2

Misconceptions that hold us back from investing

It was a cold autumn day on 30 October 1928. Walter Thornton, a 25‐year‐old investor and model from New York City, parked his car, a yellow Chrysler Imperial 75 Roadster, at the side of a busy road.

He exited the vehicle and perched a cardboard sign on the windscreen. The car was worth a pretty penny at US$1555 (about US$25,000 today). The sign read:

$100 Will Buy this Car. Must Have Cash. Lost All on the Stock Market.

Walter stood next to the car and a small crowd of men in slacks, blazers and brimmed hats looked at his offer in pity. A nearby photographer snapped a photo of this moment in time. A photo that later became famous for commemorating this moment. What had gone wrong?

Source: © Science History Images / Alamy Stock Photo

Six days prior, on 24 October 1929, the US saw the Great Wall Street stock market crash, the largest crash the market had ever faced at the time. That day, later coined Black Tuesday, the entire market dropped 11 per cent. The crash signalled the beginning of the Great Depression, which affected not only the US but also all Western industrialised countries.

Many people view the iconic photograph of Walter, the man who ‘lost all on the stock market’, as a reminder of how risky the stock market is, using it to confirm that it's too scary and volatile to get into. After all, no‐one wants to be desperate enough to put up their car for sale for a fraction of its price.

What many people don't realise is that eventually the market recovered, including Walter's losses. You see, in the stock market you don't actually ‘lose’ your money until you pull out your investments. If you have $10 000 in the market in 100 stocks and the market value of your portfolio dropped to $100, you still have those 100 stocks — they're just valued less until the market rises back up again.

That's what happened to our friend Walter. When the market began to rebound he recouped his losses and then some. In fact, he used his wealth to start a modelling agency only a year later. You see, you don't lose money in the stock market unless you sell your shares for less than what you paid for them — Walter must have held on and got the benefits of the rebound. His agency ended up being so successful it became one of the ‘big three’ modelling agencies in the US, notable for its World War II–era pin‐up girls. No‐one seems to remember that part of Walter's story. (As for why he had been so desperate for cash that he had to sell his car that day, that's been lost to history … )

There were other myths circulating around Black Tuesday, including the harrowing rumours that investors were jumping out of windows after seeing their losses and not wanting to face their families. However, research into suicide rates in the US proved no such thing — in fact, suicide rates were lower during that period. It was purely fear‐mongering.

One of the biggest things that keeps investors in training from getting started is not their lack of knowledge, but the perpetuation of misinformation. And there sure is some misinformation out there. All it takes is one question about stocks at any family BBQ or work meeting to hear a range of false information about what the stock market is and why you should avoid it.

It seems like every Tom, Dick and Harry has an opinion on what it means to invest, and if you've been brave enough to ask the question, you've probably heard it all:

Investing is just gambling.

Investing is a con.

Only the rich make money, it's rigged.

Or my favourite,

My uncle's friend's son lost all his money in stocks; avoid it at all costs.

At face value, why would we question these statements? After all, if we don't know much about investing, we might be more likely to trust the opinions of those around us.

Unfortunately, many of these statements, though well meaning, come from the misunderstandings that surround the world of investing. No‐one wants to see their family or friend lose money, so if they fear the stock market, of course they will very passionately tell you why you should stay away. However, it's important to be able to separate fact from myth.

An investor in training listens to these myths and chooses to do their own research to understand what to take on and what to avoid.

This chapter will break down the most common myths about the stock market so that you are well equipped to focus on how to invest, instead of wasting time worrying about what could go wrong. These myths are the following:

- you'll lose all your money investing in the stock market

- investing is like gambling

- investing is complicated

- you need a lot of money to get started

- real estate investing is less risky.

Investors in training know that if you invest with the right strategy, it can be harder to ‘lose it all’. Knowing the best and worst case scenarios puts an investor in training's mind at ease, and allows them to instead dedicate their time to doing what is important: setting up investments for the long term and being able to sleep easy at night knowing they're aligned with their values and goals.

Let's break down these myths.

Myth #1: You'll lose all your money investing in the stock market

This is the biggest stock market myth. If you've been scared off by it, you're not alone; even the most experienced investors wondered about this before they began, and it was a concern I had myself. After all, you work hard every day in your job or business — do you really want to risk losing all that hard‐earned money?

You'd never light $100 on fire, so why risk it with the stock market?

