p.60

Current practice and future directions

Darin Gates, Bradley R. Agle, and Richard N. Williams

Business ethics is a burgeoning field of study and practice with vibrant academic and practitioner communities. Due to a combination of pioneering leaders in business and academe, many resources are currently being expended to understand and manage ethics in business.1 Unfortunately, however, we would argue that the actions of the unscrupulous in business have probably had a greater effect on the growth of the field than have its leaders. Every time there is a major scandal or controversy in business, or set of scandals or controversies (some of the “high” points include the mid 80s, early 90s, and the crisis of 2008), calls are made for reform, including further regulations (e.g., 1991 US Sentencing Guidelines, and Sarbanes-Oxley (2002)) and greater emphasis on ethics in companies and in business schools. Consequently, academic ethics organizations, and corporate ethics and compliance associations, are healthy and strong, allowing academic and business specialists to find conferences on the subject virtually every month of the year.

Included in the call for reform and greater resources is almost always a desire for greater education and training in business ethics. The American Association of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) has responded with accreditation standards requiring that ethics be part of a business school’s curriculum, and major businesses have responded by almost uniformly providing some level of ethics training. With this increase in resources has come a bevy of questions related to the what, why, where, when, and how of ethics education. In this chapter we will briefly discuss ethics training in organizations and then focus on how these questions are being addressed in the academic community, with much of the description drawing from experience within North America. In particular we will first address the history, current status, and future trends in business ethics education (including various aspects of behavioral ethics), and then delineate, in the subsequent section, an account of a business ethics pedagogy that should diminish the appeals to self-interest and to relativism, as well as alert students to the types of moral blindness and self-deception that often accompany unethical actions.

Business ethics: education vs. training

While discussions of trade, wealth, or the vocation of commerce have been around for millennia, the first attempt at formal, academic discussion of business ethics in the United States began with the introduction of business schools in the late 1800s and early 1900s (Khurana 2007). As Rakesh Khurana explains in his book From Higher Aims to Hired Hands, the original intent was to model these schools after professional medical and law schools, with a highly integrated professional code of ethics. However, such a vision never materialized, and business consequently evolved for decades without an explicit emphasis on ethics. The modern business ethics movement started primarily among philosophers in the 1970s and 1980s (for an alternative history see Abend 2014) and began to become much more common in business schools in the 1990s and 2000s. As the field has grown and attracted academics with varied backgrounds (e.g., law, psychology, marketing, business, sociology), a lively discussion has ensued regarding the purposes of and pedagogical approaches to the teaching of business ethics. In ensuing sections we will address the history, current status, and future directions of business ethics education (mainly in the US) through the lens of the major questions that tend to be asked about business ethics education, namely—why, what, how, where, and when.

p.61

As we discuss business ethics education, it is important to distinguish between education performed in an academic setting and ethics education (training) done within corporations. The number of organizational ethics training programs is on the rise: in 1986, the Center for Business Ethics found that only 44 percent of companies reviewed conducted training, whereas, most recently Weaver et al. (1999) found that 66–80 percent of firms offer such programs. However, very little work has been done to analyze the details or characteristics of these programs. The one outstanding attempt to investigate and assess details of ethics training was conducted by James Weber (2015). Weber examined employee ethics training programs among 70 US-based global organizations by asking members of the Ethics and Compliance Officer Association to describe various elements of their organizations’ ethics training programs. We summarize selected results from Weber’s (2015) research in the next three paragraphs of this section.

The adoption of employee ethics training has consistently increased and has now joined the ranks of organizational ethics policies as commonplace among large US business organizations. The ethics officers also report that their training seeks to empower employees to become more aware of ethical issues faced at work, to be better equipped with ethical decision-making skills, and thus better able to resolve ethical challenges faced at work. In conducting the training, a variety of approaches are used. By far the most common approach is using a computer-aided (online) training program. Engaging employees in a group setting to discuss general ethics topics or cases is also a common approach. Nearly half of the ethics training programs included lectures as the teaching approach.

Emphasizing group interaction is often an effective approach (as noted by other scholars, Elkjaer 2003; Morris and Wood 2011). However, the emergence of online or technology-enhanced training and the use of the lecture method without other, educationally proven, techniques is suspect. It is understandable that business organizations prefer web-related training approaches, since these can offer significant time and cost savings, but there is little evidence that such an approach is more or even as effective as face-to-face training in promoting ethics. Too often, businesses rely on short, infrequent, or at-orientation training sessions, which are also likely ineffective. One particularly troubling discovery is that only 30 percent of firms indicated that the impact or outcome of the ethics training programs is measured. When assessment is conducted at all, it generally relies on weak tools or metrics, rendering the effectiveness of such training questionable.

There also exists a strong consensus among ethics officers as to the challenges or obstacles faced in developing and offering an employee ethics training program. The most frequently mentioned obstacles were, in order: 1) finding the time to conduct the training, 2) acquiring sufficient resources (money), and 3) keeping the training program relevant and engaging for participants. Other ethics officers noted the challenge of administering their ethics training program given “multicultural diversity, variations of relevancy around the globe, and language differences.” Finally, the challenge of “integrating the training into the work performed by the employees” and “coordinating ethics training with other training programs offered by the organization” were mentioned as well (Weber 2015: 34).

p.62

The why, what, how, where, and when of business ethics education

Why?

What are the purposes for teaching business ethics? Agle and Crossley (2011) provide a review of the objectives of ethics education. Their literature review finds 35 different objectives that have been set forth as the aims of a business ethics education. Their study suggests that the four most commonly mentioned objectives refer to 1) ethical decision-making skills (Warren 1995), 2) moral awareness (Sims and Felton 2006), 3) understanding of one’s own values and principles (Hartman 2006), and 4) comprehending the place of business in society (LeClair et al. 1999). In addition to these four aims, other commonly noted objectives include the following: 1) the development of rhetorical skills in order to become effective advocates for ethical positions (Duska 2014), 2) the development of moral courage (Mason 2008), 3) advancing to moral leadership (Verschoor 2006), and 4) the attainment of moral character (Armstrong et al. 2003).

Many argue that greater moral awareness (e.g., Sims and Felton 2006), along with stronger cognitive abilities, both theoretical and practical, related to ethics (e.g., Heath et al. 2005; Berenbeim 2013), should be the objective of our ethics-education efforts. Such objectives are bolstered by empirical findings demonstrating that because of consumer capitalism, hyper-individualism, failures in education, and extreme moral relativism, young adults in America today are generally unable to identify and grapple effectively with moral issues (Smith 2011). Generally, the hope is that greater cognitive abilities will lead to more ethical behavior. While we continue to believe in this link, the empirical evidence of such a relationship has yet to be demonstrated. In fact, new research suggests that emotions and environment play a stronger role in ethical conduct than does cognition (Greene et al. 2001; Greene and Haidt 2002; Sonenshein 2007).

