Chapter 9

Developing Your Proposal

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summarizing your offer for executives

Showing that you understand the situation

Addressing your customer’s stated, unstated, and implied questions

Expressing value, not just price

Establishing your qualifications

Making an active closing statement

A proposal must meet standards, whether it’s a reactive proposal (that is, a response to a Request for Proposal, or RFP) or a proactive one. If you’re responding to an RFP, you have to deliver the parts requested, in the order requested, to the specifications requested. If you’re writing a proactive proposal, you need to either follow industry standards or set your own. It’s best to follow standards because, frankly, they work.

In this chapter, we take you through all the parts of reactive and proactive proposals to help you develop bid-winning documents.

Crafting the Executive Summary

At the beginning of every proposal is the executive summary. Every proposal needs one. Every proposal without one will fail to reach the decision maker it must reach to win. Is that heavy-handed enough for you?

The fate of your proposal depends on the approval of the executive decision maker. From its very beginning, your proposal must convince key executives that you’re the answer to their needs. You have to show them that you’re in it for the long run and that you have their organization’s best interests at heart.

Knowing what an executive summary is

The executive summary is a concise, informational sales document-in-a-document. Its job is to convince your customer’s highest-ranking decision maker that your offer is superior to that of your competitors.

A compelling executive summary is good for evaluators, too. It helps them capture and digest the main messages in your proposal, which in turn improves your chances of winning.

Knowing what an executive summary isn’t

Despite its name, an executive summary isn’t a

- Road map to guide readers to what follows, although you can allude to the structure and thoroughness of your proposal

- Synopsis of your proposal’s main points, although you can highlight key aspects of your solution

- Retelling of your proposal, although it does achieve (in the language and brevity that executives appreciate) the same convincing argument that your proposal does

Focusing your message on your customer

Your executive summary focuses on your customer, not you. It sells your solution to your reader by demonstrating that you

- Grasp and can echo your customer’s vision and business issues

- Have aligned your own vision with that of your customer

- Understand the customer’s stated and unstated needs

- Have a solution that satisfies those needs

- Offer better financial and operational value than any competitor can

- Are the most qualified of all those angling to win the business

Use your customer’s name often — much more often than you use yours (a three-to-one ratio or a little better is about right). Address your customer directly, using the second person pronoun (you). Write as if you’re talking directly to the decision maker. Express how you

- Understand the customer’s motivation when considering a proposal

- Recognize and appreciate the customer’s hot buttons (those compelling reasons to buy, explained in Chapter 2, with more in Chapter 3)

- Have ensured that the solution satisfies each hot button

- Grasp that what truly matters are business benefits, not the features that enable them

Building a compelling summary

If your RFP provides instructions for your executive summary, follow them. If not, here’s the most effective approach:

-

Grab your customer’s attention.

Here are some options for connecting with a customer and showing that you understand its vision, its objectives for success, and the challenges it faces:

- Tell a true story that demonstrates the issues the customer faces.

- Quote a business leader’s expression of the organization’s vision.

- Cite a big number — a revenue target or potential liability — that demonstrates your understanding of industry issues.

- Provide a “look into the future” regarding the value your solution can bring within the context of the customer’s business.

- State your win theme and your “killer” discriminator — that thing you do that no one else can.

-

Explain how you clearly understand your customer’s needs or problems.

Use a bulleted list to make each hot-button need visible (for more on hot buttons, refer to Chapter 2). Prioritize each need or problem one by one from the customer’s perspective, using your customer’s words. Describe them in terms of the business pains they cause. For example:

- Do they make employees less productive?

- Do they anger customers?

- Do they allow revenue to slip away?

- Do they cause unnecessary expense?

- Do they harm the customer’s reputation?

If you’re the incumbent, indicate that you see how needs have changed since you started on the job and that your insider knowledge gives you the edge to solving them. If you’re the challenger, plant a seed that the old ways of handling these needs won’t suffice and that new perspectives are crucial.

If you’re the incumbent, indicate that you see how needs have changed since you started on the job and that your insider knowledge gives you the edge to solving them. If you’re the challenger, plant a seed that the old ways of handling these needs won’t suffice and that new perspectives are crucial. -

Describe your solution and how it solves each hot-button need.

