5

How Do Engineering Projects Get Created?

When we get our first job, we are likely to be assigned to work on an existing engineering project; we are not troubled by the question of how this engineering project came into existence. Who created it? Why? How is it being paid for? How did it come to pass that it is our company that is doing the work? But as we progress in our careers, we come to realize that these aspects matter a lot. In fact, understanding them, so that you can help your company win new projects, is an important path for you to achieve attractive assignments and career success. In this chapter, I will therefore teach you the basics about winning engineering projects for your company, which centers around something called the “proposal.”

5.1 Engineering Projects are Created in Response to a Need, or a Vision

Somewhere out there in the world is a group of users who need something; let us imagine a scenario wherein they decide that they can best obtain it by buying it from someone outside of their own organization, rather than making it themselves. Let's say that what they need is a loaf of bread.

First of all, they need to talk among themselves, and reach agreement on exactly what is it that they want to buy. White or whole wheat? Non‐GMO flour? Gluten free? Sliced? What kind of packaging? As you can see, even to buy a simple loaf of bread, there are a set of decisions to be made.

Probably, they will decide at some point to commit the decisions that result from those discussions to writing; there is no point in getting it wrong later due to poor memory. If I go to buy a coffee for my wife, you can be sure that I write down “a small decaf peppermint mocha with extra whipped cream.” What if I came home with a latte instead? She would not be happy.

If we write down simple things like the above (or a grocery shopping list), you can be sure that when someone plans to pay money for a complex engineered system, they will also try to write down something about what they want to buy. They will write down not only the characteristics of the item they wish to buy, but perhaps other things too: what is the date by which they need it, what kind of payment terms are they offering (e.g. payment upon placing an order versus payment upon delivery, or some other arrangement), and so forth. We call such a document a request for proposal.

Engineered systems tend to be more expensive than a loaf of bread. When you buy a car, you probably shop around; even after you have decided on a make, model, accessory package, and color, you may still visit a few dealers and see who has the best price, or the quickest delivery.

Buyers of engineered systems shop around too. The way they do this is to send their written request for proposal to a set of companies that they believe might be able to build what they want (or these days, post their request for proposal onto an on‐line forum where vendors know to look), and ask them to make an offer – in writing – about what they could provide, when they could provide it, how much it would cost, what kind of warranty they would offer, and many other relevant factors. We call such a written offer a proposal.

Companies can then look at the request for proposal, decide if they wish to respond (or not – it costs money to write a proposal; we call this decision a bid / no‐bid decision), and if they decide to respond, they create a written proposal that they send back to the buyer. The buyer has likely specified a date by which such proposals are due.

The buyer will then read all of the proposals (and might invite some or all of the proposers to make an in‐person presentation), and eventually will select the provider that appeals to them, based on whatever selection factors the buyer deems important: price, schedule, capability, reputation, warranty, other factors, or some combination of all of these. The buyer then negotiates additional details with the selected vendor, which allows the two parties to agree on some type of formal purchase agreement; this might be a purchase order, a contract, or some other form of written agreement.

For the typical complex engineered system, this formal purchase agreement will take the form of a legally binding contract.

And then the selected vendor is ready to start the engineering project, to build the item that the buyer wanted, in accordance with the terms of their proposal and that formal purchase agreement.

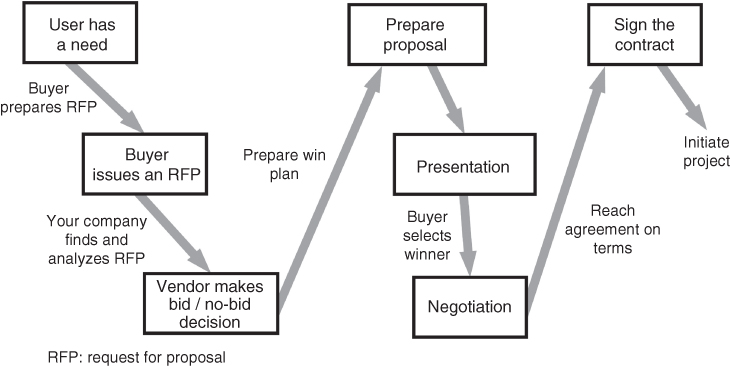

This sequence of events is depicted in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 The steps leading to the commencement of an engineering project.

The vendor in general will not (and ought not) to start working on the project until the formal purchase agreement (of whatever type) is executed by both parties. Otherwise, they may get stuck with unreimbursed costs if the buyer ends up selecting some other vendor, changes their mind and decides not to buy anything at all at this time, changes their mind about what they want to buy or when they want to receive it, or any other material factor that would be defined in rigorous terms in the executed purchase agreement.

Let's define the term proposal in a little more detail. A proposal is a written formal offer to perform a specified piece of work, under specified conditions, to create a specified set of deliverables (products, services, and data), on a specified schedule, for a specified price, under a specified set of payment terms and timing, and under a specified set of contract terms (e.g. how to resolve disputes, etc.).

Since the proposal, as an offer to the buying organization, usually legally commits the offering organization to the terms specified in the proposal, the proposal must be signed by someone who is authorized to commit the offering organization (e.g. an officer of the corporation).

Once the buying organization has read your company's proposal, they may choose to accept your proposal, that is, tell you in writing that they wish to engage your company to do the work described in their request for proposal and your proposal. Alternatively, they may choose to reject your proposal, which is their way of saying “we have decided not to engage your firm for this piece of work.”

Receiving written notice from the buying organization that they have chosen to accept your proposal is good news, but you still ought not to start work until the purchase order or contract is actually negotiated and signed by both parties.

Proposals are often prepared in the context of a competition, that is, someone who wants to buy a product or service will ask more than one company to prepare a written proposal, stating in advance that they will only be signing a contract with one of the bidders (the winner).

The buying organization then selects the winner and notifies the other bidders that they were not the winner.

On occasion, the buying organization might already know that they want your company to do the work, and therefore they do not plan to have a competition. Perhaps you built a related product for that buying organization already, and they were happy with your work. Running a competition takes time and money, and the buying organization may decide that running one for this particular product is not to their advantage, since they have confidence that your organization is the supplier they want.

We use the term sole source for such a situation, that is, the buying organization will solicit a proposal only from a sole organization. Notice that they will still ask for a proposal; in this case, not as a basis for a competitive selection process, but instead to make sure that there is agreement between them and you about what is to be done, how it will be done, when it will be done, how much it will cost, and so forth. Even for sole‐source contracting, it is still necessary and appropriate to get all of the terms and conditions agreed to in writing before work starts … and the proposal is a big part of that task.

