|

8 |

IT Security Policy Framework Approaches |

AN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY (IT) security policy framework supports business objectives and legal obligations. It also promotes an organization’s core values. It defines how an organization identifies, manages, and disposes of risk. A core objective of a security framework is to establish a strong control mindset, which creates an organization’s risk culture.

So selecting the right information security framework is important. There are a variety of frameworks in industry to choose from. A number of these are industry specific. Others offer a comprehensive view of IT that cuts across all industries. Which one is right for your organization will depend on the organization’s needs, the employees’ experience, and the regulators that have jurisdiction.

Regulators will have an interest in how the organization’s leadership manages risk. One way to demonstrate this is to adopt and effectively execute security policy frameworks. Additionally, selecting frameworks that are common within your industry increases the likelihood of success by allowing your organization to share experiences and incorporate learning from across the industry.

You can look at a security framework as a systematic way to identify, mitigate, and reduce these risks. The data can be at rest or moving through a process. In this context, risk represents an event that could affect the completion of these processes. For an organization truly to have control over these risks, a strong system of internal security controls must be in place. Everyone in the organization should understand and adhere to its security policies. These security policies and controls must extend beyond the IT department and into the business process.

The framework manages risk at an enterprise level. It helps an organization deal with conflicting priorities, resource constraints, and uncertainty. An effective IT security policy framework also enables management to deliver value to the business.

This chapter reviews various security policy frameworks. It discusses policy strengths and their positioning in the market. Additionally, the chapter examines key elements from the frameworks such as roles, responsibilities, separation of duties, governance, and compliance.

Chapter 8 Topics

This chapter covers the following topics and concepts:

• How to choose an IT security policy framework

• How to set roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities for personnel

• Why separation of duties within an organization is important

• What a structured approach to security policy governance and compliance entails

• What best practices for IT security policy framework approaches are

• What some case studies and examples of IT security policy framework approaches are

Chapter 8 Goals

When you complete this chapter, you will be able to:

• Compare and contrast multiple frameworks

• Identify the top security policy frameworks

• Understand the type of roles needed to support these frameworks

• Explain the responsibilities of these roles

• Describe how roles create a separation of duties

• Describe how roles create a layered approach to security

• Understand the need and importance of governance and compliance

• Understand how these frameworks are applied in the real world through case studies

IT Security Policy Framework Approaches

How do you choose among the many IT security policy frameworks promoted by government agencies, corporations, and many others? There’s no simple answer. Your choice will depend on your industry, as well as your management view of risk and any bias within your organization. You should focus on selecting the standards that are widely accepted.

No security framework can prevent all security breaches. At some point, a security event will happen. It could be as simple as someone sharing a password with someone else, or loaning a security badge to a colleague to provide (unauthorized) access to a restricted data center. Or it could be a hacker stealing customer data. Whatever the security event, an assessment of why the breach occurred and what controls failed should be conducted. Depending on the severity of the security event, regulators may be asking for answers. Adopting the right security policy framework helps demonstrate to regulators that your organization followed industry norms. Equally important, the effective adoption of a security framework demonstrates that when a security event occurs, the organization can effectively respond to minimize impact to the customers and shareholders.

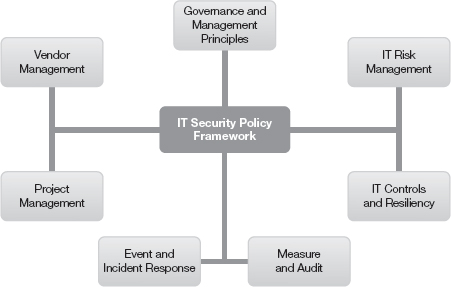

Figure 8-1 depicts a simplified framework domain model. Notice that a significant portion is dedicated to the governance and management of risks. This establishes the principle that managing risk and understanding business is a core competency. More comprehensive frameworks recognize that the effectiveness of controls rely on the understanding of the business process. Understanding the business process allows you to better identify risks and design effective controls.

FIGURE 8-1

Simplified IT security policy framework domain model.

Your first step is to determine the scope of coverage for your framework. Then, you can use it as a filter to make sense of the various frameworks to choose from. Even a simplified framework domain model can help you recognize your organization’s key areas of concern. You can create a framework that addresses specific weaknesses and aligns to your business requirements. Once you understand those requirements, you can use the following steps to select industry frameworks to consider:

1. Review industry regulatory requirements. For example, a government agency is required to implement the Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA).

2. Look to your auditors and regulators for guidance. For example, major external audit firms may have adopted Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) and Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT) as part of their controls testing.

3. Select frameworks that have maintained broad support in the industry over time. These are the frameworks that could be considered industry best practices.

Find out which frameworks are used by peer organizations. This can validate your approach. Many industries tend to share the same risk and leverage the same frameworks. Table 8-1 is a sample of IT security policy frameworks. These frameworks that are commonly adopted across an industry define the best practices of an organization. Best practices are typically the common practices and the professional care expected for an industry. This is not a comprehensive list, as there are other heavily used frameworks, including industry-specific frameworks. The frameworks in Table 8-1 represent different widely adopted framework approaches.

Even the short list of IT security policy frameworks shown in Table 8-1 provides a wide array of approaches and choices. Organizations often combine these frameworks to draw upon each of their strengths.

For example, a single organization could adopt the following:

• COSO for financial controls and enterprise risk management structure

• COBIT for IT controls, governance, and risk management

• ITIL for IT services management

• PCI DSS for processing credit cards

• ISO for broad IT daily operations

The combination of frameworks in this example provides a comprehensive view of business risk and information security. The combination would represent an organization’s security and risk framework. It starts with COSO, which provides a strategic and financial view of risk. COBIT links business requirements with technology controls. ITIL provides best practices for delivery of IT services. PCI DSS provides highly specific technology requirements for handling cardholder data. You could also substitute ISO for any of these layers or mix and match other frameworks to create a comprehensive policy approach.

