Chapter 8

Keeping Your Proposal on Track

IN THIS CHAPTER

Devising a workable proposal development schedule

Developing and managing proposal budgets

Building an effective proposal team

Many people believe proposal management is a lot like project management, and they’re right to an extent. Like projects, proposals have deadlines and milestones. Like major implementation projects, proposals often require you to manage the activities and contributions of a large team of specialists. And, like all major internal or external business projects, proposals can be just as complex, lengthy, resource-sapping, and bottom-line affecting, and can benefit from all the tools that help project managers deliver those projects successfully.

Yet proposal management adds another dimension to the management of a project: Document development and publication. That dimension is a different animal indeed. Proposal projects require scheduling the time of contributors and deadlines for their contributions, making sure all contributors are working off the most current and correct version of the document, establishing the structure of the proposal and associated content (based on either the customer’s preferences or yours), developing the order of that content (from declaring your intention to bid to final presentations to close the business), preparing the media used to display that content (from email to paper to a variety of digital formats), and, to top it all off, packaging and shipping the proposal, if required. It takes a master conductor to keep the whole thing on track.

In this chapter, we share how you can bring the proposal project in on time, within budget, and to the delight of a satisfied customer. Because your project’s success depends so much on the contributions of others, we also discuss how to build a winning proposal team, with the right people in the right roles with the appropriate skill sets.

Coming Up with a Schedule That Works

Planning, staffing, scheduling, funding, and managing a proposal project, reactive or proactive, is hard, time-consuming yet satisfying work. All this work is crucial to the success of any proposal, great or small. Without the right people doing the right things with the right resources at the right time, all in concert, a proposal will likely fail. And if the proposal fails, the sale will likely fail as well.

Old proposal writers (like us) have a saying: “No proposal ever won a deal all by itself, but plenty have lost them.” Proposals lose business all on their own by being ill-conceived, incomplete, or incompetently executed. Managing the time and resources you have can make all the difference. To do this, you must have a schedule — one that does the following

- Identifies the tasks to be performed for a particular opportunity

- Assigns a deadline for every task

- Encompasses each task’s essential action steps, their sequence, and their expected duration

- Balances the workload by maximizing the number of tasks that can be completed in parallel, while minimizing the number that must be done sequentially

- Ensures quality, compliance, responsiveness, and on-time delivery

You can devise a workable schedule for a proposal of any type, size, or degree of complexity by applying the principles that we discuss in the following five sections:

- Scheduling from the end to the beginning

- Breaking large assignments into smaller work units

- Working in parallel on tasks that don’t depend on other tasks

- Reviewing what works and doesn’t as you go along

- Managing the project day by day, even when milestones aren’t imminent

Beginning at the end and working backward

The key to a successful proposal schedule is to be aware of the time frame your customer sets and to begin scheduling milestones and activities at the point when the response is due and work backward to where you stand today (we outline these steps in the proposal process in Chapter 6). And even though that description may sound a little weird, the following sections describe how you can successfully set up the schedule from the beginning — oh, hang on — from the end to the beginning.

Setting (or adhering to) an ironclad due date

Many proactive proposals have loose due dates. Your salesperson may convince the customer that a problem needs solving, and so the customer says, “Bring me a proposal” with varying degrees of urgency. Your job is to firm up that date with the salesperson or the customer so you have an endpoint to aim for. Set this date in stone, even if your customer later extends the due date or if your salesperson gets distracted by other opportunities. In both reactive and proactive situations, extensions or delays are a pain to proposal managers because everyone else tends to relax when given more time and milestones are more easily missed. Avoid falling into this trap and the scramble that inevitably results when the due date suddenly looms.

Allotting ample time for production and delivery

Proposal production entails formatting, printing, assembling (sometimes of multiple volumes), and double-checking to ensure that everything is in the package or on the disk and that it complies with all requirements. Not all aspects of the production process are within your control, so you must be conservative when you schedule this activity, and protect this portion of the schedule above all others. Because production (even purely digital production) occurs late in the schedule, any activities that run late affect the production process.

