CHAPTER

7

The Compassionate Connected Organization

THE YEAR WAS 2009, and Amy Cowperthwait, a veteran nurse and coordinator of the Skills and Simulation Lab at the University of Delaware’s School of Nursing, realized that her program needed to change. Like many other institutions, the university had trained young nurses by relying on electronic mannequins. Yet these mannequins weren’t preparing students very well for what they would encounter in their future work with live human patients. “It was impossible,” Cowperthwait recalls, “to cultivate simulations that focused on essential communication skills for healthcare providers”—skills like developing rapport, empathy, and therapeutic communication. The mannequins didn’t behave like human patients did.1 They were “unable to follow commands or express emotions in a way that was believable.” Although the mannequins could verbalize pain as well as emotions like sadness or anger, they couldn’t wince or make other facial gestures that evoke emotion.

On one occasion, Cowperthwait was running a code blue simulation that included postmortem care for the patient. After having nursing students identify that the “patient” had coded, Cowperthwait had them deliver several rounds of CPR, code drugs, and shock treatment. Addressing the students over a loudspeaker, Cowperthwait called the code and the time of death. What she saw next startled her. The nursing student who had been performing the final round of CPR “picked up her hands and slammed them down on the chest of the patient. ‘You’re dead,’ she shouted.” Then the student slapped her hands together to indicate that her work there was done. Cowperthwait was mortified. As she says, “I remember thinking that this patient would be someone’s father, someone’s brother, and that abusing a corpse is a federal offense!” At that moment, Cowperthwait realized that her students “weren’t equating the manikin with a human life. The manikins had no ability to provide the needed reference to humanity. If I’m being honest, it scared me a bit.”

Cowperthwait realized that she needed to inject more real human contact into the simulation program. But how? She got an idea: drama students. Collaborating with the university’s theater department, she helped create a program called “Healthcare Theatre” in which nursing students engaged in simulations on theater students who had been trained to behave like sick patients and family members. Immediately after the simulations, faculty members from the theater department directed the theater students and helped them develop feedback for the nursing students in the room.

Debuting in 2009, Healthcare Theatre was a rousing success. Over several years, it grew to become two fully approved university courses that were cross-listed in the theater and nursing departments. Students were incorporated into all nursing simulations run by the simulation lab, as well as into skill labs that did not include invasive procedures. According to Cowperthwait, nursing students benefited from “over 650 hours of quality simulation and patient-centered feedback each semester.” They learned to attend to the human dimensions of caring for patients, gaining experience that would help them to minimize suffering during their future work as nurses. The program was so successful that the School of Nursing featured Healthcare Theatre to help recruit top academic candidates. A number of university administrators likewise referenced Healthcare Theatre when highlighting the university’s interprofessional work. Healthcare Theatre has expanded to include physical therapy, medical anthropology, behavioral health, and nutrition programs at the University of Delaware. The course has also attracted undergraduate students from many other majors including psychology, engineering, communications, marketing, premed, biology, criminal justice, political science, exercise science, and medical laboratory sciences.

As the example of Healthcare Theatre suggests, the ability of healthcare organizations to deliver Compassionate Connected Care hinges on more than just the efforts of individual caregivers and localized teams. It requires that organizations engage to provide support, encouragement, and resources. Health systems, hospitals, ambulatory practices, long-term care facilities, and other organizations must educate present and future caregivers so that they truly understand how to meet the needs of patients and their families. But their obligations extend far beyond education. These organizations must create nurturing cultures that at once reduce suffering for caregivers and energize them to provide the best possible patient experiences. Without strong organizational support, caregivers and teams will feel hamstrung and ultimately defeated in their attempts to provide compassionate and connected care. The best care today—that which combines patient safety, clinical excellence, and excellence in the healthcare experience—occurs within organizations large and small that have dedicated themselves wholeheartedly to the mission of reducing suffering for everyone.

