4

The Battle for Trust in the Digital Age—The More We See, the Less We Believe

Trust is the glue of life.

It's the most essential ingredient in effective communication.

It's the foundational principle that holds all relationships.

—Stephen Covey

In the 1950s and 1960s, we were very much in the Mad Men era of marketing, which was all about being clever and resonating with people who you intuited or divined were your audience. There were lots of broad statements made about large segments of the population, such as the familiar “What's good for General Motors is good for America” or this 1964 ad for Samsonite Silhouette luggage: “Silhouette is you … slender, fast-paced, daringly elegant.”1

These statements and slogans were the fundamental elements of trust. Customers received the brand promise—it was usually simple, and the reality of the experience might have been hit or miss. Reviews, forums, social, and modern channels didn't exist for consumers, so you relied on authoritative figures or pitchmen to provide the confidence.

In truth, the American population was not as homogeneous as marketers thought it was, and people weren't quite as receptive to the kinds of broad statements that many marketers were routinely making. As it turned out, the American Dream could be segmented into a lot of different pieces. In addition, the concepts of need states and behaviors versus expectations also came into play, further parsing customer segments.

As the digital age started to take hold, the premise of a universally held brand promise that everyone trusted became increasingly hard to maintain. Given all the outlets for customers, employees, and other influencers to share and compare experience, a brand today is what your community of interest says it is and it's only as good as the preponderance of evidence may suggest.

Initially, marketers and business leaders thought about only one side of the equation (in the traditional terms, the one they knew—broadcast marketing), “Ooh, marvelous! For the first time we can get all this data on people, and with it we can pinpoint our marketing messages to them more directly.”

With the advent of email (many observers mark the birth of digital marketing to the day in 1971 when Ray Tomlinson sent the very first email message), and as we add more channels to the mix, what made digital marketing different from traditional marketing was primarily the delivery method. Unfortunately, for all the promise, what stayed the same was the old-school thinking firmly rooted in the early-twentieth-century mindset. That never really shifted.

Marketers thought, “If we only had this data, we would be able to do everything and be mega successful.” In truth, it's a lot harder than that. It's not so much about how many pieces of customer data you can accumulate—gigabytes, terabytes, petabytes, and so on. It's about the context, it's about where someone is in their decision-making and in their journey, it's about who gives them the confidence to buy something or to engage with a brand. As powerful as the insights we gain from analyzing marketing data can be, there are still a lot of things going on in the human mind that can't always be accounted for just by getting a better database.

Even now, you can see that with every new channel, with every new social, modern channel account platform, the stakes and the lexicon that marketers use is still the same: How do we define success through reach or how do we define success through engagement? But what's lost in that is the idea that if only we knew a little bit more about the customer, we'd be able to reach them with the right marketing message, with the right offer, with the right product or service.

And in truth, it has turned out to be frightfully more complex than that. But this sort of vision for the future still exists—just as it did in the post-World War II period—that Americans' lives would be so much better. We would work less, be happier, and all these remarkable new technologies would make our lives simpler and better. Well, this vision didn't exactly pan out the way it was supposed to. The truth to the contrary, these new technologies, one could argue have made our lives more complex, more disrupted, and less fulfilled while undermining trust.

When you look back across fairly recent history, the introduction of major new technologies has often been accompanied by much trepidation and warnings based on the anticipated disruption they were predicted to cause to the social fabric. There is a natural fear and skepticism. Indeed, with each new technology came potential resistance for fear of what it might do to society, to industries and social structures.

Soon after telephones started to become widely available, there were concerns that this new technology would increase the speed at which people would have to react in their day-to-day interactions. According to an article in an 1899 British newspaper, “The use of the telephone gives little room for reflection. It does not improve the temper, and it engenders a feverishness in the ordinary concerns of life which does not make for domestic happiness and comfort.”2 In other words, telephones might steal away a bit of our humanity—perhaps turning us into unfeeling machines or automatons.

Of course, more recent major technologies have also been accused of being disruptive to the social fabric (which has already been disrupted numerous times by previous tech innovations). While texting in particular has attracted much concern—from distracted drivers to distracted mates to distracted students—the same has also been true for the arrival of email, the internet, and the social web. In each case, people become more closely wedded and attentive to their electronic devices than to the people sitting right next to them. Again, one could argue, a bit of our humanity is stolen by the next technical gadget or medium—at least that's the concern voiced by many observers.

