CHAPTER 2

WHAT ARE THE COMMON OBSTACLES AND FEARS?

Of all the liars in the world, sometimes the worst are our own fears.

Rudyard Kipling

As human beings, we have a fundamental need to connect. In the workplace, we can benefit from creating deeper meaningful relationships in whatever role we have: managers, leaders and followers. It seems a simple, no-brainer route but the reality is that most of us are experiencing major threats to our ability to connect. If it is such an important factor, why do we stumble in creating and maintaining it in our personal life, workplace, politics and internationally? The reward of positive connection affects everything from engagement and productivity to health, well-being, longevity and yet most of us struggle with it.

There is a simple explanation, the one that explains why we don’t engage in many behaviours that can potentially improve our quality of life and well-being, like diet, exercise, rest. We have a natural tendency to take the easiest path, the one that would feel good in the short term. Yet, being connected feels good, so why don’t we prioritise it?

This chapter will give you the ability to:

- ■understand the risks of negative connection

- ■become aware of key external and internal barriers for connection. Some of them will be applicable to you, some won’t, and some might be food for thought and catalysts for future actions. Becoming aware of our barriers and obstacles naturally renders itself to improving connections.

First, we want to look at an example of the consequence of having poor connections in a well-known case.

WHAT HAPPENS TO ORGANISATIONS WITHOUT GOOD CONNECTIONS?

When Fred Goodwin, in the mid-2000s, initiated a merger between the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) and ABN AMRO, he neglected to take into consideration the need to connect and consult with his own senior management team. Under his leadership, the organisational culture became one of greed and fear. Top executives reported they were encouraged to forge signatures of key customers. The atmosphere in the bank was toxic, which meant that senior leaders were frightened to challenge the CEO. In response to any dissent, Fred Goodwin reacted aggressively and made them redundant. This resulted in the worst merger in corporate history, with lawsuits and a loss of billions. Fred Goodwin was stripped of his knighthood and will go down in history with the unflattering label of ‘Fred the Shred’ (Robinson, 2012).

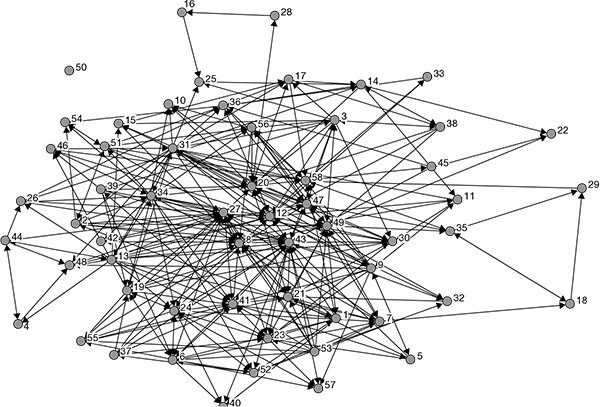

Linder, Cross and Parker (2006) studied how social networks drive change and innovation. They conducted a social network analysis on RBS in the mid-2000s which showed that several individuals were highly connected (for example, 47, 12 in the following figure) and therefore had a great deal of influence and information. However, there was a senior leader who was totally disconnected from others. Guess who?

EXERCISE

It’s your turn to create your own connection network. You can use it to see how your relationships are impacting you, and which connections you might need to improve to achieve your goals.

- 1.First, on a blank page, make a circle that represents you and write your goal. For example, getting a promotion, improving team productivity, executing a change plan or focusing on well-being.

- 2.Then, place all the people you interact with at work around this circle. Place people, key stakeholders, organisations that are important to you closer.

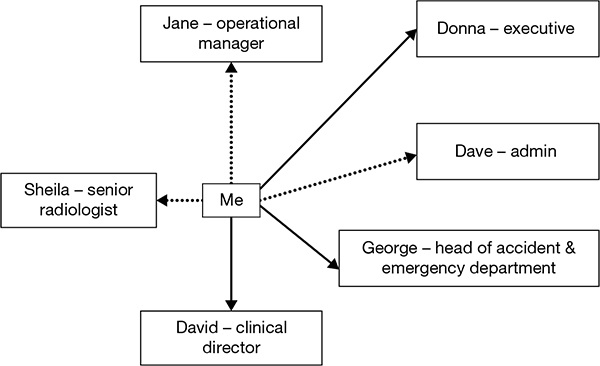

- 3.Later, draw a line between you and others. If it is a good/supportive relationship, draw a straight line and if it is a conflicted relationship, draw a dotted line (see a sample diagram below). Please be aware that what you consider ‘important’ or ‘less important’ stakeholders can change over time. This map can help you navigate the landscape and prioritise your actions.

