Chapter 3

Close: To Bridge the Saying-Doing Gap, Act Like a STAR

They thought he had lost his mind. The business was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, but the CEO had latched onto a decidedly nonstrategic topic: workplace safety. No one could possibly say it was unimportant, but concerned investors wanted to hear details about markets, revenues, and profit. Where was the business plan?

An analyst asked about finance metrics. Nothing doing. “I'm not certain you heard me,” the CEO answered. “If you want to understand how Alcoa is doing, you need to look at our workplace safety figures.”

You might recognize the speaker as Paul O'Neill, who merits a whole chapter in Charles Duhigg's The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business.1 O'Neill used that power to engineer an amazing turnaround. A year after he gave his unexpected lecture about workplace safety to a group of dismayed shareholders and industry observers, company performance had rebounded and profits had reached record highs.

In bringing Alcoa back from the precipice, O'Neill pursued a strategy embraced by successful managers and team leaders to close the gap between aspirations and action: he got specific. He avoided the all-too-common CEO “cheerleading,” as he put it dismissively, and focused on just one concrete thing. Research on positive behavioral change has confirmed the efficacy of pinpointing measurable actions and monitoring small, step-by-step improvements. For example, would-be fitness fanatics rarely stick with their workout plan if they target an abstract goal like: “Get in shape.” They do much better when they set concrete milestones, such as: “Go to the gym three times by next Friday.” What works for individuals works for teams and organizations, as O'Neill demonstrated in dramatically improving Alcoa's operations.

Getting specific is the key to closing the saying-doing gaps that you identified using the tools we introduced in the previous chapter. Once you have observed misalignments and set the stage for having productive discussions about them, you can work with your team on getting committed again. Elite athletes close the gap by getting specific, and so do artists, scientists, and managers. Specificity is the key to acting like a STAR, a process we explain in this chapter.

Swimming in the Deep Water

Like Paul O'Neill, high-performing team members avoid cheerleading when they are giving each other feedback. They identify specific behaviors that help or hinder performance and suggest ways to implement or enhance them. For example, an EDP participant named Adedayo noted after some reflection that he expressed his ideas like a “machine gun” in team meetings, spraying his words indiscriminately around a conversation and killing his group's creativity. At the end of a decision-making session, his teammates told him to talk 75 percent less the next time. The definite target helped Adedayo calibrate his contributions and gave others an opportunity to bring their proposals out into the open. By getting specific, the team narrowed the saying-doing gap between a high-level commitment to out-of-the-box thinking and the way group discussions had actually been going.

In this sense, HPTs engage in “deep” versus “shallow” discussions about goals, norms, and behaviors.2 We borrow this distinction from University of California anthropologist Mica Pollock, who has shown that abstractions rarely capture the reality of how groups and organizations operate. In the early stages of commitment-setting, HPTs may start by discussing intangible goals like “winning,” “greatness,” and “creativity,” but their attention later turns to particulars like the amount of time spent on a topic or the number and kind of comments made by a team member. (Think Adedayo the machine-gunner.) As HPTs develop, they swim from the conversational “shallows” into the “deep waters” of specific feedback. HPTs navigate these waters by acting like STARs—a process that starts with getting specific and includes using behavioral prompts.

It takes work to move into the deep water. A poignant scene in the acclaimed film Boyhood illustrates the difficulty. Ethan Hawke's character Mason Sr. is driving his son and daughter home from school after having been away. As we have all done countless times in small-talk conversation with our loved ones, Mason Sr. asks the kids a mind-numbing, general question: “How was your week?”

The younger Mason and Samantha offer the typical adolescent responses like “fine” and “pretty good.” Suddenly seeing this moment as a sign of growing distance between himself and his children, Mason Sr. pulls over the car and demands they engage him with more seriousness.

“Dad,” Samantha retorts, “these questions are hard to answer… they are too abstract.”

The son interjects, “What about you, Dad? How was your week?”

Mason Sr. pauses for a moment and admits, “I see your point.”

When it comes time to discuss team problems, we tend to make statements like, “Let's talk about the issues,” and remind team members, “There are no wrong answers,” and urge them to “Check egos at the door.” Like the question “How was your week?” these pronouncements get at the right idea but fail to create the space for people to actually reflect and respond honestly. They are just too abstract.

Situational Awareness: Ambitious Goals Are Not Enough

On May 25, 1961, John F. Kennedy announced to a joint session of Congress3 that the United States “should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” His words rank as one of the most visionary appeals in recorded history and are often cited as a model for leaders of motivational rhetoric.

