CHAPTER 20

Environmental Policy in Low-Income Countries

20.0 Introduction

At the end of Chapter 19, we discussed the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that provide a framework for assessing progress toward a just, ecologically sound, and prosperous future. The intertwined social and environmental goals range from investing in education, to achieving food security, to protecting forests and biodiversity, to empowering women, to cutting down global warming pollution. This chapter moves on to consider a variety of actions that low- and middle-income countries can take to work toward the SDGs.

As in our discussion of environmental policy in the United States, we need to be fully aware of the constraints that government policymakers in poor countries face. The potential for government failure in poor countries is high. Indeed, one of the SDGs is titled “Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions” and focuses specifically on the need to strengthen governance, respect for human rights, and the rule of law in all countries. Given these concerns about government failure, the first half of this chapter analyzes the measures designed to harness the profit motive in pursuit of sustainable development. First, poor-country governments should eliminate environmentally destructive subsidy policies. Second, by strengthening property rights and systems of justice, governments can reinforce community and private sector motives for conservation.

While government can do a lot by selectively disengaging itself from market transactions and improving private incentives for conservation, government ultimately must be counted on to take an effective, proactive role in promoting sustainable development. This chapter thus goes on to examine the role that regulatory and clean technology strategies must play.

Finally, we end with a trio of related topics: resource conservation, debt relief, and international trade. In each case, resource rents that should form the foundation for economic development are not being captured by poor countries. The basic message of the chapter is that achieving the SDGs requires investment; without effective capture and investment of resource rents, sustainable development is not possible.

20.1 The Political Economy of Sustainable Development

Before jumping into specifics, we need to pause to consider the constraints under which government policy operates. Part II of this book focused considerable attention on the obstacles to effective government action in the United States, raised by both imperfect information and the opportunity for political influence.

The United States is a wealthy country with a fairly efficient marketplace and government. By contrast, the average person in a less-developed country is a very poor person, and this poverty undermines the efficiency of both markets and governments. Per-capita annual income in low-income countries is about $600 or about $1.75 per person per day. But, even these abysmal figures disguise the true extent of poverty, as there is considerable wealth inequality within countries.

In general, most countries have a small political-economic elite who control a disproportionate share of national income and wield disproportionate influence over political events. This kind of tremendous economic and political disparity often has a historical basis in the period of colonial rule. For example, throughout Latin America, the current, dramatic concentration of land ownership in the hands of a small percentage of the population can be traced to the hacienda system established by the Spanish colonists. Or, consider another example: Britain granted Zambia independence in 1964 after exploiting that nation’s rich copper deposits for 40 of its 70 years of colonial rule. Upon independence, only 100 Africans out of a population of 3.5 million had received a college education, and fewer than 1,000 were high school graduates.1

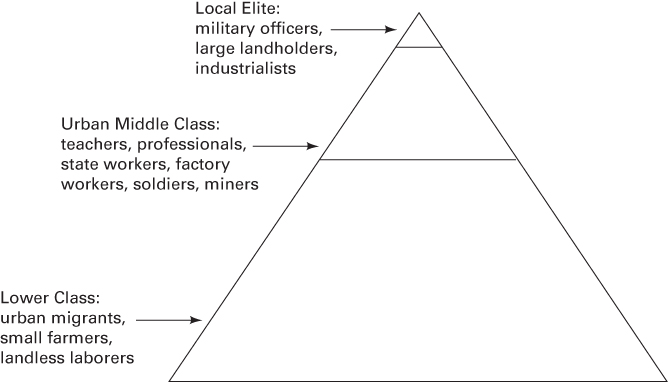

At the risk of grossly oversimplifying, the typical class structure in a developing country can be represented by the pyramid shown in Figure 20.1. At the top are a small group of wealthy landholders, industrialists, and military officers, often educated in Western universities. Businessmen in this group include both local capitalists and local managers of multinational corporations. Below them come the urban middle class: teachers, professionals, state employees, factory workers, miners, and soldiers. The vast majority of the population are the poor: urban migrants, under-employed and often living in substandard housing or shantytowns, rural small farmers, and landless laborers.

FIGURE 20.1 Class Structure in Poor Countries (generalized)

Sustainable development—increasing net national welfare (NNW) for the average individual—by definition requires focusing on the lower class, as they are the average individuals. Moreover, it is this group who, out of brute necessity, often run down the local stock of natural capital in an unsustainable manner. As we begin to evaluate development and environmental policy in poor countries, the question we thus need to ask is, “Does the policy improve or exacerbate the position of the poor?”

Unfortunately, because the lower class generally has little political power in developing countries, this question is seldom central to policy design. Elite-dominated governments, often maintaining their power through military force, rarely provide democratic avenues for those adversely affected by government policy to register their protests. Yet, for environmental progress, the ability to protest is vital.

As argued in Chapter 12, the primary environmental lesson from the Communist experience is that a lack of democracy stifles the recognition of environmental problems. In the absence of substantial pressure from those affected, government will have neither the power nor the inclination to force economic decision-makers—whether state bureaucrats, managers of private corporations, or ordinary citizens—to recognize and internalize the external environmental costs generated by their actions.

In addition to nonrecognition of important problems, when government leaders are not democratically accountable, opportunities for corruption multiply. This is especially true when even top government officials in poor countries fail to achieve a standard of living common to the middle class in Western countries. Not surprisingly, given their very low pay and level of training, corruption among low-level bureaucrats in poor countries is not uncommon. Thus, as a general rule, government bureaucracies in poor countries are not particularly efficient. (The few developing countries for which this is not true tend to be economically quite successful.) As a result, even when development and/or environmental problems are in fact recognized, and policies are set up to attack them, progress may be quite slow.

Partly in response to government failures in poor countries, the so-called nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have emerged to deal with the issues of rural development, small farmers’ rights, urban service provision, and natural resource protection. NGOs include international development and human rights groups, the international arms of environmental and conservation groups, local environmental groups, peasant and rural workers’ unions, and urban activist groups.

Unlike in wealthy countries, the “environmental movement” is very small in poor countries. Thus, progress toward sustainable development must spring from either environmental concern on the part of ruling elites or a nonenvironmental interest on their part in population control, food security, technological innovation, or resource conservation. No strong groundswell drives the political process in a sustainable direction.

To summarize, for a variety of reasons including colonial history, small political-economic elite, undemocratic governmental structures, and poorly trained and paid bureaucrats, factors leading to government failure are compounded in poor countries. Given this potential, policies that depend on sophisticated analytical capabilities or aggressive monitoring and enforcement are not likely to succeed in many parts of the developing world.

Weak governments and the lack of popular environmental counterpressure mean that business interests have a much freer hand in affecting the environmental policy in poor countries. Both domestic and multinational businesses operate in the developing world. Domestic firms are owned and operated by the residents of the poor country; multinational firms operate in many countries around the globe and are typically headquartered in a developed country. Multinationals have a dominant presence in most extractive and resource-processing industries, as well as sectors such as chemicals and paper.

The influence of business, whether domestic or multinational, on environmental policy goals can be positive. For example, businesses can create jobs leading to balanced growth and a subsequent reduction in population growth rates. Or, they can import or develop a new clean technology. However, the influence can also be negative. Businesspeople may bribe officials to obtain subsidized access to timber or other resources and may understate profits to avoid taxation. Or, businesses might promote subsidized credit programs, allowing them to import capital-intensive agricultural technologies that displace farmworkers—on net, leading to an increase in unemployment and poverty. Or, business might use its resources to discourage the passage and/or enforcement of environmental or resource-protection legislation.

The point here is neither to condemn nor praise business as an agent of environmental change in poor countries. Rather, the point is simply to remind that business managers, whether multinational or domestic, are generally not interested in sustainable development. They are interested in profit. To the extent that profit opportunities promote sustainable development, business will do so as well. However, businesses will just as eagerly pursue profit-driven options that are ultimately unsustainable.

Similarly, the point is not to condemn governments in poor countries as hopelessly corrupt or inefficient. There are many examples of government success as well as failure in the developing world. Ultimately, we must rely on poor-country governments to undertake greater effective action if we seek to achieve a sustainable future. There is simply no other choice.

