CHAPTER

4

Compassionate Connected Care

IN 2013, BRANDY, a 36-year-old medical sales rep, was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. The fear of the diagnosis was bad enough for her and her young family, but it was made all the worse by the unnecessary anxiety and stress Brandy suffered while trying to advocate for herself when it seemed like no one in healthcare would.

Some 18 months earlier, Brandy had started to feel run down. She was just overworked, she thought. But was she? She was feeling cold all the time, sleepy, angry—just plain bad. To cope, she drank energy drinks and took naps in her car between surgical cases (her job was to sell interventional spine implants and help with them during surgery).

Pretty sure that something wasn’t right, she went to her primary care physician, but he told her she was likely just experiencing the normal symptoms of aging. Brandy wanted to believe him, but six months later, her symptoms still hadn’t improved. She talked with other providers, hoping that they might take her symptoms more seriously. Yet they, too, dismissed her problems and wouldn’t order any blood tests.

Brandy trudged on with her life as best she could, hoping that her caregivers were right but afraid that they weren’t. The turning point came in February 2013 when she fell asleep while driving to a surgical case in broad daylight after a full night’s sleep. Waking up on the side of the road, and thankful that she hadn’t hurt herself or anyone else, she went back to the doctor that very day. Her symptoms hadn’t abated, and her neck hurt all the time. She wanted a blood test.

He still wouldn’t do it. “What you need,” he said, “is a pain management physician.” So that’s where he sent her.

Brandy happened to know the pain management doctor from her work in the OR, so she texted him and asked if he’d order labs for her. The physician did so, and her labs came back abnormal—and not just a little. They were way off. Noting that she’d had a double-shot espresso right before the test, the primary care physician told her that the results probably reflected the caffeine in the drink. She was fine, he assured her. A medical student who happened to be in her physician’s office that day felt her thyroid, which was swollen. “You definitely need an ultrasound,” he told her. After much discussion, the primary care physician finally agreed to order one. The ultrasound confirmed what Brandy in her heart already knew: there was something big and solid in her neck that wasn’t supposed to be there—a larger nodule on the right side of her thyroid and a smaller one on her left.

Even at this point, she couldn’t get her doctors to take her seriously. The endocrinologist told her that he wasn’t going to biopsy the nodules. As a sales rep in the operating room, Brandy had been exposed to a certain amount of background radiation from the two C-arm imaging machines and live fluoroscopy. She knew that she was supposed to wear a thyroid shield, but the shields weren’t always available. “Everyone has nodules if they’re exposed to radiation,” the endocrinologist told her. “Nothing to worry about.” Brandy insisted on a biopsy, and a good thing. Twenty-four hours later, the endocrinologist called her with the news: differentiated papillary thyroid cancer.

Some weeks later, Brandy had her thyroid removed. She followed up with radioactive iodine to kill any remaining thyroid cells. For almost four years, stretching into 2017, she was largely symptom-free. Then in April of that year, she began to feel tired again. More lab work and an ultrasound revealed bad news: she had a tumor on the left side of her neck. This time, it was metastatic in her lymph nodes. Her doctors didn’t feel a biopsy was necessary. The tumor was likely slow-growing, so they could just keep an eye on it for now.

Brandy wasn’t so sure. All this time, her care providers hadn’t listened to her. She called friends who knew friends at MD Anderson Cancer Center, and she quickly booked an appointment with a thyroid cancer specialist. As of this writing, she is still undergoing tests and will likely have more surgery soon. Brandy is scared for herself and her family—and frustrated that it has taken so long and required so much effort on her part for her doctors to take her concerns seriously. Why were caregivers seemingly so disconnected from her needs, fears, and perspectives as a patient? Why hadn’t they cared enough about her to put aside their assumptions about “patients like her” and listen to what she was feeling in her body?

Experiences like Brandy’s are frighteningly common. They continue to occur not just because of the causes of suffering described in Chapter 2, but because individual providers, teams, healthcare organizations, and the industry as a whole haven’t quite known what to do to improve patient and caregiver experience. They’ve understood that healthcare is chaotic and patient experience subpar, so they’ve tried mightily in recent years to improve that experience (without framing it as suffering per se). How they’ve focused, however, has missed the mark. Much of the time, organizations, teams, and individual caregivers work on improving specific scores relating to patient experience. That makes sense—the scores drive reimbursement. But a constant focus on scores obscures the greater challenge: to create an entire system, a culture, in which patients are at the center of care. If Brandy’s providers had oriented their work in fundamental ways and at every level around her, they would have listened to her and showed compassion instead of dismissing her concerns time and again. Quite possibly, they would have caught her cancer earlier. At the very least, they would have reduced unnecessary suffering.

We can’t just address particular metrics on a piecemeal basis and hope to make progress on suffering. If it were that easy, healthcare organizations wouldn’t see the many patient problems, the negative comments, the poor scores, the turnover, and the burnout they see today. To make progress, we must embrace a comprehensive approach toward patient experience, one that locks our attention on the real meaning of what we do and why it’s important.

Individuals and organizations want to improve healthcare for patients and caregivers. They feel like they’ve tried everything, and nothing has worked. I speak daily with healthcare providers and administrators who are perplexed about their scores and who feel demoralized. “We’ve done service training,” they say. “We’ve implemented hourly rounding and bedside shift reports, we’re doing leader rounding, but the scores are not reflecting it.” Or they’ll say, “You know, we’ve got great engagement scores for our employees, and our patients say they’d recommend us, but the rest of our patient experience scores don’t really reflect that.” These comments always follow with, “What do we need to do now?”

Any performance improvement or quality initiative needs an overarching framework to help bind goals and strategy together. And any organization likewise needs an overarching mission, vision, and values to organize people and bring them together behind a common purpose. Patient experience is no different. We need a methodology that brings disparate groups of people together around the goal of reducing suffering, that helps them remember why they wanted to become caregivers in the first place, and that provides a structured approach for actually accomplishing that goal. But where can we find such a methodology?

Building a Model to Tackle Suffering

For the past several years, we at Press Ganey have been researching, developing, and deploying a model that we call Compassionate Connected Care. I began creating Compassionate Connected Care back in 2013, when Dr. Tom Lee first joined our organization as chief medical officer. Tom and I spoke on a number of occasions about how we would provide a consolidated vision for clinical thought leadership at Press Ganey. Early in his career, he told me, he had a mentor, Lee Goldman, who helped Tom develop his own “brand” as a thought leader. Tom said that conceiving of thought leadership in terms of branding had helped him to focus his efforts around topics that mattered to him, with an eye toward his legacy. “What will your legacy be?” he asked me. “How will you define your brand?”

These were good questions, and I had to take time to reflect on them. I first told Tom that my brand was the totality of the patient experience and all things nursing. But he encouraged me to think about making a difference in a more specific way. So I pondered some more. What was really most important to the patients I served as a nurse and to the caregivers I served as a healthcare leader?

Thinking back to my colleague Deirdre’s notion of met and unmet needs as a way to measure suffering, I had an epiphany. Healthcare organizations had been collecting data about patient experience, engagement, and clinical quality for years. Often, we had monitored it to the point of “analysis paralysis.” We looked at the data all the time but never actually did anything with it. Or if we did take action, we never managed to sustain the gains. What we needed, I realized, was a new way of looking at the problem of suffering that would enable us to take more effective and sustainable action. We needed a framework—an action model. With Tom’s support, I set about creating one.