If you’re going to adhere to the production schedule without sacrificing quality, you need to establish a firm cut-off time after which no changes can be made to the graphics or text. You must weigh the benefit of additional changes with the risk of faulty production or late delivery and resist editorial changes beyond a pre-established date and time. Maintaining a production checklist like the one in Chapter 16 can help you make the right decisions at crunch time.

Before scheduling tasks that occur earlier, be a little selfish. You need time to ensure a quality product that makes it to the customer on or before its deadline. Consider a range of contingency plans at the production and delivery steps; you never know what kinds of delays can occur if you outsource printing or if you must send the proposal package any significant distance. When you allocate time for production, consider the impact of worst-case contingencies, such as computer viruses, power outages, and equipment malfunctions.

-

Format documents parallel to the writing and editing process (as long as they’re separated by section or volume and organized in a logical manner that doesn’t impede progress or version/configuration control). For example, after you’ve written Section 1, send it to the production team for formatting while you begin on Section 2. After Section 1 has been formatted, the production staff can return it to you for final editing and formatting checks.

This parallel approach is ideal for large submissions; you or your production team can format smaller proposals after all writing and editing is complete.

-

Align document formatting with major review cycles. Remember that reviewed files may require reformatting, particularly if writers, editors, or reviewers introduce errors into electronic files. Generally, the larger the document, the more times it needs to be reviewed and potentially formatted or reformatted.

Most production specialists can format roughly eight pages per hour, using a document template. If you need to format your files more than once, include those iterations in your estimates to create an accurate understanding of how many hours you need in the schedule for completion of this work. Tracking this and other productivity metrics over time can bring huge benefits to your scheduling process.

Allocating time to establish the proposal infrastructure and plan the rest of the project

This is one out-of-sequence task that you should work into your schedule early. Setting up a proposal infrastructure (that is, an online or physical workspace for authoring and sharing documents, controlling content versions, communicating with team members, collecting data and artifacts, and managing workflow) and creating realistic plans are critical for a successful proposal because both decrease your overall effort. When responding to an RFP, your planning process can take from 10 to 20 percent of the total time available (this includes preparing for the kickoff meeting, setting up a collaborative workspace or tool, establishing a contact list, defining roles and responsibilities, and developing the detailed schedule).

Allowing sufficient time for proposal reviews

Anyone who works directly on a proposal is too close to the work to be able to review it for quality, compliance, consistency, and influence. To accomplish this crucial task, you need to bring in experts who haven’t been involved in developing the solution or writing about it to take a fresh look at the proposal before you publish it.

Beware: Reviews consume considerable time in your schedule. After each review, you must allocate additional time to read and understand the feedback and work it into the next draft. You also need time to determine how best to respond to reviewer comments. Depending on the size and complexity of the proposal, and the number and availability of reviewers, review cycles can take anywhere from half a day to a week. Determine the appropriate number of reviews early, and avoid adding review cycles unless the solution changes significantly or the due date is extended.

- Use a style sheet to ensure consistent content. Most large organizations have a corporate style reference for business writing. If yours doesn’t, use style guides such as the Associated Press Stylebook or The Chicago Manual of Style. For your projects, create a standard style sheet that denotes your preferred usage, punctuation, capitalization, and use of industry jargon and acronyms.

- Schedule downtime between writing and reviewing. A waiting period away from the document allows you to find errors and validate ideas more easily and without emotional baggage.

- Have your workplace peers edit your work to ensure high-quality content, style, and grammar. If you’re part of a proposal department, ask your peers to review your work and offer to do the same for them. Look for opportunities for substantive, grammatical, and general stylistic improvement.

- Create functional or technical reviews with your organization’s subject experts to ensure accuracy, persuasiveness, and appropriateness. Try to use objective reviewers not linked directly to the proposal in progress.

