CHAPTER 21

The Economics of Global Agreements

21.0 Introduction

This books ends where it began, with a focus on climate change. The reality of global warming burst into human consciousness just 30 years ago, suddenly and at a scale dwarfing the local and regional pollution problems that defined the twentieth century. Incredibly, the human ecological footprint is now disrupting the entire planet’s climate control system. Even if we manage to hold warming to the low end of 4 degrees F, still we will have pushed the earth into a climate that is fundamentally different from the one that has supported human civilization for the last 10,000 years. In the coming decades, human-induced global warming will challenge both humans’ adaptability and the survival of perhaps half the species on the planet. Mitigating and adapting to climate change will be the work of your generation.

Since our early introduction to climate change, we have explored four difficult, but general, environmental economic questions. The answers to these questions can help us address the global warming challenge. First, how much pollution—in this case, global warming—is too much? We considered three broad answers to this normative question: efficiency, safety, and ecological sustainability. Efficiency advocates would have us carefully balance the very real costs of slowing global warming against the obvious benefits. In contrast, both safety and ecological proponents find benefit–cost analysis too narrow a basis for choice and advocate immediate rollback of carbon dioxide emissions, despite the cost.

The second issue is, what are the obstacles to effective governmental action in achieving our goals? Suppose that we set a target to cut carbon dioxide emissions 25% by 2020? Are we in fact likely to get there? Government policymakers are hampered by imperfect information. In addition, the possibility of political influence over environmental policy emerges when regulators must make discretionary choices. Our 40-plus-year experience with environmental regulation indicates that ambitious pollution reduction goals have proven difficult to achieve. Enforcement in particular has proven a weak link in the regulatory chain.

Our third question: how can we do better? The book suggested two possible answers: (1) smarter regulation and (2) a shift in government focus to the promotion of clean technology. Incentive-based regulation carries the promise of reducing pollution in a more cost-effective and technologically dynamic manner than the current reliance on command-and-control methods. In the greenhouse case, this means that carbon taxes or marketable permit systems can help us achieve our goals at lower cost than mandating particular types of carbon dioxide emission-reduction technology.

In addition to better regulation, the government can initiate a proactive policy promoting the rapid development and diffusion of clean technology. To qualify as clean, a technology must be cost-competitive, either immediately or after only a period of subsidy. If the government follows this selection rule, the policy of promoting clean technology will also be cost-effective. Clean technologies with substantial power to reduce carbon dioxide emissions include energy efficiency, solar power, wind power, and electric vehicles, all combined with battery storage.

Here is the fourth and final question: Is an effort to combat global warming consistent with the need for sustainable development in poor countries? On the one hand, boosting the incomes of the poor majority of the planet in order to raise billions of people out of desperate poverty, increase food security, and ultimately reduce population growth rates might work against the goal of emission reductions in the short term. Yet, consumption by the poorest half of the planet’s inhabitants is not the main greenhouse problem. Moreover, reduced population growth is a vital step in any program to control global warming. At the same time, promotion and diffusion of sustainable technology, and greater efforts to conserve forest resources, will directly reduce emissions.

This chapter of the book considers one last and formidable obstacle toward progress in global environmental issues such as slowing global warming: the need for coordinated international action. Because carbon dioxide pollution arises across the globe, no one country can solve the global warming problem. International action, in turn, will result only from effective international agreements. Such agreements are unfortunately hard to achieve and, once reached, can prove difficult to enforce.

We begin by analyzing the incentives that a nation has, first to join an international pollution-control agreement and second to comply with the terms of that agreement once it is signed. We then turn to a discussion of the tools available for enforcing such treaties. The chapter then moves on to analyze two international agreements: one on ozone depletion and the other on biodiversity. We end by coming full circle with a consideration of the prospects for an effective treaty to halt global warming.

21.1 Agreements as Public Goods

Effective international agreements are hard to develop. The basic problem is that agreement on burden sharing is difficult to achieve. In principle, each country might contribute its true willingness to pay for a treaty. This willingness to pay in turn would depend on both the benefits received and the ability to pay, which might vary widely between nations. For example, low-lying Bangladesh and Egypt have a tremendous stake in slowing global warming and preventing sea-level rise. Yet, both countries are poor and would have a difficult time financing strong measures to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. On the other hand, a wealthy country such as Germany has a high ability to pay but may have fewer immediate interests at stake.

A poor country’s willingness to pay to join an agreement will typically be much smaller than a rich country’s, simply because it has a much lower national income. Yet, poor-country participation is often vital. For example, if India industrializes further, using its vast coal reserves, global warming will accelerate considerably. Given India’s low willingness to pay for a reduction in global warming (as a result of its low income), a compensation fund would have to be established for India to sign a greenhouse treaty. Those with a high willingness to pay (typically rich countries) would have to pay to help India adopt, at a faster pace than the nation already is, less-polluting and less-costly energy sources. Otherwise, it would not be in India’s interests to sign the treaty.

If each nation did contribute its true willingness to pay, then the agreement process would generate an efficient level of global pollution control. However, a country’s underlying willingness to pay for an agreement is not well defined in the first place and is certainly not transparent to negotiators from other nations. Therefore, each nation’s bargainers will have an incentive to understate their true interest in a treaty in the hopes that others will shoulder more of the burden. In the extreme, a country might not sign a global warming or other environmental treaty at all but still benefit from the efforts of other nations.

This is just another form of the free-rider problem we have encountered several times in the book, beginning in Chapter 3. From an economic point of view, an international pollution-control agreement is a public good, which has to be provided voluntarily by the private nations of the world. Reducing global warming is a public good, because there is no way to exclude free riders from enjoying the benefits provided by the treaty.

The public good nature of environmental treaties has two implications. First, treaties will tend to be too weak from a benefit–cost point of view, as signatory nations are reluctant to reveal and commit their true willingness to pay in the bargaining process. Second, once signed, nations will have a strong incentive to cheat on the agreement. Unilateral cheating is another way to free ride on the pollution-control efforts of others. Of course, if everyone cheats, the agreement will collapse.