The Power of Culture

You might wonder: Do organizations really impact the amount of suffering patients and caregivers experience? Don’t individual caregivers and teams—the people who actually interact with patients and one another—have the most influence over experience in healthcare settings? Yes, individuals and teams are critical, but the evidence shows that organizational support—in particular, a strong organizational culture—matters a great deal. When the culture of an organization supports the processes of care provided by teams, caregivers feel more satisfied with their jobs, and the quality of patient care improves. Outcomes improve, even in facilities with complex and intense care requirements.2 The suffering of both patients and caregivers decreases.3 As the authors of one study have noted, organizational support impacts individual and team effectiveness, as they rely on “leadership, shared understanding of goals and individual roles, effective and frequent communication, … shared governance, and [empowerment] by the organization.”4 All these elements, of course, contribute to and help constitute organizational culture.

Conversely, organizations that don’t support teams with strong cultures of excellence see lower caregiver engagement and care quality, which correspond with increased suffering. When a general sense of diminished expectations pervades an organization, teams tend to communicate and collaborate poorly. Team members expect poor information, which as researchers have noted, “leads to errors because even conscientious professionals tend to ignore potential red flags and clinical discrepancies. They view these warning signals as indicators of routine repetitions of poor communication rather than unusual, worrisome indicators.”5

Unfortunately, many healthcare organizations lack dynamic cultures that promote and reward excellence in quality, safety, and patient experience. One culprit is industry consolidation. As hospitals and provider practices have acquired one another and merged, the resulting cultures have often suffered, becoming uneven and incoherent. CEOs at larger systems often make excuses for their cultures, claiming that “they’re different” from the industry-leading organizations because their patients are sicker or because they serve economically challenged areas that create staffing challenges. Although such challenges might exist, the fact is that efforts to integrate an array of smaller organizations, each with its own culture, policies, staff, and patient care practices, often fail. In addition, the very economic pressures that prompt healthcare organizations to consolidate have led to cost cutting and staff layoffs. In the best of circumstances, layoffs hit employee morale hard, but when organizations fail to communicate properly, employees become disengaged and disillusioned. The culture of the organization feels inadequate and unhelpful, if not outright hostile. Suffering increases.

The Importance of Leadership

If caregivers’ ability to reduce or mitigate suffering hinges on organizational culture, how might organizations build their cultures so as to implement the Compassionate Connected Care model most effectively? As with teams, leadership makes all the difference. No organization of any kind can build or sustain a high-performance culture, and realize the business results that accrue to such a culture, without leadership’s full support and attention. That holds especially true in healthcare. Researchers have investigated the organizational factors that exist in high-performing academic medical centers. As they’ve found, the leaders at these medical centers tended to work harder than most on personally affirming cultural standards of excellence. They focused on quality and safety during meetings, used leadership rounds to identify and address performance issues, perceived “excellence in service, quality, and safety as a source of strategic advantage,” and enlisted practitioners to improve areas like “timeliness, customer service, facility cleanliness, and safety.”6 In addition, CEOs at top-performing institutions were “passionate about improvement in quality, safety and service and had an authentic, hands on style.”7 They made their desire to serve patients clear to employees, including lower-level staff. In sum, these leaders shaped the cultures of their organizations by engaging everyone around treating patients well.

At lower-performing organizations, employees weren’t as clear about the organization’s dedication to patient care, teaching, and research. Leaders at these sites typically seemed satisfied with their organizations’ current quality and safety performance, despite data demonstrating quality and safety issues. Some of these leaders touted their organization’s scientific accomplishments as evidence of clinical quality, discounting data that showed subpar performance in quality or other areas. In general, leaders of lower-performing organizations didn’t make service excellence a high priority, viewing quality and safety as moral imperatives but not strategic business concerns. As a result, these organizations had lower HCAHPS scores, which as we’ve seen, translate into higher levels of patient and caregiver suffering. At these organizations, we may extrapolate that more patients felt unsafe, and more caregivers felt unappreciated.

