p.204

Alexander Lorch and Thomas Beschorner

Initially developed by Jürgen Habermas1 and Karl-Otto Apel2, discourse ethics remains one of the most influential critical theories of the twentieth century. Habermas’ book The Theory of Communicative Action (1981) and his later Remarks on Discourse Ethics (1991/1992, 1993)3 describe how his ethical theory does not instruct people “upon what they decide but how they come to these decisions” (our emphasis, Baert 2001: 85) in fair conditions of discourse. This differentiation between “what” and “how” points to two important streams in normative ethics: material ethics on the one hand and formal or process-oriented ethics on the other hand. Material ethics tells us what to do, one example of which is the Ten Commandments of Christian ethics. These commandments set forth ethical norms: “Thou shalt not kill” or “Thou shalt not steal.” Process-oriented approaches in ethics, such as discourse ethics, do not focus primarily on concrete moral norms, but on the procedures that yield normative principles. Kantian ethics offer a good example: employ the categorical imperative in order to consider which acts are one’s genuine moral duties.

The same is true for discourse ethics. Here, moral norms are approached by first invoking the moral principle of open debate among equal citizens in which fair processes of deliberation take place in a power-free realm. In opposition to both Christian and Kantian ethics, discourse ethicists reclaim a modernized approach to ethics. It is not a “God given” moral law within us that we should follow, but a moral principle emergent from within the interaction of concrete citizens. In other words, Habermas and others ask: How can we organize a society that enables open discourse and open criticism as the precondition for just practices (moral norms)? With respect to deliberations and open discourses, another key component of Habermas comes into play: “communicative actions,” as opposed to strategic actions. Strategic actions are characterized by power-relations and a process of negotiation and exchange between two or more parties (as we know from economics), but “ideal communication communities” base their interaction on a fair and power-free discourse. Actors do not negotiate, they deliberate.

This general philosophical background has relevance to business ethics. Several authors have made use of discourse ethics while applying it to the economic context and to businesses. These examples include Darryl Reed (1999a, 1999b) with respect to normative stakeholder theories; Thomas Beschorner (2006) with respect to organizational issues; Dirk Ulrich Gilbert and Andreas Rasche (2007) on the question of social standards; John Mingers and Geoff Walsham (2010) on ethical information systems; Gilbert and Michael Behnam (2009) with a perspective on “advancing integrative social contracts theory”; and, most prominently in the international debate, Andreas Georg Scherer and Guido Palazzo (2007), on a “political conception of corporate responsibility . . . from a Habermasian perspective.”

p.205

In this chapter we will outline another discourse ethical approach in business ethics, Integrative Economic Ethics (Ulrich 2008a, 1997). Developed by Peter Ulrich, a philosopher and professor emeritus at the University of St Gallen (Switzerland), Integrative Economic Ethics is currently less present in the international debate than the parallel contributions mentioned above. However, although Ulrich’s ideas might have attracted little international attention in the English-speaking world, his work is extraordinarily influential within the business ethics communities of German-speaking countries. The deep theoretical grounding of Ulrich’s perspective warrants a closer examination. First, Integrative Economic Ethics is not only an application of discourse ethics to the business world, but an attempt to challenge economic rationality on the basis of communicative action. Second, the “transformation” of an instrumental (calculative) rationality into a communicative rationality allows Ulrich to develop a moral point of view that allows him to criticize mainstream economic theory. Third, Ulrich’s theory is not merely a (narrow) view of business ethics but it includes multiple levels of economic and ethical analyses: a micro level of individual ethics, a meso level of the corporation, and a macro level of political regulations.

In five sections we discuss salient elements of Integrative Economic Ethics. We will first discuss Ulrich’s term “integrative” and his understanding of integrative ethics in opposition to “applied ethics.” Based on Ulrich’s understanding of business ethics as a mode of “economic enlightenment” we will then sketch, in section two, the different “loci” of responsibility (micro, meso, and macro) in the concept of Integrative Economic Ethics. We will then further illustrate Ulrich’s approach by employing these three loci. In the third section we discuss the micro level (the individual’s rights and responsibilities), then turning, in the next section, to the meso level of businesses, noting in particular Ulrich’s perspectives on stakeholder management. In a fifth section we provide an account of the macro level of political regulation at which Ulrich urges a form of republican liberalism that connects to ideas of a social market economy, as developed after World War II by German “ordoliberals.” The concluding remarks outline some strengths and weaknesses of Integrative Economics Ethics and sketch possible further research perspectives.

Integrative versus applied ethics

Over the past 25 years Peter Ulrich has developed an impressive oeuvre that constitutes a general theory of business ethics based on discourse ethical ideas. In his earliest book, The Firm as Quasi-Public Institution (1977), Ulrich takes a critical stand on methodological ideas in management sciences. A stronger orientation toward ideas of discourse ethics later enabled him to work out a fruitful conception of business ethics (Ulrich 1993, 1997, 2000; Ulrich and Breuer 2004) that he called Integrative Economic Ethics.4 With its systematic and comprehensive philosophical foundation it serves as an all-encompassing guide to philosophical considerations regarding the nature of a just economy, as well as offering assessments of contestable claims of mainstream economic theory, including the premise of economic rationality. In sum, Ulrich offers a holistic approach to discussing questions of business and ethics.

Integrative Economic Ethics is a rather unconventional appellation, so it is important to understand what is expressed by both terms, “integrative” and “economic ethics.” The theory is called “economic ethics” to convey the fact that it discusses economic actors (i.e., business firms or individual managers) in terms of conventional categories of business ethics (e.g., legitimacy, responsibility, permissibility, and so on), even as it situates the discussion in a broader, holistic, approach to ethics and economic thought. Ulrich’s main statement, laid out in his two major works (Ulrich 1993, 2008a) and countless papers, is that the underlying logic of the market and the way we think about economic policy and business decisions are all imbued with normative claims. It is therefore not sufficient to talk about ethical actions or decisions in a business setting if we do not also critically discuss the larger normative context in which these decisions are embedded. Integrative Economic Ethics therefore discusses first and foremost the underlying normative assumptions of economics, such as “good” market practices, efficiency and the rationality of markets (including, for example, the imperatives of market growth, profit maximization, the necessity of competition, and so on). The chief task of ethics in this context is to “enlighten” and critically reflect on the normative foundations of the inherent logic of the market as a foundation for economic ethics.