Why do we care about proposals? Why am I giving it an entire chapter in this book? Remember, in Chapter 1, we discussed the fact that virtually 100% of company revenue comes from projects. And nearly every one of those projects (whether internally funded or externally funded) comes from a proposal. Proposals are what bring revenue – in the form of projects – to companies. Writing winning proposals is the only way to generate revenue, pay the bills, pay employees, and keep the company in business.

And if you are the buyer, proposals are what allow you to select the right team and organization to build your product or service. Whether you are buying or selling, proposals are essential.

Let's describe the process for externally funded and internally funded projects in more detail.

In many businesses (e.g. aerospace, construction and building contracting, public works, architecture, and many others), virtually 100% of company revenue comes from competitive contract awards (or, on occasion, sole‐source contracts that follow successfully completed competitive contracts). Every single one of those awards is the result of a proposal in response to an externally sponsored competition.

In other types of businesses (e.g. those that build for the marketplace – like car companies and computer companies), there is an internal competition to decide what products or services to build and offer. Those too are usually resolved via proposals, albeit sometimes less formal than externally sponsored proposals.

Here is an example of how it works in such internal competitions. Let's say that you are the chairman of Apple. Your executive team probably has dozens of ideas (proposals, in various degrees of formality and completeness) about what the company should invest in and bring to market next. You, as chairman, will in essence run an internal competition (the degree of formality will vary) to decide which are the products and services in which you will invest as the “next thing.”

As you can see, whether your company lives off external competitions or internal competitions, proposals are the mechanism that creates engineering projects.

There are additional (and more personal) reasons why you should care about proposals:

- I can assure you that becoming recognized as a good proposal manager is a sure path to enhanced career opportunities!

- Furthermore, one proven method to get the chance to be a project manager is to be the person who wins the project, by having led the proposal.

- And finally: working on proposals can be a very interesting work assignment. It is hard work with long hours, and sometimes a little stressful, but it is also intensely creative, interesting, and makes a difference to the company and to the customer.

5.2 How to Win

By now, I have probably convinced you that proposals are important. So, next I will tell you how to write proposals that can win those competitions.

We talked about internal competitions and external competitions. Here's a twist: there is always an internal competition, even when the explicit competition is external.

What do I mean by that? Let's consider a scenario:

- An organization wants to buy an engineered system, and has issued a request for proposal (actually, as we will discuss a bit later, you must start long before the customer issues the request for proposal, but for this little scenario, we will ignore that detail).

- Your company knows this buying organization, finds them reputable and reasonable, and furthermore, you think that your company has the skills and people appropriate to build the engineered system that they seem to want to buy.

- You spend some time and money gathering all of this information. You also have to estimate business‐related items, such as:

- How much revenue and profit could this project provide to your company?

- How much will it cost to win? This includes preparing the proposal, conducting negotiations, related marketing costs, and so forth.

- What are your chances of winning? Which other companies are likely to bid, and what are their skills, what is their reputation with this buying customer, and so forth?

- What people will you need to make this bid? What facilities will you need to make this bid?

- Since it will require money to make the bid (we call this an opportunity cost), you need to ask the appropriate person in your company to authorize that expenditure. They will certainly ask for information like that indicated in the previous bullets. You therefore gather all of your information, and create some sort of written artifact, and probably also get to make an in‐person presentation to the person within your company who has the authority to approve such an expenditure.

Now, put yourself in the shoes of the person who gets to make the decision: will your company bid or not bid on this job? In actual fact, this person not only has to consider the merits of the bid that you want the company to make, but this person also has to consider the merits of every other course of action open to the company at this time. For example, there are likely to be many other such bid opportunities available to the company; the company probably does not have enough money or people with the appropriate skills to bid on all of them; therefore, someone has to choose from among the options. Every possible course of action (e.g. bid this opportunity, bid this second opportunity, but do not bid this third opportunity) has its costs and potential benefits. The person with the decision authority considers all of these options – not just the merits of your potential bid – when making the decision. That is, you are in a competition against all of the other potential courses of action (and all of the other teams that have their own favorite bid opportunities) inside your company!

This is even more complicated than I just described, because not all of the opportunities competing for attention, funding, and people need to be bids; for example, someone in the company might want to spend money enlarging a factory instead of making your bid. The landscape of potential opportunities against which you have to compete in this internal competition can be very complicated.

Therefore, you must first win the internal competition for attention and funds, just so that you can gain permission to prepare a bid to the external customer.

In the little scenario above, I hinted at some of the information that you must develop in order to win this internal competition. The following is a more complete version of that list:

- Understand the problem. Who is buying it? Who will use it? By when will they need it? How many will they buy? What is it supposed to do? How is that different or better than the way they do it now? These are many of the same questions we discussed in Chapter 4.

- How to solve the problem. What will our solution look like? What will we invent or make, and what will we buy from other companies? What exists already, and what, therefore, must yet be invented in order to create this solution? How long will it take to do this research and invention process? How much money will it cost?

- How to measure the goodness of your solution. This, of course, starts with the technical performance measures and operational performance measures that we discussed in Chapter 4. But it goes on to include something that we have not yet discussed: what will be our areas of positive differentiation (e.g. where will we try to be better than the other bidders, and where will we be content to only be as good as the other competitors)? We discuss achieving such differentiation later in this chapter.

- How to prove that you can solve the problem and achieve differentiation. What will we prove by building prototypes? What will we prove by benchmark measurements in our laboratories? What will we prove via computer‐based models?

- How to show that it can be a viable business proposition. What are the business model, pricing/costing/margin, teaming, intellectual property rights and licensing, sales projections, cash‐flow projections, etc.?

If you are working at Apple, and want to build a new gizmo, something like the above may be enough to get you funding and authorization to build your team, and to start designing your gizmo. Probably, however, you will not be given enough funding actually to finish it; instead, you will be asked to come in every few months and show your progress, and to update your market assessment. If your progress is satisfactory, and the market assessment still seems credible and favorable, you have a chance to get a next increment of funding in order to do a few more months of work toward finishing your new gizmo.

If, however, you are working at Lockheed Martin, and your goal is to get funding and permission to bid on a new fighter jet contract, you are just getting started. The good news is that the company has authorized you to start getting ready to make the bid, and authorized some funding for you to get to work on the proposal. However, that is just Step 1. You still have three more steps to get through:

- Step 2. Do what is needed so that you are allowed to submit the actual bid to the buying customer.

- Step 3. Win the external competition.

- Step 4. Close the deal.

We will talk about each of these next.

A proposal is a formal, legally binding commitment. If you submit a proposal to a buying customer, and they accept it and then you both sign a contract, your company is legally committed to providing the products and services specified in the contract (and in the proposal, if the contract incorporates that proposal, as is sometimes done), and to do so on schedule, for the price, and in accordance with the other terms defined in those documents.