An example of a connection network – my goal is to implement change in a radiology department in a hospital

In order to introduce change effectively within the radiology department, I need to continue to maintain my positive relationship with David (clinical director) and George (head of accident & emergency department), as well as Donna (executive on the hospital’s board). However, it is imperative that I focus on improving my connection first with Sheila (senior radiologist), then Dave (admin) and Jane (operational manager), who are currently not close to me and are highly important for the success of the implementation of the project.

Try today to do your own connection network

- ■Identify the relationships that are currently significant and your existing connection with them and vice versa.

Now that you can see it:

- ■How does it feel?

- ■Is there anything you would want to change?

Throughout the chapters, we will refer to this map and suggest ways on how you can use it. We recommend doing this exercise after reading the book.

Remember: lack of connection has far wider consequences than just financial.

WHY CONNECTION IMPACTS THE BOTTOM LINE

Engagement at work is the holy grail of every business. However, a recent Gallup report revealed that 13% of workers are actively disengaged and have miserable experiences at work. This is the lowest percentage since 2000. Engaged employees are innovative and always have an idea or two about what they can do better. Unengaged employees often have an idea or two on how to sabotage organisational performance (Harter, 2018).

Gallup’s measure of engagement uses 12 key questions. Their questions focus on having the tools/equipment to do the work, recognition of performance and personal development. Half of the other questions in their questionnaire directly relate to connection.

EXERCISE

See below some of Gallup’s questions. Can you try to answer some of these questions on how you feel at your current workplace? After answering the questions below, can you think about how this impacts on the organisation’s bottom line?

- ■Do I have a best friend at work?

- ■Does my supervisor, or someone at work, seem to care about me as a person?

- ■Does the mission of my company make me feel my job is important?

- ■In the last six months, has someone talked with me about my progress?

The above questions relate directly to the connectivity of employees to others at the workplace as well as to the wider organisational mission and values. Our goal throughout the book is to explain what we can do in order to dare to care, create an environment where people support each other, and develop closer relationships at work.

The lack of connection is especially visible when dealing with the role of line managers. They are squeezed in the middle (Oshry, 1999) and have a critical role in connecting between the mission, senior management and frontline staff. Branding and culture expert Denise Lee Yohn (2017) explains that middle managers, ‘wield the most influence on employees’ daily experiences’. When properly equipped, engaged and empowered, middle managers enhance overall performance: productivity, customer and employee retention, and team alignment to the company mission and strategic goals. When they are disconnected, the entire organisation performs poorly, resulting in loss of productivity, lower morale, increased attrition or all of the above. Zenger and Folkman (2014), in an influential Harvard Business Review article, reached a similar conclusion. They researched 320,000 employees across different sectors and found out that the most disengaged population in an organisation was ‘the people who were stuck in the middle of everything’. However, organisations across the board do not invest in this critical layer of the organisation. Munch (2017), chief clinical director, Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston, USA, claims that even in a complex healthcare environment, senior management is reluctant to invest in middle management development, which results in poor execution of strategic plans and a waste of resources. Management in both Google and Netflix understood this.

Google, known for its informal working environment, allows engineers and developers to take 20% of their time to spend on innovative projects. The underlying message for the engineers is that Google trusts middle management connection to the wider organisational strategy and therefore will know how to use their time effectively. Indeed, it is a known fact that half of their new product launches can be traced back to ‘innovation time’. It can also explain why Google is at the top of Fortune magazine’s list of best companies to work for multiple times.

Netflix tasked line managers to play an active role in shaping the organisational culture. McCord (2014), HR director of Netflix, explains in a Harvard Business Review article that 97% of their employees are connected to the overall strategic vision of the business and will do the right thing. As a result, there is no formal system of taking time off at Netflix. Instead, employees can take time off when they feel it’s appropriate. Bosses and employees are asked to work it out together, with an overall guiding principle that is to act in ‘Netflix’s best interests’. This trust has yielded a significant improvement in both employees’ productivity and willingness to go the extra mile. There is a new generation (i.e. millennials) coming to power that is adamant about bringing new values to the table. They want to feel connected to organisations with social values/mission as well as demand opportunities for growth and development (Honoré & Paine Schofield, 2012). Ignoring their core values will have implications on the quality of the organisational talent pipeline and consumer loyalty.