While the theory of public goods predicts that international environmental treaties will be both weak and susceptible to enforcement problems, agreements nevertheless do get signed, and efforts are made to ensure compliance. Table 21.1 lists some of the most significant environmental treaties now in effect.

TABLE 21.1 Global Environmental Agreements

| Formal Name (Common Name) | Year Signed | Prominent Nonmembers, 2010 |

| The Antarctic Treaty System | 1959 | Self-limited membership |

| Nuclear Test Ban Treaty | 1963 | France, China |

| The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES Treaty)a | 1973 | |

| New Management Procedure of International Whaling Commission (Whaling Moratoria) | 1974 | Japan |

| Law of the Sea (not currently in force) | 1982 | United States, United Kingdom, West Germany |

| Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol) | 1987 | |

| The Basel Convention on Trans- boundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (Basel Convention)b | 1989 | African nations |

| Kyoto Global Warming Treaty | 1997 | United States |

| Rio Convention on Biodiversityc | 1992 | United States |

Treaty websites: www.cites.org/www.ats.aq.

awww.wcmc.org.uk/CITES.

bwww.ban.org.

cwww.biodiv.org.

21.2 Monitoring and Enforcement

In Chapter 3, we noted two ways to overcome the free-rider problem: government provision of the public good and social pressure. Within a single country, government typically supplies the public good of environmental protection, using its ability to tax, fine, and jail to prevent free riding (pollution) by private individuals and corporations. In the United States, for example, environmental laws are passed by Congress, and the regulatory details are then worked out and enforced by the Environmental Protection Agency and the Justice Department.

At the international level, the treaty is the equivalent of an environmental law. However, no international government exists that coerces nations into undertaking the broadly agreed-upon steps, nor is there likely to be one soon. The United Nations has no authority over its member nations in the environmental arena. Nevertheless, each treaty does set up its own intergovernmental organization (IGO), which is charged with overseeing the agreement. Countries seldom agree to give IGOs the authority to actually enforce treaty agreements; this would be giving away too much sovereignty. However, IGOs can still be given substantive powers. One of these is to set nonbinding standards that states are “expected” but not required to meet. The second is to monitor compliance with agreements.

For example, under the Antarctic Treaty, an environmental committee has been appointed to which each nation must submit information on its management procedures. Environmental impact statements (see Chapter 8) are also now required for new activities, including tourism, sponsored by a member nation. Social pressure can then be brought to bear on states that either fail to achieve the standards or are out of compliance with the broader terms of the treaty. The environmental group Greenpeace has effectively “shamed” countries with particularly poor environmental records on the continent.

Such social pressure is the second way in which free riding has traditionally been controlled. However, a well-orchestrated public relations campaign encouraging the United States to join with the “community of nations” was insufficient to get it to sign a biodiversity treaty. Such moral pressures are even less likely to be effective in ensuring compliance once treaties have been signed. Nevertheless, bad publicity and community pressure, as in the Antarctic case mentioned earlier, remain among the important tools of international negotiation.

Given the lack of an international pollution-control agency, and the limited effectiveness of social pressure, the burden of enforcement will fall on measures written into the treaty itself. Treaty members must agree in advance on the sanctions to be levied against noncomplying members or nonmembers. In the absence of such sanctions, compliance is liable to be very poor. For example, the CITES treaty regulating trade in endangered species relies primarily on national enforcement efforts. According to the World Wildlife Federation, an environmental group that voluntarily monitors CITES, about one-third of the member nations have never filed the required biennial progress report. Most nations that do report have done so in a very tardy manner. The basic problem is a lack of committed resources. Even in a rich country such as the United States, a lack of trained customs officials means that up to 60,000 parrots have entered the country illegally in a single year.1

There are two basic enforcement tools: restricting access to a compensation fund and imposing trade sanctions. The simplest mechanism is to establish a compensation fund to act as a carrot for both joining a treaty and complying with its terms. Such compensation funds, however, can induce compliance only by poor countries as high-income countries are the ones who contribute to the fund. Trade sanctions are the most powerful tool available. As we shall see, their mere existence played an important part in the success of the agreement to control depletion of the ozone layer. Sanctions tend to be restricted to goods related to the treaty. This is useful, as it minimizes the possibility that the imposition of sanctions for enforcement purposes will degenerate into a trade war. For example, under the CITES treaty, a ban on trade in wildlife products from Thailand was imposed to encourage that country to crack down on illegal exports. Many environmental agreements authorize some form of trade sanction.

21.3 The Ozone Layer and Biodiversity

This section examines two environmental treaties: the 1987 Montreal Protocol to control the depletion of the ozone layer and the 1992 Rio Earth Summit agreement on biodiversity. We focus on the factors that promoted agreement and the enforcement mechanisms built in. In the ozone case, we also have a compliance record to examine.

OZONE DEPLETION

The earth’s upper atmosphere is surrounded by a thin shield of a naturally occurring chemical known as ozone. Ozone at ground level is better known as smog and is quite harmful. By contrast, the ozone layer surrounding the earth serves a beneficial role by screening out the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. Exposure to ultraviolet rays causes skin cancer and eye disease, reduces the productivity of agriculture, and can kill small terrestrial and marine organisms at the base of the food chain.

The ozone layer is threatened by the buildup of human-made chemicals in the upper atmosphere. These chemicals, known as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), were invented in the 1940s. They have since served as aerosol propellants, coolants in refrigerators and air conditioners, foam-blowing agents, and gaseous cleansers for medical and computer equipment. They are also very long-lived stock pollutants. CFCs released into the atmosphere from discarded refrigerators today will continue to break down the ozone layer for up to 100 years.