I spent a great deal of time researching the concepts of empathy and compassion, watching Cleveland Clinic’s 2013 empathy video, which I felt poignantly demonstrated the need for empathy and compassion,1 and contemplating the definition of words like “sympathy,” “empathy,” and “compassion.” According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “sympathy” is a feeling that one might have “of pity and sorrow for someone else’s misfortune.”2 When you can understand that misfortune from the inside, and when you can actually communicate what it feels like to someone else, you’ve achieved the ability to empathize.3 Meanwhile, the Cambridge Dictionary defines “compassion” as “a strong feeling of sympathy and sadness for other people’s suffering or bad luck and a desire to help.”4 That “desire to help” is crucial, leading us to think of compassion not as a noun but as a verb. Compassion is the action you take when you feel sympathy or empathy.

Earlier in this book, when I told you about how my son-in-law, Aaron, was shot, you might have felt sympathy for me. You could imagine what it must have felt like to have been in that situation. But perhaps you not only understand that police violence proliferates in society today—you also know firsthand the devastation caused by a bullet to the brain. Or perhaps you can also imagine the devastation that the patient’s family is experiencing because you’ve seen or experienced that yourself as a caregiver. In fact, perhaps you can imagine it so well that you can communicate that understanding to me. You might have even cried at hearing Aaron’s story or wanted to reach out and hug my daughter. What you experienced was empathy. And let’s take that one step further. Perhaps in your state of empathy you wanted to do something to ease my daughter’s or Aaron’s pain. That action is compassion.

Following this logic, I concluded that all of us in healthcare require compassion to reduce suffering. But I realized that compassion alone wasn’t enough. Obviously, our clinical skills and expertise mattered as well in order to provide the best possible outcomes and safety. Empathy and compassion don’t make much of a difference if patients suffer from hospital-acquired pressure injuries, falls, and infections. But thinking about suffering further, I concluded that even compassion and good clinical care weren’t enough to reduce suffering. Somehow, we needed to connect compassion with high-quality clinical care, and we had to focus on connection in general and in its own right.

Conceptualizing Connection

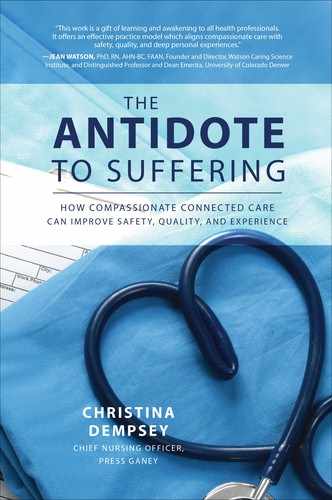

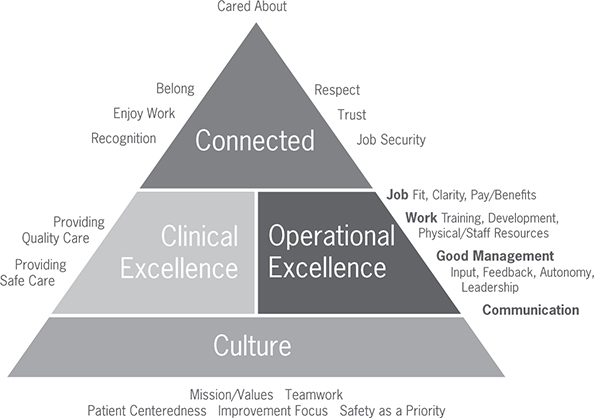

As I had seen firsthand during my cancer treatment, care was frequently fragmented and disconnected, on every level and in every sense of the word. To reduce suffering, I felt, we had to remedy this systemic and almost existential quality of healthcare. Yes, the model we were creating had to connect compassion with clinical excellence. But we also had to connect many other elements with one another. In particular, based on my past experiences in healthcare, we had to make four specific connections in order to mitigate suffering: those relating to the clinical side, the operational side, the behavioral side, and the cultural side of healthcare (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 The Compassionate Connected Care model

First, our model had to connect clinical excellence with outcomes. I may put in the best central line around, but if patients get infected, it doesn’t matter how well I placed the line or how many I put in. It’s the outcome that matters. Increasingly, patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) are helping to measure not only the clinical outcome but the functional outcome as well. If I have a total knee replacement and leave the hospital without an infection, fall, or pressure injury, but I am not able to walk 20 feet unassisted after two weeks, then my outcome is not what it should be. Again, who cares how excellent my surgeon and nurses were? The net result is I can’t walk 20 feet. Since every person involved in my care has an impact on my outcome, attending to outcomes as well as clinical excellence and process measures means taking steps to help teams work better together. We need to remember that we’re all in this together, and so we all need to help to facilitate the desired outcome.

Second, our model had to connect healthcare quality with the efficiency of operations. A healthcare organization that spends 10 times more than its competitors on high-quality care may well deliver it, but it does so at an unsustainable cost. No business owner would accept a 3 percent margin year-over-year, and yet hospitals and healthcare organizations do. They thus have no choice but to deliver both quality and efficiency. As the sisters said to me many times in my career at a large, faith-based organization, we must understand the reality of “no margin, no mission!”

Think of it this way: those who pay for and partake of healthcare expect clinical excellence. But operational excellence (efficiency) assures that hospitals have the financial, material, and collaborative resources they need to make exceptional clinical care happen. When I worked with organizations to improve flow, many hospitals wanted to focus on the emergency department (ED), where the operational issues seemed most obvious. I couldn’t blame them: the ED was exhibiting long wait times, poor patient satisfaction, high turnover of talent, and many other problems. However, when I examined clinical and operational data relating to triage, door-to-provider times, total time spent in ED, disposition to inpatient bed placement or discharge, interaction between staff and physicians in other areas of the hospital, and diagnostic testing turnaround times, it became obvious that focusing solely on the emergency department would not suffice. The hospital faced systemic issues, and it needed to address them systemically.

Why, for instance, were patients waiting? Well, in some cases, the emergency department couldn’t obtain needed results from the lab or imaging department in a timely fashion. In other cases, hospitals required that a hospitalist see a patient in the ED prior to inpatient admission, but it took an hour or more for the hospitalist to make it to the ED. In still other cases, a social worker or case manager wasn’t available, or no staff was available to accept the patient when he or she arrived on the inpatient floor. In all these situations, the patient waited. And waited. And waited.

So often, EDs felt isolated and at the mercy of inpatient units, and in many ways, they were. But in order to achieve operational excellence, these emergency departments had to recognize that they and the rest of the hospital were in this together. In my work, I helped form flow teams in the ED that consisted of ED physicians, nurses, techs, lab representatives, pharmacy personnel, hospitalists, cardiologists, surgeons, imaging specialists, and administrators. The broad representation of specialties assured that recommendations coming out of this group were realistic and within its purview. We examined data around key process indicators and defined common goals. The operational changes that resulted led to significantly shorter wait times in the waiting room, higher patient experience scores, and better engagement. Working collaboratively, we confirmed that operational excellence, clinical excellence, and patient experience went hand in hand.

