Step 2: Level the Playing Field: Create Guardrails for Behavior

Early in her consulting career, Helen worked with a colleague who she describes as an outstanding leader and manager and as someone with the capacity to be competent, engaging, and empathetic all at once in her client interactions. It was a highly effective mix. Even in tough rooms filled with hard-charging executives, she always found ways to win people over.

The catch? She was the only one among her peers with a four-day workweek. She was adamant about spending that extra day off with her kids, and she rarely wavered when pressured by clients, colleagues, or just her heavy workload. Instead she carefully crafted her schedule to make it all work. She didn't shoulder any fewer assignments than her colleagues and her results were just as good, if not better.

Despite her results, this leader's choice of a nontraditional work schedule came at a cost to her career—a “slower slope,” as she once described it. She insisted the tradeoff was worth it, but Helen could never reconcile the feeling of unfairness. In the end neither the woman, nor Helen, stayed long at the company. Both moved on to better opportunities.

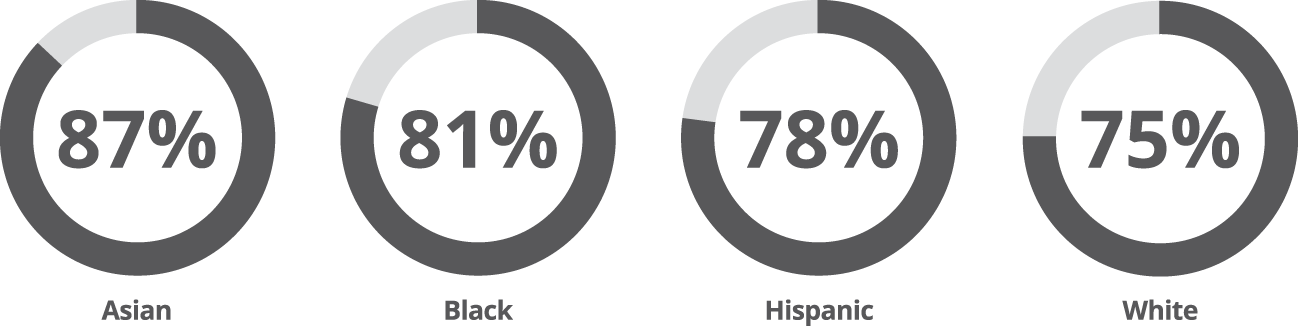

This isn't an unusual story: historically, employees who have flexible arrangements in terms of when or where they work risk being deemed less committed to the organization or not as much of a team player—despite the value they brought to their companies.1 This notion is especially challenging when you consider who is most likely to prefer flexibility. In our survey of knowledge workers across the US, 87% of Asian American respondents, as well as 81% of Black and 78% of Hispanic respondents, prefer flexibility, compared to 75% of their white counterparts (see Figure 2.1).

Source: Future Forum Pulse, 2021. US-only

There are differences among genders, too. 85% of women want flexibility compared to 79% of men (see Figure 2.2).

Source: Future Forum Pulse, 2021. US-only

Working fathers report higher levels of work-life balance (40% higher) and a greater ability to manage work-related stress (61% higher) compared to working mothers.

And it's not just historically-discriminated groups that prefer flexibility in their work. It can be people who don't fit into traditional office cultures, including introverts, or it can be anyone who has ever worked in a satellite office. In 2019, Mike Brevoort, an engineering leader at Slack, made 23 trips between his hometown of Denver, Colorado, and Slack headquarters in San Francisco. No one was requiring Brevoort to fly to San Francisco so often, but he found that if there was a big meeting or executive presentation, he couldn't participate equally if he dialed in. Just about everyone else in those meetings had an office on the executive floor, so he knew they were starting conversations before meetings and continuing them after they ended.