You could certainly make the argument that every consumer technology has isolated us a bit more, despite all the many benefits each has brought to us. The vision for product developers and manufacturers has been to make our lives better and easier, and for marketers, to make their messages more targeted and more impactful. But in reality, all the technologies we're using are changing to a certain degree the way we relate and interact and think—how we prioritize certain things that we used to take for granted. Our technologies are changing us and how we see and interact with the world and with those around us.

And then consider the impact of major disruptions not of our invention, such as the COVID-19 virus. Employees who used to be in close quarters with one another were suddenly torn out of their offices and workplaces and moved into their homes—often with spouses and children who had been torn out of their jobs and schools. This change in social dynamics, which occurred almost literally overnight, was facilitated by digital communications platforms such as Slack, Microsoft Teams, and Zoom. And it's fundamentally changed how business leaders think about the future of work.

I'm sure a lot of business leaders are thinking right now, “Hey, we kinda got away with not having everybody in the office—maybe we can keep this good thing going.” Of course, there are others who think the reverse, “We've got to get people back in the office as quickly as possible—they're not getting as much done working at home!” And workers are often caught in the middle. Many now expect to be able to continue their remote work status, and if they can't, they assume it's because their employers don't trust them.

All this could be chalked up to the change that circumstances force us to confront, but it also requires us to stop and think about the long game. Do we go with the flow because we are riding the next big wave, or do we have an obligation to question and make a concerted stance on what we believe is good for customers, employees, and society, and how we will therefore act? This is the new brand promise, and how we frame it will directly affect how trusted we are as an organization.

We're at a surprising split in many ways between what we thought the digital vision of the future would be and where we actually are today. We thought all this data would make our lives so much easier as marketers, as business leaders, as communicators, but in truth it's just made things more complex and uncertain. Now we need to think more carefully about what kind of data is important and to separate the wheat from the chaff and get rid of the unimportant data because it gets in the way.

We also, more than ever, need to agree how we use data, how we manage it, what promises we make to customers and employees, and how we follow through on those promises. Technology and data are two-way streets; the more data collected, the more opportunity for misinformation, the more uncertainty around what a brand stands for, the more opportunity for mistrust.

People are clearly anxious about how data about them is used. Accenture's Tech Vision research revealed that two-thirds of consumers (66 percent) say they're as concerned about the commercial use of their personal data and online identity for personalization purposes as they are about security threats and hackers.3 According to a McAfee survey, 43 percent of people feel they lack control over their personal data, and 33 percent aren't certain they can control how businesses collect it.4 People are also concerned about companies that link their data to advertising. Seventy-seven percent of respondents in a 2019 survey reported that they were uncomfortable when they noticed targeted online ads.5 Not only that, but according to an RSA Security global survey, only 17 percent of people consider personalized ads to be ethical.6

Results like these are a tremendous problem for companies, and it shows just how much trust consumers feel when they are on the receiving end of personalized online ads. When people don't trust a company, they will seek out companies they do trust. In fact, an Accenture survey found that 58 percent of consumers reported they would switch 50 percent or more of their spending to companies that provided excellent, personalized experiences that did not compromise their trust.7

Many businesses are taking positive steps to shore up the trust consumers feel toward them. In just one example, quick-serve giant McDonald's is providing employees greater control over their workplace, allowing them to change menu displays based on local conditions, utilizing live traffic data, observation of peak customer demand, and more.8 This change at McDonald's promises to make the experience better for both customers and employees.

We have to think about the different types of data we gather as the key for understanding the needs of a customer. No matter what you do or how clever you get with the data—you can conduct all the multivariate analyses and regressions you like—at the end of the day, if you ignore the basic principles of what makes us human, you do so at your own peril. And you miss a tremendous opportunity to humanize digital.

The Great (Digital) Divide

The digital divide is often talked about in socioeconomic terms—the people who can afford the hardware required to access the internet, and those who cannot. That's not the kind of digital divide I'm talking about here. At the 50,000-foot level, there's the digital divide that separates us as humans from the machine world. The machine world keeps growing and we keep trying to perfect it, and we erroneously think that it's predicated on understanding every aspect of human behavior through data.

But there's still the human, nondescript, poetical side of the divide, which is hard to quantify in purely mathematical terms. This side of the divide owes more of its origins and its power to the fact that human behavior is incredibly complex and constantly changing. However, there are things that don't change because they're specific to our species. There are things that we have accreted over time that prevent us from being a perfect fit for whatever marketing models someone comes up with. As a result, despite all we do to organize ourselves and organize society and organize our customers, we're in truth not very organized at all. Trying to organize that chaotic bit on the other side of organization is what creates a stark demarcation line between the digital world and the human world.

