile telephony has become popular. The penetration rate of mobile telephony is now higher than 100% (3.375 million mobile telephones in 2012).2 The growth of the Internet amongst the population is greatly constrained by the peculiarities of the situation (large territory, low population density). On a geographic level, the country has a surface area of around 1.6 million km2, and a population of 2.7 million inhabitants. The country shares a 3543 km border with Russia, to the north, and 4677 km boarder with China to the south.3 The population is made up of a 95% Mongol ethnic group, with the rest being Turks, Chinese and Russians.4 The population is identified both as Buddhist and nomadic.5

Table 6.1.Evolution of the population of Internet users. Table constructed from data published by the ITU8

A study9 of the social media (such as Voodoo.mn and Biznetwork.mn, both set up in 2009) indicates that as yet, they are not widely used by Mongolia’s populace. The most widely used social networks are based abroad (e.g. Hi5.com and Facebook). Also, the high rate of use of Facebook makes Mongolia an exception in comparison to its two neighbors, which tend to use national solutions instead (VKontakte for Russia and Qzone for China).10

6.2. Cyberspace and political stakes

6.2.1. Mongolia targeted by cyber-attacks

The first cyber-attack in Mongolia seems to have recorded in 1995.11 Since then, although the networks are as yet modestly developed, and the case of cyber-attacks are not widely referenced and documented (notably because of the absence of any national legislational framework sanctioning computer pirating12), the country’s networks have been subjected to cyber-attacks. We can cite a few examples, such as the attacks (essentially website defacements) of servers in the government, in banks, in education.13 For example, the national police website (police.gov.mn) was defaced on 18 February 2013 by the “Viru$ No!r”, apparently as part of the “Op Myanmar” operation.

Mongolia was among the 60 countries affected by the “Lurid Down Loader” attack14 revealed in September 2011.

The website of the Mongolian Liberal Union Party suffered service denial attacks between 10 and 16 May 2012.15 Those responsible for the attacks originating abroad have not been caught.

Figure 6.1. Defacement of the national police website, 18 February 2013 by Viru$ No!r

Figure 6.2. Defacement of the Mongolian Liberal Union Party website16

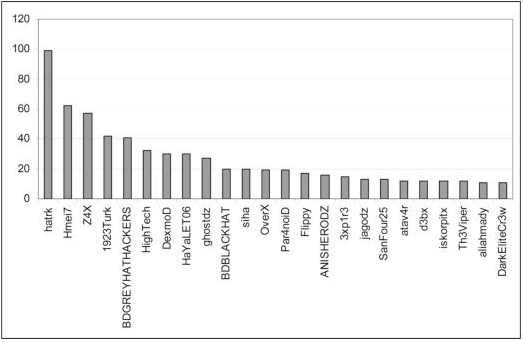

Figure 6.3. Number of Mongolian websites defaced by each hacktivist signature, over the period from 8 June 2011 to 21 April 2014. Statistics established using data published on zone-h.org

Over the period 8 June 2011 to 21 April 2014, the number of defacements of Mongolian websites, cataloged in the database zone-h.org, was 1250. The main signatures used were HaTRk (accounting for 26,674 website defacements to date by 23 April 2014); Hmei7 (264,000 defacements to his/her/their name); Z4X (171 defacements); 1923Turk (265,897 defacements); and BDGREYHATHACKERS (53024 defacements). These actors are not specifically targeting Mongolia’s sites. Most .mn sites defaced are on Linux servers.

Figure 6.4.Operating systems of the servers hosting the sites which have been defaced on the .mn domain over the period 8 June 2011 to 21 April 2014 (from the zone-h.org database)

One of the reasons for the recent cyber-attacks suffered by Mongolia may lie in its changing place on the international chessboard, formalized by the opening up of the country to the West, thanks to the political willingness displayed by the government.