p.206

Ulrich’s terminology draws upon an established category utilized in German-speaking debates on economic ethics: “Wirtschaftsethik” is a general term that encompasses all questions related to economic ethics. Questions of economic ethics are then discussed in various sub-fields, labeled institutional or regulatory ethics (“Ordnungsethik”—i.e., questions of economic policy and regulations), business ethics (“Unternehmensethik”—questions of business conduct, corporate social responsibility, corporate citizenship, etc.), and individual ethics (“Individualethik”—questions of consumer ethics, leadership ethics, virtues, etc.). These categories are important for understanding Ulrich’s aim: to establish a universal moral point of view that gives a unified perspective for all questions that touch upon economic settings or arrangements, thereby providing an “ethically rational orientation in politico-economic thinking without abandoning reflection in the face of the implicit normativity of ‘given’ economic conditions.” (Ulrich 2008a: 3–4, emphasis added)

The point of departure for Ulrich is the specific moral point of view laid out in Kantian ethics; this perspective is to be used in all economic considerations. The headline of the introduction to Peter Ulrich’s book Integrative Economic Ethics (2008a) offers to give “orientation in economic-ethical thinking.” This caption, which alludes to Immanuel Kant’s famous essay, “What Does it Mean to Orient Oneself in Thinking?” (Kant 1786), implies that the first intent and general direction of Integrative Economic Ethics is to discuss ethical questions of business and society in a foundational philosophical manner that will, thereby, offer an ethical orientation, a perspective that prioritizes critical moral reasoning shorn of interests and partialities.

Ulrich spends a considerable effort to lay down a thorough clarification of the moral point of view,5 set within a Kantian understanding of rational autonomy. He states that a moral point of view can be grounded only within the self-critical reason of man. Ulrich thus adopts the Kantian perspective as “a moral point of view that all people can recognize as valid and binding because it is rationally well founded” (Ulrich 2008a: 37). This moral point of view is then further developed, in discourse ethics, from an individual moral point of view (Kant) to an interpersonal and formal process of reasoning according to which questions of legitimacy are to be resolved in ideal communication communities (cf. Habermas 1981), as characterized briefly in the opening paragraphs of this chapter.

Once established, this moral point of view is used in two major ways. It is used, first, to illuminate and critically discuss the normative assumptions of economic theory and practice, offering thereby an alternative view on the benefits and drawbacks of the logic of markets, competitiveness, and other axioms of economics. In this way, the moral point of view orients our economic and ethical reasoning. Such orientation not only suggests how to act in a given setting but it also provides legitimacy: According to discourse ethical assumptions, legitimacy stems from deliberation and consensus, not from the adherence to an axiom of economic theory or principle of conduct. Thus, Ulrich’s Integrative Economics Ethics offers, along with his critique of economic reason, a critical discussion of utilitarian ethics as the foundation for economic theory (both in micro- and macroeconomics), at least as it is reflected in appeals to the “greatest happiness of the greatest number,” or to corollary claims concerning the maximization of wealth, profits, or need fulfillment. In this way, Integrative Economic Ethics can be comprehended, in part, as an exercise in “economic enlightenment” attained through discussion and critique of these and other moral or economic assumptions.

p.207

Second, following his critique of economic theory, Ulrich’s moral point of view is used to establish a different, and more appropriate, foundation for an ethically sound economy. Ulrich contends that the moral point of view, as he understands it, should legitimate an understanding of a liberal-republican polity based on Kantian republicanism and the discursive lifeworld (‘Lebenswelt’). Such an approach partakes from both Habermas’s thought and Rawls’ (1999) conception of political liberalism and his theory of justice (see below). Amongst other things, this approach has led to a republican understanding of businesses as citizens, a perspective that has sparked intense debates of corporate citizenship in German business ethics.

The term “integrative” is meant to differentiate this approach further from traditional methods of applied ethics. Integrative Economic Ethics is not meant as an addition or supplement to economic rationality, nor is it set forth as but an alternative perspective to common business decisions (as if it were just another department next to accounting or marketing). For Ulrich, ethics is integrative, present in every single human action and thought, hence also in every economic action and economic thought. For Ulrich, serious (business) ethics can thus be established only by an unconditional critical (self-) reflection of normative economic assumptions. It is henceforth “not enough simply to ‘apply’ ethics to the sphere of economic activity as the alternative to or corrective for economic rationality” (Ulrich 2008a: 3). Integrative Economic Ethics must rather be an integral part of all economic thinking, business actions, and policymaking.

Discourse, legitimization, and responsibility

As we have seen above, Peter Ulrich aims to develop a moral point of view that provides the basis and justification for concrete actions in businesses. Following Habermas, Ulrich’s main idea is to prioritize the idea of fair and power-free discourses. As a consequence, he criticizes an unscrutinized dominance of market economies in modern societies. Such societies are based on two crucial pillars: property rights and the free exchange of properties. Nonetheless, Ulrich does not regard property rights, per se, as problematic; they become problematic only if private economic actions lead to negative (intended or unintended) consequences or side effects. Consequently, Ulrich characterizes firms as quasi-public institutions (Ulrich 1977). Whether listed as corporations or small family businesses, firms are privately owned, but their business activities (can) result in negative external effects for the whole society as many past and recent business scandals have shown. In other words, due to negative external effects (social or ecological), not to mention limitations of the classical nation state to regulate these effects on a constitutional level, businesses increasingly need to legitimate their economic activities. It is important to note here that Ulrich is trying to make a case for ethics (and not for business success). He is not interested in the practical question of how businesses can gain or regain legitimacy merely in order to increase their reputation (the “business case”) but in a practical question of conduct: What is the right thing to do?

p.208

On a theoretical level, Ulrich regards the main problems of modern economics as its underlying orientation toward a calculative or utilitarian ethics. In contrast, Ulrich suggests, economics should be grounded on communicative ethics; it needs to be transformed from an economic into a socioeconomic rationality: “Any action or institution is rational in a socioeconomic sense if free and responsible citizens could have consensually justified it as a legitimate way of creating value in a rational process of deliberation” (Ulrich 2002: 19, emphasis added). This explication of the moral point of view indicates that individual interests should not be followed if there is no general agreement on them in a given discourse community—that is, if they are not legitimate. Rational moral discourse (the legitimacy of actions) precedes any rational decision in an economic sense (utility or profit maximization) (Ulrich 1997: 13, 2000).

This normative component is not taken into account in economics since economic rationality is “purely” based on the normative logic of the exchange of benefits. In contrast, Ulrich stresses, as does Habermas, categorical orientations toward normative principles: One should act on a principle because the principle is understood to be right. In other words, Ulrich attempts to work out “regulative ideas” of businesses as (corporate) citizens rather than regarding them simply as “pure” economic actors within an economic system. He especially emphasizes “normative logics of human interaction” that are “justice-based” rather than power-based, and that are grounded on “intersubjective obligations” rather than maximizing private interests (Ulrich 2002: 21).