EXERCISE

Questions for reflection

From a scale of 1 (low) – 10 (high), how do you perceive the level of engagement of staff in your organisation?

From a scale of 1 (low) – 10 (high), do line managers in your organisation view themselves as the ‘guardians of culture’?

![]()

Are you paying enough attention to how you recruit and retain the new generation/millennials coming into work? Mark your answer on a scale of 1 (low) – 10 (high).

![]()

From a scale of 1 (low) – 10 (high), how supported do you feel at work?

![]()

If you scored:

- 40: excellent (your organisation is well connected)

- 35–40: good (there are some good practices but you can do better)

- below 35: need improvement (see recommendations on how to improve organisational culture and connections in Part III).

LONELINESS CONTRIBUTES TO POOR WELL-BEING AND PERFORMANCE

Dan Schawbel (2018), The New York Times bestselling author, argues that we live in the age of isolation. EU figures suggest that, in the UK as a whole, 13% of the population lives alone. Denmark has the highest proportion of single-dwellers, at 24%. In Germany, Finland and Sweden, that number is just below 20%. Recent research by the British Red Cross showed that there are nine million lonely people in the UK. They are struggling to make social connections and experience feelings of isolation. They are worried that no one will notice if something bad happens to them (Barr, 2018). Dr Andrew McCulloch, chief executive of the Mental Health Foundation (cited in Barford, 2013), argues that, ‘It’s not because they are bad or uncaring families, but it’s to do with geographical distance, marriage breakdown, multiple caring responsibilities and longer working hours. We have data that suggests people’s social networks have got smaller and families are not providing the same level of social context they may have done 50 years ago.’ This has led Theresa May (former UK Prime Minister) to nominate for the first time in history a cabinet minister for loneliness to address this phenomenon.

The wider societal problem around loneliness has been permeating into today’s workplace. A recent study by CNN News (Vasel, 2018) revealed the significant impact of loneliness on the productivity of organisations. Lonely employees have a lower job performance, are less committed to the company and seem less approachable to their co-workers. Within the study, Professor Hakan Ozcelik (2018), from the College of Business Administration at Sacramento State summarises this phenomenon. First, there are fewer human interactions at work, which lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness. Second, if you are not close to anyone, even working in the middle of an open-plan office can feel lonely. Within the same study, Professor Barsade from Wharton School (University of Pennsylvania) adds that, if we do not pay enough attention to feelings of loneliness, other people will mimic these behaviours. Loneliness can spread like a virus across the organisation. To reverse this downward trend, it is important to exchange real emotions, which are critical to friendship.

We will elaborate on this in Chapter 6 where we discuss the RESOLVE model as a tool to create meaningful connections.

We have found that the problem of loneliness is much more complex for high-performing senior leaders (mostly men). They find it hard to admit their weaknesses, feelings of loneliness and to seek help. Instead of discussing their emotions, they become more isolated in the workplace. There is a shift in the City of London with more understanding of the importance of emotional resilience and the popularity of mindfulness/relaxation courses (Norton, 2015). This is a positive change but still seems like a plaster on what is a much bigger problem.

EXERCISE

Questions for reflection

- ■Do you have systems and procedures to detect burnout and loneliness?

- ■Do your middle and senior managers discuss well-being/burnout/health as part of the usual business?

- ■Do you take care of yourself?

- ■Do you role model self-care to others?

If you want further information in this area, please read the self-care for leaders section in Chapter 5.

EXERCISE

Try to experiment each day this week with connecting with someone new to you within your existing social network at work. Try to find out something you did not know about them and their work.

Post-experiment reflection questions:

- ■What was the experience like?

- ■What was challenging?

- ■What was beneficial?

- ■What did you learn about yourself and others?