20.2 Ending Environmentally Damaging Subsidies

Both rich and poor countries around the world maintain a broad array of subsidies for particular industries with the purported intent of promoting economic development. Some of the forms these subsidies take include special tax breaks, privileged access to imported parts and materials, protection from international competition, low-cost access to natural resources, the provision of subsidized or interest-free loans, and investment in infrastructure.

Unfortunately, many of these subsidy policies have had the effect of undermining the progress toward the SDGs. This section looks closely at the forest industry, where government policy has often worked to promote a rapid and unsustainable exhaustion of the resource. To begin with, governments often sell public timber to logging companies at prices that are “too low.” By this, we mean that governments fail to capture all the resource rent associated with the timber. As discussed in Chapter 9, for timber harvesting to be sustainable, all of the resource rent must be retained in the host country and invested in created capital.

In the recent past, the governments of Ghana, Indonesia, and the Philippines have received less than 38 percent of the total rents from timber production in the form of sales revenue and taxes.2 By failing to capture all the rents, governments make logging artificially profitable, and this speeds up the depletion of the resource. In addition, once timber sales have been consummated and roads built, it has proven very difficult for governments to enforce environmental contract terms in remote areas or to monitor illegal cutting and smuggling of timber.

Many governments also engage in infrastructure development to support forestry—building roads and ports and surveying and grading timber. In the extreme, taxpayers actually pay firms to harvest timber. This has occurred in the United States, where the Forest Service sometimes sells timber at prices that do not cover its administrative and road-building expenses. This direct subsidy from the Forest Service has been as high as $230 million per year. Comparable problems exist in the developing world.

Poor countries have also subsidized “downstream” industries, which process raw timber into lumber and other finished wood and paper products. Subsidies include substantial tax breaks and subsidized credit, as well as placing bans on the export of unfinished logs. Many of these policies have not succeeded, however, due to high tariffs in rich countries designed to protect their wood-processing industries. Moreover, due to a lack of domestic competition, wood-processing industries in poor countries tend to be inefficient and require continuous subsidies. In addition, their existence puts further pressure on the government to artificially lower the timber prices to maintain employment.

Governments have also sponsored colonization projects to resettle landless farmers in rainforest areas. Such conversion efforts have been judged a success in peninsular Malaysia, where large portions of the country’s forest have been converted to permanent tree crops such as rubber and palm oil. However, efforts in Brazil and Indonesia have failed, and the land is sometimes abandoned after deforestation. In part, this failure has resulted from poor soil quality. In addition, the policies have been hampered by inadequate, though still substantial, government efforts to develop distribution and marketing channels for small farmers in remote areas. Subsidies for these programs, from the government and the World Bank, ranged as high as $10,000 per household in Indonesia, where GNP per capita is $560.3

Finally, governments have been quite active in promoting the spread of cattle ranching in forested areas. This process has advanced furthest in the Brazilian Amazon, where cattle ranching has been a primary driver of deforestation. Under the theory that ranching would serve as a spur to the general economic development of the Amazon, and concerned about securing its national borders through settlement, the Brazilian government pumped more than a billion dollars into beef industry subsidies.

To summarize, with the ostensible goal of supporting resource-based economic development (and influenced by factors as diverse as national defense and personal gain), policymakers in poor countries have established an array of subsidies for logging companies, forest product industries, small farmers, and large ranchers. With a few exceptions, such policies have failed to generate stand-alone industries and have continually drained capital from other sectors. With limited economic progress, population growth has not declined. Because of the policy emphasis on ranching instead of basic foodstuffs, and the failure of small farm programs to take root, food security has not improved. And little clean technology has been developed or introduced.

At the same time, subsidy policies have led to unsustainable declines in natural capital—the forest resource. In addition, they have caused environmental damage, ranging from siltation and flooding to forest fires to a tremendous loss of biodiversity. Finally, native inhabitants of the forests have lost access to their means of subsistence, and their cultural survival is threatened.

This section has explored in detail some of the subsidy policies that promote rapid deforestation around the world, for little, if any, net economic benefit to poor countries. Subsidies for other products that aggravate environmental damage include pesticides, fertilizers, irrigation water, and especially energy. In 2015, total energy subsidies worldwide were a staggering $3.5 trillion–including in developing countries such as China, India, Iran, and Indonesia. In many countries, electricity and gasoline are sold at prices well below cost, incentivizing their overuse, and generating higher urban air pollution and global warming emissions. Moreover, countries must make up the difference by taxing other products or reducing spending elsewhere in the economy.4

Environmentally damaging subsidies are not unique to poor countries, as our discussions of the U.S. Forest Service and of energy and agricultural subsidies in Chapters 17 and 18 make clear. And just as subsidy elimination is difficult in rich countries, so it will be in poor countries. Subsidies can seldom be eliminated without some form of compensation for the losers.

On political and sometimes equity grounds, removing environmentally damaging subsidies requires resources to compensate people who lose out. Nevertheless, eliminating such subsidies often presents a cheap way to improve environmental quality in poor countries. Removing subsidies requires no ongoing governmental expense, and sustainability can be enhanced through the productive use of the resources freed up.

20.3 Establishing and Enforcing Property Rights

Earlier in Chapter 3, we identified one of the primary causes of pollution and resource degradation—open access to common property. Recall that the open-access problem arose when individuals considered only the private benefit and costs from exploiting a shared resource—air, land, or water—without considering the external social costs imposed on others. Recall also that traditional societies managed common property problems through informal social controls and moral sanctions.

However, as traditional control mechanisms have broken down, and both population and consumption pressures have risen, the free-access problem has emerged as a major underlying source of environmental degradation worldwide. When the property rights or titles to resources such as land or fisheries are not clearly defined or are poorly enforced, the people who exploit the resource have little incentive to engage in profit-based conservation or invest in long-lived environmental protection measures such as erosion control. To improve this situation, government has three options.

COMMUNAL OWNERSHIP

Where an existing community is managing the property sustainably, government policy can protect and enforce the existing communal property right. Often, this will mean restricting access to outsiders and may require imposing limitations on the use of sophisticated technology. For example, in one case, cooperative fishing agreements in southern Brazil broke down when nylon fishing nets were adopted by some members of the group, giving them an “unfair” advantage. In addition, under Brazilian law, the group could not exclude outsiders, who also used such nets. The primary advantage of communal ownership patterns, when they can be supported by cohesive communities, is that they tend to be quite sustainable.5

One of the most successful modern experiments in communal ownership rights was Zimbabwe’s CAMPFIRE (Communal Areas Management Programme for Indigenous Resources), which reached its heyday in the mid-1990s. Rural district councils, on behalf of the communities on communal land, were given the right to market access to wildlife in their district to safari operators. The district councils would then make payments to the communities. CAMPFIRE was successful in promoting both community development and conservation, for villages saw their elephant herds and other game species as resources to be protected rather than as agricultural nuisances to be eliminated.

From 1989 to 2001, CAMPFIRE produced some $20 million of revenue for the participating communities, 89 percent of which was generated by sport hunting. Sadly, the CAMPFIRE program lost effectiveness as a result of political turmoil in Zimbabwe,6 CAMPFIRE is an example of community ownership that relies on payment for ecosystem services or PES. For more on this notion, see Section 20.6.

STATE OWNERSHIP

Government can declare the land a national forest, reserve, or park, or it can regulate an ocean fishery. However, a simple declaration is inadequate. Government must also devote the necessary resources to protecting the boundaries of the reserve in order to prevent unauthorized uses. This kind of enforcement task can be extremely difficult for most poor countries. Even in a country with a relatively efficient bureaucracy such as Costa Rica, illegal deforestation on state-owned reserves continues to be a major problem.

Economists often compare Zimbabwe’s successful CAMPFIRE experience for maintaining elephant herds against Kenya’s less successful National Park Strategy. The Kenyans designate refuges, with access controlled by the central government, and attempt to rely on a police force to prevent poaching. Compared to CAMPFIRE, this strategy is expensive, creates resentment among the populace, and provides no incentive for local people to protect wildlife. However, the recent collapse of Zimbabwean government is a telling reminder that no strategy for conservation can succeed in the presence of a failed or failing state.