Moving into the future we believe that while a continuing emphasis will be placed on moral awareness and sound ethical decision-making, greater priority will be placed on understanding the drivers of unethical behavior and working to counter such behavior.2 The two major trends moving us in this direction are behavioral ethics (e.g., De Cremer and Tenbrunsel 2012; Bazerman and Tenbrunsel 2011; Bandura 1999), and the positive reception that has followed a specific book, Giving Voice to Values (Gentile 2010). Behavioral ethics is the study of how individuals not only think but act when confronted with ethical issues. Arising primarily from the work of psychologists and economists, behavioral ethics accents phenomena such as ethical fading3 (Bazerman and Tenbrunsel 2011), moral disengagement4 (Bandura 1999), and neutralization techniques (Sykes and Matza 1957),5 as well as behavioral tendencies such as cheating (Ariely 2012), pro-social behaviors (Grant and Gino 2010) and the effects of ego-depletion on such tendencies (Gino et al. 2011). Future educational efforts will provide greater emphasis on individuals understanding these behavioral tendencies in order to recognize and avoid them (Haidt 2014). We would argue, however, that as important as these insights are, behavioral ethics can never replace, but only supplement, normative business ethics (see Nagel 2013).

Authored by Mary Gentile, Giving Voice to Values is not just a book but a catalyst for a movement. A former ethics educator at the Harvard Business School, Gentile underwent a crisis of conscience while teaching ethics, wondering if her efforts were doing any good in making the business world a more ethical place. Her epiphany came years later while doing consulting work. She came to the realization that students needed a better understanding of how to do what is right (or, at least, to act in accordance with their values) under difficult circumstances. Her book, and subsequent teaching materials and cases, provide tools for helping students and businesspeople practice how they will “voice their values.” Consequently, efforts are underway in academe and in business organizations to help individuals understand how to act in situations where demands made upon them are not in line with their values.

p.63

In order for ethics education to succeed in producing more ethical business people, it must be true that ethics can be taught. And yet, for many, the question of “Can ethics be taught?” seems to remain unanswered (Piper et al. 1993). Here, we need to distinguish between two questions, 1) can an ethics course teach someone to be ethical who has not already developed into a morally decent person? and 2) can such an ethics course teach a morally decent person to be more ethical? The former is highly dubious. The latter is almost certainly the case.

Numerous studies have concluded that there is a positive relationship between ethics courses and various aspects of ethical conduct. Weber (1990) was one of the first to review the business ethics education literature, concluding that, in general, such courses lead to some improvement in students’ ethical awareness and moral reasoning. The positive impact of ethics teaching on ethical awareness and moral reasoning has been confirmed by several other studies (Rest 1986; Glenn 1992; Earley and Kelly 2004; Williams and Dewett 2005; Carroll 2005; Lau 2010). Ethics teaching has also been found to positively impact ethical sensitivity (Gautschi and Jones 1998) and an appreciation of the complexity of ethical issues (Carlson and Burke 1998). Other studies that suggest that ethics can successfully be taught include Langlois and Lapointe (2010), Mayhew and Murphy (2009), Wurthmann (2013), and May et al. (2014). However, despite the studies that suggest ethics can be taught, other research finds minimal to no effect from ethics instruction (Simha et al. 2012), including a meta-analysis of such studies performed by Waples et al. (2009).

The contradictory evidence does not necessarily imply that ethics cannot be taught, but rather that in such cases, ethics was not taught effectively. Analogously, just because some diet and exercise programs don’t produce weight loss, one should not conclude that diet and exercise programs are not effective in helping with weight loss. So, the question is “How do we teach business ethics effectively?” In order to answer such a question, there is a pressing need for longitudinal research that explores the long-term effects of different pedagogical strategies and emphases on the multiple ethical outcomes of individuals (e.g., ethical awareness, sensitivity, decision-making, courage, leadership, etc.; see Agle et al. 2014).

What?

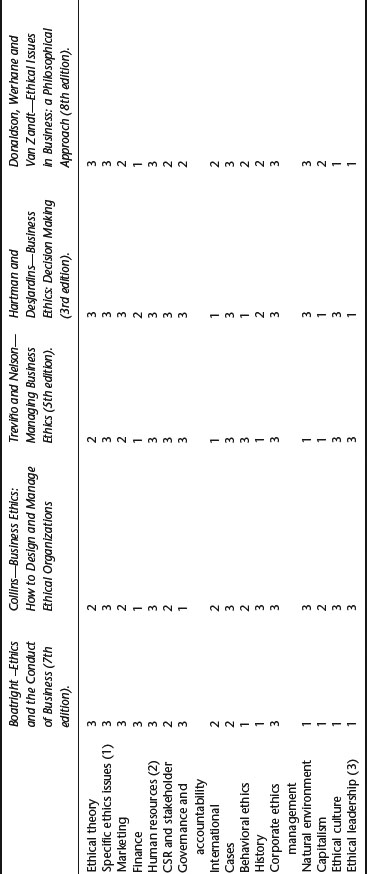

What is the content of business ethics education? Since current textbooks provide a perspective on what topics are currently being covered, we examined a sample of five leading ethics textbooks by authors with philosophy and management backgrounds. Table 4.1 provides a summary of the topical coverage of these textbooks.

Table 4.1 demonstrates that there is a continuing emphasis on ethical theory; real-world ethics cases; management issues involving human resources such as hiring, discrimination, employment rights, and occupational safety, and development of the corporate ethics infrastructure; marketing issues such as product safety, pricing, and advertising to vulnerable populations; corporate accountability and social responsibility; and specific topics such as whistleblowing, conflict of interest, privacy, and intellectual property rights. These topics tend to be the purview of the academic disciplines that have been most active in their examination of business ethics, namely philosophy, management, marketing, and law. Other topics with less uniform coverage include ethical leadership; behavioral ethics; analysis of capitalism; corporate culture; issues related to the natural environment; international, religious, and cultural influences on business; history; and ethics in finance. Because of the explosion in research in behavioral ethics we expect the coverage of some of these topics to increase in coming years; however, barriers to this shift are evident. For example, given several books such as All the Devils are Here by Bethany McLean and Joe Nocera (2010) that suggest that a major cause of the financial crisis of 2008 was caused by unethical behavior in the finance industry, one would expect the emphasis on ethics in finance to have increased significantly after the most recent US recession and global financial market crisis. However, we are not aware of any important movement among finance professors to examine ethics. Other topics are more difficult to cover because the landscape is so large (e.g., cultural and religious influences as in VanBuren and Agle 1998; Weaver and Agle 2002; Culham 2013), or the pedagogical approaches for effectively teaching them are just now forming. For example, while complicated, the rise of behavioral ethics suggests that experiential learning will be a growing aspect of ethics education. Several examples of such efforts currently underway will be covered in our “how” section.

p.64

Table 4.1 Topical coverage in a selection of ethics textbooks.