In 2011, Mongolia celebrated the 100th anniversary of its independence. In 1911, Mongolia was keeping its distance from China, before coming under Soviet control in 1924 (it was considered to be the “6th republic of the USSR”). On the political level, the fall of the communist empire gave way to a government of “communist” obedience, thus ensuring

continuity during the transition.17 The country was governed by a communist regime, and then became a parliamentary democracy. When the Soviet Empire collapsed, Mongolia turned toward the Western democracies. It also began the process of development of its telecoms infrastructures.

The choice was made to forge closer links with the United States and the EU (but also Japan and other states) and break away from the lone influence of Russia and China – two giants on the international stage between which Mongolia is geographically pincered. In the 2000s, the ex-communist elites turned toward models of the market economy, toward America and Asia, i.e. new liberal democratic ideals.

The evolution of Mongolia’s international position can be expressed in a variety of ways. Notable examples include:

– participation in joint military exercises, particularly with the United States: Khaan Quest 2013 (the 2014 exercise included participation from China);

– the signing of international agreements such as that linking Mongolia with the State of Alaska – more specifically the Alaska National Guard, as part of the National Guard Bureau’s State Partnership Program, from 2003 onward.18 Cybersecurity is one of the areas in which this exchange takes place;

– the increasing closeness to the EU can be traced back to 1989. An accord was signed with the EU in April 2013, relating to political dialog, trade, aid to development, cooperation in the domains of agriculture, energy, climate change, research and innovation, education and culture;19

– the “Electro Mongolia” (Tsakhim Mongol) program designed to develop ICT in the country has benefited from the support of foreign countries and international organizations20: South Korea contributing to the setting up of e-governance, the World Bank (which has been providing assistance since 2005)21 and the Asian Development Bank22 to the development of networks in rural areas, etc.;

– Germany has been one of the most active European partners in the aid given to Mongolia since 1991, particularly in terms of developing its telecommunications;23

– the European Union has permanent representation in Mongolia.24 The action of the European Union and the finance from the assistance program go towards the diffusion in Mongolia of the norms and values held by Western society: democracy, human rights, environmentally sustainable development, equal access to healthcare, to education, social cohesion, defense of the most vulnerable, etc.;

– in terms of defense, NATO and Mongolia agreed on a cooperation program in March 2012.25 Mongolia contributed to the operations in Afghanistan as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF).

However, even with the proliferation of these exchanges, Mongolia is still heavily dependent on China: in 2007 almost 72% of Mongolia’s exports went to China26; by 2011 that figure had risen to 92%. Russia, for its part, accounted for only 3% in 2007 and 2% in 2011. Also, this dependence on the Chinese market has seen constant growth in its absolute value, because the total amount of exports has tripled. In terms of imports, China was also Mongolia’s main provider in 2011 (30%), followed by Russia (24%).

Cyber-attacks intended to spy on the Mongol government in 2013 were attributed to China. A recent attack credited to China has been analyzed by Threat Connect’s Intelligence Research Team (TCIRT), which published its results in October 2013.27 China is accused of using a cyber-espionage operation to try to learn more about Mongolia’s relations with the European Union28, the United States and other states such as South Korea and Japan. The attack took place through the dissemination of a compromised Word document29 seeming to contain non-classified information about the Khaan Quest 2014 exercise (a joint operation between Mongolia and the United States), and to come from the United States Army Pacific (USARPAC) Unit. Opening the document triggers the installation and activation of a malware package. The perpetrators of the operation used a second document in the form of a false memo from the Mongolian Ministry of Defense, regarding an exercise with the Vietnamese army. The C2 servers used for the attack were located in Hong Kong. The TCIRT investigation tracked the hack back to a young Chinese doctoral candidate at the Dalian University of Technology, named Yun Yan. The malware used also seems to have been employed by the hacker group APT1 analyzed in the Mandiant report in 2012.