Considering your remaining time

After you set your infrastructure, planning, production, and delivery times, list the rest of the tasks that you need to start and complete between planning and production. Check out Chapter 6 for the detailed process steps in the proposal writing element of the proposal development stage to guide you as you list your tasks. At a high level, these steps include the following:

- Preparing the summaries

- Describing your solution and matching it to the customer’s needs

- Writing the letter of transmittal

- Writing, editing, reviewing, revising, and proofing the content

We know what you’re thinking … hey, that’s the bulk of the work! And you’re right — it is from a labor standpoint. But the ultimate success of the detailed “creative” work really depends on the standard proposal elements we cover in Chapter 9, which provide the foundation for a quality proposal.

Sequencing the tasks and subtasks

As you develop your schedule, include as many levels of tasks as you need to describe the work in detail. Be sure to identify any dependencies for each task (such as supplies, approvals, or other tasks that need to be completed before another can begin or be completed). A detailed task schedule ensures that each activity reflects the best use of time and resources.

Here are some tips for establishing and ensuring accountability:

- Set the start and end dates for each major task and subtask. Set these dates by team member and for the project as a whole.

- Post each assignment on the proposal schedule, the project timeline, or in the collaborative workspace. Note names, task descriptions, task durations, outcomes, and deliverables.

- Explain the assignments to all team members. Make sure they understand their start and end dates and get them to commit to meeting their deadlines. Explain the consequences for your bid if they miss these deadlines.

-

Ensure that one person alone is accountable for a task or subtask. That person can, and often must, reach out to others for help, but he must take accountability and ownership for the task. If the owner has to transfer the task to someone else, make the handoff to the new owner clear and explicit.

Be transparent, reasonable, and honest about the schedule with all team members. Respecting team members’ time will help you gain their trust.

Be transparent, reasonable, and honest about the schedule with all team members. Respecting team members’ time will help you gain their trust. -

Remind team members of their commitments. Advise them that you’ll publicly announce the upcoming start and end dates in team review meetings. Let them know that you’ll also remind them privately. Many collaborative platforms allow you to send calendar reminders when task deadlines are approaching. If you don’t have such a platform, send “friendly” reminders via email a day or two before the deadline and copy in the boss.

These tactics may irritate some people, but everyone will thank you when the proposal is finished.

- Stay focused on the end result. If you discover that your team members are working on tasks that you haven’t placed on the schedule, either assess their value and revisit the schedule to add them or clarify the work assignments for the team. If your team is working on multiple ongoing tasks or tasks that have long lead times (the time between knowing a task must be accomplished and when it’s due), set a series of near-term, interim deadlines to drive priorities and keep them on track.

Publishing your schedule in a variety of formats

Your team members can’t adhere to a schedule if they don’t know it exists. You must ensure that the proposal schedule is visible and clear to the entire team, preferably on a collaborative platform that enables easy access and updates when needed. If you don’t have access to a collaborative platform (see Chapter 13 for more on proposal tools), create a timeline in project management software, on a spreadsheet, or in a calendar view.

Not everyone sees a schedule in the same way. Some contributors need to see only certain elements and deadlines for which they’re responsible. Some may be constrained by software (they may not have your project management application). Be ready to provide the schedule in an appropriate format for the project’s complexity and the individual contributor’s needs. If you work in an online system, the format may be set. But you don’t always need a Gantt chart or even a spreadsheet to keep people on track (they’re great for complex bids with lots of contributors and milestones). For less complex bids, consider using the Word-based, sample schedules for 10-, 30-, and 60-day proposals we provide online via the appendix. You can adapt them easily for your specific needs.