PRIVATE OWNERSHIP

The final option to overcome the common property problem is to assign property rights to private individuals. However, this process is also more difficult than it seems on the surface. First, it is not free, as government resources must be put to work, delineating and enforcing private property rights. Moreover, privatizing forested land can also have ambiguous environmental impacts. For example, as a way to clearly establish ownership uses, many poor countries require that settlers clear the land in order to take the title (as was the practice on the U.S. frontier). This process, of course, encourages deforestation. Yet, without actual occupation and use of the land, settlers and government officials would have a difficult time validating whose claim to a piece of land is legitimate. Even where clearance is not required, establishing legal title to land in many poor countries can take years. As a result, farmers tend to clear the land anyway in order to establish de facto control.

Yet, because they risk losing their land, farmers who have not attained legal title tend to underinvest in profit-based conservation measures such as erosion control, as well as investments that increase farm output. To encourage such measures, governments can speed up the titling process, for example, by employing more surveyors and land clerks and by providing better law enforcement to prevent illegal evictions. This will increase the security of farmers’ private property rights and should encourage them to invest more in their land. Privatization is most useful for promoting sustainable development when it serves as a safeguard against the taking of small farmers’ land by the politically powerful.

Privatizing commonly held property often hurts those who previously had access under traditional law. For example, privatization of rural land in Kenya led to married sons and wives losing their traditional land rights, because they were not represented in the process. And in many instances, privatization schemes provide an advantage to wealthy and/or educated individuals to increase their wealth at the expense of the poor.7 This type of privatization is counterproductive from a sustainability point of view as it tends to increase poverty and downgrade women’s social status, thus increasing population growth rates while reducing food security. Privatization efforts designed to boost profit-based conservation must therefore be conducted carefully so as to increase rather than decrease both the social status of women and general employment opportunities.

To summarize, clarifying and strengthening property rights is a way to directly reduce environmental damage by “internalizing externalities.” When property rights are clearly defined, then the owner—a community, the government, or an individual—bears a larger part of the social costs of environmental resource degradation or depletion. Individual and community ownership schemes have an advantage in this respect over government ownership, because people at the local level are directly affected by resource degradation. As a result, they have a greater incentive than do government managers to maintain the productivity of the piece of the environment they “own.”

Ownership at the individual or community level thus tends to promote profit-based conservation, while conservation under state ownership depends on the strength of environmental concern within the governing elite. As we have argued previously, such concern may be quite weak, and even where it is strong, the enforcement capabilities of poor-country governments can make resource conservation and environmental protection difficult.

The first two sections of this chapter have focused on ways that poor-country governments can improve environmental quality: either by selectively reducing environmentally damaging subsidies or by strengthening communal and private property rights in order to promote profit-based conservation. We now move on to a consideration of more proactive government policy: regulation and clean technology promotion.

20.4 Regulatory Approaches

Environmental regulation is a new phenomenon in the developed world. Most of the major laws were passed within the last 45 years. Regulation is even more recent in developing countries: Mexico, for example, passed its comprehensive federal environmental law in 1988. In this section, we argue that a mix of direct regulation and indirect pollution taxes will generally be most effective in a developing country context.

Chapters 15 and 16 have already provided an in-depth look at the theory of regulation. It was argued there that, in general, an incentive-based system (pollution taxes or marketable permits) is both more cost-effective in the short run and better at encouraging technological advancement in the long run, than a so-called command-and-control approach to pollution control. Recall that a stereotypical command-and-control system features (1) uniform emission standards for all sources and (2) the installation of government-mandated pollution-control technologies. The inflexibility in the approach means that cost-saving opportunities that can be captured by incentive-based systems are not exploited and that incentives for improved technology are limited. This lesson holds for poor countries as well, with a couple of caveats.

First, monitoring and enforcement are the weakest link in the regulatory process in rich countries. This observation holds even stronger in poor countries. Mexico, for example, has been trying to beef up its enforcement efforts, partly in response to the North American Free Trade Agreement, discussed later in this chapter. Yet, despite some highly publicized efforts, including plant shutdowns, enforcement remains quite weak by U.S. standards. Thus, the primary focus of regulatory policy in the developing world must be enforceability.

Pollution taxes can improve enforcement, because government benefits materially from enforcing the law. This is especially true if the enforcement agency is allowed to keep some portion of the fines. Command-and-control systems also have some enforceability advantages, when regulators can force firms to install low-marginal-cost (“automatic”) pollution-control technologies. However, recall that even such automatic technologies, such as catalytic converters or power plant scrubbers, break down and require maintenance.

The second rule that poor-country governments must heed in selecting regulatory instruments is to seek administrative simplicity. For example, the city of Dalian in China has a comprehensive regulatory strategy to deal with severe problems of water, air, and chemical pollution. Dalian government officials have shut down old, inefficient, and highly polluting plants; mandated the relocation of some plants from central city areas to the suburbs, with new pollution-control requirements; and imposed command-and-control upgrades on others. While a pollution tax or tradable permit system might have been considered, pollution problems in the city were not subtle, and relatively straightforward command-and-control strategies have achieved substantial improvements in local air and water quality. On the other hand, China is considering regional cap-and-trade systems for carbon dioxide, which poses no immediate health threat, but rather long-term negative impacts from climate change.8

In practice, avoiding administrative complexity and ensuring enforceability means that pure incentive-based systems (pollution taxes or marketable permit systems) may not be feasible. However, in conjunction with command-and-control systems, the use of indirect pollution taxes is often a good approach. In contrast to direct pollution taxes, which directly tax the emission of pollutants, indirect pollution taxes impose fees on inputs to, or outputs from, a polluting process. Examples include energy or fuel taxes (discussed in Chapter 18) or taxes on timber production.

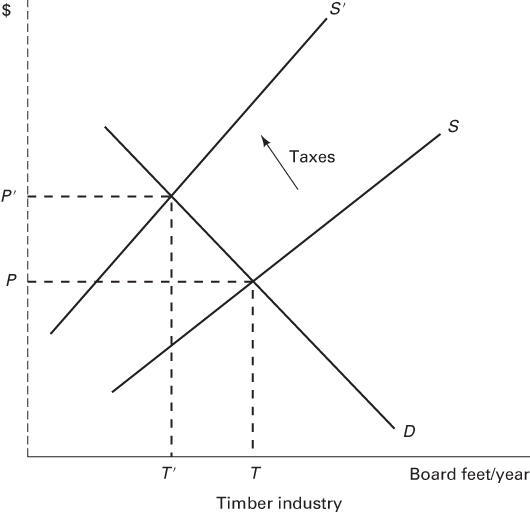

The example of taxes on timber sold to mills (called royalties) is an interesting one, as it illustrates some of the problems raised by indirect taxation of pollution. The idea is that taxing rainforest timber production will make logging less profitable, thus leading to a reduction in this activity. This in turn may be desirable because logging contributes to environmental damage ranging from siltation and flooding to loss of biodiversity to an aggravation of global warming. The situation is illustrated in Figure 20.2.

FIGURE 20.2 Increased Royalties and Logging Activity

In a classic supply-and-demand analysis, increased royalties raise costs to firms, causing some to drop out of the market. This shifts the supply curve up to , and the timber brought to market drops to . This appears to be the desired result of the policy. However, an offsetting effect may in fact lead to a much smaller reduction in the actual area logged. As royalties are raised, fewer tree species become profitable to harvest. Yet, to get the remaining profitable species, firms may still need to clear-cut the same acreage. Firms then remove the profitable species, leaving much of the timber that would formerly have been brought to market behind; this process is called high grading. Thus, although increased royalties will have a big effect on the timber brought to market, they may have a smaller impact on the acreage logged.

