p.239

Gordon G. Sollars

The term “corporation” has been used to designate any group of persons united for some purpose. Within the business ethics literature the term is sometimes used synonymously with the terms “company” or “firm” simply to denote an organization with a business purpose, with some authors explicitly highlighting ethical issues of such organizations without regard to their legal form (Hartman 1996). The modern business corporation1, however, is a legally recognized organization with a class of investors (shareholders) who typically elect a committee (board of directors) that provides the highest level of management oversight for the activities related to the corporation. Investors’ shares may be publically bought and sold, or “closely held” by members of the corporation (Klein et al. 2006). The corporation has become the dominant form of business organization (Hansmann 1996).

These features of the corporation make salient questions of identity and agency. Ethical issues concerning responsibility arise from the difference between collective and individual action. Is the corporation best thought of as a sort of single entity or as some aggregate of persons? If an entity, is the corporation a moral agent somehow separate from the persons who act on its behalf? To what degree may shareholders be held liable for actions presumed to be taken either by the corporation or by its directors or employees? This chapter will briefly outline the historical antecedents of the modern business corporation, analyze its identity as understood by current theories, and explore the sense in which a corporation engages in moral action.

Historically, the general description of the corporation is that of an association of persons, treated in some legal respects as a single person. Members of a corporation were individuals united for some common purpose, be it religious, governmental, or commercial. This section begins with the early origins of the corporation as a device to deal with the interaction between a common purpose and property law, and continues through the addition to the corporation of the modern features of joint-stock ownership, shareholder limited liability, and general incorporation, each feature to be defined below.

Arguably, the need for something like the corporation arose from the first combining of associations with property ownership (Seymour 1903). Property held in common by an aggregate of individuals would, over time, tend to pass to heirs who might not hold the aims or purposes that motivated those in the original aggregate. Ultimately, ownership of the property by any individuals still sharing the original purpose would be lost. This concern was addressed by the understanding that it was the association itself, in some sense, that owned the property, rather than individual members of the association having common ownership.

p.240

The need for this understanding arises from the rules specific to common property, in both Roman civil and English common law, according to which each owner has an undivided inheritable interest in the common property. Another form of property, joint property or “property by the entireties,” would have addressed the problem of dispersed ownership across persons without a shared purpose, but at the expense of creating a different problem. With joint property, an owner’s property interest at death is absorbed into that of the remaining owners, so that a group of owners would retain control as members died. However, the rules for joint property traditionally required that all the owners take title at the same time; the attempt to include new persons as property owners would thereby transform the ownership from joint to common. Other forms of property besides common and joint are, of course, imaginable. Within the existing property framework of both Roman and English law, however, treating an association as an entity capable of property ownership in its own right was apparently less of a conceptual obstacle than the development of an additional form of property.

The English law borrowed heavily from Roman law with regard to the corporation (Seymour 1903). In Roman law, the idea of the corporation as an association of persons with a continuing existence not identical to its current members was applied in a wide variety of contexts: municipalities, religious societies, and groups of artisans. This same wide application was repeated centuries later in England (Seymour 1903; Williston 1888a).

Within England, the concept of the corporation was first applied to religious organizations (Seymour 1903). By the reign of King Henry IV (1399–1413), the idea was applied to municipal associations, perhaps driven by the governance requirements stemming from the increasing populations of cities and towns (Seymour 1903). In addition to owning property, corporations could make ordinances or by-laws (Anonymous 1702; Williston 1888a). By 1466 the corporate concept was being applied to trade guilds (Seymour 1903).

The continuing application of the same term to cover a variety of kinds of associations suggests that the distinction between “business” and “political” associations was not sharp. One of the first treatises on the corporation stated that the “general intent and end of all civil incorporations is for better government; either general or special.” By “special government,” the author referred to the “managers of particular things” such as trade guilds (Anonymous 1702). The label of “government” was appropriate because, e.g., guilds had the power to regulate the conduct not only of members but also of any person engaged in the trade in question. As corporations for commerce began being formed, they were created by a charter from the king or by Parliament that typically granted a monopoly over trade in a geographic area (Williston 1888a).

An alternative to the corporation was the common law partnership. The need for a charter from the king or Parliament made forming a corporation time-consuming and expensive; the partnership was formed by contract. The easy availability of the partnership form, however, was counterbalanced by other factors brought into focus because the partnership was not viewed as an entity but an aggregate of persons linked by contract. A partnership was dissolvable by any one of the partners, or by a partner’s death, and each partner’s actions bound the partnership as a whole. The issues raised by these factors were manageable when partnerships were small, but as commerce expanded, especially with regard to foreign trade, the need for capital grew beyond what a small number of persons could provide.

p.241

These new requirements for capital were met by the issue of “joint stock”2 that could be purchased by investors, thereby combining the capital from potentially a large number of persons. Initially, the issue, or “subscription,” of joint stock was for the life of a single project, with a pro rata division of profits at the end. The Royal African Company, trading by around 1660, hired its ships for each voyage, and was an instance of this initial practice. Later, the joint stock was subscribed for a term of years, as with the Russian Company, which owned ships used over several voyages, with old stock being sold to new buyers at the end of the term (Walker 1931; Williston 1888a). The use of joint stock was a method of financing not tied to the corporate legal form of organization, but also available to partnerships (Walker 1931).

One such joint-stock company, the South Sea Company, was a corporation chartered by Parliament in 1711, and it combined a trading monopoly over South America with a debt-for-equity swap of short-term government debt for shares of the company (Dale 2004). The value of the company’s shares first rose spectacularly and then fell disastrously in 1720, which led to the appellation “bubble” being applied, first to the event and then to joint stock companies more generally (“bubble companies”). With the so-called “Bubble Act” of 1720, Parliament prohibited the use of joint stock by unincorporated companies3 and adopted a policy of limiting access to incorporation (Harris 1994). As a result, few corporations were chartered during the eighteenth century, except for the building of canals (Handlin and Handlin 1945).

The policy appears to have had more effect than the legal prohibition. Although the Bubble Act specified harsh penalties for violations, there is a record of only one criminal prosecution under the Act during the eighteenth century (Harris 1994). With corporate status difficult to obtain, unincorporated companies raised the needed amounts of capital by issuing stock. Indeed, the term “joint-stock company” typically referred to an unincorporated company (Shannon 1954). These companies, strictly speaking illegal, were nevertheless applying to Parliament for the right to sue and be sued in the name of a company officer before the Bubble Act was repealed in 1825 (Shannon 1954), suggesting that these companies were widely tolerated due to their economic advantages. By 1825, when the Bubble Act was repealed, the total investment in unincorporated joint-stock companies has been estimated at between “£160 million and £200 million” (Shannon 1954).

Because partnership law was applied to the unincorporated joint-stock company, the substantial investment in these companies presents something of a challenge to the idea that limited liability is essential for obtaining investment by large numbers of persons who will have no active participation. By 1808 at least one company had 8,000 shareholders, and by mid-century there were about 1,000 joint-stock companies. On the other hand, the legal exposure of shareholders may have had little practical consequence given the procedural difficulties in bringing suit against large partnerships present in English law at that time, as each partner had to be named explicitly (Blumberg 1986).