6.2.2. Nationalism on the Internet

In Mongolian society, we are witnessing the emergence of anti-Chinese neo-Nazi movements, such as the group Tsagaan Khas (“White Swastika”) founded by Ariunbold Altankhuum, or the groups Dayar Mongol or Blue Mongol. These movements are taking shape in a society with a poor economy, pointing fingers at those whom they believe to be responsible for their situations, first among which are foreigners – Chinese in particular. These ultra-nationalists describe themselves as patriots defending the rights of ordinary citizens against crime, inequality and corruption, drawing inspiration from Nazism (although they claim to reject the violence of Nazism), and referring to heroes from the country’s history (such as Chingunjav30 or indeed Genghis Khan – a legendary leader whose story was repressed during the Stalinist era, but who remains a hugely significant figure in Mongol culture31) to defend their national identity.32 The demands of these ultra-nationalists relate to defense of the Mongol race, to fight against mixity, against the intrusion of China into the country, which perceived as an imperialist threat. The defense of the nation by these groups extends to protection of the environment (fighting against pollution caused by foreign mining companies).33 The members of the group Tsagaan Khas, which is seeking legitimacy and acceptation, appear to be adopting less violent practices in recent times. Yet they still act as militias, checking the operating permits of foreign mining companies, and patrolling the streets ensuring that Mongol girls do not have sexual relations with foreigners – particularly Chinese – (to keep the race pure). As is true the world over, these demands may be promulgated on Internet networks (for example, on YouTube). However, the actions and demands of these groups are causing waves and gaining widespread publicity in the reports made by the international media – particularly on the Internet.34

6.3. Information-space security policy

Conscious of the problems that cyberspace presents in terms of national security, but also probably at the urging of Western countries, the government has decided to implement a cybersecurity policy. Also, in order to drive forward measures to improve security in the country, Mongolia is and has been hosting international events relating to cybersecurity. On 27 January 2013, at the Defense University of Mongolia35, a conference was held about the future of information technologies, with 26 participants. The 5th APT Cybersecurity Forum (CSF-5)36 of the Asia-Pacific Telecomm unity (APT) was held in Ulaanbaatar, 26-28 May 2014, under the aegis of the Information Technology, Post and Telecommunications Authority (ITPTA) (Mongolia). Thus, cybersecurity is now part of a national security program (strengthening of the security protocols on institutional networks, institutionalization of cybersecurity) but is also playing a part in Mongolia’s international relations (prolonged international dialog by the organization of demonstrations on cybersecurity, facilitating debates and exchanges).

The government has adopted:

– the E-Mongolia National Program, defined by the Information and Communications Technology Authority (ICTA) for the period 2005-2012.37 This is a roadmap set out by the government for the development of ICT in the country. The primary objective is to use NTICs as the basis for some of the development of the society and economy on the national information infrastructure, by offering an “[equal], inexpensive, easy to use information communication service to all”. NTICs are perceived as the solution to numerous problems: “Create open information environment that provides information on government, economy, education, science, art, literature, business sectors and society at large. Apply ICT advantages in order to eliminate corruption, bureaucracy and other impoverishments. Preserve Mongolian historical, traditional and societal wealth. Diminish poverty…”;

– the 312th Resolution of “Measures on providing state information security”, in 2011. The Government Communications Department of the General Intelligence Agency was renamed the Cybersecurity Department, and its functions are to ensure the protection of the State’s information and important information infrastructures, evaluate risks, managing the government’s networks, and ensuring the integrity and security of those networks;38

– in 2010 the government approved the “National Information Security Program” (2010-2015). This document is the contemporary of a broad range of cybersecurity policies and strategies published in numerous countries, on all continents.

Information security is one of the six elements of this integral national security strategy39: “National security shall be assured through the interrelationship among the “security of the existence of Mongolia”, “economic security”, “internal security”, “human security”, “environment security” and “information security”; “The approach to security and action-making shall be based on knowledge, information and analysis.”

Information security is discussed in section 3.6: “Information security: Assurance of national interests on information and guaranteeing information integrity, confidentiality and availability for the state, citizen and private organizations shall be a basis for ensuring information security”.