This may be the most difficult part of the summary to write because you have to distill your solution into a very small space. A bulleted list is appropriate here, too. Here’s how to create one:

- Align your solution’s features to each of the customer’s needs, one by one, in the same order presented in Step 2. Stick to the major ones and only those that address the specific need directly.

- For each solution, state your solution’s benefits, followed by brief proof points to substantiate your claims.

- Be sure to indicate how the solution takes away the business pain you identified in Step 2. Consider showing how the future looks after your solution is in place.

- Express why each of these solution elements trumps the competition.

-

Clearly express your key discriminator.

This is the most important thing you do better than your competition. Point out this discriminator so your customer knows why it should choose you over your competitors, especially the incumbent (if it’s not you).

For more on key discriminators, turn to Chapter 6.

-

Ask for the business.

Indicate that you’re ready to act. Be as bold with this statement as the situation allows. At the very least, confirm your understanding of the next step in your client’s decision-making cycle. At most, you can ask for a meeting to discuss your solution or even finalize the deal.

For a model demonstrating this executive summary structure, see our template at the link we provide in the appendix.

Creating a good impression

Executive summaries may be all that decision makers ever read of your proposal. They are often the only pages a busy evaluator reads in detail before skimming through the other parts of your proposal. If you fail to show value in the executive summary, evaluators may jump to the price page and summarily dismiss the rest.

Your executive summary is like the finishing on a new house: If the molding fits snugly and the cabinets are perfectly painted, a buyer will likely think that the framework, roofing, and plumbing are equally fine. If your executive summary is professional and persuasive, reviewers will assume that the same is true of your solution and support. Make a good impression by

- Avoiding excessive boilerplate: Make sure every executive summary you write is unique to the opportunity. Solutions, client requirements, and competitors differ from one opportunity to the next. If you overuse boilerplate or “recycle” content from a prior proposal, your customers may think that you haven’t thought carefully about their particular situation and needs.

-

Making the summary visual: Include graphics to add emotional appeal and use a professional layout that makes the key points easy to see. Use them to reinforce your win themes and your discriminators (we address these elements from a number of perspectives in Chapters 2, 3, 6, and 7).

In these images (and your words for that matter), avoid excessive technical detail. Focus on benefits and clear discriminators. Illustrate the payback on your solution. If your financial story is positive, include “big-number” or summary pricing and savings.

In these images (and your words for that matter), avoid excessive technical detail. Focus on benefits and clear discriminators. Illustrate the payback on your solution. If your financial story is positive, include “big-number” or summary pricing and savings.

The executive summary, the cover, the transmittal letter, and the packaging are the most visible parts of your proposal. Each makes a strong contribution to the customer’s first impression of your offer, so your message and visuals must be consistent and compelling. For more techniques for creating visually appealing and persuasive proposals, see Chapter 11.

Writing a Transmittal Letter

A transmittal letter is how your proposal gets to the right readers. It’s a crucial part of any proposal because it allows you to start selling your solution before your customer opens your proposal. And although it comes first in your proposal package, it’s less important than the executive summary in the grand scheme of things (which is why we place it second in this chapter).

Write your transmittal in the form of a standard business letter and attach it to your proposal cover with a paper clip. If your submission is electronic, you normally write the transmittal letter as your transmittal email. It should be more formal than a normal email: Include a descriptive subject line, begin the email formally (Dear Ms. Smith:), and close with a formal signature block (your digital signature, name, company, title, and contact information).

The best transmittals introduce the opportunity, briefly describe the solution, and indicate the next steps. A great model for the transmittal letter is the standard marketing A-I-D-A format:

- A is for attention. Start your letter by reminding the readers why you’re sending the proposal. Include an RFP name and number if appropriate. Restate your proposal theme. Echo the enthusiasm that prompted your proposal.

- I is for interest. In your second paragraph, describe the readers’ problem or need in the briefest way possible. This piques the readers’ interest and pushes them to read the next paragraph.

- D is for desire or demand. Your third paragraph must convince your readers that they want your solution and that it satisfies their needs.

- A is for action. In your final paragraph, ask your readers to read and accept your proposal. You may also offer to meet at a certain date and time to discuss the proposal further and supply contact information to streamline the follow-up process. Some action sentences to consider include

- “I will call you on Friday to discuss next steps.”

