CHAPTER 12

At the Speed of Relevance

IF THERE IS ONE thing that the history of research and development teaches us, it is that an R&D system cannot be independent of the economic, social, political, and technological environments it operates in. In the United States alone, the country has developed through at least four R&D systems (Mowery and Rosenberg 1989). The first was the pre-World War II system where research and development were undertaken by large manufacturing firms that invested in labs. The federal government's participation in that system was minimal. Post–World War II a different system emerged, which was led by the federal government. The federal government not only financed research and acquired the output but also facilitated the creation of research centers and supported institutions and universities. The third R&D system evolved during the 1980s, which called for significant collaboration between academia, industry, and the government and where international research collaboration increased. The fourth R&D system developed during the Internet revolution and involved opening up R&D to individuals and small firms. Through open source and crowdsourcing, R&D in many areas became democratized. Each one of these systems was marked with its own environmental factors and was in response to the economic, social, political, and technological environments of its time.

Ignoring the environmental factors of the R&D and the related technological transformation leads to inefficiencies in R&D. For example, Britain's inability to deploy an R&D system that was organized from an industrial research perspective is often identified as a reason for low research outcomes during the first half of the twentieth century (Mowery and Rosenberg 1989, 99). This leads us to the second important factor: research outcomes matter. R&D outcomes are also dependent on the times during which they happen. The need of the hour determines what would be considered important and a good return on R&D. The outcomes, therefore, should set the measurement scale by which the performance of R&D will be determined.

The process of R&D must also consider the value chain of research in an industry. For example, the research value chain in health care extends far back into preclinical on one hand and population management on the other hand.

Then there are issues of research related to the approach to research, and that opens discussions about the style of research—for example, originality of research vs. imitation or copying.

Lastly, the nature of competition greatly affects research priorities. The structure of competition itself can be triggered by geopolitical forces or by the nature of competition within a sector, across industries, and globally.

Thus, prioritizing and planning R&D implies determining the nature of the R&D that is consistent with the above factors and is very much dictated by the forces defining your times. Applying an R&D system that is inconsistent with your times or incompatible with the surrounding environmental factors will lead to substandard outcomes and inefficiencies. Approaching R&D as fanning money out to drive innovation without understanding all the environmental factors is a recipe for disaster.

In the past there have been periods where prevailing R&D systems deployed in America were incompatible with the environmental factors (economic, social, political, and technological) and they led to unproductive outcomes (Rosenberg 1994). R&D productivity returned only when adjustments were made to align the R&D system with the environment in which it was operating. One example is when in the 1980s Japanese innovation and focus on speed and quality forced America to reconsider the regimen of federally led R&D, which lacked significant industry participation. Only when America changed the R&D system did the performance of American firms start increasing.

The main question and the need of the hour is to determine what R&D system would be most suitable to compete in the AI revolution. We contend that the environmental factors, competitive rivalry, scientific process, value chain, and the style of research have all changed to a new state of equilibrium. What lags, however, is the prevailing R&D system, which has now become chaotic and is a hodgepodge of various previous R&D systems deployed in the United States. While it reflects the multigenerational features of R&D systems, it is completely incompatible with the environment of the day. And that is having a hugely negative impact on America's productive potential.

WHY THE CRITICAL TONE?

In this book we took a critical view of the American AI policy and implementation. We could have taken a softer, less critical, and more mellow approach. But we feel that would not have been in the best interest of America. There are critical flaws with the current strategy. Many of those are related to the people who are held responsible to make AI successful in America. Others are due to inefficient processes. And yet others due to the unique features of AI. What is consistent, however, is a strange cognitive dissonance where in report after report we are recognizing the failure of American AI, and yet we are continuing to go down the same path that has already cost us our leadership position.