Limited liability and general incorporation

Under limited liability a shareholder’s financial liability for debts of the corporation is capped at the value of the shareholder’s investment; assessments against the corporation can reach only those assets in the corporate name, not others held by the shareholder. The most common alternative, unlimited liability, applies to partnerships, in which debts of the partnership may fall on a partner individually and without limitation to the amount of his investment in the partnership. The availability of limited liability for members for debts of the corporation was not uniform. The English legal authorities Edward Coke and William Blackstone did not mention limited liability as a necessary element of the corporation (Blumberg 1986), nor is it listed as such by early treatises (Anonymous 1702; Kyd 1793) on the corporation. Some corporate charters expressly stated that their members were liable, while other charters expressly stated that members were not (Blumberg 1986). Authorities differ over what default rule for member liability applied. H.A. Shannon (1954), as noted previously, holds that the default was limited liability; Samuel Williston (1888b) argues that members of a company could be held liable for debts of a corporation, at least in courts of equity, if not courts of law. Interestingly, shareholders of railway companies, as a category, were granted limited liability from the beginning of the industry, perhaps because of the relatively large amounts of capital required, but also because of the recognized “public usefulness” of the railroads (Shannon 1954).

p.242

Attitudes began to change quickly, however, in the middle of the nineteenth century, perhaps because of the growing number of small capitalists. Between 1855 and 1857, Parliament passed the first legislation that allowed for general incorporation by simply registering a “memorandum of association” that stated the purpose of the corporation and whether liability was to be limited. Almost at once, incorporation with the certainty of limited liability was made easy to obtain (Shannon 1954).

Incorporation and limited liability in the United States

Incorporation was much more common in the US than in England. In the 20 years after the Revolutionary War, some 350 companies were incorporated in various states. Prior to 1809, corporate charters were routinely granted to companies involved in building canals, turnpikes, toll-bridges, and water supplies, as well as in banking and insurance, activities that required relatively large aggregations of capital, unlike manufacturing which at that time did not (Blumberg 1986; Dodd 1948). Some charters explicitly mentioned limited liability, but others were silent on the point. The default rule remains unclear, although there is evidence that shareholder liability for corporate debts depended on whether the charter granted the corporation the power to make assessments for additional capital against the members (Dodd 1948; Handlin and Handlin 1945).

A detailed understanding of the development of the corporation in the US during the nineteenth century is made difficult by several factors. First, incorporation was a matter of state law, and the various legislatures made changes to their laws of incorporation at different times (Dodd 1948). Second, at that time, shareholders did not initially pay the entire par value for their shares, instead being assessed for the remaining amounts over time; however, assessments could also be made by the corporation for amounts in excess of the par value (Blumberg 1986). Third, in addition to the two extremes of liability, limited and unlimited liability, there were regimes of double, triple, and proportional liability (Blumberg 1986; Dodd 1948).

The existence of proportional liability, by which a shareholder is liable only for that percentage of shares held in relation to the total shares outstanding, is particularly notable given later theoretical interest in this regime (Hansmann and Kraakman 1991; Sollars 2001). Proportional liability occurred in various state and business contexts during the nineteenth century, and was the law for all companies chartered or doing business in California until the early 1930s. The early enforcement procedure of shareholder liability allowed any creditor to sue any shareholder for the full claim, which encouraged the targeting of the wealthiest shareholders and proved unworkable. Over time, however, courts of equity developed the “creditors’ bill” procedure, invoked on behalf of all of a corporation’s creditors, where proportional liability was applied (Blumberg 1986).

The difference in timing among the states in the movement from unlimited, multiple, or proportional towards limited liability potentially constitute a “natural experiment” regarding the effect of limited liability. Although there are no detailed statistical studies for the 19th century directly on this point, general comparisons suggest that a state’s economic activity was not strongly affected by the liability regime selected (Blumberg 1986). Both E. Merrick Dodd (1948) and Phillip Blumberg (1986) suggest, however, that the lack of effect was a product of the overall lower levels of investment in the nineteenth century relative to the twentieth.

p.243

Some states had some kind of general incorporation laws rather than the requirement for special charters as early as 1800 (Handlin and Handlin 1945). A majority of the states did not have general incorporation, however, until after the Civil War, and some industries such as railroads were not included. By 1875, however, almost no state required special charters (Hamill 1999). Incorporation came to be viewed throughout the US as merely legal formality rather than a constituting event. The availability of general incorporation has, especially in the latter decades of the twentieth century, promoted the idea that the function of corporate law is to simply acknowledge the identity of a voluntary association, rather than to bring into existence by special legislative action an entity existing only at the pleasure of the state. The nature of corporate identity is considered next.

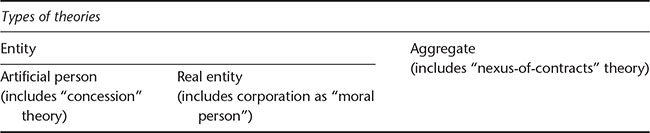

Theories of the corporation begin with a question of the nature of corporate identity: is the corporation an entity distinct in some sense from its components, or is the corporation an aggregate resolvable without residue into those components. As indicated in Table 14.1, below, entity theories may be further divided into those that view the corporation as an “artificial person,” or those that take the corporation to be a “natural” or “real” entity of some kind. Aggregate theory looks through the corporation to its shareholders or, in the modern version, to all those individuals or groups that conduct transactions with the corporation.

As noted in the previous section, the artificial person theory appears in the earliest writings on the corporation. Edward Coke refers to the corporation as existing “only in intendment and consideration of the law” (Williston 1888a), and older treatises state that the corporation is “framed by a policy or fiction of law” (Anonymous 1702, capitalization updated), or is “vested, by a policy of the law, with the capacity of acting, in several respects, as an individual” (Kyd 1793, spelling updated). As such, a corporation can be given the legal right to own property in the same manner as a natural person. In addition to retaining control of property, the artificial person can sue or be sued using a single name, rather than the names of all the members, as would be required with a partnership. During the period that the Bubble Act was legally in force (1720–1825), joint-stock companies could not be incorporated, and such companies often asked Parliament for the right to sue and be sued in the name of a single company officer. Furthermore, the life of the artificial person can be made indefinite in length, and thus independent of the lives of any of the members, allowing for greater continuity than the partnership.

Table 14.1 Types of theories (of the corporation).

p.244

In the US, Chief Justice Marshall advanced the artificial person theory with his classic statement that, “A corporation is an artificial being . . . existing only in contemplation of law,” which has “only those properties which the charter of its creation confers upon it, either expressly, or as incidental to its very existence.”4 As noted previously, until the 1850s, in both the US and England, legal incorporation required in most situations a case-by-case action by the state. Further, incorporation up until about that time often included some grant of legal monopoly, and, before general incorporation statutes became the norm, corporate charters might list specific privileges and restrictions. Putative actions of a corporation that were inconsistent with the charter were deemed ultra vires5 (“beyond the powers”) and thus not legally actions of the corporation.