Notes:

1—Indicates minimal topic coverage; 2—indicates moderate topic coverage; 3—indicates extensive topic coverage.

(1) Specific ethics issues—Whistle blowing, conflicts of interest, privacy, affirmative action, safety, intellectual property.

(2) Human resources—Hiring, discrimination, employment rights, occupational health.

(3) Ethical leadership—Specific attributes and qualities of ethical business leaders.

p.65

Where?

In recent years a lot of discussion has centered on the question of “where in the curriculum” should business ethics be handled. In general the debate has involved a question of stand-alone versus integration. While the idea of integration continues to be popular, and an idea we wholly endorse when combined with a stand-alone course, empirical research indicates that implementation continues to be problematic, particularly in areas such as accounting and finance (Rasche et al. 2013). In our experience, in order for integration to have a chance of succeeding, a school must have a contingent of ethics faculty, dedicated and trained, who can teach and assist their colleagues in integrating ethics material into their classes. However, if a pure integration model is attempted, and no required ethics classes exist, then it is also likely that the institution has no dedicated and trained ethics faculty members available. For this and other reasons, most commentators (e.g., Swanson and Fisher 2008) believe that a combination of stand-alone classes and integration is necessary to really meet the various objectives of business ethics education. In a very persuasive essay at the beginning of their edited volume on business ethics education, Diane Swanson and Dann Fisher argue that integration without stand-alone ethics courses will fail because of 1) the poor signal it provides to students (namely, that ethics isn’t as important as other required topics), and 2) a lack of strong conceptual building blocks developed through extensive education by ethics educators.

In the context of this issue, Agle and Garff (2015) provide a much fuller discussion of how the various objectives of ethics can be met through the different elements of a student’s academic experience. For example, students will likely a) learn ethical theory best through a stand-alone ethics course; but they will b) hone moral awareness through exposure to ethics in their various disciplinary classes (one’s awareness is heightened when one is required to look for ethics in places where it is not advertised, as it is in an ethics course); they will then c) acquire corporate culture and grasp the moral infrastructure of organizational life through business school and university modeling (i.e., they see, experience, and are trained in the different elements of the university’s code of ethics, learn about the role of the ethics ombudsman, see the ethics hotline, etc.).

Universities and business schools have the ability to demonstrate how to build a strong ethical culture, both formal and informal (Treviño and Nelson 2010). If students receive training in such things as academic plagiarism, appropriate and inappropriate sexual relations, appropriate and inappropriate interactions with faculty members, etc., they will have a much better understanding of how to provide and understand such training when they are in their subsequent business organizations. When taught the kinds of issues concerning students they might visit the university’s ombudsman or call the ethics hotline (a professor has treated them unjustly or asked them to do something inappropriate, or they know that a fellow student is distributing a stolen exam, etc.), they will then be much better equipped to utilize those now common resources in organizations and to develop such resources as business leaders. The sharing of stories regarding university or college ethical dilemmas, failures, and successes, by administrators can also help to strengthen and illustrate such a culture (as developed further in Kiss and Euben 2010: 12).

p.66

When?

At what point in a student’s academic experience is exposure to ethics education most effective? Although Agle and Garff (2015) provide a broad perspective on this question, coming down in favor of exposure throughout the academic experience, the question of the curricular location of the stand-alone ethics course remains an important one. In either undergraduate or graduate education, one can make the argument that the course should be placed toward the beginning of the curriculum as it provides fundamental principles that students should utilize throughout the rest of their coursework. Some might also argue that business ethics cannot really be taught effectively to students who don’t yet understand business fundamentals. Thus, the appropriate approach is probably some hybrid of early exposure with more extensive coverage later in the curriculum.

How?

One could easily spend a lifetime reading the various books and articles on pedagogical approaches to ethics education. Such approaches include lecture (Burton et al. 1991); case studies (Falkenberg and Woiceshyn 2008); exposure to comic books (Gerde and Foster 2008), film (Hosmer and Steneck 1989; Gerde et al. 1996), and literature (Badaracco 2006); personal reflection and self-discovery (Calton et al. 2008); and service-learning (Vega 2007); etc. All of these approaches bring with them strengths as well as limitations. In our experience, we find that the most effective approach tends to be that which best utilizes an instructor’s talents. However, “our experience” is not a particularly satisfying phrase. Thus, we argue again that such questions need to be answered through rigorous large-scale, multi-institutional, multi-instructor, longitudinal research. We renew our call for such efforts. Current efforts to help professors be more effective in their ethics teaching, with particular emphasis on the newer areas of behavioral ethics and Giving Voice to Values, include the following.

1 Business Roundtable Institute for Corporate Ethics in affiliation with the Darden School at the University of Virginia (www.corporate-ethics.org). The Darden School and the Business Roundtable Institute provide an extensive library of written and video materials regarding business ethics by many leaders in the field.

2 Ethics Unwrapped at University of Texas, Austin—this website (ethicsunwrapped.utexas.edu) provides a helpful set of videos explaining concepts in both behavioral ethics and Giving Voice to Values.

3 Giving Voice to Values—this website (www.babson.edu/Academics/teaching-research/gvv/Pages/home.aspx) provides a multi-faceted set of teaching materials related to the Giving Voice to Values curriculum, including cases, videos, readings, corporate examples, etc.

p.67

4 EthicalSystems.org. This collaboration of leading ethics scholars headquartered at the Stern School at NYU provides access to the latest research on organizational ethics.

5 Wheatley Institution Ethics Initiative at BYU (ethics.byu.edu). In concert with the Society for Business Ethics, the Wheatley Institution hosts a bi-annual conference on the teaching of business ethics. These conferences feature leading business ethics professors teaching a favorite business ethics class, providing a model for others to emulate. These exemplary classes are available on the website.

Strengthening a student’s moral sense and commitment

We will now present a case for ways to improve the teaching of business ethics. In teaching such courses, we cannot simply assume that students will have a well-formed ethical sensibility, understanding, or commitment, and, even if they do, it is important to spend time strengthening a student’s moral sense—that is, their sense of right and wrong.6 If we fail to do so and move too quickly to the ethical dilemma stage involving complex cases, we can inadvertently create two undesirable results: 1) students may be led to conceive of business ethics in an exclusively cognitive manner, without a corresponding change in attitude or moral commitment; 2) students may end up thinking that being ethical in business is simply a type of game in which they learn to rationalize whatever they end up doing. This feeds into moral skepticism, moral relativism, and the view that ethical decision-making is merely an exercise in rhetorical skill. It’s not that we must exclude the use of cases or ethical dilemmas at the start of such a course;7 nor does it mean we should not provide students with the essential analytical skills necessary to guide them in dealing with such complex dilemmas. However, it does mean that we ought to present to students a sufficiently strong case that we all have a moral sense, a capacity to recognize certain principles of right and wrong. Furthermore, we need to teach in a way that encourages a stronger moral commitment. In the final section, we will discuss how focusing on moral blindness and self-deception can be one of the most effective ways to engage students.