The potential for significant ozone depletion by CFCs was first established in 1974. Despite the serious health and ecological effects of ozone depletion, uncertainty about the scientific link between depletion and CFCs slowed international regulatory action. Although the United States unilaterally banned CFCs as aerosol propellants in 1977, few other countries followed suit. In 1982, a benefit–cost analysis published in the prestigious American Economic Review, while acknowledging substantial uncertainty, argued against regulating CFC use on efficiency grounds.2 This position was also advanced by CFC manufacturers.

Nevertheless, international concern over the problem was mounting, fueled by a 1985 British study documenting a huge, seasonal ozone hole over Antarctica. Less severe, but measurable depletion was occurring throughout the middle latitudes. In 1987, building on 6 years of United Nations’ efforts, 24 countries signed the Montreal Protocol to Protect against Atmospheric Ozone Reduction. Just after the protocol was signed, a conclusive scientific link between ozone depletion and CFCs was at last established.

The treaty called for a 10-year, 50 percent reduction in CFC production by each country from a 1986 baseline. The treaty made some concessions to poor countries, which would otherwise be locked into current levels of low consumption and were hardly responsible for the global problem in the first place. Developing countries were given a 10-year grace period before cutbacks would have to be made. In addition, rich countries were urged, but not required, to set up an assistance fund to ease the transition.3

These incentives were insufficient to attract India and China, both of which viewed the benefits of cheap refrigeration from CFCs as too high to forgo. As a result, a 1990 revision of the Montreal Protocol required rich countries to establish a fund of $260 million to finance the adjustment to CFC replacements in poor countries and that $60 million was to be contributed by the primary CFC producer, the United States. This fund provided a sufficient inducement for most of the remaining nonmember countries to join, including India and China.

As a way to discourage free riding by nonmembers, the treaty mandated trade restrictions on CFCs. Parties to the treaty were required to ban imports and exports of CFCs, many products containing CFCs, products produced with CFCs, and technologies for producing CFCs to nonmember countries. These trade sanctions limited the gains from nonmembership and thus reduced free riding.

The half-dozen companies that produce the great bulk of CFCs worldwide ultimately supported the 1987 Montreal Protocol, although they viewed the goal of a 50 percent reduction as greater than necessary. But, by 1988, faced with mounting evidence of ozone depletion, the major producer DuPont announced its intentions to phase out CFCs altogether by 2000. In 1990, the Montreal Protocol nations also revised the treaty to call for a complete ban by 2000. In 1992, after a finding that an accelerated phaseout might save an additional million lives through reduced skin cancer, the treaty nations agreed to eliminate CFC production by 1996. The compensation fund was also boosted to $500 million.

Compliance with the early terms of the treaty by the rich countries was quite good; the accelerated phaseout adopted in 1992 was possible because several nations were already ahead of schedule. As discussed in Chapter 16, the United States adopted an incentive-based regulatory approach—tradeable permits combined with indirect pollution taxes—to meet its treaty obligations. Developing countries made good on their commitments as well. The compensation fund in particular has been credited with helping China meet its mandated targets. By 2016, 98 percent of CFC and related chemical production had been eliminated.4

The first two sections of this chapter suggest, on theoretical grounds, that the prospects for obtaining enforceable international agreements on the environment were not good. In many ways, the Montreal Protocol contradicts such a gloomy picture. Despite scientific uncertainty, initial international agreement was obtained. The threat of trade sanctions helped overcome the free-rider problem. A sufficient compensation fund was eventually established to bring poor countries on board. The pollution-control target was dramatically tightened as scientific knowledge advanced, and compliance has been remarkably good.

Several factors help explain the success of the Montreal Protocol. The dramatic discovery of the ozone hole over the Antarctic provided an initial boost to the treaty process, as did findings of a comparable arctic hole in 1992. Once the agreement had been signed, however, two additional factors worked in its favor. First, because only six main corporations were involved in the production of CFCs, monitoring the progress of the CFC phaseout has been relatively easy. Second, clean technological substitutes for CFCs have developed quickly as a result of the imminent ban. Early predictions of prohibitively high compliance costs proved faulty.

To sum up, the Montreal Protocol has proven to be a stunningly successful environmental treaty. Beginning with initial meetings in 1980, through the 50 percent cuts agreed to in 1987, and the accelerated phaseout decided on in 1992, it took “only” 16 years to effectively ban the production of CFCs. By 2010. the Antarctic ozone hole had stopped growing, and it should fully repair itself by around 2050.5

BIODIVERSITY

Protecting biodiversity means protecting endangered species—not only cuddly mammals but also the entire ecosystems in which they live. As we discussed in the previous chapter on deforestation, preserving the stock of genetic material found in natural ecosystems is important not only for its existence value but also for two utilitarian reasons: pharmaceuticals and agricultural breeding. As an example, a strain of wild Mexican maize had a natural immunity to two serious viral diseases. Hybrid corn seeds based on the genetic material in the maize are now available from U.S.-based seed companies.

The fact that Mexico received no compensation for this profitable innovation helps explain why the valuable resource of biodiversity is threatened.6 Historically, genetic material has been viewed as an open-access, common property resource. Seed and drug companies based in rich countries would send prospectors to tropical countries that are host to the vast majority of the world’s species. (A single tree in an Amazon rain forest contained 43 species of ants, more than in the entire British Isles!) The prospectors would return with samples to be analyzed for prospective commercial uses. If a plant or animal then generated a profitable return, the country from which it originated would receive no benefit. Host country residents, not being able to realize any of the commercial value of biodiversity, have thus been little interested in conservation.

This situation has begun to change a bit, thanks largely to improvements in technologies that have made large-scale screening and cataloging of species economically attractive. Costa Rica has struck several deals with drug companies as well as with several U.S. foundations and universities to develop a “forest prospecting industry.” The long-run goal is to train a Costa Rican workforce capable of regulating biological prospectors. Costa Rica will then grant access to its forests, conditional on receiving a share of profits from any agricultural or pharmaceutical innovations. Building a strong institutional base for this industry is important so that Costa Rica can prevent illegal prospecting, as well as forestall efforts by corporations to synthesize a new drug based on a botanical finding, and then fail to report it.