It also just didn't work well to be the only one on screen in a conference room full of people. At the start of a meeting, everyone could see him, but then someone would go to share a document and suddenly his face would be replaced. He described it as being “out of sight, out of mind” because it became difficult to get people's attention or interject with a thought. Then there was the fact that he couldn't read people's facial expressions, hear whispered comments, or banter with colleagues. Brevoort started traveling so often because he knew he had to be there in person to be fully included, and because if he wasn't being seen and heard by the executives in those rooms, he knew it could forestall his career.

It was frustrating (to put it mildly). Frustrating that he had to spend so much time away from his wife and five children. Frustrating that he was losing so much time to the banalities and vagaries of travel. Frustrating that he would barely recover from one trip before he was jumping on a plane for the next. It was tiring and disorienting, and, as it turned out, not entirely necessary—not if the company had just been more intentional about how they enabled flexibility within their organization.

Brevoort first joined Slack when the company acquired his startup. He'd already proven that he could build his own company, so there wasn't much stopping him from doing it again, or from taking his talents elsewhere if his frustrations grew too great. The company stood a real chance of losing him, but the pandemic hit before that could happen and everyone moved to working from home.

Suddenly Brevoort felt like he could get it all done without leaving Denver. When it came to executive meetings or presentations, everyone appeared equally as a face on screen, as they held them via video conference. Most communications outside of meetings—whether about a new product idea or a simple check-in to see how someone was doing—happened in a Slack communications channel. It didn't matter where someone was located because everyone was meeting, coordinating, communicating, and sharing information in the same way, using the same tools. Without his packed travel schedule, Brevoort found that not only was he able to strike a better work-life balance, he was also able to “get more quality work done.” He could do all that because he had real flexibility now that, as he put it, “Slack is our headquarters.”

If companies really want to unlock talent in their organizations, there are much better ways than what the leaders we just described had to go through. And they were leaders, so they had more options in their situations than most employees. In Step 1, we talked about the importance of principles in guiding executive decision-making, but principles set at the executive level are not enough: You also need guardrails to make sure those principles can be translated throughout your organization in ways that are effective and keep the playing field level so you can get the best out of all your people.

What Are Guardrails?

Guardrails are just what they sound like: they're the protective railings that keep you from veering off course. They create the framework in which your flexible work principles can live and thrive by providing a guard against the kind of double standards across employee groups that so many have experienced. They also guard against what we call faux flexibility, which describes policies that appear to be flexible, but still don't give people the freedom and autonomy they are asking for and need in order to make their lives better (i.e. you have the flexibility to WFH, but only one day a week and you still need be available from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m.). Or, the term can describe behaviors that run counter to flexibility (i.e. executives who still come back into the office full-time, five days a week, which can implicitly signal that to really succeed, people would need to abandon flexible options).

Think of it this way: If your purpose is to unlock the power of talent in your organization, then guardrails are there to ensure that actually happens. Because if you're not intentional about how you implement flexible work, you could end up having the opposite effect—creating a greater opportunity- and growth-divide between those who choose more flexibility and those who don't, similar to the “slower slope” career that Helen's colleague described. Research from Nicholas Bloom at Stanford in 2014 showed that, in one company, people working from home had lower promotion rates than their in-office counterparts—a full 50% lower—despite being as or more productive.2 It's not clear from the study if the company was aware of the risk of uneven experiences, or if they did anything to avoid it. But it's still a potential pitfall to be aware of, and one you can actively manage against. We have seen similar issues ourselves, and you probably have too: People who vary from the standard in-office, all-day work arrangement can suffer penalties, often ones they don't deserve. By being intentional about not just what flexible work means to your organization (that purpose and those principles you just created), but how you implement it, executives ensure that flexible work models are actually respected and adopted within the organization—and that they have the intended effect of unlocking talent rather than suppressing it. Otherwise you risk creating inequitable access to opportunities, knowledge, and connection for your more distributed or remote employees.