Our journey in the book started by pointing out the ugly truth: America is falling behind in AI, and by some standards the situation appears hopeless. At least that is what Chaillan said when he resigned. Since similar vibes are coming from other sources as well, including the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, they must not be ignored. Some would choose to reject those voices. Others may accept the situation but ignore it. And others may prefer to live in denial. However, we decided to directly confront the problem. We recognize that our approach may feel negative or cynical to some people, but we prefer to be safe than sorry. The nature of competition is such that we cannot ignore these developments.

We also talked to two executives who shared their perspectives about the challenge we face as a nation. Tom Maher, a supply chain professional and senior executive at Dell, with 30 years of experience, shared his concern about China's rapid adoption of AI compared to America's anemic embracing. But he was clear that decoupling makes sense not just because of the geopolitical issues but because it will increase supply chain resiliency. “It makes business sense, and it will happen anyway,” Maher said. “What will really make a difference, and what has helped China propel, is whether we have the data sets or not.” Another executive, Robert Bruck, who was formerly at Intel and now is helping develop supply chain strategy at Applied Materials, talked about the R&D systems in terms of collaboration platforms. He mentioned that many years ago Intel ignored building adoptive coalitions, and that turned out to be a “huge mistake.” That is something that Samsung and TSMC did not do. They both shared information with international partners, and that helped them overcome operational and development problems. Intel has recognized that as a problem and is fixing that. Both executives point to the fact that research and development cannot be divorced from the industrialization and supply chain needs of a firm or a country.

Throughout the book we took a pragmatic approach and analyzed the situation without providing the underlying theory behind the arguments we were making. Here we would like to provide some theoretical basis for our concerns.

UNDERLYING THEORY

We begin by explaining the reason behind our heightened state of concern. Technology adoption is not a straightforward process. As Rosenberg, an economic historian, explains, technologies do not develop in a linear manner (Rosenberg 1994). Information is embedded in new technologies. The process by which information is embedded is of value to determine the development path a technology will take. The trajectory of an innovation is determined by many factors, and technological change is a complex process. However, the key question, Rosenberg argues, is to determine how much information can be extracted from existing bodies of theoretical knowledge. The theoretical knowledge domains are spread over scientific and technological areas, as well as economic, social, political, and technological systems. There are information interdependencies, and that affects the technological change and the direction it takes. Rosenberg argues that such information embedding makes the technological change path dependent, and the initial conditions as well as the prevalent conditions at every step in the evolution of the technological change will nudge the movement and the direction of the change. The catch is that there is a cost associated with finding that information and exploring the information dependencies. Foresight is not free.

Rosenberg clarifies that: (1) new technologies at birth are in primitive form; (2) their development depends on other factors—including complementary technologies; (3) major technological innovations introduce entirely new systems; and (4) technological feasibility alone does not determine its success—what does determine success is identifying human needs in new ways and contexts that have not been done before and in accordance with the new technology.

Based on the above discussion, we argue that the cost-benefit analysis of getting information that can help determine both the direction of the trajectory of technological change and its current state is important. In other words, the direction in which a technological change moves and the future states it can acquire can have economic consequences such that each path-dependent state can represent a certain outcome. Each of those outcomes can be approached from a risk perspective, and cost can be assigned to the risk itself. Extracting more information can be justified if the initial analysis shows that risk and the associated cost can be reduced.

The above also shows why we are so concerned that the initial conditions—what we have termed the anchoring bias—created by the OSTP will continue to determine the direction of the path that the technological change has taken in the United States. The farther we move on this path, the harder it becomes to fix the course.

Technological change does not transpire in isolation. The structure of the economy affects it. This includes the incentive systems, the institutions, and property rights (North 1981, 1990). These factors affect transaction costs, which determine the performance of the markets. Extrapolating the concept and applying it to determine which path-dependent states can reduce the transaction costs, increase adoption, and allow a technology to diffuse faster at a socioeconomic level can help identify the compatibility of the existing socioeconomic structure with the progress outcome expected from the technological change.

Extracting information, therefore, can be a worthy exercise, if it can help determine the path or the trajectory a technological change can take and most importantly if such an information can be useful to influence or nudge the trajectory to better outcomes.