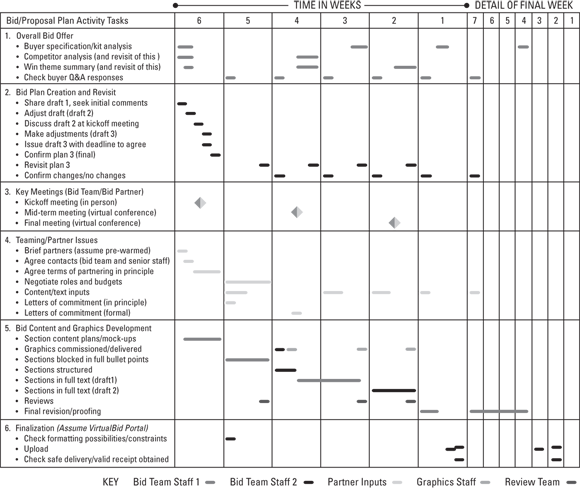

Gantt charts are the most common format for this kind of plan. A Gantt chart is a grid that maps and allocates tasks on the vertical axis against time scales on the horizontal axis. Gantt charts are widely used in both proposal planning and wider project management. (They’re also known as horizontal bar charts.)

A well-conceived Gantt chart often underpins and expresses a bid process better than any other document. It typically shows the following elements:

- Stages of a bid process

- Start and end dates of specific tasks

- Milestones, key decision, and review dates (these are sometimes the same thing)

- Role allocation (by color-coding, shading, and so on) for bid team members and partners

- Prioritization of tasks (by color-coding, shading, and so on)

- Leave/vacation arrangements (you can then use a Gantt chart to help define or work around these arrangements)

Action-based plans typically have several iterations. When starting a new plan, initially start the process away from the grid. Capture all tasks and milestones on blank sheets of paper or on sticky notes. You can then order them on a grid.

Completed action-based plans for large-scale bids can be as expansive as multiple sheets of paper that you can post on a wall. However, a user-friendly, single legal or A4-sized page remains the most useful size for sharing, analysis, and discussion. If you want to record extra detail related to a particular stage, such as preliminary activities for a large, multistakeholder kickoff meeting or the many needs of the final pre-deadline phase, produce an “exploded” version of the plan for that time period.

Figure 8-1 shows an action-based plan in a Gantt chart format with task division and allocation. It also shows an “exploded” final week for mapping more intensive activity detail.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 8-1: This sample action-based plan in Gantt chart format illustrates how tasks can be allocated and executed over the course of a project.

Breaking big assignments into manageable chunks

Many members of your proposal team, particularly writers assigned to respond to whole proposal sections, can be overwhelmed by the size and scope of the tasks they face. (If you’re the lone proposal writer, we’re also talking about you.)

Think for a moment about what you’re asking them to do, all in an abbreviated time frame. They need to

- Research the content for their topic, either by talking with a subject matter expert or coming up with it on their own

- Adapt the content to meet your outline and the customer’s particular needs

- Embed win themes, customer hot buttons, proof points, and value propositions within their content to support the solution

- Find or create suitable illustrations for their content

- Write their content to the specifications you’ve set in your style sheet

- Submit to cycles of edits and reviews

All these tasks become intensified if a contributor lacks proposal writing experience or if deadlines are tight.

Maximizing parallel tasks and minimizing sequential tasks

Think carefully through all your schedule’s dependencies when you determine start and end dates for proposal tasks and subtasks. You need to schedule tasks that depend on each other sequentially, and if you have a large number of them, you may run out of available time. To the extent possible, create a task list that includes activities that you can conduct simultaneously, such as writing proposal text and making plans for proposal reviews.

Make sure you don’t assign the same people to tasks that have to be completed in parallel, unless you’re certain that they can actually execute them simultaneously. For tasks that have dependencies, check progress every day on the tasks they depend on. For complex proposals, use critical path scheduling to highlight sequential and parallel activities and allocate and track proposal team resources.

Learning from your experiences

Whether a bid is successful or not, capturing lessons learned is essential to improve your scheduling process and the schedules themselves. You need to build a mindset in your proposal team that allows you to repeatedly assess the effectiveness of your methods. By doing this, you can determine the “right amount of time” for tasks so you not only know how to plan the next similar engagement, but you can also see, over time, the average and optimal time required for these tasks.