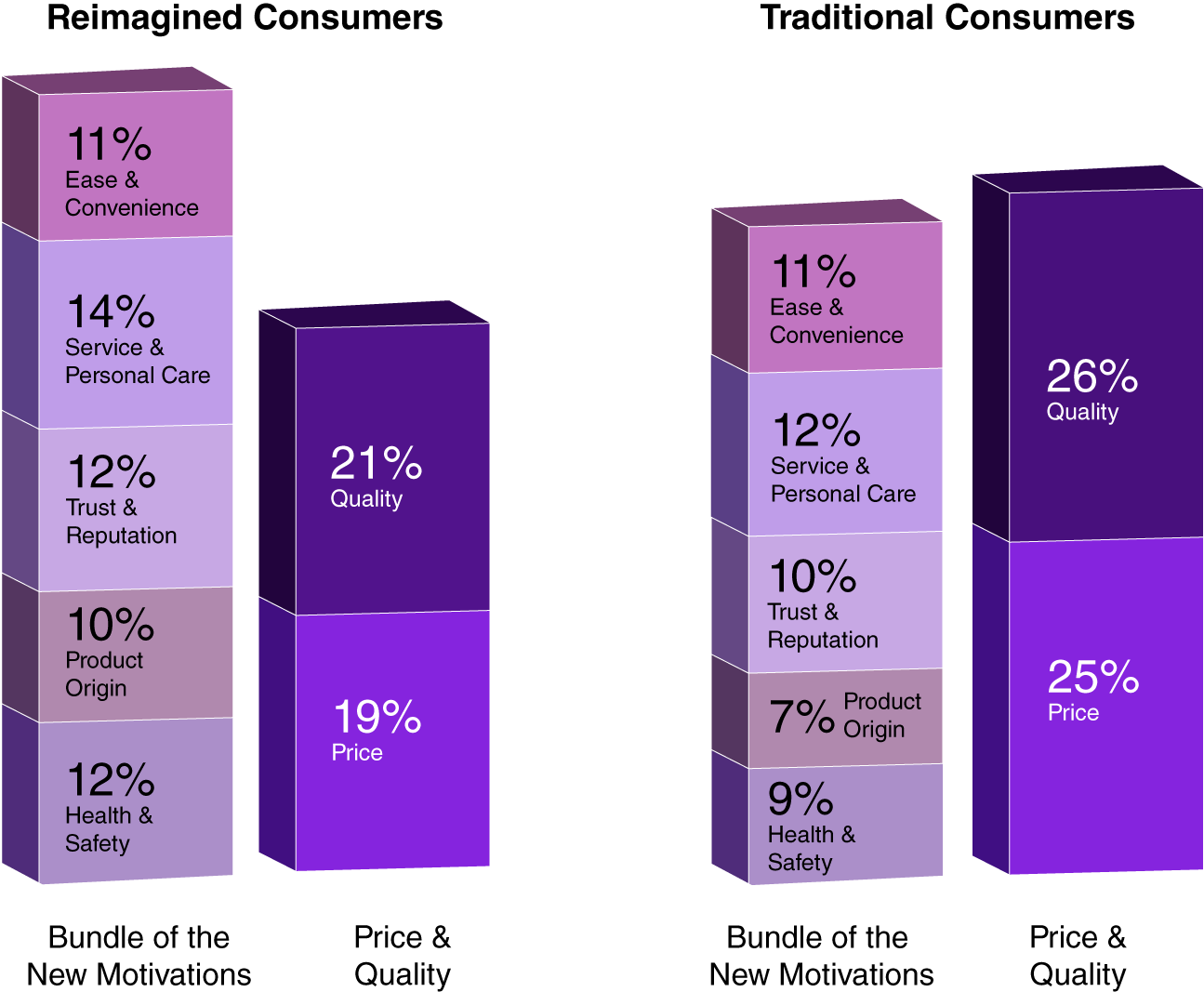

The divide creates an omnipresent tension that I don't think people pay a lot of attention to. The tension is there when we see something that's an outlier, such as a massive data breach that outrages millions of customers, or we visit a website and it feels kind of creepy because we're getting asked a lot of personal questions, or we engage in a debate about how much of our so-called personal information is actually personal. See the visualization below on the five rising areas of consumer motivation when making purchase decisions.9 These five rising areas are quickly displacing quality and price, and they're at that demarcation line between what's digital and what's human. As such, if not addressed adequately by brands, they have the potential to undermine faith in the business and its products or services.

But what if you pivot away for a moment from the struggle between digital and human, and instead think about the two being blended together as one and the same? Once we accept that the first order of importance for any organization is to support the human, not the data, then how do we make the digital experiences we have conform to something that's a little bit more fluid and a little bit more abstract and a little bit more humanized—something that really works in terms of engaging customers and citizens?