Essentially what Costa Rica is doing is shifting an open-access, common property resource into a state-owned resource by beefing up its technical enforcement capabilities. This in turn greatly strengthens the incentive for profit-based conservation. Costa Rica is well placed to do this on its own, because it has a relatively efficient bureaucracy, has a highly literate population, already has an extensive national park network, and has strong links with U.S.-based conservation groups.7

Global efforts to protect biodiversity have taken the form of a treaty signed at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The initiative had three central features. First, nations were required to inventory and monitor their biological assets. Second, conservation efforts centered around sustained-yield resource development were to be pursued, conditional on financial support from wealthy countries. Finally, the treaty specified that a product developed from the genetic resources of a country remained the intellectual property of the host nation, unless a company had agreed to a profit-sharing mechanism in advance.8 In other words, under the treaty, a country such as Mexico would have a legal right to block the sale of hybrid corn seeds developed from Mexican maize unless it was guaranteed a share of the profits.

At the Rio Summit, developing nations also tried to get the rich countries to agree to commit 0.7 percent of their annual GDP to sustainable development projects, up from 0.4 percent (from $55 billion to $98 billion annually). However, no such firm commitment was forthcoming. Ultimately, the agreement was signed by 158 nations, and there was one significant holdout: the United States. The United States had several objections, but primary was the provision that assigned host countries the property rights to genetic resources.

Under the agreement, these rights must be purchased by foreign and domestic firms. As we noted in Chapter 20, whenever common property resources are privatized, those who previously had free access will lose out. In this case, multinational seed and pharmaceutical companies, many of them U.S.-based, were the losers. A U.S. biotech industry spokesperson put it this way: “It seems to us highway robbery that a Third World country should have the right to a protected invention simply because it supplied a bug, or a plant or animal in the first place. It’s been weighted in favor of developing nations.” While Japan and Britain shared some of the U.S. reservations, these two nations ultimately signed on under pressure from domestic environmental groups. However, the U.S. Senate still has refused to ratify.9

The Rio agreement is important from a symbolic viewpoint in that the rich countries formally acknowledged the need for a transfer of resources in order to protect biodiversity. However, the treaty has done little to slow down the massive acceleration in species extinction we are currently witnessing.

First, the treaty itself contains no requirement that rich countries contribute to the conservation fund. While significant monies were committed at Rio, no ongoing financial mechanism was established. Second, while the Rio treaty formally assigned to each country the property rights to its genetic resources, no legally binding benefit sharing process has been set up, and the United States has opted out. What if biotech companies ignore or circumvent the international law? Without the kind of technical enforcement capability that Costa Rica is building up, the property rights provision of the treaty is liable to be fairly hollow.

The prospects for strengthening the Rio biodiversity treaty are not good, for two related reasons. First, it is very hard to assess compliance with and progress toward an agreement whose goal is to “protect biodiversity.” As the treaty acknowledges, the problem of species extinction is a diverse and deeply rooted one, ultimately driven by rapid population growth and desperate poverty in poor countries. In short, effectively preserving biodiversity means achieving sustainable development throughout the less-developed world. As related to biodiversity, this will require a substantial increase in the transfer of technology and other resources from wealthy countries to poor ones.

The second obstacle to an effective international agreement is closely related. The loss of biodiversity is unlikely to galvanize the massive aid efforts from the developed world essential to such an effort. The daily extinctions of dozens of species of plants, insects, and animals in the tropical rain forest may deprive our children of important medicines and agricultural products. However, this threat is a negative and distant one. The loss of biodiversity may reduce well-being, but it does not immediately threaten many human lives. By contrast, action to ban CFCs in the ozone case was forthcoming because of the potential for direct and positive harm: massive increases in skin cancer.

To sum up, the framework laid at Rio for protecting biodiversity was certainly helpful, but success on the scale of the Montreal Protocol has not been duplicated. As a result, nongovernmental conservation organizations, some multinational drug and agricultural companies, and host country governments are struggling to protect biodiversity largely on their own. As the next section discusses, however, protecting tropical forests might be an important side benefit of a global warming agreement.

21.4 Stopping Global Warming: Theory

What do the ozone and biodiversity cases tell us about the potential for an international agreement on climate change? The prospects to control global warming fall midway between the examples of the Montreal Protocol and Rio biodiversity treaty. Similarly to ozone depletion, and unlike the loss of biodiversity, global warming represents a distinct, positive threat to a wide range of nations. In addition, similarly to ozone depletion, the greenhouse threat arises from several well-defined atmospheric pollutants—primarily carbon dioxide () and methane. Thus, a treaty can be structured around the concrete goal of controlling these pollutants, instead of an ill-defined target of “preserving ecosystems.” These two features—the prospect of positive harm to our children and the existence of a well-defined problem—improve the prospects for an effective agreement.

However, a global warming treaty shares many of the problems faced in the biodiversity case. Foremost among these is the vastly decentralized nature of the problem. Unlike the case of CFCs, there are millions of producers of carbon dioxide and methane. Virtually no sector of a modern economy operates without producing , and methane pollution arises from sources as diverse as natural gas pipelines, rice paddies, and cattle ranches. The problem seems a bit less daunting when it is reduced to its two main contributors—coal-fired power plants and gasoline-powered transport. Nevertheless, before clean energy alternatives to these technologies (discussed in Chapter 18) become fully cost-competitive, enforcement looms as a major obstacle to an effective treaty.

In addition, as in the loss of biodiversity, both deforestation and economic growth in developing countries have become a major driver of climate change. Around 2010, low- and middle-income countries displaced rich countries as the primary source of annual global warming emissions. China is now number one, followed by the United States at number two. It remains true, however, that since is a stock pollutant, most of the warming we are now experiencing is driven by the historical emissions from the developed world. Nevertheless, with emissions from developing countries now in the lead, this means that “solving” global warming is also tied up with the momentous task of achieving sustainable development in the less-developed world.