The months of careful preparation that preceded JFK's address typically receive far less attention, but we think they constitute the heart of the real story. For it is the preparation that ultimately made the stirring lunar-inspired words so powerful and memorable, even though they accounted for just a fifth of the famous speech that also addressed several other urgent policy challenges such as a badly flagging economy and national security. Facing plenty of sublunary problems that would have stressed even the most capable executive team, the president and his advisors were willing to go public with the audacious moonshot goal because they had already won support for it behind the scenes from influential politicians, scientists, economists, and government administrators.

Before his election as president, Kennedy displayed little interest in space exploration, and he delegated the responsibility for the lunar landing issue to Vice-President Lyndon Johnson, who was deftly positioning the space program with key senators such as Robert Kerr, chairman of the Space Committee. Kerr made no bones about serving parochial interests, including his own. He openly admitted, “I represent myself first, the state of Oklahoma second, and the people of the United States third, and don't you forget it!”

Johnson therefore made sure Kerr knew that he and his constituencies would benefit from massive investments in the technology required to send astronauts on a round trip to the moon. Kerr then played an important part in selecting the new head of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA): James E. Webb. Despite his initial doubts about the moon mission, Webb had the right mix of political skill, energy, and charisma to advocate for JFK's agenda with law-makers and military brass.

Bottom line: By the time the president made the historic address to Congress, he could bank on critical support from a host of well-placed people he needed to realize his goal. Walter A. McDougall, the level-headed historian4 who wrote the definitive account of the Apollo years, put the point as baldly as possible. All the major figures—Kennedy, Johnson, Webb, Kerr, and many others—“saw ways in which an accelerated space program could help them solve problems in their own shop or serve their own interests.” Because JFK was in touch with the practical reality of his situation and had aligned a whole team behind his vision, he felt comfortable making a strong case for the lunar program.

Since gaps easily develop between reality and ambitious goals, HPTs are always working to maintain situational awareness and fine-tune both their ambitions and actions accordingly. The way Kennedy and his team positioned the Apollo program is a historic success story in this regard. But another story, about the tragic events that overtook the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshot Crew, shows how hard it can be to balance goals against a complex and ever-changing situation.

The Hotshot crew was an elite team if ever there was one. In every part of the United States, the crew fought wildfires that had become raging, rolling infernos that threatened flora, fauna, and all things human. Eric March led the Granite Mountain hotshots, and he did everything right in creating the conditions for peak performance. He set goals—you can even call them transcendent goals—memorialized in a dramatic manifesto:5 “Why do we want to be away from home so much, work such long hours, risk our lives, and sleep on the ground 100 nights a year? Simply, it's the most fulfilling thing any of us have ever done. We are not nameless or faceless. We are not expendable. We are not satisfied with mediocrity, we are not willing to accept being average. We are not quitters.”

March handpicked his team, probing each recruit to determine if he had the necessary skills and character. Character was paramount, because the team had to be committed to truth-telling. “When was the last time you lied,” Marsh asked every interviewee. Once selected, teammates knew exactly how they fit into the crew. Finally, the team had clear norms that everybody had signed off on. The norms were based on meticulous analyses of fatal fires and included the safety system called LCES: Lookouts, Communications, Escape Routes, and Safety Zones. Training drilled the LCES protocol into the crew.

You might conclude that the Hotshot crew was the perfect team: goals, roles, and norms—the key HPT success factors—were all founded on a commitment to truth-telling. No one would use the word “perfect,” however, to describe the outcome of the Hotshot Crew's engagement with a fire that bore down on Yarnell, Arizona, in June of 2013. Just the opposite: A heartbreaking scenario unfolded that claimed the lives of 19 elite firefighters.

What happened?

Though the full answer is obviously complicated, the Industrial Commission of Arizona reached a striking conclusion: the Arizona Forestry Division had “implemented suppression strategies that prioritized protection of non-defensible structures and pastureland over firefighter safety.” The bureaucratic language obscures an insight articulated by one of the firefighters who survived the blaze. “They wanted to reengage,” said Darrell Willis of his comrades who lost their lives. “Sure, they could sit up there in the black [i.e., a safety zone, protected from the encroaching conflagration]. But if they could try to get back into the game, they were going to.” In other words, following the LCES protocol, the Hotshots had retreated to a safety zone, but then left it to continue battling the flames.