None of the above is compatible with the “fanning out the money and opening research centers” approach taken by the federal government in the current AI technological revolution. The peculiar and uniquely revolutionary dynamics of AI are not being considered. The investment in AI is happening in accordance with the legacy models and systems of R&D. The “build it, and they will come” style of investment ignores the dozens of social, political, economic, and technological constraints pointed out in the book.

But the absence of economic compatibility is not the only problem with how both federal and private R&D investments are being made in AI. The AI revolution has become a transformation for the elitists and a source of fear, concern, and anguish for the rest. Lacking the egalitarian identification of the revolution, it is destined to fail. It is increasing the wealth and power concentration to a point where it is necessarily forcing the masses to accept it without questioning it. In some ways, it is worse. It is creating a system of epistemic oppression where people do not even know the difference between what is hurting their interests and what is helping them. Hence, it should not be surprising that the social and ideological conflict in America is at an all-time high.

Throughout this book we have shown the examples of negligence, of nepotism, and of blatant disregard for facts. We have shown how the OSTP office has not been able to move the needle on the American AI strategy. What is being measured as performance are the activities and not the results. How many dollars are being invested, how many institutions are being opened, how many conferences are being organized, and how many agencies have started AI projects are all measures of activities. They do not exhibit whether the technology is making improvements in productivity and improving the American economy. They also do not show how such performance factors compare to those of the great-power adversary or a competitor such as China. Not only the national AI strategy is fully detached from traditional economic measures, but it does also not consider the unique nature of the AI revolution, which has made many of the traditional economic measures irrelevant. The nature of the competition is at least two generations past than how it is being measured and reported in America. And most importantly, it does not show how American lives are becoming better.

The point is that we need a strategy that truly captures all of the above factors and a real scorecard that makes measurement relevant to the national goals and priorities. In the following discussion we make several recommendations on how to reset the AI launch in America.

RECOMMENDATION 1: MAKE A DISTINCTION BETWEEN NATIONAL AI STRATEGY AND R&D PLAN

As we have pointed out in the book, national strategy should not be confused with the R&D plan. The R&D plan is part of the national strategy but not the other way around. The OSTP and all the other related offices and committees must stop calling their plans national AI strategy because they are not. National strategies do not result from closed-door brainstorming sessions by a few scientists or 46 RFI responses. They also cannot be triggered by a plethora of legislation being directed to jump-start AI in America. These knee-jerk reactions neither create positive results nor are they strategies. Strategy development process is a complicated process that requires applying a rigorous process and understanding both environmental factors and the complex interdependencies that form the basis of the competition. It is important to employ a rigorous planning process to develop the strategy.

In one of our conversations with a senior executive at GSA, we brought up the need for rigorous planning, and she asked an extremely relevant and powerful question. She said, Does this type of rigorous planning that you are suggesting turns into a central planning model [Soviet Union and China style]? The author explained that at an extreme it could, although what is needed is not to go to the extreme but to develop a sensible policy based on facts. The idea is not to control every economic action in the economy but to provide institutional guidance so capital is not wasted and the technological revolution develops under favorable conditions. She agreed with that approach.

RECOMMENDATION 2: DEVELOP A REAL NATIONAL STRATEGY

The American Institute of Artificial Intelligence has done significant pragmatic AI industrialization work for the past six years. The authors recommend that government should conduct and engage in a national strategy development process outside of the OSTP. This process, undertaken as a committee, should include the following members:

- American Institute of Artificial Intelligence: 2 members;

- Top strategy firms: (McKinsey, BCG, Deloitte, Accenture): 2 members each, senior level;

- CEOs or heads of strategy of firms from non-tech sectors (manufacturing, consumer, pharmaceutical, financial, others);

- Supply chain experts (2 experts);

- Economists (4 experts, 2 from economic history with focus on technological revolutions and 2 from applied economics with mathematical models of AI competition);

- Technology experts (2 technology experts, 1 from the AI field);

- Military experts (4 military experts from various branches, could be retired generals);

- Professors and researchers from political science (policy) and sociology.