What does it mean to solve global warming? Under a business-as-usual scenario, by 2100, concentrations of heat-trapping will climb well above double their preindustrial levels, to 700, 800, or even 1,000 ppm. This will lead to a likely increase in global temperatures of 8–11 degrees F, with far-reaching, mostly negative consequences for human well-being and for the survival of many of the earth’s creatures.

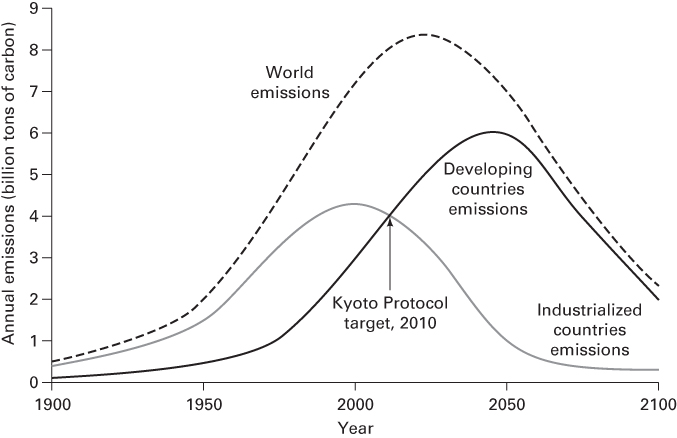

Figure 21.1 outlines a different future. Here, concerted efforts to reduce emissions—beginning globally about 10 years ago—would eventually lead to a stabilization of concentrations in the atmosphere of 450 ppm by mid-century. This would not stop the warming—with at this level, planetary temperatures would still rise by 4 degrees F. But, by freezing the thickness of the carbon blanket (and, post 2050, beginning to roll it back down to 300 ppm), we can buy insurance against truly catastrophic impacts of climate change: rapid sea-level rise from the collapse of the Greenland or West Antarctic Ice Sheets, large-scale methane releases from the tundra, or the fire-driven deforestation of the Amazon and other great forests of the planet.

FIGURE 21.1 Stabilizing Concentrations at 450 ppm

Source: Bernow et al. (1999). © 1999 WWF (panda.org). Some rights reserved.

The figure shows the developed countries meeting the Kyoto targets (roughly 5 percent below levels in 1990 by 2010) and then, by the end of the century, cutting emissions of greenhouse gases by 90 percent. In this scenario, in the short term, poor countries keep on increasing pollution; but by 2050, they too have to make steep cutbacks, getting 50 percent below where they are currently. Figure 21.1 also shows clearly that developing countries from the South will soon far outstrip emissions coming from the industrialized North.

As a reference point and reality check, recall that the European countries have met the Kyoto targets, but U.S. emissions in 2014 were 8 percent above the levels in 1990. Going forward, the Europeans have committed to the mid-term trajectory shown in Figure 21.1, with 20 percent cuts below the levels in 1990 by 2020, but recent U.S. proposals–even if achieved– would only move our country to around the levels in 1990 by 2020. Globally, we are about 10 years behind the schedule shown in Figure 21.1, and so to hit the 450 target would require deeper cuts before 2050 than are shown here, both from developed and developing countries.

Achieving the emission reductions as shown in Figure 21.1—on the order of 90 percent over the next 100 years in the rich countries—may seem to be an impossible task. It is helpful to recall, however that the major pollution source from the transportation sector 100 years ago was horse poop. And we have definitely managed to reduce horse poop in our streets by well over 90 percent. The diagram simply reflects an assumed phaseout of fossil fuels and a transition to a cheap, clean energy future with electricity provided by wind, solar, and biomass and transportation powered by electric and hybrid vehicles, biofuels, and hydrogen fuel cells. These are not pipe-dream technologies. The uncertain questions, however, are how quickly can their costs drop to competitive levels, and how rapidly can these technologies be transferred to the Global South, where emissions are growing the fastest?

It is apparent that, unlike the Montreal Protocol, an effective treaty to slow down global warming cannot focus primarily on regulatory control of industries (and consumers) in the rich countries. Instead, it must eventually confront a broad range of interrelated and difficult development issues: poverty, growth in both population and affluence, and deforestation, while quickly rewiring the planet with clean-energy technologies. Fortunately, the ultimate task still remains the narrow and quantifiable one of reducing carbon and methane emissions.

With this background, the bare bones of a successful treaty must do three things: (1) mandate numerical emission reduction targets for and methane, (2) provide a mechanism by which rich countries effectively transfer technology and resources to poor countries to finance sustainable development, and (3) provide strong enforcement mechanisms. Also recall that the central challenge to an effective treaty is overcoming the free-rider problem—the fact that one country can benefit from an agreement by others to cut global warming pollution, without having to participate in the agreement and pay the costs.

As we will see in the next section, countries have been trying to negotiate a climate treaty since 1992, but with limited success. The original model inspiring the negotiations was the Montreal Protocol: a binding treaty including all countries in which the developed countries go first, and the developing countries follow. However, this approach foundered, significantly because of the free-rider problem. A Montreal-like treaty that did get signed in 1998—the Kyoto Protocol—was ignored by everyone except the Europeans, and there was no mechanism to enforce compliance.

Is there a different model? Economist William Nordhaus (of the Nordhaus-Stern climate change debate from Chapter 1) has argued that the best approach for international climate agreements will take the form of what he calls a Climate Club. A climate club would start as a “coalition-of-the-willing”—countries with the strongest desire to cut global warming pollution. The members of such a club would agree among themselves on national targets and timetables needed, for example, to achieve a 4 degree F warming goal. They would also establish mechanisms to support low-income countries in the club to achieve their goals, through technology transfer and investment, particularly in forest protection.