To put it bluntly: the Hotshots did precisely what they should not have done. As Willis reported, “We said we're never going to let this happen to us. It was kind of like a commitment: we can't let this happen to us.” But happen it did, because they made a decision that was obviously flawed, in terms of their own protocol and manifesto.

Long story short, situational factors overwhelmed the Hotshots. One of the most important factors was that they were exhausted. A hiker who encountered the firefighters on the way to their final stand took a photograph that captured a disturbing fact. Men trudged uphill in 90-plus degree temperatures, lugging heavy tools and backpacks, their visibly strained faces dripping with sweat. The walls of the Hotshot headquarters where the Hotshots started the day were covered with posters that emphasized the basics: “Don't Let Wildland Urban Interface change your Situational Awareness. Your life is more important than any structure!” If you are rested and calm, this exhortation is blindingly obvious. It is anything but obvious when you are stressed, tapped out, and facing a roaring inferno.

This helps explain why HPTs rely on checklists and prompts: simple reminders to perform the most basic actions in the right way, even as intense situational pressures are making it hard to pay attention to details. In the abstract, high-performing teamwork seems to be based on the science of the blindingly obvious (commit to shared inspirational goals, communicate clearly, support decisions reached by the group, etc., etc.). In reality, however, it is just very hard to remember what to do under the conditions in which most people do their work every day: surrounded by raging fire, on the battlefield, in a cockpit or operating room, even in a conference room facing down a deadline and worried about looking bad.

High-performing teamwork is based on the interactive process of cultivating an ability to notice and respond to the seemingly insignificant details that matter most to closing gaps between goals and action. The process underlies successful firefighting, surgery, office work, parenting—indeed, any activity that requires working with and through others to reach a specified outcome.

Act Like a Star

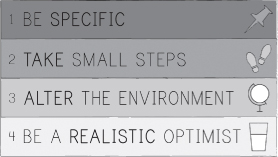

Our field research has shown that HPTs create the conditions for peak performance by acting like “STAR”s.

The four STAR steps are the key to closing the saying-doing gap. Each step has its own guidelines, which HPTs adapt to suit their unique circumstances. We explain this model below, and provide you with a condensed version in the Resources section.

1. Be Specific

In order to make improvements, teams need to be hyper-specific about the changes they want to make. This can be tough. Just ask the Apple engineers who endured the brutality of Steve Jobs's special kind of feedback. Andy Grignon, one of the architects of the original iPhone6 and a member of the team that brought it to market, remembers how Jobs would express his displeasure if your actions failed to measure up to his expectations.

“He just looked at you,” Grignon reports, “and very directly said in a very loud and stern voice, ‘You are f---ing up my company,’ or, ‘If we fail, it will be because of you.’ He was just very intense. And you would always feel an inch tall [when he was done chewing you out].” While we do not recommend you deliver feedback in the same way, it worked for Jobs because everyone had signed on to the goal of creating an “insanely great” product and was comfortable enough to look past the abuse and see exactly what needed to be done differently.

With all due respect to Steve Jobs, you need not cut your team members down to build them up. You can encourage them to change while you deepen feelings of openness and trust. But you do need to go from shallow to deep with your feedback if you expect team members to take action.

A powerful tool for helping your team drill down into specific changes is the Start/Stop/Continue exercise. It unfolds in simple steps:

- Divide a flipchart or white board into three vertical sections.

- Ask team members to write on individual Post-it notes the specific action they want to start doing, detrimental behaviors they think the team should stop, or positive practices the team should continue.

- Place each Post-it in its proper place on the board.

- Review the postings to see whether there are common themes and consider collectively what you want to change or encourage in the group dynamic.

Start/Stop/Continue is an easy and effective way to spur reflection and develop a behavior-change mindset. It helps you brainstorm ideas for change in an inclusive way that helps you visualize end goals. Try it in your next meeting as a way to get specific about your options for closing the saying-doing gap on your team.

To test whether you have gotten specific enough in this exercise, use visualization and measurement. If you would be unable to see a teammate acting on the feedback and count the number of times he or she does, then you should work on making your comments more concrete.