FOCUS ON THE TANGIBLES PREVENTS POSITIVE CONNECTIONS

Reynolds and Lewis (2017) argued that the quality of interactions is important to both the formulation and execution of strategy. In the business world, they claimed, there is not enough consideration of some of the more ‘intangible’ aspects of quality of interactions across the organisation. Instead, we tend to focus on the organisational structure/charts, new initiatives, teams and lose sight of the importance of some of the processes ‘beneath the surface’. They coined this pattern as the ‘Tyranny of the Tangible’. Emotions such as anger, fear, envy, as well as happiness and sense of achievement are shoved into the corners. The same fate awaits beliefs and doubts about yourself. They all get locked in the ‘intangible/irrational box’ and are put aside as irrelevant. However, the reality is that emotions and core beliefs govern our behaviour as much as the tangibles, such as cash flow and productivity measures.

When facing significant strategic dilemmas, senior managers prefer to reorganise the organisation, choosing to focus on what is under their control instead of dealing with the ambiguity of emotions. This is exactly like the joke about the person looking under the light for a penny he lost somewhere else. He is reluctant to search in the dark, even though that’s where the penny dropped.

The search for control and measurement has been one of the key reasons for the ‘target culture’ in the English National Health Service. Patients’ needs and quality of service were ignored at the expense of delivering short-term targets (West, 2018). A study by The King’s Fund revealed that this culture created a dominant ‘pacesetter’ leadership style among senior leaders, which is focused on achieving targets without consideration to group dynamics/interaction and trust between team members. Pacesetter leaders set high-performance standards, but neglect the relationships within the team. They roll up their sleeves and lead from the front rather than delegating to others (Fillingham & Weir, 2014).

EXERCISE

Questions for reflection

- ■Do you feel safe to express your emotions at work?

- ■How do you react when others express feelings at work, such as anger, sadness or joy?

- ■Does the organisational culture pay attention to ‘intangible’ aspects of the organisation, such as morale, emotional safety, motivation, emotional connection with mission and values? Do you have specific examples?

DYSFUNCTIONAL CULTURE

Culture is the water we swim in, the environment that surrounds us and dictates what is right, what is wrong, and how we live life. Schein (2017) describes culture as comprised of different levels. On the visible level, you have artefacts such as buildings, furnishings, dress codes and mission statements. Though, more importantly, ‘under the surface’ we have norms and behaviours that act as the glue that connects our families, organisations and communities. These are patterns that evolve through our everyday interactions, beliefs and meanings. They are learned, shared and reinforced through conversations, language, bodies, symbols, politics, rituals, stories, customs and technologies among other things. Is it OK to be late? Who gets to talk? Is conflict open or subtle/nuanced? Who makes decisions? Is this language/term OK to use or not? (Wiggins & Hunter, 2016). Over time, these can be taken for granted and become difficult to contest. When challenged, the people who lead the intervention are perceived as ‘difficult’, ‘weird’, ‘awkward’ and sometimes ‘irrational’ because they are threatening the status quo and the inherent fabric/need for connection.

Management thinkers such as Amy Edmondson (2012) argue that in order to effectively challenge established cultural norms, it is important to create a climate of psychological safety in which people can express themselves without fear of sanction.

Correlation is not causation and yet the lived experience of being connected and trusting supervisors and leaders showed a consistent impact on safety, patient satisfaction, medical outcomes and overall productivity.

Irving Janis (1982) coined the term ‘groupthink’. It is an example of how people ignore crucial information because of the pressure to join a collective defence mechanism of denial and avoid conflict over different points of view. Janis showed how experienced leaders can lead a group of people to overlook crucial information and he mentioned the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Cuban Missile Crisis and the attack on Pearl Harbor as examples to groupthink.

When the Challenger space accident happened over 30 years ago, we were reminded of the power of groupthink. Although the engineers at NASA were aware that the shuttle would explode, they were not able to convey the message to senior management. After putting a man on the Moon, senior management was caught in arrogance and groupthink, which prevented critical information from being taken on board, resulting in a grave accident. Schwartz and Wald (2003) argue that organisations have not learned and groupthink is still alive.

Kodak, despite having the technological knowledge of the digital camera, was too slow to react on this information and go to market. The company lost out to the competition and it took many years to turn the business around. Commentators relate this lack of adaptability to a culture that required people to conform to the views of senior management (Anthony, 2016).

Syed (2016), in his influential book Black Box Thinking, provides the example of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust to highlight the difficulty of healthcare as a sector to learn from mistakes and improve performance for the benefit of patients and staff. The inquiry into the failure of Mid Staffordshire revealed a culture/leadership of non-disclosure and defensiveness of failure at all costs, resulting in catastrophic consequences to patients’ safety, unlike the airline industry, which turned around the rate of accidents. In 2014, out of 36 million commercial flights only 210 people died (Syed, 2016).