- “Our team is ready to present our solution to your board next week.”

- “To meet the project deadlines and start achieving the benefits, sign the letter of intent today.”

Check out our sample transmittal letters (using the A-I-D-A format) in the link we provide in the appendix.

Describing the Customer’s Situation

Before you can solve a customer’s problem, you have to understand the situation — the environment where the problem occurs, the circumstances under which it occurs, and the root causes behind it. If you’re ready to write your proposal, you’ve already completed the preparation for this step (if you need help, refer to Chapter 6).

Unlike the executive summary and transmittal letter, which are key components of every proposal, the customer’s situation is a major component of a proactive proposal only. A customer’s RFP describes the current situation for you (and you should demonstrate that you understand that situation wherever you get a chance in your response). In a proactive proposal, however, you have to assure the customer that you understand its situation as well as, if not better than, it does.

If you’re responding to an RFP, your understanding of the current situation goes in the executive summary. If you’re writing a proactive proposal, you must place it in its own section. Believe this: The current situation may be the single most important persuasive element in your proposal. Don’t blow it off like there’s no use wasting time and words on explaining what the customer already understands — that’s not the point. The point is that you understand.

The following sections delve into how you demonstrate this understanding to your customer in a proactive proposal.

Setting up the scenario

You need to convince your customer that you understand the circumstances that have prompted your proposal. Don’t just recount the list of complaints that your customer shared with you. Although you want to describe the situation, using the customer’s actual words (see the next section “Expressing the problem and the pain”), you should also do the following:

- Express empathy. Say more than “we understand.” Instead, recap the customer’s vision and the obstacles to achieving that vision, and acknowledge the difficulty that led the customer to solicit your help.

- Mix in a bit of emotion. This is the argument element called pathos (refer to Chapter 2). A great way to bring some emotional appeal into your current situation is to talk about the specific pain the problem causes the customer.

- Add insight to what the customer already knows. You know the customer’s problems (refer to Chapter 3), so share your insights about them here. If you’re afraid that you’ll tip your hand and the customer may share your insights with the incumbent or a competitor, point to the issue and indicate that you’ve solved this kind of issue before.

- Indicate that you’ll customize your approach. Imply that the customer’s problem is unique, even if you’ve solved similar ones a thousand times before (don’t solve it yet; that’s for the next section of your proposal, which describes the solution you recommend — see the next section, “Expressing the problem and the pain”). This establishes a foundation for your persuasive arguments to follow.

Expressing the problem and the pain

Highlighting your customer’s needs and problems is a crucial part of your proposal, because you use them to prep the customer for your solution (which we discuss in the upcoming section “Writing the Solution for a Proactive Proposal”). Make the need or problem statements vivid and as meaningful to your customer as possible. Put them in a bulleted list, and structure your list as follows:

- Use verbal labels. Start each item with a label that concisely describes the need. Write them grammatically parallel — that is, write them as nouns or noun phrases, or maybe verb phrases that describe actions that the customer associates with the need. Just write them all the same way.

- State the cause. Follow each label with a brief statement of what you see as the root cause of the need or problem.

- Point out the pain. Complete the bullet point entry by describing the business pain resulting from the need or problem. Blatantly appeal to the reader’s emotions. Describe the pain in physical terms. Does the problem cause employees to work endless overtime, visibly dampening morale? Does the problem put quotas in jeopardy, reducing employees’ compensation and the business’s bottom line? Be as graphic as you can.

- Prioritize the list. Align your customer’s hot buttons (the customer’s most compelling reasons to act) with your list of needs, and prioritize them to match the importance your customer places on them. (Refer to Chapter 2 for more on hot buttons.)

Illustrating the customer’s environment

The best way to show that you understand your customer’s environment is to draw a picture that depicts what you know. Although most proposal writers fall back on describing the situation with words, measures, and specifications, pictures can be more effective. Here’s why:

- They show that you’ve taken extra care to understand the situation. Drawing or even photographing the customer’s current environment shows that you’ve put in extra effort to get to the bottom of the customer’s problem.

- They reduce the amount of content you have to write. The old adage is right: Pictures do convey more than words. And in proposals, they reduce the amount of detail you have to describe. You still need to write a caption and add references to the images in the text, but you can drastically cut down your verbiage by using images.