The key to success for the Club would be that club members would impose a climate club tariff on the imported goods of nonmembers. This tariff would then provide an incentive for nonmembers to join the club and to meet the emission reduction goals required of them. Nordhaus suggests that a general import duty of around 5%—a modest amount—would be sufficient to persuade most countries to join the club and take action toward an intermediate climate goal of around 5 degrees F.10

The very attractive feature of the Club is that it can start small, with the most committed countries, and then grow as the tariffs incentivize other members to join. A key challenge is that the proposed climate club tariffs would be illegal under existing World Trade Organization law, and so an exemption allowing the tariffs would need to be negotiated.11

Nordhaus argues that within the treaty itself, the best set of policies to achieve the national targets would be harmonized carbon taxes—set, for example, at $50 per ton. Having a transparent carbon price would support the monitoring of each nation’s commitment. And of course, global warming pollution taxes would generate revenues that could be used, at least in part, to facilitate investment by richer countries in developing-country emission reductions, creating an additional incentive for participation in the Club.

Nordhaus’s Climate Club idea is new to the climate policy debate, just introduced in the last couple of years. Yet, it is an innovative approach to addressing the fundamental economic challenge facing an international climate agreement: free riding. Interestingly, as we will see in the next section, climate agreements between small groups of countries—perhaps the precursor to a climate club—have also begun to emerge in recent years. We now turn to exploring the brief history and current status of international agreements to attack climate change.

21.5 Stopping Global Warming: Reality

International efforts to tackle global warming date back to the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992. There, the nations of the earth signed the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), negotiated by President Bush senior, and ratified on a bipartisan basis in the U.S. Senate. The UNFCCC set up an ongoing process of annual review, the Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings, to assess progress toward stabilizing the climate. In Rio, countries made only a nonbinding commitment to “try” to stabilize carbon emissions at 1990 levels by 2000. This effort failed—emissions in the United States, for example, rose about 11 percent over the period.

The governments of the world reconvened at COP 5 in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997, and signed a stronger agreement calling for a total reduction in greenhouse gases to 5 percent below 1990 levels by about 2010. The Kyoto Protocol imposed emission targets and timetables on only the industrialized countries. The rationale here was twofold: First, greenhouse gases are long-lived, so although low-income countries would soon catch up in terms of annual emissions, the cumulative emissions from developed countries would remain primarily responsible for climate change over the medium term. Second, poor countries did not have the resources to invest in the alternative technologies—electric and biofueled vehicles and solar and wind-powered electricity—that are needed to address the global warming problem.

Thus, the idea behind the Kyoto agreement—explicitly modeled on the Montreal Protocol—was that rich countries would go first and develop low-cost alternatives to gasoline-powered automobiles and coal-fired power plants. These technologies would then spread from the North to the South, allowing developing countries to leapfrog the fossil fuel–based development patterns followed by the rich countries.

Chapter 16 discussed the trading system set up under Kyoto, including the Clean Development Mechanism, in which rich countries gain credit for clean investments in poor countries. This is one prototype for the kind of large-scale technology transfer that will be needed to stabilize the climate. Also, as noted in Chapter 16, Kyoto currently does incorporate a more limited marketable permit approach: the Joint Implementation procedure, which allows for trade in carbon rights between the industrialized countries that are subject to emission limits.

The Kyoto Accord was ratified by the European countries and by Canada, Japan, Australia, and Russia, but not by the United States. Ultimately, however, only the Europeans took the treaty seriously, setting up the European Trading System discussed in Chapter 16 and meeting their Kyoto targets. All other countries ignored their commitments. The collapse of the Kyoto Protocol globally illustrates in large measure the critical free-riding problem discussed. Opposition to Kyoto emerged, in particular, when conservative governments took power after the treaty was signed in fossil-fuel-rich, high-emission countries: the United States, Canada, and Australia. These countries all have actors likely to lose big from a global warming treaty, including major oil and coal companies, who have substantial political influence.

In December 2009, nations met again in Copenhagen to begin to hammer out a post-Kyoto international framework. No “grand deal” emerged; instead, major nations, including the United States, Europe, Japan, and China, all adopted a UN target of a 2 degree C warming, maximum, above preindustrial levels. As the world has already warmed 1 degree C, that means holding the planet to an additional 1 degree C heating (2 degrees F). This would need to be achieved through a 450ppm emissions strategy as the one modeled in Figure 21.1.

Copenhagen marked two transitions. First, the “rich-nations-go-first” emphasis seen in Kyoto began to fade, as China in particular showed more interest in stepping up to cut emissions. Second, the Copenhagen meeting was seen as the last chance for a “top-down” Kyoto-style treaty, mandating targets and timetables. Failure of this strategy in Copenhagen has since led to the emergence of a new approach of “bottom-up” voluntary commitments made by individual nations.

The most recent major climate meeting was held in Paris in 2015: COP 21. The Paris Agreement was a breakthrough. For the first time, almost all the nations of the earth agreed to a plan to cut emissions. It was a relatively weak plan, comprised of voluntary commitments offered by each country, with no enforcement mechanism. But it was a global plan nevertheless. The United States, for example, agreed to 30 percent reductions below 2006 levels by 2030 (see Chapter 16 on the plan to get there). China agreed to stabilize coal consumption by 2020 and begin to cut emissions in 2030. India committed to reducing the rate of global warming pollution relative to GDP by 33 percent by 2030 from 2005 levels and to boost its energy production from renewable sources to 40 percent by 2030.