Amy Edmondson tells the story of 9 a top management team that was working to develop a new corporate strategy. The situation was urgent and called for specific, actionable steps toward change. But you would not have known it from the conversation. The team consistently spoke in abstract metaphors, such as the popular ship analogy that is all too familiar to anyone who has been involved in a change initiative:

Listening to Bob talk about the ship, I'd like to explore the difference between the metaphor of the ship and how the rudder gets turned and when, in contrast to a flotilla, where there's lots of little rudders and we're trying to orchestrate the flotilla. I think this contrast is important. At one level, we talk about this ship and all the complexities of trying to determine not only its direction but also how to operationalize the ship in total to get to a certain place, versus allowing a certain degree of freedom that the flotilla analogy evokes.

If you are feeling lost at sea, you are not alone. The team was still adrift six months later as they struggled to turn their abstract conversations about strategy into concrete action.

Applying the see and count test will tell you whether your feedback goes deep enough. For example, consider the difference between saying, “I want you to listen to me,” and, “The next time we have a conversation, I want you to wait three seconds before you respond to me and restate my point before you make another one.” The second statement defines what you mean by “listening,” while the first is way too abstract.

2. Resolve to Take Small Steps Toward Improving

Let's continue with the example of listening. If you agreed to wait and restate a teammate's words before making another point, you would have resolved to make a small step toward improving communication. Top performers improve by making small steps, and so do HPTs.

Consider the career of Steve Martin,12 a top performer in several fields: stand-up comedy, writing, and film directing. As he tells his story in Born Standing Up, he committed himself to doing “consistent work” on his material, making small adjustments to become ever better. Once, at a show delivered in a Vanderbilt University classroom, he finished his act, but no one in the audience of 100 students left. He started picking up his props and still the students remained sitting. Finally, he said, “It's over.”

No movement.

He realized the only way out of the room was through the audience, so he headed for the door, walking among the crowd and ad-libbing. The delighted audience followed him out the door and into the campus, where the merry revelers and its surprised leader came upon an empty swimming pool. “Everybody into the pool!” Martin yelled, and then he “swam” across a sea of upstretched arms. Reflecting later on the evening, Martin realized he had “entered new comic territory.”

Top performers improve in just this way, experimenting in small ways as they deliver results. Each small improvement makes them better. They focus on learning specific things and avoid self-defeating lofty greatness-type goals. As Martin puts it: “I learned a lesson: It was easy to be great. Every entertainer has a night when everything is clicking. These nights are accidental and statistical: like lucky cards in poker, you can count on them occurring over time. What was hard was to be good, consistently good, night after night, no matter what the abominable circumstances.” Top performers work on being good, and leave the judgments about greatness to others: the audience, the critics, customers, and bosses.

Great teams do the same thing. They work on making small improvements, one step at a time. Consider the story told by Mark McClusky about the team of British cyclers13 who dominated the global field of competitors. In Faster, Higher, Stronger: How Sports Science Is Creating a New Generation of Superathletes—and What We Can Learn from Them, McClusky relates how coach Dave Brailsford's team achieved greatness not through “luck or plucky can-do spirit.” They did it through the “aggregation of marginal gains.” McClusky explains: “Instead of looking for one earth-shattering change, British cycling takes a different approach. It looks at every aspect of performance, and tries to improve each a little bit—even just a tenth of a percent.” Steve Martin improved the same way, paying attention every night to the small changes he made—modifying just a tenth of a percent—and steadily enhanced his routine.

To work on small-step changes with your team, start by using “feedforward”. Why feedforward? Traditional feedback is important, but it tends to be heavily focused on what went wrong in the past rather than what can be done differently in the future. Leadership coach Marshall Goldsmith coined this term14 to highlight the importance of getting team members to look ahead toward specific ways to make positive change. To see how this works, consider a colleague who always shows up late to meetings. Rather than telling him, “You're always late and it prevents us from getting to important items on our agenda,” imagine saying something along the lines of: “If you aim to be at meetings ten minutes early, it will help us make sure we can get started on time and hit every item on our agenda.”

This feedforward empowers your colleagues by helping them think about proactive steps they can make to improve in the future rather than focusing on past failures. It shows the potential positive effects of a change. Rather than dwelling on what has gone wrong, it reduces defensiveness by focusing on what can be done differently. Practice feedforward with your team by creating a rule that any criticisms about past behavior need to be paired with one or two suggestions about what can be done in the future to create a positive change. You can set the tone by asking for feedforward about your own role on the team.