If our model to address suffering forged links between efficiency and quality of care, it also had to make a third connection: between engagement and the behaviors that contribute to it. Having surveyed the behavioral aspects of patient experience, Press Ganey was keenly aware of the connection between caregiver engagement and the behaviors caregivers needed to render in order to provide an optimal patient experience. Employees in organizations that ranked in the top quintile for engagement scored higher in patient experience on every domain of HCAHPS. As we discussed in Chapter 3, HCAHPS evaluates behaviors on a frequency scale—how often teams exhibited desirable behaviors—while the Press Ganey survey evaluates behaviors on a Likert scale, charting how well those behaviors were exhibited.

Of course, the consistency with which these behaviors are exhibited also matters. If 90 percent of employees demonstrate 90 percent of the necessary behaviors 90 percent of the time, that seems pretty good, right? Almost everyone is performing most of the desired behaviors pretty much all the time. That’s A-grade performance. But hold on. Multiply 90 percent by 90 percent by 90 percent. You arrive at 73 percent—meaning that the hospital is only satisfying patients 73 percent of the time. That will put you in the tenth percentile of hospitals, and nowhere close to maximizing your value-based purchasing reimbursement. A 73 percent is a “C” grade—average at best and definitely not “very good.” The reality is that patients deserve caregivers who perform 100 percent of behaviors 100 percent of the time. Would you want your family members to experience the 10 percent of care encounters in which providers missed opportunities to minimize or mitigate your suffering?

As we saw in Chapter 2, young caregivers often don’t learn the behaviors required to mitigate or avoid suffering in school, nor do they receive the coaching they need to make those behaviors automatic. “Seasoned” caregivers may forget these necessary behaviors when they become jaded after years of work. So what does “showing courtesy and respect” really look like? We feel its absence, and we know it when we see it, but do we teach it and demonstrate it to one another and to our patients every time? Do we always provide information that makes our patients feel safe and successful when they leave us for additional care? Do we often give patients a chance to influence care decisions, helping them to feel at least some autonomy in a process that seems totally out of control? Again, what do these behaviors look like? We need to proffer the training, coaching, and moment-to-moment affirmation that allow all caregivers everywhere to understand and adopt these behaviors.

A fourth and final connection that our model for reducing suffering made was that between engagement and the organization’s mission, vision, and values—its culture. When I was a new nurse, I walked to the elevators every day on my way to my unit, and I stared at the framed document on the wall next to the elevator button—our mission, vision, and values. I never really gave the plaque much thought, and I didn’t connect it to my own purpose as a nurse. Today, I realize that mission, vision, and values constitute the most important information to pass on to employees, not to mention patients and visitors. Without that shared purpose, individuals, teams, and organizations can never achieve their strategic goals. We will all work myopically to do the right thing as we see it, and we won’t understand how our little area of work fits into the larger organization and its mission. We’ll address suffering in a piecemeal fashion, and perhaps in ways that conflict with how other individuals and teams are addressing it.

One of the best CEOs I ever worked with carried a pocket-sized version of the strategic plan for our health system. At the top of this document, the mission, vision, and values were printed. Whenever someone made a request of him or suggested a change in a policy or practice, he would take out this little document and ask the person how the request or suggestion was integral to the organization’s larger mission and mandate. Every meeting included a discussion about how the agenda connected to the mission, vision, and values. My colleagues and I all understood that the mission, vision, and values weren’t just words on a plaque—they truly drove the strategic direction and decisions for our organization. Over time, this CEO and his team succeeded in creating a culture that reflected the mission, vision, and values of the organization. To this day, when I pass the hospital over which this CEO presided, I feel proud of that culture and the organization it sustained.

In 2014, I encountered a great example of how a strong culture can improve patient experience and reduce suffering when I visited the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s hospital. Its CNO, Dr. Mary Tonges, and her team had implemented a program there, based on Kristin Swanson’s Caring Theory,5 to spread a culture of caring called “Carolina Care.”6 When I stepped into the hospital (without a name badge or identifying clothing), I was amazed at what I found. The greeter helped me out of my taxi and showed me to the check-in and information desks. Although not lavish or especially beautiful, the lobby was clean and comfortable, and everyone I encountered greeted me warmly and made eye contact. In a medical-surgical inpatient unit, a patient suffering from a chronic illness told me of the outstanding care he was receiving. In fact, since he often had to be admitted to the hospital, he made a habit of requesting this unit because the people there took such good care of him. The nurses on duty not only were able to tell me about Carolina Care but could explain how it informed everything they did. A unit secretary told me how much of a difference Carolina Care made for her, saying, “I own Carolina Care.” What an incredible statement! This woman was so proud of her work and her organization that she not only committed herself to it—she identified with it.

I asked Tonges how UNC had managed to instill such a strong sense of cultural ownership in her workforce. She told me that the organization had first worked hard to understand Swanson’s theory. Then the organization educated all staff, assuring that they knew what the cultural principles it had adopted meant both in general and as applied to their work. Finally, and perhaps most important, UNC branded the culture “Carolina Care,” affirming that the culture belonged to everyone who worked at UNC because everyone, even the janitors and food services staff, was a caregiver. After all, if you don’t provide direct patient care, you support someone who does.

I was impressed. Every organization, I thought, needed to do what UNC was doing, connecting engagement with the organization’s mission, vision, and values such that it was palpable for everyone at all times.

More generally, I concluded that healthcare organizations large and small needed to forge all four of the big connections I have surveyed. All these connections working together would give rise to the total patient experience, and careful attention to all these dimensions, combined with compassion, would reduce suffering. In sum, I concluded that the pathway to reducing suffering was the following: the provision of exceptionally skilled clinical care, in an environment that is efficient and effective, by engaged and resilient caregivers, in a culture that was driven by a shared purpose to achieve the optimal outcome for all involved.

Detailing Compassionate Connected Care

Once I had determined our framework’s basic structure, I gave it a name—Compassionate Connected Care—and began to develop the model further in its specifics. I decided to research how a large and diverse group of people conceived of the notion of Compassionate Connected Care. I asked hundreds of patients, clinicians, and nonclinicians to provide me with very clear descriptions of what this kind of care looked like to them. I wanted detailed mental images of behaviors involved—not “Compassionate Connected Care means that doctors and nurses communicate better with patients,” but “When the nurse comes in to take my blood pressure, he puts his hand on my shoulder to comfort me.” Those were the only instructions I provided to people when I asked them for images.

In all, 117 image statements came back, and I analyzed them using the affinity diagram method. Originating as a business tool, affinity diagrams allow you to sort a large number of ideas into groups in order to review, categorize, and assess them. With Tom Lee’s help, I sorted individual image statements into groups of three or more, eliminating duplicate or overlapping statements and discarding statements that conveyed abstract ideas (for instance, “The nurse was kind and empathetic”). From the remaining statements, six basic themes emerged as definitions of Compassionate Connected Care:7

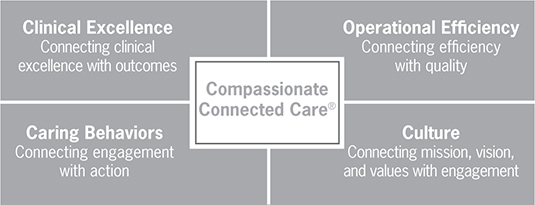

• Acknowledge suffering. We should acknowledge that our patients are suffering and show them that we understand.