Stopping to capture knowledge during your proposal schedule isn’t easy. It’s even more difficult when you’re working with large teams and using intricate processes. But when you supply your proposal teams with a standard to follow, you can more easily assess their performance and how this performance may be improved for next time.

To maximize the benefits of the lessons-learned function, it’s helpful to

- Implement a standard lessons-learned process and lead the development of common outputs and artefacts, like follow-up reports and action lists

- Add a lessons-learned review during each stage in the proposal process

- Document recent lessons learned in each new proposal plan

- Cover any changes these lessons learned bring to your standard proposal process in the kickoff meeting

Managing the moving parts

Managing your team’s day-by-day tasks is the engine that drives all successful proposals. For even the simplest of proposals, ask your team members to check in daily — preferably at the same time once or even twice a day — so you can check the proposal’s status, identify issues and risks, assign and follow up on tasks, and update everyone on any changes that may affect the schedule or elements of the proposal.

When you’re working on a complex proposal, you can rarely compress your proposal activities or skip your daily management tasks for any period and expect to succeed. But maintaining a consistent level of discipline isn’t easy.

One reason that daily management is so critical (and so difficult) is that proposal team members have limited budgets and time. They need to know how to prioritize activities in the near term. Most participants in the process don’t see the full arc of activity, and some may not even understand the strategy and the larger picture, despite your efforts to educate them. Day-to-day management helps everyone to focus on what’s important and keeps the entire team moving toward the ultimate objective: Delivering a winning proposal.

Budgeting Your Funds and Resources

Proposals are expensive for two reasons. First, they take time from a lot of expensive specialists, people who are paid well to do jobs that in most cases only tangentially include proposal writing. When they work on a proposal team, something has to give, and the loss in their normal productivity can be significant. Second, proposals require resources: physical resources to track the process (such as online proposal management systems and content repositories like SharePoint), human resources to work on the proposal, technical resources to develop the solution and content of the proposal, travel and lodging to transport and house the people working on the proposal, production resources to publish the proposal in digital or (more expensive still) paper formats, and delivery resources to send the proposal over sometimes long distances.

If you’re the sole proposal writer or a member or leader of a small proposal team, figuring out the budget for the proposal process falls to you. So you need to be able to budget not only the often paltry sums dedicated to creating proposals but also the time you have to spend on them, because you’re likely to be juggling the responsibility of several proposals all at once.

Budgeting your funds

Most large businesses budget for bid and proposal expenses. These budgets define the amount an organization is prepared to allocate for all proposals in a year, and they may allocate funds based on specific opportunities. A proposal budget may include the entire cost of winning the sale or only the cost of developing the proposal.

The following sections explore the proposal budget in more detail, including how to manage budget limitations.

Understanding the proposal budget

The biggest part of any proposal budget is labor, and this aspect of the budget may include permanent titles that are exclusive to creating proposals (for example, proposal manager, proposal writer, proposal editor, graphic designer, and production specialist), people who work in business development roles, and sometimes people assigned to reviewing proposals.

If you’re part of an in-house proposal team, you need to understand how bid and proposal funds are assigned and tracked. The more you know about the funds available, the more you can ensure that you have the funds to get the resources you need most for any particular opportunity. Just be aware that the amount budgeted for an opportunity is usually based on the bid’s importance to the organization’s growth strategy or its desire to retain an incumbent contract. The more efficiently an organization budgets for its resources, the more money it has to support a bid, maximize the number of jobs it can bid on, or “wedge” in an unexpected opportunity. For this reason, you need to advocate allocating funds to projects based on likelihood of return (read: winning a deal).

Building a proposal budget

Table 8-1 provides a list of potential budget-tracking areas.