Against this background, within the artificial-person conception the term “concession theory” is often used to highlight that special privileges not available by contract are being granted by the state. The concession variant of the artificial-person theory explains how an association can be imbued with properties that partnerships, formed by contract, do not have. For example, while partners face unlimited liability for the debts of a partnership, the state may concede limited liability to corporate shareholders. The question of whether limited liability could be available by contract is considered below.

At the same time, Marshall’s legal opinion may be read as giving support to a theory of the corporation as an aggregate rather than an entity. Marshall describes the corporate charter of Dartmouth College as “plainly a contract” among the parties, one specifying how property is to be used.6 As general incorporation statutes widely displaced specific legislative acts of chartering during the nineteenth century, the artificial person theory, especially in its concession form, lost relevance. Thus, in 1882 Justice Field stated, “Private corporations are, it is true, artificial persons, but . . . the courts will always look beyond the name of the artificial being to the individuals whom it represents.”7 The aggregate theory limited the power of the state to regulate a corporation, since such regulation fell upon the property rights of the contracting parties. Further, as incorporation became more available and charters less specific, the idea of the charter as a contract made possible a closer analogy between the corporation and the partnership, which had always been viewed as an aggregate of individuals.

Although the aggregate theory would return to have a vigorous life in the later decades of the twentieth century, the nineteenth-century version was supplanted by the entity theory. Morton J. Horwitz (1992) argues that, for various legal and economic factors, the analogy made by the aggregate theory between the corporation and the partnership began to break down in the late 19th and early twentieth centuries. In particular, Horwitz stresses the difference in liability between the partnership and the corporation after the middle of the nineteenth century, pointing to Chief Justice Taney’s concern, expressed as early as 1839, over the (lack of) analogy. Limited liability seemed to some as logically connected to the idea of the corporation as an entity (Horwitz 1992). If general incorporation—the formation of a corporation without an explicit act of a legislature—made the concession theory implausible, perhaps the corporation was a real entity.

The idea of corporation as a real entity was the dominant conception in France and Germany in the nineteenth century, and was brought to the attention of theorists in England and the United States by Frederick Maitland’s translation of a portion of a multivolume German text (Gierke 1913), which included an influential introduction by Maitland. The real-entity theory views the corporation not as a creation of the law, but rather as having an existence that may be recognized by law. The basis for the existence varies with the details of the particular theory. Arthur Machen (1911) argues that the corporation must have a separate existence from its components in order to explain its continuity over time. Harold Laski (1916) simply argues that “we are compelled” to treat the corporation as an entity, as reflected in language and legal decisions. In Otto von Gierke’s view the corporation is a “living organism” (Gierke 1913: xxvi). Of particular interest in the context of agency discussed below are real-entity theories grounded in the possibility that the corporation is a moral person (French 1979; Maitland 1905; Phillips 1992).

p.245

Real-entity theory grew in influence during the first several decades of the twentieth century. John Dewey (1926) began an attack on the real-entity theory, however, arguing that the law need be concerned only with the consequences of attaching various aspects of personhood to the corporation, rather than with the logical implications stemming from the “nature” of an entity. This focus on consequences rather than on the articulation of a theory of corporate personality proved highly influential, undercutting most theorizing over corporate identity until the 1980s (Bratton 1989; Phillips 1994),8 when interest in the aggregate theory returned through the influence of economics on the law (Coase 1960; Posner 1973).

Building upon the insights of Ronald Coase (1937), Armen Alchian and Harold Demsetz (1972) constructed a “team production” theory of the firm. In team production, inputs to the production process by team members create a joint product that is not easily separable into the contribution of each. Because individual contribution is hard to measure, each team member has an incentive to shirk, leaving the work to the others. This difficulty can be overcome if there is a party to monitor the production, and that monitor has the proper incentive if it can claim the residual amount of the joint product after all other input costs are paid. Because the monitor is the “one party who is common to all the contracts of the joint inputs,” the firm is a “contractual organization of inputs” (Alchian and Demsetz 1972).

Michael Jensen and William Meckling (1976) endorsed Alchian and Demsetz’s focus on contractual relationships, famously referring to the firm as a “nexus of a set of contracting relationships.” Jensen and Meckling highlight the “agency costs” introduced when Alchian and Demsetz’s unitary “monitor” is replaced by shareholders (with the residual claim) and a manager acting on their behalf. Jensen and Meckling argued that the problem of containing agency costs, present in all of the firm’s contractual relations, not simply those involving team production, better explained the role of the firm.

Jensen and Meckling stated that they viewed organizations such as the corporation as “legal fictions,” whereby the law considered an organization to be an individual, suggesting the artificial person theory. At the same time, however, they undercut the idea of the firm as an “entity” by claiming that trying to distinguish what was “inside” versus “outside” a contractual nexus did not make sense. In any event, legal scholars identify the “nexus-of-contracts” idea with the aggregate theory (Bainbridge 1997; Bratton 1989; Millon 1990). What is important is the content of the contractual relations among the parties, not the fictional nexus.

Margaret Blair and Lynn Stout (1999) present a team-production theory of the corporation, adding the idea of firm-specific investments to Alchian and Demsetz’s earlier work. Firm-specific investments are costly commitments to develop assets, including human assets, for a particular use, such that their value would be greatly reduced in any alternative use. Team members will make these investments up-front only if they have some assurance that they will receive corresponding benefits from the greater production value the investments make possible, and not have their efforts exploited after the fact.

Blair and Stout argue that their approach is consistent with contract theory, but stress the problems that team members would face in trying to account for all aspects of their interactions by means of explicit contracts. Contracts that provide, ex ante, a fixed allocation of the joint production to each member will encourage shirking; contracts that provide for ex post allocation are subject to rent seeking, as each team member tries to get a larger share of the produced value. Seeing these difficulties, team members can give up control of the assets and production to a third party, e.g., a corporation’s board of directors, who will allocate the corporation’s residual value among the members. Given that the corporation holds the residual, their theory might be thought of as a kind of “weak-form” entity theory, rather than as a contract theory.

p.246

Corporate governance

Theories of corporate identity pay a role in issues related to corporate governance. The nexus-of-contracts theory is widely understood to support a shareholder-centric view for the corporation’s directors. The contract theory identifies corporate law as private law, intended only to set the ground rules for the contracting parties, rather than public law, which could impose outside constraints, not simply on the corporation’s conduct but on its internal goals and organization. A sole fiduciary duty of directors to shareholders is not essential to the contract theory, however, as it views such duties as “corporate assets” that can be “bargained for and auctioned off” to others (Macey 2014). The entity view can be used to support the idea of broader duties by the directors. If corporate law is public law, then the corporate entity can be structured to mandate a stakeholder-centric view (Freeman 1984).9

Theoretical fitness

The accuracy of contract view as a descriptive theory of law has been strongly questioned. A major issue is the status of mandatory rules in corporation law. State incorporation laws allow for great flexibility in choosing the initial content of the articles of incorporation. However, there are some default rules that cannot be altered, such as quorum requirements for voting by directors or shareholders, or that share votes cannot be sold apart from the sale of the underlying shares (Easterbrook and Fischel 1991). Since the parties to a contract may set its terms without being subject to third-party interference by the state, the presence of mandatory rules in state incorporation laws has led to arguments that the contract theory does not fit the facts (Bratton 1989; Brudney 1985; Eisenberg 1999; Gordon 1989). Defenders have argued that the mandatory rules are unimportant or should be made optional (Bainbridge 1997; Butler and Ribstein 1990; Romano 1989).