This study and other research point to a number of specific areas on which leaders can focus to align organizational culture better with the Compassionate Connected Care model. Leaders must translate the organization’s core mission, vision, and values into tangible and tactical practices and processes for the people who care for patients every day. They must also focus on areas like transparency and safety. Let’s briefly review each of these areas in turn.

Articulate the Organization’s Mission, Vision, and Values

What exactly does an organization seek to accomplish? Why does it exist? Employees of any organization can’t work toward common objectives without understanding their organization’s common purpose or mission, and they certainly can’t do it passionately or energetically. A similar situation exists in healthcare organizations, and it relates directly to caregiver and patient suffering. If leaders don’t define a strong mission, caregivers become disengaged. As we’ve seen, this disengagement leads to corresponding declines in the quality of care, safety, and patient experience. Further, if leaders don’t define a patient-centered mission, the organization isn’t helping caregivers to focus on practices that will improve the patient experience. Patients again suffer, experiencing greater wait times, poorer communication, less frequent emotional connections with caregivers, and so on.

Research has confirmed a link between well-articulated organizational missions and employee engagement. In any organization, an important component of employee engagement is meaning. Employees must see their work as having an impact or serving a significant purpose. They must feel that they are contributing in their own limited sphere to the organization and its goals. Northwestern University graduate student Carrie Gibson studied individuals representing a variety of different industries, organizational departments, and lengths of employment to understand employee engagement. Her study, like those undertaken at Press Ganey, found a “strong positive correlation between organizational missions and the meaning of employee existence.”8 When organizations utilize missions, they provide employees with a strong sense of purpose, which in turn enhances “the meaningfulness condition of employee engagement.” People feel that they are worthwhile, valuable, and useful. They feel more energized to do their best. In healthcare settings, higher engagement again leads to better patient experience and reduced suffering.

If a mission constitutes an organization’s purpose, vision is, by one definition, “a mental image of a possible and desirable future state of the organization.”9 It’s where the organization is headed. Research performed with small professional services firms has found positive correlations between leaders who communicate visions well and financial performance, productivity, and retention.10 Other research has suggested that having a vision motivates employees to perform better, which in turn leads to performance results.11 In healthcare, as we’ve seen, when caregivers feel motivated and committed, engagement rises, leading to higher HCAHPS scores—resulting in less suffering for patients and caregivers. Communication of vision by leadership helps caregivers feel a stronger sense of belonging and shared purpose. Leaders who start every meeting by reminding team members how the meeting, policy, practice, or process flows from both the mission and the vision help caregivers connect their work with the organization’s shared purpose. Team members come to “own” the organization’s success or failure in a way they wouldn’t otherwise.

Leaders must take care to translate the vision into specific performance goals. As the management thinker Peter Drucker observed, service organizations (like those in healthcare) can’t improve performance and achieve desired results unless leaders execute their primary responsibilities, which include setting goals as well as defining the business, prioritizing, measuring performance, using the metrics for feedback, and auditing objectives and results.12 If an organization doesn’t clearly articulate its larger goals, it can’t reward people for helping to attain them or dock them if they don’t contribute. People don’t understand how to manage and improve their performance or contribute to the organization’s success. I’ve related how when I began my career as a staff nurse, my hospital had a plaque on the wall by the elevator that articulated its mission, vision, and values. However, it was only a plaque. I had no idea that the words it contained related to my work or to the hospital’s success. My manager and other leaders had to make that connection for my colleagues and me. They had to discuss specific goals in huddles and meetings, explaining how each line item in the budget, performance improvement project, capital budget expenditure, and hiring decisions tied back to the vision. To reduce suffering, we leaders need to specify clear goals and connect them to the guiding principle of bettering the patient and caregiver experience.