At every point in human history, there's been distrust of the machine. One group might call each successive technology progress while another group might call it disenfranchisement. And it never stops. From the telephone to email and texting to social media to the internet of things to artificial intelligence—that tension has always been there and there's always going to be that debate. The challenge for bringing detente is being able to make sure that one aids the other, rather than the other way around.

I believe that right now we are at an inflection point. There are some very weighty issues plaguing us because of our digital progress as humans, and it's not certain which paths we will take and if they will turn out to be the right ones.

How far does digital lead us away from our natural instincts as humans, and does it support us or does it threaten us? You would think that by having digital experiences that help people discover things, help people learn, help people connect—you can go down the list of 30 different things that digital can do—that weight of digital would clearly be overwhelmingly on the side of good. But there's a polar element to it that we struggle with, which is that, for as much information as digital brings to us, it now also raises the specter of whether we can trust that information. How do we know that what we're discovering is actually true?

We used to enjoy and be entertained by marketing messages, but now we're starting to get the feeling that they're insidious, invasive, perhaps even a little bit evil. For the most part, we increasingly ignore them, so all the effort and investment is falling on deaf ears. But when we do pay attention, we think marketers might just know something about us that we don't know about ourselves, and that can be really scary. When they follow us all around the internet, when we buy something—or think about buying something—and all of a sudden we're getting targeted marketing messages. When they keep trying to sell us what we already bought, it can feel like Big Brother is watching us very closely. In fact, a 2020 survey of consumers in the United States, the UK, Australia, Spain, France, and Japan reported that two-thirds of respondents felt that ads that followed them across devices were “creepy.”10

Then there's the whole issue of who controls technology and for what purpose. We like to think that the internet was constructed as a happy-go-lucky, open-source fount of all wisdom for everyone. And originally it was—that was the charter. There were a bunch of well-meaning scientists and engineers who created a vision for the internet, and their goal was to make it noncommercial and open for everyone to use. It was very Summer of Love. Everyone felt empowered because they didn't know much about it, and no one knew much about it, and so the playing field was somewhat equal.

But as every technology proceeds, that equality naturally erodes and we arrive at a place where some people and organizations are more equal than others, while the vast majority are less equal. I don't control the internet. I don't control my internet service provider (ISP). I don't know what an ISP is. I don't know who has data on me. I don't know how they got that data on me. And I don't know how to manage that. I don't even know what it's worth. The fact of the matter is people are feeling less and less in control.

The same thing is true when it comes to social media. When social media took off, I was one of the first people to get excited about its promise. I was certain it would promote transparency and civil behavior. I think a lot of people believed that at the time. But as time has passed, we've seen over the past 10 years that more people are aware of what you can do with it—for both good and bad—and how you can manipulate and use it for your own benefit. There's a narrow band of people and institutions that can do that, while the vast majority of us cannot.

According to the Oxford Internet Institute's 2020 media manipulation survey, organized social media manipulation campaigns were found in all 81 of the countries surveyed—an increase of 15 percent over the previous year. In addition, the survey found that more than 93 percent of countries surveyed deploy disinformation as part of political communication. Says Oxford Internet Institute director Philip Howard:

Our report shows misinformation has become more professionalized and is now produced on an industrial scale. Now, more than ever, the public needs to be able to rely on trustworthy information about government policy and activity. Social media companies need to raise their game by increasing their efforts to flag misinformation and close fake accounts without the need for government intervention, so the public has access to high-quality information.11

You can see now where institutions and people who might have an alternative agenda have started to figure out how to play the angles. The result of that is increasing suspicion and distrust, uncertainty about who or what to believe (what is fact and what is propaganda), and a nagging suspicion that in the overall scheme of things, we can trust no one. We are confronted with the devastating realization that we don't matter all that much as individuals.

It's clearly in our interest as marketers, business leaders, and government leaders to close this digital divide, and to build trust with our citizens, customers, employees, partners, investors, and the communities in which we do business. I would argue that it is essential if we are to continue to advance as a society—together, not divided. As partners, not tribal adversaries.

The Threat to Markets and Capitalism

When technology is used for good—understanding that the definition of good is relative and subject to debate—it's readily apparent that it opens up doors and creates all kinds of new opportunities for people in all walks of life, young and old, in communities and countries all around the world. That's as true today as it has been for the past many thousands of years of human history. When early humans discovered how to make and contain fire, that led to much good—from cooking to creating warming fires to tool-making and much more. It helped us elevate ourselves from mere primates to rulers of the earth. Of course, in the hands of an arsonist (or the errant hooves of Mrs. O'Leary's cow), fire can also be a bad thing—destroying everything in its path.