Because of this, companies go through an analysis and decision process before you are allowed to submit a proposal, in order to determine if – in light of what we continue to learn – they actually want to submit this bid. Step 1 (above) got you authorized to start preparing the proposal, but the company will still want to review all of the terms and conditions that will be embodied in a potential contract before letting you submit the proposal; that review is Step 2. The following list describes the typical items that you company will want to review before they authorize you actually to submit the proposal to the buying customer:

- Price to win. Of course, this is a competition, and we do not get to see the other bidders' proposals, so we do not know the actual price that they will bid. But we may have some public information about what our competitors bid on similar jobs in the past,1 and we may also have legal access to some information about how much the buying customer wishes to spend.2 Your company will want you to use that information to estimate what price the company is likely to have to bid in order to win the competition. This amount can then be compared to your estimate for how much it will actually cost for the company to build the item, and therefore the company can estimate whether it will make or lose money on the project. This will be one of the factors used by the company to decide whether or not you are allowed to submit a bid; most companies will not bid if they believe that the price needed to win is so low that they cannot make a fair and reasonable profit margin on the project.

- Time phasing of costs versus time phasing of revenues. On most projects (as depicted in Figure 1.6), the company must expend money before receiving revenue. Therefore, the company will want to understand the cash flow involved: can they provide the cash to pay salaries, suppliers, and other bills while waiting for payment from the customer? There are also a number of financial measures that the company will calculate to quantify the quality of the financial deal: for example, something called the return on assets employed, and other similar financial measures.

- Opportunity costs. To perform on your project will entail a commitment by the company of money, facilities, equipment, and talented people. The company always has the option to use those assets for other activities; to assign them to your project is to forego the opportunity to use them on something else. We call this an opportunity cost. Your company will do an assessment of what else they could do in this same time period with those funds, facilities, and people. Would those other opportunities be better for the company, and/or better for those employees?

- Risks to the company. Obviously, any project could lose money, but many other things could go wrong too: accidents that damage facilities or injure people; legal liabilities if the company is late, or unable to perform on some portion of the contract; damage to the reputation of the company; damage to the environment through an accident or a poorly designed work process; or other things that could go wrong. The company will want to assess all of these, as part of making a determination of whether they want to make this bid or not. Do we appear to understand all of the risks, and have appropriate strategies for mitigating those risks in place? (We will return to the subject of risks and risk management in Chapter 9.) Examples of such risks that must be identified, assessed, and plans for their mitigation created include:

- Capability. Does the company believe that we can deliver all of the promised capabilities?

- Schedule. Does the company believe that we can deliver all of the promised items by the promised dates?

- Price. Does the company believe that we can complete all of the tasks required by the contract for an amount that will allow the company to make a reasonable profit on our efforts?

- Contractual. Are there contractual terms in the request for proposal, or in our proposal, that the company cannot tolerate?

- Probability of winning. Writing a fully fledged proposal, and supporting the presentations and negotiations, can cost a lot of money; literally, at times, millions of dollars. So, if this is an externally‐sponsored competition, the company will want to estimate their chances of winning the competition. If this is an internally‐sponsored competition, the company will want to estimate the probability of achieving the projected levels of sales and profits.

If you get through all of this successfully, you have passed Step 2 and are allowed to submit your proposal to the buying customer. Now, you want to win! How do we maximize our chances of actually winning? This is Step 3 from the above list, and is the main topic for the remainder of this chapter. I will summarize the answer briefly now, then discuss Step 4, and finally return to a more detailed discussion of Step 3: how to win.

You will mostly likely win or lose based on what is written in your proposal. There may be some opportunities to make face‐to‐face presentations to the customer as well, but what is written is usually the main determinant of proposal success.

So, as we plan and prepare our proposal, we consider factors such as:

- Our value proposition, as expressed in the customer's coordinate system of value.

- The differentiators that we offer.

- Trust – have we earned this customer's trust?

- Contractual terms – have we offered attractive terms and conditions for the contract in our proposal?

- Schedule – are we proposing to deliver the product by the date that the customer desires? Are our claims about delivery date credible to the customer?

- Price – how much do we propose to charge? Does the customer have to pay us more than that amount if the job runs into complications, or is our company committing to absorb any such additional costs?

- Compliance – are we proposing to meet every single requirement in the request for proposal?

- Want factors – are there aspects of our offer that are attractive enough to the customer, so that they will prefer to select us over the other bidders?

Getting good answers to these items into your proposal comprises Step 3.

We will return to this aspect in a moment, but first we will talk briefly about Step 4: closing the deal.

Let's say that you win: you are formally notified by the customer that you have been selected as the company that they want to hire. You must still sign a contract. Creating a contract that both parties are willing to sign involves a lot of face‐to‐face discussion, which is termed contract negotiations. Sometimes, a customer will conduct such negotiations with all of the bidders, prior to announcing the winner; this allows them to negotiate with the contractor before they are selected, and customers think that this provides them leverage in the negotiations. It also, of course, allows the customer to be sure that the company they select is willing to sign up for contractual terms that the customer can tolerate, because they do not finalize the selection of a winner until after all of the bidders (including the eventual winner) have agreed to contract terms. Some customers, however, find negotiating with all of the bidders too expensive and too time‐consuming, and defer some or all of the contract negotiations until after they have selected a winner.

Contracts are both very detailed and legally binding, so negotiating a contract is a complicated process. You will be directly involved, together with your contract specialists and your company's attorneys.

Congratulations! You finished all four steps, won the external competition, and were able to negotiate an acceptable contract. Now you can start work.

An important insight: to do all of the above really well takes a lot of time. For a big engineered system, your company probably needs to start two or three years before the request for proposal is expected to be issued. Your company will need to pay for the team working to get ready to write this proposal for a long time.

Here is another, equally important insight: starting early is really important. The data that I have seen indicates that the probability of winning is much higher for those teams that start early, as compared to those teams that wait to start until shortly before the request for proposal is issued. Companies that enter a competition late seldom win.

And still another important insight: there will be delays along the way.

- The customer may issue the request for proposal on a later date than that indicated in their original plan.

- The source‐selection process (e.g. the process conducted by the customer to select a winner) may take longer than originally expected.

- If this is a government procurement, one or more of the losing contractors may file a protest, which holds up the awarding of the contract to the winner until an independent government agency assesses and adjudicates the merit of the claims by the losers.

What all of the potential sources of delay mean is that it will take a lot longer (and cost a lot more) than you might think to write a proposal and win a competition for an engineering project. You, your key personnel, and your company need to be prepared for the reality of how hard, how long, and how expensive this process really is. You and your company must be committed to this proposal! If not, it is better to decide early on that you are not going to make this bid, and find another, more suitable business opportunity.

We now return to Step 3: how to win. I will present two different approaches, one created by a former colleague and one created by me. You can pick and choose between them, based on what seems best for you, your company, and your particular bid opportunity.