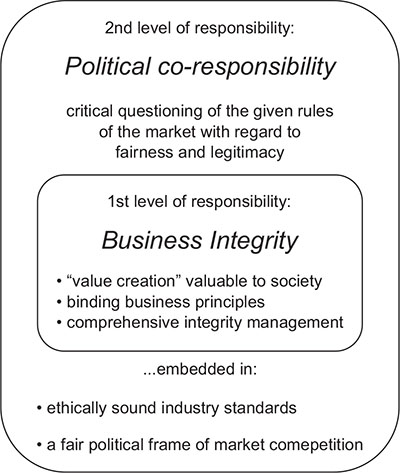

With regard to a first concrete “application” of the concept of integrative business ethics, Ulrich distinguishes different loci of socioeconomic responsibility: On the constitutional (macro) level, he follows the social market system adumbrated by the school of ordoliberalism and he embraces, as well, the so-called concept of Vitalpolitik (“policies aimed at ‘vital’ prerequisites for a good life”). With a parenthetical reference to Wilhelm Röpke, one of the major architects of postwar “ordoliberalism,” Ulrich proposes the (re-)embeddedness of the market economy “into a higher overall order, which cannot be based on supply and demand, free prices and competition” (Ulrich 2002: 29). In addition and complementary to a political-economic framework, Ulrich develops a corporate ethics, with at least two important elements: at the first level a demand for corporate social responsibility (or, as Ulrich puts it, “business integrity”); at the second level, a call to the “political co-responsibility” of firms. Figure 12.1, on the next page, reproduces both elements.

Business integrity includes the search for legitimate value creation, so this pursuit is, in this sense, a legitimate practice to find business opportunities: “Thus, a possible synthesis between ethics and economics (“the business case”) is not criticized per se but it is rather seen as valuable for the firm and society” (Ulrich 1994: 93–94, 1996). However, Ulrich makes it clear that business practices must be grounded in deontological values that subject business strategies to the light of moral principles. In other words, individuals and firms should be bound, by moral necessity, to certain “good” business principles.

p.209

This idea can be illustrated with a simple example: Let us assume corruption and bribery are seen as immoral practices of businesses, and let us also assume, further, that company X shares this understanding and has included a non-corruption policy in its statement of corporate values. In the hypothetical scenario in which bribery of a public official appears as an option, the corporation could determine what to do by adopting a strict business case perspective and undertaking a cost-benefit calculation (e.g., how big is the contract, what is the likelihood that the bribery will be discovered?) to determine what to do. But such a perspective (and such a calculation) might direct the firm towards morally questionable acts. However, from Ulrich’s perspective, the company could under no circumstances make such a deal; no matter how big this business is or how unlikely it is to be caught. Business integrity demands a broader perspective, including a categorical adherence to deontological values.

The level of political co-responsibility of firms in Ulrich’s concept of corporate ethics is linked with the above-mentioned idea of embeddedness and corporate citizenship. For Ulrich, the social responsibility of businesses is related to their contributions to just institutions on a political level. Businesses should not merely act according to the rules of the game but ought to be “game changers” through active political participation as corporate citizens (for more details see below). The commitment and engagement of companies to develop ethically sound standards within their industries or their participation in multi-stakeholder initiatives are important examples of the political co-responsibility of firms. Such co-responsibility should involve the search for legitimate collective solutions and an approach to business ethics that is not limited to the “internal” CSR performance of a company.

Neither the constitutional level nor one of the two levels in Ulrich’s corporate ethics are, however, the main loci of fairness. Suitable political arrangements and corporate ethics assist in the realization of justice in modern societies, but they do not have an independent moral status—they do not function, so to speak, as “moral judges.” After all, the crucial element in Peter Ulrich’s republican business ethics is the critical public. Ulrich does not build his ethical approach on a set of material norms, by which we are to render judgments, but on a formal principle of discussion and deliberation. Habermas’ “ideal speech situation” is the yardstick to measure the circumstances of “real communication.” It represents an ideal type of open debate for all and without any constraints (Baert 2001: 88).

To grasp more fully how Ulrich’s ethics might be “applied” to the three levels of responsibility, we turn first to the micro level of the individual. As noted above, and as we see below, Integrative Economic Ethics is less a technique to be applied than a normative orientation.

p.210

The micro level: the ethics of economic citizens

Integrative Economic Ethics imbues the question of a political order with the specific perspectives of citizens and their civic virtues. Ulrich conceives of society as (striving for) a free and democratic political order based on liberal principles. In accordance with the Kantian moral point of view,

interpersonal obligations can be founded only on the observation of the same inviolable freedom of all men in the sense of their right to pursue the ‘possibility of human existence’ to the full. This is in accordance with the autonomous personal commitment of every moral subject to the conditions of the general freedom of all men.

(Ulrich 2008a: 14)

This general freedom of all men then necessarily leads to a liberal political framework that Ulrich calls Republican Liberalism, linking it to the political liberalism proposed by Rawls (1999) but drawing upon fruitful discussions between liberalism and communitarianism (see, for example, Honneth 1993; Forst 2002), while also adding important elements of republicanism (Pettit 1997). For Ulrich, individual freedom is understood chiefly as positive freedom (cf. Berlin 2002), but he adds to this liberal paradigm an emphasis on social communities (communitarianism) and a prioritization of civic virtues and the responsibilities of citoyens (republicanism). Both aspects are fundamentally necessary for an appropriate liberal conception. Contrary to traditional liberal thought and in line with discourse ethics, Ulrich does not accept the reduction of the individual to some “atomistic” existence that is just “set” in society or whose freedom is “endangered” by the state or by others. According to Ulrich, being a member of both a pluralistic society and the political arena are essential for every individual.

With that said, Ulrich also deploys these same republican and liberal elements against the tendencies of communitarianism to exaggerate community—individual citizen rights (including rights against the state) are still paramount and it remains everyone’s individual responsibility as citizens to participate in a shared res publica (Ulrich 2008a: 274ff.). The free and democratic society thus depends on the civic sense and political participation of its citizens: “Republican freedom is conceived as the politically constituted greatest possible equal freedom of all citizens. It includes, and is indeed a precondition for, their entitlement to active participation as citizens of the state (citoyens) in the democratic self-determination of a well-ordered life with others in a free society” (282). Thus, elements of all three lines of thought (liberalism, communitarianism, and republicanism) coalesce into a version of republican liberalism that upholds a conception of positive freedom (participatory self-determination of legitimate ends) that is in turn dependent on a sense of civic virtues (279).

