p.359

Regulation, rent seeking, and business ethics

Christel Koop and John Meadowcroft

In the autumn of 1979, US car maker Ford was struggling to compete with cheaper imports from Japan and was considering asking the US government for protection from this unwelcome foreign competition. Ford’s chief economist at the time, William A. Niskanen, wrote a memo to the company’s executives arguing that Ford should maintain its historic commitment to free trade. He stated that if Ford should lobby the government, it should be for the removal of existing tariffs on steel, engines and other components that the company presently imported (Simison 1980). Niskanen warned that the government did not give away special favours for free, so any protection the company secured would come with conditions attached that Ford would eventually regret. Moreover, he argued that for the business to seek special privileges from government would be morally wrong. He wrote: “A common commitment to refrain from seeking special favors serves the same economic function as a common commitment to refrain from stealing” (Simison 1980: 18).

Niskanen’s analysis suggests that business ethics—broadly defined as the “reflection on the ethical dimension of business exchanges and institutions” (Brenkert and Beauchamp 2010: 3)1—has an important place in the relationship between firms and governments. While, in the short term, a business or sector might benefit from protection from government, Niskanen argued that, in the long run, such special privileges would prove more costly than the steps required to make a business genuinely competitive. Moreover, he believed that businesses had a moral responsibility not to lobby government for special privileges and hence such behavior, while legal, was nevertheless unethical.

Niskanen’s account of ethical business practice would seem to contrast with Milton Friedman’s (1970) famous dictum that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” In an article that would introduce the shareholder theory in business ethics, Friedman argued that a business cannot have social responsibilities because only individuals have responsibilities. Questions about the social responsibility of businesses in fact amount to questions about the social responsibility of particular individuals. Corporate executives employed by firms are responsible to the shareholders of those corporations and those shareholders wish to see a return on their investment. To pursue other ends, Friedman argued, would be to put the agent’s interests over those of the principal and this would be morally wrong—business employees are employed to pursue their employer’s interests.

p.360

Friedman’s analysis would seem to condone businesses lobbying government in pursuit of special privileges. As long as such lobbying was done within the law and the award of special privileges increased the returns of shareholders then Friedman’s account of the appropriate role of business would seem to offer no basis to object. The executives at Ford appeared to have agreed with Friedman’s analysis, as they decided to ignore Niskanen’s advice and also decided that his services were no longer required.

Niskanen’s experience at Ford and Friedman’s injunction that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits” raise critical questions of business ethics in the relationship between firms and government, particularly given the size and scope of contemporary governments and their willingness to intervene in the economy. Governments in capitalist economies have the power to regulate business conduct in a number of ways.2 They may impose taxes on businesses, they may grant businesses subsidies, and they may introduce rules that prescribe certain types of business conduct, whether aimed at the production process or the products themselves. All of these regulatory tools can dramatically increase or decrease the costs of production, lead to the closure of or birth of whole industries, and significantly affect a country’s international competitiveness. Moreover, by using the regulatory tools at their disposal, governments may grant some businesses or sectors special privileges and protections—what are often termed “rents”—that may greatly influence the profitability of the firms so privileged vis-à-vis their competitors and affect the operation of the economy as a whole. In sum, governments can have a profound impact on business, and, consequently, on the fates of individual men and women. As George Stigler starkly put it:

The state—the machinery and power of the state—is a potential resource or threat to every industry in the society. With its power to prohibit or compel, to take or to give money, the state can and does selectively hurt or help a vast number of industries.

(1971: 3)

As intervention in the economy can take different forms, governments must decide how they are to deal with businesses, and businesses must decide how they are to deal with government. Much may depend on how governments understand businesses: as enterprises that involve the pursuit of private gain irrespective of the social consequences, thus requiring external intervention to ensure its activities are consistent with the public interest, or as enterprises that— wittingly or unwittingly—produce socially beneficial outcomes without the need for much external direction and control. How businesses approach their dealings with government may similarly depend upon how they understand the appropriate role of government and whether they believe lobbying government for particular regulatory regimes or special privileges—in other words, rent seeking—is morally right or wrong.