Limited liability for shareholders of the corporation presents another issue of fit, one with more direct normative implications. Although state law provides limited liability to shareholders, the advocates of contract theory maintain that limited liability could be achieved purely by contract. Thus, these contract advocates [contractarians] do not view limited liability as a concession granted to a corporate entity by the state, but rather see the body of corporate law as a “standard form contract” (Easterbrook and Fischel 1991) in which limited liability is one term. Having a “standard form” provided by law is simply a convenience that could be replaced by having corporate officers insert limited liability clauses into every contract with the corporation’s creditors. Critics of contract theories, however, have argued that limited liability is the mark of an entity not an aggregate (Horwitz 1992).10 With the partnership, the paradigm of an aggregate association, partners had unlimited liability for the debts of the partnership.

For voluntary creditors, the contract advocates can point to both theory and historical practice. The voluntary creditor has the opportunity to assess the financial status of a would-be debtor company, to adjust the terms of credit accordingly, and to decide whether to enter a contract or not (Posner 1976). Historically, since the Bubble Act prevented joint-stock companies in England from incorporating, such companies were subject to the law of partnerships. These companies began to routinely insert clauses in their contracts with creditors limiting the liability of the members to the amount already invested in the company, and such clauses were upheld (Blumberg 1986).

p.247

Not all creditors are voluntary, however. The tort victim makes no choice to interact with the company (corporation or partnership), and has a claim against it, not for the payment of debt, but for damages. Tort claims are satisfied from the assets of the company, but, if the total claim exceeds the company assets, partners are liable to pay the difference from their other assets, while shareholders have no liability.

Contract advocates try to account for this difference in the treatment of involuntary creditors in various ways. Some (Hessen 1979; Pilon 1979) attempt to dissolve the problem by arguing that tort liability should fall only on those who actively “control” a business, regardless of whether it is a corporation or a partnership. Frank Easterbrook and Daniel Fischel (1991) argue that limited liability is economically efficient, at least for corporations with publicly traded shares; their implicit premise is that rules that, on balance, enhance welfare should be adopted. Larry Ribstein (1991) presents versions of both of these arguments.

These claims are contested even by some who are broadly accepting of the nexus-of-contracts view of the corporation. Thus, Henry Hansmann and Reinier Kraakman (1991) argue that a rule of limited liability is not economically efficient for either the close or publically-traded corporation as compared with a rule of proportional liability. Most analyses of the merits of limited versus unlimited liability assume “joint and several” liability, where each shareholder is liable for the entire claim. Under proportional liability, although liability is not capped, shareholders are liable only for the proportion of the claim represented by their proportion of the total shares.

Vicarious liability may also be based upon the receiving of benefits as well as control. Pilon (1979) tries to undercut this argument by claiming that the corporation’s benefit, its profit, is used to pay others (“creditors, customers, taxpayers”) as well as shareholders, and so would not confer vicarious liability uniquely upon shareholders. This argument, however, misunderstands the economic concept of profit: profit is what remains after all other contractual or legal claims are paid. As the residual claimants, only shareholders have the possibility of unbounded gains. For this reason, Sollars (2001) argues that shareholders should have proportional liability for tort claims in excess of a corporation’s assets.

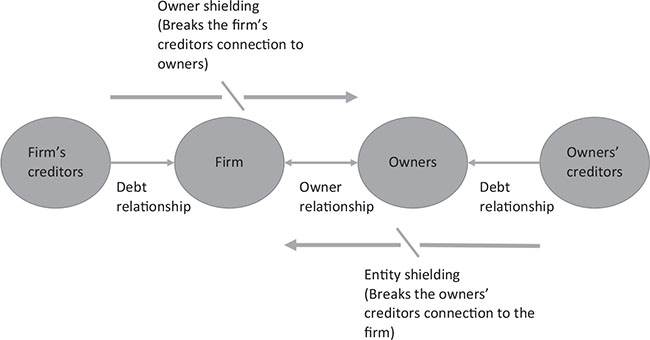

Whatever the relative merits of these arguments regarding limited liability, there is a more serious challenge to the idea that the corporation can be, or, failing that, should be viewed strictly as a composition of contracts. This comes from a different aspect of asset protection than limited liability, one that, although present through history, has only been analyzed relatively recently. Figure 14.1 presents the situation using the terminology of “owner shielding” and “entity shielding” (Hansmann and Kraakman 2000; Hansmann, Kraakman, and Squire 2006). When the role of the firm is played by a corporation, the firm’s creditors are unable to reach the personal assets of the shareholders; access is cut off by owner shielding. When the role of the firm is played by a partnership, the owners’ non-firm assets can be reached. Limited liability is the paradigm case of owner shielding.

There is, however, a different kind of asset shielding, one that is directed not at the creditors of the firm, but at the personal creditors of the firm’s owners. This is illustrated in Figure 14.1 by the term “entity shielding.” With entity shielding, the owner’s personal creditors are unable to reach the assets of the firm. Hansmann et al. (2006) argue that entity shielding is crucial to a firm being able to obtain credit. Without entity shielding, firm creditors face the risk that a creditor of any of the owners could disrupt the firm by pressing a claim that an owner might only be able to satisfy by means of liquidating her ownership interest. The corporation provides entity shielding to its shareholders since personal creditors of the shareholders are unable to reach the corporation’s assets.11

Although owner shielding or limited liability is available to the corporation with regard to voluntary creditors, at least in principle, by means of contract, Hansmann et al. (2006) argue that it is not possible to obtain entity shielding by contract. The reason is not simply because the transactions cost of inserting limiting terms in all of the contracts that potentially millions of owners have with each of their creditors is exponentially greater than the cost of putting analogous terms in every contract between one firm and its creditors. More importantly, each owner has a temptation to free-ride by omitting the limiting term from his personal credit contracts. While the firm’s cost of credit will be reduced if all owners ensure that the limitation term is in each contract with their personal creditors, each owner will individually obtain better credit from personal creditors by leaving out the term. This problem of collective action undercuts a potential firm creditor’s belief that an entity-shielding term has been included in every contract the firm’s owners have with their creditors. Hansmann et al. (2006) conclude that entity shielding must be viewed as a rule of property law, not available by contract.

p.248

Figure 14.1 Owner shielding vs. entity shielding.