The approach under consideration here would involve beginning a course by articulating some of the fundamental moral intuitions and principles found in almost all moral theories—for example, that all persons deserve respect and that there are minimal standards in terms of which we all expect others to treat us and which we in turn can be expected to treat others, and so on. The important thing is to articulate claims that most students should find fairly intuitive in order to strengthen their sense that there are universally valid moral principles The point is not that there are easy answers or absolute rules to determine every ethical decision, but rather to show students that there are moral principles that extend beyond individual preference, and across contexts, and can guide us in making such decisions. When we then turn to complex ethical dilemmas, students will more likely be able to navigate difficult decisions without recourse to ethical relativism and skepticism. It is important to present, at first, some of the fundamental insights from different moral teachings and principles in a fairly in-depth manner without simultaneously giving a too-detailed account of different moral systems. Students can easily become bewildered in a maze of moral theories if we go too fast into all the differences among them. However, a hasty overview of various moral theories (for example, simply spending a day covering a one-chapter overview of various moral theories) is also inadequate. We thus need to avoid presenting either a superficial sketch of moral theories—which leaves them with little more than a shallow understanding of ethics—or inundating them further into ethical theory than is needed in a business ethics course. Our argument is that giving students a good grounding in moral philosophy is essential, but that, before doing too much comparing and contrasting of all the different moral theories, it is crucial to find some way to help students come to appreciate that there is non-relativistic discernable status to principles of right and wrong.

p.68

Ethics and self-interest

As part of this approach, it is crucial to help students recognize both that 1) ethics is not based on self-interest, but also that 2) ethics is not necessarily contrary to self-interest. Establishing the first point is especially important in undercutting the move to egoism (or, more precisely, the move to adopting a position of ethical egoism), as well as the varieties of relativism that many students embrace. Business students can be especially attracted to ethical egoism since so much of business seems oriented toward self-interest. There are several ways to support the claim that our ethical systems and judgments are not essentially grounded in self-interest. One way is to point out that immoral or unethical actions are wrong regardless of how they may adversely harm the interests of those who engage in such actions. Take any serious ethical wrongdoing—murder, rape, fraud, and so on. When articulated in the right way, students can readily recognize that such actions are not wrong simply because these acts might harm their own interests in various ways (e.g., by leading to prison, etc.). They are wrong because of what such acts do to others who deserve the respect and regard called for in our fundamental duties not to harm others.

Another way to show that egoism is not the basis of moral action focuses on the implicit objectivity of moral judgments. Thomas Nagel provides an argument based on this approach. He points out that there is an “objective interest” we attribute to many of our needs and desires and that we are able to recognize an “objective element in the concern we feel for ourselves” (Nagel 1970: 83). Such objective interest shows up in the fact that when another person harms us, we not only dislike it, but we resent it (an argument first formulated by Adam Smith in 1759, see 1976: 79–83, 137). In other words, we think that “our plight [gives the other person] a reason” not to harm us. We can then recognize the importance of extending that “objective” status to the interests of others. This implies there are reasons to refrain from harming others (as well as reasons to help others) even when doing so has no apparent influence against or in favor of our own interests.

Here it is helpful (particularly in a business ethics course) to appeal to Adam Smith, who himself argues that ethical normativity cannot be based on self-interest. While it is true that, for Smith, the success of capitalism is based largely on self-interest, this success must come within certain limits on self-interest. In the Wealth of Nations, Smith states that “every man, as long as he does not violate the laws of justice, is left perfectly free to pursue his own interest in his own way, and to bring both his industry and capital into competition with those of any other man” (Smith 1981: 186).8 In a passage from The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Smith writes: “one individual must never prefer himself so much even to any other individual, as to hurt or injure that other, in order to benefit himself, [even] though the benefit to the one [might] be much greater than the hurt or injury to the other” (1976: 138). Smith also refers to this sense of justice as “fair play” (1976: 83). Having a sense of fair play and the moral limits on self-interest are essential for Adam Smith and, arguably, to the success of capitalism.9

Here, it is helpful to make the case to students as to why capitalism cannot work effectively when based merely on self-interest without regard to the ethical limits on self-interest. How are moral limits essential to the success of capitalism? As many have argued, a business cannot truly succeed in the long-term without being ethical. As Robert Solomon puts it, “Though integrity does not guarantee success, there can be no success without it” (Solomon 1993: 174). Solomon adds: “This does not mean that virtue always prospers, but it does mean that the integrity of the corporation and the individual within the corporation is an essential ingredient in the overall viability and vitality of the business world” (21). Thus, while the ethical cannot be grounded simply in self-interest, it is nevertheless true that being ethical is almost always in one’s real interest. As Norman Bowie argues, though conventional wisdom is that business should focus solely on the bottom line, if one does the right thing then profits are likely to result. While this is perhaps not the case in every instance, most often it seems to follow that those who are ethical are those who do very well (as evidenced in Bowie 1999: 23, 132–416). In any case, unethical practices will most likely lead to failure, and long-term success is not likely without an ethical commitment.10

p.69

Avoiding the slide to relativism

Establishing that ethics cannot simply be based on self-interest also helps indirectly to diminish support for normative ethical relativism; even so, it is important to address the issue with students, as well as in sessions devoted to training managers and executives. As Geert Demuijnk has recently argued, “the theoretical framework of cross-cultural management studies that has been the background of most of the teaching, executive training, consultancy” draws heavily on the work of Geert Hofstede and others who explicitly advocate a normative ethical relativism (2015: 824). However, as Demuijnk puts it: “The rejection of relativism and skepticism is a precondition for business ethics to get off the ground” (2015: 819). It is “only if people are convinced that not all ways of doing things are equivalent from a moral perspective [that] genuine discussions of business ethical issues will be taken seriously” (832). As Demuijnk also points out, the topic of ethical relativism is unfortunately neglected by many business ethics textbooks (819). He provides some striking examples to show the problems with ethical relativism (Demuijnk 2015: 828). For example, he shows that it would imply the permissibility of heinous practices that almost everyone would condemn, but also that even when such practices seem to be sanctioned by some culture, we can find those within such a culture who recognize the wrongness of such actions.11

Ethical relativists reject the claim that there are universally valid moral principles. However, as Louis Pojman shows, ethical relativism generates some absurd consequences (Pojman and Fieser 2012). Among other absurd results, if ethical relativism were true, we could not say that Gandhi (or any other moral exemplar) was any better than Hitler (or any other morally reprehensible person). Regarding ethical relativism, Joseph DesJardins (2014) articulates three confusions or “traps” that students can easily fall into. One of these “traps” involves “confusing respect, tolerance, and impartiality with relativism.” As both DesJardins and Pojman point out, if ethical relativism were true, then condemnation of intolerance would simply be opinion and there could be no required universal norm of tolerance. As Pojman puts it, “From a relativistic point of view there is no more reason to be tolerant than intolerant, and neither stance is objectively morally better than the other” (Pojman and Fieser 2012: 21). Furthermore, since this very ideal of tolerance often motivates acceptance of ethical relativism, pointing out that universal tolerance does not logically follow from ethical relativism undercuts one major support for such a view.