Beyond defining a clear sense of an organization’s mission and direction, leaders can help build a supportive culture for caregivers by defining and affirming the shared values that inform how work gets done. The values and the shared beliefs they reflect help underpin an organization’s “deep culture.” Research has shown “that clear organizational values improve employee morale,” in part because these values implicitly hold each person “to the same, value oriented obligations.”13 Employees also thrive on the feeling that the organization’s values mirror their own14—a finding that Press Ganey has confirmed specifically in connection with healthcare organizations. Employees feel more committed to their organizations and like their jobs better. They also feel more loyalty to their organizations and seem to experience less stress.15

To build a culture consistent with and supportive of Compassionate Connected Care, leaders must align the organization’s values with its mission and vision, and they must also assure that these values truly center on the patient. Of these two tasks, alignment might prove the trickiest. Even if physicians, nurses, administrators, and others agree to certain values, we all tend to look at those values differently. When I worked with the outspoken trauma surgeon mentioned in Chapter 6, he and I realized that we didn’t approach patient care in exactly the same way. As a physician who was responsible for his own group of patients, he advocated primarily on their behalf. I, however, bore responsibility for the care of all the unit’s patients and employees, as I was the unit manager. Further, when I was promoted to VP and administrator for large areas of the healthcare system, I bore responsibility for larger groups of patients and employees across the entire continuum of care. From my perspective, a singular focus on any one group of patients over others could prove detrimental—it was the bigger picture that counted. As a result, this surgeon and I diverged in how we interpreted and actualized our organization’s vision.

For instance, this surgeon might have respected the work of a given nurse on the unit and requested that she care for his patients whenever possible. As a manager, however, I might have known that this nurse would not always be able to care for his patients. Further, I might have known that having her attempt to care for his patients might interfere with her workflow. As a manager, I had to assure that we met the needs of all patients and staff, not just those of one surgeon. Neither this surgeon nor I was “right” or “wrong” in trying to live by our organization’s values. Our focus was just different.

This surgeon tended to focus on the short term because he was trying to meet his patients’ immediate needs. Most physicians and caregivers probably do this. Leaders of healthcare organizations, in contrast, should focus on positioning the entire organization for the future, serving the greater community, and assuring that the organization allocates limited resources effectively so that it can achieve its broader goals.16 Understanding these different perspectives helps foster empathy between leaders and caregivers, and allowing each colleague to articulate his or her perspective helps leaders and caregivers to arrive at better decisions. Once this surgeon and I understood the differences in how we perceived organizational values around patient care, we could tackle the problem in ways that spoke to each of our concerns. The result, in this case, was better scheduling practices for staff and patients—and ultimately, a better experience for all.

The implication here is that leaders should regard the articulation of values as an ongoing process of negotiation. As the leadership expert James Burns noted, guiding people in such a process is actually a defining quality of “transformational” leadership. “The essence of leadership in any polity,” he wrote, “is the recognition of real need, the uncovering and exploiting of contradictions among values and between values and practice, [and] the realigning of values… .” Leaders needed to help people to become more alert to their perspectives—“to feel their true needs so strongly, to define their values so meaningfully, that they can be moved to purposeful action.”17 Just as compassionate caregiving is about understanding and serving patients’ human needs, so we might describe compassionate and connected leadership as “clarifying human values and aligning them with the needs of the organization.”18 Put differently, there are many ways to “focus on the patient.” By ensuring that those perspectives all come to the surface, and by helping negotiate what “focus on the patient” ultimately means in each situation, leaders can help establish a strong and meaningful culture that galvanizes caregivers to reduce suffering.

Prioritize Safety

By attending to mission, vision, and values, leaders can align their organizational cultures behind the Compassionate Connected Care model. Yet they can take other actions as well to render their cultures more compassionate and connected. First, they can prioritize improving safety, quality, and patient experience and become a high-reliability organization (HRO).