Investors in training realise that people don't just throw their money into the stock market and cross their fingers hoping to make a gain. There are strategies, methods and hundreds of years of research that direct an investor's decision‐making.

Firstly, there are different levels of risk in the stock market, and this can be both mitigated and matched up to someone's risk levels. (At the end of the book there is a quiz to work out your personal risk profile.) One investment can have a completely different risk profile to another; someone purchasing a Tesla stock would be after a much riskier investment, with the possibility of a higher reward, than another investor who purchases a Coca‐Cola stock, a long‐standing and stable brand, which, theoretically, encompasses less risk.

Secondly, it's important to discuss how people lose money in the stock market. The next time you hear someone recall how their friend of a friend lost all their fortune in the market, try asking them these three questions:

- What did they invest in? Did they choose a few risky growth stocks after a ‘hot tip’ that these unheard‐of companies were about to take off? Or did they invest in a broad market index fund that diversifies their risk across hundreds of companies and sectors, so that if one sector dropped, another could rise and balance out their investment?

- What did they do when they saw their share portfolio drop? Did they let their emotions take over and decide to panic‐sell all their stocks into cash, thus solidifying their losses and not allowing their investments to gain back value once the market recovered? Or did they listen to the advice of their financial adviser and ‘hold the course’ and not sell their investments? During the GFC, many financial advisers had to beg their clients, even those who were to all intents and purposes intelligent and otherwise well adjusted, to not sell their positions during the dip. Still, many people sold. Those who held ended up not only recouping their money but making a great return in the years following.

- What do they have to say about the fact that the S&P 500, the index fund that encompasses the largest 500 companies in the US, has, since its inception, never had a crash that it didn't recover from? If anyone left their money in a fund like that for a minimum of 15 years, so far in history, it was virtually impossible for them to have made a loss.

The questions are a bit harsh but they serve a purpose: to reduce misinformation as soon as it occurs.

The investor in training is aware that the main indexes (which is just a jargon word for ‘list’ — I'll explain them in more detail in chapter 5), like the top 200 companies in Australia (The Australian Securities Exchange 200, or ASX 200) or top 100 companies in London (The Financial Times Stock Exchange 100, or FTSE 100), have recovered from every crash they've endured.

In fact, let's go through all the major crashes in the history of the stock market to see exactly what investors mean when they say ‘the market has always recovered’.

The market has always recovered? You heard me right; in fact, I'll share with you the graph that changed my life (figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: the last 40 years of the S&P 500

Source: Based on data from S&P 500 Index — 90 Year Historical Chart. Macrotrends LLC.

This graph shows the movement of the US stock market; it's the S&P 500 index (made up of the top 500 companies in the US at any given time, also known as a broad market index fund) over the last 40 years. See how the market goes up and down in the short term but in the long term has a trend upwards? Despite every single crash, whether it be the global financial crisis or the more recent COVID‐19 crash, the market has always bounced back.

Let's dive into the biggest crashes in history and what we learnt from the mistakes of others.

The 1929 Wall Street Crash

The crash in September to October 1929 was when our good friend Walter tried to sell his yellow car. On 24 October, the market dropped 11 per cent. At the time, it was the largest crash the US stock market had ever seen. Its effects shocked seasoned investors as it came after a period of a booming economy with great levels of production, and it led to what's now known as the Great Depression. Unfortunately, prior to the crash, the market in the mid to late 1920s was being driven by speculation rather than principle. People were mortgaging their homes to pull out cash and pour it into the stock market, as they didn't think the stock market could ever dip down.

The process of using borrowed money to invest is called ‘margin investing’. Investors in training now know that using margin investing to invest in companies, especially ones without intrinsic value, is a recipe for disaster. The stocks may not go up, and may even go down, but you'll still have to pay back your loan plus interest. Fortunately, the market recovered from the 1929 crash, and the investors who held their positions in long‐term broad market index funds didn't lose a single penny.

The 1987 Black Monday crash

Black Monday (or Black Tuesday in Australasia due to time zone differences) is known as the biggest crash in stock market history, even larger than the 1929 crash. It's widely assumed that the market fell due to computer‐driven trading models that had made some errors. These computer systems were new to Wall Street and were basically tasked with engaging large‐scale trading strategies. The market fell more than 20 per cent in two days. Let that sink in: the biggest two‐day drop in the market was only 20 per cent. For someone investing in a broad market fund, at most, their stocks dropped 20 per cent suddenly. Not 100 per cent, not 80 per cent, not even 50 per cent. To date the biggest two‐day drop of the market has only been 20 per cent.