Illustrations are so important that we look at them in more detail, including how you can use them in every part of your proposal, in Chapter 11.

Describing problems in the customer’s own language

Proposals are all about your readers and their problems, so every word you write in this section needs to apply to your customer alone. A great technique for letting your readers know that you understand their point of view is to echo the very words they use to describe their problems. Nothing says “I get what you said” better than using the exact terms that your customer uses to describe work through scenarios and operational, technical, and managerial problems.

Answering Your Customer’s Questions

Now we come to the solution part of your proposal, and again we must differentiate between the way you describe your solution in an RFP response versus how you do it in a proactive proposal. Most RFPs essentially provide a list of your customers’ questions. And proactive proposals basically answer the questions you think your customers have about your solutions, your methods, and your qualifications. So for a proactive proposal, you have to ask yourself the same questions your readers would have asked you. And for both types of proposals, you need to think beyond the customers’ simple questions to the unstated questions that lie behind them. Thinking through the stated questions helps you uncover the unstated needs we talk about in Chapter 4. Here are some examples of questions you may hear (the stated needs) and the possible underlying questions that provide insights into unstated needs:

- How will this work in my world? Your staging facility is great, but I’m unique, and you can’t anticipate my situation and its problems.

- Who will do what work? And why can you do it better than I could myself?

- How much will it cost? And how much will I save, now and in the future?

- How can I pay for it? And can I still make money if I buy it?

- Why should I do this now? Right now, instead of when the economy is a little more robust?

- How have you done this before? Have you done it for someone as individual as I am, or a company I admire?

- Why shouldn’t I stay with the incumbent? They’re good people; why do you think you’ll do better than they have?

- How will you stay on schedule and budget? And how will you prevent scope creep (and it always happens with guys like you)?

The following sections explain how to express your solutions: First, in response to questions from a customer’s RFP; second, anticipating the customer’s questions as you write a proactive proposal; and third, making sure your solution discussions echo your win themes. And although we separate the approaches for your convenience, each approach has insights that may help you with the others.

Responding to an RFP’s questions

What’s the best way to answer the direct questions in your customer’s RFP? Clearly, directly, and succinctly. Easier said than done.

You want every response to

- Express that you comply with the requirement

- Explain how you comply and why your way is the best way

- Answer your customer’s questions

- Address your customer’s hot buttons and echo your win themes

To help you craft these winning responses, we provide a four-part RFP question-response model for all proposal writers to follow on every deal. Table 9-1 shows the response elements and defines the content that goes in each.

TABLE 9-1 Four-Part RFP Question-Response Model

|

Question Element |

Description |

|

Restatement (topic) |

Restate the customer’s questions in your own words and indicate whether you comply, do not comply, or partially comply. You can enhance your response with a brief value proposition, starting with the preposition by. |

|

Brief answer (comment) |

In a sentence or two, describe your solution to the problem or tell how you’ll fulfill the need. Make this the kernel of your response; if evaluators have only ten seconds to review each answer, make sure they’re assured that you comply and that your response supports one of your proposal themes (refer to Chapter 2) or your overall proposal strategy (refer to Chapter 6). |

|

Expanded answer (comment) |

For complex questions, use this element to elaborate on, illustrate, and explain your brief response. Add whatever is necessary to fully define what your solution element does and how it works within the customer’s environment. |

|

Payoff statement (point) |

Give the evaluators a key takeaway for this response. Express how this element addresses a hot button, helps support other requirements, supports a win theme, or brings a significant benefit to the customer. |

Answering the questions plainly

Some proposal writers weave and bob like a prize fighter. You read their responses to what seem like simple enough questions (okay, they’re hard questions but simply stated) and marvel at the evasive tactics. They hedge. They dodge. They redirect to something they find more comfortable to talk about. And they never answer the question. And what does that do? It either disqualifies them for being nonresponsive or prolongs the RFP process by requiring a clarifying stage after all the proposals are submitted.