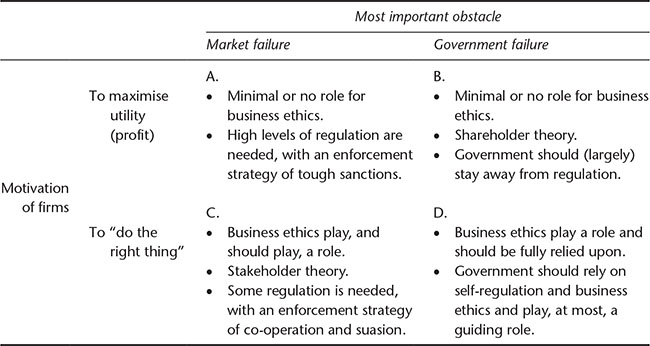

In this chapter we look at different ways of understanding the role of business in a modern economy, and the implications this has for business ethics, the appropriate scope and nature of government regulation, and the business ethics of rent seeking. We develop a two-by-two typology of views of regulation and business ethics based on 1) different perspectives on the motivation of firms, and 2) different perspectives on the type of obstacle—market or government failure—that is considered more detrimental to the economy. We link these perspectives to different (positive and normative) views of business ethics and government regulation. In the second section, we link the questions of business ethics and regulation to rent seeking—a prominent but controversial form of business engagement with the regulatory process. The scope and form of rent seeking may be contingent on economic calculations, but the decision on whether or not to engage in it will also depend on the motivation of a firm and its willingness to be involved in what some consider “inappropriate practices.” We conclude the chapter by reflecting on the policy implications of our analysis. Government regulation is nowadays ubiquitous. To the extent that businesses shape regulation with a view to their own special interests, the regulatory process can introduce new inefficiencies. We argue that institutional structures—governmental and corporate ones—may mitigate these problems, but are themselves highly sensitive, thus necessitating caution.

p.361

A typology of business ethics and regulation

Views of the role of business ethics in the economy—positive and normative—vary considerably from one part of the social science literature to another. Similarly, and partially following from these views, positions on the potential and desirability of government regulation vary. We argue that this variation can be attributed largely to differences in 1) perspectives on the motivation of firms, and 2) perspectives on the sort of obstacle that is most detrimental to the economy—market or government failure. In this section, we develop a two-dimensional heuristic typology linking perspectives on business motivation and economic obstacles to positions on the role of business ethics and government regulation. Our typology seeks to capture the most important variation in these positions and to clarify the sources of the variation.

The perspectives we distinguish are ideal-typical and many observers hold views that lie somewhere between the extremes. For instance, in their seminal work on Responsive Regulation (1992), Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite theorize the conditions under which different perspectives on the motivation of firms can be taken (see also Parker 2013). Nonetheless, as analytical constructs, the ideal types can help us identify the sources of views on regulation and business ethics as well as the position of these views in the broader debate on the topic.

Let us now turn to the typology itself. First of all, two ideal-typical perspectives on what actually drives business can be distinguished in the literature: 1) firms are amoral entities motivated by the maximization of purely economic goals, and 2) firms are moral entities driven by conceptions of appropriateness and legitimacy (cf. Ayres and Braithwaite 1992: 19; DeGeorge 2010: Ch. 1; Kagan and Scholz 1980). Underlying these perspectives are different logics of action: the “logic of consequences” and the “logic of appropriateness” (e.g., March and Olson 2008). Following the logic of consequences, action is driven by rational choice, cost-benefit analysis and utility maximization. As Thomas Risse puts it, “[t]his is the realm of instrumental rationality whereby the goal of action is to maximize or optimize one’s own interests and preferences” (2000: 3). The logic of appropriateness, by contrast, emphasizes the institutionalized environment in which action takes place. Action is motivated by the social norms and rules that apply to the situation; by “internalized prescriptions of what is socially defined as normal, true, right, or good, without, or in spite of calculations of consequences and expected utility” (March and Olson 2008: 689). In other words, actors seek “to do the right thing”—or to be ethical—rather than to maximize utility. The norms and rules do not only directly affect behavior, but they also constitute the identity and preferences of actors (Risse 2000: 4–5).

The logic of consequences is linked to a view of firms as utility maximizers; a view that is dominant in economics. Utility typically takes a very specific form; namely, the form of (expected) profit. This is most explicit in the assumption of profit maximization in the neoclassical theory of the firm. It is argued that firms seek to maximize profit since they crucially depend on it; otherwise, they risk going bankrupt or being subject to hostile take overs. Moreover, in modern corporations, with their separation of ownership and control, managers seek to maximize profit because it is this form of utility that the owners—with whom they have a fiduciary relationship—are interested in.

p.362

The assumption of profit maximization has not been without criticism. According to managerial theories of the firm, which focus on the role of managers, firms pursue other objectives than (just) profit maximization. Under conditions of organizational complexity, uncertainty and separation of ownership and control, managers may maximize their own personal utility rather than the firm’s profit (e.g., their salary, prestige, perks, or security) (e.g., Baumol 1962; Williamson 1963; cf. Jensen and Meckling 1976).3 The type of objective will also depend on organizational form, with considerable differences between for-profit and not-for-profit organizations and state-owned companies.