The text hinges around the following major arguments:

– the crucial importance of information security for national security;

– information and its security support national development (also note that, at least in the English-language version of the document, the terminology used refers to information and information security, rather than “cyberspace”, “cybersecurity” or even “information systems”;

– the need to: “3.6.1.2. Restrict outside entities’ attempts to influence the social psychology, social stability and individual consciousness and ethics of Mongolians. Develop a capacity to disrupt or counter any information that promotes or supports animosity, discrimination or hatred and develop a social mentality of non-acceptance of such efforts”. This focus on influence and social stability, and the fight against anything which could jeopardize peace in the heart of society, is highly reminiscent of the approach taken by its two neighbors, Russia and China, whose security strategies are designed to safeguard information security – Russia speaks not of cyberspace but of information space – and guard against outside influence which could disturb the peace and potentially give rise to interethnic, political (etc.) tensions in the country – this concern is shared by China and Russia;

– the Mongolian authorities are perfectly well aware of the possibilities of intrusion into the networks and the danger that could represent for the economy, security, and society;

– foreign enterprises in the domain of the Internet are subject to strict scrutiny. The State cannot and will not accept these media being used as a propaganda instrument by foreign powers: “3.6.1.4. Rights of foreign-investment mass media activities in Mongolia shall be restricted if they harm national security. Ownership and association with media shall be transparent and their activities realistic, balanced and responsible. Support publication and promotion of national values through mass media and contain at proper level information on foreign religion, culture or state policy”. Thus, this policy entails the controlling of the activities of foreign media and of the content published;

– as in other states, including Western ones, the authorities have planned actions to raise social awareness of security issues: “3.6.1.5. Develop a national policy on legal arrangement, standard, management, organization and training on information security to enhance social awareness and information security knowledge”. “3.6.4.3. Establish a national security data base and develop a mechanism to provide citizens with wide-ranging information on national security through the State Great Hural, local government organizations and media. Maximize efforts to set up governance open information sources, methodologies and procedures to efficiently use these sources in the electronic governance services”;

– information security concerns both the government and private enterprises. The approach needs to be all-encompassing and holistic, and the security organized (risk management, security audits, etc.);

– information security requires the existence of a pool of high-level professionals (but nothing is said about the way in such a resource is to be constructed. Will the engineers trained in Mongolia’s own schools and universities have a sufficient level of expertise to satisfy the requirements?40);

– Mongolia touches on the debate about technological sovereignty, though that expression is not actually used in the text: “3.6.1.9. Support and develop national manufacture of competitive information and communications systems, equipment and software, develop solutions to national information security and reduce technological dependency”;

– in order to constitute a recruiting ground of national experts in information security and of innovative engineers and entrepreneurs, the country needs to invest in high-level training, and in R&D. “3.6.1.10. Specifically support national fundamental and applied sciences research, study and training on information and communication technology as well as information security”;

– there is a focus on “cybercrime”, but the first point in this brief discussion still stands. Indeed, this cybercrime takes place in a space which is not “cyberspace”, but rather is “information space” – in other works the policy is essentially in line with the Russian concepts: “3.6.1.11. Develop national capacity-building on computational forensics analysis to combat cybercrime or investigate, detect and collect evidence of crimes. 3.6.1.12. Develop and expand international cooperation to ensure information security, prevent the danger of confrontation in information space and combat cybercrime”;

– a subsection is given over to Integrity of information (3.6.2). Thus, the document emphasizes quality of information and the risks of manipulation of information (rather than manipulation of data). Thus, there is a visibly more marked interest in information operations, and information warfare, than in the notion of cyberconflict as such: “3.6.2.1. Integrity of information shall be ensured through protection of information, information space and infrastructure from illegal intrusion, manipulation or theft”;

– the solutions favored by the authorities are similar to those adopted in most States: ensuring specific protection of State data, State information systems, ensuring the security in the information infrastructures, putting in place a digital signature public key infrastructure, reducing the vulnerabilities of the networks, systems, and sites, encrypting exchanges, etc.;

– public–private cooperation needs to be one of the driving forces of security;

– a set of specific measures (legislational, in particular) needs to define different categories of information, and different levels of classification;

– in this document, the main focus really is on the government’s information, and on the data held by the State: “3.6.3.2. Refine government information categorization and security classifications, improve legal environment for management and organization of classified information protection to a higher level”. The protection of personal data is also mentioned: “3.6.3.7. Prohibit intrusion on individual or family privacy, correspondence, information confidentiality, rights and freedoms except in cases of ensuring national security and following all legal procedures”.