To help you create effective guardrails, we're going to look now at three main areas where they're most needed and talk about the impact they can make on the employee experience. The three types of guardrails that we'll cover are:

- Leadership guardrails

- Workplace guardrails

- Culture guardrails

Leadership Guardrails

Flexible work is like just about anything else that's integral to your company's success: To make it work, leaders have to set the tone from the top. Without leadership modeling the right behaviors, the principles will fail. What follows are ways that leaders can help ensure their organization lives by their flexible work principles.

Lead by Example

An executive in a real estate firm once described to us how, during an important meeting, most participants dialed in, but all the senior executives could clearly be seen on one tile, indicating that they were together in the boardroom. They assumed no one would notice, but everyone did. It sent a signal that the office was where people needed to be, even though that wasn't their intention. The company wanted to promote flexibility, but the behavior of their leaders undermined the concept. This is an example of failing to lead by example.

Leading by example is a concept you have surely heard before because it's simply good practice in any circumstance. When it comes to flexible work specifically, leading by example means that if you, as a leader, are still coming into the office on a typical 9-to-5 schedule every day, then you're sabotaging the strategy and undermining its principles (even if you don't mean to). No matter what you say, no matter what your official policy states, if employees see you in the office regularly, they will believe they need to do the same if they want access to growth and opportunities.

At Australia-originated software company, Atlassian, leading by example meant “stricter rules” for the executive team. Chief Operating Officer, Anu Bharadwaj, explains: “Even after it was deemed safe to return to the office, we decided executives would not go in for more than one day each week and would not hold in-person meetings, without our extended teams, more than once a quarter, with the exception of social events.” Slack did something similar when adopting what we call our “executive speed limits.” CEO, Stewart Butterfield, went around the room and asked each of his direct reports what commitments they would make to set an example. One that emerged was everyone committing to leaders to spending three days a week or fewer in the office. There was further guidance on how that limited time should be spent: on team events and customer interactions. In other words, the office is for those things that really require people to be present. That was the message Butterfield wanted leaders to communicate through their actions.

Take Symbolic Actions

A great way to lead by example is to take symbolic actions. Find ways to highlight flexible work across your organization. They can be simple actions, like when all executive team members at Telstra, Australia's leading telecommunications company, changed their public profile pictures to show them working from home.3 Or they can send a broader message. At IBM, CEO Arvind Krishna, shared the IBM “Work From Home Pledge” early in the pandemic—not just to the organization, but on social media for all the world to see. The Pledge grew out of the experience an IBM consultant was having as she tried to balance working from home with having a 10-month-old baby who couldn't go to daycare. One day her baby fell just before she had to get on a video call. Her child was okay, but her team could tell she was flustered with everything she had to manage. That got them talking about their new work situation and the new set of needs that came with it. They started challenging the usual norms of doing business and asking questions like, “If we're working from home, do we really have to be camera ready for every meeting?”

That conversation resulted in the team coming up with a list of new norms for the work-from-home, lockdown era. (See sidebar on the following page for the list.) They started sharing the list with others, and word about it spread quickly. Within about a week it came to the attention of senior leadership, and that's when Krishna put it out on social media, to signal his support. This was early in the pandemic, when the company was navigating the sudden switch to working remotely for nearly all of their more than 250,000 employees. Since then, IBM has broadened its definition of flexible work to well beyond just working from home, encompassing schedule flexibility and hybrid (sometimes in, sometimes out of office) arrangements. As a result, team members are working on a new pledge to support their new style of work.

Show Vulnerability

That example highlights another way leaders can reinforce their flexible work principles: by showing vulnerability. Change can be uncomfortable, and it can make people feel like they're on shaky ground. In those early days of the pandemic, Chief Human Resources Officer, Nickle LaMoreaux, remembers Krishna saying often to their leadership team: “Remember, every day you are now being invited into somebody's home. It's important to act as guests with the kind of courtesy that's expected from them.” It was a great way to frame the sort of attitude leaders can bring to everyday situations to normalize flexibility and help people feel more comfortable with it. You can do this by saying hi to the kid who accidentally interrupts a video call—or, better yet, by bringing your own family on to wave a quick hello. When taking time in your flexible schedule for an exercise class or to see your daughter's school play, let people know not just when you will be unavailable, but why. Spell it out in your status message—spending time with mom for her birthday!—or however you communicate with your team.