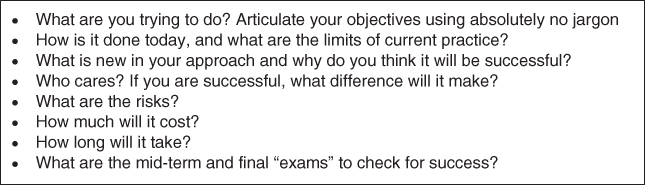

5.2.1 Approach #1: The Heilmeier Questions

For about five years,3 I served on a US Government advisory panel called the Defense Science Board.4 One of the other (more senior) members of the board was Dr. George Heilmeier. Dr. Heilmeier was a distinguished engineer, best known for having been part of the small team that invented the liquid crystal display, which is used throughout the world on millions of electronic devices. He also served from 1975 to 1977 as the director of the US Department of Defense's Defense Advanced Project Research Agency (DARPA; originally called ARPA). During his tenure at DARPA, he started using a set of questions to help people within that agency who wanted to start a project sharpen their thinking about whether or not this was actually a good project for the agency to undertake. I have seen more than one version of these questions, but Figure 5.2 shows the version presented on the DARPA website.5

Figure 5.2 The Heilmeier questions.

By the time I worked with Dr. Heilmeier, he was advocating that teams who were going to prepare competitive proposals for engineered systems use these questions to guide their planning and preparation process. That is, he advocated using them for what we are calling Step 3.

Note, however, that these questions are similar in many ways to the questions that I posed above, for Step 2.

Let's look at each question in a bit more detail:

- What are you trying to do? Articulate your objectives using absolutely no jargon. That is, what is the goal of this project? If you are completely successful, what will you have created?

- How is it done today, and what are the limits of current practice? The item that you wish to create is intended to help someone perform a mission; how do they do that mission today? This might be represented by the mission thread that represents current practice, as we described that item earlier.

- What is new in your approach and why do you think it will be successful? The first portion of this question can be answered by the new mission thread diagrams. The second portion of the question asks two separate things: why is that approach likely to be an improvement for the users (e.g. what are the operational performance measures that indicate improvement) and why is your approach to implementing that likely to be feasible (e.g. what are the technologies that you will use to implement the new mission threads, and what are the technical performance measures that indicate that it can actually be achieved).

- Who cares? If you are successful, what difference will it make? The first portion can be answered by identifying the users and other stakeholders for this mission. The second portion again can be answered by the operational performance measures. (I would put this question much earlier in the list.)

- What are the risks? That is, what can go wrong? For each of those items, if one did go wrong, what would result? For each item, how can we lessen the likelihood of such an occurrence? For each item, how can we (separately) lessen the negative impact, if in fact one of these items did occur anyway? (We will discuss these items in greater detail in Chapter 9.)

- How much will it cost? Not only how much to build and test the new system, but how much to operate and maintain it over its entire anticipated lifetime. How much will it cost to dispose of the system when its useful lifetime is ended? What is the time phasing of these costs? What is the range of uncertainty for those estimates? We will discuss this subject in detail in Chapter 7.

- How long will it take? Not only how long to build and test the new system, but also the range of uncertainty for those estimates. We will discuss this subject in detail in Chapter 7 as well.

- What are the mid‐term and final “exams” to check for success? That is, how do we objectively measure progress along the way? We will discuss this subject in detail in Chapters 10 and 11.

This is a pretty good list. As you can see, we have either discussed each subject already in this book, or are going to do so in a future chapter. Certainly, you need to address each of these items in a competitive proposal, whether the audience for that proposal is external to your company or internal to your company.

I do believe, however, that this list misses a couple of vital points, and so in order to address those particular items, I now present the method that I created and used during the time that I was writing (and winning) a lot of competitive proposals.

5.2.2 Approach #2: Neil's Approach: Achieve Positive Competitive Differentiation

My approach is slightly different. I focus on a systematic series of steps that lead to the creation of what I call differentiators, and what I call the socialization of these differentiators with the users and stakeholders, especially the buying customer. I created a sequence of steps aimed primarily at achieving that particular purpose.

What do I mean, in this context, by the term differentiation? By this, I mean creating a story line, supported by facts, so that the customer will conclude that my proposal offer is different6 from the other, competing proposals in tangible and important ways that are beneficial to the customer. Of course, to be pedantic, I should have said positive differentiation; one can be differentiated in a negative sense too. That is not what we want; we want to be better than the competition.

My view is that in order to win a competition, you must be – in the eyes of those who are scoring and evaluating all of the proposals – the best among those submitted. That is, you win by achieving relative merit (i.e. merit relative to the other bidders), not by achieving any absolute level of quality. If you are manufacturing an item, you may aspire to an absolute measure of quality (e.g. 1 defect per 1 000 000 items manufactured, or whatever), but in order to win a competition, you must be the best of those who submit proposals, rather than meet some absolute standard of quality.

What I decided during my tenure as the person responsible for winning competitive proposals was to focus on achieving this relative advantage. In order to do that, for each proposal, I defined a set of specific topics in which I aimed to make our offer clearly the best: the specific areas where I desired to achieve positive differentiation. Since one usually cannot afford to be the best at everything, I also therefore accepted that I would only be just even with the other bidders in everything else; there might even be some areas where I accepted that some other company might be better than mine. But the idea was to carefully pick the areas where I believed that being the best would cause the buying customer and the source‐selection process to choose my proposal offer over all of the others. That is, I pick the areas where I want to achieve positive differentiation and craft my proposal and marketing efforts so as to convey that message to the customer, and get them to believe it. If I choose the items where I want to achieve such differentiation properly (that is, I am able correctly to determine those items that are really most important to the customer), and I can actually convince them that I have credibly established that positive differentiation, then the customer will want my company to do the work … and we will win the competition.

This approach seems to work. Using this approach, we won far more competitions than probability would indicate. In competitions that routinely had three or four other serious competitors (and therefore, if we won only an average percentage of these competitions, we would have won 20–25% of the time), we won nearly 75% of the time, over many competitions and over many years.