TABLE 8-1 Proposal Budget Categories

|

Salaries (Loaded) |

Tools |

Direct Costs |

|

Business developers |

Collaboration environments (physical and virtual) |

Travel |

|

Contracts manager |

Software licenses |

Transportation |

|

Pricing analyst |

Printers/copiers |

Accommodation |

|

Opportunity manager |

Meals | |

|

Proposal manager |

Supplies | |

|

Subject matter experts |

Paper | |

|

Writers |

Ink, tabs, binders | |

|

Reviewers |

Digital media | |

|

Graphic artists |

Facility chargeback | |

|

Production specialists |

| |

|

Executive overhead |

In the appendix, we provide a link to a sample budget template you can use to record your potential proposal expenses. Any proposal budget is risky, because most proposal expenses are variable. For example, a customer may release an amendment to adjust requirements, which increases your labor costs as you respond to the new requirements.

If you build a budget, you need to track your expenses by it. Track and analyze all your expenses to increase your budget’s accuracy over time. Maintain performance metrics, and keep records of budgeted versus actual expenses.

Proving your value

Increasingly, proposal professionals are challenged to do more with less, while increasing productivity and maintaining win rates. Proposal budgets are shrinking while tracking reports and cost justifications are on the rise. Tracking your costs against detailed budgets, and then comparing those costs to the revenue your proposals help generate, can help you demonstrate your value to your organization. At the very least, it demonstrates that you’re a good manager of the resources that are allocated your way.

Small businesses usually have limited proposal budgets and limited access to collaborative software or equipment. You may be even more challenged if you’re the sole proposal support person because you have to be proficient in numerous competencies (for instance, sales support, proposal writing, and customer service) and with a range of software tools — yet you may not have clearly defined roles or responsibilities and even less authority.

- Setting standards for proposal content through templates and content reuse

- Relying on proven proposal development techniques that have worked for decades without extensive software and hardware

- Defining expectations and timelines for other personnel who work to support proposal development

- Being aware of outsourcing opportunities to provide development or production support in case of emergencies

Budgeting your time

If you’re the sole proposal writer or manager in your organization or department, you’ll usually be in great demand. When salespeople learn of your abilities and role, they’ll come running for your help, especially when they see the quality of the proposals you produce compared to what they can do on their own. And besides, their job is to be with customers, working through issues and presenting information that leads to sales. And, usually, they’re much better talkers than writers.

Before long, your time will be your most precious commodity. You’ll be tempted to say yes to every opportunity, but you can’t. If you do, you’ll burn out in months. No lie. Proposal writing is that intense.

It’s even intense when you’re part of a proposal team, with the right resources like editors, graphic designers, and production specialists. Too much work in succession is a prescription for PSS (proposal stress syndrome). Okay, we made that up. But we’re not making up the stress levels involved with the proposal writing process.

Here are three ways you can combat proposal-related stress:

- Track your time and overtime (paid or not) and report it. If you’re working 16-hour days consistently, after a while it will start to show in your physical appearance. Don’t let it go that far; provide your boss with a weekly report. You’ll either get a new colleague or a partner in finding a way to limit the workload. If you don’t get either, look for a new job.

- Qualify your proposals better. Keep records of what you win and lose. Debrief sales (or better still, customers) to help you understand why. When you see a pattern emerge, discuss it with the boss or your clients. Show how your efforts can be better spent on deals you’re more likely to win.

-

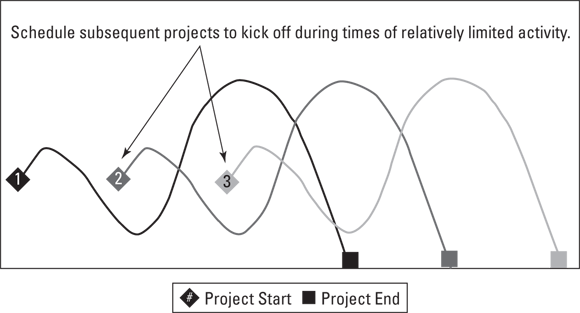

Create a staggered approach to scheduling your jobs. Proposals, especially less complex proposals, are funny in how they progress in cycles. At the beginning of a project, the work is intense. Then, when your subject experts are gathering material and crafting their solution, the work lessens. It then picks up with a vengeance toward the final days of the project, when the content comes in, reviews are set, and production begins. One person managing three projects can look like Figure 8-2.