To solve this problem, one might suggest a more direct pollution tax—a royalty based on the acreage logged. Such a tax would get at the problem in an up-front way. But, monitoring the logging activity is much difficult than slapping a tax on logs as they come to the mill, so the indirect tax wins out on enforceability grounds. Another alternative would be to vary the royalties by species and impose higher taxes on high-value trees, as is done in the Malaysian state of Sarawak. This reduces high grading and thus can have a bigger impact on acreage reduction.9 In summary, the lesson from the timber royalty case is that indirect pollution taxes are not direct pollution taxes, and their ultimate effect on pollution or resource degradation cannot be taken for granted. The impact of indirect taxes on the environmental problem at hand must be carefully considered.

This is not to say, however, that indirect pollution taxes are a bad idea. Well-designed indirect taxes can substantially affect environmental problems. In addition to such measures, cost-saving flexibility can be built into command-and-control regulatory structures wherever possible. To see how the use of an indirect tax combined with flexibility in a command-and-control regulatory approach can reduce the costs of pollution control, we turn to the case of air pollution control in Mexico City.

Mexico City is home to over 21 million people. Air pollution there was once among the worst in the world. During the winter of 1991, the pollution problem was at an all-time high: athletes were warned not to train outside, birds dropped dead out of the trees, and vendors began selling oxygen on the street. The government began taking steps to control the problem, including the shutdown of some major private and public-owned industrial facilities and incentive-based measures such as increased parking fees in the central city. By the late 2000s, Mexico City had become a global success story, achieving air-quality levels comparable to Los Angeles. However, recent relaxations of air-quality rules have led to backsliding on air quality, with the re-emergence of severe smog alerts in 2016.10

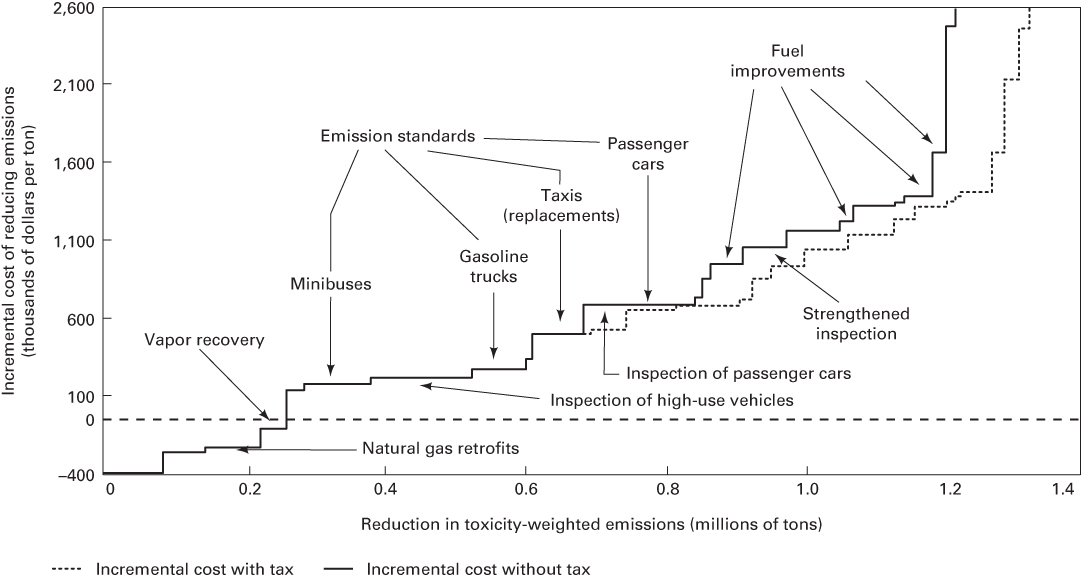

When the problem was at its height, a World Bank study constructed a marginal cost of reduction curve for air pollution from motor vehicles in the city; this curve is reproduced in Figure 20.3. The curve starts out at the left with measures that actually save money: retrofitting some high-use public vehicles to natural gas and recovering refueling vapors. However, the options for further improvement—first emission standards, then strengthened inspection, and then improvements in fuel—become increasingly costly. The author estimated that by using these command-and-control measures alone, pollution could be reduced by 1.2 million tons per year, at a cost of about $1,800 per ton for the last unit removed.

FIGURE 20.3 Air Pollution Control in Mexico City, Marginal Costs from Vehicles

Source: From WORLD DEVELOPMENT REPORT 1992 by World Bank. Copyright 1992 by The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc.

However, as indicated by the dotted line, if the measures were coupled with a relatively low gasoline tax (of about $0.05 per liter), the same pollution reduction could be achieved at lower cost. As you can see in the graph, there are estimated marginal savings of about $300 per ton of air pollution for the last ton reduced. The reason: the gas tax would reduce overall driving and forestall the need for more expensive command-and-control measures to achieve a given reduction in pollution. In fact, the government has since raised gasoline taxes by a substantially higher margin than that the study recommended.

However, because a gasoline tax is not a direct emission tax, it is not fully cost-effective. For example, both dirty and clean cars are taxed at the same rate. The equal marginal cost of reduction principle necessary for cost-effectiveness (Chapter 15) is thus not satisfied. As a result, the World Bank study recommended that cleaner cars receive a rebate of some of their gas tax when they are inspected, thus encouraging their purchase. In another move toward cost-effectiveness, the Mexican government required taxi drivers to buy new, cleaner vehicles every 3 years. This measure generated a large environmental bang for the buck because taxis are driven 10 times as far per year as are private cars.

The government also pursued one symbolic but highly cost-ineffective regulatory policy: the Day Without a Car program. Under this program, travel by car, depending on the license plate number, is banned on a specified workday. This brief description provides a good opportunity to present a

This section has argued that for reasons of enforceability and ease of administration, poor countries will most often rely on command-and-control regulatory methods, combined with indirect pollution taxes. Often, the two measures can complement one another. In addition, careful analysis often reveals fairly simple ways to increase the cost-effectiveness of both indirect pollution taxes and command-and-control regulatory systems. Examples from Mexico City include gas tax rebates for clean cars at inspection time and tight regulation of highly polluting sources such as taxicabs.

20.5 Sustainable Technology: Development and Transfer

In addition to regulation, promoting the adoption of more sustainable technology is the other proactive tool that poor-country governments have to improve environmental quality. Chapters 17 and 18 provide a general discussion of clean technology. There we defined a clean technology as the one capable of delivering comparable services at comparable long-run private costs to existing technology and doing so in an environmentally superior manner. In poor countries, we need to tack on another condition. In the interests of controlling population growth by reducing poverty, technologies that the government promotes should also (1) not reduce employment and/or (2) improve the economic position of the poor, especially women. The so-called sustainable technologies are clean technologies that also help reduce poverty.11

This section addresses three questions about promoting sustainable technology. First, how can sustainable technologies be identified? Second, how are they developed? Third, what steps can be taken to promote their diffusion?

Technologies can be judged sustainable only after field testing and may be sustainable only under certain conditions. For example, one study examined the introduction of irrigation pumps and a new type of rice into a drought-stricken region of northern Mali. The new technology increased yields dramatically and increased employment. Overall food security thus rose. The increased yields also made it possible for the communities to afford the imported capital necessary for production, at least in principle. (Outside support from the United Nations had not yet been withdrawn.) However, the greater centralization of production fostered by the pumps concentrated the economic power in the hands of the males of a wealthier ethnic group, thus increasing both gender and income inequality.12

Is this technology sustainable? At this point, it is difficult to tell. Over time, one would need to answer the following two questions. First, in the absence of outside aid, can the villagers afford to operate and maintain their more capital-intensive production method? In other words, is the technology really profitable and thus self-sustaining? Second, do the income and food security benefits of higher yields outweigh the increase in inequality? In other words, are women and the ethnic minority group on balance better off after the introduction of a new technology? If the answer to both of these questions is yes, then we would judge the technology sustainable.

Sustainable technologies need not be sophisticated. Examples include erosion control methods such as building rock or clay dikes or planting trees and efficient cooking stoves, which reduce charcoal use by several hundred percent. These technologies can dramatically improve environmental quality while boosting the material well-being of people in poor countries. The short-term cost-effectiveness of these technologies is essential. Poor people cannot afford to adopt new techniques unless their advantages are clear-cut and substantial.