While Ulrich’s reference to a formal (rational) ethics “leaves the settlement of all material questions to the public use of reason (Kant, Rawls) by mature and responsible citizens of the res publica” (Ulrich 2008a: 283), individuals must adhere to a minima moralia in order to uphold the regulative idea of a reasoning public. In short, citizens need to be willing 1) to reflect on their preferences and attitudes and be willing 2) to reach an agreement on impartial, fair principles and procedural rules in a deliberative process. Furthermore, they need the inclination 3) to compromise in areas of dissent and 4) to accept the need for the legitimation of their acts, practices, and institutions (299).

One final point is extremely important. For Ulrich, civic virtues are not only necessary conditions for dealing with political matters in the public sphere but within the economy too. Since in discourse ethics the deliberative process is what gives legitimacy to any action, civic virtues are also economic citizen virtues insofar as business activities always have public relevance for Ulrich:

p.211

[T]he idea of a neat and tidy separation between the political citizen (as homo politicus) and the economic citizen (as homo oeconomicus) turns out to be the symptomatic expression of a privatistically reduced self-understanding of the bourgeois who has lost his awareness of the priority and indivisibility of his status as a citoyen. The core of a republican economic ethics consists precisely in reflecting on the indispensable republican civic ethos in the self-understanding of the economic agents and putting it into practice. From this point of view, all economic agents essentially share a responsibility that cannot be delegated. Their shared responsibility refers to the quality of societal processes of deliberation, particularly in regard to debates concerned with the general economic, social and political conditions for the legitimate pursuit of private economic interests.

(Ulrich 2008a: 300)

It is this integrity of the individual that is the regulative idea of the individual dimension of Ulrich’s economic ethical approach. All citizens need to adhere to the principles of the deliberative process in all areas of their life, including the economic, whether as employees, managers, or consumers.

The meso level: normative stakeholder management

In the debate on business ethics it is now widely accepted that businesses face legitimate claims by actors other than shareholders. This paradigmatic change incorporates a shift from a shareholder value approach to a stakeholder one (Freeman 1984; Freeman and McVea 2001; Freeman 2004). The business of business is not merely business (see the opposite position by Friedman 1970). It is, rather, to strike a balance (itself not well-defined) between different claims of various stakeholder groups. But why should firms take stakeholder interests into account?

In management theory, a strategic response is dominant. On this strategic view, a firm should attend to (or respect) the interests of stakeholders because doing so tends to have a bottom line pay-off. Within the last two decades, a corporation is better off, even with its increased power,6 if it responds to the correlative and increased interest of “critical” components of society. For example, one might conceive of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) as the professionalized voices of some members of civil society. One of the NGOs’ main goals is the mobilization of the public (and consumers) to put pressure on (multinational) corporations in order to launch concrete business practices for greater social justice. A telling example of mobilization of consumer power through NGOs is the Brent Spar case of Royal Dutch Shell in 1995 (for details see the case studies of Paine 1999a, 1999b; and Beschorner 2005). Of course, from a strategic point of view, increasing societal pressure in favor of just business practices may entail economic costs for firms, with relatively higher costs imposed on smaller firms. Nonetheless, it is economically smart from the business perspective to deal with these societal demands and to incorporate relevant organizational measures within the firm. Consequently, elements of risk management to avoid “negative attention” by stakeholder groups have been integrated in traditional management systems. In this sense, the social responsibility of firms is a certain type of “smart management” to prevent harming the corporate image and to improve the firm’s reputation. In this way, the social responsibility of firms is related to the power and spheres of influence of certain stakeholders. Businesses take ethical issues into account if—and only if—they “pay.”

p.212

If we turn from the strategic to the normative consideration of stakeholders, then it could be argued that the negative external effects of business practices—social as well as ecological (world) problems—need to be ameliorated, if not solved. In instances of incomplete law or regulation, Ulrich argues that firms have the moral obligation to avoid negative external effects resulting from their practices. The author criticizes the strategic stakeholder approach due to its orientation on the stakeholders’ bargaining power. Basing stakeholder dialogues on power (the more powerful a stakeholder is, the more (s)he has to say) obviously leads to moral conundrums: Why should some stakeholders have a louder voice then others? Or, even, why should some stakeholders be excluded from a discourse while others are allowed to articulate their demands? Obviously, these are not legitimate practices from a discourse ethical point of view. One argument must count as one argument. In contrast to the power-based arguments in traditional strategic management Ulrich suggests a critical approach, as a form of regulative idea, that verifies “who ought to assert entitled stakes to the business (thus not merely: who can assert the stakes due to his or her power)” (our translation, Ulrich 1997: 443).

As we have stated above—regarding Habermas’ ideas—a discourse does not take into consideration all interests of all participants. Thus, a discourse is more than a mere dialogue in which (some) parties are engaged in a conversation; rather, it is an ideal dialogue in which normative criteria define the circumstances for a moral conversation. It is important to note that, in discourse, certain stakes or interests have the status of “candidates” who will then be justified according to the question whether or not it supports a greater good (beyond the mere self-interests of the participants). More precisely, Habermas and Ulrich suggest a twofold test of the specific stakes within discourses: first, the normative propositions that emerge must be deemed responsible in the sense that they are consensually justified as legitimate in a rational process of (power free) deliberation. All participants “re-spond” (dialogical) to the question of whether or not the norm can be seen as satisfied for all affected. Second, the renunciation of one’s own interests must be reasonable (Ulrich 2000: 13). It would be unreasonable if the norm would lead to the negligence of some actors or their interests. After all, the economic interests of a firm are not per se unreasonable. In fact, these interests are quite reasonable if the existence of the firm is at stake. Nonetheless, in a discourse ethical perspective, the firm’s interest must also always be regarded with respect to the first criteria, taking into account whether the interest is merely selfish (e.g., in favor of just one stakeholder, the shareholders) or whether it reflects a more general interest.

For discourse ethicists, two aspects are important here: First, the ideal dialogue does not lead to an absence of specific interests of the participants, but it makes these interests visible (Habermas 1993: 57–58). Second, as the term “candidates” signalizes, Habermas’ and Ulrich’s variant of discourse ethics is not absolutistic in the sense that one specific moral standard has to be applied. In fact, every normative proposal—even those that might seem absurd, such as more child labor or excluding males or females from a board of directors—can be discussed. Every proposition has the status of a candidate—a candidate for concrete moral practices. However, whether or not the proposition is legitimate depends on whether it is responsible and reasonable (as just noted). The dialogic perspective indicates, for example, that profit seeking is not per se an illegitimate practice, since the existence of firms depends on a certain margin of profit. Profit seeking might also be seen by the discourse participants as satisfactory to all those affected. However, it could be assumed, though without any certainty, that participants in a discourse (including workers for example) might not agree upon an idea of profit maximization if this entailed the exclusion of any consideration of the interests of stakeholders other than shareholders.