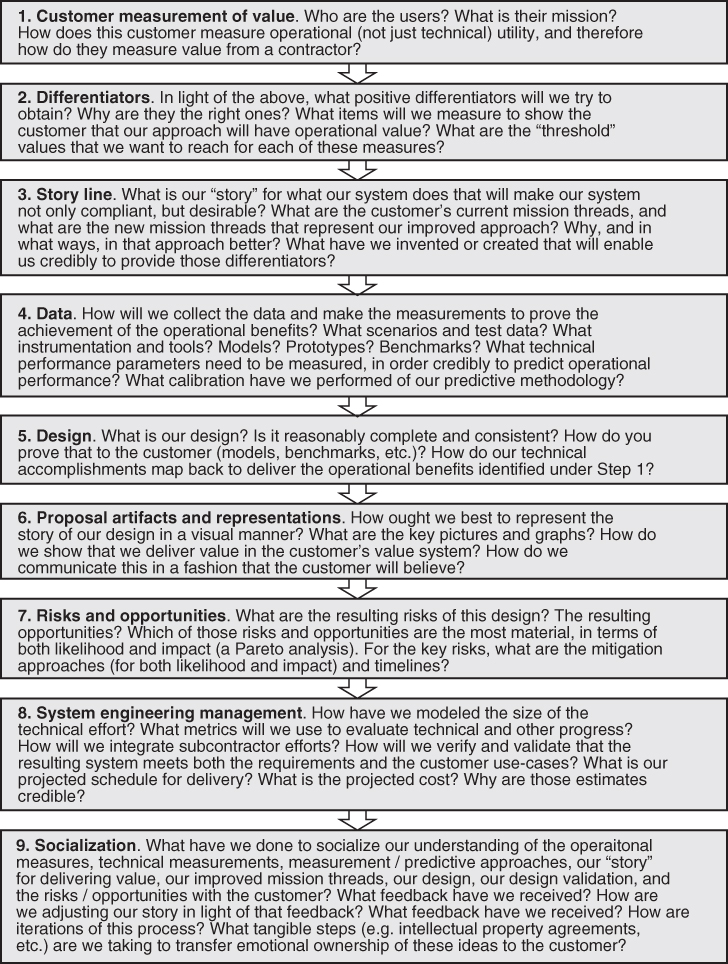

The written guidance that I created in order to accomplish this is pretty simple; it consists of just three pictures. The first is depicted in Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3 Neil's approach to achieve competitive differentiation.

First of all, you can see in that figure that quite a bit of the content is similar to that of the Heilmeier questions, although the sequence is quite different, and at times the focus. But there are also items on my list that do not appear on Dr. Heilmeier's.

As I do throughout this book, I start with the users, the other stakeholders, and their mission. We can use all of the techniques and methods that we discussed in Chapter 4 to understand the users and their coordinate system of value, and then use those insights in order to create the operational performance measures that they will recognize as measuring value that matters to them.

In the next step, I diverge significantly from the approach recommended by Dr. Heilmeier: I try to define the features of a potential design and offering that would make the customer want our company to do the work. This becomes my list of desired differentiators. I will describe below my technique for creating this list.

I must, however, limit the set of items that I place onto this list in two ways:

- I must be able to afford to implement (and have the time to implement) all of the items on the list.

- Each item on the list must not only be technically feasible, but I must also have a method for conveying that feasibility to the customer in a way that they will believe. Remember what we said previously: many of the customers are not engineers or scientists, so the explanations must be accessible to an adult of ordinary education and experience.

The idea of obtaining positive competitive differentiation from your competitors may sound obvious, but in my experience most proposal teams simply do not make such a list. It is not surprising, therefore, that the proposals that result do not convey strong positive differentiation. I believe that it is essential – absolutely the core of a winning proposal – to do this step explicitly, and to create a written list of candidate differentiators that are then explicitly discussed among the team, with your management, and (once you think that you have a pretty good list) with every element of the customer: the buying customer, the paying customer, the users, the other stakeholders, the nay‐sayers, and so forth. This is not, in my experience, common practice. But having such a list provides guidance to every person participating in the proposal, and provides your potential customers with a clear view of what you are offering. In my view, every proposal ought to do this.

The next step is story‐telling: how to tell the story about our differentiators, and their feasibility, in a clear, comprehensive, and easy‐to‐understand fashion. This is a separate step because I have found that it is often the case that the people who can identify the good candidate differentiators – and can do the technical analysis to demonstrate their feasibility – simply cannot tell the story in an effective and convincing manner. They tend to get caught up in confusing technical details. Therefore, once you have the list and the technical analysis, I have found it worthwhile to then recast the differentiators into an effective story line. This must often be done by people other than (or in addition to) those who actually create and validate the differentiators.

The next step is data‐gathering: how will we actually make the measurements that prove our story? To do that, we need at least a preliminary design, so Steps 4 and 5 go hand in hand, and may proceed in parallel.

Good proposals have more than text; they have a small number of key depictions (figures, tables, and graphs) that concisely convey our key points. We next create these depictions. We also write theme sentences (or short paragraphs) to go with each depiction. Together, the depictions and the theme sentences are the artifacts that will tell our story, both in the proposal and in our face‐to‐face interactions that lead up to the formal submission of the proposal, and the eventual selection of a winning contractor.

Steps 7 and 8 are similar to several of the steps that are included in the Heilmeier questions. What could go wrong, and how do we mitigate those risks?7 How will we evaluate progress?8 How long will it take? How much will it cost? (Notice that I will always discuss schedule before cost; I will tell you why in Chapter 7, and revisit the subject in Chapters 10 and 11.)

The last step – Step 9 – is another step that I have found is often done poorly. It is not enough for us to create great differentiators; we must get the customer actually to believe them. In my experience, explaining these great differentiators to your customer for the first time in the proposal is not sufficient in order to get customers to believe in your differentiators. In order to get them to believe in those differentiators, we must socialize those differentiators (and our other key ideas too) via face‐to‐face meetings with the customer before we submit our proposal. We do this for two reasons:

- First, we are likely to learn something from such interactions with the customers that allows us to refine and improve our differentiators, and our other ideas.

- Second, people are always reluctant truly to believe other people's ideas; they are far more likely to believe an idea if they feel that they have had a hand in creating it. You therefore need to allow your customer to have intellectual skin in the game of creating your differentiators. I like to say that we must transfer some emotional ownership of our ideas to our customers; if we can make them feel that these ideas are in part theirs, they are much more likely to believe in those ideas, to accept the arguments that led to them, and to accept the inferences that derive from them. That is what we want!

The value of your differentiators must be measured in the customer's coordinate system of value, not just in the engineer's coordinate system of value. We have talked about this before: customers are seldom engineers or scientists, and therefore have a different “coordinate system of value” than we do. Therefore, if we want them to like our ideas and select our proposal (especially if we want them to like us so much that they will pay a price premium to get us – always a great aspiration), then we must convey our value proposition in their coordinate system of value. We are engineers, so we measure things … even when they are in the customer's coordinate system of value.

Here's a little complication: almost always, there is more than one “customer.” There will be multiple influential people within the buying organization, multiple influential people within the user's organization, and multiple influential people in other places. We must therefore determine the “coordinate system of value” for each of these people and/or groups. Usually, the needs and desires of these various groups will be in conflict in some ways. We must resolve that, through balance; we must convince them that our proposed balance is the best possible outcome.

That seems like a lot of trouble. Can't we just ask the customer what would constitute a set of differentiators?