How are sustainable technologies developed? Chapter 19 stressed that rich countries must bear much of the cost of research and development of technically sophisticated clean technologies—photovoltaic cells are a good example. However, external aid is often needed to establish and promote simple sustainable technologies as well. An NGO called Plan International financed a project in the African country of Burkina Faso, which serves as a good example. The NGO found that reintroducing traditional erosion control techniques, using mostly locally crafted implements, boosted yields of peanuts and grains by over 100 percent. Later, outside agronomical assistance was gradually withdrawn, and the project became self-sustaining. Unfortunately, this success story was not widely replicated. The Burkina Faso government, while being supportive of the project, simply had no money to invest in it.13

While potentially beneficial technologies often have to be developed with assistance from the rich countries, the actual users of the technology must be closely involved in the design process. This is true first because poor-country residents, particularly farmers, often have the greatest knowledge of potential solutions to a given problem. Second, if the technologies do not suit the needs of the users, they will never be adopted, no matter how “sustainable” they are in theory.

Poor-country governments, sometimes in combination with international development agencies and NGOs, can employ a wide range of tools to promote sustainable technologies—from design standards for technology to technical assistance programs to consumer and producer subsidies to research and development grants. The advantages and disadvantages of these options, summarized in Table 20.1, were discussed in detail in Chapter 17 and are not further reviewed here.

TABLE 20.1 Policies for Sustainable Technology

| Policy | Late-Stage Sustainable Technologies |

| Design standards | Energy and water efficiency |

| Technical assistance | Waste reduction in manufacturing, alternative and agroforestry, passive solar, wind power, energy and water efficiency |

| Small grants/loans/tax credits | Energy and water efficiency, active solar, passive solar, agriculture and agroforestry, wind power |

| Policy | Early-Stage Sustainable Technologies |

| R&D | Agriculture and agroforestry |

| Infrastructure investment | Mass transit, agriculture and agroforestry, active solar, wind power, telecommunications |

While government’s efforts to promote technologies are important, the private sector and multinational corporations in particular will typically play an important role in diffusing new techniques of production and consumption. Sometimes, these technologies are sustainable, sometimes not. One beneficial influence of direct foreign investment by multinational corporations in manufacturing is that they may bring with them cleaner production technologies. For example, multinational investment has promoted the diffusion of relatively clean technology in the paper and pulp industries.14 In addition, international product quality standards such as ISO and sustainable supply chain initiatives by companies such as Nike have affected labor and environmental practices in developing countries.

On average, multinationals, with higher profits, higher visibility, and easier access to technology, probably have somewhat better environmental and safety records than do domestic firms in poor countries. Nevertheless, and not surprisingly, multinational operations in the developing world are generally dirtier and more dangerous than are their similar facilities in rich countries.

The most tragic example of this so-called double standard was illustrated in the wake of a 1984 chemical explosion in Bhopal, India, at a plant owned by a subsidiary of Union Carbide. More than 2,000 people were killed and up to 200,000 injured, many severely, by a toxic gas cloud. While the Bhopal plant was technologically similar to a sister plant in West Virginia, safety systems in Bhopal were very poorly maintained.15

More generally, manufacturing and agricultural production methods imported from rich countries by multinationals tend to be fairly capital-intensive. A chemical plant in Mexico is very much similar to a chemical plant in Ohio. If taxes on these firms are low and/or their profits are not reinvested locally, the use of this capital-intensive technology may lead to little net increase in employment or reduction in poverty, while at the same time aggravating the environmental problems. This is yet another example of the critical need to capture and invest domestically the economic surplus from foreign investment.

This section has defined a sustainable technology as a clean technology, which also helps reduce poverty. The rapid diffusion of such technologies in poor countries is crucial if they hope to outrun a neo-Malthusian cycle in which increased poverty leads to high rates of population growth, thus generating more poverty, and so on. Such technologies must also alleviate poverty in a clean way, because environmental degradation in many poor countries is already quite severe. With both their populations and per-capita consumption of resources likely to increase substantially over the next 50 years, dramatically exacerbating environmental decline, poor countries must leapfrog the path of dirty development followed by their rich neighbors. Sustainable technology may deliver the means to do so.

However, developing, identifying, and diffusing sustainable technologies are expensive tasks that will not be accomplished without a major and ongoing commitment of resources. At the same time, the recipient communities must be full partners in the process. On one of our desks is a beautiful picture of a modern windmill on a hilltop in eastern Zimbabwe, built there by a Danish aid group to electrify a remote village. Unfortunately, the windmill had been inoperative for over a year when we took the picture. The village was unable to raise the money to buy spare parts, which had to be imported from Denmark. The lesson: a successful sustainable technology depends much more on the social needs, capabilities, and organizations of the people it is intended to serve than it does on the provision of hardware.

20.6 Resource Conservation and Debt Relief

Several times in the previous few chapters, we have remarked that it has proved difficult for poor countries to successfully conserve natural resources—forests, wetlands, rangelands, and fisheries—by simply setting aside reserves and parks. Problems are faced both in establishing such protected areas and in managing the regions once they have been created.

Over the last few decades, we have seen fierce battles in the United States over wilderness set-asides to protect the habitat of the spotted owl in the Pacific Northwest, and to prohibit oil development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Similar development–environmental struggles are played out in poor countries, but the stakes there are more dramatic. Failure to develop will mean that many millions of people will continue to face hardships with inadequate food, housing, health care, and other necessities. But, rapid development also threatens to degrade the ecosystems. Many poor countries are rich in biodiversity. Poor countries are located disproportionately in tropical areas that tend to contain many more species than temperate areas do. Both desperately poor people and wealthy development companies desire access to the resources, and together, they can form a potent anticonservation political force.

Even when a protected area has been established, the government faces the daunting task of enforcement to prevent game poaching, illegal logging, and the invasion of landless farmers. These governments often have very limited budgets and simply cannot meet the challenges they face. Given these facts, there has been an increasing recognition that protecting the natural resources in poor countries requires directly addressing the economic needs of the poor people who depend on, and threaten, those resources. This section explores three related policy options for strengthening the link between resource protection and economic opportunity—sustained-yield resource development, payments for ecosystem services (PES), and debt-for-nature swaps.

Sustained-yield resource development means using available renewable natural capital in an ecologically sustainable way. Under a sustained-yield rule, harvests cannot exceed the regenerative capacity of the land or fishery (see Chapter 10). To illustrate this concept, let us consider the economics of deforestation in the Amazon rain forest in Brazil.

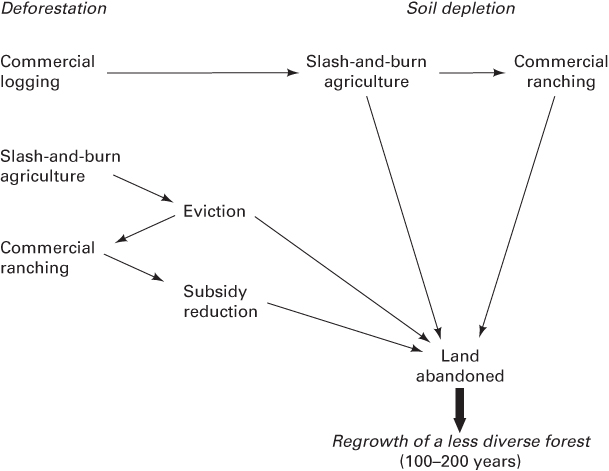

As illustrated in Figure 20.4, three primary forms of commercial resource-based activity exist in the Amazon, and they sometimes occur in sequence. First, the rain forest is clear-cut by logging companies, small farmers, or commercial ranchers. The latter two groups tend to simply burn the fallen timber. Small farmers, sometimes following the roads built by loggers, grow crops for a few years. However, these early migrants often move on, either abandoning their land or selling out to cattle farmers. This technology is known as shifting cultivation or slash-and-burn agriculture.