Note that our committee does not include significant number of members from government agencies (other than military), ethicists or futurists, or AI experts. All of the above members must disclose their financial or other conflicts (companies they have invested in, equity they hold, or funding they have received). This committee should be tasked to develop a national strategy and be funded by the government. The committee may bring in other experts, agency heads, and others on an as-needed basis. The committee is tasked to develop a strategic plan and not just soft policy statements. A strategic plan has specific goals and objectives, is measurable in terms of progress, and has clear timelines. It has a strong execution dimension, and it considers the interdependencies and factor in as many relevant elements as practical. We expect this will be a one-year project.

The plan should be able to provide a mechanism for determining how to allocate research grant for maximizing favorable national outcomes. Favorable national outcomes are not just economic, they are also social and political. Factors such as AI governance and ethics are also considered for achieving favorable national outcomes and not as meaningless boilerplate statements. Ethics and governance are implemented and architected an implementable in the strategic plan.

The plan should also analyze the gaps between where current policy is and where it needs to be. The plan is not a recommendation—but instead a path that needs to be followed to achieve certain results.

The plan will also include a path to evangelize and communicate the strategy, of change management at national level, of getting various stakeholders onboard, and of socializing the plan. This will include a way to talk about the AI at a national level, on how inspire the nation, and how to mobilize the country behind the technology.

Legislation alone cannot accomplish a transformation. You can't legislate your way through a technological revolution. Strings of unsynchronized legislations do not lead to a coordinated national performance. If anything, it confuses people. With dozens of directives and hundreds of instructions, legislations are policy responses and not policy initiators. The plan will highlight the need for various legislative interventions, if necessary.

The focus of the plan will stay on industrialization, the long-term performance of the US economy, and national interests. An “America first” paradigm will drive the plan—and in this case America first does not mean isolationism, it simply means that the interests of the American people will be the sole determinant of strategy, and not factors such as special interest or lobbies. It also means developing an America-centered supply chain.

The plan must possess industrialization maps, including determining the needs of sectors, of developments across sectors, of supply chains, and of foreseeable applications. Efficiencies and the structure of the economy should be considered.

The plan should include a comprehensive analysis of the supply chain changes happening from the geopolitical drivers. In other words, a national AI strategy must corroborate with the geopolitical situation unfolding with China. This means rebuilding American supply chains with AI and building AI with supply chains in mind.

A $1000 monthly AI fund is not what America is all about. The plan must find a way not to turn America into an Elysium city. It is illogical to assume that automation based on data will create massive joblessness. If anything, it should be the opposite. All the new data will point and identify new types of problems that need to be solved. This means humankind will be solving many more problems that affect survival. The goal should be to engage the population, to retrain them, to reskill them, and to inspire them to be part of the revolution. People should not be forgotten and left behind when technological revolutions happen. The focus of retraining should not be on producing data scientists from a handful of schools or retraining federal acquisitions teams or launching competitions. A person who is from central Illinois or rural Georgia should be part of the transformation just as much as someone from Silicon Valley or Boston or New York.

The plan must take into account the political rhetoric and the ideological conflicts in America and include a way to minimize the negative energy and develop greater harmony and unity in the nation.

Finally, and most importantly, the plan will become the basis for both the decoupling strategy to reinvent American supply chains and for rebuilding the American infrastructure.

What America needs is an integrated plan that captures all of the above. Only that plan can be called a national strategy for AI.