TABLE 8-1 Sample of IT security policy frameworks.

Let’s compare and contrast COBIT and ISO. While these frameworks may overlap in the topics they cover, they differ greatly on the approach. COBIT will cover broad IT management topics and specify which security controls and management need to be in place. However, COBIT is often silent on how to implement specific controls. ISO, on the other hand goes into more detail on how to implement controls but is less specific about the broader IT management over the controls. In this way, both frameworks complement each other. As a result, many organizations adopt both.

The power of the frameworks in Table 8-1 is their flexibility and modularity. They are flexible in that they can align with each other or be implemented by themselves. They are modular in that you can pick and choose the component or set of objectives you wish to implement. An exception to this rule is PCI DSS. An organization required to adhere to PCI DSS must implement all of its requirements.

Risk Management and Compliance Approach

To deliver value, a framework must manage and dispose of risk daily. You will often hear the term disposal of risk. Once a risk is identified, you must decide what to do about it; you must decide how to “dispose” of it. This could mean either adding a control so risk no longer exists, or accepting the risk. When you accept a risk, it doesn’t mean you ignore it. Typically, if you accept the risk, you would consider the need to monitor for it and to create a detective control. In that way, when it does occur, you can detect it and take measures to minimize its impact.

For example, suppose you are concerned about malware. Changing a firewall rule to stop individuals from browsing the Internet would reduce the likelihood of malware. This would be unpopular with employees. Beyond that, though, Internet access may be essential for the business to operate. So you do your best to prevent as much malware as possible by installing appropriate software on the network and endpoint. Where you cannot prevent a risk, you monitor for suspicious traffic and respond as needed. In essence, you accept that no software can prevent every possible malware attack.

Although the previously mentioned frameworks all have unique approaches, they share some of the same characteristics:

• They are risk-based

• They speak to the organization’s risk appetite

• They deal with operation disruption and losses

The risk appetite refers to understanding the level of risk-taking within the business. This approach understands the business and its processes and goals. It’s the overall risk the organization is willing to accept. A key measurement is the cost of risk mitigation. The risk appetite is driven by the amount of risk reduction the business is willing to fund.

The goal of these frameworks is to reduce operation disruption and losses. The frameworks reduce surprises. They ensure risks are systematically identified and reduced, eliminated, or accepted.

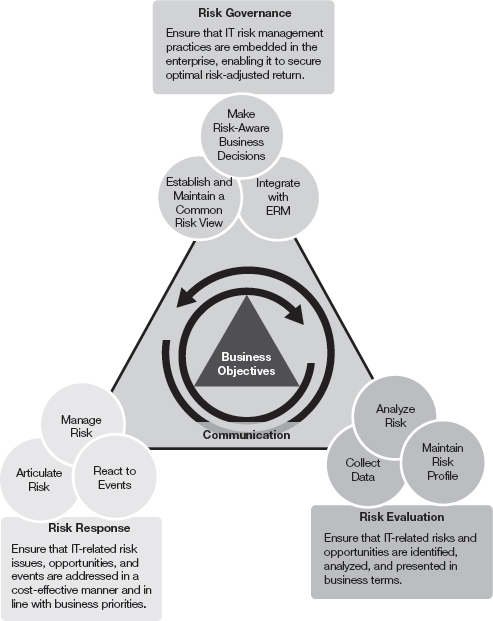

The ISACA Risk IT framework extends COBIT and is a good example of a comprehensive risk management approach. You can implement the ISACA Risk IT framework alone or as part of a COBIT implementation. Figure 8-2 is an overview of the Risk IT process model. The Risk IT framework is built on three domains: Risk Governance, Risk Evaluation, and Risk Response. Each of these domains has three process goals. Each process goal is broken down into key activities. For this discussion, this section will focus on domains and process goals.

The Risk Governance domain provides the business view and context for a risk evaluation. This ensures that risk activity aligns with the business goals, objectives, and tolerances. This includes aligning to business strategy. This domain ensures that the full range of opportunities and consequences are considered.

The Risk Evaluation domain ensures that technology risks are identified and presented to leadership in business terms. Formal risks are analyzed and processes are created to assess impact. This domain also creates a risk repository of all known risks. This further enhances the risk analysis and reporting.

The Risk Response domain ensures risks are reduced and remediated in the most cost-effective manner. This domain coordinates risk responses so that the right people are engaged at the right time. This prevents risks from increasing in magnitude. Processes are established to manage risk throughout the enterprise to an acceptable level.

FIGURE 8-2

The Risk IT framework process model is built on three domains.

These domains build on each other, creating flexibility and agility. You can discover a potential threat in the Risk Evaluation domain and quickly assess its impact using the Risk Governance domain. In addition, the framework can quickly identify and coordinate a response to any risk.

The Physical Domains of IT Responsibility Approach

When implementing an IT security policy framework, remember to align the framework to the business process. For example, ISO 27002 provides clear guidance and best practice recommendations on controls. This creates a clear linkage between the control and the business process. This allows you to see all the controls implemented to protect an end-to-end business process. This approach minimizes controls and prevents “silo” thinking about threats. Organizations use the frameworks to reduce costs and to meet regulatory compliance.

For example, assume you are assessing backup and recovery processes. If you follow the process, you can identify risks during the hand-off between technologies. Perhaps you can no longer restore a tape that’s been archived for several years. The backup technology in your data center was upgraded to a different format. Taking a look at the off-site inventory independent of the recovery aspect might miss this risk. Mapping out the process that controls the life of a backup tape is a better way to look at controls. A simple mapping might follow the tape from creation, transport, off-site storage, recall, recovery, and destruction.