According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, “high reliability organizations are organizations that operate in complex, high-hazard domains for extended periods without serious accidents or catastrophic failures.”19 Healthcare organizations have only recently begun to embed the notion of high reliability into their cultures, but this notion has long defined organizations in industries like aviation and nuclear power, where mistakes can cause catastrophic outcomes.

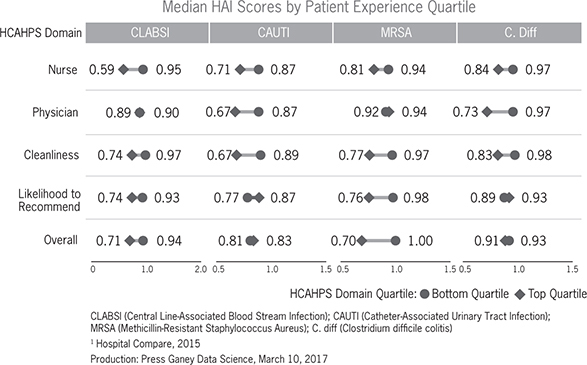

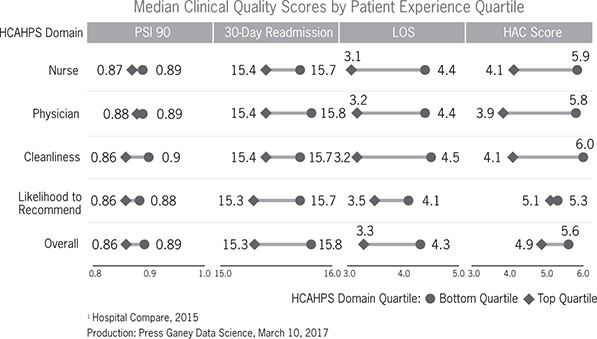

In healthcare, HROs embrace the culture of safety as their operating system and, as a result, experience higher staff engagement and better patient experience. Indeed, cross-domain analyses of the Press Ganey patient experience, engagement, and NDNQI databases suggest that the elements of safety, quality, experience of care, and caregiver engagement are all intimately interwoven with one another. Further, we’ve found that improving these three elements also leads organizations to improve their financial outcomes. Focusing on improving patient experience and lowering suffering can also yield safety gains. In our research, systems in the top quartile for HCAHPS patient experience metrics (those assessing interactions with nurses and physicians, as well as those evaluating cleanliness, likelihood to recommend, and the overall hospital rating) see lower rates of hospital-acquired conditions (see Figures 7.1 and 7.2). They also chart shorter lengths of stay and fewer readmissions than systems that perform in the bottom quartile for patient experience. Increasing safety and reducing suffering go hand in hand.

Figure 7.1 Clinical safety/quality versus patient experience, median HAI score by patient experience quartile

Figure 7.2 Clinical safety/quality versus patient experience, median clinical quality scores by patient experience quartile

Leaders can take a number of steps to build more concern for safety into the culture. As a 2017 Press Ganey white paper has recommended, leaders should identify safety as a top organizational priority. They should also create an environment that encourages individuals at all levels to report errors or close calls without fearing repercussions. As vulnerabilities become apparent, they should promote collaboration across ranks and departments to develop solutions. Finally, they should allocate sufficient resources to address safety concerns.20

Organizations that move aggressively to prioritize safety can make rapid progress. In 2012, Tennessee-based Community Health Systems (CHS) began a safety journey across all its 150 hospitals. CHS obtained certification as a patient safety organization (PSO) from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Subsequently, CHS formed another organization, CHS PSO, LLC, a component PSO of CHS that would be able to provide a secure and confidential environment for collecting and analyzing safety data from CHS’s hospitals. The objective: to identify and reduce or eliminate the risks and hazards associated with patient care. Meanwhile CHS took action to construct a high-reliability culture, drawing on the expertise of HPI/Press Ganey and deploying evidence-based tools. As we wrote in our white paper, “By consistently practicing proven safety behaviors and measuring serious safety events in a highly reliable way, determining their causes, and changing procedures to prevent their recurrence, the health system has reduced its serious safety event rate by nearly 80 percent.”21