Now you may be wondering how some people say they lost almost 90 per cent of their portfolio in this crash. Investors in training know that when someone says they lost a huge chunk of their portfolio, it was because they took on a greater risk to begin with by investing in individual stocks. The value of a single stock can rise and drop much more rapidly than the entire market. You can lose 90 per cent of a single company in a day, but it is very difficult for a broad market index to drop 90 per cent in a day — nothing like this has happened yet. Despite being the biggest crash, the market recovered only three years later in 1990. Meaning those who held their positions, again, didn't lose a single penny.

The 2001 Dotcom Bubble

It's probably equal parts morbid and nerdy to have a ‘favourite’ crash, but the Dotcom Bubble will always be my favourite. It was the perfect storm and a great example of what an investing bubble is: a market phenomenon where the price of certain stocks, industries or the entire market gets inflated much higher than what it’s actually worth (like paying $100 for a $20 beauty blending sponge), until prices aren't sustainable and thus the bubble ‘bursts’. It's like when you tell a little lie that keeps getting bigger and bigger until it all comes crashing down — everyone sees through your BS and walks away.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the internet was the ‘next big thing’ and internet companies were popping up everywhere. Any public company that had ‘.com’ after their name began soaring: think pets.com or toys.com. Even if the company wasn't making a profit, enough speculators invested to artificially inflate its stock price. Because they thought they were going to make big bucks.

When the growth of investing into these empty companies wasn't sustainable, the market dropped. Those who had been trying to pick the next big thing were left burnt. However, again, the market fully recovered by late 2006, and those who were holding their positions in long‐term broad market indexes didn't lose a single penny.

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis

You're probably familiar with the GFC. Even those who weren't directly involved or old enough to understand what was happening had a fair idea that ‘the entire world was suddenly poorer’ — and they weren't exactly wrong. In 2007, subprime mortgages (bad mortgages with high interest rates given to people with incomplete credit histories) were being handed out in the US like hot dogs on a street corner. People were even being paid to take up mortgages, a concept that leaves many millennials and Gen Zs today in disbelief.

Eventually, these dodgy mortgages started to catch up to people; homeowners weren't able to repay them anymore, defaulting on their loans and causing a large decline in housing prices. Lehman Brothers, a financial services firm that was in charge of a lot of these ‘bad’ mortgages, declared bankruptcy, putting Wall Street in big trouble. The stock market crashed, losing 46.13 per cent over the course of 18 months from October 2007 to March 2009, but recovered entirely in four years, by 2013. It then continued on a 10‐year winning streak, up more than 250 per cent from 2009 to 2019. Again, those who were holding their positions in long‐term broad market index funds didn't lose a single penny.

The 2020 COVID‐19 crash

The most recent crash was the infamous COVID‐19 drop in March 2020. When the world went into lockdown, the market momentarily dropped on 9 and 16 March. Investors in training know a crash is a buying opportunity, not a moment to panic. What we didn't know at the time was that the market was going to bounce back incredibly fast: 33 days, to be precise. That's almost half the length of Kim Kardashian's marriage to Kris Humphries. Most analysts predicted the crash would last much longer — after all, these were ‘unprecedented times’. To everyone's surprise, the market went on to one of the fastest rises we've had in recent times. And again, those who held didn’t lose a single penny.

***

Investors in training can see a clear pattern throughout history with every market drop. They aren't worried when the market becomes volatile in the short term because, if they are investing their money for the long term, the risk of losing money when investing in a broad market, low‐cost fund is low. It's not impossible, but it's incredibly low.

Having this knowledge under your belt provides investors the confidence to ride through the ups and downs of the market.

Myth #2: Investing is like gambling

A lot of people worry that investing is like gambling. Let's role play for a second. Your name is Priya, you're in your best outfit and you're walking up the stairs to a shiny red carpet surrounded by bright flashing lights. It's not the Met Gala, but rather your local casino. You head over to a slot machine, the playful colours inviting you over. As you sit down, you hear the dings of the slot machines around you as players cash out. The sound is purposely engineered to arouse your senses and entice you to play.

You open up your wallet and put $500 into the machines. It's a lot of money, but you're willing to take a chance.