What most managerial modifications have in common with standard neoclassical models is the assumption of utility maximization. Though utility does not need to mean profit, it tends to be defined in purely economic terms. Indeed, action is assumed to follow a consequential logic. The models also all portray firms as amoral entities. Business conduct is driven by economic considerations; not by considerations of what is the right or ethical thing to do. This does not mean that firms are immoral: they may act morally, but only if it is, one way or another, economically beneficial. For instance, if companies can benefit from changes to the production process that lead to less pollution, or from introducing a strategy of corporate social responsibility, they are expected to choose these options. However, if companies can reduce their costs or increase their output by exploiting externalities in the form of pollution or exploitation of workers, they are expected to do so (see, e.g., Jensen 2002: 239). Even compliance with the law may be a function of economic calculation, with the law being disobeyed “when the gain derived from the crime exceeds the potential pain of being caught and punished” (Kagan and Scholz 1980: 356).

The economic conception of the firm as amoral entity—a conception that leaves little room for ethical reflection in business—is shared by some branches of the applied ethics literature and by many practitioners. First of all, it is shared by postmodern scholars who take an ethically nihilistic perspective on business, “contending that most of free enterprise is governed by executives and managers who only care about profits and their own well-being and think of ethical issues in business as either externalities or as irrelevant altogether” (Werhane 2012: 48–49). Second, it is represented in the shareholder theory of business ethics (e.g., Friedman 1970). As we set out below, this theory not only conceives of the firm as an amoral entity, but it also considers the limited scope of ethical reflection in business desirable. Finally, the conception is dominant in business itself, particularly in the Western world. For many observers, so Richard DeGeorge points out, “[corporations] are not unethical or immoral; rather, they are amoral insofar as they feel that ethical considerations are inappropriate in business” (2010: 3; italics original).

A different perspective on business motivation is presented by scholars who assume that rules of appropriate behavior play an important role in the economy. Sociological institutionalism, for instance, emphasizes that companies are deeply affected by the institutionalized environment in which they operate and that is governed by shared conceptions of what is normal and right (e.g., Meyer and Rowan 1977; DiMaggio and Powell 1983). This implies that ethics play an important role in business. This is echoed in what DeGeorge calls “the myth of amoral business” (2010: Ch. 1). The conception of the firm as amoral entity may prevail, but it is, according to DeGeorge, heavily flawed. Not only do scandals such as the Enron one suggest that we, as members of society, believe ethics should play a role in business, but the responses of businesses to ethical pressure by, for instance, environmental and consumer organizations, demonstrate that ethics do matter (2010: 4–5).

Much of the business ethics literature—and, as we set out later, particularly the stakeholder theory—regards firms as moral entities that base their choices on their (conscious or unconscious) assessment of what is appropriate for them to do in a specific situation rather than on cost-benefit analysis. In this context, firms are sometimes portrayed as seeking to act like “good citizens.” Though conceiving firms as citizens is not unproblematic—particularly in the case of multinational corporations—Pierre-Yves Néron and Wayne Norman find it useful as it captures the fact that “corporations are real members of some kind of our communities, with the power to contribute to or to diminish the common good, and the right to influence political and legal processes” (2008: 16; italics original). As such, the conception is relevant for empirical and normative analyses of firm behavior.

p.363

The concept of organizational legitimacy is also central in the “appropriateness perspective.” As John Meyer and Brian Rowan explain, companies are driven to incorporate—either ceremonially or substantially—practices and procedures that are associated with prevailing rationalized and institutionalized concepts of organizational work, even when conformity to institutionalized rules conflicts with efficiency criteria (1977: 340). Conforming to the rules, so Mark Suchman points out, can lead companies to be regarded as “natural and meaningful” and can “increase their legitimacy and long-term survival prospects, independent of the immediate efficacy of the acquired practices and procedures” (1995: 576). Crucially, the practices are introduced for reasons of appropriateness rather than for instrumental reasons, even though they can enhance firms’ survival (cf. Bowie 1999: 120–121).

The question of what sort of behavior we should expect is somewhat open if we take the second perspective. Firms would do what is considered to be “right” in a given situation, but conceptions of what is right may vary over time and across countries and sectors. That is, firms are generally expected to incorporate “good practices” such as ensuring health and safety at work, protecting consumers and the environment, and committing themselves to some of corporate social responsibility, but there will be context-specific variation. Also, firms are, in general, law-abiding, particularly if the law reflects socially shared conceptions of what is normal and right. Yet, if laws are considered to be inappropriate—for instance, because they are regarded as arbitrary or unreasonable—companies may “rebel” (cf. Kagan and Scholz 1980: 360).