To conclude, first, Ulrich emphasizes in contrast to the strategic perspective the relevance of communicative action (deliberation versus bargaining). The German term for deliberation, “argumentative Verständigung,” includes both understanding and consensus. Second, Ulrich underlines the non-identity between real and ideal communication communities, between the “Is” and the “Ought” (Ulrich 1997: 80–82 and 448, 1999: 84) which allows him, third, to characterize the moral point of view as a “regulative idea” that aims at bridging practices of the real world with the normative orientations of the ideal. It is in this sense that Ulrich’s approach, as noted previously, is not a technique that is applied in certain situations but a more holistic orientation by which individuals may sift, consider, and legitimate the practices that engage and underlie their lives and societies.

p.213

The strengths of Ulrich’s strict ethical perspective can be seen as a more general critique that takes into account the ends of business activities as well as the means of business practices. Such a critique is relevant from a theoretical as well as practical point of view. From a theoretical perspective, Ulrich conceptualizes the embeddedness of firms in a broader societal context (and not merely within the economic system) and honors contributions of businesses toward a “good society.” Ulrich develops his idea from a pure “moral point of view” without accepting somewhat empirical circumstances that might prevent concrete moral practices. It is important for him to rethink what business ethics should be, and this leads to a diminished focus on practical solutions. Ulrich regards this “full play” of ethics as the specific strength of Integrative Economic Ethics. Others, however, regard the neglect of “real communication communities” as a particular weakness of Ulrich’s concept.

From a rather practical point of view, Peter Ulrich’s normative position questions core aspects of business practices. These practices include the ethical quality of products and services, the production processes (including workplace issues) and the sales process. In a practical sense, these normative claims may point to an ontological basis for corporate values as a fundamental aspect of business activities. Such corporate values may, for example, result in an explicitly formulated corporate philosophy and other institutional arrangements for just business practices. In sum, and in his own words, Peter Ulrich stands for a “critical stakeholder approach which emphasizes the difference to strategic management orientations and undertakes fundamental reflections for management sciences while it avoids categorical confusions and shortcomings” (our translation, Ulrich 1997: 448).

The macro level: republican liberalism and regulatory ethics

Any form of market economy needs some sort of justified political and social framework. The aim of Integrative Economic Ethics is to embed or situate the market within an overall ethical and political conception, legitimated by the moral point of view:

The justification of a certain order of the market economy consists in embedding the market in an overall conception, taking into account both the market and the non-market elements of well-coordinated socio-economic interactions in a society. The determination of such a conception, and in particular of the precise role which can be ascribed to the market as a partial coordination mechanism within it, is the task of institutional politics. The problem is obviously of a normative kind: as with every legitimate form of politics, regulatory politics must be oriented on justified normative principles. The clarification of the corresponding orientational problems is the task of regulatory ethics.

(Ulrich 2008a: 315)

Due to its strong social and political impetus and its discourse ethical foundation, Integrative Economic Ethics lays out a substantial critique of classic economic paradigms and discusses the problems of a neoliberal market order at great length (Ulrich 2008a, Chapter 8). Given the inherent political limits of liberal economics (with its presumption against political control over market processes) and taking into account the substantial empirical shortcomings of communism and socialist economies, Ulrich turns to concepts of a political order that are less dogmatic and more open to interpretation.

p.214

One such alternative approach is the paradigm of a “social market economy.” This economic order, which has accompanied German political thought for the past sixty years, strives to resolve the challenge of constituting and moderating a just market economy. The social market economy, as articulated by the ordoliberal school of economic thought (Lorch 2014), can be considered to be one of the more successful approaches of a “third way” (Giddens 1998) operating between the binary opposition of “capitalism vs. communism.” Ordoliberalism and its fruitful elaboration of a social market economy is thus the point of departure for an application of Integrative Economic Ethics to questions of market regulation. To understand this fit, a short introduction of ordoliberalism is necessary.

During and after World War II the “ordoliberals,” attempted to revitalize economic thinking in Germany (Röpke 1966; Rüstow 1950; Müller-Armack 1946). These thinkers laid the theoretical foundation for the unique economic success story of the post-war German economy—the “Wirtschaftswunder” (or the “economic wonder” see Sally 1996; Ptak 2004). (The major ordoliberal thinkers were also members of the renowned Mont Pelerin Society that reinvented and broadcast liberal political and economic thought—their efforts are today commonly known as neoliberalism (Plickert 2008; Mirowski and Plehwe 2009)). With their focus on a “third way” between laissez-faire capitalism and socialist planning, the ordoliberals considered how seemingly economic decisions—about government policies, business practices, and the ends of business—were, in fact, deeply related to the general order of society. With the German society and economy devastated after World War II, the ordoliberals realized that the government had to think about how to rebuild not only its economy but society as a whole. They consequently discussed and debated both historical ideal types of society and economy—the liberal unbound market economy as well as the planned socialist economy. With their analysis of the two historical forms they came to the conclusion that both ideologies contributed to the social crises of their time. Nonetheless, the “third way” of the ordoliberals remains closely related to traditional liberal thought. Setting off from the idea of individual freedom, the ordoliberals set out to “reinvent liberalism from the ground up” (our translation, Miksch 1949: 163).

The ordoliberal version of the social market economy became a framework for the post-war German economic and social order. Essential to this ideal was an awareness of the interconnectedness of the economy with all other spheres of society (i.e., politics, law, culture, etc.). The economy is not disconnected from society (as it was considered to be in laissez-faire liberalism) but an integral part of society, dependent on social and political forces it cannot (re-)produce on its own. For the social market economy, the terms “social” and “market economy” are not in a hierarchical order but are equals:

Even though the opinion has been voiced in Germany that all that is needed in order to resolve social problems is the fulfillment of economic principles, one should see clearer today that this instrumental view cannot live up to the task at hand. We are not only talking about shaping an economical order, rather we need to incorporate it into a holistic societal design.

(our translation, Müller-Armack 1952: 462)

p.215

Developing a theory of the social market economy as a socially “embedded economy,” the ordoliberals incorporated strong normative statements about how society in general was supposed to be structured in order to be able to embed a productive and competitive market order (see, for example, one of the few English publications by the ordoliberal thinkers, that of Müller-Armack 1978). Ordoliberals thus discussed different kinds of social norms, values, and individual virtues necessary for a competitive market order to be beneficial for all.