Roles, Responsibilities, and Accountability for Personnel

It’s important to understand the relationship between individuals and organizational roles and committees. Many IT processes pass through numerous hands. Sometimes it’s through a committee or a group of individuals. For example, an organization may have a governance or management oversight to review major projects that have significant budgets. The difference between governance and management oversight is an important distinction. Governance oversight approves the controls and approach by which risk is to be managed. Management oversight executes within the rules set by the governance body. For example, a governance committee may say all projects costing more than $50,000 must be reviewed and approved by the chief information officer and the IT senior leadership team (SLT). It’s then up to the CIO to ensure that management processes follow the governance rules. This could mean having the project team present the proposed project in an SLT meeting and getting a formal vote of approval.

The Seven Domains of a Typical IT Infrastructure

Managing access to data can be a complex issue. Data can be in e-mails, in a word-processing document, or on a file server; or it can be accessed through a product application. Regardless, data must be understood and protected. Within the seven domains of a typical IT infrastructure are special roles responsible for data quality and handling. The following individuals work with the security teams to ensure data protection and quality:

• Head of information management

• Data stewards

• Data custodians

• Data administrators

• Data security administrators

The head of information management role is the single point of contact responsible for data quality within the enterprise. This person deals with all aspects of information. This person establishes guidance on data handling and works closely with the business to understand how information drives profitability. A business person as opposed to a technologist typically fills this role.

Data stewards are the individuals responsible for ensuring data quality within the business unit. Data stewards are the owners of the data. They approve access. They work closely with information management to ensure the business gets maximum value from the data. They define the business requirements for data and create descriptions of what the data is and how it will be used.

Data custodians are individuals in IT responsible for maintaining the quality of data. These individuals make decisions on how the data is to be handled given the requirements from the data steward. Whereas the data steward’s primary role is to design and plan, the custodian’s primary role is implementation.

Data administrators are responsible for executing the policies and procedures such as backup, versioning, uploading, downloading, and database administration.

Data security administrators have a highly restricted role. They grant access rights and assess threats to the information assurance (IA) program.

Organizational Structure

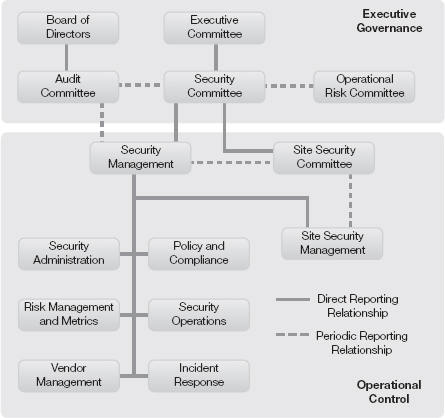

An organizational structure can tell you a lot about how risk is managed. It defines priorities through the teams’ specialties. It defines how the organization perceives its threats. It also indicates how agile the response might be. Figure 8-3 defines a theoretical information security organization in the private sector. Notice the layer of executive governance of the security function in this example. Executive governance provides oversight for the security process and authority to execute.

The board of directors establishes an audit committee to deal with audit issues and non-financial risks. The chief information officer (CIO) reports to the audit committee about technology issues. The chief information security officer (CISO) may also report issues directly to the audit committee. Alternatively, the CISO may report to the CIO. Then the CIO’s role is to report the security issues. The CISO may have a legal requirement to report to the board directly. For example, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) requires reporting to the board on the status of the GLBA program. That report is created and presented to the audit committee by the CISO. Keep in mind that the board of directors creates the audit committee. Consequently, issues on security coming to the board would generally go through the audit committee.

The executive committee helps set priorities, removes roadblocks, secures funding, and acts as a source of authority. The security committee members are leaders across the organization. This combination ensures buy-in from the business for the information security program. This is typically where a balance is reached between the needs of the business and the needs of the enterprise to implement effective security controls. So it’s important that the line of business (LOB) senior leadership be represented. The higher the level of LOB representation in the committee, the higher the committee’s perceived authority. The CISO is usually the chairperson. The CISO sets the committee agenda and facilitates discussions. The security committee reports its issues and budget requests to the executive committee. The executive committee aligns the security committee with the organization’s goals and objectives.

The security committee may have a less formal relationship with the audit committee and the operational risk committee. The committees will exchange information and on occasion agree to joint initiatives. Although less formal, these are key relationships. For example, the operational risk committee provides important information on the risk appetite of the organization. Knowing the risk appetite can help the security committee understand business requirements and priorities at an operational level.

Conversely, the risk committee needs to understand the information security capability and emerging risks. In this way, the risk committee can determine which business activities are riskier than others. Consider a business that wants to sell product on the Internet for the first time. The risk committee needs to understand the broad risks associated with this type of activity and, broadly, the organization’s security capability.

The security management role is held by the CISO. The security committee is the key committee for the CISO. This is where the CISO can set the agenda and direction of the security and risk program.

Security administration in Figure 8-3 refers to centralized access management. Centralized access management refers to creating and maintaining user IDs, which includes granting users access rights. This also includes building roles and ensuring appropriate levels of segregation of duties. The team most likely works with project managers and developers to ensure application security requirements are met. Depending on the volume of projects, this function could be separated from security policy management.

The policy and compliance team is responsible for creating, reviewing, approving, and enforcing policy. This team works with legal to capture policy regulatory requirements. The policy and compliance team provides interpretation of policies. They approve deviations from policies. This team interfaces with regulators, providing evidence of compliance. The team monitors the effectiveness and adherence to policies.

The risk management and metrics team reviews the business processes and identifies potential risks and threats. The team works closely with the business to understand potential for fraud. Team members communicate with the other security teams to provide them with their assessment and analysis. They similarly use the other security teams as a source for metrics. By combining various metrics, they develop a scorecard that indicates key risks and the effectiveness of the security function. They also create reports for the CISO to present to various leaders.