FIGURE 20.4 The Deforestation Process

When populations and farm plots are small, slash-and-burn agriculture can generate a sustained yield because the rain forest is given time to recover. However, as population pressure has increased, and ranchers have moved in to follow the farmers, the system has in some cases become ecologically untenable.

There is ongoing debate as to the motivation for land abandonment by both small farmers and cattle ranchers. Some argue that the poor-quality tropical soils make rainforest farming unsustainable; others maintain that poor and politically powerless pioneers are unable to hold onto the property that they farm as a second wave of wealthier migrants move in. Finally, in some cases, reductions in subsidies have led to some abandonment by ranchers.16

How could sustained-yield resource development proceed in the Amazon? As we will see, the rain forest does have substantial economic value that might be exploited in an ecologically sustainable manner. Doing so will require applying a successful mix of the policies described previously: eliminating unsustainable subsidies, clarifying property rights, and promoting sustainable technologies via measures such as technical assistance programs, infrastructure development, and subsidized credit programs. The problem is compounded, however, because much of the benefit of sustained-yield development accrues to people outside of the rain forest, particularly to those in rich countries. Getting us to pay “our share” for the public good of rainforest protection becomes an added policy challenge.

What sustained-yield values do the rain forest hold? First, experience has shown that there are profitable, sustained-yield farming and ranching methods, suitable for tropical forest soils, that do not require shifting cultivation. Governments can encourage farmers to adopt these sustainable technologies both by directly promoting them through technical assistance programs and targeted credit subsidies and by eliminating the subsidies for unsustainable practices. Deforestation will be slowed if farmers and ranchers can eliminate their voracious need for more land.

More generally, the standing forest is increasingly viewed as a resource with substantial economic value. From a commercial perspective, the harvesting of wild products such as meat and fish, and primates (for medical research), could generate an annual income of $200 per hectare, more than is earned either by one-time clear cutting or by unsustainable cattle ranching.17 Developing this potential would require nurturing a marketing and transportation infrastructure as well as clarifying property rights within the rain forest. Some kind of communal or private ownership would be necessary to avoid the overharvesting of profitable wild resources such as nuts, meat, or vegetable oils on commonly held property.

The rain forest holds two other important products: medicine and a gene pool for agriculture. Tropical forest species form the basis for pharmaceutical products whose annual sales are of billions of dollars. The forest undoubtedly contains many more valuable species, thousands of which may be lost each year. However, the medical value of the rain forest lies not only in its biodiversity; the native Amazon people have a medical knowledge base that is also being threatened by deforestation. Finally, the huge gene pool represented by the forest is economically important for breeding disease-resistant and high-yield agricultural crops.

In addition to these commercial benefits, the forest yields a variety of other ecosystem services. One of these is carbon sequestration; a substantial portion of the world’s carbon dioxide is tied up in the rainforest biomass. When the forests are burned, the is released into the atmosphere, contributing to global warming. Deforestation contributes an estimated 6–17 percent of total global emissions from human sources.18 In addition, the rain forest serves as a rainfall regulator by recycling much of its own moisture. As deforestation proceeds, the Amazon basin may well dry out as large parts of the forest are burned down and converted to savanna. This would release a huge pulse of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, further warming the planet and affecting the rainfall patterns throughout Brazil.

Finally, many people have expressed considerable moral interest in protecting the rain forest, its natural species, and its human cultures. From an economic point of view, this concern represents an existence value for the rain forest (see Chapter 5). Especially in rich countries, people have expressed a willingness to pay for rainforest preservation independent of the material economic services that the tropical forest might provide.

The benefits from medical, agricultural, environmental, and existence value services provided by the rain forest accrue primarily to those living outside of the Amazon and, indeed, Brazil. Thus, rainforest protection is a classic public good, as described in Chapter 3. Many of us have been solicited by environmental groups to contribute money to the efforts to “save the rain forest.” While each of us has a material stake in such a project, we also have an incentive to free ride on the efforts of others to provide the public good. As a result, economic theory predicts that rainforest protection groups will raise less than the amount of money we as a society are really willing to pay for such efforts.

This in turn means that private sector efforts to promote sustained-yield development in the Amazon will be inefficiently low on a simple benefit–cost basis. Traditionally, economists have argued that government needs to step in and use its power to tax in order to provide an efficient quantity of public goods—whether this involves a national park, clean air, or national defense. In an international context, this implies that to protect the narrow economic interests of their citizens, rich-country governments will have to raise aid money for rainforest protection. Of course, such aid might also be justified on the grounds of economic sustainability and fairness to future generations.

One method of generating funds in rich countries to provide funds for conservation in poor countries is to institute programs of payments for ecosystem services (PES). Around the world, dozens of such efforts have been launched in recent years. An ambitious recent initiative is the UN’s REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) program. REDD is working to provide incentives to forest landholders in developing countries to retain and restore their forests so as to keep the carbon sequestered in the trees and soils. But as most of these programs, REDD is currently underfunded. Because rich countries are often major beneficiaries of resource preservation, an efficient level of conservation will be achieved only if a mechanism is established by which rich-country residents pay for the benefits they receive.

In other cases, low- or middle-income countries themselves have initiated ambitious PES programs. Costa Rica launched a PES program in 1996, Pago por Servicios Ambientales (PSA). PSA pays landowners to maintain forests or plant trees in order to provide four ecosystem services: carbon sequestration, water provision, biodiversity conservation, and scenic beauty. The money to pay landowners comes primarily from a tax on fossil-fuel use with a lesser amount coming from foreign sources. The program has achieved considerable success. Prior to the start of the PSA, Costa Rica had one of the highest rates of deforestation in any country. Since 2000, Costa Rica had net positive reforestation.

Other successful PES programs in low- or middle-income countries have been instituted in South Africa (Working for Water Program), and the largest program of all in China, the Sloping Land Conversion Project (or “Grain for Green Program”). The Grain for Green Program pays farmers to plant trees on steep slopes to prevent erosion, better manage runoff to prevent flooding, sequester carbon, and provide other ecosystem services. The program has led to a large increase in the area of forest in China. More local and regional PES programs involve payments by water users to protect watersheds that provide drinking water. Following the success of such a program in Quito, Ecuador, such “water funds” are now spreading quickly to other cities in Latin America.

Another approach to provide incentives to invest in resource conservation is through a debt-for-nature swap. During the 1970s and early 1980s, many developing countries accumulated a huge quantity of debt owed to private banks in rich countries. Merely paying the interest on this debt remains a huge burden on poor countries today. The debt burden poses a major obstacle to sustainable development, as it reduces investment in the created capital that poor countries desperately need. Under a debt-for-nature swap, a rich-country group (government, NGO, or bank) pays off a portion of the loan, typically at a deep discount. Banks are willing to sell this debt at a paper loss, because they suspect that they will not be repaid in full anyway. In exchange, poor-country governments must agree to invest a certain amount of money into a resource conservation program at home. These programs tend to focus on beefing up enforcement and supporting sustained-yield resource development at existing preserves. The actual ownership of the natural resource does not change hands.

The developing country benefits in several ways. First, the debt is reduced. Second, it can undertake the required conservation measures at home. Finally, the conservation program can be financed using local money, not scarce foreign currency (dollars, yen, or euros). It is thus “cheaper” from the poor country’s perspective. Figure 20.5 provides the details of a swap between the Brazilian government and the U.S.-based NGO, the Nature Conservancy.

- The Nature Conservancy buys $2.2 million in Brazilian debt owed to a private bank. The bank agrees to a price of $850,000 for the debt, $0.38 to the dollar.

- The Nature Conservancy donates the debt to FUNATURA, a Brazilian conservation NGO. FUNATURA, in turn, uses it to buy $2.2 million in long-term Brazilian government bonds, paying 6 percent interest, or $132,000 per year.

- These funds accrue to a partnership between the Nature Conservancy, FUNATARA, and IBAMA (the Brazilian EPA). Their goal is to manage the Grande Sertão Veredas National Park, in the interior highland of the country. Endangered mammals that have taken refuge in the park include the jaguar, the pampas deer, the maned wolf, the giant anteater, and the harpy eagle.