The Golden Rule

Another way to strengthen a student’s conviction that there are principles that everyone can accept is to focus on the Golden Rule, which can serve as a powerful tool to help students recognize the objective nature of those interests we share with others. In his essay, “Deception and Withholding Information in Sales,” Thomas Carson illustrates how pedagogically persuasive the Golden Rule can be in teaching business ethics. He argues that there are several prima facie duties in regard to selling products, each based on an appeal to the Golden Rule. For instance, to support the duty to warn customers regarding appropriate safety warnings and precautions for their products, he notes: “No one who values her own life and health can say that she does not object to others failing to warn her of the dangers of products they sell her” (Carson 2010: 171). Such examples present students with an intuitive way to recognize that there are indeed ethical principles relevant to business that they should accept.

p.70

It is essential, however, to formulate properly the Golden Rule since the simplest version is not without problems. As Harry Gensler and others have argued, application of the “literal” version (“do unto others as you would have them do unto you”) can result in absurd consequences (Gensler 2011; Bruton 2004; Burton and Goldsby 2005). Gensler’s revised version, which states, “Treat others as you would consent to be treated in the same situation” avoids most of the problems that the literal version can engender.

Even though it is an almost essential tool in helping students to see the universal nature of ethical principles, the Golden Rule is not the only moral principle we need, and it does have certain limitations. As Samuel V. Bruton notes, the problem with the Golden Rule is that it is based on preferences and wants. Thus, it would seem the Golden Rule would prohibit a business “from raising prices, even when their costs go up, on the grounds that customers would prefer that they not do so” (Bruton 2004: 183), or “prevent employers from firing unproductive employees who wish not to lose their job” (183) because clearly neither the employee nor the employer would want to be fired. It also faces difficulties when multiple stakeholders with different interests are involved. Such limitations in applying the Golden Rule can provide an effective transition to other basic ethical principles.12

One effective ethical principle to supplement the Golden Rule is Kant’s Formula of Humanity as an End: we ought to treat humanity in oneself and in others always as an end, and never merely as a means. As Bruton argues, the imperative to treat the humanity of others as an “end” implies that respecting others’ humanity is a “matter of adhering to standards that they could accept as rational beings.” Conversely, to treat someone merely as a means is to treat that person in “accordance with rules or principles that the other could not reasonably accept” (Bruton 2004: 185). Thus, “Instead of focusing on preferences, the Formula of Humanity as an End relies on the notion of what people could or would accept. Though it is difficult to rigorously characterize “reasonableness,” students should be able to grasp the intuitive difference between what is reasonable and what merely satisfies preference” (185).13 To illustrate how the application of Kant’s principle incorporates judgments that the Golden Rule cannot, Bruton returns to his previous example. He notes that because it would “be unreasonable even for employees not to accept the rule that says businesses may fire inadequate workers, one does not violate their humanity by doing so” (185). Introducing this Kantian principle in this way helps students see the connection between the Golden Rule and other fundamental ethical principles. Even with its limitations, the Golden Rule principle provides one of the best ways to help students appreciate the significantly objective status of ethics.14

Moral blindness, self-deception, and unethical actions

A good business ethics course will not only strengthen students’ recognition that there are principles they should accept as right; it will also educate them on the common forms of self-deception and moral blindness that we tend to engage in when we go against what we know is right. In relation to the 2007 Duke University business school cheating scandal, Terry Price argues:

p.71

In ethics, the general requirements—the what of morality—are often quite straightforward. Indeed we would be hard pressed to find anyone in our society, let alone a university-level student, who was unaware of the general prohibition on cheating. However, the application of these requirements to individuals—the whom of morality—can be significantly murkier. I dare say that it would not be difficult at all to find students who genuinely believe that their circumstances justify them in violating the prohibition on cheating.

(Price 2007)

Moral blindness and self-deception often occur as the individual shifts from a reflection on right and wrong in general to a consideration of right or wrong for me in some particular situation. Thus, it is crucial to alert students to the types of rationalizations and justifications that often prevent us from seeing and acting on what is right in particular situations. Such moral blindness has been an important emphasis in recent years for those doing behavioral business ethics (see De Cremer and Tenbrunsel 2012). In the book Blind Spots, for example, Max Bazerman and Ann Tenbrunsel effectively point out some of the ways we are often influenced by psychological patterns that contribute to unintentional wrongdoing. They refer to such limitations as “bounded ethicality.” As they explain, “most instances of corruption, and unethical behavior in general, are unintentional, a product of bounded ethicality and the fading of the ethical dimension of the problem” (Bazerman and Tenbrunsel 2011: 19). Such bounded ethicality refers to the “cognitive limitations that can make us unaware of the moral implications of our decisions” (30). Articulating these cognitive limitations that generate moral blindness is crucial in the context of business ethics courses and training programs.

As examples of such “bounded ethicality,” Bazerman and Tenbrunsel point to cognitive biases that make us think we are more ethical than we really are (37): overly discounting the future (56), recollection biases (72), as well as the everyday egocentrism that leads us “to make self-serving judgments regarding allocations of credit and blame” (50). Closely related to this phenomenon is the notion of “ethical fading,” which occurs when the ethics of a situation fade, and we interpret the situation under another description—such as a business, or legal decision. According to Bazerman and Tenbrunsel, ethical fading is usually caused by external forces like those that contributed to the Ford Pinto case, in which intense competition led Ford managers to overlook the ethical nature of a decision to prioritize the costs of recalling and replacing fuel tanks over the costs to those who might be harmed by malfunction (36). Another example would be the time pressures surrounding the decisions that led to the Space Shuttle O-Ring disaster (14). But such ethical fading is also influenced by compliance systems (113), rewards systems, one-dimensional goals (107), and pressures from the informal culture of a business (117). Bazerman and Tenbrunsel recommend various strategies to help prevent ethical fading and the effects of bounded ethicality (104–117; 160–163).

Such moral blindness is often due to self-deception. Tenbrunsel and Messick claim that “self-deception is at the core of ethical fading” (2004: 233). Such self-deception either “eliminate[s] negative ethical characterizations or distort[s] them into positive ones” (232). This allows us to disguise “the moral implications of a decision” and thus “behave in a self-interested manner and still hold the conviction that [we] are ethical persons” (225).