In 2012, the Ministry of Defense published the Operational strategy of the Ministry of Defence41, which envisages the forces to be restructured and for them to employ new technologies. Cybersecurity is briefly touched upon in the paper, although no discussion is specifically dedicated to the issue. However, the army is facing the issue of cyberdefense, having itself fallen victim to cyber-attacks targeting it either directly or indirectly (see the cyber-attack as part of Khaan Quest 2014 mentioned above). Mongolia intends to profit from its cooperation with NATO to extend its cyberdefense activities.42 Yet in spite of these new-found friends, Mongolia is not entirely breaking off its military relations with China43, as the mutual trust agreement signed in 2003 between the two countries was transmuted into a strategic partnership in 2011. China is Mongolia’s economic and political partner, and remains so in spite of Mongolia’s efforts to find a third neighbor.44 The cyber-attacks in 2013 attributed to China are unlikely to jeopardize these relations.

1 [http://www.internetworldstats.com/asia/mn.htm].

2 [https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mg.html].

3 [https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mg.html].

4 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mg.html.

5 Kristian Feigelson, Mongolie : la démocratie nomade, Études 5/ 2003 (Volume 398), p. 597–607. URL: www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-2003-5-page-597.htm.

6 [http://www.budde.com.au/Research/Mongolia-Telecoms-Mobile-and-Internet.html].

7 The statistics can differ significantly. The figures published by the ITPTA (Space Program in Mongolia) in 2013 speak of 641,000 Internet subscribers for 2012, which represents a 40% increase on 2011 (457,000 recorded subscribers).

8 [http://www.internetworldstats.com/asia/mn.htm] (for 2000, 2001, 2007, 2009 and 2010).

9 Tian-Syung Lan, Chun-Hsiung Lan, Oyuntuya Tserendondog, “Analysis of social network sites diffusion in Mongolia”, African Journal of Business Management, Vol. 5(23), pp. 9889–9895, 7 October, 2011, [http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM].

10 White Paper on ICT Development, Mongolia – 2013, ITPTA, 2013.

11 [http://www.mad-mongolia.com/news/mongolia-news/%E2%80%9Cevery-day-mongolian-websites-are-hacked-by-the-dozen%E2%80%9D-7960/].

12 [http://ubpost.mongolnews.mn/?p=5561]. Mongolia’s penal law does not sanction hackers, which creates favorable conditions for them to act with total impunity. The law prohibits the dissemination of pornographic content and defamation. However, the legal framework as yet remains relatively cursory in terms of the Internet.

13 [http://www.mad-mongolia.com/news/mongolia-news/%E2%80%9Cevery-day-mongolian-websites-are-hacked-by-the-dozen%E2%80%9D-7960/].

14 http://www.zdnet.com/russian-space-systems-hacked-in-lurid-attack-3040094018/.

15 www.lupm.org/chinese/pages/120529c.htm.

16 Source: [http://www.lupm.org/chinese/Pictures/nmg/LUPM.jpg].

17 Kristian Feigelson, Mongolie : la démocratie nomade, Études 5/ 2003 (Volume 398), pp. 597–607. [www.cairn.info/revue-etudes-2003-5-page-597.htm].

18 Kalei Rupp, Department of Defense officials talk policy, cybersecurity with Guardsmen, 3 May 2012, Office of Public Affairs, State of Alaska, [http://dmva.alaska.gov/content/Press_Releases/2012/Department%20of%20Defense%20officials%20talk%20policy,%20cyber%20security%20with%20Guardsmen.pdf].

19 [http://eeas.europa.eu/mongolia/index_fr.htm].