The distinction between the two perspectives of business motivation is, so we argue, crucial to but not sufficient for a good understanding of the variation in views of business ethics and regulation. A second analytical distinction is needed; one that follows from the question of whether market or government failure is the more important obstacle to a well-functioning economy. Market failure refers to situations where resources are not allocated in the most efficient way; in other words, where market activity leads to outcomes that could still be improved upon from a societal perspective (see Bator 1958). Examples include monopoly power, negative externalities, predatory pricing and other forms of anti-competitive behavior, and information inadequacies. Government failure, by contrast, is about situations in which government intervention in the economy creates allocative inefficiencies. Capture by industry is the best-known source, but failure may also result from excessive bureaucracy, information asymmetry between regulators and regulatees, coordination problems, and policies that enhance anti-competitive behavior, moral hazard, overcapitalization, and crowding out (e.g., Majone 1994: 79).

The first ideal-typical perspective emphasizes market failure as the crucial obstacle. We find this perspective in a rather pure form in public interest-based approaches to policy-making, where (regulatory) policies are considered to be introduced for reasons of public interest, including the creation of markets and the correction of market failure (see Baldwin et al. 2012: 41–42). The perspective also prevails in the business ethics literature, which focuses much more on market failure than on government failure (cf. Jaworski 2013). Market failure is, in these literatures, seen as a major problem for the economy, while government failure is largely assumed away. Policy makers are regarded as capable and willing to act in the public interest, as well as trustworthy and disinterested. They may act in the public interest for reasons of appropriateness, but their “responsiveness” may also be a consequence of institutionalized mechanisms such as elections. Moreover, the attitudes may be public sector-specific, as argued in studies on public sector motivation (e.g., Perry and Wise 1990). All in all, as Robert Baldwin and his colleagues put it:

p.364

It is a vision that implies a highly benevolent view of political processes. It assumes some form of objective knowledge that can establish the presence of ‘market failure’ and that can respond with the appropriate instruments. The ‘public interest’ world is a world in which bureaucracies do not protect or expand their turf, in which politicians do not seek to enhance their electoral or other career prospects, in which decision-making rules do not determine decisions, and . . . in which business and other interest groups do not seek special exemptions or privileges.

(2012: 41)

The alternative holds that government failure is the key problem: markets may not always be perfect, but government intervention leads to worse outcomes. Explanations of government failure focus on the role of (private) interests or on the role of policymakers’ (lack of) knowledge. Public choice (or private interest) approaches criticize the assumption of disinterested policy makers, arguing instead that the latter—like everyone else—seek to pursue their own interests rather than some sort of public interest. While politicians seek to maximize re-election chances, bureaucrats aim to maximize their budget, turf or autonomy.

This perspective has been most famously advanced in the so-called “economic theory of regulation,” which centers on regulatory capture as failure. The theory was introduced by Chicago school economist George Stigler (1971), and further developed by authors such as Sam Peltzman (1976). Stigler’s core and still prominent argument is that “as a rule, regulation is acquired by the industry and is designed and operated primarily for its benefit” (1971: 3). The author explains that both industry and other interest coalitions put effort into averting unfavorable policy outcomes, but industry is more successful in shaping policy because it is more concentrated, more resourceful, and more vigorous in exercising pressure for it has more to lose (cf. Olson 1965). Policy makers, on the other hand, will give in to industry demands because they are either indifferent or electoral beneficiaries.

Concerns about government failure may also be knowledge-based. Even if policy makers wish to pursue the public interest, they may not be able to do so because of insufficient information or an insufficient capacity to process the information. At a general level, the argument is that allocative efficiency is hard to identify and achieve; for instance, because there are multiple and clashing conceptions of the public interest (Baldwin et al. 2012: 42). A more specific mechanism behind government failure is presented by F.A. Hayek (1945). Hayek argues that information about economic needs and preferences is incomplete and dispersed among many people, which is why it is impossible for government to design a system that is capable of collecting and analyzing all pieces of information, and responding quickly to changes. The market, on the other hand, can coordinate economic activity by means of its price system, “a kind of machinery for registering change, or a system of telecommunications which enables individual producers to watch merely the movement of a few pointers . . . in order to adjust their activities to changes of which they may never know more than is reflected in the price movement” (1945: 527). Hence, markets can achieve much higher levels of allocative efficiency than governments can.

Combining the different perspectives, we can come to four different positions on the role of business ethics and regulation. These positions incorporate positive as well as normative elements, and are summarized in Table 21.1.

p.365

Table 21.1 Views of business ethics and regulation.