The ordoliberal line of thought turns out to be a natural fit to the political and social imperatives of Integrative Economic Ethics, with its emphasis on a republican order of equally free citizens and the moral significance of the interconnectedness of the economy with all other fields of society, not to mention the discursive perspective on social norms and values as a necessary underlying foundation of the social market economy. The ordoliberal perspective, in other words, matches Ulrich’s critiques of mainstream economics and of laissez-faire capitalism, and it expresses his search for an embedded market order.

In an attempt to modernize and refresh the thoughts of ordoliberals with regards to a social market economy, Integrative Economic Ethics therefore discusses ways to connect this more historical approach to society and economy and enriches it with its own idea of republican liberalism. Although the general impetus of the social market economy, to connect economic thought with ethical considerations of society and morals in general, remains useful, the normative foundations and the specific solutions discussed by ordoliberals may seem outdated and not helpful by today’s philosophical, social, and political standards. Specific ordoliberal normative thoughts (e.g., that the political order be imbued with values of Christian religion, of chivalry, and of rural life) may seem peculiar by today’s more pluralistic standards (see Lorch 2014 for a critical discussion of the normative assumptions of ordoliberalism). Yet Ulrich’s approach transcends the historical attempt of the ordoliberal school by adding a republican liberalism as the philosophical and normative foundation for a modern social market economy. In Ulrich’s version the processes of deliberation, not material norms, take priority: the values of the political order cannot be determined before any of these processes have taken place.

Concluding remarks

Following Ulrich’s critical discussion of ordoliberal thought and his attempt to strengthen the social and political aspects of economic policy, there are various recent attempts to discuss this important line of ordoliberal economic thought and integrate it into the larger body of ideas that is Integrative Economic Ethics (Thielemann 2010; Lorch 2014). More generally, the approach of Integrative Economics Ethics has had a tremendous and lasting impact on German debates of economic and business ethics. However, Ulrich’s approach has received little international attention. This is a shame, considering its unique and important contributions to a holistic philosophical approach to business ethics.

One reason for the lack of visibility and exposure of Integrative Economic Ethics arises from issues of translatability. Ulrich’s theory is firmly set in German philosophical debates situated within a tradition that is typically indebted to either Kant or critical theorists (chiefly Habermas). It is difficult not only to explain adequately what “economic ethics” really is, but also to translate the extensively used German terms such as Lebenswelt that do not have a direct equivalent in the English language.

Ulrich’s approach has, on the other hand, influenced important international scholars of business ethics such as Florian Wettstein (2009), a former student of Ulrich, working on questions of business and human rights, as well as Scherer and Palazzo (2007), most prominently working on concepts of political CSR. In a sense, the notion of political CSR is well established in Integrative Economic Ethics and can be directly traced to the thorough political-philosophical works of Ulrich.

p.216

Nonetheless, Integrative Economic Ethics has also received its fair share of criticisms due to its firm and resolute philosophical interpretation of discourse ethics as the basic condition for legitimate action and its insistent critique of economic rationality. Ulrich demands, à la Kant, a very self-conscious, autonomous economic actor, yet he gives little advice on how to deal with the inevitable conflicts between ethics and economic rationality, leaving many readers unsatisfied with the practical implications of his approach. As true of discourse ethics, the condition of ideal communication communities has been accused of overburdening the individual, resulting in endless “practical discourses” that leave the individual economic actor incapable of acting (e.g., Nutzinger 1994; Nutzinger 1996; Osterloh 1996; König 1999). This line of criticism, however, has to be regarded with some ambivalence: on the one hand, we agree with Ulrich on the importance of stressing the moral point of view as a regulative idea since making any compromises, such as confusing the moral point of view with empirical facts, “given” conditions, and so on, would indeed lead to a halt in ethical reflection and thus to “ethical suicide” (Kersting 1993). On the other hand, we agree with Ulrich’s critics that he is not assertive enough in dealing with actual cases and practices. Ulrich’s theory thus needs to respond more fully to the criticism that it might be somewhat out of touch with everyday business situations. For practitioners, it can be unclear how the theoretically appealing idea of ideal speech situations of discourse ethics can be translated to specific business situations or conflicts. Ulrich’s approach may sound entirely reasonable, a model for what everyone wants, at least in theory, yet it does not entail any direct consequences for business practices.

In two lesser-known articles, Peter Ulrich (2004a, 2004b) proposes what he calls “grass root reflections,” which attempts to connect the concept of the ideal communication community with concrete moral orientations of “flesh and blood” agents. Actions, Ulrich states, are de facto always grounded on the moral orientations of the actors. This idea, and the possible extension of Integrative Economic Ethics toward a normative theory of practices, has recently sparked new discussions (Beschorner et al. 2015). But, considering the breadth and depth of Integrative Economic Ethics, there still appears to be lots of room for further advancements, discussions, and applications of this important approach to business ethics.

Essential readings

The essential theoretical foundation of Integrative Economic Ethics can be found in Peter Ulrich: Integrative Economic Ethics: Foundations of a Civilized Market Economy (2008a), also available in German (Ulrich 2008b) and Spanish (Ulrich 2008c). For a thorough review of Ulrich’s theory see Jeffery Smith’s book review of the same (2013). The philosophical basis of Integrative Economic Ethics is found in Jürgen Habermas, Theory of Communicative Action (1981, 2 vols). We also recommend Habermas’ (short) book Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics (1993) for an introduction to discourse ethics. For a brief introduction to the general idea of a social market economy, we recommend Alfred Müller-Armack’s article, “The Social Market Economy as an Economic and Social Order” from 1978. Wilhelm Röpke’s book A Humane Economy: The Social Framework of the Free Market (1960) is a great introduction to ordoliberal thought.

For further reading in this volume on motivation and rationality and their roles in economic theory, see Chapter 17, The contribution of economics to business ethics. On the idea that firms and agents are embedded in social relations, see Chapter 8, Feminist ethics and business ethics: redefining landscapes of learning through practice. On the very idea of enlightenment and disinterested rationality, see Chapter 3, Theory and method in business ethics. For an account of business as embedded within the culture of central European nations both before and after communism, see Chapter 39, Business ethics in transition: communism to commerce in Central Europe and Russia. For a discussion of how entrepreneurship is a moral notion, see Chapter 16, The ethics of entrepreneurship. For a discussion of how stakeholder thinking may prove an obstacle to a comprehensive ethical perspective, see Chapter 11, Stakeholder thinking. On a political interpretation of social responsibility, see Chapter 10, Social responsibility.

p.217

Notes

1 For a very helpful introduction to the work and life of Jürgen Habermas see Baert (2001).

2 We do not discuss Apel’s position here. In contrast to Habermas, Apel suggests developing a universal moral point of view based on cultural invariances (cf. Apel 1980). This research strategy tends to lead to fundamentalism and seems—at least for business ethics issues—not adequate. Habermas’ approach is in this sense more moderate since, as we will see, he attempts to reconstruct his version of Discourse Ethics in relation to lifeworlds (in plural!). See Scherer (2005).