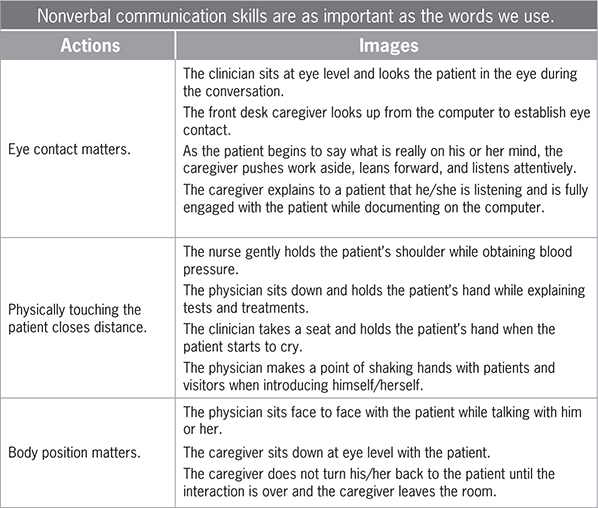

• Body language matters. Nonverbal communication skills are as important as the words we use.

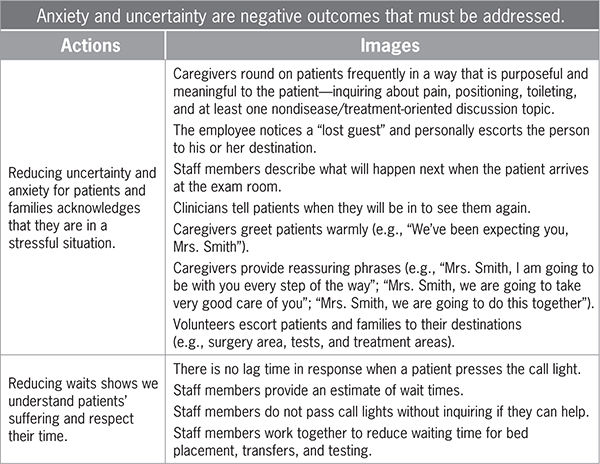

• Anxiety is suffering. Anxiety and uncertainty are negative outcomes that must be addressed.

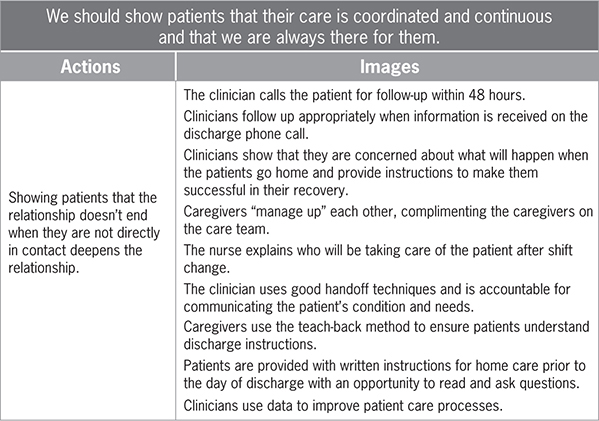

• Coordinate care. We should show patients that their care is coordinated and continuous and that “we” are always there for them.

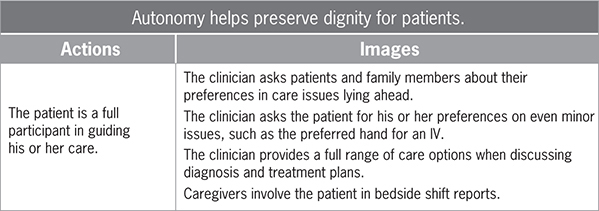

• Autonomy reduces suffering. Autonomy helps preserve dignity for patients.

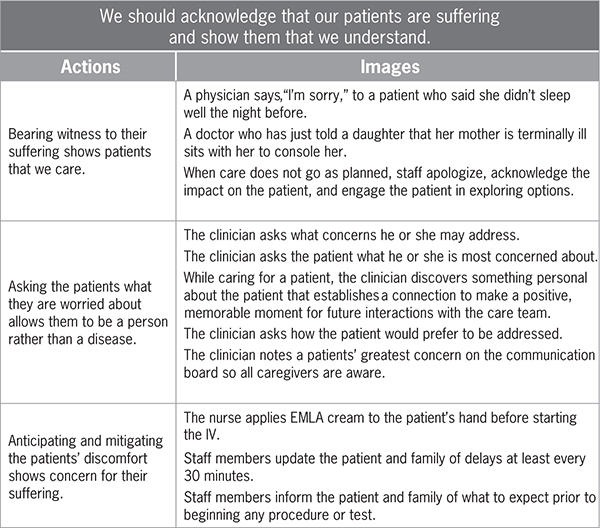

• Caring transcends diagnosis. Real caring goes beyond delivery of medical interventions to the patient.

In addition to these themes, the statements allowed me to identify specific actions that alleviate suffering in a variety of healthcare settings. Under “Acknowledge Suffering,” for instance, I uncovered actions such as bearing witness to the suffering (saying “I’m sorry” to a patient who wasn’t able to sleep), asking patients about their concerns, and anticipating and mitigating the patient’s discomfort. Under “Body Language Matters,” actions identified by my study participants included making eye contact, physically touching the patient (for example, gently holding the patient’s shoulder while obtaining blood pressure), and attending to one’s body position when in the presence of a patient (for example, not turning your back disrespectfully). Tables 4.1A–F in the following sections show behaviors for each of the Compassionate Connected Care themes.

Table 4.1A The Compassionate Connected Care Themes and Behaviors: Acknowlege Suffering

Table 4.1F The Compassionate Connected Care Themes and Behaviors: Real Caring Transcends the Medical Diagnosis

Let’s now run through these themes and their associated actions in a bit more detail.

Acknowledge Suffering

In Chapter 2, we detailed how healthcare education today limits the amount of time that students spend actually connecting with other human beings. As a result, students have a harder time acknowledging suffering and providing empathic and compassionate responses. In fact, many of them—and us—would rather send a text or tweet than physically speak with another person. To reduce suffering, therefore, we must consider closely what acknowledging suffering really looks like and how we can teach it to caregivers.

As a model for teaching it, we might adopt the SCOPE model of communication. SCOPE stands for “Solve the problem,” “Criticize,” “One-up,” “Probe,” and “Empathize.” Suppose Sally is a patient in your ambulatory practice. She presents today with a massive headache. As the provider, you ask, “What brings you in today?”

“I have the worst headache I’ve ever had in my life!” Sally says.

You can respond to this statement by doing one of the following:

1. Solve the problem. You might give Sally medicine for her headache, wash your hands, and leave the room. You feel great because you think you have solved Sally’s issue, so you move on to your next patient.

2. Criticize. You might say to Sally, “I doubt that your headache is really that bad. After all, you drove yourself here, and you were reading a magazine when I came in the room.” You might also scold Sally for taking up time that patients with “real” issues could have used. Clearly, criticizing is rarely, if ever, a good response.

3. One-up. You might say to Sally, “I get it! I’ve had a migraine for the last week!” Sally now feels understood, but she also likely perceives that you have minimized her concerns.

4. Probe. You might ask Sally more questions. “How long have you had this headache? What is the intensity? Where exactly does it hurt? Sometimes when you have a headache, it’s because you’re dehydrated. Have you had enough water to drink?” All of these are good questions that require answers, but they are not, ideally, the first thing you say to patients. Any idea what that is? Read on!

5. Empathize. You might say to Sally, “I’m so sorry you’re having to deal with this headache. It must be hard when you have things you want to do.” If you say something like this, Sally will feel both heard and validated by her provider.