Slack's then Chief Marketing Officer, Julie Liegl, brought her kids—just eight and five years old—into one of the first company-wide meetings during the pandemic, and the gesture communicated to the more than 2,000 people attending via video conference that she was a real human being who was juggling things too. Feedback was immediately positive. As Senior Customer Success Manager, Christine McHone, said, “When Julie Liegl's daughters climbed on her lap during a company all-hands meeting, it set the tone for the support we'd receive.”

Workplace Guardrails

A successful flexible work strategy requires leaders to redesign the role of the workplace. What that looks like exactly will depend on the needs of your organizations, but doing so effectively will require you to be intentional about setting guardrails to keep people from reverting back to old habits. The following are some examples of guardrails that have been effective in helping to set the tone across different kinds of businesses, which will get you thinking about how to set your own.

Shared Space Is for Teamwork First

In our Digital-First culture at Slack, showing up to the office is no longer the default; it's the exception. As our CEO Stewart Butterfield explained, “Getting teams together in person should have a purpose, such as team building, project kick offs and other events that are planned in advance, pairing flexibility with predictability.”4 Being intentional about the role of the office in this way creates a more structured view of what flexible work can be.

We also got rid of the “executive floor.” Before moving to a Digital-First strategy, Slack's corporate headquarters in San Francisco had a tenth floor that was tricked out with a large boardroom and executive briefing center and a ninth floor C-suite where the CEO and other executives had offices. If there was an important meeting happening at Slack, it was always on one of those two floors. They were known as the place to hang out to show you were around. To get people to think differently about the use of office space, we dismantled that and don't believe there will ever again be a need for an executive floor. Per our new guardrails, when leaders are in the office, they'll most likely be there to meet with their teams. For other interactions, as Brevoort said, “Slack is our headquarters.”

It's likely that you, too, will need to redesign the way you use your office space (a concept we will talk more about in Step 5). Instead of plans for cubicles and corner offices, companies like MillerKnoll have focused on thoughtfully designed social commons that foster collaboration and connection. There may be more emphasis on creating zones for different kinds of work—quiet floors for concentrated work, for example, paired with social floors for team gatherings. If your “workplace” is no longer a building, that opens up a whole range of new possibilities for how you use your physical space.

Keep a Level Playing Field

In order to level the playing field, leaders need to drive a consistent experience and avoid “in-person favoritism.” Outside of intentional time together, meetings should be structured to enable remote participants to be equally present and part of the discussion. To ensure that was happening at Slack, we adopted the guardrail of “one dials in, all dial in,” meaning that either everyone gets together in a room for a meeting or everyone participates remotely, even if that means logging on to a video conference from a desk in the office.

Guardrails like this one aren't always easy to make work, especially when they go against ingrained habits. It took quite a bit of experimentation and practice to get this right (a process we'll tell you more about in Step 4), and ensure that executives were modeling the behavior. For example, by holding product review meetings where everyone dials in (and, in fact, there's not even a conference room booked), the pressure to come in to “the room where it happens” is lowered, and the playing field is leveled for employees who get the opportunity to present to an executive only a few times in a year.

It's also important to think about the variety of methods you can use to encourage participation. Not everything requires a calendared meeting via video conference, which can disadvantage some groups, like those in different time zones, parents who are wrangling kids, or introverts who are unlikely to speak up on a crowded video chat. Don't get us wrong: video conferencing is a great tool, one that has been a lifeline for so many, but it's not the only tool you have. Sometimes communications platforms, chat, voice, and even asynchronous video—pre-recorded videos that people can watch on their own schedules—can work even better. There are a wide variety of tools out there for things like virtual whiteboarding, asynchronous brainstorming, or collaborating virtually on written documents. Be conscious of which tools you use and don't just default to yet another meeting that crowds people's schedules (more on this later in the step).