3. Alter the Environment

It is not easy being a jet-lagged American walking the streets of London. New World residents have a dangerous tendency to blunder into traffic coming from an unaccustomed direction—the right. Public authorities came up with a brilliantly simple solution to this problem. They painted two words on the street at the entrance to the crosswalk: “Look right!” Thankfully, this little reminder has saved many lives, including ours on business trips across the pond.

In addition to being a life-saving reminder, the pedestrian signs of London reveal an important fact about changing behavior: it often requires more than will power. When it comes to acting on a commitment, you might imagine you can “just do it.” But research shows that pure will-power is unlikely to be effective if the environment encourages old behaviors. Recall the story of PharmTec's change leader, Jenny, and the challenge she faced when she realized that everything about the company's environment contradicted the new values that were being shouted from the corporate mountaintop. How could she expect her reports to become more patient-centric when even the plaques on the wall encouraged them to help out pharm reps first?

You can alter your team's environment to make it more supportive of desired behaviors. Simple reminders often make the difference between success and failure. We think of reminders as “nudges.”15 We borrow the term from Nudge, Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler's study of “choice architecture.” Nudges promote decisions that support a set of goals or policies. The simple reminders on London street corners are an example. You can use similar ideas to encourage the take-up of new behaviors on your team.

One of the most effective nudges you can use is a checklist. Checklists help HPTs in cockpits, oil tankers, and hospitals perform the right tasks, in the right way, at the right time. Consider, for example, the massive problem of containing a virus like Ebola. What separates contagion and containment comes down to little details, like using three pairs of gloves instead of one, and applying hand sanitizer after stripping off each layer. It might seem easy to follow basic procedures for removing parts of a protective suit in a particular order. But remember that doctors treating Ebola patients are often physically and mentally exhausted by the end of a shift; under these circumstances, following the most rudimentary sequence of steps can be a challenge. When experienced professionals are tired and stressed, mistakes happen.

The most basic behaviors are easy to overlook, but they make all the difference in achieving success. As Atul Gawande observes,16 the operating room checklist for surgeons begins with a deceptively simple question: Am I operating on the correct patient? Perhaps an obvious question, but one that is easy to forget for that very reason. In the case of Ebola, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created a tailored checklist—a set of procedures that would instill new habits in care providers that are appropriate for managing the unique characteristics of this virus. The Ebola situation demonstrates how powerful checklists can be for reminding your team of the behaviors they need to follow.

Another powerful type of reminder is what we like to call an “accountability buddy.” This is our version of a gym buddy, who helps you meet your fitness goals. If you are trying to set better deadlines, or be more transparent about your opinions, ask a team member to observe your behavior and remind you when you are falling back into old patterns. Ask them to coach you on following through on your commitment. Accountability buddies are powerful because they leverage the power of positive social pressure.

Social pressure may be more valuable than money. Consider the conclusions reached by a team of Harvard and Yale17 social scientists who wanted to know why some groups achieve important collective goals and others fall short. The researchers studied different attempts to induce California residents to decrease water consumption during a recent drought. They found that the simple act of distributing mailers comparing water use among neighbors had the same effect as imposing a 10 percent price increase on water consumption. People who learned about the successful efforts others were making felt motivated to take action, too. The mailer leveraged social pressure to create positive change. Accountability buddies can help your team do the same.

In short, altering your team's environment by creating simple nudges makes behavioral change an easy choice, not an uphill battle.

4. Become Realistic Optimists

Leadership guru Jim Collins18 has shown that successful leaders are “productively paranoid.” HPTs have a similar collective mindset, which psychologist Albert Bandura calls “realistic optimism.”19

Everybody knows about the power of positive thinking. What many people believe about it, however, can be surprisingly wrong. Sure, it is pleasurable to think positive thoughts and imagine success—picture your team stepping to the stage at the annual corporate meeting to receive the award for excellence. But this fantasy can make you feel too good. When you feel good, you relax and run the risk of underperforming.

An HPT goes out of its way to anticipate problems. HPTs from top military units to cyber security groups use so-called Red Teams to reveal all of the risks inherent in a given strategic direction. Red Teams are either groups of insiders or knowledgeable outsiders who test a strategy by trying their best to defeat it. An elite hacker group might try to use whatever tools they can to infiltrate their company's IT security infrastructure, probing to find any weaknesses that may not have been thought of. Red Teams reduce groupthink and make sure your team's change strategy prepares for challenges that might arise.

Your own version of a Red Team could be someone in your group who is assigned the role of devil's advocate in your meetings, or it could be an external party you consult. The point is to make sure your thinking stays grounded in reality and accounts for the inevitable barriers that could lead to failure.