Pursuing an HRO designation doesn’t just have to be about improving safety. Healthcare organizations moving to become HROs often seek to improve metrics in a number of areas, including quality, experience of care, caregiver engagement, and efficiency. In fact, some organizations are using the HRO concept to improve in all these areas at once. Whichever areas an organization wishes to enhance, it can use the HRO concept as a means of supporting the Compassionate Connected Care model. Clearly, improving safety will prompt an organization to break down silos and forge better connections between disciplines and between caregivers and patients. Likewise, HROs require compassion in order to function well. After all, improving safety means deferring to the expertise of colleagues throughout an organization. That, in turn, implies the prevalence of mutual respect—a cultural trait inculcated via humanistic and relationship-oriented leadership styles. Just as caregivers deploy relationship skills to treat patients compassionately, so leaders can to help entire organizations become more compassionate—and safer. Suffering will lessen in turn.

Improve Communication

As we’ve seen, poor communication among caregivers increases suffering. While teams and individuals can address that problem, leaders also can address it by embedding strong communication into the organization’s culture. Hospitals routinely encourage physicians and nurses to raise concerns whenever appropriate, but individuals lower down in the hierarchy often fear doing so.22 Their concerns go unexpressed, preventing organizations from identifying and remedying safety and patient experience issues and perpetuating those issues by causing individuals to become disengaged and disenchanted in their jobs. Leaders should implement comprehensive policies and strategies for listening to the concerns of employees, stakeholders, and community members. As the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) has noted, “Listening to employee issues and concerns builds loyalty and improved productivity. Organizational leaders can learn through listening about issues or concerns before they become formal grievances or lawsuits. They can also discover potential employee relations issues and learn about attitudes toward terms and conditions of employment.” To improve communication, SHRM advises that organizations link communication to their strategic plans—and specifically to their mission, vision, and values. They also suggest that organizations communicate consistently, seek input from all constituencies, and take steps to assure the organization’s credibility.23

As regards this last piece of advice, it’s especially important that healthcare organizations communicate transparently with stakeholders, especially patients. Consumers of healthcare have more information than ever before. They can visit websites like https://data.medicare.gov to compare hospitals on clinical quality, patient experience, and outcomes, and they can also go online to post their perceptions in far less scientific ways. Indeed, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association discovered that “59% of American adults find online ratings to be an important consideration when choosing a physician. Over one-third of those who used online reviews chose their doctor based on positive reviews, and 37% reported avoiding physicians with negative reviews.”24

Despite concerns about the reliability of online reviews, organizations have much to gain by promoting greater internal and external transparency about their data. Leading-edge organizations are already publishing their physicians’ quantitative and qualitative patient experience data on their own websites. They post every rating and comment, whether positive or not, attributing each one to the physician who delivered care. As a result, these organizations gain more control over the scientific validity of the data that appear online, and they ensure that patients get the most accurate picture possible of the quality of care these organizations have provided. Physicians gain more confidence in the data and tend to become more engaged in the organization’s improvement efforts.

Transparent communication through online reviews mitigates avoidable patient suffering by empowering patients to make the best choices they can for their care. Selecting a physician can prove challenging even for a healthy patient. For patients seeking care for illness or injury, it can cause a great deal of anxiety. Treating patient experience data in a transparent manner honors the right of patients to make informed decisions about care. For organizations, transparency is a proactive strategy for connecting with patients and treating them with compassion and empathy before they even make their first appointment.