Use the pattern in Figure 8-2 to launch a new project during the lull of the preceding one. Our proposal team did this for all our proposal managers, and they were able to successfully manage more proposals than anyone thought possible. Of course, you need to ensure that your team members get a break after a series of projects, or the burnout will return.

Use the pattern in Figure 8-2 to launch a new project during the lull of the preceding one. Our proposal team did this for all our proposal managers, and they were able to successfully manage more proposals than anyone thought possible. Of course, you need to ensure that your team members get a break after a series of projects, or the burnout will return.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 8-2: Staggering projects for a proposal writer to take advantage of normal peaks and lulls.

Choosing Your Proposal Team

Even if you’re the sole proposal writer for your organization, you can’t create a winning proposal on your own. Few people, maybe only sole proprietors or the most grizzled proposal veterans, have the requisite knowledge of the business, the customer, the solution, and the proposal development process to deliver a winning proposal without help. You need teammates to provide the knowledge, skill, and person-power to write a compelling proactive proposal or a Request for Proposal (RFP) response of any size. And choosing those teammates wisely can be as important to writing a winning proposal as any process, schedule, or resource. Proposing is a team sport!

To successfully staff your proposal team, you need to know the skills required and who has those skills. Today, the people you need may be spread all over your organization, or even the world. Sometimes your organization may need help from external partners. In this section, we investigate each of these situations in detail.

Understanding roles and competencies

The Association of Proposal Management Professionals (APMP) identifies all the key roles needed to manage the business development function in an organization. Although your business may not require all these specialties, understanding the different roles may help you choose the right people as you become a “proposing” organization.

Table 8-2 shows the common roles within a typical proposal organization.

TABLE 8-2 Common Proposal Roles

|

Role |

Description |

|

Knowledge manager |

A knowledge manager is responsible for the creation and ongoing maintenance of reusable knowledge databases. Knowledge managers use organization, writing, and information design skills to increase the business strategy value of an organization’s intellectual property. |

|

Production manager |

A production manager is responsible for planning and directing the printing, assembly, and final check of proposal documents. This role should have specialized skills in both traditional print and electronic media. |

|

Proposal coordinator |

A proposal coordinator is responsible for all administrative aspects of proposal development — ensuring security and integrity of all proposal documentation, coordinating internal flow and review of all proposal inputs, coordinating schedules, and directing submission of the final master proposal to production. |

|

Desktop publisher |

A proposal’s desktop publisher is responsible for designing, formatting, and producing proposal templates, documents, and related materials. |

|

Proposal director |

A proposal director is responsible for all aspects of an organization’s proposal operations. The proposal director ensures that a formal process exists and is in use. In addition, the proposal director is responsible for ongoing process improvement and may also manage the infrastructure (physical or virtual) within which proposal development functions are conducted. Proposal directors are often involved in broader business development activities, such as strategy development, staff development, and long-term business capability planning. |

|

Proposal editor |

Proposal editors are responsible for ensuring that the writing structure and words used in the proposal persuasively convey the offer to the customer. They edit for grammar, punctuation, capitalization, clarity, readability, consistency, and persuasiveness. |

|

Graphic designer |

A proposal’s graphic designer is responsible for developing customer-focused visual information that highlights an offer’s features, benefits, and discriminators. The graphic designer communicates with other members of the proposal/bid team to conceptualize and create visual elements to persuade the customer. Graphic designers may develop multiple deliverables such as proposals, presentations, sales collateral, and brand identities. |

|

Proposal manager |

A proposal manager is responsible for proposal development (such as writing, presenting, and demonstrating the solution), including maintaining schedules, organizing resources, coordinating inputs and reviews, ensuring bid strategy implementation, ensuring compliance, resolving internal team issues, and providing process leadership. |

|

Proposal writer |

Proposal writers are responsible for creating and maintaining content for common proposal sections, such as past performance, résumés, and reusable product and services descriptions. Subject matter experts that contribute content are also referred to as proposal writers. |

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

Managing virtual proposal teams

In recent years, businesses have come to invest in virtual proposal teams to acquire business. Collaborative working environments are almost ubiquitous, allowing remote access to tools and information as if all resources were co-located.