The upper left-hand cell (Type A) brings together a view of firms as utility maximizers with a view of market failure as the key obstacle to the functioning of economies. This combination of perspectives is prominent in those parts of the economics literature that focus on market failure and regulation—that is, parts that do not assume perfect markets. The view of firms as economic utility maximizers does not leave much room for ethical considerations—business ethics are not (or hardly) considered to play a role. Yet, letting firms operate in the way they naturally tend to operate leads to suboptimal economic outcomes as market failures will be exploited. Therefore, high levels of government regulation are needed to avoid market failure. Self-regulation by industry, on the other hand, cannot be relied upon as it will be used in the interest of the industry; for instance, to protect the industry from competition by making it harder for new entrants to enter the market. Government failure is not or hardly taken into consideration. Moreover, as firms are seen as driven by cost-benefit analyses that are also used to determine whether or not to comply with the law, an enforcement strategy that focuses on hard sanctions is needed. That is, only by making sure that compliance pays off can government regulation be successful; any other strategy will be exploited (see Kagan and Scholz 1980: 354).

A rather different view of business ethics and regulation can be found in the upper right-hand cell (Type B). Observers here are associated with the same conception of firms as utility maximizers, but government failure is considered to be the key problem. The economy, according to this view, works most efficiently if we let firms maximize their economic utility. Ethics do not play a role in business, and this is how it should be as ethical considerations may move firms away from utility maximization and may, thus, lead to suboptimal outcomes. Such a view is traditionally associated with Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations:

As every individual . . . endeavours as much as he can both to employ his capital in the support of domestic industry, and so to direct that industry that its produce may be of the greatest value; every individual necessarily labours to render the annual revenue of the society as great as he can. He generally, indeed, neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it. By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for society that it was not part of it. By pursuing his own interest, he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.

p.366

(1981 [1776]: IV.ii.9)

Smith puts emphasis on the positive externalities of utility maximization by economic actors. Government, on the other hand, should be minimal and should largely stay away from the regulation of business. Regulation would make things worse as it moves the focus of business away from competition and towards co-operation to extract favors from government, for which the consumer pays the price.

In a similar vein, Friedman (1970) advises not to move away from the maximization of utility and, in particular, the maximization of profit. He argues that corporate executives are responsible for conducting business in accordance with the preferences of their principals—the owners—who typically have an interest in profit maximization. Friedman’s argument does not end here, though: firms’ pursuance of other interests than those of the owners may reduce economic efficiency. That is, promoting “desirable social ends” is a form of taxing and spending; yet, corporate executives have neither the authority nor the expertise to engage in such activities. Thus, serving broader interests may lead to worse outcomes than serving the interests of the owners. Following from this, the shareholder theory in business ethics states that it is the responsibility of corporate managers to act according to the preferences of the shareholders, and thus to maximize profit.4

The next cell (Type C)—at the lower left-hand side—captures conceptions of firms as moral entities combined with concerns about the detrimental effect of market failure. Even though firms seek to be “good citizens,” market failure—which is more of an unintended consequence here—is a crucial problem. Following these views, some government regulation is needed, but self-regulation can also be relied on, with business ethics playing, and having to play, an important role (cf. Norman 2011). Moreover, if government regulation can take forms that enhance ethical reflection and “good behavior” by firms, such forms should be preferred for they are more effective and efficient (Ayres and Braithwaite 1992: Ch. 2). Equally, the preferred enforcement strategy is one based on co-operation and persuasion, including reminders of what “good citizenship” looks like. Such a strategy will be more successful than a strategy of deterrence (as advocated under Type A) as the latter undermines companies’ good will and sense of responsibility.

This position characterizes many approaches to business ethics, and the stakeholder theory in particular. Developed in various forms by authors such as Edward Freeman (1984), Archie Carroll (1989) and Norman Bowie (1999), the theory emphasizes firms’ responsibility towards a broad range of stakeholders, not just shareholders. These include at least employees, customers, suppliers, and the local community, and sometimes also the media, government, special interest groups, and competitors (e.g., Freeman 1984: 25). The theory has a normative, instrumental and descriptive dimension (Donaldson and Preston 1995). The normative argument is that firms—and managers in particular—have moral obligations towards different categories of stakeholders. The key moral dilemmas in business are, consequently, about reconciling obligations in cases where stakeholders have conflicting interests (Heath 2014: 68). The normative foundations are somewhat diverse, with authors having relied on, for instance, Kantian and Rawlsian ethics (e.g., Bowie 1999; Evan and Freeman 1988; Phillips 1997). The theory also has an instrumental dimension, with authors linking, though not always demonstrating, the stakeholder focus to organizational success and survival (e.g., Freeman 1984; Bowie 1999: 120–121; cf. Jensen 2002). In other words, taking ethics into consideration can lead to better outcomes for the firm. Finally, in descriptive terms, the theory seeks to explore stakeholder relations, holding that firms do, indeed, act upon their obligations towards various stakeholders. In other words, firms are moral entities that are not (solely) driven by economic utility maximization.