One contemporary philosopher, C. Terry Warner, gives a particularly compelling account of how self-deception and moral blindness occur. His account of self-deception and self-betrayal (the foundation for work done by the Arbinger Institute—see Arbinger 2015) argues that self-deception involves distortions for which we are responsible. His emphasis is less on the type of external pressures and psychological patterns that we find in Blind Spots, and more on how some forms of moral blindness are our own creations rather than inevitable consequences of the circumstances. His account provides students with a way to understand both that they are moral agents and that their own actions profoundly influence their moral perception of the world.

p.72

A good business ethics course should do what it can to alert students to the types of self-deception and moral blindness to which we are all susceptible. In our experience, such a focus is one of the best ways to truly engage students and help them internalize the ethical.

Concluding remarks

We began this chapter with a brief overview of the current trends in business ethics education and then presented a case for a pedagogy that strengthens a student’s understanding that ethics is neither based on self-interest nor simply relative to individuals or cultures. Finally, we showed the importance of recognizing common forms of moral blindness and self-deception. This approach responds to the new emphasis being placed on behavioral ethics.

However, there remain issues that need to be considered concerning teaching business ethics. First, since business is increasingly international, an emphasis on international understanding will need to increase. While some have done some very helpful work on international business ethics, there is still more to be accomplished. Clearly, as we have argued in this chapter, there are universal principles that should apply internationally. Nevertheless, there are still many questions to be answered concerning how to apply basic moral principles in cultures that differ from our own. What, for example, does respect require of us in the face of different traditions?

Second, the field needs to do a much better job of assessing the effectiveness of ethics teaching. While there are many short-term studies, there is a dearth of longitudinal studies looking at various groups, and different types of educational interventions (type of curricula, type of educational institutions, etc.). These studies are badly needed, yet are expensive in terms of both time and money, and require significant commitment on the part of researchers.

Essential works

Essential works on business ethics education include Thomas R. Piper, Mary C. Gentile and Sharon D. Parks, Can Ethics Be Taught? (1993), Ronald R. Sims, Teaching Business Ethics for Effective Learning (2002), and Mary C. Gentile, Giving Voice to Values (2010). For newer collected works on the subject, see Diane Swanson and Dann Fisher (eds), Advancing Business Ethics Education (2008), Charles Wankel and Agata Stachowicz-Stanusch (eds), Management Education for Integrity (2011), and Diane Swanson and Dann Fisher (eds), Got Ethics? Toward Assessing Business Ethics Education (2011). Broader works that deal with moral education in business schools and universities include Rakesh Khurana, From Higher Aims to Hired Hands (2007), Elizabeth Kiss and J. Peter Euben (eds), Debating Moral Education (2010), and Derek Bok, Our Underachieving Colleges (2006).

For further reading in this volume on the aims and objectives of business ethics education, see Chapter 3, Theory and method in business ethics. On education and moral blindness in management, see Chapter 27, The ethics of managers and employees. For a discussion of moral myopia in marketing, see Chapter 30, Ethical issues in marketing, advertising, and sales. On theoretical perspectives in ethics see the selection of chapters in Part II: Moral philosophy and business: foundational theories. Further discussion of business ethics and education (and the idea of business as a profession) may be found in Chapter 11, Stakeholder thinking. On Geert Hofstede, cross-cultural management, and relativism, see Chapter 32, The globalization of business ethics.

p.73

Notes

1 Weber (2015) found that 70 out of 71 large US-based global corporations contacted had ethics training programs in place. Seventy percent of top business schools have an ethics requirement, and 57 percent require at least one stand-alone ethics course (Litzky and MacLean 2011).

2 As Kiss and Euben point out, “A more complex understanding of moral development has led to a tendency to replace a singular emphasis on moral reasoning with models of moral education that combine cognitive, affective, volitional, and behavioral capacities.” See Kiss, E. and Euben, J. (eds) (2010: 11).

3 We will return to a discussion of ethical fading in a later section of this chapter.

4 “Moral disengagement” includes distorting consequences, euphemistic language, and advantageous comparison.

5 “Neutralization techniques” refers to the way one justifies wrongdoing through a denial of the victim, denial of injury, along with an appeal to higher loyalties, etc.

6 When we use the term “moral sense,” we are not endorsing any particular meta-ethical position (e.g., any particular position on a “moral sense,” as did some philosophers of the eighteenth century—Francis Hutcheson is the chief example). We intend a broad use of the term that could apply to most moral theories ranging from that of Aristotle, with his notion of practical reason, to that of Kant, with his concept of moral reason.

7 For a good discussion of using the case method, see Goodpaster 2002.

8 See also Smith 1981[1776], pp. 82–3. It is worth noting that Smith’s notion of self-interest is not necessarily a narrow one, but would likely include one’s small circle of family and friends.

9 For excellent sources on Adam Smith on self-interest and business, see Heath (2013), Bragues (2010), and Solomon (1993).

10 Joseph DesJardins points to the Malden Mills case as evidence that being ethical does not always lead to success (DesJardins 2014).

11 One example Demuijnk gives is that of an Amazon tribe (the Suruwaha) that buries children alive if they have some physical defect (because they think they have no souls). He points to a report in which a family went to great lengths to avoid complying with an order to kill their child as evidence that people within that culture recognized the wrongness of such actions.

12 It is possible that Gensler’s formulation of the Golden Rule can address such concerns. However, this is a debate for another time.

13 Of course, some moral philosophers (for example, David Hume or Thomas Hobbes) accept only an instrumental conception of reason. On such views, this point would be more difficult to make. Kant, among many other moral philosophers, does not accept such an instrumental notion of reason.

14 There are many other ways one might strengthen a student’s recognition that there are common moral principles. Another approach might focus on W.D. Ross’s account of prima facie duties. Robert Audi (2009) illustrates the effectiveness of this approach.

Bibliography

Abend, G. (2014). The Moral Background: An Inquiry into the History of Business Ethics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Agle, B.R. and T. Crossley (2011). “Business Ethics Education, Why Bother? Objectives, Pedagogies, and a Call to Action,” Proceedings of the Conference on Leveraging Change—The New Pillars of Accounting Education, Toronto.

Agle, B.R. and P. Garff (2015). “Matching Business Ethics Education Objectives and Pedagogy: Utilizing the Entire University Experience in Creating Stronger Moral Agents,” Working Paper.

Agle, B.R., D.W. Hart, J.A. Thompson, and H. Hendricks (eds) (2014). Research Companion to Ethical Behavior in Organizations: Constructs and Measures. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Arbinger (2015). Leadership and Self-Deception, 2nd edition. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Ariely, D. (2012). The Honest Truth about Dishonesty. New York, NY: Harper-Collins.

Armstrong, M.B., J.E. Ketz, and D. Owsen (2003). “Ethics Education in Accounting: Moving Toward Ethical Motivation and Ethical Behavior,” Journal of Accounting Education 21:1, 1–16.