You're not just any ordinary gambler at the casino, though — you've done your research. You know the return on gambling is low. So low that you're aware the likelihood of making a return ranges from one in 5000 to one in 34 million.

After all, slot machines work with a random number generator inside every machine, cycling through millions of numbers and options.

You also know that in a casino, each time you play a game, the statistical probability is that you will not win. In fact, the more you play, the more the statistics work against you and the higher your chance of walking out of the casino with a loss.

Now, imagine you had a twin sister, Anu. Anu decides gambling in the casino isn't for her, and decides to look into stock market investing. She chooses to take $500 and invest in a Vanguard Total Stock Market Index Fund ETF (VTI), a fund (or basket) that is made up of every public company in the US. Anu now gets to own a small piece of everything from Apple to Zoom to some of the casinos themselves.

If Anu did this every month for 20 years starting from 2002, she would have likely made a 400‐plus per cent return on her money.

If Priya returned to the slot machine with $500 a month every month for 20 years, the odds of her making anywhere near that return, let alone a positive return, is very slim.

Investing and gambling both involve risk, but that's where their similarities end. Gambling is a short‐lived activity that involves chance, while investing involves choice.

When you're gambling your money, you don't control a lot of things. You can't research the dice beforehand, you can't read its company statements. You can't decide that the dice have a strong future outlook. It's all based on chance and speculation. And gamblers have fewer ways to mitigate risk compared to investors. If it comes down to odds, the odds are in your favour as an investor.

Investors are able to decide on their risk profile and invest in companies and funds that align with that profile. Investors are able to research their companies, see their past performances, understand their products, read their future forecasts and make decisions based on merit. Investors can read about the value of a company and decide if they wish to invest in them or not.

One of the most common misconceptions that lead people into thinking investing is like gambling is the misunderstanding of what investing is. Some people think it involves taking money, throwing it into a few companies and hoping for the best. That is what is called speculative investing: putting money into a company because you assume, or speculate, without any research, that the company will do well, or continue to do well based on past performance.

An example of this was the GameStop rally of 2021, which we discuss in more detail in chapter 9. Another example was the Tesla boom in 2021. Many investors saw Tesla ride upwards and couldn't see the stock dropping anytime soon. See figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Tesla shares dropping

Source: Courtesy of Nasdaq

Unfortunately, as many investors of the time know, in November 2021 Tesla's shares finally began to fall into a correction.

A correction is when the prices of the stocks begin to fall because everyone wakes up and realises around the same time that they’ve been paying too much. Corrections are different to crashes, by the way. In a correction, prices only fall around 10 per cent. In a crash, prices fall more than 10 per cent.

On 9 November alone, Tesla stock fell 12 per cent. Investors in training who did their research would have noted the warning signs that Tesla was an overpriced share. You see, Tesla shares were forming what is called a speculative bubble. This is when shares are being bought not because they’re a good choice, but rather driven by greed and the assumption that the price of those shares ‘will never drop’. Clearly they hadn’t taken on Bieber’s advice to ‘never say never’.

Four warning signs of a speculative bubble:

- new investors who are not interested in the commodity but rather the short‐term price gains

- rapidly rising prices that don't reflect the company's performance or future outlook

- lower interest rates, which encourages more borrowing to invest

- increased media attention, which then attracts even more investors.

Speculative investing is not the way most investors create good investing habits; the majority of long‐term investors prefer to keep speculating to a minimum and instead invest in companies and funds that they believe in, that they've researched and that align with their views.

Investing is all about intentional choices, while gambling is all about chance.

Myth #3: Investing is complicated

When I studied financial markets, I still remember gritting my teeth through my first lecture — reminding myself again and again that I just needed to believe in my ability to learn and understand the content. By the end, I was almost angry at how simple investing actually was, and how many years I had wasted thinking investing was too hard for the everyday person.

The truth is,

thinking that investing is too hard is a popular myth that holds most of us back from getting started.

We think that there must be some complicated process that goes on behind investing and that, because it is an activity primarily dominated by rich white men, with almost 90 per cent of fund managers in the US being male according to a 2021 Citywire Alpha Female report, it must somehow require more intellect or skill than the average person has.

I'm not sure who decided that if a white male does something, it must automatically be more complex compared with the jobs that women traditionally do. I think part of the issue is that representation does, in fact, matter. Famous female investors are few and far between: Sallie Krawcheck, hailed as ‘one of the last honest brokers’, is one of the few investors who made it to the front page of the Wall Street Journal, and even then she was only there because of her public firing.