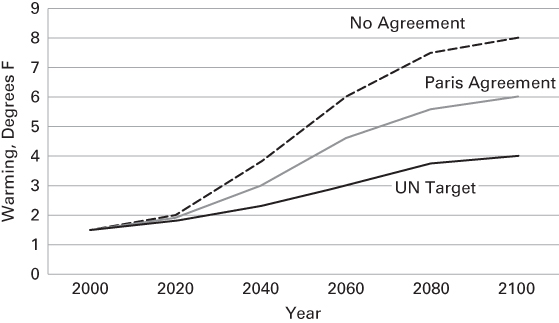

Figure 21.2 shows that prior to Paris, the world was on course for a warming of approximately 8 degree F above preindustrial levels. If the Paris commitments are in fact all met, then we are more likely to stabilize at 6 degrees F. But we still have far to go to achieve the Copenhagen goal of stabilizing at 4 degrees F. As a strategy to get there, the Paris agreement requires participants to return in 2020 with a new round of proposed cuts to get closer to the 4-degree F goal.

FIGURE 21.2 The Impact of the Paris Agreement

Source: Romm (2015).

Note: Warming is above pre-industrial levels, at 1.5 degrees in 2000.

The most surprising development post-Copenhagen and in the run-up to Paris has been Chinese openness to pursuing domestic restraints. Terrible air pollution has emerged as a major political issue in China. Combined with the long-term danger to China’s coastal populations and agricultural productivity, this has led the Chinese government to announce a number of policy experiments—including promotion of electric vehicles, the shuttering of old coal plants (even while new ones are opening), and both taxes and trading systems. Whether such policies will be strong enough to alter the vast momentum of China’s growing carbon footprint will be critical in determining the trajectory of global warming in this century and beyond. The second big question is, how quickly India, the other major low-income polluter, will and can follow China toward a low-carbon energy future? Finally, the election of Donald Trump means that the US may actually withdraw from the Paris deal, or at the least, seems likely to ignore our commitment through 2020. Perhaps continued action by US states to cut emissions will assure the rest of the world that the US will stay committed to the Paris agreement over the long run.

As a final note, the Paris deal was preceded by a bilateral agreement between the two biggest global warming polluters, China and the United States. The deal essentially locked in the commitments the countries would later make in Paris. Perhaps this kind of international agreement happening outside of the UN process, between small groups of countries, will lead to the emergence of Climate Clubs along the lines we discussed in the previous section. Until then, the next step in the UNFCCC process will be the COP 26 meetings in 2020: keep your eyes open to see if the United States, China, and India in particular will show up with commitments to cut global warming pollution strengthened since the Paris agreement in 2015.

Earlier we saw that one of the factors favoring a global warming treaty is that climate change is liable to inflict positive and significant harm on the citizens of many nations. As an example of a clear and present danger yielding an impressive international response, we can look to the appearance of the ozone hole in 1985, which spurred nations into signing the Montreal Protocol. In the global warming case, no individual extreme weather event can be attributed to human-induced climate change. However, 2016 was the hottest year ever, breaking the record set by 2015, which in turn broke the record set in 2014. Along with a hotter planet are coming intensified droughts heat waves, floods, extreme weather events, rising seas, agricultural failures, an increasingly acidified ocean, and the spread of pests and diseases. Ultimately, these cumulative impacts may provide the impetus to an effective global warming treaty.

21.6 Summary

This chapter identifies a basic obstacle to effective international action on global environmental problems: the public good nature of an agreement. Free riding means that agreements are likely to be too weak from an efficiency perspective and to be susceptible to noncompliance. International bodies set up to administer agreements may monitor compliance but have few enforcement powers. One informal tool is community pressure. Formal enforcement mechanisms must be written into a treaty and include restricted access to a compensation fund and targeted trade sanctions.

The Montreal Protocol to protect the ozone layer represents the most successful environmental treaty to date. In a period of 16 years, nations moved from skepticism about the need to regulate CFCs at all to banning the bulk of production. The treaty’s success can be traced to three factors: (1) the rapidly mounting evidence of a significant health threat; (2) the centralized nature of CFC production, which minimized enforcement problems; and (3) the speedy development of low-cost CFC substitutes.

By contrast, the Rio biodiversity agreement has value primarily as a symbol of concern. The treaty formally recognizes two key points: (1) rich nations must finance sustained-yield resource development projects in poor countries if biodiversity is to be preserved and (2) an important obstacle to profit-based conservation has been open access by multinational firms to genetic resources. However, the treaty is weak on enforcement mechanisms, and rich countries have not provided the financing to support sustained-yield conservation measures at the scale envisioned by the agreement. In addition, the failure by the United States to ratify the biodiversity treaty leaves a major player on the sidelines, whose companies do not need to abide by the rules.

On the climate front, the prospects for international agreement are strengthened by the fact that climate change increasingly poses a clear and present danger for many nations and by the fact that the pollutants to be regulated come primarily from one sector: fossil fuels. The challenge, of course, is that fossil fuels currently power the global economy. Without very rapid reductions in the cost, and the widespread diffusion of renewable and clean vehicle technologies, low- and middle-income countries are likely to rely on coal, oil, and gas and so increase emissions as they develop. In addition, deforestation is a major source of global warming pollution, so solving the climate problem, as with protecting biodiversity, is more broadly tied up with meeting the challenge of sustainable development.

The first 20 years of climate negotiations, beginning in 1992, ultimately foundered on the public goods problem. A strong treaty was hard to negotiate, and even when one emerged in the form of the Kyoto Protocol, it was unenforced and largely ignored. However, with China and India showing an increased willingness to come to the table, the Paris Agreement in 2015 finally led to a truly global, if voluntary, deal to cut global warming pollution.

The Paris commitments, if met, would get us halfway to the UN goal of no more than a 4 degree F warming above preindustrial levels. As of this writing, it is unclear whether the Trump administration will formally pull the US out of the Paris agreement, or perhaps just ignore US commitments. The real test for Paris will be whether the rest of the world will stay on board with the US either actively hostile to the treaty or else just out of the picture, and then, whether, absent the US, countries can still come together in 2020 to offer deeper emission reductions toward the 2 degree goal.

Outside of the UN process, over the coming years, international agreements among a small group of countries to make deep cuts in global warming emissions might help overcome the public goods problem. If Climate Clubs do emerge and can also impose import tariffs on nonmembers, this could provide the incentives needed to get truly global cooperation for climate stabilization.