The conventional wisdom, of course, it that “the customer is always right.” My view is different: my experience suggests that many customers are so busy operating their mission that their view of the future is “three minutes from now.” They know well what they do now (and you should learn from that), but you usually cannot depend on them to create an effective vision for revolutionary future improvements.

In any case, if they did it for you, they would have to share that information with all of your potential competitors (in a competition, the customer will try to be sure that they are providing all of the bidders the same information, so that the competition is fair). And, since all of the potential bidders could avail themselves of that knowledge, this would deprive you of any potential differentiation from your competitors!

But if you create a vision for the future for the customers – and then convince them that it is valid, valuable, and feasible – they need not share that information with the other bidders, and therefore the differentiators that we create can provide you with competitive differentiation.

Now let's return to the meat of the discussion: how to choose those desired differentiators.

When the competition is finally over, the customer will have a set of reasons for why they selected a particular offer. In competitions for US Government contracts, the Government will actually tell you in advance what the “source‐selection criteria” are going to be:

- It might be price. City governments do this when buying a commodity, or a low‐tech service (such as repairing potholes in streets).

- It might be the lowest price among those technically acceptable. In this situation, bidders whose offer does not seem credible, who don't have qualified people, who don't seem to understand the problem, and so forth, are eliminated from the competition before the customer looks at the prices offered by each bidder. They will then select the lowest‐price bidder among those left.

- For most engineered systems, however, the source‐selection criteria are something more complicated: an approach called best value, which consists of what – in the judgment of the customer – seems to be the most advantageous combination of price, capability, risk, schedule, credibility, and contractual terms.

Since the customer has criteria for how they are going to select the winner, you must be able to credibly show that your proposal is superior in a set of factors (some of which are quantifiable; price is certainly quantifiable) that relate to those criteria. And remember the want factor too. You therefore need differentiators for each of the following:

- The explicit source‐selection criteria

- The unstated source‐selection criteria

- The “want factor.”

The general process for selecting differentiators that I use is as follows:

- Understand the customer's point of view:

- What they do now, and why they do it that way

- What they have tried and rejected in the past

- Their “unwritten rules.”

- Use this to derive a statement of what they value.

- Use that to create actual quantifiable metrics (the operational performance metrics) that can express the goodness of a candidate solution in their coordinate system of value.

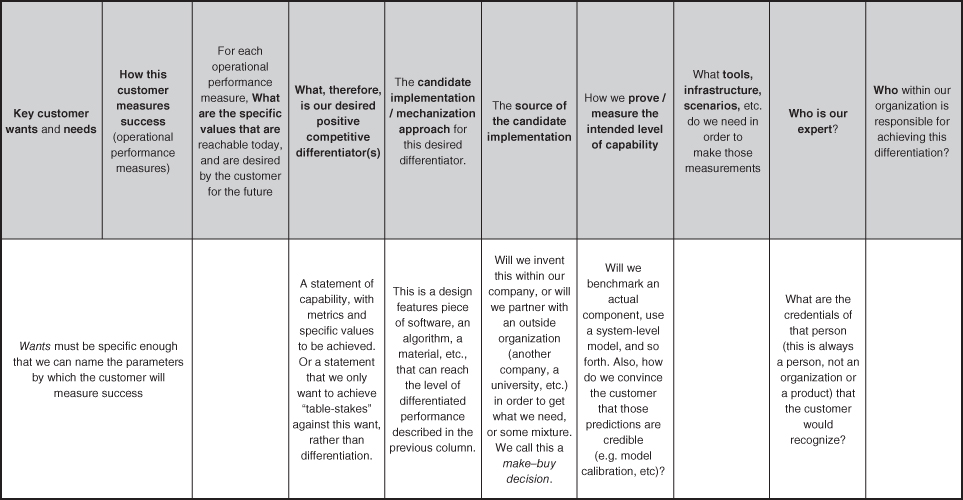

- Now that you have metrics that reflect the customer's coordinate system of value, you next (and this is the critical step) create ideas for what the system ought to do to score well against those metrics; these are the core of your potential differentiators. I do this by creating alternative versions of the mission threads, and by working through the process depicted in the matrix that constitutes Figure 5.5.

- Socialize the above with the customer, continuously.

You must plan where you want to achieve differentiation. You must figure out in which factors you want to be superior, and in which factors you are content to be even with the competitors (it might cost too much to be superior in every factor). Those factors where you intend and plan to be superior to all other competitors are your intended differentiators; you might prioritize your differentiators, so that you have primary differentiators and secondary differentiators (Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4 Factors that can help you create positive differentiation for your proposal.

Remember, if the customer has identified something as an explicit need (usually, by writing a mandatory requirement), every bidder will claim that they are doing that. Therefore, the mere fact that you are meeting a requirement cannot be a differentiator. It may be, however, that there is something superior about how you are implementing that requirement (e.g. something about your design that lowers risk, provides more design margin, or some other characteristic that is of benefit to the customer). That how may be an opportunity for differentiation. This is a frequent mistake that I see teams preparing competitive proposals make over and over again: they believe that the mere fact that they are meeting a mandatory requirement can constitute a differentiator. That is never true.

One way to test the effectiveness of your candidate list of differentiators is to write the briefing slide that you imagine the customer would use to brief their boss about why they chose you over the other competitors.

To guide the overall process of creating and proving differentiators, I use the matrix depicted in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5 The matrix that I use to plan competitive differentiators.

The first column lists the key customer wants and needs. These, of course, are usually measured by operational performance measures, rather than by technical performance measures. The matrix works its way through a series of topics and questions; when you have completed every column for each of your desired differentiators (e.g. one row per differentiator), you are ready to start socializing them with your customers.

Examples of questions to ask the customers during the socialization process are:

- “If we could do this, would it help?”

- “What would constitute adequate proof that this idea is credible?”

Such socialization is a long‐term process, never accomplished in a single meeting.

A word about where to look for potential differentiators. I find that most people today think that competitive differentiation comes from improved technology. I believe that this is generally wrong, on two counts:

- Technology by itself tends to provide small, incremental improvements (this year's disk drive has 15% more capacity than last year's, and costs the same). But systems are expensive, and no one buys big expensive systems to get small incremental improvements.

- And even if a specific set of commercially available technologies provides a big improvement, they are probably available to the other competitors, and therefore do not provide competitive differentiation. You must look elsewhere for the differentiation that you need in order to win.

Of course, if you have a proprietary technology, that will not be available to your competitors. But the first point still applies; my experience is that big improvements tend to come from changing the business process of a mission (which we represent in the mission threads), rather than solely from improved technology. This is not at all the “conventional wisdom,” but that is fine by me; it gives me the opportunity for differentiation from my competitors!