Go ahead and imagine how good it will feel to have worked out tomorrow. But follow up that exercise by dwelling on how miserable you will feel when the alarm goes off at 5 a.m. Then walk yourself through the steps you will take to actually get out of bed, put on your workout clothes, and head off to the gym before sunrise. For example: “If I wake up feeling exhausted and just want to pull the covers over my head, then I will turn to my right, switch on the lamp, and let the momentum of my movements carry my legs over the side of the bed and onto the floor.” Tomorrow morning at 5 a.m.—voilà—you are standing up ready to get dressed! No magic here—just the effects of implementing the fourth step of the STAR process.

Best-selling author Caroline Arnold20 has a term for small commitments like turning on the bedside lamp when the alarm sounds: microresolutions. A simple microresolution that HPTs nearly always make is to debrief a decision after it is made. Over time, the team develops the habit of reflection. The concept of reflection by itself is abstract. But note that the simple act of reflecting on outcomes turns an abstraction into an observable and measurable behavior. You can observe the action and count the number of times you perform it. Link reflecting with anticipating barriers, and you have a powerful combination.

You should also move from reflection to action in testing the feasibility of your planned changes. The concept of running small experiments originates in the popular Lean Startup approach to product development,21 but the principle behind the concept also applies to HPTs. Commit to finding small ways to test whether actions you want to take will work for your team and how they might be adjusted to overcome any problems you might encounter. Aiming for small adjustments and iterating rapidly, rather than taking on large-scale transformational changes all at once, is the key to successful behavior modifications and to maintaining momentum.

The Enormous Flywheel

Writing in the early twentieth century, the American psychologist William James22 called habit the “enormous flywheel of society.” It is easy to see why. Habits form the basis of the cultural rules that hold together teams, organizations, and societies. Cultivating habits by acting like a STAR is also the means through which individuals and groups enhance their performance in sports, art, science, business, and indeed any activity that drives toward a goal.

One of our clients acted like a STAR in turning around the behavior of a teammate who was underperforming in the most dramatic and disturbing way. Soon after Paul Smithey took over his state's multibillion-dollar Medicaid unit, he heard from several people about an employee—call him Mark—who was simply not working, doing literally nothing all day except pushing paper around. One day, Paul stopped by Mark's cubicle to have a conversation and noticed huge stacks of documents piled everywhere. Afterward, Mark's officemates approached Paul and cryptically urged him to “check the closet.” After hours, when Paul opened the closet door near Mark's cubicle, he made a horrifying discovery.

Mark had been moving documents from his desk and depositing them in the closet without even reading them. Paul was stunned. Responsible for following up on drunk driving citations, Mark had allowed hundreds of dangerous drivers to continue traveling the roads. Many bosses would have given Mark a high-minded lecture about the ethics of doing one's job and then fired him—with good reason. Instead, Paul invited the mother of a young man recently killed by a drunk driver to talk with Mark about the importance of his work and how much it meant to her. Her story brought him to tears, and he became one of the most engaged and productive members of Paul's team. The encounter with the grieving mother was the specific nudge—and the inspiration—Mark needed to start doing his work, do it passionately, and continue doing it every day. This nudge also set off positive ripple effects across the whole organization, sending a powerful message that dramatic change was possible.

Inspired by Aristotle, American philosopher Will Durant famously observed, “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”23 In the same way, HPTs are what they repeatedly do. They are thus always working hard to close the saying-doing gap. In setting commitments, they begin a process that leads to a meticulous focus on small, repeatable actions that produce a culture of success.

In closing this chapter, let's examine, from beginning to end, how one leader acted like a STAR in using the 3×3 Framework to turn around an underperforming team at major hospital.

Bringing It All Together: The Surgery Team Turnaround

One of our colleagues—call him Vince Taylor—showed what the 3×3 principles can do when he turned around a troubled team at an academic teaching hospital in the Northeastern U.S. After leaving his position at an Ivy League medical center, Taylor took charge of the research team in the hospital's esteemed specialty surgery department. He found what any outsider would call a toxic culture. The team was charged with administrating studies done by more than 10 surgeons in the department—recruiting subjects, obtaining the proper permissions, and tracking results. Cutting-edge research is the lifeblood of any academic medicine department, but this team had become a clogged artery.