The same is true for new technologies such as social media. Facebook has enabled billions of people around the world to forge digital connections with one another—to, in words of the company's mission statement, “give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together.”12 But the social media giant also, beginning in 2014, enabled Cambridge Analytica to harvest the personal data of more than 50 million Facebook users without their consent. The data was eventually used to great advantage by the successful presidential campaign of Donald Trump—microtargeting 10,000 different ads to a variety of Facebook audiences, which were viewed billions of times.13

Technology helps us grow as a society—it creates demand that was never there. It also makes the world a better place by banishing darkness; providing reliable transportation and communication; and improving our health, prosperity, and understanding of the world (and universe) around us. There are whole new markets, whole new businesses, whole new ways of working, whole new ways of thinking and creating that didn't exist 10 years ago, 5 years ago, last year.

That's the good part.

The bad part, which could threaten all of that, we as marketers, data scientists, engineers, technologists, and innovators need to understand is that the benefits don't always apply to all groups evenly, and the power that technology can engender doesn't flow equitably. If we don't take a step back and set aside some time to think about what it is that we're doing in a structured way, we may create so much distrust that we are unable to manage it. It's come full circle to the point where governments don't understand this well enough, or they understand only pieces of technology and digital, and they try to prescribe answers that may only solve part of the problem or make matters worse.

In my view, the essence of capitalism is to constantly reinvent, constantly creatively destroy, and constantly bring new ways of doing things to the fore. If you use this technology to protect versus to reinvent, then to me that is what ultimately undermines the growth and innovation that we've seen. Maybe the companies that were thought of as the scrappy start-ups have become behemoths. They suddenly realize that they're no longer as innovative as they once were, and they struggled to get back to their roots. You see it at its worst when organizations are anticompetitive, and that's a pervasive danger.

There has been a lot of talk lately about breaking up “Big Tech” companies such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook, asserting that they are monopolies. However, perhaps we shouldn't be too hasty when it comes to trying to tear them apart. While some may see political gain from demonizing these large companies, they aren't necessarily breaking any laws. Says Boston University Questrom School of Business professor, Michael Salinger, “You're only guilty of monopolization if you've attained your monopoly by means other than providing a better product at a better price. Look at Google. People want to search on Google. Their search yields useful information and it's free, so it's no wonder they've got such a strong position in the market.”14

Says Boston University Questrom School of Business assistant professor, Garrett Johnson, “It's frustrating that the conversation tends to go along the lines of, ‘These companies are doing bad things, so we want to hurt them by breaking them up.’ If we start breaking up companies wantonly, that's going to hurt innovation.”15

Is that the best way to improve trust?

There's no single way to solve this particular equation. I think it's going to require new ideas and new thoughts, but first a recognition that there's a potential problem. Even if it hasn't yet occurred in your organization, there's a potential problem. And maybe we need to constantly have some sort of mechanism in place here, whether it's internal to an organization, or unique to an individual entrepreneur, or part of a state-sponsored way of thinking about reinventing what's right and wrong in terms of regulation. Those things need to be addressed and we must be very open about them.

I am often asked, “How can I use technology to be more innovative?” I think that's the wrong question. I think innovation has nothing to do with the technology or the technology platforms you may deploy, and it has everything to do with what kind of community you want to be and how you engage and motivate it. How are you going to attract and retain people who are really creative, and encourage them without stifling them? You don't want to disturb those mechanisms because that could damage your current operation or your current business.

Addressing Institutional Amnesia

If you chart the maturity path of any organization, there's probably a graph that looks very similar, no matter which institution it is. That's because it's a human journey. From someone with an idea to do something different, to address a longstanding problem, to right a wrong—whatever it may be. That person convinces a couple of other people to join them, thereby creating a start-up of some sort. It could be a new nonprofit organization or a new for-profit business that has the potential to grow and to have an impact on the world.

To scale, there are certain paths you need to take—certain controls you need to put into place and certain kinds of people you need to hire. And that maturity path probably looks very similar for every single company, institution, or even government that has ever existed. You can, for example, think of the United States as an interesting start-up with a bunch of somewhat cantankerous founders who had a revolutionary idea. They got together and kicked around their idea over tea and ale, building on it and gaining momentum.