The investing industry did a really great job at perpetuating this myth for as long as they possibly could. After all, fund managers make a lot of money when someone thinks it's all too complicated and would rather pay the fund manager a cut of their entire investing portfolio. Gatekeeping investing keeps certain people in business.

Now, I do want to note that there is a time and place for professionals in all areas. In some circumstances, it makes sense to hire a fund manager to invest for you, for example, if you inherit a large sum of money after a death in the family and aren't emotionally in the right frame of mind to invest yourself, or if you would like a hand to hold during the ups and downs of the market. Sometimes people with ADHD or other neurodivergent tendencies would benefit from having an adviser who provides assistance as required. There is no one right or wrong way to invest, but this book will teach you how to determine the best way for you.

You don't need a degree in finance to invest for yourself. The skills needed to invest are so simple once they are broken down. To this day, I've never met a person who couldn't understand how to invest in the stock market once it was explained in a way that made sense to them. The Girls That Invest community is made up of women, men and nonbinary folk whose education levels range from those who didn’t complete high school, to those with doctorate degrees. We even have people telling us that their bachelor's degree in economics or accounting hadn't even explained investing clearly. Due to their lecturers knowing the subject so well, it was almost difficult for them to articulate it in a way a beginner could grasp.

Let me set the record straight, investing does not involve many graphs and hours of following trends. It doesn't involve large risks and calculations. To buy a stock you no longer have to call up a broker and hear them pressure you into investing in the next hot thing. Thanks to recent technology, investing in a company or fund is as simple as going to an online store and buying a top. But rather than clicking on a Nike shirt, you click on the Nike company and take it to the checkout. And just like that, you become an investor.

Investing may not be complicated, but the jargon is …

There's no doubt the jargon is a huge barrier to entry. It's almost like another language. There are so many unnecessary words that prevent us from learning about investing on our own.

For example, if the prices of stocks are collectively rising, investors will say ‘there's a bull market'. Or if stock prices are falling, they'll say there's a ‘bear market’. Instead of saying ‘What companies make up the bulk of your investments?’ they ask ‘What positions are you primarily holding?’ As mentioned earlier in this chapter, ‘margin investing’ is when people invest in stocks with borrowed money.

Or my favourite, rather than saying Apple's stock price has gone down by 0.5 per cent, they'll say ‘Apple dropped 50 points’.

‘What on earth does 50 points mean?’ was the first thing that came to my mind when I was learning how to invest. I thought it would make sense to break it down for you too.

The points system is a way for investors to understand how a stock is performing: is it going up or down in value? 100 base points is equal to one per cent, so if Google moves up 100 points, it just means the Google stock is up by 1 per cent. Or if Meta moved down 500 points, it's down 5 per cent. Rather than speaking about the movement of a company in points, percentages are much more intuitive. ‘But that would mean people can understand investing, we don’t want that!’ said some financial rule maker, at some point in history. I assume.

You may be thinking, ‘Alright, so it's not difficult to grasp investing concepts, but what about the maths?’

Luckily for us times have changed and the calculations needed for investing are becoming easier and easier to find online. Investing education websites such as Yahoo Finance provide investors with resources so they no longer need to whip out their old graphing calculator to work out the numbers. In fact:

if there's an investing ratio or number you need to know, there's already an online calculator for it.

The calculations of investing aren't difficult to grasp, either. In chapter 7, I break down the only investing ratios and numbers you need to worry about, so you can safely ignore the rest of the noise and focus on what matters. You'll see what I mean. And then you’ll get angry for every instance someone made you feel like you couldn’t invest because you weren’t ‘good with numbers’.

Myth #4: You need a lot of money to get started

A woman once shared with me the story of how she approached a friend's father when she wanted to begin her investing journey. She was a young woman of colour, in her twenties, and eager to learn.

He simply told her if she didn't have a spare $10 000 it wasn't the industry for her, and she listened. As shocking as that comment is, it's a common misconception thrown around even to this day.

I used to believe this myself. In fact, I used to think investing was something I would learn about after I had a big house and boat; once I had a Kardashian‐sized mansion in Calabasas I'd look into what a share is. As a child, I thought investing was what people did with their money once they had already made it, and it was just a fancy place to store all of their excess wealth. (I also thought an investing portfolio was a clear file filled with pictures of people's investments and properties, but I think I may have been the only one.)