Proposal teams can plan, manage, and deliver on all phases of proposal development from almost anywhere in the world. To remain competitive and address the work-life balance that employees demand, businesses need to focus on ensuring that collaboration tools provide the needed features and functions their teams need, regardless of where they work, always bearing in mind any security considerations. For more about these tools, see Chapter 13.

Supporting global teams

Global teams must clarify specific terminology that may differ regionally (such as the term binders versus folders), design concerns (such as color usage in specific countries), and physical production concerns (from paper sizes to production times). These concerns can be mitigated through clear communication early in the process.

Working with external partners

The larger and more complex an opportunity is, the greater the need for bidders (especially small businesses) to join with other organizations to satisfy the requirements of an RFP. This is where things can get very complicated, because assembling a winning team requires a delicate balance of strategy and tactics. While an effective partnering strategy can significantly improve a bidder’s win probability, a poorly executed strategy can create serious performance, reputation, legal, and financial problems.

The following sections help you decide on partners should you find them necessary.

Deciding whether you need a partner

As your business assesses opportunities, you collect and analyze a lot of information about the customer’s requirements and the competitors likely to bid against you. From that information, you establish win strategies, solution approaches, and price estimates. From that knowledge, you generate a list of required resources (for example, personnel, facilities, and equipment) and capabilities (such as staff skills, technologies, and problem solutions) that you need to have to win. But is your business equipped to provide these resources?

Use the SWOT analysis to assess your organization’s relative competitiveness as a solo bidder, as a prime contractor, and as a subcontractor. Honestly comparing your organization’s strengths and weaknesses with those of likely competitors (in relation to the customer’s needs and expectations) helps you identify potential partnering candidates that can neutralize your weaknesses and improve your firm’s chances of winning.

Selecting a partner

Select partners first on their ability to increase your chances to win and second on their ability to be a good team player. Find out whether the potential partner has worked with the customer successfully before, or whether they currently work with them. Make sure the potential partner wants to work with the customer and with you. If you’ve never worked with the potential partner before, ask an executive to reach out peer-to-peer for a preliminary discussion, and follow it up with other peer-to-peer discussions between the departments that will be involved in the bid.

When you’ve identified and vetted the best potential team members, you need to invite and convince each partner to join the team, in priority order. Contact the most appropriate decision maker or influencer and explain the rationale for having his organization on the team, its proposed role in the upcoming contract, and its responsibilities during the opportunity and proposal phases. Avoid detailed discussions of win strategies until the firm has committed to joining the team and signed a nondisclosure agreement.

Negotiating and documenting partnering agreements

Always thoroughly document the operational, financial, and legal aspects of the negotiated partnering agreement. The terms and conditions of the partnering and subcontracting arrangements need to be mutually acceptable — and perhaps acceptable to your customer. Partnering agreements need to be negotiated by officials with decision-making authority, reviewed and approved by your lawyers, and signed before you proceed.

Partnering agreements should include clearly defined

- Scopes of work, product or service specifications, and targeted work volumes

- Participation levels in proposal activities

- Allocations of proposal costs

- Confidentiality agreements, exclusivity clauses, and other legal liabilities and limitations

Most reactive proposals have a due date that you can’t miss, even by seconds. Remember, it’s called a deadline for a reason — and if you miss crossing that line, you’re dead.

Most reactive proposals have a due date that you can’t miss, even by seconds. Remember, it’s called a deadline for a reason — and if you miss crossing that line, you’re dead.