SUMMARY OF THE BOOK

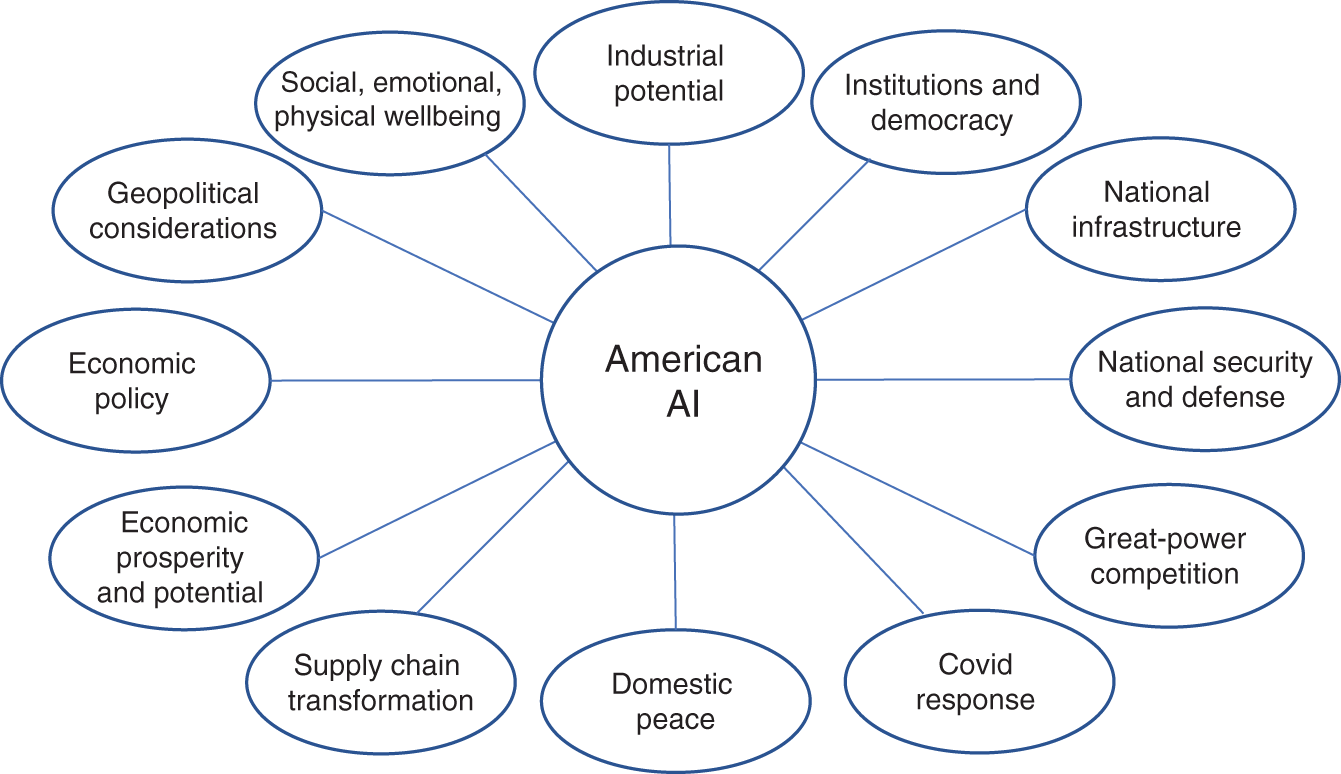

We started by pointing out that the nature of relationships between various drivers of the economy, society, technology, and politics have changed. Now, we argued, all of those factors must be understood in light of the most powerful revolution in the history of human civilization: artificial intelligence. We also argued that almost all of the current problems and their solutions are directly related to AI (Figure 12.1). The ability to identify our problems and discover solutions are now very much dependent on AI.

Hence, AI is not just a technological revolution, it is a comprehensive transformation of the economy, political systems, society, institutions, science, and technologies. A change of that scale should not be managed by half-hearted, politically expedient, or pretentious initiatives. When one considers the competitive environment of the world, the responsibility to get this right becomes even more important. In no uncertain terms, we called it the existential competitive threat to the United States.