Rethink the Role of Offsites

Instead of just focusing on which days of the week people should come into the office—which is the approach many companies have taken—companies should be thinking about enabling teams to organize regular events that meet their own needs for team-building and productivity. That will likely mean equipping team leaders with new insights and tools to help them do this.

For example, in a flexible model where team members are working from different places and at different times, people need to be given sufficient advance notice of events. Team leaders also need to be intentional about how their offsites are run. Priya Parker writes convincingly on this subject in her book, The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters: “Gatherings crackle and flourish when real thought goes into them, when (often invisible) structure is baked into them, and when a host has the curiosity, willingness, and generosity of spirit to try.”6 Leaders can answer four key questions to make sure they are being intentional about making their gatherings effective:

- How can I be sure attendees will be comfortable and motivated?

- What's the topic and what do we need to achieve and produce?

- Who will facilitate the event and how?

- What tools will we need?

Executives need to think about how they can support team leaders in creating more effective gatherings, ones that are not only productive, but foster a sense of belonging. In the past, many companies have focused on in-office perks like free meals, coffee bars, or massages to do this, but those things won't work for a flexible, distributed team. Instead leaders need to give people better tools for both in-person and digital “offsites,” like team-level budgets for events, as well as a menu of options (pre-approved items like food and swag and pre-approved vendors to provide them), they can easily pick from. Leaders also need to provide people to support these kinds of efforts, like facilitators who can help team leaders conceive of and plan the right sort of gatherings to meet their needs.

Culture Guardrails

A flexible work culture is going to be different than an in-office one, naturally. But more than that, creating a new flexible work strategy provides companies with the opportunity to address some challenges that have long been part of traditional workplace cultures. We address three big ones here, but there will likely be more that come up as you tailor your strategy to the needs of your business.

Move beyond Meeting-driven Culture

It's a ubiquitous complaint in corporate culture: practically everyone is overwhelmed by meetings. And there are real questions about whether meetings are necessary to get things done, or if they are getting in our way far too often. In a survey of managers across a wide range of industries, researchers Leslie Perlow, Constance Hadley, and Eunice Eun found that more than 70% of people believed meetings were unproductive and inefficient, and 65% said meetings keep them from completing their work.7

It's time to rethink the meeting. At Slack our executives led by example on this by declaring “calendar bankruptcy.” They removed all recurring meetings and one-on-ones from their calendars so that they could consider each one and add back only what was truly necessary. In a message sent out to the entire company, the purpose was explained this way:

- “We're in a new distributed world and gotta change the way we work!”

- “There are lots of legacy meetings that have changed owner, purpose, scope—let's start with a blank slate to determine what's really important!”

This doesn't mean there were no more meetings. It just means that leaders got a lot more intentional about the time they were taking up on people's calendars. We found that so many meetings could be eliminated or broken up into parts. For example, your monthly sales meeting might start with a status update. Why not send that out beforehand? Presentations can be shared as decks or asynchronous video so people can review them in their own time. Tactics like these can lessen your meeting time considerably, and then time together can be more meaningfully spent on meaty discussions or team building. For this to happen, however, leaders have to be more intentional about meetings and employ some forethought and planning. As Priya Parker wrote in The Art of the Gathering, “90% of what makes a gathering successful is put in place beforehand.”

Dropbox uses what they call their “3D” model for planning meetings: debate, discuss, decide. We would add a fourth D for “develop”—time spent focused on honing individual skills or other professional development opportunities. If a meeting doesn't achieve at least one of those four objectives, then it doesn't need to be a meeting. (See our “Do We Need a Meeting?” tool in the toolkit at the back of this book for more on this.) Other tools can be used to disseminate information or get a status check, freeing up much more time in your schedule, and the schedules of your team members, to do the kind of work that really moves things forward.