I think what happens when organizations grow—when they go from start-up to being mature, multifaceted, and highly successful—they need to be more efficient and they need to watch their productivity. All good things in and of themselves, but where is the trust factor in this journey? It's often lost in the din of other priorities. I am not asking, “How do you ensure your leaders and employees are trustworthy?” I am asking, “How do you build and maintain the intimate trust of your core constituents, and how do you maintain it in spite of scale?” You do this through improved experiences and the flourishing of empathy at all levels.

As Accenture's report “Shaping the Sustainable Organization” explained, “Sustainable organizations are purpose-led businesses which inspire their people and partners to deliver lasting financial performance, equitable impact, and societal value that earns and retains the trust of all stakeholders.”16 To be sustainable and successful, you have to embed these behaviors and practices into the entire culture. Listen to stakeholders, be empathetic to their experiences, and truly take on their concerns and needs.

But what often gets forgotten is the thing that sparked the organization in the first place. And the spark comes from people. It comes from human ingenuity and creativity. It comes from visceral experiences we have that get us thinking. As organizations travel along the maturity path, at the apex of that curve, they suffer a form of institutional amnesia. They do so at their own peril because, chances are, they'll miss the writing on the wall. They'll miss the greatest opportunities to grow and innovate. They'll shy away from experiencing creative destruction and being reborn.

The organizations that get it right aren't afraid to take that risk. They make the leap when they arrive at the top of the apex of the maturity curve. It might look like they're destroying value, but in truth, they're getting closer to their human roots, the visceral needs that are in all of us. And as a result, they get closer to their customers again because they've had to think about how they do business completely from scratch.

What matters most to you in those moments are the human experiences. Even if you self-help, you find that in the process of doing it, the organization made it very easy for you—intuitive, smooth, and easy. It was empathetic and designed a process that met the needs of the human based on what issues, problems, and stumbling blocks they may be likely to encounter. It's not a question of, “I'm going to get rid of my call center and humans,” it's “I'm just going to make that interaction a lot more valuable for all parties.”

But there's a higher plane of trust: companies that put in place the right culture and behaviors to listen to customers and come up with the right products and services. And increasingly, they have to be bold. They need to think of creating a platform to grow their business. No point selling a furnace, you've got to sell household environmental experiences. No point selling cars, you've got to sell mobility and unique personalized destinations. It takes companies doing something profound—not just improving customer service and love, but having the determination and the courage to reinvent themselves. They recognize that they've got to share value with others in the ecosystem and blur the lines of operations, both within and without the organization.

I don't think of service as a separate function or endpoint, but a lot of organizations with few exceptions still do. They'll have a customer service group, and in my experience, customer service groups have got to be one of the most challenging experiences you could ever have. If you can survive being a customer care representative, you can probably survive anything. All day long, customer care reps are required to deal with people who are having serious issues—and those people are often frustrated, overworked, underappreciated, and even a bit angry about their plight.

That's not all that unusual—they're human. They are each of us and all of us. But in my view, this is one of the most valuable functions an organization can have. Indeed, my alma mater, Bloomberg, made it a core selling point—call their help center and they promise to pick up within two rings and connect you with a real person. They promise to solve your problem first time.

In the twenty-first century, those companies that really succeed will go back to the future. They'll realize that they need to be closer to their customers—not just because they think they know more about them, but because they are truly connected to them. They are part of a community that needs to act and engage like a community.

I think the ideal company of the future is not going to be rigidly segmented into different operational departments such as marketing, sales, service, manufacturing, or development. It's going to be everyone in the company as a marketer, salesperson, customer service agent, everyone having a hand in innovation, and so on. These are the best parts of how start-ups operate—everyone pitches in and learns about the customer and helps build a community of trust.

They should regularly walk a mile in a customer's shoes and really get to know them. Hiding away in some part of the organization and quietly doing their bit is going to be a luxury that no company can afford. They should all be able to tell you what three things they know about their most valuable customer that their competitor doesn't.

If that's the thesis, and if we think that's the way organizations are going to be successful, then everything is going to have to change in the way that information flows, how it's shared, and the intelligence and so-whats that are divined from it. When you do, if your customer has a problem, you can act or change direction faster—before it becomes a larger issue or missed opportunity. Not only in terms of pounds and pence, but it costs you in terms of brand trust. It's always less expensive to hold onto a customer than to get a new one, the same as it is with good employees. And the companies that suffer the most are the ones that do the math and realize that they're churning both. It's a zero-sum game. It erodes value over time.

I have a friend who worked for the chief marketing officer at SAP, which was traditionally a very structured organization. This fellow worked in social media, and it was the first role SAP had ever hired for someone to focus on social media. Social media was very worrisome to the majority of people who worked there because, at the time, there were only maybe two or three people in the entire organization who could speak outside the four walls of SAP about anything—who could talk to the customer extemporaneously. That clearly had to change.