To move toward greater transparency, organizations should expand the volume of data they collect about physician performance outcomes. It’s hard to be transparent if you don’t know how your caregivers are performing. Moreover, all patients deserve a voice in rating the care they have received. By surveying entire patient populations rather than just a random sample, organizations can tell a story about the care they provide that truly reflects the patient experience. They can further use the survey data to identify areas for improvement and to unleash an epidemic of empathy among providers. Physicians will embrace valid and reliable data that help them better understand how they are performing and where they might improve. Transparent communication of data also reduces patient suffering by engaging and enabling patients to collaborate actively in their own care.25

Enhance the Work Environment

Yet another way leaders can build organizational cultures that support Compassionate Connected Care is by enhancing the work environment. Some nurse leaders perceive staffing as the greatest challenge that prevents us from optimizing patient and caregiver experience, but that’s not exactly true. The work environment often plays a greater role. As a bedside nurse, I knew how good I felt when my manager voiced appreciation for my work, when my colleagues and I helped one another and agreed that we provided great care, and when I felt that I was paid a fair wage. I also know that I was more inclined to work an extra shift, take an extra patient, and cover for my colleagues’ breaks. My work environment helped enable me not only to provide compassionate and connected care for my patients but to maximize my own potential as a nurse and as an employee. The work environment enabled me to do what it took to reduce suffering for patients and my fellow caregivers.

The data bear out my experience. Although higher staffing levels are associated with more positive nurse perception, more positive patient experience, and fewer negative patient outcomes, cross-domain analytics demonstrate that the perceived status of nursing in the organization—a direct product and characteristic of the work environment—exercises a greater influence over caregiver experience.26 When nurses perceive that the organization has valued them sufficiently to provide them with enough supplies and staff training, to hire qualified and skilled nurses, and to take other steps to ensure nurse engagement and job satisfaction, their experience improves, and their degree of suffering declines—as does patient suffering. Further, organizations that empower nurses to enact professional nursing standards or best practices tend to see rises in the overall quality of performance and patient care.27 As the 2015 Press Ganey “Nursing Special Report” noted, “An organization’s own caregivers are uniquely qualified to comment on the quality of care delivered by the organization. The strong relationship between nurses’ assessment of quality and work environment creates further imperative for focusing on this foundational aspect of leadership.”28

Research shows that supportive work environments foster safety and quality of patient care by boosting how engaged nurses are with their jobs. Engaged nurses feel a sense of ownership and loyalty on the job. They dedicate themselves to creating a safe environment for patients and an effective and efficient working environment for their colleagues.29 The safety and quality of care rises in due course.30 Conversely, defects or dysfunction in the nursing work environment can lead to both minor disruptions and major systemic consequences, both of which lower engagement and, in turn, influence the quality, safety, cost, and patient experience of care. If you don’t get the work environment right, everyone suffers, including patients. In an era of high nurse turnover and vacancy, you also render the organization vulnerable to severe staffing shortages, which further increase patient and caregiver suffering.

Organizations that perform well on patient experience, caregiver engagement, and nurse-sensitive clinical quality will work hard to assure that caregivers feel safe in their practice and can care for patients in proactive ways. To improve in this area, leaders can pursue a number of strategies including safe patient handling and mobility (SPHM) based on the American Nurses Association’s safe patient handling and mobility standards.31 These standards provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring the safety of both patients and nurses. They include measures such as creating a culture of safety, establishing a sustainable SPHM program, implementing ergonomic design, installing proper SPHM equipment, and establishing a system for training to maintain competency. Other strategies include providing for adequate breaks during work shifts, avoiding extended work shifts, hiring more highly trained RNs (those with a bachelor’s degree or specialty certifications), and assigning nurses to patients in equitable ways.32

Since the same factors that help nurses feel safe and proactive in their caregiving are frequently those that help them to feel more engaged, leaders should build a culture of nursing excellence that supports all these objectives. Just as we try to provide compassionate and connected care to patients, so leaders should try to meet caregivers’ needs by acknowledging the complexity and importance of their work, providing the resources they need to do their jobs, promoting teamwork as a vital component for success, and removing barriers to a positive work-life balance.