p.367

Even more directly representative of Type C is Joseph Heath’s (2014) market-failures approach to business ethics. Heath not only argues that firms are moral entities, but also focuses attention on the detrimental effect of market failure. He points out that the purpose of the market is to promote Pareto efficiency, and such efficiency can be seen as a virtue because of its win-win characteristic (2014: 3). Indeed, we value the profit orientation of firms because it contributes to competition in the market and, thus, to Pareto efficient outcomes. Yet, only in some circumstances does the market produce efficient outcomes by means of an “invisible hand”; most areas of economic activity suffer from market failure. Therefore, government regulation is introduced. But regulation cannot deal with all imperfections: regulatory policies are characterized by imperfect contracting, while high levels of regulatory enforcement are too costly (2014: 16). This is where moral obligation enters: insofar as regulation leaves open the possibility of exploiting market failure, firms have the ethical responsibility to refrain from such behavior and to comply beyond the law.

Finally, the lower right-hand cell (Type D) combines an emphasis on government failure with a view of business firms as “rule-followers.” This position is not prominent in the literature, but is fully compatible with the view that ethics can and should play a crucial role in the economy. Firms are not only considered to have most knowledge of their own market, but they are also seen as moral entities seeking to do the right thing. This puts firms in a perfect position to contribute to “moral markets” (cf. Zak 2008). Government intervention in the economy should be limited as such intervention is likely to enhance rather than correct distortions of the price signal.5 Such government failure is not so much the result of policy makers pursuing their own self-interest, but rather a consequence of knowledge problems and unintended consequences of intervention. Policy makers may seek to pursue the public interest, but are prevented from doing so because of, for instance, a lack of knowledge of the sector. Only light forms of regulation that are voluntary in nature may find support here as these may serve as a reminder of what ethical behavior in business is. For instance, governments may want to introduce voluntary environmental standards or promote strategies of corporate social responsibility.

The business ethics of rent seeking

Government regulation incentivizes firms to engage with governments (and regulatory agencies) to try to influence the regulatory process, including by means of individual or collective lobbying. Business engagement with the regulatory process—whether initiated for economic or ethical reasons—may help ensure that regulation efficiently and effectively targets market failure. Businesses may provide sector-specific information about how the market works and what the implications of different types of interventions may be, and this may reduce the likelihood of government failure. Yet, business involvement in the regulatory process may also lead to the promotion of special interests, and this may shift regulation away from what is most beneficial for society. Such attempts to frame regulations in a way that is beneficial for individual businesses are usually described as an example of rent seeking: “non-voting, non-criminal activities that individuals or firms engage in with the purpose of either changing the laws or regulations, or how the laws and regulations are administered, for the purpose of securing a benefit” (Brennan 2016: E3).

p.368

Rent seeking constitutes one of the most prominent and controversial forms of business engagement in politics and policy-making. In economic theory (as opposed to everyday language), a rent describes a payment made to the owner of a resource over and above what that resource could command in an alternative usage. Rents may be found in commercial settings: for instance, the sole baker in a remote village sets the price for bread to maximise profits and, in the short term, may be able to reap exceptional returns if there is no convenient alternative source of bread; but, in the long term, the existence of exceptional profits should motivate other producers to establish competing bakeries or inspire consumers to source alternative supplies of bread or substitute products. In this way, over time, market competition should eliminate economic rents. In the marketplace, rent seeking is said to have socially beneficial consequences because it acts as a spur to entrepreneurial activity that dissipates rents. The overall outcome of this process is increased efficiency as resources move to more productive uses as signalled by the utility-maximizing activities of producers and consumers.

In the political realm, however, rent seeking is generally understood to be more pernicious. Political rents do not exist “naturally,” but are deliberately created by government, usually via the allocation of a monopoly right or special privilege to a particular individual, group or firm. For example, a car manufacturer may try to persuade the government to ban foreign imports; or milk producers may lobby for government subsidies to protect their profits. In contrast to economic rents, once a monopoly right or special privilege has been granted, it may be exploited repeatedly, with little prospect of erosion or dissipation. As political rent seeking is institutionalized, it does not trigger the same competitive processes as economic rent seeking. Rather, the removal of political rents will require political action, but as vested interests are created in the process of rent seeking, such change may be hard to achieve.