A security operations team monitors for intrusions and breaches. Team members monitor firewalls and network traffic. When a breach is discovered, they activate the incident response team (IRT). The IRT responds to breaches and helps the business recover. Furthermore, the IRT assesses how the breach occurred and makes recommendations for improvement. The IRT performs forensic examinations, investigations, and interfaces with law enforcement agencies.

The vendor management team manages security concerns with vendors and third parties. Before data leaves the organization and is processed by a third party, this team would have performed an assessment on that vendor. Some organizations have adopted the concept of permission to send. In other words, data is not allowed to leave the organization until it’s been verified that the vendor’s control environment meets the organization’s own requirements. Only then will permission to send be granted.

Figure 8-3 is a theoretical model based on combining a number of the best practices frameworks. This hybrid organizational structure illustrates the need for support from leadership and business. The number of teams and specialization depends on volume of activity, complexity of environment, and funding. The key point is that these teams do not operate in isolation. An organizational framework creates specialties that have the agility to respond quickly, while continuously working to reduce risk to the business.

Organizational Culture

The organizational culture influences how IT security policies are implemented. It starts with the tone at top—how senior leaders deal with the CISO. Security professionals are skilled in gathering threat information and analyzing the impact to the organization. They are skilled at identifying threats and vulnerabilities and then presenting these findings.

These are important and difficult skills to master. Equally important is the ability to navigate the organizational culture. These soft skills are especially important for a CISO. The CISO must connect and build trust with the business. Without building trust, the IT security team may be viewed as overhead rather than a partner in reducing risk.

As a security professional, you must not talk strictly in threat terms. You must have the ability to connect with LOB leaders and talk about threats in terms of risk to the business. For example, it’s more effective to talk about how malware could prevent the service desk from helping a customer than to talk about the technical way in which malware can infect a machine.

Successfully dealing with the organization’s culture means understanding how to drive value to the business. This means working with the business to draft comprehensive security strategies to increase the business’s capability. For example, the business may strive to be a virtual organization with extensive remote access. This means working on how to extend the perimeter to remote laptops versus focusing on why the risks for such a plan could be too high.

The key point is not to be out of step with the organizational culture. You must drive security solutions into the organization in a way that will resonate and be perceived as delivering value to the business.

Separation of Duties

A fundamental component of internal control is the separation of duties (SOD) for high-risk transactions. The underlying SOD concept is that no individual should be able to execute a high-risk transaction, conceal errors, or commit fraud in the normal course of their duties. You can apply SOD at either a transactional or organizational level.

Layered Security Approach

The layered security approach, which means having two or more layers of independent controls to reduce risk, can be a SOD. Layered security leverages the redundancy of the layers so if one layer fails to catch the risk or threat, the next layer should. By this logic, more layers should mean better risk reduction. However, more layers can be burdensome and expensive. There needs to be a balance between cost and return in risk reduction.

The classic example of an SOD is when it’s applied at the transactional level. If you have a high-risk transaction, or combination of transactions, then you want to separate them between two or more individuals. For example, suppose a business sets up vendor accounts and issues checks based on the goods received. That business has three distinct processes: setting up a vendor account, receiving goods, and paying the vendor. Having one individual control all three processes may prove too big a temptation for fraud. Such people could set themselves up as vendors and issue checks based on goods never received as one example. This type of fraud is reduced by assigning responsibility for these processes to separate roles.

Domain of Responsibility and Accountability

Typically, SOD applies to transactions within a domain. It’s management’s responsibility within a domain to identify high-risk transactions and ensure adequate SOD. Ensuring adequate SOD means that you identify opportunity for fraud within these transactions. It also means identifying the potential for human error within these transactions. Applying SOD can reduce both fraud and human errors.

The concept of SOD can also be applied across domains at an organizational level. Some organizational processes and functions come with risk. For example, ensuring an organization is compliant with regulations is vital and a high risk. As in the previous transaction example, you would not have one team responsible for all three tasks of designing, implementing, and validating solutions that ensure compliance. Typically, you create an organizational SOD between those teams that implement and validate compliance. Implementing an organizational SOD is less about fraud and more about reducing potential errors in vital processes and functions.

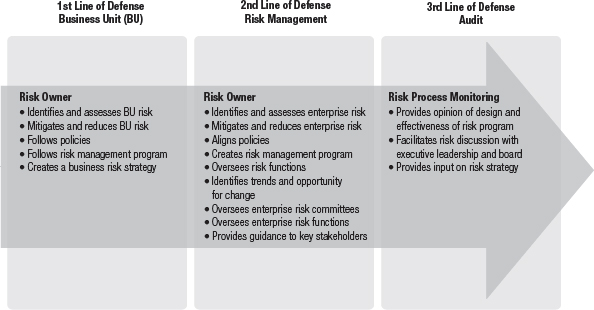

In the financial services sector, some organizations have adopted a three-lines-of-defense model. This risk management model is a good illustration of an organizational layered approach that creates a separation of duties. Figure 8-4 depicts a three-lines-of-defense model to risk management.

First Line of Defense

The first line of defense is the business unit (BU). The business deals with controlling risk daily. They identify risk, assess the impact, and mitigate the risk whenever possible. The business is expected to follow policies and implement the enterprise risk management program. The BU owns the risk and develops short-term and long-term strategies. Ownership means they are directly accountable to ensure the risk is mitigated or reduced.

The second line of defense is the enterprise risk management program. The risk management program can be made of multiple control partners (CPs), depending on the size and complexity of the organization. Operational risk management personnel and compliance personnel are examples of CPs. They are responsible for managing risk across the enterprise. They align controls and policies to ensure that the risk management program aligns with company goals. There is oversight of risk management across multiple risk committees and through various channels of risk reporting to stakeholders.

The second line is responsible for engaging the business to develop a risk strategy and gauging the risk appetite of the organization. Participants have an obligation to report to the board material noncompliance and risks that put the organization’s strategic goals in jeopardy.