3 We refer to the German original first published in 1991. Quotes and specific Habermasian terms are taken from the English translation by Ciaran Cronin, published in 1993 by MIT Press.

4 There are unfortunately very few publications by Ulrich in English; see for example Ulrich 1998; 2002; 2008a; 2009.

5 The concept of a moral point of view that is understood in a rational ethical sense can be found in Baier (1958).

6 In the 1980s the number of transnational corporations has tripled from 10,000 to 30,000 (Arrighi 1999). In 2001, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in its World Development Report counted 62,000 transnational corporations and 820,000 foreign affiliates. Merger and acquisition activities of businesses and increasing profits have also led to an increasing (financial) power of firms. For example, the revenue of Exxon Mobil in 2002 (205 billion dollars), the world’s largest corporation, is higher than the GDP of countries such as Denmark (172), Indonesia (173), Turkey (184), or Saudi Arabia (188) in the same year (numbers by IMF).

References

Apel, K.-O. (1980). Towards a Transformation of Philosophy. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Arrighi, G. (1999). “Globalization and Historical Macrosociology,” in J.L. Abu-Lughod (ed.), Sociology for the Twenty-first Century, Continuities and Cutting Edges. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 117–133.

Baert, P. (2001). “Jürgen Habermas,” in A. Elliott and B.S. Turner (eds), Profiles in Contemporary Social Theory. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; New Delhi: Sage, 84–93.

Baier, K. (1958). The Moral Point of View: A Rational Basis of Ethics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Berlin, I. (2002). Liberty: Incorporating Four Essays on Liberty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beschorner, T. (2005). “Social Responsibility of Firms,” in J. Beckert and M. Zafirovski, (eds), International Encyclopedia of Economic Sociology. London: Routledge, 618–622.

Beschorner, T. (2006). “Ethical Theory and Business Practices: The Case of Discourse Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 66:1, 127–139.

Beschorner, T., P. Ulrich, and F. Wettstein (eds) (2015). St. Galler Wirtschaftsethik. Programmatik, Positionen, Perspektiven. Marburg: Metropolis.

Enquête-Kommission Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft (2002). “Schlussbericht. Globalisierung der Weltwirtschaft—Herausforderungen und Antworten.” Berlin: Deutscher Bundestag.

Forst, R. (2002). Contexts of Justice: Political Philosophy Beyond Liberalism and Communitarianism. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Marshfield, MO: Pitman.

Freeman, R.E. (2004). “The Stakeholder Approach Revisited,” Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Unterneh mensethik 5:3, 228–241.

Freeman, R.E. and J. McVea (2001). “A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management,” in M.A. Hitt, R. E. Freeman and J.S. Harrison (eds), The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management. Oxford: Blackwell Business, 189–207.

p.218

Friedman, M. (1970). “The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase its Profits,” The New York Times Magazine, September 13, 32–33, 122–126.

Giddens, A. (1998). The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity.

Gilbert, D.U. and M. Behnam (2009). “Advancing Integrative Social Contracts Theory: A Habermasian Perspective,” Journal Of Business Ethics 89:2, 215–234.

Gilbert, D.U. and A. Rasche (2007). “Discourse Ethics and Social Accountability: The Ethics of SA 8000,” Business Ethics Quarterly 17:2, 187–216.

Habermas, J. (1981). Theory of Communicative Action, Vol. 1: Reason and the Rationalization of Society, T A. McCarthy (trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1981). Theory of Communicative Action Vol. 2: Lifeworld and System: A Critique of Functionalist Reason, T. A. McCarthy (trans.). Boston: Beacon Press.

Habermas, J. (1991/1992). Erläuterungen zur Diskursethik. Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Habermas, J. (1993). Justification and Application: Remarks on Discourse Ethics. C. P. Cronin (trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Honneth, A. (ed.) (1993). Kommunitarismus: eine Debatte über die moralischen Grundlagen moderner Gesellschaften. Frankfurt a.M.: Campus.

Kant, I. (1786). “What Does it Mean to Orient Oneself in Thinking?” in A. Wood and G. di Giovanni (eds), Religion and Rational Theology, The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–18.

Kersting, W. (1993). “Moralphilosophie, angewandte Ethik und Ökonomismus,” Zeitschrift für Politik 43:2, 183–194.

König, M. (1999). “Ebenen der Unternehmensethik,” in H.G. Nutzinger, Hans and Berliner Forum zur Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik (eds), Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik: Kritik einer neuen Generation. Zwischen Grundlagenreflexion und ökonomischer Indienstnahme. München: Hampp, 55–73.

Lorch, A. (2014). Freiheit für alle. Grundlagen einer neuen Sozialen Marktwirtschaft. Frankfurt/ New York, NY: Campus.

Miksch, L. (1949 [2008]). “Versuch eines liberalen Programms,” in N. Goldschmidt and M. Wohlgemuth (eds), Grundtexte zur Freiburger Tradition der Ordnungsökonomik. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 163–170.

Mingers, J. and G. Walsham (2010). “Toward Ethical Information Systems: The Contribution of Discourse Ethics,” MIS Quarterly 34:4, 833–854.

Mirowski, P. and D. Plehwe (eds) (2009). The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Müller-Armack, A. (1946). Wirtschaftslenkung und Marktwirtschaft. Hamburg: Kastell.

Müller-Armack, A. (1952 [2008]). “Stil und Ordnung der Sozialen Marktwirtschaft,” in N. Goldschmidt and M. Wohlgemuth (eds), Grundtexte zur Freiburger Tradition der Ordnungsökonomik. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 457–466.

Müller-Armack, A. (1978). “The Social Market Economy as an Economic and Social Order,” Review of Social Economy 36:3, 325–331.

Nutzinger, H.G. (1994). “Unternehmensethik zwischen ökonomischem Imperialismus und diskursiver Überforderung,” in Forum für Philosophie (ed.), Markt und Moral. Die Diskussion um die Unternehmensethik. Bern, Stuttgart, Wien: Haupt, 181–214.

Nutzinger, H.G. (1996). “Zum Verhältnis von Ökonomie und Ethik. Versuch einer vorläufigen Klärung,” in H.G. Nutzinger (ed.), Naturschutz—Ethik—Ökonomie. Marburg: Metropolis, 171–196.