In today’s fast-paced, technology-loaded, reimbursement-cognizant, and still largely volume-driven healthcare world, we all tend to behave primarily as solvers and probers. We want to solve the problem quickly, or ask more questions to solve the problem quickly. That way, we can move on to the next crisis or patient. It’s natural to want to do this. However, is it the wisest, most efficient, most compassionate course of action? What if after you empathized with Sally and validated her pain, she told you, “Yes, I’ve been under a lot of pressure lately. I’m going through a really nasty divorce.” Tylenol and water are not going to fix this problem. Sally is in crisis, and it has given rise, in all likelihood, to an intense headache. By empathizing, you have reached the root cause of her visit. Had you simply given Sally a Tylenol or asked about her symptoms, you would not have validated her concerns nor gotten at the root of her issue. You would have been addressing the wrong problem.

Body Language Matters

In my role teaching at Missouri State University, I typically have about 55 students in Nursing Leadership and Management, the last course in the university’s baccalaureate nursing program. Every semester, I send students to their preceptors, telling the students, “Follow your preceptors. Do everything they tell you to do, but I want you to do one thing differently. Sit down. You don’t have to spend any more time in the room or talk about anything differently; just sit down while you’re there. Come back and tell me how it went.”

Every semester, students come back and say things like, “That was amazing! The patients said we were better nurses than the nurses!”

One semester, a student came back to me and said, “So I tried your little experiment.”

“And how did it go?” I asked.

She responded, “Well, I sat down, and we started talking about fishing. I spent maybe a couple more minutes in the room, but not many. The weird thing was that the rest of the day, he never used his call light. And he never asked for pain medicine. And the next day, I wasn’t taking care of him, but his family sought me out to give me a hug and tell me thank you.”

Table 4.1B The Compassionate Connected Care Themes and Behaviors: Body Language Matters

Body language matters. When a provider sits down face-to-face with the patient and makes eye contact, the patient perceives the interaction to be both longer and more meaningful than if the provider spent the same amount of time but spoke to the patient while standing up.8 When our chief medical officer, Dr. Tom Lee, goes into a patient exam room, he sits down first, acknowledging the patient and empathizing with him or her. Only then does he begin to perform his exam. The process of acknowledging and empathizing doesn’t take long, and even when the chairs in the exam room are all filled, Tom says, “Sally, I really want to talk to you about your headache, so I’m going to go get a chair.” As Tom tells me, a family member in the room will invariably stand up and say, “No, no, take mine.” And he does. Or he goes and gets a chair. Because it matters.

Anxiety Is Suffering

Here’s something you should know: Every patient on a gurney, in a waiting room, in an exam room, or in a bed is scared to death. And their families are often just as stressed. Even when you go to the doctor for a routine exam, you have those niggling questions in the back of your mind: “I wonder what they’ll find? Will I be healthy, or will they find something wrong with me? How bad will it be?” If you’re there with a specific concern, the visit can feel even more harrowing. And let’s suppose you’re in the waiting room of the emergency department with your child, who has been coughing uncontrollably and running a high fever. You want relief for your child, and you also want the doctor to tell you that your child’s health problem is no big deal. But of course, your mind is also running through every awful scenario you’ve ever heard about or seen on TV. And you feel completely vulnerable and out of control, at the mercy of the people taking care of you.

Table 4.1C The Compassionate Connected Care Themes and Behaviors: Anxiety Is Suffering

None of us like these feelings; yet as caregivers we often forget that every patient we encounter experiences them. When human beings become frightened, we experience a physiologic response that dates from times when we had to contend with threats like saber-tooth tigers. It’s an autonomic response, and it kicks in when we’re confronted with something scary. Our heart rate accelerates. Our blood pressure rises. Our pupils dilate. We have to decide: Are we going to flee from the danger, or are we going to fight? This response is both normal and real. Unfortunately, when it kicks in, we don’t remember instructions very well, and we don’t follow them. We focus solely on the threat.

My own breast cancer diagnosis terrified me, even though I had been a nurse for 30 years, worked in multiple areas of the hospital, and taken care of thousands of patients. Of course, as an “old” OR nurse, the last thing I was going to do was let someone else pick my surgeon. So I interviewed my surgeons, narrowing my choice to two. The first surgeon was a great guy and had a wonderful reputation. I had known him for years, and he had even coached my younger daughter’s T-ball team. But when I went to my first appointment, his nurse was gruff, rushed, and a bit surly. I knew that I would interact with her more often than with my surgeon. Did I really want to have to deal with her sour demeanor on top of everything else? No, I did not. So I didn’t choose that surgeon.

I had hired the second surgeon as a patient care assistant in the OR before he went to medical school—it was his first job in the OR. That was 15 years earlier. I arrived early for my appointment and waited until my appointment time. Then I waited 45 minutes after that. I was growing frustrated and was thinking about leaving, but I waited another 15 minutes and the medical assistant finally called me to the exam room.

Once I got there, the staff members did everything right. They pulled the curtain to protect my privacy. They sat down when talking to me. They shook my hand. They asked not just about my diagnosis but about my family and my job. After the surgeon, Dr. Brian Biggers, performed his exam, he invited my husband and me to join him in his conference room. There, he answered every single question and did a genetic test for the BRCA gene right then, even though I told him that I hadn’t settled on a surgeon yet.

“Christy,” Dr. Biggers said, “I am the best there is at this. I’m fellowship trained. I have a low infection rate. I have great outcomes. No one can take care of you as well as I can. I’m the best.” Today, I chuckle thinking about what I would have done if he had said that when we were working together in the OR. I imagine that “arrogant” would have been the least of the adjectives I would have used! But as a patient, this was exactly what I needed to hear. I needed to hear that I was in the best place, with the best people, who were going to take the best care of me. In my moment of fearfulness, Dr. Biggers and his team made me feel safe. I no longer felt like I had to fight or run away from the threat. My stress level and fear decreased, and I could focus on becoming a full participant in my care.

I still feel good every six months when I go to see Dr. Biggers. I know that he is with me and that he’s going to take good care of me. I had the same experience with the plastic surgeon, Dr. Robert Shaw, who performed my reconstruction. These young surgeons were honest about what to expect and how much the procedures would hurt (and cost). They informed me about the risks and benefits of the procedures as well as of alternative care options. They were great clinicians, but the reason I will always be loyal to them is not their clinical ability per se. It’s that they reduced my anxiety by making me feel safe. All our patients and their families need that feeling of safety, too. And when they get it, the benefits rebound to caregivers.

In a well-known study conducted at Vanderbilt, researchers found that when physicians maintained a good relationship with their patients, the patients were less likely to sue the physician even if adverse events occurred.9 An analysis of plaintiff depositions revealed that over two-thirds of malpractice claims (71 percent) stemmed from difficult relationships between physicians and patients, with patients perceiving that physicians were uncaring. A quarter of malpractice plaintiffs faulted physicians for conveying medical information poorly, and 13 percent cited physicians’ poor listening skills.10

Coordinate Care

Healthcare is delivered in a wide array of settings, including the provider practice, outpatient clinics and therapies, acute care hospitals, surgery centers, rehabilitation hospitals and outpatient clinics, long-term acute care hospitals, hospice, home healthcare, skilled nursing facilities, and long-term care. As care continues to move toward a paradigm of population health management, organizations will increasingly have to assure that care is coordinated, provided in the best venue, and provided in the most efficient and effective manner. In Chapter 2, I referenced studies that show that patients may see between 60 and 100 different caregivers in a single hospital stay. Those numbers don’t take into account patients’ primary care providers, home health nurses, physical therapists, and others who may help with their care both before and after their hospital stay. Patients need to know that all these caregivers are talking with one another. Patients understand that we have to use electronic medical records, but are we actually using those records to coordinate? Does the primary care physician refer to what happened when the home health nurse visited? Do caregivers have to rely solely on the patient to learn about the plan of care?