Although this argument shows the inability of contract law to serve in principle as the sole foundation for corporate identity, it does not necessarily provide an argument for the real-entity theory. The corporation might still simply be an artificial person constructed by law. Arguments for the real-entity theory may be found, however, in discussions of corporate agency.

Can a corporation be a moral agent? In particular, is a corporation morally responsible, or, at least, liable for “its” actions? Is it proper to blame or praise a corporation for its actions? The theories of corporate identity discussed above play a role in answering these questions. With the aggregate theory, actions that might be ascribed to a corporation can be ascribed instead without loss of meaning to various natural persons who make up the aggregate that is the corporation in question.12 Any so-called corporate actions could be reduced without remainder to the actions of those persons. With the entity theory, a corporation itself acts, even if the actions of various persons are a necessary condition for that act. If the corporation itself acts, then it is at least logically possible that it can act morally (or immorally).

The possibility that the corporation is a moral agent seems to argue against the aggregate theory, and the artificial person (or concession) theory as well (Phillips 1992). Under the aggregate theory, corporate actions may be re-described as the actions of corporate directors, employees, or shareholders taken as permitted under the agreements or contracts that construct the corporation. Under the artificial person view, courts and legislatures may ascribe agency to various parties connected to the corporation with or without using a consistent moral underpinning. If a corporation is a real entity, however, then it is possible that it might take actions with moral import, which, whatever the law might say, cannot in fact be re-described as the actions of others.

p.249

Peter French (1979)13 embraces a strong form of the entity theory with the argument that a corporation is actually a moral person. He argues that a corporation is a moral person if it has intentions that cannot be properly attributed to the biological persons who compose it. A corporation has an internal decision (CID) structure, combining policy and decision-making, so that “[w]hen operative and properly activated . . . accomplishes a subordination and synthesis of the intentions and acts of various biological persons into a corporate decision” (French 1979). Further, French contends that “the melding of disparate interests and purposes gives rise to a corporate long range point of view.” Thus, a corporation may have its own intentions, and so be a moral person.14

Patricia Werhane (1985) endorses a weaker form, denying that intentionality is a sufficient condition for moral personhood, but accepting that a corporation is an entity that can nevertheless have moral responsibility.15 For Werhane, the corporation performs secondary actions that result from the primary actions of moral persons, but these secondary actions are not simply reducible to the primary ones. Corporate actions are not the sum of individual actions because “of the anonymity of the individual actions, the ways in which each is changed through the actions of others . . . and the ways in which goals are interpreted at each stage of activity” (1985). Thus, a corporation could take a (secondary) action that is immoral, even though it results from a “series of blameless primary actions” (1985).

Manuel Velasquez (2003) rejects the claim that a corporation is a moral person, taking issue, for example, with the idea that a corporation is a “real individual entity,” and with the claim that corporations manifest intentionality. Velasquez claims that arguments for real-entity status for corporations rely upon this premise: “(P1) If X has properties that cannot be attributed to its individual members, then X is a real entity distinct from its members” (2003).

This premise is false, he argues, because collections of objects X routinely have properties that do not hold for the members of X, yet we do not think that all such collections are entities. Even the property of a continuing identity over time is not enough for the corporation to be a real entity. Velasquez uses the example of a pile of sand replica of the “Great Pyramid of Cheops” that has some grains of sand carefully replaced so that its shape is retained. He states that, “clearly, the pile of sand is not an individual entity but merely an aggregate of entities” (2003).

The entity advocate might argue that Velasquez’s “clearly” simply reveals a competing intuition. Such an advocate might reply that “clearly” the pile of sand in the shape of the Great Pyramid is an individual entity. After all, Velasquez seems to refer to the Great Pyramid itself as an entity, yet it might be described as “merely” a pile of blocks. The advocate is concerned not with any property of X, but with those properties that provide some structure to X, for example, French’s CID, which are claimed to provide intentionality.

Regarding intentionality, Velasquez grants that intentions are attributed to groups, even in situations where the same intention cannot properly be attributed to members of the group. He dismisses this as metaphorical or “as if” intentionality. Thus, we may say that a car is “trying” to start or that a toy robot that continues to move its legs when stopped by an object “thinks” there is nothing blocking its path; but these are analogies, not a claim that the objects have “intentions and beliefs in any literal sense” (2003). The “intentionality” of corporate CID structures is no more literal than that of the car or robot.

p.250

William G. Weaver (1998) replies by taking the (metaphorical) bull by the horns, adopting a functionalist perspective. Relying on Daniel Dennett’s (1987) idea of the “intentional stance,” Weaver argues that corporations are complex enough systems to warrant ascriptions of the same sort of intention that we ascribe to arguably more complex human beings.

Velasquez claims to explain the attributions of intention to corporations without recourse to “ghostly group agents,” “group minds,” or “group intentionality” (2003). In his view, the burden is upon real entity theorists to prove his explanation incorrect. Velasquez claims that those arguing for corporate moral agency do so mostly through examples in which they argue individuals are blameless, yet something wrong has been done. When seen “with the eyes of an individualist,” however, these same examples reveal individuals morally responsible for the wrong (2003).

Entity advocates need not, however, argue from the existence of “ghost agents” or “group minds.” Nor are they committed to any premise like Velasquez’s P1. The motivation behind their examples is the concern that a wrong may occur that is not properly attributable to any of the individuals who make up a corporation, yet the corporation is in some way “attached” to the wrong. Thus, Philip Pettit worries that failure to hold a corporation responsible may leave a “deficit in the accounting books” (2007) of responsibility. If the corporation is a moral agent, then responsibility for the residual wrongdoing that remains after all individual responsibility has been properly allocated may be assigned to the corporation. Moreover, the possibility would exist that, by holding a corporate moral agent accountable for such wrongs, their occurrence could be minimized.

When no individual moral responsibility may properly be assigned, Velasquez’s (2003) response is that such incidents are simply cases of accidents, and the effects of treating them otherwise will be pernicious. Velasquez’s own example is that of National Semiconductor, which the Department of Defense claimed had falsified records to cover up inadequate semiconductor chip-testing procedures. The company agreed to pay a fine, but not to identify any individuals involved. The CEO claimed that the responsibility rested with the company as a whole, although there was evidence that pointed to at least some specific persons. The acceptance of corporate responsibility thwarted the possibility of banning certain culpable individuals from working on such projects in the future.

The potentially bad effects of a theory are not, however, an argument against its being true. Entity advocates can agree that individuals may be morally responsible in such situations, and perhaps some individuals should have been held accountable as well as National Semiconductor. Furthermore, advocates can at least point to the possibility that if corporate moral agency is ignored, there is a “perverse incentive” to mask or attenuate individual responsibility in the way that the internal relationships of a corporation are structured (Pettit 2007).