Linking your answers and win themes

In the earlier section “Responding to an RFP’s questions,” our RFP response model described two places where you can link win themes with your individual responses to your customer’s questions. Every answer affords you an opportunity to reinforce your win themes, but don’t limit your win themes to your answers. You can’t really overdo this, so look for every opportunity to repeat appropriate win themes wherever you can, such as the following:

- Volume, section, and subsection introductions: Since RFPs usually group questions under categories, address how all the responses in the section support your win themes (provided that the RFP allows you to do this).

- Graphics that depict your solution components: You can illustrate your win themes within images you include to support your answers. See Chapter 11 for ways to do this.

- Captions that support your graphics: These captions echo a win theme as you express the action depicted in your image (see Chapter 11).

Writing the Solution for a Proactive Proposal

Writing the solution section for a reactive (RFP response) or proactive proposal is mostly a matter of answering questions about how you’ll solve the customer’s problem. Although it’s more direct if you’re responding to an RFP’s questions, you can follow the same approach in your proactive proposals. You just need to create a structure that simulates how your customer thinks.

The following sections show you how to use the questions you believe your customer may have asked in an RFP to write a proactive proposal with a comprehensive portrayal of the work you will do.

Developing a structure that’s easy to understand

The questions you need to answer as you’re writing the solution for your customer are actually pretty simple. Of course, every answer prompts a new question, so you need to think about your particular customer’s needs as you flesh out your solution description. And, for that matter, every main and follow-up question includes an unstated question — “Is what you say true?” For every claim you make as you answer your customer’s questions, you need to provide proof that your claim is valid.

If your solution is complex (composed of multiple products and services, or extensive support processes), you will probably have to answer the main questions (and provide proof statements) multiple times. Your need to fully explain that each solution building block is supported by this approach’s inherently modular, question-based structure.

To explain a solution fully, you need to answer four key questions (and a number of follow-ups) from your customer’s point of view:

-

What is it? Define your solution and the products and services that will deliver it. Although you can define your solution a number of ways, a classical definition works well because it places your solution into a class or category of similar solutions and then differentiates yours from everyone else’s, as you see in this example:

-

SureGuard 2.0 is a wireless security system that lets you secure your business from intruders while monitoring and controlling your system from any wireless phone or tablet.

SureGuard 2.0 is a wireless security system that lets you secure your business from intruders while monitoring and controlling your system from any wireless phone or tablet.

Anticipate follow-up questions like these:

- How is it different from what we have or what you used to offer?

- How is it better than what we have or an alternative?

- How is it especially appropriate?

- What discriminating benefit does it provide?

As an example:

As an example:- Unlike previous versions, SureGuard 2.0 allows you to view your premises in real-time through webcam feeds while capturing the recordings for later playback. No longer do you have to be on premises to activate or deactivate your system — all functions are available through your iOS or Android device. It’s especially valuable for enterprises like yours that hold large sums of money after normal hours of operation.

-

- How does it work? Describe — better still, describe and show — the way your solution will work in the customer’s environment. Use one of a variety of schematic, conceptual, or metaphoric graphics to illustrate the inner workings of the solution. If you illustrated the customer’s current situation, use a similarly styled illustration to show the same scene after you’ve implemented your solution. Answer follow-up questions such as

- How does it “fix” the problem?

- What are its functional components?

- How do these components work with existing workflows and infrastructure?

- What technology supports the solution?

-

What will it do for me? Identify and describe the benefits the customer will realize. Now is the time to link individual, specific customer needs with the individual features your solution uses to bring the benefits that will help your customer achieve its business goals. As you craft your benefit statements, anticipate follow-up questions like the following:

- How does that aspect of your solution deliver this particular benefit?

- What immediate benefits may we receive?

- What long-term benefits can we expect?

- How will this solution anticipate future needs?

In Chapter 7, we present a lot of information about features and benefits: What they are (features are the what of your solution; benefits are the so-what), how they relate, how to tell the difference between them, and how benefits are central to your proposal argument. Earlier in this chapter, in the section “Describing the Customer’s Situation,” we indicate that you need to create a parallel structure between the problems and needs you describe in the current situation and the features and benefits that solve them in your solution. And now we add the element of proofs: providing supporting evidence that your solution will do what you claim.