Table 4.1D The Compassionate Connected Care Themes and Behaviors: Coordinate Care

As caregivers, we must show patients that we communicate with one another. We need to “manage each other up,” letting patients know that the next person who will be caring for them is going to take great care of them. And we truly need to collaborate with one another because it makes our patients feel safe.

Now, I will admit that when I was a staff nurse, I did like to blame issues like excessive wait times on the anesthesia or radiology department rather than on my own failings. “I’m sorry, Mrs. Smith,” I used to say. “I don’t know when you’re going to surgery. Anesthesia is behind again, and I’m not sure when someone will be out to get you.” It was easy to fall back on blaming anesthesia, because that department did always seem to be backed up. Besides, I wanted Mrs. Smith to know that it wasn’t my fault she was waiting—I was simply the messenger.

This response on my part might have served my purposes, but did it help Mrs. Smith? Not at all. Instead of making her feel safe, I was only worrying her more. Now she was thinking, Why is the anesthesia department backed up? Do they have enough staff? Will I get to go to surgery tonight? Will the staff be tired when they get to me? Will they take good care of me?” Thanks to my response, Mrs. Smith didn’t feel any safer than she had before. She felt less safe. I should have said, “Mrs. Smith, I’m sorry you’ve waited longer than you expected to. I want you to know that your anesthesiologist is Dr. Stewart, and he is a fantastic physician. He is going to take great care of you, and he’ll come and see you before you go back to the operating room. You’re going to be in great hands.” In responding in this manner, I wouldn’t necessarily seek to boost Dr. Stewart’s ego. Rather, I would seek to reduce Mrs. Smith’s fear, which, after all, is a very significant form of suffering.

Autonomy Preserves Dignity

When patients visit a provider practice or the hospital, they are told to put on a gown and store their clothes in a bag or closet. They are told when they can have visitors and how many. They are told when and what they can eat, when they can walk around, and how far. They are told when they can leave the facility and what they can do when they leave. They are told when the doctor or other caregivers will see them, operate on them, or perform a test on them. In short, patients lose all control. Sometimes they can’t even go to the bathroom when they want to or relieve themselves in private. This loss of control is often demoralizing, and it causes anxiety because patients feel vulnerable and at the mercy of those caring for them. I’ve heard many patients say, “I wish I could do it myself, but I know I’m not supposed to. I know how busy you are, and I hate to bother you. I’d much rather do it myself.”

Table 4.1E The Compassionate Connected Care Themes and Behaviors: Autonomy Preserves Dignity

Many times, patients can’t perform tasks themselves. But we caregivers often forget that some choices don’t really matter to us, and they might make all the difference for patients feeling deprived of choice. Here’s what it sounds like to offer more choice to patients when we can:

“Mrs. Smith, which arm would you like me to take your blood pressure on?”

“Mrs. Smith, would you like to take a walk in the morning or the afternoon? And when we walk, where would you like to go?”

“Mrs. Smith, you know that we have to document your information in the computer. Would you like to see what I’m charting right now, so you can tell me if I got it right?”

Affording patients a voice in issues such as these doesn’t require more time or resources. But by simply encouraging Mrs. Smith to make these decisions, we can ease her fears and help her to feel a greater sense of autonomy.

Real Caring Transcends the Medical Diagnosis

When I was in the hospital receiving treatment for breast cancer, the people caring for me didn’t see me as Christy Dempsey, a person with a family, job, hobbies, and dreams. Rather, I was “the mastectomy in 902.” I had lost my identity, as patients everywhere so often do. Sometimes they become their diagnosis, or their doctor’s name—“the Dr. Smith patient in 405.” Although this depersonalization may be entirely unintentional, it still happens, and it prevents us from connecting with patients, too.

Once when I was consulting in a large academic medical center, I was standing in the room of a patient who had open heart surgery the day before. The nurse practitioner entered, and there was no chair for her to sit in. Without hesitation, she knelt on the floor so that she could address the patient at eye level. She held his hand and talked about his family and his needs after discharge. She not only allowed him but encouraged him to make decisions about his care and how he would manage with his elderly wife at home. He was not the CABG in Room 408. He was Mr. Jones with a family, who needed to feel safe and who needed to be successful in recovery after discharge. Caregivers provide this kind of care every day, but we sometimes forget that we need to personalize what we do and connect with the people who happen to be patients at the moment.

On another occasion, when I was director of perioperative services for a large, level 1 trauma center, I used to watch a nurse named Sheila who took her role in the patient experience to heart. Sometimes Sheila spotted patients in the OR’s holding room who were trembling with fright. She took their hands and talked with them about their families, jobs, or hobbies. Then she spoke with them about the procedure they were about to have and what they could expect in the OR. She would help to transport these patients to the OR and help them onto the table, talking to them the whole time—not about the procedure, but about what she had learned was important to them in the holding room.

Just before the anesthesiologists would put these patients under anesthesia, Sheila would whisper in their ears: “I am going to be with you during the whole procedure. We will take good care of you. You are safe, and we are really good at what we do.” You could see these patients relax and then drift off into a peaceful sleep for the procedure. At these moments of peak vulnerability, when patients feared not waking up after surgery or waking up and feeling intense pain, Sheila was there. You see, she understood that providing care isn’t just a job. In the heartbreaking and inspirational memoir When Breath Becomes Air, Dr. Paul Kalanithi writes that our “duty is not to stave off death or return patients to their old lives, but to take into our arms a patient and family whose lives have disintegrated and work until they can stand back up and face, and make sense of, their own existence.”11 This is what we do. We heal. We comfort. We care.

Compassionate Connected Care for the Caregiver

As we discussed in Chapter 1, the people who care for patients are under tremendous stress and pressure. In many ways, they suffer, too. As we at Press Ganey began to talk about Compassionate Connected Care with clients and in conferences and publications, caregivers told us that the model helped them get back to the basics and rediscover the passion they had for their work. A number of these caregivers conveyed their wish that we create a framework for reducing their suffering as well. They knew that it was tricky to apply the term “suffering” to them. Unlike sick patients, they had known what they were getting themselves into when they became caregivers. Still, they felt the need to be heard and helped as well.

I thought about how we might utilize the same kind of action framework for the kind of suffering that caregivers experience, primarily stress, fatigue, and distress at work. Working again with Deirdre Mylod and Dr. Barbara Reilly, I reviewed a number of engagement surveys and methods for identifying, measuring, and distinguishing the experience of caregivers. We noted that the caregiver experience had several distinct dimensions (see Figure 4.2). First, clinical knowledge was a key part of caregivers’ work and professional identity. Second, caregiver experience had an operational component. Efficiency and effectiveness profoundly influenced the caregivers’ ability to succeed in their work. Third, caregiver experience was inflected by culture and the organization’s mission, vision, and values. In particular, culture enabled both engagement and good care for both patients and the people who care for them. Finally, we perceived that caregiver experience depended on a connection to purpose and the organization. In this last respect, the caregiver experience differed, in our estimation, from the patient experience, which hinged on caregiver behavior rather than connection with purpose. In all these areas, caregivers had needs that could be either met or unmet. To the extent that these needs were unmet, caregivers experienced suffering (see Chapter 3).