A few years ago, SAP's CMO made a conscious decision that everyone was going to talk to customers and to be as open and transparent as they could possibly be. They realized that it was their job to help their customers—even if it was an esoteric or arcane request on a weird channel that typically wasn't the right channel to go through. That's how we are; humans are leaky buckets and the water is going to find its lowest level and go to wherever it needs to go. So why not recognize that and figure out how to build that intimacy across the entire organization so that everyone in the organization understands the customer?

The Digital Law of Diminishing Returns

I personally believe that the more obsessed you are with becoming “tech- and data-centric, agile, and innovative,” the less successful you will actually be. It's about being smart, not checking the latest boxes someone says you need to check. It's about recognizing that there are a lot of things that you don't know about your most valuable customer that your competitors probably do. Again, there's that question that I never stop asking executives and myself: “What three things can you tell me about your most valuable customer that your competitors don't know?”

What about you? Can you name three things about your most valuable customer that your competitors don't know?

I'll guarantee that it's going to be a hard question for you to answer because we get so into the process, and we get so consumed with acquiring and churning through data, and we get so consumed with developing reports, that we often miss the forest for the trees.

I once traveled to one of Accenture's development centers in India to take a look at what the teams are doing there. It was fascinating—I was amazed at the work that is being done, for every brand you can mention. I talked with someone who was leading a social media team for a particular client, analyzing the performance of campaigns. “That's fascinating,” I said to the team leader, “what exactly are you looking at?”

“We are measuring the impact of digital campaigns,” the team leader said, “for example, the launch or content programs. The client wants to see that their money was well spent. They want to see their CPMs, how far their campaigns traveled, and how people engaged with or shared content.”

“That's great,” I continued. “What are the insights that came out of that? Did they learn about some new product that customers might be interested in, or a feature that they're looking for? Or did they learn that there was a problem that a sizable percentage of customers are dealing with? Or did you drive them to do something, like download a special coupon or sign up for an app or join a community—something tangible?”

“Well, no,” replied the team leader. “The client isn't asking for us to do any of that.”

“What are they asking for?” I wondered out loud.

“They just want an Excel spreadsheet with media reach and frequency,” explained the team leader.

“There's a big, missed opportunity here,” I said. “What if you could take a step back and just pause for a second and ask your client, ‘What three things would you like to know about your most valuable customers or prospects that your competitors don't know? What would that be worth to you, particularly if you could execute against it?’”

Asking this question will help you pick out the most important and actionable targets and avoid getting drowned in a sea of data. Instead of experiencing decreasing returns on digital, your organization's effectiveness will increase exponentially.

Are Institutions Unprepared?

Despite the general belief that the majority of organizations are unprepared to build truly empathetic digital systems, saying that they're all unprepared is clearly not the case. Organizations are prepared in pockets, and the unpreparedness that's out there is mostly for taking the next leap—joining the dots together to build understanding and empathy for customers into the fabric and DNA of organizations.

When I was running social media for organizations, people would ask me, “What's the value of social?” My response was usually something along the lines of, “I think of social as being the solvent for an organization. It loosens up the bonds that you normally have and breaks down or melts the barriers between different parts of the organization—shining a light through the holes that it punches and giving you insights about the customer in real time.”

When social opens up those holes, there should be a customer at the other end—a customer that you maybe never noticed, or engaged with, or learned something about. In fact, that customer might be just a mirror—it might be you.

Everyone who is a customer or a consumer is going to form an opinion about that organization based on the last conversation or interaction they've had with that brand. It's not what the brand tells you it is. It's not an abstract brand promise. It's not whether you were able to fulfill your orders on time or fulfill the price guarantee.

It's about what little thing did customers experience today in the interactions they had—whether online, offline, face-to-face, remote, in an email or chat—that will color their perspectives and perceptions of that brand, and in their own minds decide whether to engage with that brand again? That's the world we live in—that's what the digital solvent has done. You can hire as many agencies as you want to come up with fantastic and creative campaigns, and they can come up with wonderfully humorous or thought-provoking ads. But at the end of the day, it's not about the creative; rather, it's about whether you make a real connection with someone? Did you learn something about them? Did you drive a behavior that otherwise would not have been realized had you not made the effort?

Victoria Morrissey is chief marketing officer at Ferguson Enterprises, and before that served as global marketing and brand leader for Caterpillar. In an interview, she told me about the power of making connections with customers on their terms:

If you use Ferguson as an example, you get a lot more traction if you aren't the one imparting the knowledge, but you're the one enabling the connections.