Entity advocate M.J. Phillips (1995) reworks French’s (1984) example of the Air New Zealand Mount Erebus crash. Phillips grants that in French’s account there is actually no left-over corporate responsibility for the crash; in Phillips’ re-imagining, each of several persons with some responsibility for informing the captain of Flight 901 of the changed conditions reasonably thinks that one of the others will do so. Apparently, then, the crash could have resulted from the interactions of various persons in the corporation, but no individual was responsible. Phillips notes, however, that such a situation of individuals with overlapping responsibilities is the result of the organization’s design, which, in turn, is attributable to some individuals. These individuals could suffer from the same kinds of excusing factors, e.g., “group think” and “risky-shift” (Phillips 1995) in the design activities that absolve the operations personnel from individual responsibility. If justifiable ignorance by persons responsible for an organization’s design may be excused from responsibility, why would it not excuse the corporation as well?

p.251

Phillips’s answer is that, if the corporation is an entity, then, given its network structure and information processing power, it can and should be held to a higher standard than individuals (1995). The problem with this claim is that the very cases Phillips wants to point to are those in which the corporation failed to foresee the consequences. Why is this evidence of corporate responsibility rather than evidence that, even with the “superhuman intelligence” (1995) of a corporation, the event was not foreseeable? Why should human beings, with their limited intelligence, believe that they can set the parameters of foreseeability for a super intelligence?16 In hindsight, of course, even ordinary human intelligence might see that a design change in the organization would have prevented some wrong. That the needed change was missing, however, is some evidence that the corporate “superintelligence,” as it was in fact structured, was not sufficient to foresee the problem. Perhaps corporations are entities with superintelligence, but our own limited intelligence leaves us without a way to determine a foreseeability criterion for their responsibility.

After his own detailed recounting of this decades-long debate, John Hasnas (2012) attempts to cut through the metaphysical knot of corporate moral responsibility by asking the pragmatic question of what purpose is served by attributing moral responsibility to a corporation. Hasnas argues that the reason must be in order to justify some kind of punishment. In punishing a corporation, however, we engage in collective punishment. As the prosecution of Arthur Anderson makes clear, the vast majority of the accounting firm’s employees suffered for an incident over which they had only the most tenuous connection. Hasnas sees corporate punishment, whether imposed to enhance corporate self-regulation or to denounce wrongdoing as violating the liberal Kantian principle that individuals may not be used merely as a means (2012).

Hasnas’ attempt to refocus the debate using the firm anchor of a shared Kantian insight might flounder, however, for Pettit (2007) seems quite willing to contemplate the propriety of collective punishment.17 Pettit distinguishes between making a proper ascription of moral responsibility to a person and punishing the person; his primary concern is with the degree of responsibility that is appropriate to attribute to a corporation rather than how it would be best punished. Thus, he holds that, retributivism is a “backward looking” doctrine “that bears primarily on when someone is fit to be held responsible in criminal law,” while consequentialism is a “forward-looking” doctrine of “how someone who is fit to be held responsible should be sanctioned” (2007). Arguably, then, despite Hasnas’ claim that the purpose of acknowledging corporate moral responsibility is to justify corporate punishment, Pettit might be seen as trying to properly account for the existence of a moral responsibility that is not exhausted by individual responsibility.

Pettit seems at places, however, to ignore his own distinction. He argues that even when there is no “deficit” in the total responsibility account to be filled by a corporate entity, there is reason to hold corporations responsible because of the “perverse incentive” mentioned above. However, such a concern is forward looking, undercutting a claim that his argument is only to establish the proper ascription of moral responsibility. Furthermore, Pettit stresses the importance of a forward looking “developmental rationale” (2007) that would prompt individuals to form a group in order that corporate responsibility could be properly applied.

Some other recent attempts to establish corporate moral responsibility include a “political” theory (Dubbink and Smith 2010) and a “non-agency” theory (Dempsey 2013). Wim Dubbink and Jeffery Smith (2010) argue for what they call a political account of corporate moral responsibility, based upon the need to maintain social coordination in a global business context where governmental regulation is ineffective. They view corporations as “administers of duty” that are capable of voluntarily incorporating moral principles into their decision making. Dubbink and Smith call their argument pragmatic, claiming to sidestep the contentious issue of whether a corporation can meet the requirements typically taken as necessary for individual moral responsibility.

p.252

At key points in their argument, however, they rely upon the idea that a CID—a corporation’s internal decision structure—provides the corporation with the ability to act on reasons, to act voluntarily, and to exercise a (limited) form of self-governance. The problem with these claims is that an opponent of corporate moral responsibility, such as Velasquez, would deny that the CID provides such capabilities to an entity, but rather is a description of rules governing individual interactions. Without facing a direct argument for the existence of a corporate entity, the opponent can deny any “deficit” in moral responsibility that requires corporate moral responsibility.

James A. Dempsey (2013) denies that the corporation is an intentional agent, but holds nevertheless that moral responsibility may properly be ascribed to it. He argues that “non-agential moral responsibility” may be ascribed to a corporation when it is sufficiently complex to generate a “remainder” responsibility over and above any individual responsibility. As noted above, however, remainder responsibility may be countered by the claim that a wrong was simply accidental, or that we lack the intelligence needed to specify a criterion of foreseeability for a corporation.

Dempsey claims that for some specific corporate rule it could be “impossible to determine . . . how given individuals should be held responsible for its existence and operation” (2013: 342). Unfortunately, the relation intended between “impossible” and “should” seems unclear. On the one hand, a given individual “should” be held responsible by actually holding him responsible; this cannot be impossible generally. On the other hand, the epistemic impossibility in some cases of determining which individuals had the responsibility does not imply that those unknown individuals do not bear all of the responsibility without remainder.

Concluding remarks

The initial concept of the corporation was a solution to the problem of how to retain property for some purposeful use over time. Recent scholarship has refined this idea by introducing the concepts of owner shielding, whereby a shareholder’s personal assets are protected from claims by corporate creditors, and entity shielding, whereby the corporation’s assets are protected from claims by a shareholder’s creditors. Analysis of the origins of the modern corporation suggest that the owner shielding provided by limited liability may not be a necessary feature of the corporation, but debate continues (Grundfest 1992; Hansmann and Kraakman 1992). Additional research concerning proportional liability might be helpful; this author is aware of only one historical analysis of the California situation (Weinstein 2005).

Regarding the debate between aggregate and real entity theories, although the aggregate theory, through the nexus-of-contracts concept, has arguably become the dominant view, the need for entity shielding has highlighted a crucial aspect of the corporation that is not contractual in nature. As for the matter of corporate governance, the team production theory of the corporation presents an exciting possibility for reconciling the shareholder-centric view of the corporation with the idea of increased discretion for board directors that is often associated with the stakeholder view. If director discretion increases the total value of a corporation by enticing more firm-specific investment, shareholders might prefer, somewhat paradoxically, that directors not have a shareholder-centric view.