Figure 4.2 How caregivers experience care

Following a methodology similar to the one we used to generate the patient-oriented Compassionate Connected Care model, we asked thousands of caregivers—both clinicians and nonclinicians—to describe caregiving experiences that they regarded as compassionate and connected. Receiving 184 unique responses, we analyzed them using the affinity diagram method. Once again, we arrived at six themes:

• All of healthcare should acknowledge the complexity and gravity of the work provided by caregivers.

• Management has a duty to provide support in the form of material, human, and emotional resources.

• Teamwork is a vital component for success.

• Empathy and trust must be fostered and modeled.

• Caregivers’ perception of a positive work-life balance reduces compassion fatigue.

• Communication at all levels is foundational.

All caregivers want to perform well, but sometimes they feel hindered by the healthcare system, just like patients do. Many caregivers told us that they often hear about problems or issues that arise when they do something wrong—and that is fine. But they also need to hear that they do a good job when they perform well, and they need to hear that their work means something to patients and colleagues. As psychologists have long understood, positive reinforcement yields more sustainable changes in behavior than negative reinforcement. All too often, though, colleagues and managers only call attention to behavior when they wish to criticize it.

Managers in healthcare settings might think that they provide positive feedback, but do their team members perceive it this way? Consider how managers typically deal with adverse safety events. When such an event happens, they bring together the team involved to identify what went wrong. They take the event as their starting point and work backward, asking everyone involved to be honest and open. They identify what caused the failure and arrive at steps to take for avoiding it in the future. All this is as it should be.

Now, consider the last time you had a really good day at work or a time when a patient had a really good outcome, thanks to care in your unit, department, or practice. Did you take the time to understand the contributing factors? Did you pull the team together to deconstruct why the outcome turned out so well? Probably not.

The next time you have a really good day or you identify a really good outcome for your team, convene everyone around a conference table. Start by describing the good day or outcome and work backward. Ask team members why things went well. Was it the patient population? The team members who worked that day? The fact that the physicians participated in rounds? The way that the manager came out of her office to provide lunch relief? When you analyze the success and break it down into its component parts, your team can draw new insights about how to change practice, process, or policy going forward so as to replicate that success. And when team members perceive that such meetings do enable progress, they’ll feel acknowledged, and they’ll feel like they are active participants in the team’s success.

Analyzing the links between patient experience, nurse engagement, and clinical quality, we’ve confirmed that staffing is important, but we have also found that work environments might be even more so. In particular, work environments must enable caregivers to feel safe and to provide proactive care or surveillance capacity. These features of work environments depend in turn upon management’s ability to provide human, material, and emotional support to caregivers. To my surprise, none of the caregivers we surveyed told us that they wanted more money or better benefits. Rather, they asked for more emotional support in stressful situations, safe staffing, more equipment, and better maintenance or more frequent replacement of equipment. One caregiver wished for “an environment that is safe, nonjudgmental, supportive, empathetic, and healthy, so that the caregiver feels comfortable and encouraged to share concerns, questions, and suggestions for improvement and so that the caregiver can thrive in his/her role as caregiver to others.”

Significantly, the needs identified by these caregivers all reside near the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. They are physiologic needs, safety needs, and emotional needs. As Press Ganey’s research has demonstrated, managers cannot expect to achieve top engagement scores, low turnover, or top box patient experience scores until first satisfying these kinds of needs. Our first state-of-nursing report, released in 2015, identified the crucial role that work environment plays in the patient experience, nurse experience, and clinical quality, paying attention to falls, pressure injuries, and hospital-acquired conditions. Afterward, Press Ganey delved further into which aspects of the work environment drove key outcomes like intent to stay, overall rating, and clinical quality in terms of falls and pressure injuries. The results clearly demonstrated that the safety of nurses’ work environment, above and beyond surveillance capacity, greatly influenced how nurses felt about their jobs. It also impacted how they felt about their ability to contribute to patient care and intention to stay. All three of these considerations contributed to nurse engagement, which correlated directly with critical safety, quality, and patient experience outcomes and which influenced an organization’s financial health.12

As I began talking to healthcare audiences and clients about the six themes of Compassionate Connected Care for the Caregiver, I wanted to understand how each of the six themes ranked in the minds of people who care for patients. During a large, multidisciplinary conference, I used polling software to ask my audience of 500 caregivers to prioritize the themes. This audience chose “teamwork” as the most important theme of all the themes of Compassionate Connected Care for the Caregiver. While this is not a statistically valid study, clearly teamwork matters. We need professionals across the continuum of care to collaborate closely with one another, not just work alongside one another. One caregiver put it this way: “We engage in mutual relationships with patients, with families, and with colleagues, to foster physical and spiritual healing, while honoring human dignity, values, and beliefs.” In Chapter 6, we’ll discuss ways in which we can form and sustain teams in order to optimize both patient and caregiver care and engagement.

The emotional dimensions of teamwork are especially important. In order to display empathy and compassion to patients, caregivers must receive it as well. Colleagues and supervisors must model the behaviors, teaching and coaching empathically and also showing empathy and compassion to one another. When leaders demonstrate empathy with patients, colleagues, and subordinates, they model the behaviors that matter to the organization. I have worked with organizations whose leadership is convinced that they provide care with empathy and compassion. The organizations talk about their mission, vision, and values, and they provide exemplary clinical care. But these leaders cannot understand why their patient experience and engagement scores remain subpar.

When I talk to managers on the units and in the ambulatory practices, they know the right things to say. They perform rounds and can produce the rounding logs documenting that their staff is in the room. The leaders tell me that they round as well, with the logs to prove it. On these rounds, patients tell them that everything is “fine.” When I go with leaders on their rounds, they stand in the doorway to greet patients—they don’t sit with them. Often, they read a scripted group of yes-or-no questions. I like to call this “flyby” rounding. Leaders go through the motions of rounding but make no real connections with patients and glean no real information. Feeling trapped and put on the spot, patients provide information that they think the leader wants to hear so that they don’t get their caregivers “in trouble.” They’re afraid to give honest feedback, aware that caregivers watching the leader round would be put on the defensive to explain negative comments. Those caregivers in turn emulate the leaders’ rounding behaviors, becoming “flyby” rounders themselves. Leaders in this situation perform rounding as a “check the box” exercise. They haven’t demonstrated real empathy or compassion to either the patients or caregivers.

When caregivers don’t receive empathy or compassion from team members and leaders, they themselves become burned out or exhibit compassion fatigue. The term “compassion fatigue” was first coined to describe the phenomenon of secondary trauma from being bombarded by complex physical and emotional challenges on the job.13 Others have identified the antithesis of compassion fatigue, a phenomenon called “compassion satisfaction.” Caregivers who experience compassion satisfaction experience “attitudinal values such as absorption, vigour and dynamism” while undertaking work-related endeavors.14 Nurses who experience compassion satisfaction generally burn out less, possibly because such satisfaction helps them avoid feeling lonely, disenfranchised, marginalized, and bereft of meaning or purpose.