My fatal mistake was to think investing is what people did with their wealth, instead of realising investing is how people grow wealth in the first place. Through the effects of compound interest, you are much better off investing with what you have now than waiting until you have the luxuries in life. As discussed in chapter 1, your money works harder for you when you invest $1 in your twenties than $10 in your forties. It is, however, important to speak about context: if someone is barely able to afford their basic needs, then those needs should come before investing. But if you have a spare $50 at the end of the month that you don't need for the next three to five years, then it's not ‘meaningless’ to consider investing it.

Now, you would be forgiven for thinking you need $10 000 in order to invest. Not too long ago, to begin your investing journey, you really only had access to mutual funds — a pool of investments, such as shares of different companies, held in a basket — where the minimum to invest ranged from $1000 to $10 000. Fund managers made money through percentages of their clients' portfolios, so in their defence it made sense for them to take on clients with larger pools of money. Think about it: would you rather work with five people with $50 000 each or 500 people with $500 each? Fair enough.

However, now there is this beautiful thing called fractional shares. Fractional shares allows you to buy a per cent of a share. If an Alphabet share (Google’s parent company) was $1000, you don't have to wait to save up $1000 to buy one share. You can put in $10 and get 1 per cent of a Google share. Now, technically even $1 is enough to allow people to become investors in any company!

You may be wondering how on earth 1 per cent of a share is going to help you achieve financial freedom, but the benefit of owning even a fractional share is that your money goes up and down the same percentage that the entire share would.

For example, if Google retuned 20 per cent in a year, someone owning $1000 worth of Google would get a 20 per cent return on their money, but so would someone owning only $10 worth of Google stocks. You don’t have to wait to save up to be ‘in the market’ and have your money beginning to work for you.

The barrier to entry has never been lower. Investing is no longer just for the few rich and wealthy individuals who have a spare $10 000. Anyone can now have the chance to grow their investing portfolio, become an investor and create wealth for themselves in a way that doesn't rely on them exchanging time for money.

Myth #5: Real estate investing is less risky

Imagine if you had a pushy real estate agent called Mrs Housing. Mrs Housing comes to your home every day to announce how much the price of your home has changed in the last 24 hours. Today it's worth $500 000, tomorrow it's worth $490 000, meaning you've lost $10 000. The day after it's worth $15 000 less. The next day it's worth $10 000 more after the Manns next door sold their home for a higher price, bringing up the value of your home.

On a rainy day your gutter overfills and Mrs Housing lets you know you just lost $4000 in home value. On a day when you finally decide to weed your garden Mrs Housing pops by to say the value of the house just increased slightly: $500, to be exact.

Mrs Housing is a Type A personality so she tracks these movements every day on a spreadsheet and shows you a graph of how your house price is moving. She brings this graph every day, and you see just how volatile the housing market can be.

Many people perceive real estate investing to be less risky than stock market investing, but it's only because they don't have Mrs Housing updating the price of their assets daily. Homeowners would consider their housing assets a lot more volatile if they saw these daily movements. Instead, homeowners only really note their house prices a couple of times: when they're about to buy their home, when they remortgage it and when they're about to sell it. The average time between buying and selling your home is usually 7.4 years. If a stock market investor in a broad market index also only checked their index fund every 7.4 years, they wouldn't consider the stock market to be as risky.

Unfortunately, in the stock market this data is updated every second.