No similar breakthrough seems near regarding the debate over corporate moral responsibility. Questions concerning the conditions for determining moral agency implicate basic philosophical disagreements over the nature of entities and actions that research in business ethics alone seems unlikely to settle.

p.253

Suggested readings

There is no single work that presents a history of the corporation from its genesis in ancient times to the present; the interested reader must focus on specific periods or topics. Standard references that treat aspects of the early corporation are E.B. Seymour, “The Historical Development of the Common-Law Conception of a Corporation” (1903), and Samuel Williston, “History of the Law of Business Corporations before 1800” (1888a). The English Bubble Act is analyzed in a paper by Ron Harris “The Bubble Act: Its Passage and Its Effects on Business Organization” (1994), and a book-length discussion is given by Richard Dale, The First Crash (2004). Phillip Blumberg, “Limited Liability and Corporate Groups” (1986), provides a comprehensive introduction to the history of limited liability in both England and the United States.

Readers interested in theories of corporate identity can begin with M.J. Phillips, “Corporate Moral Personhood and Three Conceptions of the Corporation” (1992). This essay combines ethical and legal perspectives in contrasting the artificial entity (or concession), real entity, and aggregate theories, while making clear Phillips’ preference for the real entity theory. The most influential statement of the real entity theory is given by Peter A. French, “The Corporation as a Moral Person” (1979). The starting point for the contemporary aggregate theory is the seminal “nexus-of-contracts” article by Michael Jensen and William Meckling, “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure” (1976). Their treatment is difficult for the non-economist, but more accessible discussions of the aggregate theory are given by Roger Pilon, “Corporations and Rights: On Treating Corporate People Justly” (1979), and William W. Bratton, “The ‘Nexus of Contracts’ Corporation” (1989).

Reading in corporate moral agency should begin with Peter A. French, Collective and Corporate Responsibility (1984) or “The Corporation as a Moral Person” (1979), which present the corporation as a fully-fledged moral agent, consistent with his view of the corporation as an entity with intentions. In Persons, Rights, and Corporations (1985), Patricia Werhane argues that the corporation is an entity with moral responsibility. Manuel Velasquez, in “Debunking Corporate Moral Responsibility” (2003), challenges the claim that corporations are entities with intentions. For aggregate theories that resolve ascriptions of corporate responsibility into those of natural persons, see Robert Hessen, In Defense of the Corporation (1979), and Roger Pilon “Corporations and Rights” (1979).

For further reading in this volume on philosophical justifications of property, see Chapter 18, Property and business. On the legal structures of non-profit corporations and corporations with a social mission, see Chapter 15, Alternative business organizations and social enterprise. On divergent views of the corporation and its relations to social responsibility, see Chapter 10, Social responsibility. On the nature of business, see Chapter 13, What is business?

Notes

1 Space allows for only a description of the business corporation as it developed in England and the US.

2 Walker (1931) suggests that the term stems from the practice of requiring guild members, beginning shortly after the Norman Conquest, to share purchases of goods with each other, paying out a common or joint fund.

3 This prohibition may seem unusual, given that the South Sea Company was itself incorporated. What has come to be called the “Bubble Act,” however, was passed by Parliament shortly before the crash, apparently largely through the lobbying efforts of the directors of the South Sea Company, who were concerned that the proliferation of unincorporated joint-stock companies would adversely affect the company’s ability to raise additional capital (Harris 1994).

4 The Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward, 17 US.518, 636 (1819).

p.254

5 Under the ultra vires doctrine a corporation could not take actions outside the scope of its charter. See, for example, Horwitz (1992).

6 The Trustees of Dartmouth College, 17 US at 643.

7 The Railroad Tax Cases: County of San Mateo v. Southern Pacific R. Co., 13 F. 722, 743–44 (1882).

8 Bratton (1989) holds that until late in the twentieth century the accepted doctrine used either the entity or aggregate theories depending on the “facts of the situation,” which is consistent with Dewey’s (1926) analysis.

9 Note, however, that Freeman (1984) argues that this viewpoint should be adopted voluntarily by corporate management.

10 Some contract advocates (Hessen 1979; Ribstein 1991) argue specifically against the concession theory. Even if limited liability is available by contract, however, some other version of the entity theory could be correct.

11 A shareholder’s creditor might be able to obtain the owner’s shares, but reaching corporate assets would require obtaining at least a majority of the shares.

12 One potential complication is that the identity of the persons who took the action(s) described as a “corporate act” could be unknown, either initially or after considerable investigation. Such a situation might legitimize talk of blaming a corporation (Pfeiffer 1995). A through-going proponent of an aggregate theory, however, could simply refer to “persons unknown who are members of the corporation.”

13 Partially in response to the criticisms that follow, French (1995) has modified his theory, and in later work refers to corporations as moral actors or agents rather than persons.

14 Ladd (1970) had previously argued that corporations could form intentions, but denied that their structure allowed them to form moral intentions.

15 Donaldson (1982) takes a similar position.

16 Hayek calls the idea that all the relevant facts could be known to one mind the “synoptic delusion” (Hayek 1973, 14–15).

17 Pettit (2007) states that “ascribing group responsibility will be all the more powerful, of course, if the ascription of guilt is attended by a penal sanction of some kind.”

References

Alchian, A.A. and H. Demsetz (1972). “Production, Information Costs and Economic Organization,” The American Economic Review 62:5, 777–95.

Anonymous (1702). The Law of Corporations: Containing the Laws and Customs of all the Corporations and Inferior Courts of Record in England. London: The assigns of Richard and Edward Atkins.

Bainbridge, S.M. (1997). “Community and Statism: A Conservative Contractarian Critique of Progressive Corporate Law Scholarship,” Cornell Law Review 82, 856–904.

Blair, M.M. and L.A. Stout (1999). “A Team Production Theory of Corporate Law,” Virginia Law Review 85, 247–328.

Blumberg, P.I. (1986). “Limited Liability and Corporate Groups,” The Journal of Corporation Law 11 (Summer), 573–631.

Bratton, W.W. (1989). “The ‘Nexus of Contracts’ Corporation: A Critical Appraisal,” Cornell Law Review 74, 407–465.

Brudney, V. (1985). “Corporate Governance, Agency Costs, and the Rhetoric of Contract,” Columbia Law Review 85, 1403–1444.

Butler, H.N. and L.E. Ribstein (1990). “Opting Out of Fiduciary Duties: A Response to the Anti-Contractarians,” Washington Law Review 65, 1–72.

Coase, R. (1937). “The Nature of the Firm,” Economica 4, 386–405.

Coase, R. (1960). “The Problem of Social Cost,” Journal of Law and Economics 3, 1–44.

Dale, R. (2004). The First Crash: Lessons from the South Sea Bubble. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Dempsey, J. (2013). “Corporations and Non-Agential Moral Responsibility,” Journal of Applied Philosophy 30:4, 334–350.

Dennett, D.C. (1987). The Intentional Stance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dewey, J. (1926). “The Historic Background of Corporate Legal Personality,” The Yale Law Journal 35:6, 655–73.