Besides compassion satisfaction, resilience might allow caregivers to decrease compassion fatigue and avoid burnout. It’s not that the stressors, distress, and suffering experienced on the job goes away. Rather, resilient caregivers can bounce back from these stressors because intrinsic and extrinsic motivators exist that continue to add to that person’s resilience bank. The caregivers in our qualitative study identified some of these motivators as “work-life balance,” with one telling us that that she “protects [her] own health and healing as a whole being of body, mind and spirit with as much enthusiasm and dexterity as [she gives] to others.” Another remarked, “Having quality downtime on days off, spent doing something the healthcare provider enjoys, which is important for the recharging of one’s batteries.”

In addition to discussing their own health, caregivers told us they needed more flexibility in scheduling as well as more work incentive choices to become more resilient. Many caregiver schedules reflect organizational and provider needs, not the hour-by-hour and day-to-day volume and acuity needs of the patients we serve. To build resilience, we must build schedules that assure that we put the right caregivers in the right roles for the right amount of time focused on the patients and their goals. Press Ganey is working with Kronos, a workforce management company, to marry time, attendance, and role data with caregiver and clinical data from NDNQI. Client organizations in our study will change caregiver schedules in order to understand how the schedules impact the nurse and patient experience. That analysis will help organizations identify scheduling changes capable of improving the experience of caregivers and patients.

A final theme we uncovered, one that underpins all the other themes of Compassionate Connected Care for the Caregiver, is communication. Teams work best when we break out of our silos to assure accurate, transparent, and meaningful dialogue among team members and between them and other teams. As research has shown, “Nurses who receive supportive communication from their peers and supervisors are more likely to experience lower rates of burnout.”15 They also feel better about their employers, so much so that they think twice about leaving to work elsewhere. Unfortunately, many factors impeded communication among healthcare professionals.

Michelle O’Daniel and Alan H. Rosenstein argue that communication and teamwork camaraderie are vital to effective healthcare outcomes. Common paths to better communication, they believe, include a “nonpunitive environment,” “shared responsibility for team success,” “clear and known decisionmaking procedures,” “regular and routine communication,” and access to necessary resources.16 Our study recipients identified behaviors along similar lines: “Listening to my patients and other staff members to understand their needs”; “Managers and coworkers listen and hear your worries and physical needs”; “Clear, direct, timely communication of clinical impressions and plans between all members of the team, to align our focus and messaging to OUR patient.” As our participants’ responses make clear, we need to attend to communication at all levels to improve resilience, engagement, and patient care.

Brandy’s Story Revisited

Remember Brandy, the thyroid cancer patient who had trouble advocating for her care? Imagine what might have happened had practitioners caring for her closely applied the Compassionate Connected Care model. Brandy’s PCP would have provided up-to-date, evidence-based clinical care driven not only by Brandy’s clinical signs and symptoms but also by her own concerns about bodily changes she had seen. The PCP would have assured Brandy that her team would continue to follow up and figure out what was happening. Brandy’s physician would have felt supported in practicing research- and evidence-based, zero-harm care. He would have communicated with his colleagues across disciplines and specialties, recognizing their expertise and asking questions without fear of being marginalized.

But that’s only the beginning—the clinical piece of Brandy’s care. As regards the operational dimension, Brandy would have only needed two primary care visits and would not have incurred at least three unnecessary visits. The provider, the insurer, and Brandy all would have saved money. The interprofessional team caring for Brandy would have sought opportunities to reduce waiting time for appointments and testing and would have communicated her results through an electronic health record portal as well as by phone. The members of the team would have had the resources available to reduce redundancy in their work and streamline processes, automating them whenever possible. The operations of the practice and the organization would have been optimized, so that when caregivers did the right thing for Brandy, they also would have been operating most smoothly and efficiently.

How might Brandy’s caregivers have behaved in her presence? Well, the PCP would have sat with her to discuss her care, listening to her concerns and taking 56 seconds to connect with her on a personal level, thus assuring that Brandy felt safe in his care. Members of the team would have narrated their care for Brandy, so that she would know what was happening at all times during her diagnostic testing and treatment. The team would have answered Brandy’s questions and asked for her to participate in decisions about her care. Team members would have ensured that Brandy’s husband also felt supported, answering his questions and involving him in her care as well. Finally, team members would have provided education and information to Brandy and her husband proactively, helping them to avoid feeling anxious.

As for the dimensions of connectivity and culture, the people caring for Brandy would have worked together as a true team, communicating transparently and appreciatively, eliminating silos, and sharing decision making. Each provider would have felt a part of something bigger than his or her individual efforts, and each would have felt that the organization supported him or her and that he or she had the resources needed to do a great job. Team members would have understood how their work aligned with the mission, vision, and values of the organization. A culture of safety would have existed that rewarded good catches and near misses, with teams conducting positive root cause analyses and appreciative inquiry to prompt questions and improve care delivery. That way, when Brandy questioned her diagnosis, treatment, and care, team members would have followed up with their colleagues in due course to address her concerns.

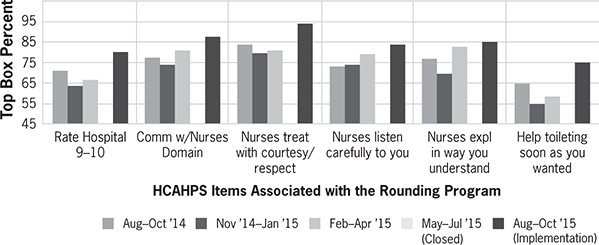

All of this sounds good, right? Maybe a little idealistic? I absolutely agree. Achieving care like this is anything but easy. And yet some organizations have taken the Compassionate Connected Care frameworks to heart, “owning” the concepts and achieving positive change in their organizations. At Conway Regional Medical Center (CRMC), a nonprofit, 154-bed acute care medical center located in Conway, Arkansas, caregivers and administrators felt frustrated by stagnant HCAHPS scores. Nothing they did seemed to push the scores higher in a sustainable way. Working with Press Ganey on a pilot basis using the Compassionate Connected Care framework, the members of a unit at the hospital selected a priority key driver change initiative—in their case, frequent patient rounds. They focused on embedding certain key driver behaviors into the entire organization.

To help with behavior change, the unit created broad and ongoing messaging explaining the need for change. The unit trained and engaged executive leaders to behave as sponsors of the initiative, and it trained unit leaders and staff on how to conduct patient-centric hourly rounds. To support caregivers, the unit emphasized coaching as well as positive, appreciative coaching techniques. The results were impressive. Patients rated the hospital higher, and they gave nurses higher scores for treating them with respect, for listening to them, for explaining aspects of their care to them, and for delivering prompt care. Patient experience improved, and suffering declined (see Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 HCAHPS rating by age and health

This unit worked comprehensively on improving a particular feature of the care it delivered. The initiative operated on multiple levels at once, addressing individual caregivers, the workings of teams, and organizational aspects. In the chapters that follow, we’ll examine in greater detail how you and your colleagues might apply the model on all these levels, and we’ll also look at how the healthcare industry as a whole might adapt Compassionate Connected Care. In the next chapter, we zoom in on the most basic level, the individual caregiver delivering care face-to-face with patients. Healthcare doesn’t get any more direct than this. As we’ll see, each of us as caregivers can take a series of steps on a daily basis to deliver care that is more compassionate and connected, both for patients and for the colleagues who support us.