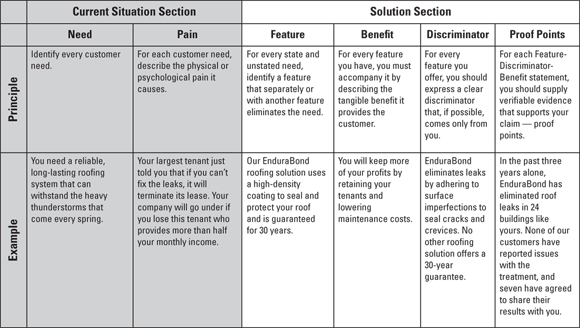

One way you can pull all these interrelated elements together as you answer the “What will it do for me?” question is to present them in a table. Figure 9-1 shows the formula for displaying Need-Pain-Feature-Benefit-Discriminator-Proof statements in an easy-to-scan table.

Formatting options abound when you’re assembling your Need-Pain-Feature-Benefit-Discriminator-Proof statements. If your statements are relatively simple, you can use the table format from Figure 9-1. If you have complex needs, multiple pains, extensive advantages, comprehensive benefits, and significant proofs, you may need to create short subheadings to introduce each and treat them thoroughly. Usually, you can create a bulleted list and align each statement with the needs you list in the current situation section. You don’t have to repeat the need, but if your proposal is longer than a few pages, it’s good to remind the reader of the issue that prompted the solution element.

-

How will you implement it? Spell out who does what and when. Explain in detail your method for getting the solution up and working for the customer. Use project management tools like a Gantt chart to illustrate how the project will go (we talk about Gantt charts and tracking progress in Chapter 8). Name and justify the key personnel who will deliver each solution component. Anticipate these follow-up questions:

- How will you do the work?

- Who will provide and maintain the service?

- Why did you choose these people to work on our problem?

- Why is your method better than the competition?

- What will happen next?

For many businesses, the “How will you implement it?” response is a major section, chapter, or even volume of a proposal, known as the methodology or scope of work. As with the cost question, it’s all a matter of degree: The more intricate and expensive your solution, the more detail you should supply.

For many businesses, the “How will you implement it?” response is a major section, chapter, or even volume of a proposal, known as the methodology or scope of work. As with the cost question, it’s all a matter of degree: The more intricate and expensive your solution, the more detail you should supply.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 9-1: The guiding principles behind Need-Pain-Feature-Benefit-Discriminator-Proof statements (and an example of each).

Creating a vision of the outcomes you’ll provide

The solution section of your proposal is all about getting the customer to believe in your version of its vision. You have to align your solution to match the customer’s vision, and should your solution not align with this vision, you must provide sufficient evidence as to why altering its vision may be advantageous.

Once again, the best way to confirm this alignment is by illustrating it. Graphics powerfully demonstrate that you “get” your customer’s vision and that your vision aligns. The graphics in your solution section influence the following:

- Credibility: People equate visual design with professionalism.

- Receptivity: Readers tend to absorb the main points faster when viewing images versus text.

- Stickiness: Readers recall information more readily when it’s presented through or with images.

- Responsiveness: Images trigger emotional responses better than words and, as a result, are more persuasive.

Creating a comprehensive visual strategy that reinforces and enhances your textual messages is a wonderful way to ensure that your readers stick with your solution story and your story sticks in their minds. Recall that “before-and-after” images influence people to start life-changing diets and workout regimens. Use the same approach to show what needs to be changed and how it will change after you deliver your solution. Seeing truly is believing (even if it’s not real yet).

Establishing Value in the Pricing Section

Presenting your pricing is a major issue in most proposals. Pricing is tough because it’s the “bad news” that goes along with the “good news” of your solution. But it’s also the most anticipated part of your proposal, so you have to provide the bad news in context with the good news. When expressing pricing, you answer a simple customer question: “How much does it cost?” And you need to anticipate your customer’s follow-up questions, such as these:

- What’s the bottom line?

- Why is this more (or less) than your competitor costs?

- How does this price compare to what I’m paying today?

- When can I expect positive returns?

In other words, your customer wants to know what value it’s receiving for this price. This section discusses how to answer your customer’s pricing questions and quantify your answers with hard data.