Until very recently there was almost no discussion of the ethics of corporate rent seeking in the business ethics and corporate social responsibility literature. This led John Boatright to conclude that “[e]ither there is nothing morally wrong with rent seeking, or the moral wrong in rent seeking has escaped attention” (2009: 541). A notable exception to the neglect of rent seeking in discussion of business ethics has been Heath’s (2014) market-failures approach to business ethics. As described above, according to this approach businesses should refrain from engaging in activities that create market failures. Rent seeking—for example, seeking a monopoly privilege from government—is said to create a market failure because it introduces inefficiencies into the marketplace and for this reason business managers should eschew such behavior.

Peter Jaworski (2013) has objected that Heath incorrectly classifies rent seeking as a market failure when it should properly be understood as a government failure:

Tariffs and protectionist measures, and, we might say, the successful extraction of rents in general when they contribute to socially inefficient outcomes, cannot be described as a market failure. Instead, these are properly described as instances of government failure . . . the choice to grant these special favours to certain firms is controlled not by market, but by government actors and institutions.

(2013: 4; italics original)

Nevertheless, Heath and Jaworski are in agreement that rent seeking constitutes unethical behavior. Jaworski’s intention is to highlight the essential role of government in the process of rent seeking. For Jaworski, the “primary wrong” in rent seeking is the actions of “public agents [who] violate their duties to be good stewards or effective custodians of tax dollars” by distributing rents (2014: 475). But he also argues that rent seekers themselves should bear some of the responsibility for the social costs imposed by rent seeking:

p.369

Just as it would be wrong for me to try to pressure my doctor to write me a prescription for painkillers, so it would be wrong for businesses to try to pressure public actors to create or distribute rents that generate social waste, or promote market inefficiencies.

(2014: 475)

It is surely legitimate and even desirable for businesses to be involved in the process via which government regulates their sector of the economy, but the ethical question raised by Jaworski concerns how businesses should balance their own interests and the interests of others (e.g., competitors, consumers) in their interactions with government. If businesses have specialist knowledge that regulators (or their political principals) do not possess, should they exploit the information asymmetry to frame regulation in their interests in ways that would constitute rent seeking?

To answer this question, it is necessary to identify the moral wrong(s) that have led scholars to judge rent seeking to be unethical. Rent seeking is usually considered unethical for two principal reasons: 1) it is economically wasteful; and 2) it involves the exploitation of those who must pay for the rents obtained.

Rent seeking is considered economically wasteful because resources devoted to it could have been put to an alternative use and, as such, rent seeking imposes opportunity costs that may hold an economy within its production possibility frontier—in other words, make society poorer than it would be otherwise. Indeed, it has been argued that a definitional characteristic of rent seeking is that it is inherently wasteful. Nobel laureate James Buchanan, for example, stated that, “[t]he term rent seeking is designed to describe behavior in institutional settings where individual efforts to maximize value generate social waste rather than social surplus” (1980: 4; italics original).

The assimilation of rent seeking and waste originates in the first conceptualisation of rent seeking in response to Arnold Harberger’s (1954, 1959) analysis of the social cost of monopoly. Prior to Harberger’s work economists assumed that the welfare losses resulting from monopolies were relatively large, but Harberger’s formal and empirical analysis suggested that previous research had significantly over-estimated these costs. According to Harberger, the “additional” income derived by monopolists from the higher prices consumers paid compared to a genuinely competitive market was a zero-sum transfer from consumers to producers that did not impose a cost on society as a whole. The social cost of monopoly, therefore, was simply the opportunity cost of the trades that were foregone because consumers expended resources paying inflated monopoly prices.

Gordon Tullock’s (1967) ground-breaking article first applied (what has become known as) the concept of rent seeking to challenge Harberger’s calculation of the social cost of monopoly. Tullock argued that it was a mistake to regard transfers as zero-sum without any accompanying social cost. While one can formally show, as Harberger did, that transfers simply move resources from one individual to another with no apparent net loss to society, Tullock argued that such an approach failed to take into account the fact that the availability of transfers led people to invest resources in seeking transfers or attempting to prevent transfers.

Tullock (1967, 1971) used the analogous case of theft to illustrate the error of Harberger’s approach. In economic terms, theft is a transfer that “produces no welfare triangle at all, and hence would show a zero social cost if measured by the Harberger method” (1967: 228). But it does not follow that theft is costless to society because individuals expend resources in the activity of theft and in protecting themselves against theft. Such expenditure imposes opportunity costs on society—that money could have been spent on alternative uses. The expenditure of resources in the pursuit of transfers, and in resisting transfers away, has become known as “Tullock Costs,” in recognition of Tullock’s role in establishing the scholarly literature in which these costs are identified and analysed. Tullock Costs are the costs of rent seeking, separate and above the costs of monopoly identified by Harberger.

p.370

It is argued that the presence of Tullock Costs means that rent seeking is always negative-sum because resources are spent in the pursuit of rents and in attempts to avoid rent extraction. The costs of rent seeking include the resources expended by successful and unsuccessful rent seekers, as well as resources spent resisting the rent seeking of others (Krueger 1974; Tollison 1982; Fang 2002). It would then appear to be simply axiomatic that resources spent on rent seeking constitute a loss to society. In the words of William Mitchell: “It is readily apparent that whenever a more valued employment is possible, something is being ‘wasted’” (1990: 95). Rent seeking, then, is considered unethical because it is essentially unproductive from society’s point of view; it is simply the expenditure of effort in the attempt to capture a share of already existing resources.