Let me say that again: in my experience, instead of coming from technology, the differentiators seem to come from improvements to the mission threads. Only after you have created the specific ideas for what the system must do in order to create that differentiation (by creating the new mission threads) do you start to think about technology. The role of technology is seldom to create differentiation; instead, it is to make the implementation of your desired differentiation feasible. Your differentiation comes from the improved mission thread; that will usually relate directly to the operational performance measures, and therefore be credible to the customers.

Having differentiators is necessary, but not sufficient. The step of socialization with customers is also vital. As I have said previously, most of us can be counted on liking our own ideas, but are far less open to the ideas of others. Therefore, in order to get the customer to like your idea, you need to allow it (at least, in part) to become “their idea.” My phrase for this is that I want to transfer emotional ownership of the idea to the customer. Then it is (at least in part) “their idea,” and they are far more likely to fight for it!

There are many ways to accomplish the transfer of emotional ownership:

- Joint brainstorming

- Collaborative research, under some sort of formal agreement

- Grant generous intellectual property rights

- … and many, many others.

A few examples of actual differentiators will probably help. Here are some that I have created over the years:

- Example 1. Prescribing drugs

- Desired differentiator: Significantly decreased number of deaths due to adverse interactions among multiple prescription drugs taken by a patient.

- Associated operational performance measure: Patient deaths per year in the United States, due to adverse interactions among prescription drugs.

- Discussion: When we started, the number of deaths due to interactions among prescription drugs in the United States was estimated to exceed 100 000 per year. We were able to show that our improved system for managing and monitoring the prescription process would avoid a majority of of those deaths. As a result, our approach was eventually adopted, despite intense resistance by doctors.

- Example 2. The US Army's Blue‐Force Tracker

- Desired differentiator: Significantly improved land combat power, at a modest cost (e.g. a small percentage of the cost of the brigade's equipment, and far less than competing approaches to obtain a similar increase in combat power).

- Associated operational performance measures:

- The loss‐exchange ratio, a direct measure of improvement in combat power.

- The ratio of the cost of fielding the Blue‐Force Tracker to the entire Army, versus the cost of upgrading every tank in the Army.

- Discussion: We were able to show that the Blue‐Force Tracker would provide far more increase in combat power than a particular anticipated upgrade to the fleet of tanks. After conducting its own modeling efforts, and a series of large‐scale, unscripted, force‐on‐force exercises, the Army accepted this estimate. The Army's own assessment showed that the anticipated cost of developing and fielding the Blue‐Force Tracker to the entire Army was far less than the anticipated cost of fielding the upgrade to the tanks. As a result, the Army funded our Blue‐Force Tracker, and elected to upgrade only a small number of the tanks an Army‐wide upgrade of the tanks.

- Example 3. The US Army's short‐range air defense

- Desired differentiator: Significantly increased number of enemy aircraft shot down, while still never shooting down a US aircraft

- Operational performance measures:

- “90% of the time, the correct target shall be in the narrow field of view of the weapon's optic, and correctly enter auto‐track” (remember Chapter 2!)

- Ratio of achieved shot opportunities (that comply with the rules of engagement) with and without the system, against a set of standardized scenarios.

- Discussion: We were able to show a better than 5× improvement in the number of shot opportunities achieved for a set of standardized, realistic scenarios, as proven through free‐play field exercises, while also meeting the “90% in the narrow field of view” measure, which ensured that US aircraft would not be shot down.

This creation of differentiators all sounds pretty complicated. Why not instead just aim always to be the lowest‐priced bidder?

First of all, you might be the lowest‐priced bidder and still not win. If this is a best‐value competition (as are most competitions for complex, engineered systems), and I have made the customer want my system through the creation of strong and credible differentiators, I will likely win even if your price is lower than mine. I once won a large contract for an engineered system, even though my bid was for twice as much money as any of the other bidders. Also notice that most of the cars sold in the United States are not the lowest‐price model, and that Apple sells more phones that their lower‐priced competitors. Lowest price is not a reliable path to winning!

Furthermore, life is not always pleasant for those who aim to win only by being the lowest‐price bidder. You might be forced to bid such a low price that you can't make a profit; you can't pay your employees enough to attract and retain good talent; you can't provide benefits (vacation, retirement, sick‐pay, medical insurance, suitable offices, etc.) to your employees sufficient to attract and retain good talent; and so forth. In my experience, you cannot build a great business around only being low cost.

But what about WalMart? Didn't they do exactly that? Actually, no. They do use their automated supply‐chain management tools to try to achieve costs below their competitors. But they do many other things too; things that cost a lot of money, and thereby actually drive up their prices! For example, they have lots of locations, because they believe that having locations nearby is convenient for (and important to) their customers and potential customers. They also do many things that they believe improve the quality of the shopping experience: lots of free parking, greeters at the front of the stores, lots of checkout lines, no‐hassle return policies, and many others.

They clearly believe that these items (even though they drive up their prices!) are an important part of their selling strategy – their differentiation! They pioneered many of these things, most especially the no‐hassle return policies. I believe the most important single ingredient to WalMart's original success was their no‐hassle return policies, not their prices.

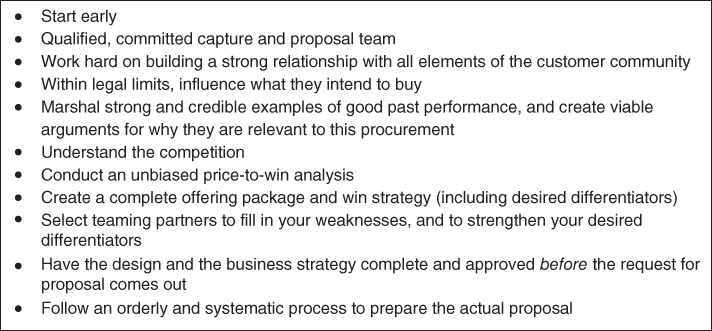

Figure 5.6 summarizes my key suggested steps to winning.

Figure 5.6 The key steps to winning.

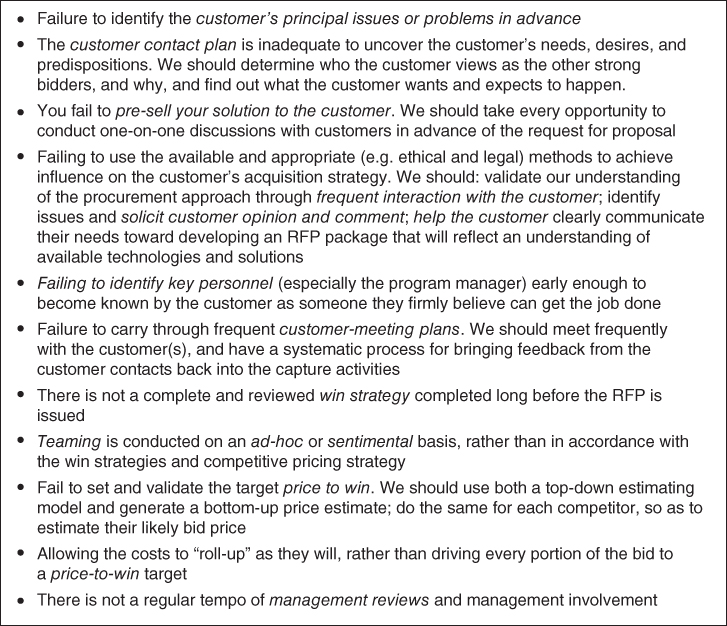

In contrast, Figure 5.7 summarizes some of the typical mistakes that I see over and over again; these cause you to lose competitions for project contracts that you could have won.9

Figure 5.7 Typical mistakes made during competitions.