Third Line of Defense

The third line of defense is the independent auditor. That role provides the board and executive management independent assurance that the risk function is designed and working well. Additionally, the auditor acts as an advisor to the first and second lines of defense in risk matters. The third line must keep his or her independence but also have input on risk strategies and direction.

Several views exist on how closely involved the third line of defense can be in advising leadership without losing independence. If the third line of defense advises a course of action, is he or she the right person to determine the success of that action? Many audit organizations develop rules to avoid this conflict. Views differ on whether external auditors belong in the third line of defense or actually compose a fourth line.

This model clearly demonstrates how organizational roles can be used to create a separation of duties. In this case there is oversight, checks, and re-checks across three layers of the organization. In an ideal world, the first line of defense would self-assess and identify all the risks. It’s not realistic to expect such precision. The basic idea is that what’s not caught in the first line is caught in the second line. What the first and second lines do not catch, the third line catches. By the time you reach the third line, whatever risks still exist should not be significant and are therefore manageable.

Governance and Compliance

Even in the best of situations, an organization can be challenged to provide evidence that policies are implemented, enforced, and working as designed. The process includes collecting, testing, and reporting evidence. This can be tiresome and time consuming, especially when an organization struggles to address what may seem to be endless audit findings. These audits can lead to retesting and more control deficiencies and risks identified.

Implementing a governance framework can allow the organization to identify and mitigate risks in an orderly fashion. Once in place, the ability to quickly respond to audit requests drastically improves. The framework provides the ability to measure risk in a few ways:

• In context of how well the organization has implemented leading practices

• In context of how much of the organization’s risk is covered by the resulting implemented controls

A well-defined governance and compliance framework provides a structured approach. It provides a common language. It is also a best-practice model for organizations of all shapes and sizes. A well-recognized framework standard provides a solid ground for discussing risk. It’s a foundation from which information security policies can be governed.

IT Security Controls

Regulatory compliance is a significant undertaking for a number of organizations. Some organizations have full-time teams dedicated to collecting, reviewing, and reporting to show adherence to regulations. This diverts resources that could have been applied to protect the business.

The IT policies framework helps reduce this cost by defining security controls in a way that clearly aligns with policies and regulatory compliance. The better an organization can inventory and map its controls to policies and regulation, the lower its costs to demonstrate compliance.

From a controls design view, best practices frameworks provide the mapping to major regulations such as the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) Act. As a result, the adoption of these frameworks is a quick way to demonstrate adequate coverage of regulatory IT requirements.

However, good design and effective coverage of regulatory requirements does not mean the controls are working. The more an organization can automate, the lower the cost to demonstrate compliance. This is because automation reduces the time to gather documentation, test controls, and gather evidence. Two key areas of automation are documentation and testing.

Automating documentation for IT security controls simply means capturing the policy and regulatory requirements at the time the control was designed and implemented. The level of automation does not require sophistication. The core requirement of the automation is that the information is searchable. Documenting the information in multiple places in a format that cannot be searched is not automation. When the information is centralized and searchable, it’s much easier to explain to a regulator how the organization is compliant. The ability to search a list of controls also makes it easier to determine which controls need to be tested. There’s a vast array of low-cost documentation library solutions that can be used for this purpose.

Automating the testing of IT controls is harder but yields the greatest benefit. The type and level of automation will depend on the technology, the control, and the complexity of the IT environment. For example, many tools can compare a file of active employees from an HR database to a list of active accounts. If the control to remove an individual is working, you should not see former employees with active accounts. Providing the same level of assurance manually would be far more costly and prone to errors. Manual verification in a larger population of users would be statistically based. You couldn’t check every account manually. You would instead sample past and current employees. Depending on the number of errors an auditor found, an opinion would be made as to the overall population of active accounts.

Automated testing tools are often shared across the enterprise to improve operational effectiveness. For example, assume the automated testing of a control identifies a defect. The defect is reported and fixed. During the next test, another defect is found, reported, and fixed. The cycle continues. The individuals responsible for security control often adopt the testing tool to validate their own controls. In the real world, these individuals are very motivated to avoid repeated audit findings. As a result, automation of compliance tests builds collaboration and improves operational effectiveness.

Testing for compliance is more complex than the few simple examples provided. Although the complexity and volume is much larger, the key concepts are the same. It’s the complexity of the technology and infrastructure that prevents wide-scale automated compliance testing today. Not all controls can be tested automatically. However, the goal should be to design controls that can be tested with automated tools.

IT Security Policy Framework

Business requirements lead to controls, which lead to reduced risk. Regardless of framework, the core objective of reducing risk remains the same. The frameworks listed in Table 8-1 can address many business risks. There are many other types of non-technology risks, well beyond the scope of these frameworks, such as credit or market risks. These are risks associated with customers being unable to pay, or market changes in which there’s no longer a demand for the product or service.

Business risks are defined as six specific risks, as follows:

• Strategic—Strategic risks are a broad category focused on an event that may change how the organization operates. Some examples might be a merger or acquisition, a change in the industry, or change in the customer. The key point is that it’s an event that effects the entire organization.

• Compliance—Compliance risks relate to the impact to the business of failing to comply with legal obligations. Noncompliance can be willful, or it can result from being unaware of local legal requirements. This could include regulatory requirements or legally binding contracts. Let’s say a company accepts the rules associated with processing credit cards but fails to implement PCI DSS. The card companies, under a binding contract, can force the merchant to stop taking credit cards.

• Financial—Financial risk is the potential impact when the business fails to have adequate liquidity to meet its obligations. This is when you fail to have adequate cash flow. For example, the consequences of failure to pay loans, payroll, and taxes would be financial risks. This lack of available funds can be due to a poor credit rating or operations too risky for banks to fund. Regardless of the reason, if you were unable to meet your financial obligations, that would be a financial risk.