This book has ended, as it began, with a discussion of global warming. Today, we all compounded this problem by actions as simple as driving to work and turning on our computers. Yet, global warming is just one of the pressing environmental problems we will face in the coming years. From the siting of waste facilities at the community level to regulatory policy at the national level to sustainable development around the globe, environmental challenges abound. While these problems are formidable, we have no option but to face them squarely. This book has provided some tools for doing so.

At the risk of repeating ourselves (again!), let us summarize the three-step approach that we have developed:

- Step 1. Set your environmental goal. Efficiency, safety, or sustainability?

- Step 2. Recognize the constraints on effective governmental action. Imperfect information, political influence, and inadequate enforcement.

- Step 3. Look for ways to do better. Incentive-based regulation and clean technology promotion.

Now, get to work.

KEY IDEAS IN EACH SECTION

- 21.0 This chapter discusses the economics of global pollution-control agreements.

- 21.1 Each country has a true willingness to pay for a pollution-control agreement that is a function of both its income and the environmental benefits it is likely to receive. However, because agreements are public goods, the free-rider problem means that they will be both too weak from an efficiency (and safety) point of view and provide incentives for cheating.

- 21.2 Monitoring compliance is typically the responsibility of an intergovernmental organization (IGO) set up by each treaty. IGOs can also issue nonbinding standards and monitor compliance. The three main enforcement tools are social pressure, restricted access to compensation funds, and targeted trade sanctions.

- 21.3 This section describes two agreements. First, the Montreal Protocol initiated a global phaseout of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to protect the earth’s ozone layer. The treaty succeeded due to (1) the clear and present danger from the ozone hole, (2) a narrowly defined problem, and (3) ease of enforcement due to limited number of producers. Second, the Rio Convention on Biodiversity seeks to protect biodiversity (important for existence value and as a gene pool) by encouraging member nations to inventory reserves, take conservation measures, and provide host countries with a share in pharmaceutical and agricultural breeding profits. The treaty has little more than symbolic value due to (1) a clear but distant danger of negative harm, (2) a broadly defined problem, and (3) inability to take action without funding from rich countries.

- 21.4 What factors affect the prospects for an effective global warming treaty? Pros include the likelihood of positive harm and the existence of well-defined problems. Cons arise from highly decentralized producers and the fact that a greenhouse treaty would have to confront sustainability issues ranging from deforestation to population growth. An effective treaty would have three components: (1) numerical emission reduction targets, (2) technology and resource transfers, and (3) good enforcement. One way to overcome the challenge of free riding would be the formation of Climate Clubs that would impose climate club tariffs on imported goods and services from nonmembers.

- 21.5 The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was negotiated in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 and called for voluntary efforts to prevent growth in emissions, which failed. Subsequent meetings led to the signing of the Kyoto Protocol, which, although signed by many nations, was not enforced outside of Europe. Since Kyoto, the international process led to the adoption of a UN target of a 2 degree C warming above preindustrial levels. And in the Paris Agreement, in 2015, for the first time, all countries agreed to concrete steps to cut global warming pollution. If implemented, the Paris commitments would stabilize the planet at 3 degrees C, still above the target. So, the nations also agreed to return with deeper planned cuts at a follow-up to Paris in 2020. The election of Donald Trump as President, who vowed opposition to the Paris accord, likely will preclude U.S. action in support of the agreement, and may weaken the overall response of other countries.

REFERENCES

- Bailey, Martin. 1982. Risks, costs and benefits of fluorocarbon regulation. American Economic Review 72(2): 247–50.

- Bernow, Stephen, Karlynn Cory, William Dougherty, Max Duckworth, Sivan Kartha, and Michael Ruth. 1999. America’s global warming solutions. Washington, DC: World Wildlife Fund.

- Hathaway, Oona. 1992. Whither biodiversity? The global debate over biological variety continues. Harvard International Review 15(2): 58–60.

- Heppes, John B., and Eric J. McFadden. 1987. The convention on trade in endangered species: The prospects for preserving our biological heritage. Boston University International Law Journal 5(2): 229–46.

- Leycegui, Beatriz and Imanol Ramírez (2015) Identifying a WTO exception to incorporate climate clubs, Biores 9-7, 18 September. Online http://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/biores/news/identifying-a-wto-exception-to-incorporate-climate-clubs

- Nordhaus, W. D. 2001. Global warming economics. Science 294: 1283–4.

- Nordhaus, William (2015) “Climate Clubs to Overcome Free-Riding” Issues in Science and Technology, XXXI, 4, Summer. http://issues.org/31-4/climate-clubs-to-overcome-free-riding/

- Ozone Secretariat (2016) Montreal Protocol—Achievements to Date and Challenges Ahead (UNEP) Online at http://ozone.unep.org/en/focus/montreal-protocol-achievements-date-and-challenges-ahead

- Romm, Joe (2015) In Historic Paris Climate Deal, World Unanimously Agrees To Not Burn Most Fossil Fuels, Climate Progress, December 12. Online http://thinkprogress.org/climate/2015/12/12/3731236/paris-deal-fossil-fuels/

- Rosendal, G. K. 2011. Biodiversity protection in international negotiations: Cooperation and conflict in beyond resource wars scarcity, environmental degradation, and international cooperation, ed. Shlomi Dinar. MIT Press: Cambridge.

- Sedjo, Roger A. 1992. Property rights, genetic resources and biotechnological change. Journal of Law and Economics 35(1): 199–213.

- Somerset, Margaret. 1989. An attempt to stop the sky from falling: The Montreal Protocol to protect against atmospheric ozone reduction. Syracuse Journal of International Law and Commerce 15(39): 391–429.

- Zhao, Jimin. 2005. Implementing international environmental treaties in developing countries: China’s compliance with the Montreal Protocol. Global Environmental Policy 5(1): 58–81.