Guardrails can also be put in place to counter the assumption that people need to be available eight hours a day, five days a week for meetings. Tactics that we've seen work include Levi Strauss & Co.'s “No Meetings Fridays,” which aims to reduce internal meeting load and provide a day dedicated to focus time. Google adopted “No Meeting Weeks” years ago for some teams, and similarly Salesforce has adopted “Async Weeks” as a way to not only give people a respite, but also get meeting owners to think about whether each meeting is needed or could be cut in terms of frequency, attendance, or both. Slack's Product, Design and Engineering team has “Maker Weeks” and “Maker Hours”—two-hour blocks, three days a week, where people can turn off notifications and do focused work. (This is a great area to make use of some of the experiment-and-learn tactics we'll cover in Step 4 to see what works for your organization.)

Challenge the Role of the Brainstorm

One of the common concerns about flexible work is that it will stifle creativity and innovation. After all, how can we come up with new ideas and solve tricky problems unless we gather together in a room and hash it out on a whiteboard? People often have trouble imagining other ways because they simply haven't tried them. And in fact, there's good evidence to suggest that they should. Numerous studies show that the often lauded brainstorming session is a waste of time, at best; at worst it can lead to the dreaded groupthink and even harm productivity.

So-called “brainwriting” has been shown to be a better way to generate new ideas, and it requires a kind of hybrid approach that flexible work is particularly well suited for. In fact, the best known way for groups of people to generate new ideas is to work individually before working together.

Brainwriting starts with individual work, allowing time and space for people to think deeply and freely about ideas without fear of judgment or the influence of louder or more senior voices in the room. You ask everyone to commit their ideas to paper, and only then are they shared and debated—an approach that has been shown to elicit better results. According to the Harvard Business Review: “A meta-analytic review of over 800 teams indicated that individuals are more likely to generate a higher number of original ideas when they don't interact with others.” By contrast, the old way of brainstorming “is particularly likely to harm productivity in large teams, when teams are closely supervised, and when performance is oral rather than written.”8, 9

One of the reasons the brainwriting approach works so well is because it gets more people involved. By allowing ideas to be generated ahead of review, you help create psychological safety for diverse teams and involve more voices that might normally go unheard in rooms where senior and more extroverted voices tend to dominate. It also helps guard against remote workers becoming alienated from such processes. Remember that one of the main reasons that Mike Brevoort ended up traveling to headquarters more than 20 times in a year was because he didn't feel like he could fully participate if he dialed in from Denver. He was able to find a solution, albeit a highly imperfect one, in traveling back and forth, but a lot of employees won't have that option or may feel less comfortable contributing ideas in a large meeting or brainstorming format. It's worth thinking about how much insight, creativity, and expertise you are missing out on by making it harder for all people to participate.

Challenge Your Own Thinking

Practically all of us have “grown up” professionally in a 9-to-5 culture, and inherent in that culture are ways of thinking that we may never have examined very closely. Sheela remembers early in her career working until the wee hours of the morning and being lauded for her “selfless” and “relentless” behavior as a result. Some of the most memorable advice she got in business school was to “burn the candle at both ends until you're in your forties and then reacquaint yourself with your friends and family.”

“No pain, no gain” had always been Helen's family motto until she ended up burning out while still in her twenties from a job that entailed 100-hour workweeks, frequent travel, and a long commute. During a discussion about work-life balance with a partner in her firm, the woman casually mentioned that her personal goal was to see her kids twice a week—not day, but week.

Brian was taught early on that an attitude of “seldom wrong, never in doubt” was key to success, meaning few around him willingly admitted when there were gaps in their knowledge or they didn't have all the answers. This approach proved to be a real liability at his first startup, where there was a whole lot he didn't know—that, in fact, no one knew. He had to get past that ingrained way of thinking fast in order to enlist the help of others in finding solutions to complex issues—otherwise the venture could have failed.