Audi, R. (2009). Business Ethics and Ethical Business. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Badaracco, J. (2006). Questions of Character. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Bandura, A. (1999). “Moral Disengagement in the Perpetration of Inhumanities,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 3:3, 193–209.

p.74

Bazerman, M.H. and A.E. Tenbrunsel (2011). Blind Spots: Why We Fail To Do What’s Right and What To Do About It. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Berenbeim, R. (2013). “Ethics Classes Don’t Need to Make Students More Ethical To Be Worthwhile.” Available at: www.ethicalsystems.org/content/ethics-classes-don’t-need-make-students-more-ethical-be-worthwhile.

Boatright, J. (2012). Ethics and the Conduct of Business, 7th edition New York: Pearson.

Bok, D. (2006). Our Underachieving Colleges. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bowie, N. (1999). Business Ethics: A Kantian Perspective. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Bragues, G. (2010). “Adam Smith’s Vision of the Ethical Manager,” Journal of Business Ethics 90, 447–460.

Burton, B.K. and M. Goldsby (2005). “The Golden Rule and Business Ethics: An Examination,” Journal of Business Ethics 56:371–383.

Burton, S., M.W. Johnston and E.J. Wilson (1991). “An Experimental Assessment of Alternative Teaching Approaches for Introducing Business Ethics to Undergraduate Business Students,” Journal of Business Ethics 10:7, 507–517.

Bruton, S. (2004). “Teaching the Golden Rule,” Journal of Business Ethics 49:2, 179–187.

Calton, J., S. Payne and S. Waddock (2008). “Learning to Teach Ethics from the Heart,” in Swanson, D. and Fisher, D., Advancing Business Ethics Education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Carlson, P.J. and F. Burke (1998). “Lessons Learned From Ethics in the Classroom: Exploring Student Growth in Flexibility, Complexity and Comprehension,” Journal of Business Ethics 17, 1179–1187.

Carroll, A. (2005). “An Ethical Education,” BizEd 4:2, 36–40.

Carson, T. (2010). Lying and Deception. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ciulla, J.B. (2011). “Is Business Ethics Getting Better? A Historical Perspective,” Business Ethics Quarterly 21:2, 335–343.

Collins, D. (2012). Business Ethics: How to Design and Manage Ethical Organizations. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Culham, T. (2013). Ethics Education of Business Leaders. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

De Cremer, D. and A. Tenbrunsel (2012). Behavioral Business Ethics: Shaping an Emerging Field. New York: Routledge.

Demuijnk, G. (2015). “Universal Values and Virtues in Management Verses Cross-Cultural Relativism: An Educational Strategy to Clear the Ground for Business Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 128, 817–835.

DesJardins, J. (2014). An Introduction to Business Ethics. New York: McGraw Hill.

Donaldson, T., P. Werhane and J. Van Zandt (2007). Ethical Issues in Business: A Philosophical Approach, 8th edition New York: Pearson.

Duska, R. (1991). “What’s the Point of a Business Ethics Course?” Business Ethics Quarterly 1:4, 335–354.

Duska, R. (2014). “Why Business Ethics Needs Rhetoric: An Aristotelian Perspective,” Business Ethics Quarterly 24:1, 119–134.

Earley, C.E. and P.T. Kelly (2004). “A Note on Ethics Educational Interventions in an Undergraduate Auditing Course: Is There an ‘Enron Effect’?” Issues in Accounting Education 19:1, 53–71.

Elkjaer, B. (2003). “Social Learning Theory: Learning as Participation in Social Processes,” in Mark Easterby-Smith and Marjorie Lyles (eds), The Blackwell Handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management. Malden, MA and Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, 38–53.

Falkenberg, L. and J. Woiceshyn (2008). “Enhancing Business Ethics: Using Cases to Teach Moral Reasoning,” Journal of Business Ethics 79:3, 213–217.

Garrod, A. (ed.). (1993). Approaches to Moral Development: New Research and Emerging Themes. New York: Teachers College Press.

Gautschi, F.H. and T.M. Jones (1998). “Enhancing the Ability of Business Students to Recognize Ethical Issues: An Empirical Assessment of the Effectiveness of a Course in Business Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 17:2, 205–216.

Gensler, H. (2011). Ethics: A Contemporary Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Gentile, M. (2010). Giving Voice to Values. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gerde, V.W. and R.S. Foster (2008). “X-men Ethics: Using Comic Books To Teach Business Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 77:3, 245–258.

Gerde, V.W., J.M. Shepard, and M.G. Goldsby (1996). “Using Film to Examine the Place of Ethics in Business,” Journal of Legal Studies 14:2, 199–214.

Gino, F., M.E. Schweitzer, N.L. Mead and D. Ariely (2011). “Unable To Resist Temptation: How Self-control Depletion Promotes Unethical Behavior,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 115:2, 191–203.

p.75

Glenn, J. (1992). “Can a Business and Society Course Affect the Ethical Judgment of Future Managers?” Journal of Business Ethics 11:3 (March), 217–223.

Goodpaster, K.E. (2002). “Teaching and Learning Ethics by the Case Method,” in N. Bowie (ed.), The Blackwell Companion to Business Ethics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 117–141.

Grant, A.M. and F. Gino (2010). “A Little Thanks Goes a Long Way: Explaining Why Gratitude Expressions Motivate Prosocial Behavior,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 98:6, 946.

Greene, J.D., R.B. Sommerville, L.E. Nystrom, J.M. Darley and J.D. Cohen (2001). “An fMRI Investigation of Emotional Engagement in Moral Judgment,” Science 293:5537, 2105–2108.

Greene, J. and J. Haidt (2002). “How (and Where) Does Moral Judgment Work?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6:12, 517–523.

Haidt, J. (2014). “Can You Teach Businessmen to be Ethical?” Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/on-leadership/wp/2014/01/13/can-you-teach-businessmen-to-be-ethical/.

Hartman, E. (2006). “Can We Teach Character? An Aristotelian Answer,” Academy of Management Learning and Education, 5:1, 68–81.

Hartman, E. (2013). Virtue in Business: Conversations with Aristotle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hartman, L and J. DesJardins (2011). Business Ethics: Decision Making for Personal Integrity and Social Responsibility, 2nd edition. New York: McGraw Hill.

Hasnas, J. (2013). “Teaching Business Ethics: The Principles Approach,” Journal of Business Ethics Education 10, 275–304.

Heath, E., B. Hutton, D. McAlister, J. Petrick and S. True (2005). “Panel: Philosophies of Ethics Education in Business Schools,” Journal of Business Ethics Education 2:1:13–20.

Heath, E. (2013). “Adam Smith and Self-Interest,” in C.J. Berry, M.P. Paganelli and C. Smith (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Adam Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 241–264.

Hosmer, L.T. and N.H. Steneck (1989). “Teaching Business Ethics: The Use of Films and Videotape,” Journal of Business Ethics 8:12, 929–936.

Kant, I. (1994). Ethical Philosophy, J.W. Ellington (trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Hackett.