- The management strategy includes purchasing “buffer zone” lands around the park, hiring park rangers, and promoting sustained-yield resource development. Early priorities include such basic measures as the purchase of a motor boat and a four-wheel-drive vehicle, and the construction of a park headquarters.

FIGURE 20.5 A Debt-for-Nature Swap in Brazil

Source: Fundaçao Pró-Natureza and the Nature Conservancy (1991).

Debt-for-nature swaps are one way for residents of rich countries to express their demand for resource preservation in poor countries. However, their use has been fairly limited. Consummated deals have reduced the total debt in poor countries by only about 1 percent of the total Third-World debt. About one-quarter of these swaps have been financed by private parties, primarily conservation NGOs. The rest of the efforts have been paid for by rich-country governments.19

The restricted use of the option reflects, in part, resistance on the part of poor-country governments, who are concerned that environmentalists from rich countries will “lock up” their resource base. Probably, more significant is the fact that NGOs in rich countries have been able to raise only limited funds for such purposes. Due to the free-rider problem, discussed previously, such an outcome is predicted for private groups that seek to provide public goods. At the same time, government efforts have been limited for lack of political support. If debt-for-nature schemes are in fact effective in conserving resources in poor countries—and the record is too recent to fully judge—a significant expansion could well be justified on benefit–cost grounds.

In summary, in poor and densely populated countries, the only feasible way to conserve natural resources is often to link conservation with enhanced economic opportunity. That conservation often provides valuable ecosystem services is one way to motivate funds for conservation. Successful conservation programs bring together willing buyers (those who benefit from provision of ecosystem services) with willing sellers (typically landowners who take actions to enhance provision of services). The success of PES programs in many low- and middle-income countries provides hope that conservation overall can succeed in poor countries that provide important local and globally valuable ecosystem services.

20.7 Trade and the Environment

During the 2016 election, there was one surprising issue on which candidates Trump and Clinton agreed: both were opposed to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. This free-trade deal had been championed by another surprising coalition, including President Obama and Congressional Republicans. Clinton’s opposition in part sprung from concerns that the trade deal would accelerate environmental degradation globally and in the United States, and, along with Trump, she argued that the agreement as written would also undercut workers’ wages in the United States. Twenty-five years ago, similar concerns created headlines during the debate over the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA, a 1993 agreement between Canada, Mexico, and the United States, was designed to reduce tariff and subsidy trade barriers and eliminate restrictions on foreign investment and capital mobility. Passage of NAFTA in the United States was hotly contested, in part because of fears that it would exacerbate environmental decline in all three countries. We now have two decades of history to evaluate these concerns.

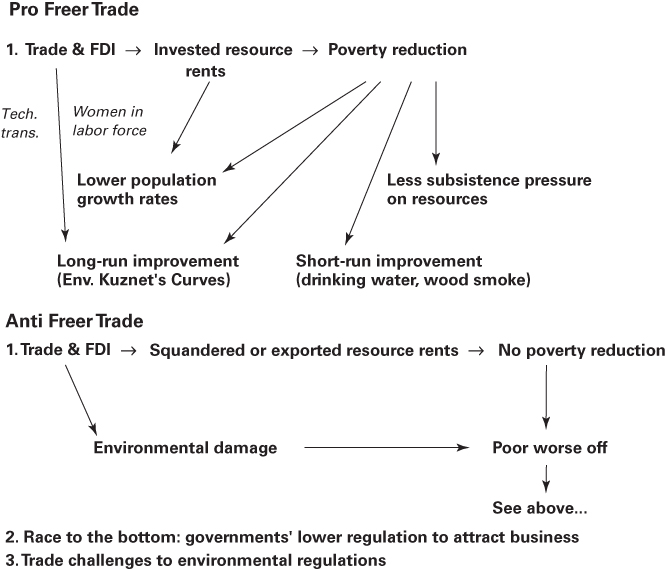

There are essentially three environmental arguments against freer trade, and one environmental argument in favor, all well illustrated by the NAFTA debate and all summarized in Figure 20.6. The argument for the free-trade act was that, by stimulating investment and economic growth in Mexico, poverty would be reduced and cleaner technologies would be imported and adopted, leading to a “flattening” of the Environmental Kuznets Curve. As we learned in Chapter 19, poverty reduction in poor countries can have important environmental benefits as water and air quality improve, pressures on nonrenewable resources decline, more resources are available for investment in health care, education, and family planning, and parents are provided with the option of pursing a quality rather than a quantity strategy for family size. In the case of NAFTA in particular, advocates argued that the agreement process strengthened both democratic and environmental political movements within Mexico.

FIGURE 20.6 Trade and the Environment

Environmental critics of the treaty lodged three principal objections. First, they argued that, in fact, it would not reduce poverty. For example, NAFTA required the Mexican government to significantly reduce subsidies for corn farmers. It was feared that hundreds of thousands of small farmers might lose their livelihoods, as cheap northern grain entered the market. (Canada and the United States have built up tremendously productive farm sectors through their own subsidy policies.) While urban dwellers in Mexico might benefit from lower corn prices, they would also suffer from substantially increased migration to the cities and downward pressure on wages. As a result, it was possible that they too would be worse off. With greater poverty would come higher birth rates and more pressure on local resources.

Following the passage of NAFTA, U.S. grain exports to Mexico grew rapidly, though urban consumers appeared not to benefit substantially from lower prices due to monopoly pricing. And, somewhat surprisingly, Mexican maize production in subsistence areas appears to have stayed relatively constant. U.S. producers grabbed all of the growth in the market, depressing the prices, but rural farmers continued to produce for their own subsistence. The bottom line: U.S., not Mexican, farmers profited from the growing internal market, and U.S. and Mexican wholesalers, not Mexican consumers, appear to have gotten the largest share of the increased surplus.20 Thus, Mexico’s corn farmers have been hit with lower product prices, but they are not low enough to drive the subsistence growers off the land in large numbers.

The second charge against the treaty was that Mexico, with its weak environmental enforcement apparatus, would face dramatic and escalating pollution problems as a result of increased investment in manufacturing and vegetable production. There is evidence, for example, that pesticide pollution would increase in Mexico (but decrease in Florida) following a trade agreement. The following judgment was thus made: environmental improvements that accompany reductions in poverty and the import of technology will not compensate for the direct increase in pollution. On balance, it was argued, freer trade will lead to deteriorating environmental conditions in poor countries. Ironically, at least in the maize case, it appears that the reverse is true: as U.S. corn production increased by close to 1 percent to serve the Mexican market, agricultural pollution shifted from Mexico to the United States.21

Again, the response from supporters of trade was strengthen enforcement activities, don’t restrict trade. NAFTA does contain a “side agreement” on environmental issues that in principle gives parties the ability to prod businesses that “persistently” violate environmental laws to comply. However, the process is complex and restrictive; the commission set up to oversee complaints has accomplished little.22

The final environmental charge against a free-trade agreement is that environmental regulations in rich countries will be weakened as (1) business mobility increases and (2) foreign governments and companies issue trade-based challenges to environmental laws. This process is known as a race to the bottom. In Chapter 6, we learned that differences in the stringency of environmental regulation in fact appear to have little influence on business location decisions. Much more important are wage differences and access to markets. Given this, U.S. lawmakers appear to have little to lose by maintaining strong environmental standards. Indeed, Mexico could begin stringently enforcing its laws without sacrificing investment from the United States.

Unfortunately, it is not always reality but perception that matters in regulatory decisions. Much of the public and many policymakers appear to believe that strong environmental standards discourage investment. Evidence from the few industries in which environmental regulation has discouraged investment can be used as a stick by industry to weaken standards.

Free-trade agreements can also lead to a race to the bottom as they give foreign governments and corporations the ability to challenge certain regulations as trade barriers. Table 20.2 provides a list of several challenges. One of the most widely cited has been a case in which the U.S. government imposed a ban on the import of Latin American tuna. The embargo was enacted because these countries were not using fishing techniques required by U.S. law to reduce the incidental killing of dolphins and other marine animals. Mexico challenged the embargo under the terms of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a predecessor to the WTO. The trade court ruled in Mexico’s favor, arguing that member nations were not allowed to dictate production methods beyond their borders. The United States was forced to rescind the ban or face international trade sanctions.