We're hardly anomalies in the corporate world. So many of us have internalized lessons over the years that we've had to unlearn for the sake of our own success as well as that of the businesses we work for. It's time to challenge some of our old notions about what makes someone good at what they do. Like, working more = working better. Or, employees can't be trusted to get stuff done on their own. These are default ways of thinking in most corporate cultures, but what makes us so sure they're right? After all, have we ever really tested them?

In fact, there's lots of evidence to suggest that they aren't right. Evidence showing that stress and burnout make us worse at what we do, not better. That lack of trust demotivates employees rather than motivating them. If we really want to unlock the potential in people, then we need to keep our eyes trained on what really delivers results and stop rewarding behaviors that undermine them. Think about that the next time you praise someone for answering emails late at night or being in the office first thing in the morning before anyone else. Because it's the quality of work and the results it drives that matter most, not when or where you do it.

Why Guardrails Really Matter

Since the adoption of Levi Strauss & Co.'s flexible work strategy, Chief Human Resources Officer, Tracy Layney, goes into the office two-to-three days a week on average, and the week we talked to her was no different. On Tuesday she had a houseguest, so it was helpful to be in the office with fewer distractions. She got up in the morning, did the typical rush-hour commute, and stayed all day. It was like the old days again, except she was mostly by herself, connecting with her geographically dispersed team members remotely. Then, the next day, she took a couple of calls from home in the morning before taking a break to get some exercise. She later drove to the office and resumed work around 11:00 a.m. She stayed into the evening so she could attend a colleague's work anniversary celebration. It was a long day, but one that benefited from off-hour commutes each way. The day after that, she worked from home and knocked off around 3:00 p.m. so she could make her son's cross-country meet.

All three days looked very different in terms of both where she worked and when, and that flexibility allowed her to balance personal needs—for exercise, family connection, less time lost in Bay Area traffic—with professional ones. She still got plenty of work done, but more efficiently and with less stress than if she'd had to compartmentalize her day. Because let's face it: this is just how life is. One day is rarely the same as the next. There are always personal and professional needs that we have to balance. Flexible work simply allowed Layney to better accommodate that reality.

Some version of this flexibility would benefit so many people. The needs of each individual will be different, of course. Instead of a child, someone might be caring for an elderly parent; instead of getting some exercise, someone might have other physical or mental health needs to attend to. Religious holidays, different geographic locations, and even the fact that some people work more productively at night because they simply aren't morning people—all these things and more, really aren't all that difficult to accommodate if we can allow ourselves to think differently about work. We leave behind, or leave out entirely, so many when we can only imagine one way of working: nine-to-five (or six or eight), five (or more) days a week.

What's more, flexibility disproportionately benefits historically discriminated groups and caregivers—the groups most often left behind at work. Not enabling flexibility is a loss, not just for them, but also for our corporate communities and our bottom lines. Study after study shows that diverse teams outperform their peers. They grow faster, are more innovative, and adapt faster to external and internal events. Flexible work enables this kind of diversity. “I think the greatest opportunity is, of course, pipelines,” explained Professor Tsedal Neeley, author of Remote Work Revolution. “Pipelines are getting expanded in extraordinary ways… . You now can hire people from other parts of the country without asking them to move.” Why is that important? It gives you a more diverse talent pool to choose from, and it benefits all types of people, especially underrepresented minorities. As she explained, “You can hire someone without having them extracted from their communities … They can stay where they are and work for you, which is hugely important when it comes to retention and job satisfaction.”10 And the tortured efforts many business leaders have had to make in past years to retain key employees can feel unnecessary when you consider them through the lens of flexibility.