Support Caregiver Education

To build cultures that support Compassionate Connected Care, there’s one more area in which leaders can and should focus: caregiver education. Given how unprepared many young caregivers are today and how potentially jaded some seasoned caregivers are, leaders must emphasize ongoing professional education and training if they are to have any hope of optimizing patient and caregiver experience. Innovative programs such as Amy Cowperthwait’s Healthcare Theatre, described at the beginning of this chapter, have an important role to play in training caregivers how to connect emotionally with patients. These programs do cost money: Healthcare Theatre’s projected budget for 2015 was about $110,000. Still, any investments that organizations might make in such programs yield important returns. When comparing costs and potential benefits, leaders should remember that direct caregivers constitute the largest line item on any healthcare organization’s operational budget. As such, they have the greatest impact on patient experience and the organization’s ability to achieve high safety and quality metrics. With a considerable portion of reimbursement pegged to patient and caregiver experience and safety, organizations stand to lose hundreds of thousands of dollars if caregivers don’t perform well in these areas. A small investment in teaching the art of connecting makes clear financial sense.

Healthcare Theatre is hardly the only innovative way to help caregivers understand the patient experience. Northwell in New York has created simulation labs that take caregivers through an exercise of both “being a patient” and acting as a caregiver. Renown Health in Reno, Nevada, has implemented a fairly unique orientation exercise in its emergency department to help foster empathy and compassion for patients. On their first day on the job, all new employees, no matter who they are or what their roles are in the emergency department, are asked to place all their belongings in a locker. They are then taken, without explanation, to the waiting room and left there for four hours, with no communication during this period. Then they are brought to a treatment room and the curtain is drawn. The new employees can hear all the ambient noise, and they can also hear other staff members talking about them. Again, no explanation is provided until the end of the day. At that time, the preceptor pulls aside the curtain and says, “This is what your patients go through every day. Don’t forget it.”

As I know firsthand, the experience of being a patient or a family member of a patient changes a caregiver’s perspective. Renown Health engineered a way for caregivers to begin to experience this shift in perspective without actually being a patient. How might your organization help caregivers better understand and connect with patients’ points of view? As the example of Renown Health suggests, a little imagination in this area goes a long way.

Mobilizing the Organization—and the Industry

During her time in Healthcare Theatre, a junior nursing student at the University of Delaware named Annie Gardner had a chance to portray a number of patients, including a diabetic teenager, a patient with cerebral palsy, an adult woman from the Appalachian Mountains with hypertension, and a depressed college student. As Gardner reflected, “Playing all of these different patients [opened] my eyes to different thought processes people have, why they say the things they do, and where people come from.”33 But the chance to interact with nurses during the role-play sessions also opened her up to the different ways that caregivers can treat patients. “After several interactions, it became clear who the ‘good’ nurses were; not because they did all the techniques right or they knew all the side effects to the medication I was prescribed, but because they made me feel like a person and not a patient.”

We desperately need more “good” nurses. But as we’ve seen in this chapter, caregivers and teams can’t make real progress in reducing suffering unless healthcare organizations themselves take this goal as their guiding principle. Leaders must believe passionately in the need to reduce suffering, and they must dedicate themselves to building cultures that are compassionate and connected. They can do this by articulating a clear mission and vision for the organization as well as clear values. But that is only the beginning. Leaders must also attend to a number of other factors that bear on culture, including safety, communication, workplace experience, and education. Combine these elements together, and you arrive at a culture and an organization that is fully mobilized around enhancing patient and caregiver experience. Impressive reductions in suffering will follow.

The Compassionate Connected Care framework transports us to the intersection of clinical excellence, operational efficiency, caring behaviors, and culture. Organizational leadership and structure must influence and drive these components. But is the healthcare industry itself ready to optimize care for patients and caregivers? In the next chapter, we examine the history of healthcare reform and what we must do as an industry to make compassionate and connected care the norm, rather than the exception it largely is today.