TABLE 20.2 Trade Challenges to Environmental Regulation

Sources: Based on data from Shrybman (1992); U.S. defeated in its appeal of trade case. 1996. New York Times, 30 May D1; and Wallach and Sforza (1999).

| Measure | Trade Agreement | Challenger | Decision |

| U.S. ban on Latin American tuna imports | GATT | Mexican govt. | Ban declared illegal |

| Danish requirement that drinks be sold in reusable deposit containers | Treaty of Rome | U.K. govt., European beer manufacturers | Deposit requirement upheld, reuse weakened |

| U.S. ban on asbestos | U.S.-Canada FTA | Quebec govt. | Ban overturned on other grounds; trade issue referred to GATT |

| Canadian requirement that fish must be sampled prior to export, to promote conservation | U.S.-Canada FTA | — | Requirement declared illegal |

| Canadian review of natural gas export license | U.S.-Canada FTA | U.S. energy companies | Review dropped |

| U.S. standards for reformulated gasoline | WTO | Venezuelan government | Standards revised |

| Japanese efficiency standards for auto engines | WTO | U.S. govt., auto manufacturers | Case dropped |

| California ban on MBTE | WTO | Methanex Corp. | Review dropped on a technicality |

An unanticipated feature of NAFTA that has raised major concern relates to restrictions not on trade, but rather on investment. A clause in the treaty, known as “Chapter 11,” prohibits countries from expropriating the property of investors without compensation. Under this clause, companies have started to sue governments that impose environmental regulations, arguing that these regulations are in effect expropriations of profit. For example, a Canadian cattle company has sued the U.S. government for $300 million over closing the border to Canada for beef imports following a mad cow incident. A Canadian mining company has sued the United States for $50 million in damages over a California requirement that open-pit mines be backfilled and restored if they pose a threat to Native American sacred sites. And a U.S. company won its suit against Canada over a ban on the gasoline additive MMT. The Canadian government, after losing in the NAFTA tribunal, lifted the ban and paid the company $13 million in damages.23 And in 2016, a Canadian company filed an eye-popping $15 billion claim against the U.S. government for denying a permit for the controversial Keystone Pipeline that would have enabled shipment of Canadian tar sands oil to Houston. As these cases show, Chapter 11 effectively undermines the “polluter pays” principle and gives companies the right to pollute, rather than giving governments the right to prevent pollution.

As Table 20.2 and Chapter 11 examples illustrate, by prohibiting import and export bans, regulations, and tariffs, free-trade agreements can tie the hands of environmental agencies. In effect, environmental decisions made by democratically elected bodies (congresses and parliaments) can be overruled by a very closed international legal process, of which the primary treaty charge is to promote free trade for the sake of efficiency gains.

This section has provided a look at the debate on the environmental impact of free-trade agreements. Clearly, trade can be a vital component of any strategy to promote sustainable development. When trade works to reduce poverty, it can provide environmental benefits in the form of greater investment in air and water quality, reduced pressure on the local environment, and lowered population growth rates.

However, the economic growth that accompanies free-trade agreements need not reduce poverty. In the Mexican case, the “losers” from NAFTA have been the large class of small corn farmers. More generally, we saw in Chapter 19 that trade in natural-resource-based industries can foster unsustainable development. This occurs when the full resource rent is not reinvested in created capital in the developing country. In a world whose poor-country governments are both debt-burdened and have difficulty collecting and productively investing tax revenues from resource-based industries, such an outcome is not unlikely.

Critics have also charged that, despite the environmental benefits that accompany growth, the direct increase in pollution will lead to a decline in environmental quality in poor countries. Finally, they charge that environmental regulations in rich countries will be weakened as business mobility increases and legal challenges are lodged by international competitors.

In response to economics and environmental worries about globalization, there have been many attempts to “localize” economic activity by using the power of government to promote the purchase of, especially, local food. This movement has been spurred on by a belief that shipping the average tomato 1,500 miles from farm to fork simply has to be an inefficient practice! Let’s pause to consider a food

An encouraging experiment promoting local food production comes from Brazil’s fourth-largest city, Belo Horizonte. There, the city government has provided choice retail locations throughout the urban area for farmer’s markets and for “ABC” stores (ABC is the Portuguese acronym for “food at low prices.”) These shops are required to sell 20 basic, healthy foods at state-set prices and then are free to sell other goods at the market rate. The city also serves 12,000 meals a day, made from local foods at low-cost “People’s Restaurants.” The result of these and other initiatives has been the development of a healthy local food industry and dramatic reductions in hunger: Belo Horizonte has cut its infant death rate by more than 50 percent. The cost has been quite reasonable: about $10 million each year, around 2 percent of the city’s budget, and about one penny a day per resident.24

Is free trade good or bad for the environment? Freer trade is generally championed by economists because it tends to increase efficiency; and as we know from Chapter 4, more efficient production means a bigger overall economic pie. The environmental challenge is to channel the efficiency gains from trade into investment in a sustainable future. From this perspective, freer trade should be viewed as a means to an end—stabilizing population growth and building human capital, enhancing food security, transferring sustainable technology, and conserving resources—not as an end in itself. Yet at this point, trade agreements have only just begun to acknowledge environmental and sustainability concerns.

20.8 Summary

Environmental policy in poor countries cannot be narrowly viewed as “controlling pollution.” The complex and conflicting problems of poverty, population growth, and environmental and resource degradation require a broader focus: promoting sustainable development along with several dimensions outlined in the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

This chapter has considered several general steps that governments can take in these directions. These include reducing environmentally damaging subsidies, working to clarify and enforce communal or private property rights, regulating pollution in as cost-effective a manner as possible, promoting the development and transfer of sustainable technology, conserving natural capital by encouraging sustained-yield resource development, and ensuring that the gains from trade are funneled into measures promoting sustainable development.

One recurring theme in this chapter has been the question of who will pay for these programs. Until recently, many poor countries have questioned the wisdom of environmental or natural resource protection, reasoning that they could not afford to engage in such measures. There is an increasing recognition, however, that improving environmental quality is often a good economic investment. The financial reality remains unchanged, however. Developing countries still cannot afford to make many of these investments.

As an example, the people of Burkina Faso would benefit greatly if the erosion control measures discussed in Section 20.5 were widely disseminated, boosting agricultural productivity and incomes and slowing down population growth rates and rural-to-urban migration. Yet, the country is desperately poor. As a result, such programs are proceeding at a snail’s pace, funded through private donations by people in affluent countries.

Ultimately, sustainable development in low-income countries is unlikely to occur without a substantial commitment of resources by those of us in rich countries. This commitment can take a variety of forms: research and development in clean and sustainable technologies ranging from solar and wind power to biotechnology to improved refrigerators and stoves, funding of family planning efforts, debt relief in the form of debt-for-nature swaps, international aid for rural development projects, financial and technical assistance in the implementation of environmental regulatory programs; the removal of trade barriers to poor-country products, and adjustment aid to help poor countries reduce their own environmentally damaging subsidies.

In some instances, this kind of resource commitment is justified on the basis of narrow self-interest. Global pollution problems such as the accelerated greenhouse effect and ozone depletion will not be adequately addressed without such efforts. Natural resources that we in rich countries value—medical products, agricultural gene pools, wild animal species, and wilderness—will be rapidly exhausted if we do not pay our share for their protection. Beyond narrow self-interest, however, resources must be committed by those of us in rich countries if we want to ensure a high quality of life for our children and grandchildren.

One environmental impact of continuing population and consumption growth will be simply to intensify the problems of local air and water pollution, disposal of solid and hazardous waste, exposure to toxic chemicals, and the disappearance of green spaces and wild creatures. On the other hand, such trends are leading to threats to the global environment that were not even on the radar screen 30 years ago—such as climate change and ocean acidification. The final chapter of the book turns to the increasingly critical issue of global environmental regulation.

KEY IDEAS IN EACH SECTION