Team members sometimes spent more time gossiping about each other than working on their assigned projects. The surgeons who relied on them complained bitterly about the low productivity of the team and the high turnover of leadership and staff. It didn't help matters that the department was juggling over 100 projects, some of them complex and high-risk. Taylor had been tasked with nothing less than reforming the division.

His first step was to establish new commitments. The team's counterproductive behaviors had been driven by a culture in which the most prominent unwritten rule was: “If you make a mistake, you will be an outcast.” In the first meeting with his new team, Taylor signaled a new direction when he introduced his key leadership principle: “If you struggle, we will give you the resources to succeed.” This became a kind of mantra. He made it clear that mistakes would be approached as a learning opportunity. Staff would be supported to maximize opportunities for success rather than castigated to minimize the chances of failure. He repeated his mantra in every meeting.

Taylor also knew that changing the culture would be more than a simple matter of issuing a grand proclamation. Transformation takes persistence and attention to detail, and the old culture was likely to continue living on in the everyday habits of his staff. Ever the careful observer, Taylor made note of team behaviors to check the alignment between the new values his team had committed to and what they actually did in the office. He knew it would take hard work to achieve that alignment.

Sure enough, he began hearing complaints about a young assistant, Katie, who was struggling to keep up with her duties. Before Taylor arrived, Katie was a terribly disorganized project manager. Her former supervisor had perversely lowered expectations as her performance flagged. For example, Katie was so frequently late to work that her official start time was changed from 8:30 a.m. to 9 a.m. The upshot: she started showing up at 9:10 a.m.

Co-workers began pushing for Katie to be fired. They called her a “lost cause” and an “underachiever.” But Taylor, who had been trained in anthropological methods, saw Katie's difficulties as a product of the old departmental culture rather than a sign of personal failings.

Instead of punishing Katie and perpetuating a destructive cycle, Taylor aimed to close the saying-doing gap. He supported Katie as he had committed to do. Looking back, it might seem obvious that he did the right thing. But remember the amount of pressure he was under at the time. He was a new director taking over a team supporting surgeons, most of whom expected quick results. When Taylor was confronted with a young, inexperienced employee who was clearly underperforming and whom most of the team wanted out, the obvious thing was not so obvious. It would have been much easier for him to appease the team by firing Katie and relieving himself of a substantial burden in the process. Putting his commitment into action in a stressful situation was by no means easy. What it required was a process and a focus on manageable change.

To be effective, Taylor focused on behaviors. He translated his mantra into concrete actions and helped Katie by focusing on behaviors she could change. The goal was to establish new, positive habits. Rather than setting low expectations and hoping Katie would meet them, Taylor set the bar higher and challenged Katie to surpass them.

Taylor began with a simple habit—showing up on time. He sat the young manager down and said, “From now on, you're going to get here at 8 a.m.” Katie was perplexed. If she had had trouble getting to the office at 8:30 a.m., how would it help to set the start time even earlier? Taylor told her that they would arrive together, giving her the nudge and support she needed to change her bad habit. Katie began setting her alarm earlier and was never late again.

Much to the team's surprise, Taylor began giving Katie more responsibility, not less. The team nearly had a panic attack when Taylor put Katie in charge of supporting an external audit on their compliance practices. Even the doctors Taylor's team supported were worried because of the visibility of the audit—any errors could delay important research.

It was a risky move, but it paid off. Katie discovered a talent for interpersonal relationships that she leveraged to keep the auditors happy and calm the anxieties of the surgeons about the process. Her performance improved so quickly, she ended up being promoted twice in short succession. The key to Katie's success was the way Taylor was able to change how she thought about her work. She had seen herself as a useless paper pusher, and the team culture reinforced that perception. Taylor showed her how her administrative responsibilities were the rock supporting the team, and he used specific tools and nudges to change Katie's behavior accordingly.

The hard work Taylor put into this reflective process with Katie and other members of the team paid dividends. Morale shot through the roof during his tenure, and the surgeons who complained previously about the group's work praised the surge in productivity they saw. He helped bring in many new research projects and transformed a money-losing division into a surplus-generating operation. The word spread around the university about the good work environment. People would stop in to ask if there were job openings and several people were hired.

Taylor's experience shows that creating and maintaining an HPT does not necessarily require heroic efforts or a soaring vision. It involves a continuous process of observation, reflection and adjustment focused on the small behaviors that lead to big differences in performance. Team leaders need not move mountains. It is more effective to close small gaps that make the difference between a team-in-name and a true HPT.