• Operational—Operational risks are a broad category that describes any event that disrupts the organization’s daily activities. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) defines operational risk as “the risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems, or from external events.”1 In technology terms, it’s an interruption of the technology that affects the business process. That could be a coding error, slow network, system outage, or security breach.

• Reputational—A reputational risk results from negative publicity regarding an organization’s practices. This type of risk could lead to a loss of revenue or to litigation.

• Other—Other risks is a broad category of non-IT-specific events that introduce risk to the LOB. Typically, this category of risk relates to events that are outside the organization’s control. For example, political unrest could occur in another country where the organization has a call center. The political unrest is a non-IT event. Lack of personnel showing up for work could impact IT operations.

Best Practices for IT Security Policy Framework Approaches

Governance, risk management, and compliance (GRC) is the discipline that systematically manages risk and policy compliance. “Governance” describes the management oversight in controlling risks. Governance includes the process and committees formed to manage risk. Governance reflects leadership tone at the same time. This means that governance reflects the core values of the organization towards risk, including the ability to enforce policy, the importance given to protecting customer data, and the tolerance for taking risks.

FYI

A GRC study by the Enterprise Management Association (EMA) published in 2008 identified the top three best practices frameworks. They are:

• ISO 27000 series

• COBIT

• COSO

“Risk management” describes the formal process for identifying and responding to risk. The concept beyond this part of GRC is a close alignment of business process and technology. This approach ensures risks are assessed and managed within the context of the business. Risk management also reflects leadership’s risk appetite. How far is leadership willing to go to ensure third-party vendor protection of the organization’s data? This view of risk can be reflected in leadership acceptance of risk, ranging from accepting vendor representation to insisting on on-site audits.

“Compliance” refers to processes and oversight necessary to ensure the organization adheres to policies. Compliance also includes regulatory compliance. An organization’s internal policies should address external regulatory concerns. Therefore, for organizations with well-defined policies, the focus is mainly on internal policies. If you can show evidence of adherence to internal policies, you can demonstrate regulatory compliance. The ability to demonstrate regulatory compliance is further enhanced when an organization can demonstrate the adoption of a best practices policy framework.

A framework helps create an enterprise view of risk. Many organizations have complex business and technology environments. The need to align these environments is critical. Organizations also find themselves facing increased pressure from regulators to demonstrate compliance. As a consequence, adoption of best practices provides leaders, regulators, shareholders, and the public the assurance each group requires.

Another framework approach is enterprise risk management (ERM). This framework aligns strategic goals, operations effectiveness, reporting, and compliance objectives. ERM is a methodology for managing a vast array of risks across the enterprise. ERM is not a specific set of technologies. As an example, the ERM function may look at credit or market risk and attempt to determine if the pricing strategy or compensation to the sales force is creating risk to the business. ERM is not an IT security policies framework. It is a good integration point for IT security issues to be considered in context to other risks.

What Is the Difference Between GRC and ERM?

The terms GRC and ERM are sometimes used interchangeably, but that’s incorrect. The difference is not in their goals. They both attempt to control risk. You can view ERM more as a broad methodology that leadership adopts to identify and reduce risks. There are similarities worth noting, as both approaches:

• Define risk in terms of the business threats.

• Apply flexible frameworks to satisfy multiple compliance regulations.

• Eliminate redundant controls, policies, and efforts.

• Proactively enforce policy.

• Seek line of sight into the entire population of risks.

GRC is more a series of tools to centralize policies, document requirements, and assess and report on risk. Because GRC is tools-centric, many vendors have created GRC offerings. It’s not surprising that with vendors aggressively selling solutions, GRC has more momentum than ERM. That’s not to suggest there aren’t tools to support the ERM process. Many of the GRC tools can be used to support the ERM methodology. But as a methodology, ERM adoption is driven by the organization’s leadership.

The lines between GRC and ERM do blur. In the real world, ERM teams deal with governance and compliance issues all the time. They use many of the same tools and techniques. More and more, GRC teams are reaching out to risk committees and teams to align efforts at a leadership level.

The important distinction is that ERM focuses on value delivery. This shifts the discussion from organizations’ budgetary requirements for risk mitigation, compared with how their expenditures enhance value. ERM takes a broad look at risk, while GRC is technology-focused. This broad view of risk considers technology as one aspect of risk among many. This can be either a benefit or a drawback depending on the leadership ability to understand IT risk. One of the benefits is that a successful implementation of ERM leads to risk management being fused into the business process and mindset.

Case Studies and Examples of IT Security Policy Framework Approaches

The case studies in the section reflect actual risks that were exploited in the real world. Each case study examines potential causes. By looking at these policies in the context of security policies, you can identify how they might be avoided. The case studies examined in this section include:

• Private sector—Relates to leveraging PCI DSS to prevent credit card data being stolen

• Public sector—Relates to a breach by an NSA contractor that leaked details on the U.S. intelligence Internet surveillance program

• Critical infrastructure—Relates to an energy company using COBIT to better control technology growth and business risks

A franchisee of a national hamburger chain in the southern United States was notified by Visa U.S.A, Inc. and the U.S. Secret Service of the theft of credit card information in August 2008. The franchisee has a chain of eight stores with annual revenue of $2 million.

The chain focused on the technology of its point-of-sale (POS) system. A leading vendor that allowed for centralized financial and operating reporting provided the POS system. It used a secure high-speed Internet connection for credit card processing. The company determined that neither the POS nor credit card authorization connection was the source of the breach. Although the POS was infected, the source of the breach was the network. Each of the franchisee’s stores provided an Internet hotspot to its customers. It was determined that this Wi-Fi hotspot was the source of the breach. Although considerable care was given to the POS and credit card authorization process, the Wi-Fi hotspot allowed access to these systems. It was determined the probable cause of the breach was malware installed on the POS system through the Wi-Fi hotspot. The malware collected the credit card information, which was later retrieved by the thief.