Expressing the value of your solution

Customers scrutinize your pricing section more than any other. That’s no deep insight, we know. Every decision ultimately boils down to money. But a proposal writer’s job is to present the price within the context of value. To do this, you have to

- Clearly state value propositions that encapsulate the benefits, discriminators, and win themes you’ve stated elsewhere in the proposal (refer to Chapter 6 and the next section for more on the relationship between win themes and value propositions and Chapter 7 for more on benefits).

- Illustrate the difference between cost and value by providing graphs and pictograms to help highlight your value and show the return that a price will yield.

- Provide only the level of pricing detail your customer needs to decide in your favor (or they won’t see the forest for the trees).

We explore these three key elements of pricing in the following sections.

Stating your value proposition

In Chapter 6, we urge you to write clear win themes — key messages to your customer about the value you bring to individual aspects of the solution. We state there that some proposal writers refer to these messages as “value propositions.” Here’s why: While your win themes reiterate value throughout your proposal, in the pricing section, they directly address how aspects of an offer (and the corresponding price for those aspects) can positively affect the customer’s business. Well-written value propositions have to describe tangible and quantifiable value because your pricing is now a looming reality to the customer. Your value propositions must clearly show how the price of the solution is offset by the tangible value it brings.

In your pricing discussion, create value propositions to provide a focal point for your solution and its tangible benefits for you and your customers.

You will [solve/improve/reduce] your [problem/need] by [time/method qualifier], because our [solution/technology/feature/method] [delivers/provides/supplies] [new capability/problem resolution] for [price/price comparative].

Think about the variables in brackets: They cover the need, the methodology, the outcomes and benefits, the solution, and the cost all in one sentence. In a nutshell, a one-sentence value proposition summarizes the worth of your offer, from end to end.

You will reduce your high turnover rates by 30 percent, because our employee assistance program supplies one-on-one counseling for a manageable, usage-based fee.

- Expanding it to describe both tangible and intangible value

- Adding a variable to show how your solution is a better alternative

- Describing how aspects of your offer positively affect your customer’s business

- Stating priorities and timelines to reinforce your value

When building your value proposition, be sure to avoid the following:

- Expressing a one-size-fits-all solution

- Boasting with phrases like “we are the leader” or “our world-class solution”

- Overselling features without properly describing their benefits

- Building confusing, complex, hard-to-remember statements

Start your pricing section with your value propositions. Follow them with a recap of your most compelling Need-Pain-Feature-Benefit-Discriminator-Proof statements, before you even bring up the subject of money.

Using graphics to clearly show value

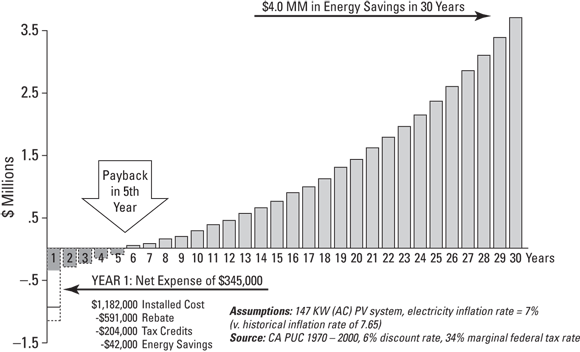

A graphic can help persuade your customer that the value you claim truly exists. Using a graph or chart to show the return on investment (ROI) or the payback period on your project is a great way to cement the idea of value. It succinctly reinforces your value proposition and sets the context for the price your customer will pay. Figure 9-2 provides an example that shows how quickly a customer can recoup its investment.

Source: APMP Body of Knowledge

FIGURE 9-2: Illustrate the value you offer by using a suitable chart.

For more information about persuading with graphics and other visuals, see Chapter 11.

Summarizing your pricing information

Your proposal will likely be assessed by many reviewers with differing perspectives. The pricing section is no exception. It will be an early target for an evaluator, who will then pass it along to the financial analyst to “crunch the numbers” and verify the value you’ve claimed. Providing a summary of your pricing detail (in a spreadsheet or table or in a list of item pricing that you can supply in an appendix) makes an evaluator’s job easier. It also gives the pricing analyst a simple and quick view of the price, which can speed up comparisons.