While we are talking about mistakes, I want to say something about the topic of past performance. The buying customer for a complex engineered system will certainly want to understand how your company has performed on previous contracts. Did you finish the contract on time? On price? Did you deliver everything that was promised in the contract? Did the users find the system suitable, as well as effective (remember that we defined these terms in Chapter 3).

The buying customer will also try to determine if some of these previous contracts on which your company has performed are relevant as indicators of how well you are likely to perform on this contract. Are some of those previous contracts of the same order of size and complexity as this new system? Do some of those previous contracts involve similar capabilities and/or make use of similar technologies as this new system? Are there portions of those previous systems that can credibly be repurposed by your company for this new system? Are some of the key technical personnel that contributed to the success of those previous projects committed by name to this new project? Your company is likely to be claiming all of these things, in order to show that you will be a reputable supplier, and that the low price you are bidding is credible.

In my experience, however, companies often seriously hurt their proposals through overly broad and overly generic claims about past performance.

How do proposal writers hurt themselves in this manner? First of all, customers are in fact not particularly interested in the fact that you solved some different problem for a different customer; they want only to know about your approach to solving their problem. They will also want to know why your approach for doing so is feasible and credible.

Therefore, you must tell them first how you will solve their specific problem; this is based, of course, around your design for their system, and your methodology for organizing and conducting the work: the tools you will use, and so forth. Past performance has nothing whatsoever to do with establishing this part of your proposal story.

Then, you must convince them that your design and methodology are feasible and credible. This is where past performance comes in: you successfully built the XYZ system for customer ABC last year, and it uses three of the same critical algorithms as you are proposing for this system. This provides a credible method for you to show the performance of those algorithms: you can run actual benchmark assessments on the XYZ system. This shows that your staff know how to properly code those algorithms in software. It might even back up your claim that you can reduce risk and cost a bit (but don't exaggerate how much) by reusing some of that software in the new system. And so forth.

What is to be avoided is the overly broad claim (e.g. “Our company built the XYZ system, so of course we can build your system”). The customer only cares about their system, and is far less willing to believe than you might expect that the experience of building the XYZ system for a different customer will be relevant to their system. You must prove, via tangible examples, every single step of relevancy, as described in the previous paragraph. If you are too broad in your claims, or too generic, you will create an air of charlatanism among the buying customers and the users, and end up not being believed, not just about past performance, but in other portions of your proposal too.

5.3 Your Role in All of This

Among all of the people involved in winning proposals for engineering projects, there are three key roles:

- The capture manager. This person is the strategist, the person who leads the effort from the earliest days of identifying or creating the opportunity, through the internal efforts that assess the opportunity, the shaping of the opportunity through continuous interactions with the various portions of the customer, the definition and validation of the desired differentiators, the qualification of the opportunity (that is, does our company, based on all of the factors described in this chapter, in fact want to make this bid), the selection of the designated project manager and their socialization with the customer, the selection of the proposal manager, and so forth.

- The proposal manager. This person is the one who actually leads the efforts to prepare the written documents that respond to the request for proposal.

- The designated project manager. This person is the one who will become the manager of our engineering project after we win.

On a proposal effort for a large project, these are likely to be three separate people. As is usual in systems engineering, there is tension between these people. For example, the capture manager wants to win, and will therefore be looking for ways to decrease the price that the company will eventually bid, in order to increase their chance of winning. But the designated project manager knows that he or she has actually to execute the eventual contract, and will press to ensure that the price bid is high enough to provide adequate resources to do the work. This tension (and there are many other examples of such tensions between these three people) is healthy!

For projects of a more moderate size, the designated project manager may also assume one of the other roles. But in this case, someone else must be appointed to focus on achieving a balance among the factors in tension; for example, if the designated project manager is also the capture manager (I have performed this double role at times), someone must be designated to be the person with the authority to ensure that the price bid is high enough to provide adequate resources to do the work.

As the capture manager, proposal manager, and/or designated project manager, you of course organize all of the tasks described in this chapter, select the people who will lead each task, and ensure that they then follow through on the execution of those tasks.

You must also personally be involved in the creation and validation of the desired differentiators. Since many of those differentiators describe desired characteristics of the design for your system or product, the creation of differentiators involves the use of engineering techniques and skills; this task cannot be performed by sales &/or marketing personnel.

5.4 Summary: How to Win

- Virtually 100% of company revenue comes as a result of proposals

- Either competitive contract awards, or

- Internal competitions to select our next product.

- Becoming a recognized good proposal manager is a sure path to career opportunities.

- There are recognizable steps to win:

- Some focused internally. Reduce risk, don't sign up for a bad deal, etc.

- More focused externally. What does the customer need and want, how do I obtain differentiation, etc.

- Obtaining credible differentiation is the key

- We are engineers, and we measure this too

- Persuasion! Transfer emotional ownership of your ideas to the customer.

And finally, a personal note. I loved running proposals. I felt that I was making a difference to the company and to the customers, it was interesting, and it was intensively creative. Maybe you will love working on proposals too!

5.5 Next

Now that we know how to win a competition, you are ready for day‐1 of your new assignment as the manager of a new engineering project. What do you do first?

5.6 This Week's Facilitated Lab Session

- You will continue working in your teams. Today's topic is team exercises about proposals and how to win.

- Today's assignment for your team:

- Refer back to the project that your team selected during the week‐4 facilitated lab session.

- Someone is going to have to make a decision about whether or not to select your team to build the product you defined; that might be either an internal or an external customer. You will therefore be facing the prospect of having to enter a competition, and having to win that competition.

- Create a short list of desired differentiators for your project. Explain how each relates to the operational performance measures that you created last week for your project.

- Answer the Heilmeier questions for your project.

- Hold a group discussion of your findings and insights.

- Get together outside of class and write this all up (three to five single‐spaced pages of text and figures; full sentences and paragraphs, rather than bullet points). This will become one section of your final team report that will be turned in as homework near the end of the term

- You will also need to prepare a couple of briefing charts summarizing this topic, for the presentation by your team during the last week of class.