This was a PCI DSS framework violation. The PCI DSS framework consists of over 200 requirements that outline the proper handling of credit card information. It was clear that insufficient attention was given to the network to ensure it met PCI DSS requirements. For discussion purposes, the focus is on the network. The PCI DSS outlines other standards that may have been violated related to the hardening of the POS server itself. The following four PCI DSS network requirements appear to have been violated:

• Network segregation

• Penetration testing

• Monitoring

• Virus scanning

PCI requires network segments that handle credit cards be segmented. It was unclear whether there was a complete absence of segmentation or if weak segmentation had been breached. PCI DSS outlines the standards to ensure segmentation is effective. If the networks had been segmented, this breach would not have occurred.

PCI requires that all public-facing networks be penetration tested. This type of testing would have provided a second opportunity to prevent the breach. This test would have uncovered such weaknesses within a Wi-Fi hotspot that allowed the public to access back-end networks.

PCI also requires a certain level of monitoring. Given the size of the organization, monitoring might have been in the form of alerts or logs reviewed at the end of the day. Monitoring could include both network and host-based intrusion detection. Monitoring may have detected the network breach. Monitoring may also have detected the malware on the POS system. Both types of monitoring would have provided opportunities to prevent the breach.

PCI requires virus protection. It was unclear if this type of scanning was on the POS system. If it was not, that would have been a PCI DSS violation. Such scanning provides one more opportunity to detect the malware. Early detection would have prevented the breach.

The PCI DSS requirements are specific and adopt many of the best practices from other frameworks such as ISO. The approach is to prevent a breach from occurring. Early detection of a breach can prevent or minimize card losses. For example, early detection of the malware in this case study would have prevented card information from being stolen. Some malware takes time to collect the card information, which must then be retrieved. Quick reaction to a breach is an opportunity to remove the malware before any data can be retrieved.

Public Sector Case Study

In May 2013, Edward Snowden, a National Security Agency (NSA) contractor, met a journalist and leaked thousands of documents detailing how the U.S. conducts intelligence surveillance across the Internet. In June 2013, the U.S. Department of Justice charged Snowden with espionage. Not long afterward, Snowden left the United States and finally sought refuge in Russia. The Russian government denied any involvement in Snowden’s actions but did grant him asylum.

While this story reads like a spy novel, it raises a number of information security policy questions. For this discussion is not important whether Snowden was a traitor, a spy, or a whistleblower. The issue here is the security policies and controls that allowed a part-time NSA contractor to gain unauthorized access to highly sensitive material. This is particularly important because in April 2014, the Department of Defense announced adoption of the NIST standards. Would the Snowden breach have been prevented if the NIST standards had been adopted earlier?

Given the secret nature of the NSA, the full details of how this breach of sensitive data occurred may never come out. However, reports indicate that Snowden worked part time for an American consulting company that did work for the NSA in Hawaii. There he gained access to thousands of documents that detailed how the U.S. government works with telecommunication companies and other governments to capture and analyze traffic over the Internet. The details of the scope and nature of this global surveillance program were not publicly known and considered secret.

It’s clear from the reporting that Snowden had excessive access; that is to say, he was granted access beyond the requirements of his job. Additionally, reports indicated that he used other people’s usernames and passwords. He obtained these IDs through social engineering. Finally, consider the way in which he accessed and captured the information. Some reports indicate he used inexpensive and widely available software to electronically crawl through the agency’s networks. There are also indications that he removed the information on a USB memory stick.

FYI

Social engineering refers to the use of human interactions to gain access. Typically it means using personal relationships to trick an individual into granting access to something you should not have. For example, you might ask to borrow someone’s keycard to use the restroom but instead use the keycard to access the data center. Or perhaps you might ask for someone’s ID and password to fix his or her computer, and then later use those credentials to access customer information.

If he had used a Web crawler to automate the capturing of thousands of documents, Snowden would have been using software that is widely available over the Internet, and free of charge. Web crawler software simply starts browsing a Web page looking for links and then downloads related content. A Web page then links the Web crawler to another page and the process starts all over again. Thousands of Web pages are quickly scanned in a matter of minutes or hours, depending on the content. More sophisticated Web crawler software looks for specific documents to download. Snowden worked at the NSA for several months, accumulating thousands of documents and reportedly had access to 1.7 million documents in all.

There were clear NIST framework violations. For purposes of this discussion, the focus is on the network and social engineering. NIST publications outline other standards that were violated, such as effective security management and oversight.

The following four NIST framework network policies were clearly violated:

• Sharing of passwords

• Excessive access

• Penetration testing

• Monitoring

It’s never a good idea to share passwords. This would be a clear violation of security policy, especially by anyone handling classified data. Additionally, the level of access must be considered a policy violation. Any security framework generally prohibits granting access not related to the individual’s job function. It’s clear from the volume of material involved in the Snowden affair, and its classified nature, that the access he was granted was excessive for the role he performed.

The NIST framework outlines the guidance on penetration testing. Such testing would have clearly demonstrated the weaknesses of controls that allowed a Web crawler to scan and download thousands of documents. This type of testing and assessment would provide another opportunity to correct the network control deficiencies prior to a breach.

The NIST framework outlines the requirements for effective network monitoring. These requirements require logs to be reviewed in a timely manner. Log reviews are a detective control and essential in identifying potential hackers. Keep in mind Snowden scanned the internal network for months while downloading vast amounts of data. Hackers tend to probe a network for weaknesses prior to a breach. Assume that some of those links the Web crawler attempted to access resulted in an access violation. These violations would have been an indicator of a potential breach in progress. This type of monitoring would have provided another opportunity to correct the network control deficiencies and identify Snowden as an internal hacker.