20 Mongolia – European Community, Strategy Paper. 2007-2013, 23 February 2007, 42 pages, [http://eeas.europa.eu/mongolia/csp/07_13_en.pdf].

21 [http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2011/03/31/mongolia-information-and-communications-infrastructure-development-project].

22 Country Strategy Paper (2002-2006) – Tacis National Indicative Programme (2002-2006), Mongolia, 27 December 2001, 31 pages, [http://eeas.europa.eu/mongolia/csp/02_06_en.pdf].

23 Country Strategy Paper (2002-2006) – Tacis National Indicative Programme (2002-2006), Mongolia, 27 December 2001, 31 pages, [http://eeas.europa.eu/mongolia/csp/02_06_en.pdf].

24 [http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/mongolia/index_en.htm].

25 [http://www.nato.int/cps/fr/SID-66692911-82159886/natolive/news_85430.htm].

26 Calculated using statistical data published on the site [http://mongolianembassy.us/about-mongolia/trade-and-economy/#.U3SOTfl_vX4]

27 7 October 2013. [http://www.threatconnect.com/news/khaan-quest-chinese-cyber-espionage-targeting-mongolia/].

28 http://www.threatconnect.com/news/khaan-quest-chinese-cyber-espionage-targeting-mongolia/.

29 “DRAFT MSG – KQ14 – CDC ANNOUNCE MESSAGE.doc”.

30 One of the two great leaders of the 1755-1756 rebellion, fighting for independence from the Manchus (China).

31 Genghis Khan’s image is found on Mongolia’s banknotes, and statues have been erected in his effigy throughout the country. In the neighboring countries, this cult is perceived as a resurgence of Mongol nationalism.

32 Tania Branigan, Mongolian neo-Nazis: Anti-Chinese sentiment fuels rise of ultra-nationalism, The Guardian, 2 August 2010, [http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/aug/02/mongolia-far-right].

33 A Mongolian Neo-Nazi Environmentalist Walks Into a Lingerie Store in Ulan Bator, The Atlantic, 6 July 2013, [http://www.theatlantic.com/infocus/2013/07/a-mongolian-neo-nazi-environmentalist-walks-into-a-lingerie-store-in-ulan-bator/100547/].

34 For instance, see the reports published by western media: [http://www.theatlantic.com/infocus/2013/07/a-mongolian-neo-nazi-environmentalist-walks-into-a-lingerie-store-in-ulan-bator/100547/], [http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/aug/02/mongolia-far-right], etc.

35 [http://www.dum.gov.mn/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=440%3A-2013-&catid=49%3A2011-02-08-05-45-33&Itemid=159&lang=mn].

36 [http://www.aptsec.org/2014-CSF5].

37 E-Mongolia National Program, Information and Communications Technology Authority (ICTA), 3 pages, [http://workspace.unpan.org/sites/internet/Documents/UNPAN044899.pdf].

38 [http://www.infomongolia.com/ct/ci/3440].

39 National Security Concept of Mongolia, [http://mongolianembassy.sg/concept-of-national-security/#.U1e7tPl_vvY].

40 According to the White Paper on ICT Development, Mongolia – 2013 published by the ITPTA, in 2013, some 8023 people are employed in the NTIC sector: 7313 university students specializing in the following disciplines: software engineering, network administration, information systems and management, hardware engineering, telecommunications engineering, electronics engineering, optic communications, television and radio technology, satellite and wireless communications, and information technology.

41 [http://www.legalinfo.mn/annex/details/5610?lawid=8768].

42 NATO and Mongolia agree programme of cooperation, 19 March 2012, [http://www.nato.int/cps/en/natolive/news_85430.htm?selectedLocale=en].

43 Alicia J. Campi, Efforts to Strengthen Sino-Mongolian Relations in Fall 2013, China Brief Volume: 13 Issue: 24 December 2013.

44 Ganzorig Dovchinsuren, Mongolia’s Third Neighbor Policy: Impact on the Mongolian Armed Forces, United States Army War College, March 2012, 40 pages, [http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA561642].