Take Harold Jackson, for example. Just about every executive we know has a story about losing a great employee or jumping through hoops to try to keep one because the person needed or wanted more schedule flexibility, location flexibility, or both. Jackson was one such example for Sheela, who interviewed dozens of candidates for the position of head of analyst relations at Slack, none of whom measured up to him. But Jackson lived in Kentucky, where his family lived, so hiring him meant he had to relocate to California.

Initially Jackson came on his own, leaving his family behind and commuting home on weekends. Eventually his family followed, but they didn't stay long. They didn't like the Bay Area and returned to Kentucky. Jackson wanted to move back too, but Sheela admits she was hesitant at first. Slack was only a few years old and was in a stage of high-growth, so her mentality was that work gets done in the office. She agreed to try to work something out for Jackson's sake, but the company didn't have the infrastructure to make it work. She tried and tried to find a solution, during which time Jackson continued to commute back and forth and then eventually moved to New York, where Slack already had an office, so he could at least be in the same time zone as his family. Finally, after more than two years, it finally happened: Jackson got to move home just as the pandemic hit and we all started working flexibly anyway.

Since then, Jackson has been promoted several times and the impact of his work shines through the company. The effort it took to give Harold flexibility was not a good use of time and energy, especially for something we all adjusted to quite quickly when the pandemic forced our hands. A really important thing to understand about the kind of guardrails we've talked about in this chapter is that they're so often things that companies—most of them anyway—have needed to redesign for some time. As Tracy Layney put it, when it comes to flexible work, “there is stuff we have to guard against, like being biased against different groups, certain people not being visible enough, too many meetings, and overloading people until they burn out. There are real things we have to be careful about, but these things existed anyway.” The shift to flexible work presents an opportunity to address some of these long-standing barriers and drains on productivity in a more comprehensive way.

We will continue with this in Step 3, when we talk about translating your principles and guardrails for ensuring equitable practices into team level norms. The first two steps have been largely about setting the tone from the top in order to create boundaries and expectations for team leaders to follow. Next we will empower teams to create their own practices that best suit their individual flexible work needs.

Notes

- 1. Cohen, J. R. and Single, L. E. (2001). ‘An examination of the perceived impact of flexible work arrangements on professional opportunities in public accounting’, Journal of Business Ethics. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010767521662 (Accessed: 30 November 2021).

- 2. Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. and Davis, S. J. (2021). ‘Don't force people to come back to the office full time’, Harvard Business Review, 24 August. Available at: https://hbr.org/2021/08/I-force-people-to-come-back-to-the-office-full-time (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 3. Telstra ‘Our leadership team’. Available at: https://www.telstra.com.au/aboutus/our-company/present/leadership-team (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 4. Jones, S. (2021). ‘Slack is telling execs to limit their office days to 3 a week to encourage other staff to work from home’, Business Insider, 29 September. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/slack-executives-come-into-office-less-set-remote-work-example-2021-9 (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 5. Sarasohn, E. (2021). ‘The great executive-employee disconnect’, Future Forum, 5 October. Available at: https://futureforum.com/2021/10/05/the-great-executive-employee-disconnect/ (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 6. Parker, P. (2020). The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters. New York: Penguin Publishing Group.

- 7. Perlow, L. A., Hadley, C. N. and Eun, E. (2017). ‘Stop the meeting madness’, Harvard Business Review, July–August. Available at: https://hbr.org/2017/07/stop-the-meeting-madness (Accessed: 18 November 2021).

- 8. Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2015). ‘Why group brainstorming is a waste of time’, Harvard Business Review, 25 March. Available at: https://hbr.org/2015/03/why-group-brainstorming-is-a-waste-of-time (Accessed: 21 November 2021).

- 9. Mullen, B., Johnson, C. and Salas, E. (1991). ‘Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: A meta-analytic integration’, Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 12. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1207/s15324834basp1201_1?journalCode=hbas20 (Accessed: 21 November 2021).

- 10. Stanford VMware Women's Leadership Innovation Lab (2021). ‘Fostering inclusive workplaces: The remote work revolution’, 12 October.