Dodd, E.M. (1948). “The Evolution of Limited Liability in American Industry: Massachusetts,” Harvard Law Review 61, 1351–1379.

p.255

Donaldson, T. (1982). Corporations and Morality. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Dubbink, W. and Smith, J. (2010). “A Political Account of Corporate Responsibility,” Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 14, 223–246.

Easterbrook, F.H. and D.R. Fischel (1991). The Economic Structure of Corporate Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Eisenberg, M.A. (1999). “The Conception that the Corporation is a Nexus of Contracts,” Iowa Journal of Corporation Law 24, 819–36.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, E.M. Epstein (ed.), Pitman Series in Business and Public Policy. Boston, MA: Pitman Publishing Inc.

French, P.A. (1979). “The Corporation as a Moral Person,” American Philosophical Quarterly 16:3, 207–15.

French, P.A. (1984). Collective and Corporate Responsibility. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

French, P.A. (1995). Corporate Ethics. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Gierke, O. (1913). Political Theories of the Middle Age, Frederick W. Maitland (trans.). London: Cambridge University Press. Original edition 1900, reprint 1913.

Gordon, J.N. (1989). “The Mandatory Structure of Corporate Law,” Columbia Law Review 89, 1549–99.

Grundfest, J.A. (1992). “The Limited Future of Unlimited Liability: A Capital Markets Perspective,” Yale Law Journal 102, 387–425.

Hamill, S.P. (1999). “From Special Privilege to General Utility: A Continuation of Willard Hurst’s Study of Corporations,” American University Law Reivew 49, 81–180.

Handlin, O. and M.F. Handlin (1945). “Origins of the American Business Corporation,” Journal of Economic History 5:1, 1–23.

Hansmann, H. (1996). The Ownership of Enterprise. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Hansmann, H. and R. Kraakman (1991). “Toward Unlimited Shareholder Liability for Corporate Torts,” Yale Law Journal 100, 1879–1934.

Hansmann, H. and R. Kraakman (1992). “Do the Capital Markets Compel Limited Liability? A Response to Professor Grundfest,” Yale Law Journal on Regulation 102, 427–436.

Hansmann, H. and R. Kraakman (2000). “The Essential Role of Organizational Law,” Yale Law Journal 110, 387–440.

Hansmann, H., R. Kraakman, and R. Squire (2006). “Law and the Rise of the Firm,” Harvard Law Review 119, 1333–1403.

Harris, R. (1994). “The Bubble Act: Its Passage and Its Effects on Business Organization,” The Journal of Economic History 54:3, 610–627.

Hartman, E.M. (1996). Organizational Ethics and the Good Life, R. Edward Freeman (ed.), The Ruffin Series in Business Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hasnas, J. (2012). “Reflections on Corporate Moral Responsibility and the Problem Solving Technique of Alexander the Great,” Journal of Business Ethics 107, 183–195.

Hayek, F.A. (1973). Law, Legislation and Liberty, Vol. 1, Rules and Order. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Hessen, R. (1979). In Defense of the Corporation. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

Horwitz, M.J. (1992). The Transformation of American Law, 1870–1960: The Crisis of Legal Orthodoxy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Jensen, M. and W. Meckling (1976). “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” The Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305–60.

Klein, W.A., J.M. Ramseyer, and S.M. Bainbridge (2006). Business Associations. New York, NY: Foundation Press.

Kyd, S. (1793). A Treatise on the Law of Corporations, 2 vols, Vol. 1. London: Printed for J. Butterworth.

Ladd, J. (1970). “Morality and the Ideal of Rationality in Formal Organizations,” The Monist 54:4, 488–516.

Laski, H.J. (1916). “The Personality of Associations,” Harvard Law Review 29:4, 404–26.

Macey, J.R. (2014). “Corporate Social Responsibility: A Law & Economics Perspective,” Chapman Law Review 17, 331–353.

Machen, A.W. (1911). “Corporate Personality,” Harvard Law Review 24:4, 253–67.

Maitland, F.W. (1905). “Moral Personality and Legal Personality,” Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation 6:2, 192–200.

Millon, D. (1990). “Theories of the Corporation,” Duke Law Journal 39:2, 210–262.

Pettit, P. (2007). “Responsibility Incorporated,” Ethics 117 (January), 171–201.

Pfeiffer, R.S. (1995). Why Blame the Organization?: A Pragmatic Analysis of Collective Moral Responsibility. Lanham, MD: Littlefield Adams Books.

p.256

Phillips, M.J. (1992). “Corporate Moral Personhood and Three Conceptions of the Corporation,” Business Ethics Quarterly 2:4, 435–459.

Phillips, M.J. (1994). “Reappraising the Real Entity Theory of the Corporation,” Florida State University Law Review 21, 1061–1123.

Phillips, M.J. (1995). “Corporate Moral Responsibility: When It Might Matter,” Business Ethics Quarterly 5:3, 555–576.

Pilon, R. (1979). “Corporations and Rights: On Treating Corporate People Justly,” Georgia Law Review 13 (Summer), 1245–1370.

Posner, R. (1973). Economic Analysis of Law, 1st edition. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Posner, R.A. (1976). “The Rights of Creditors of Affiliated Corporations,” University of Chicago Law Review 43 (Spring), 499–526.

Ribstein, L.E. (1991). “Limited Liability and Theories of the Corporation,” Maryland Law Review 50, 80–130.

Romano, R. (1989). “Answering the Wrong Question: the Tenuous Case for Mandatory Corporate Laws,” Columbia Law Review 89, 1599–1618.

Seymour, E.B. (1903). “The Historical Development of the Common-Law Conception of a Corporation,” The American Law Register 51:9, 529–51.

Shannon, H.A. (1954). “The Coming of General Limited Liability,” in E.M. Carus-Wilson (ed.) Essays in Economic History. London: Edward Arnold, 358–379.

Sollars, G.G. (2001). “An Appraisal of Shareholder Proportional Liability,” Journal of Business Ethics 32, 329–345.

The Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward (1819). United States Supreme Court, 17 US.518, 636.

Velasquez, M. (2003). “Debunking Corporate Moral Responsibility,” Business Ethics Quarterly 13:4, 531–562.

Walker, C.E. (1931). “The History of the Joint Stock Company,” The Accounting Review 6:2, 97–105.

Weaver, W.G. (1998). “Corporations as Intentional Systems,” Journal of Business Ethics 17, 87–97.

Weinstein, M.I. (2005). “ Limited Liability in California 1928–1931: It’s the Lawyers,” American Law and Economics Review 7, 439–83.

Werhane, P.H. (1985). Persons, Rights, and Corporations. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Williston, S. (1888a). “History of the Law of Business Corporations before 1800 (Part 1),” Harvard Law Review 2:3, 105–124.

Williston, S. (1888b). “History of the Law of Business Corporations before 1800 (Part 2),” Harvard Law Review 2:4, 149–166.