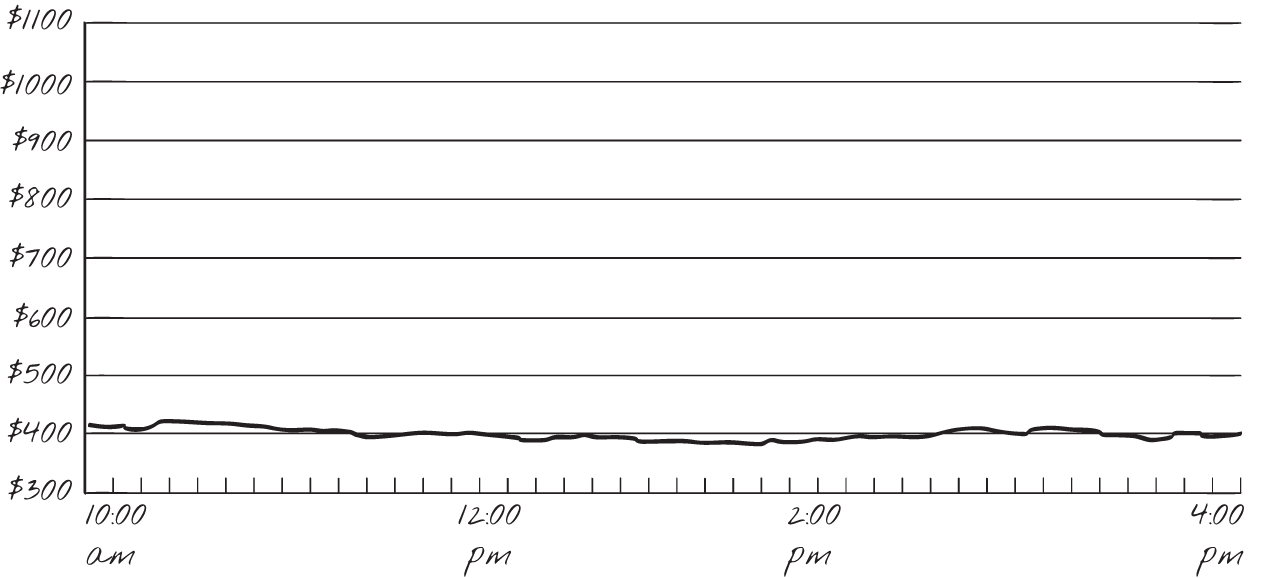

For example, take a look at figure 2.3. To the average person this may confirm their concerns that the stock market is too volatile. It's a graph of the Vanguard S&P 500 exchange‐traded fund (ETF VOO), made up of the top 500 companies in the US, displaying its movement over the course of a day.

Figure 2.3: a day with the ETF VOO

Source: Used with permission of NYSE Group, Inc. © NYSE Group, Inc.

The highs and lows on this graph appear scary, yet all it's showing is that if you had one stock of this ETF in the morning it was worth $403 and by the afternoon it was worth $397 — losing a mere $5, or 1.2 per cent in value. Investors in training know the important of reading the scale when reviewing the performance of shares. It can be the difference between something looking very volatile versus something looking flat, depending on the scale of the Y axis (the vertical axis), as shown in figure 2.4 (overleaf).

Home ownership isn't all roses either. There are also risks that come with it, unlike stocks that can be liquidated quickly into cash if you need it, when it comes to real estate investing you don't get the cash in your wallet until you have sold your asset, which can mean waiting weeks, months or in some cases even years (especially in the luxury market), which is a risk in itself. You also have the risk of property damage, bad tenants or poor weather events. People could even egg your investment.

Figure 2.4: same data, different scale

Source: Used with permission of NYSE Group, Inc. © NYSE Group, Inc.

Another thing to point out is that in this economic climate, home ownership is not the easiest form of investment to get into. Wages aren't keeping up with the cost of living or house prices, and many young people are finding themselves pushed out of the market, but still wanting long‐term wealth generators. I had a very similar experience: I couldn't afford a home just by saving, so I chose to invest through the stock market, which eventually helped me to get into my first home. If you don't have parental help (I didn’t), investing in the stock market can sometimes be an option to work toward property ownership in the long term.

While property isn't a less risky investment, some may prefer property as it's an asset that they can see and touch, and therefore feels more real and grounded. Some investors find that owning a home can be a good investment as you can do up the place to add value, and you're more in control of the asset as you can decide on rent, who your tenants are and any changes you want to make. One of the biggest benefits of property investing is that you can also use it as leverage: you're borrowing money from the bank via a mortgage, but the increases in the property price of your home you get to keep. The truth is the stock market often outperforms how fast property prices rise, but that thing called leverage is why many people look into property.

Real estate is not a bad form of investing, but it's not the most accessible form of investing for the average investor. The risks involved in real estate and stock market investing vary, but in the same way that you can purchase bad stocks and lose out, you can also do so with bad homes.

***

There are many myths that surround stock market investing, and I'm never upset at any of them. It's human nature to protect ourselves from the unknown, and in this context that protection can look like statements that suggest investing is like gambling, or that it's too risky. The truth is that once the information is laid out clearly it's very easy to cut through the noise and realise investing is an accessible and frankly wonderful wealth generator for investors in training to use.