- Total price in narrative and graphic form (many customers want to see the bottom line upfront)

- Pricing assumptions (just the major, most important ones)

- Overall themes (that echo your value proposition)

- Price discriminators (value you offer that no one else can)

- How you logically established your prices (and any positive price implications of choosing that approach)

- Any cost tracking and control systems that will benefit the customer further down the line

The pricing summary should tie together details readers will see in the detailed pricing sheets. It should also include your assumptions and estimating guidelines, which will likely need to be tailored from previous programs. Reviewers like to see traceable details as well as summaries of data. An easy-to-review yet detailed pricing reference gives evaluators a reason to award the bid to you.

Quantifying your claims with data

The pricing section can be an argument-clincher by showing that you can do what you say and that you have the facts and the rationale to back up your claims. Your facts not only validate what you’re claiming and lend credibility to your organization, but they also provide you and your customer with the details necessary to make informed decisions about your price. And even though price is market-driven, the facts help you build a story that creates confidence in your solution.

You can justify and build your case for your costs by demonstrating that you’ve done the work before at a certain cost. This is where what proposal people call “past performance” comes into play (you find more about this in the next section). Nothing is more compelling than data showing how you’ve already performed the work the customer wants done. You may have completed entire projects similar to what your customer needs, so you can fully substantiate your price with verifiable, historical data.

Building the Experience Section

Just as you’d prefer a surgeon who has successfully performed thousands of operations just like the one you need, customers prefer to do business with companies that can demonstrate that they have both experience that is relevant to the work they need done and a track record of success. You write the experience section (sometimes called the qualifications section) to recount relevant know-how and past performance to provide proofs that are hard to argue against.

The following sections help you figure out what to include in this key background information.

Documenting your team’s know-how

Have we mentioned that proposal writing is mainly answering a lot of questions? Here’s another one: “Why us?” That is, why should your customer choose you over all other vendors? One great answer is, “our people.” Although many companies say their people are their greatest asset, a proposal writer has to prove it. And if you can, you can win.

Depending on the type of business you’re in and the scope of work in the projects your people perform, you may want to create professional résumés for individuals on your team that highlight their skills, experience, education, and accomplishments. If your company works on major projects, you may need résumés as extensive as, if not more than, traditional job résumés. These may include content categories like Experience, Education (especially technical), Certifications, Awards and Recognition, and Professional Memberships. You need to tailor these résumés for the specific proposal you’re writing. Tailor them by rearranging the content to highlight recent projects that match the size, scope, and solution of the current opportunity. You can also include client commendations and even prior work for the customer, if pertinent.

If your proposals are less formal or less complex, you can avoid the full-blown résumé by creating short paragraphs that highlight the knowledge, skills, and experience of your key team members.

David Michaels is the senior project manager we have assigned to direct your project. David has been our most highly sought-after project manager for the past 12 years. He is certified as a Project Management Professional and a licensed electrical engineer. David successfully led the Regional Airport facility upgrade, a project of similar scope and intricacy to yours.

Choosing relevant past-performance examples

The other question customers ask about your qualifications is, “Who else have you done this for?” You want to respond with relevant experience. Relevant experience is simply comparing how you’ve performed on previous jobs that match the goals, size, scope, and complexity of the new opportunity.

In general, make sure you answer the evaluators’ basic question: “Did you do what the contract required?”

- Customer name

- Project or contract name

- Dates of the project and term of contract

- Customer project lead and contact information

- Customer’s industry

- Project description (nature of the work performed, number of sites, amount of equipment, types of services)

Some customers may place greater importance on past performance than others. But no matter what the setting, clear descriptions of past performance can help build confidence in your solution and ability to perform. Always present your past-performance descriptions in an attractive, easy-to-understand way, using graphics and proof points as appropriate.

Many RFPs ask for references, and may insist on speaking directly with any companies that you list. Keep an archive of selected customers and customer contacts and ask for permission to use them as references. Help prepare them by supplying a list of questions they can expect to hear, such as “How well did the bidder work with your managers?” and “Did the bidder adhere to its implementation schedule?”

Closing with a Call to Action

In this chapter, we trace the structure of a proposal from beginning to near-end. And you may notice that the experience section, though of significant importance to the customer, may not be the most exciting section to read. You don’t want to end your proposal on a low note, so how do you finish well?

- Restate your value proposition.

- Recap your customer’s hot buttons and your solution’s benefits.

- Reinforce the need to act now.