Finally, consider the lack of controls that allowed Snowden to remove so many documents on a USB memory stick. This unusual activity could have been prevented, or, at a minimum, detected, given the volume of material extracted—especially given that many organizations have in place additional controls to monitor contractor activities.

Some of the specifics of the Snowden breach may never be known. Nonetheless, a security policy framework must be a comprehensive way of looking at information risks and ensuring there are layers of controls to prevent data breaches. This case is typical of a breach occurring over many months, indicating the breakdown of multiple controls. It represents both a lack of effective security policies and lost opportunities to detect a breach over several months.

Critical Infrastructure Case Study

Adnoc Distribution is an energy company with revenue of more than $3 billion. In 2008, Adnoc was expanding its energy business from petroleum into new areas, such as natural gas. The company’s IT environment was also growing, supporting expanded business markets and field projects. The amount of IT resources was not proportionally increased. This resulted in internal confusion and served to degrade IT services. Many of the IT processes were not standardized, which contributed to the problem. Generally, IT was considered an operating cost that did not require additional investment. Pressures on IT to deliver continued to increase as services continued to decline.

To reverse this trend, management selected COBIT as a means to add discipline, improve service, and increase customer satisfaction levels. COBIT also brought the IT governance necessary to better align with the business’s goals and provide effective oversight of the IT investments. The project was considered successful.

Some key areas of improvement noted after the COBIT implementation included:

• Value delivery

• Resourcing of IT

• Communication

With limited resources, delivering value can be a challenge. By better aligning with the business objectives and priorities, IT was able to focus resources on the project with greatest benefit to the business. COBIT was able to improve the value delivery by directing the IT resources more effectively into the areas vital to business goals. Confusing priorities were eliminated, implying a cost savings. Resources are wasted and costs rise when projects are started, stopped, restarted, and abandoned. COBIT ensures the appropriate controls were in place so management can exercise effective prioritization and delivery of technology solutions. COBIT was also flexible in that it aligned with other framework standards at Adnoc such as ISO.

As the business saw value in what IT was delivering, it made funding the technology easier. The resources devoted to IT depend on the perceived and actual value of solutions delivered. As COBIT better aligns an IT department with the business, the perceived value is improved. This is because the business sees IT as providing solutions for important problems.

A major benefit of COBIT is the alignment between the business and technology. What’s comes from this alignment is better communications. Tangible benefits accrue to an organization when business and IT can effectively communicate needs and risks. This communication allows for risks to be systematically identified and mitigated. It also allows tailoring of solutions to meet the business need. COBIT ensures processes are in place so issues can be quickly identified and resolved.

![]() CHAPTER SUMMARY

CHAPTER SUMMARY

This chapter examined various IT security policy frameworks. The frameworks share many of the same concepts and goals of controlling risk. However, their approach and scope of coverage differs. The chapter discussed how these differences are not always in conflict, but rather create an opportunity to adopt strengths of multiple frameworks such as COBIT and ISO. The chapter walked through methods to identify which best practice is appropriate for an organization. Implementation approach to framework will vary by type of framework and organization culture.

The chapter examined separation of duties from a roles and organizational view. The organization view was used to create three lines of defense to enhance the risk management program. Finally, the importance of the frameworks was highlighted in case studies. These case studies illustrated how implementing a policies framework to control risk prevents breaches and ensures compliance. The case studies also show how contractors and insiders can be as much as a threat as external hackers.

Audit committee

Best practices

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO)

Compliance risk

Control Objectives for Information and related Technology (COBIT)

Data administrator

Data security administrator

Data steward

Enterprise risk management (ERM)

Executive committee

Financial risk

Governance, risk management and compliance (GRC)

Head of information management

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

Layered security approach

National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

Operational risk

Operational risk committee

Risk Evaluation

Risk Governance

Risk Response

Security committee

Security event

Social engineering

Strategic risk

Value delivery

![]() CHAPTER 8 ASSESSMENT

CHAPTER 8 ASSESSMENT

1. The security committee is the key committee for the CISO.

A. True

B. False

2. Which of the following is not an IT security policy framework?

A. COBIT

B. ISO

C. ERM

D. OCTAVE

3. Which of the following are PCI DSS network requirements?

A. Network segregation

B. Penetration testing

C. Virus scanning

D. All of the above

E. A and B only

4. Which of the following are common IT framework characteristics?

A. Risk-based management

B. Aligned business risk appetite

C. Reduced operation disruption and losses

D. Established path from requirements to control

E. All of the above

F. A and C only

5. Which of the following applies to both GRC and ERM?

A. Defines an approach to reduce risk

B. Applies rigid framework to eliminate redundant controls, policies, and efforts

C. Passively enforces security policy

D. Seeks line of sight into root causes of risks

6. The underlying concept of SOD is that individuals execute high-risk transactions as they receive pre-approval.

A. True

B. False

7. A risk management and metrics team is generally the first team to respond to an incident.

A. True

B. False

8. Once you decide not to eliminate a risk but to accept it, you can ignore the risk.

A. True

B. False

9. Which of the following is not a key area of improvement noted after COBIT implementation?

A. Value delivery

B. Decentralization of the risk function

C. Better resourcing of IT

D. Better communication

10. A security team’s organizational structure defines the team’s ________.

11. Implementing a governance framework can allow an organization to systemically identify and prioritize risks.

A. True

B. False

12. The more layers of approval required for SOD, the more ________ it is to implement the process.

13. Asking to borrow someone’s keycard could be an example of ________.

14. All organizations should have a full-time team dedicated to collecting, reviewing, and reporting to demonstrate adherence to regulations.

A. True

B. False

![]() ENDNOTE

ENDNOTE

1. “Supervisory Guidance on Operational Risk Advanced Measurement Approaches for Regulatory Capital” (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, July 2, 2003). http://www.occ.treas.gov/ftp/release/2003-53c.pdf (accessed April 30, 2010).