In the healthcare sector, there are many examples of the lack of systematic and independent approaches to dealing with mistakes/accidents. The traditional power differentials between the professional groups (e.g. doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals) limit the ability to speak truth to power and challenge authority (Atul Gawande in Syed, 2016).

The defensive culture in the healthcare sector manifests itself in lack of learning opportunities and systematic difficulties in trying out new ideas and learning from failure. Staff members are worried about being blamed for improving and challenging existing practices.

EXERCISE

Try this today:

- ■Are there signs/organisational patterns of disconnection/arrogance within your organisation, especially within the senior management team?

- ■Are poor behaviours by senior leaders ‘tolerated’ by staff? Do staff feel safe and able to ‘speak up’?

- ■Choose an area in your organisational culture that you are concerned about, and have an informal conversation about this topic with a colleague whom you trust. What did you learn?

INTERNAL BARRIERS TO EFFECTIVE CONNECTIONS

TRAUMA AND ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCE

When we open the door to the office, we bring with our talents, knowledge and experience, also our hopes, fears, past and present failure and success, our history and our childhood experiences. For most of us, childhood is a mixed bag of good and bad experiences. Some experiences cast a long shadow on our ability to perform at work, feel safe and connect. People in the workplace don’t wear their childhood wounds on their sleeve and yet those experiences highly affect everything they do from 9–5 (or any other window of time that we spend at work).

Adverse childhood experience (ACE) is one of the most important studies related to the effect of childhood trauma and neglect. The study led by Dr Vincent Felitti and Dr Robert Anda was conducted from1995 to 1997. 17,000 Kaiser Permanente (health insurance company) patients were surveyed before their physical exam with a primary care medical provider. The survey contained 10 questions about patients’ childhood experiences, including having experiences of physical, sexual and verbal abuse, physical and emotional neglect, having a family member diagnosed with mental illness, addicted to alcohol or other substance, or incarcerated. It asked about losing a parent to separation, divorce or death. The survey also inquired about the history of sexual, physical, emotional abuse and neglect. Each positive answer got one point, so patients’ ACE score was from 1 to 10.

The findings showed that patients who experienced four or more adverse childhood events had significant increased risk for smoking, increased risk for depression and suicide/attempts, poor self-rated health, greater likelihood of sexually transmitted disease, and increased challenges in physical inactivity and obesity. The study also found a correlation between a high ACE score and health conditions like increased risk for broken bones, heart disease, lung disease, liver disease, and several types of cancer.

In an article published in The Permanente Journal (2004), a group of researchers examined the relationship between a high ACE score and three indicators of impaired worker performance (serious job problems, financial problems and absenteeism). They surveyed 9,633 employees. The results indicated a strong correlation between ACE score and worker performance. They stated in their conclusion: ‘The long-term effects of adverse childhood experiences on the workforce impose major human and economic costs that are preventable. These costs merit attention from the business community in conjunction with specialists in occupational medicine and public health.’ They also suggest that dealing with workers’ adverse childhood experiences would address the root origin of these problems in the workforce.

In the workplace, our small and big traumas are triggered daily. They are present in the way we interact with our peers, managers and the people we manage. We are wounded beings going to work.

It is important to remember that the fact that you are reading this book right now indicates the presence of resilience, which is the factor that helps us deal with adverse experiences in the past, present and future.

PROBLEMS IN SENSORY PERCEPTION AND COGNITION

Research by neuroscientists suggests that our perception of other people is instinctive. We confirm our mental models by using our voice, body language and face. Most of the time our perception is incorrect. It drives people to emphasise data that confirm their beliefs and to discard information that conflicts with their worldview. Executives emphasise evidence that their plans work and defend against any contrary data. If you’re an optimist, you’ll verify your positive viewpoint at every opportunity; if you’re a pessimist, you’ll find many reasons to see most situations negatively. Steve Peters describes this instinctive phenomenon as ‘the inner chimp’: the animal inside us decides on action before we formulate a more emotionally intelligent reaction (Peters, 2012). Mehrabian showed that when there is inconsis-tency between the words used and tone of voice and facial expression, we privilege and trust the message conveyed by the tone of voice and facial expression instead of the actual contents of the message (Mehrabian, 1981).