Despite the importance to get this right, we have seen a series of actions that have destroyed value, and as a consequence America is losing its competitive advantage. America is sliding, and the AI leadership position is slipping. However, even though this change is happening and even accelerating, there is no awareness to identify the root causes of that decline. There is no appetite to confront the truth. There is no worry about the consequences of such a dramatic shift in competitive power. In fact, the situation is worse. The same exact factors that led to the current decline of America are being now reinforced via legislation and presidential directives. Instead of reflecting on what went wrong, America is doubling down on the exact path that led the country to its current situation. This will only increase the speed of decline. The same actors who were responsible for the decline have seen their powers multiply and their responsibilities increase. There is no accountability, and despite report after report pointing out the decline, the American leadership is following the same course.

We believe the OSTP-led policymaking has created and accelerated the loss of America's leadership position. It is not that OSTP is not doing what it is supposed to do, but it has greatly expanded in areas in which it has no expertise. This includes developing and presenting a so-called national strategy. Not only it is creating a massive confusion, but it has also resulted in a plan which is misleading. An R&D plan is not a national strategy. The constituents and collaborators of the OSTP are not trained to develop strategy. The OSTP has not deployed a formal process that is used to develop strategies of nations, businesses, or military. Most importantly, both branches of the government, executive and legislative, are relying on AI technologists to develop the AI policy. Technologists can advise on the technical aspects of the technology and perhaps on R&D priorities. But they are not trained to develop national strategies. Neither are the ethicists, governance experts, and futurists, the other party that the government is relying upon. What is missing is a practical industrialization plan—a plan that China has successfully deployed.

Surrounded by professors and technologists who are part of a complex and biased network of commercial relationships, the OSTP has architected plans that either cater to the interests of a few universities or Big Tech. To cover the blatant policy failure and biased policymaking, a cadre of ethicists and futurists have been invoked to create an unnecessary distraction. AI's social perception has been framed as the killer robots. This automatically creates a negative perception, which keeps the AI field in the hands of the few. Those who stand at the frontline of the governance and ethics mishaps and disasters can barely keep their ethics boards intact and for the most part pay only lip service to ethics. But the average Joe and Jane on the street are being told that AI is dangerous and there is a need for responsible AI. There is absolutely a need for responsible AI, but since when did we start launching new technological revolutions (or professions) based on their negative aspects? Did we launch auto industry with a focus on drunk driving or the Internet with a concern about sexual exploitation or the cell phone with apprehension about texting and driving or the audit field with the concern about corrupt auditors? It is understood that “responsible” and “ethics” must be a part of anything a society undertakes. But when it comes to AI, it has somehow become a necessary addition to the field as if it were okay to be unethical in other areas but not in AI. All that despite the fact that most ethical violations in AI are happening in firms who appear to be above the law.

In response to the loss to China, America has now initiated several strategic moves on the geopolitical front. These are aimed at retarding or slowing down the Chinese progress or increasing the transaction cost for Chinese businesses. This is directly from the Cold War playbook, and it can be effective to some degree. The other playbook deployed is from America's Japanese experience from the 1980s. While all of those strategies have their place, unless there is a real winning strategy on the domestic front, it is likely that the American situation will not improve.

We are concerned and urge the government to change its course. We ask the government to pay attention to the interdependent environmental factors that are contributing to the decline. Technological revolutions need care, love, and nurturing. They need a positive environment to develop. They need constant monitoring and a sincere leadership. Aspirations should be balanced with pragmatic realities.

America must change its path. We started the book with the powerful concept of “speed of relevance.” That is where we need to be. To win the AI race, America must move forward at the speed of relevance.

REFERENCES

- Mowery, David C., and Rosenberg, Nathan. 1989. Technology and the Pursuit of Economic Growth. Cambridge University Press.

- North, Douglass. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance. Cambridge University Press.

- North, Douglass. 1981. Structure and Change in Economic History. New York: W. W. Norton & CO.

- Rosenberg, Nathan. 1994. Exploring the Black Box: Technology, Economics, and History. Cambridge University Press.