Khurana, R. (2007). From Higher Aims to Hired Hands. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kiss, E. and J. Euben (eds) (2010). Debating Moral Education. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Langlois, L. and C. Lapointe (2010). “Can Ethics be Learned? Results From a Three-Year Action-Research Project,” Journal of Educational Administration 48:2, 147–163.

Lau, C.L. (2010). “A Step Forward: Ethics Education Matters!” Journal of Business Ethics 92:4, 565–584.

LeClair, D.T., L. Ferrell, L. Montuori and C. Willems (1999). “The Use of Behavioral Simulation to Teach Business Ethics,” Teaching Business Ethics 3, 283–296.

Litzky, B.E. and T.L. MacLean (2011). “Assessing Business Ethics Coverage at Top U.S. Business Schools,” in D.L. Swanson and D.G. Fisher (eds), Toward Assessing Business Ethics. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 133–142.

Mason, R.G. (2008). “Considering the Emotional Side of Business Ethics,” in D.L. Swanson and D.G. Fisher (eds), Advancing Business Ethics Education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

May, D.R., M.T. Luth and C.E. Schwoerer (2014). “The Influence of Business Ethics Education on Moral Efficacy, Moral Meaningfulness, and Moral Courage: A Quasi-Experimental Study,” Journal of Business Ethics 124:1, 67–80.

Mayhew, B.W. and P.R. Murphy (2009). “The Impact of Ethics Education on Reporting Behavior,” Journal of Business Ethics 86:3, 397–416.

McLean, B. and J. Nocera (2010). All the Devils are Here. New York: Portfolio/Penguin.

Morris, L. and G. Wood (2011). “A Model of Organizational Ethics Education,” European Business Review 23:3, 274–286.

Nagel, T. (1970). The Possibility of Altruism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Nagel, T. (2013). “You Can’t Learn About Morality from Brain Scans: The Problem with Moral Psychology,” The New Republic, Nov 1.

Piper, T.R., M.C. Gentile and S.D. Parks (1993). Can Ethics Be Taught? Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

Pojman, L. and J. Fieser (2012). Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Price, T. (2007). “How to Teach Business Ethics,” Inside Higher Education, June 4.

Rasche, A., D.U. Gilbert and I. Schedel (2013). “Cross-Disciplinary Ethics Education in MBA Programs: Rhetoric or Reality,” Academy of Management Learning and Education 12:1, 71–85.

Rest, J.R. (1986). Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory. Toronto: Praeger Publishers.

Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002). PL 107-204, United States Statutes 116 Stat 745.

p.76

Shaw, W. and V. Barry (2013). Moral Issues in Business. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Simha, A., J.P. Armstrong and J.F. Albert (2012). “Attitudes and Behaviors of Academic Dishonesty and Cheating—Do Ethics Education and Ethics Training Affect Either Attitudes or Behaviors?” Journal of Business Ethics Education 9, 129–144.

Sims, R.R. (2002). Teaching Business Ethics for Effective Learning. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Sims, R.R. and E.L. Felton, Jr. (2006). “Designing and Delivering Business Ethics Teaching and Learning,” Journal of Business Ethics 63, 197–312.

Smith, A. (1976 [1759]) in D.D. Raphael and A.L. Macfie (eds), The Theory of Moral Sentiments. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Smith, A. (1981 [1776]) in R.H, Campball, A.S. Skinner and W.B. Todd (eds), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, 2 vols. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Smith, C. (2011). Lost in Translation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Solberg, J., K.C. Strong, and C. McGuire, Jr. (1995). “Living (Not Learning) Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 14, 71–81.

Solomon, R. (1993). Ethics and Excellence: Cooperation and Integrity in Business. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sonenshein, S. (2007). “The Role of Construction, Intuition, and Justification in Responding To Ethical Issues at Work: The Sensemaking-Intuition Model,” Academy of Management Review 32:4, 1022–1040.

Stanwick, P. and S.D. Stanwick (2013). Understanding Business Ethics. New York: Prentice Hall.

Swanson, D. and D. Fisher (eds) (2008). Advancing Business Ethics Education. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

Swanson, D. and D. Fisher (2011). Got Ethics? Toward Assessing Business Ethics Education. Charlotte, Information Age Publishing.

Sykes, G.M. and D. Matza (1957). “Techniques of Neutralization: A Theory of Delinquency,” American Sociological Review 22, 664–670.

Tenbrunsel, A. and D.M. Messick (2004). “Ethical Fading: The Role of Self-Deception in Unethical Behavior,” Social Justice Research 17:2, 223–236.

Treviño, L. and K. Nelson (2010). Managing Business Ethics: Straight Talk about How to Do It Right, 5th edition. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Van Buren, H. and B. Agle (1998). “Measuring Christian Beliefs that Affect Managerial Decision-making: A Beginning,” International Journal of Values Based Management 11:2, 159–177.

Vega, G. (2007). “Teaching Business Ethics Through Service Learning Metaprojects,” Journal of Management Education 31:5, 647–678.

Verschoor, C. (2006). “IFAC Committee Proposes Guidance for Achieving Ethical Behavior,” Strategic Finance 88:6, 19.

Wankel, C. and A. Stachowicz-Stanusch (2011). Management Education for Integrity. Bingley, UK: Emerald Publishing.

Waples, E.P., A.L. Antes, S.T. Murphy, S. Connelly, and M.D. Mumford (2009). “A Meta-Analytic Investigation of Business Ethics Instruction,” Journal of Business Ethics 87:1, 133–151.

Warner, C.T. (2013). Oxford Papers. Farmington, UT: The Arbinger Institute.

Warren, R.C. (1995). “Practical Reason in Practice: Reflections on a Business Ethics Course,” Education and Training 37:6, 14–22.

Weaver, G.R. and B.R. Agle (2002). “Religiosity as an Influence on Ethical Behavior in Organizations: A Theoretical Model and Research Agenda,” Academy of Management Review 27:1, 77–97.

Weaver, G.R. and L.K. Treviño (1999). “Attitudinal and Behavioral Outcomes of Corporate Ethics Programs: an Empirical Study of the Impact of Compliance and Values-Oriented Approaches,” Business Ethics Quarterly 9:2, 315–335.

Weber, J. (1990). “Measuring the Impact of Teaching Ethics to Future Managers: A Review, Assessment, and Recommendations,” Journal of Business Ethics 9:3, 183–190.

Weber, J. (2015). “Investigating and Assessing the Quality of Employee Ethics Training Programs Among US-Based Global Organizations,” Journal of Business Ethics 129:1, 27–42.

Williams, S.C. and T. Dewett (2005). “Yes, You Can Teach Business Ethics: A Review and Research Agenda,” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 12, 109–120.

Wurthmann, K. (2013). “A Social Cognitive Perspective on the Relationships Between Ethics Education, Moral Attentiveness, and PRESOR,” Journal of Business Ethics 114:1, 131–153.