In my experience, the power of social media lies in uncovering and sharing the amazing customer and associate stories and using those stories and experiences to create a community linking others who are dealing with some of the same things. It was the idea of “it was brought to you by Ferguson or Caterpillar.” It wasn't about the company imparting the knowledge, it was about unleashing the power that comes from connecting customers with others who were in the same boat they were.

They want to learn from each other because those lessons are really, really valuable. And if you connect them, you get credit for building that relationship. The rest is history.

The problem, I imagine, is that in many organizations, leaders are wedded to the past, to the status quo. They don't really know any better. One of the easiest things to embrace is inertia. Think about how hard it for us personally to try a new series on Netflix, though their algorithms do their best to present us with options the company thinks we'll like. It usually takes a lot of people nudging us before we'll try something new. It's much easier to just stick with what we already do and know.

If you're an executive, a CMO, or some other organizational leader, that's not good enough. You've got to be willing to take a risk if you hope to move the organization forward and to scale. The question that often gets in the way is this: Are you going to be willing to bet your career on doing something new? Something a bit daring? Are you willing to become a company that listens to customers and their human needs and creates products and services they really need—as well as deliver them in smarter ways?

Few executives get fired for doing the same thing over and over that has worked in the past. Even if that thing has less and less impact on growing and changing, evolving and innovating, and connecting with your existing and prospective customers. You're not going to get fired. You will (like the organization you work for) more likely fade away. For 100 years, Sears was the top retailer in the country—until they weren't. Amazon and other nimbler competitors ate their lunch.

As I have said often, Sears should have been Amazon—it was the Amazon of its time. There was not a corner on this continent communally glued together by a bigger brand than Sears. They taught us how to shop, and we evolved along with the brand—the company was an integral part of our social fabric and traditions. To then miss the boat on the next big thing—why? This was their DNA, this was who they were, this was how they were built.

You can go through every industry and examine each one and how the top brands are trying to scramble toward a digital world. But here's a cautionary note: in that scramble, don't just do stuff because you think it's important to do, and that you think you're going to be left behind because you didn't embrace technology soon enough or completely enough.

Whatever you do, whatever you've invested, don't lose sight of the most important thing, which is understanding the customer: new ones, old ones, existing ones, potential ones, former ones. That's what is going to drive everything that you do today and in the future—from process, to platform, to channel strategy, to marketing strategy, and on and on. You need to have a thirst for understanding the problems, trials, and travails of your consumers and customers—B2B or B2C—and then be able to empathetically design for people in the context of the ever-changing needs they have. Hold on to them by being a better and more understanding friend than anyone else.

That is how you build and retain trust.

That is how you continue to grow.

Notes

- 1. https://www.businessinsider.com/mad-men-v-reality-compare-don-drapers-ads-with-those-that-actually-ran-in-the-1960s-2012-3#but-this-real-samsonite-ad-from-1964-emphasizes-the-style-of-the-luggage-and-not-the-strength-although-previous-campaigns-had-showcased-the-products-strength-18

- 2. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/texting-isnt-first-new-technology-thought-impair-social-skills-180958091/

- 3. https://www.accenture.com/us-en/blogs/technology-innovation/carrel-billiard-cooperative-experiences

- 4. https://www.mcafee.com/blogs/privacy-identity-protection/key-findings-from-our-survey-on-identity-theft-family-safety-and-home-network-security/

- 5. https://www.slicktext.com/blog/2019/02/survey-consumer-privacy-fears-after-cambridge-analytica/

- 6. https://www.rsa.com/en-us/company/news/the-dark-side-of-customer-data

- 7. https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insights/strategy/generation-purpose

- 8. https://www.forbes.com/sites/andriacheng/2019/06/20/mcdonalds-first-major-acquisition-in-years-could-be-a-game-changer/?sh=22a5c9c2361d

- 9. https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insights/strategy/reimagined-consumer-expectations

- 10. https://www.emarketer.com/content/most-consumers-creeped-out-by-ads-that-follow-them-across-devices

- 11. https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2021-01-13-social-media-manipulation-political-actors-industrial-scale-problem-oxford-report

- 12. https://investor.fb.com/resources/default.aspx

- 13. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/mar/23/leaked-cambridge-analyticas-blueprint-for-trump-victory

- 14. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2019/break-up-big-tech/

- 15. Ibid.

- 16. Ellyn Shook, Peter Lacy, Christie Smith, and Matthew Robinson, “Shaping the Sustainable Organization,” Accenture https://www.accenture.com/us-en/insights/sustainability/sustainable-organization