Neuroscientists explain that these errors in perception are due to our social needs, which are treated in the brain in a similar way to the need for food and water (Rock, 2008). Our brain networks and behaviours are organised by either minimising threat or maximising reward (Gordon, 2000). When a person encounters a stimulus, their brain will either tag the stimulus as ‘good’ and engage or their brain will tag the stimulus as ‘bad’ and avoid/disengage. The approach–avoid response is a survival mechanism designed to help people stay alive by quickly understanding what is good and bad in the environment. The amygdala, a small almond-shaped object that is part of the limbic system, plays a central role in this process. The amygdala will be activated proportionally to the strength of the emotional response (Phelps, 2006). When a boss appears threatening, or perhaps does not smile, suddenly a whole meeting can feel dangerous and people will not want to speak up or take risks.

In a meeting, the principle of approach–avoid will be triggered by what our brain work perceives as friends or foe. Somebody feeling threatened by a boss who is undermining their credibility is less likely to solve complex problems and more likely to make mistakes. The reduced cognitive ability is related to the sense of threat and loss of overall executive functions in the prefrontal cortex and less oxygen and glucose available for brain functions which impacts memory and problem solving (Arnsten, 1998). Just speaking about somebody higher in status is likely to activate an approach–avoid response.

Conversely, Fredrickson (2001) argues that when people experience positive emotions, they perceive more options when trying to solve problems that require insight and collaborate better. Relatedness involves deciding whether others are ‘in’ or ‘out’ of a social group. People like to form ‘tribes’ where they experience a sense of belonging. Information from people perceived as ‘like us’ is processed using similar circuits for thinking one’s own thoughts. When someone is perceived as a foe, different circuits are used (Mitchell et al., 2006).

This explains why our judgement of other people is made on guess work and assumptions rather than hard evidence. Research into job interviews reveals that we make decisions/judgements about people as soon as they walk through the door. Despite all of this evidence, we are often very confident of our ability to judge other people – whether on their competence, honesty or whether we like them or not (Cook, 1998).

When we treat someone as a competitor, the capacity to empathise drops significantly (Singer et al., 2006). A handshake, swapping names and discussing something in common, be it just the weather, may increase a feeling of closeness by causing the release of oxytocin (Zak et al., 2005). Relatedness is close to trust. The more people trust each other, the stronger the collaboration.

EXERCISE

Try this today:

- ■Think of someone within your immediate network that you ‘dislike’. Can you try and use some of the above suggestions to increase connection and trust? (For example, share something personal about yourself, offer support, ask them questions about their interests and/or recent success.)

- ■What did you learn?

WHAT TO DO NEXT

You may find it useful to dip into Chapters 3 and 4 that help you identify personal connector types and how to communicate across people with other connector styles. Chapter 6 has the RESOLVE model that can help you handle a difficult relationship. Chapter 7 has seven ways to create positive connection. Both Chapters 8 and 9 offer tips on how to improve connections across generational gaps and cultures. Chapter 10 has useful tools on how to stay connected in a digital age.

SUMMARY AND ACTIONS

- ■Positive connection is fundamental to human beings and closely correlated with individual health and well-being. We continuously seek connection and, at the same time, have difficulties relating to and getting along with others.

- ■There are internal and external barriers for positive connection.

- ■Companies that invest in creating positive cultures for staff have significantly better staff morale/well-being and bottom-line performance. Conversely, destructive organisational culture can result in poor communication, low productivity, lack of innovation and, in some cases, can contribute to tragic outcomes.

- ■It’s important to become aware of the tricks that your mind can play and personal biases that may impact negatively on your judgement and decision making.

Action plan for improving connection:

- ■Identify whether the barrier for connection is internal or external. If it’s internal; does it remind you of past negative experiences?

- ■You can also examine your connector type (Chapter 3) and improve your self-esteem and ability to connect with others and/or employ the RESOLVE model in Chapter 6 that helps you handle a difficult relationship.

- ■If it is an external barrier for connection, ask yourself, is there something I can do about it? Look at Chapter 8 connecting across cultures and 9 connecting across ages. In addition, you will find useful tips in Chapter 7 on the seven ways of connecting and Chapter 10 (connecting in a digital age).