Osterloh, M. (1996). “Vom Nirwana-Ansatz zum überlappenden Konsens. Konzepte der Unternehmensethik im Vergleich,” in H.G. Nutzinger (ed.), Wirtschaftsethische Perspektiven III. Unternehmensethik, Verteilungsprobleme, methodische Ansätze. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 203–229.

Paine, L.S. (1999a). “Royal Dutch/Shell in Transition (A),” Harvard Business Online, Case 300–039.

Paine, L.S. (1999b). “Royal Dutch/Shell in Transition (B),” Harvard Business Online, Case 300–040.

Pettit, P. (1997). Republicanism: A Theory of Freedom and Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Plickert, P. (2008). Wandlungen des Neoliberalismus. Eine Studie zu Entwicklung und Ausstrahlung der “Mont Pèlerin Society.” Stuttgart: Lucius & Lucius.

Ptak, R. (2004). Vom Ordoliberalismus zur Sozialen Marktwirtschaft. Stationen des Neoliberalismus in Deutschland. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Rawls, J. (1999 [1971]). A Theory of Justice, revised edition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Reed, D. (1999a). “Stakeholder Management Theory: A Critical Theory Perspective,” Business Ethics Quarterly 9:3, 453–483.

Reed, D. (1999b): “Three Realms of Corporate Responsibility: Distinguishing Legitimacy, Morality and Ethics,” Journal of Business Ethics 21, 23–35.

p.219

Röpke, W. (1960). A Humane Economy: The Social Framework of the Free Market. Chicago, IL: H. Regnery Co.

Röpke, W. (1966). Jenseits von Angebot und Nachfrage, 4th edition. Erlenbach-Zürich: Rentsch.

Rüstow, A. (1950). Das Versagen des Wirtschaftsliberalismus, 3., rev. edition F.P. und G. Maier-Rigaud (trans. and eds) (2001). Marburg: Metropolis.

Sally, R. (1996). “Ordoliberalism and the Social Market: Classical Political Economy from Germany,” New Political Economy 1:2, 1–18.

Scherer, A.G. (2005). “Neuere Entwicklungen der Diskursethik und deren Beitrag zur Lösung des philosophischen Grundlagenstreits zwischen Universalismus und Relativismus in der interkulturellen Ethik,” in: T. Beschorner, B. Hollstein, M. König, M.-Y. Lee-Peukerand, O. Schumann (eds), Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik. Rückblick—Ausblick—Perspektiven. München: Hampp, 213–231.

Scherer, A. and Palazzo, G. (2007). “Towards a Political Conception of Corporate Responsibility: Business and Society Seen from a Habermasian Perspective,” Academy of Management Review 32:4, 1096–1120.

Smith, J. (2013). “Book Review: Integrative Economic Ethics: Foundations of a Civilized Market Economy by Peter Ulrich,” Business Ethics Quarterly 23:1, 151–154.

Thielemann, U. (2010). Wettbewerb als Gerechtigkeitskonzept: Kritik des Neoliberalismus. Marburg: Metropolis.

Ulrich, P. (1977). Die Grossunternehmung als quasi-öffentliche Institution: eine politische Theorie der Unternehmung. Stuttgart: Schäffer-Poeschel.

Ulrich, P. (1993). Transformation der ökonomischen Vernunft: Fortschrittsperspektiven der modernen Industriege sellschaft, 3rd revised edition. Bern: Haupt.

Ulrich, P. (1994). “Integrative Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik - ein Rahmenkonzept,” in Forum für Philosophie (ed.), Markt und Moral. Die Diskussion um die Unternehmensethik. Bern: Haupt, 75–107.

Ulrich, P. (1996). “Unternehmensethik und ‘Gewinnprinzip,’” in H.G. Nutzinger (ed.), Wirtschaftsethische Perspektiven III—Unternehmensethik, Verteilungsprobleme, methodische Ansätze. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 137–171.

Ulrich, P. (1997). Integrative Wirtschaftsethik. Grundlagen einer lebensdienlichen Ökonomie. Bern: Haupt.

Ulrich, P. (1998). “Integrative Economic Ethics—Toward a Conception of Socio-Economic Rationality,” Working paper of the Institut für Wirtschaftsethik, University of St Gallen, No. 82, St Gallen.

Ulrich, P. (1999). “Zum Praxisbezug der Unternehmensethik,” in G.R. Wagner (ed.), Unternehmensführung, Ethik und Umwelt. Wiesbaden: Gabler, 74–94.

Ulrich, P. (2000). “Integrative Wirtschaftsethik: Grundlagenreflexion der ökonomischen Vernunft,” Ethik und Sozialwissenschaft 11:4, 555–566.

Ulrich, P. (2002). “Ethics and Economics,” in L. Zsolnai (ed.), Ethics in the Economy. Handbook of Business Ethics. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, 9–37.

Ulrich, P. (2004a). “Prinzipienkaskaden oder Graswurzelreflexion?—Zum Praxisbezug der Integrativen Wirtschaftsethik,” in P. Ulrich, P. and M. Breuer (eds), Wirtschaftsethik im philosophischen Diskurs. Begründung und ‘Anwendung’ praktischen Orientierungswissens. Würzburg: Königshausen und Neumann, 127–142.

Ulrich, P. (2004b). “Wirtschaftsethische Graswurzelreflexion statt angewandte Diskursethik: Persönliche Sicht einiger Differenzen zwischen St. Galler und Berliner Position,” in T. Bausch (eds), Wirtschaft und Ethik: Strategien contra Moral? Münster: LIT-Verlag, 21–41.

Ulrich, P. (2008a). Integrative Economic Ethics: Foundations of a Civilized Market Economy, James Fearns (trans.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Ulrich, P. (2008b). Integrative Wirtschaftsethik: Grundlagen einer lebensdienlichen Ökonomie. Bern: Haupt.

Ulrich, P. (2008c). Ética Económica Integrativa: Fundamentos de una economía al servicio de la vida. L. A. Panchi Vasco (trans.). Quito, Ecuador: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

Ulrich, P. (2009). Civilizing the Market Economy: The Approach of Integrative Economic Ethics to Sustainable Development. Discussion Papers of the Institute for Business Ethics/Berichte des Instituts für Wirtschaftsethik, Nr. 114. St Gallen.

Ulrich, P. and Breuer, M. (eds) (2004). Wirtschaftsethik im philosophischen Diskurs—Begründung und “Anwendung” praktischen Orientierungswissens. Würzburg: Königshausen + Neumann.

Wettstein, F. (2009). Multinational Corporations and Global Justice: Human Rights Obligations of a Quasi-Governmental Institution. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.