Rent seeking is also claimed to be unethical because the already existing resources that rent-seekers attempt to capture have been produced by others, so that if rent seeking is successful then those producers will have worked to produce a benefit that others will consume. Hence, rent seeking is said to involve the routine exploitation of large sections of the population by organized interest groups who harness the power of the state to extract benefits funded by others (e.g., Buchanan 1996; Clark and Lee 2006). According to Buchanan, when “[a] coalition of special interests, each with concentrated benefits, can succeed in majoritarian settings in imposing generalized costs on all members of the polity,” this constitutes “the exploitation of the many by the few” (1996: 71; see also Brennan and Buchanan 1980; Buchanan and Congleton 1998).

Normative weight may be added to this claim by the fact that rent extraction tends to be either horizontal, involving transfers from one non-poor group to another, or regressive in that the poor will pay a higher proportion of their income in rents than the non-poor. Higher food prices as a result of subsidies to farmers, for example, will have a greater impact proportionately on the incomes and living standards of the poor than the non-poor because the former spend a greater proportion of their income on essentials like food (e.g., DeBow 1992: 11–12; Rodríguez 2004).

Rent seeking is therefore deemed morally wrong because it involves the imposition of costs on others to produce the benefit consumed by the recipient of the rent. It is for this reason that Niskanen in his advice to Ford discussed at the outset of this chapter, and in accordance with the views of many other economists and political scientists, argued that businesses should refrain from rent seeking, even if such actions were not illegal and would be in the financial interests of the firm. It may also be significant that Milton Friedman (1962, Chapter IV) argued against government protections and special privileges for business in the form of monopolies, tariffs and subsidies. This suggests that even on Friedman’s own terms the social responsibility of business is not as clear-cut as his famous article would suggest; it would seem to follow from Friedman’s opposition to the government allocation of protections and special privileges that business managers and shareholders do have a moral responsibility not to engage in rent seeking, even if such behavior is perfectly legal.

Setting out the moral wrong usually identified in rent seeking does not end the ethical analysis, however. Separating rent seeking from contributing to the regulatory process, for example, may be difficult. Safety regulations, for example, may genuinely help to protect consumers from hazardous products, but may also create costs of market entry that shield incumbent firms from market competition. If a firm participates in the regulatory process that creates regulations that have both public and private benefits, should it be considered a public-spirited contributor to regulation or an immoral seeker of special privileges? As it stands, there has been very little theoretical or empirical engagement with such nuances concerning the appropriate relationship between government and business in contemporary economies.

p.371

Regulation, rent seeking, and institutional design

In a context in which regulation is at least partially embraced by government, businesses have to decide how they are to deal with the regulatory process. On the one hand, we have observed that the presence of regulation triggers engagement aimed at avoiding or shaping the rules; on the other hand, business engagement may itself lead to new or expanded regulation that, at least partially, serves the industry that lobbied for it. Rent seeking may be the most contentious and prominent form of industry-serving government intervention. However, there is widespread agreement in the economic literature that rent seeking is wasteful and involves the exploitation of those who fund the rents created. From an ethical perspective, it is also hard to justify rent seeking. Yet, once we accept that ethics matter—that is, once we accept that firms are (also) moral entities—the scope of rent seeking may not be as large as the economic argument suggests. That is, we should expect there to be a category of firms that care about ethical behavior and largely refrain from rent seeking for these reasons, even if they could conceivably benefit from it economically.

Nonetheless, empirical analysis suggests that rent seeking takes place on a large scale. This raises the question of whether and how government can deal with it. One answer is that there should be no more regulatory intervention—or no more intervention targeting specific groups in society. As it depends on the existence of regulation, rent seeking may indeed disappear. However, if we accept that market failure is a problem, and that regulation has the potential to reduce such failure, we may lose something important in the process. Another answer, therefore, is that we should focus on institutional design—both in a formal and an informal sense.

First, the regulatory process itself may be formally regulated so as to avoid rent seeking. That is, to the extent that policymakers are interested in escaping rent seeking, they may introduce structures that institutionalize their commitment to stay away from rents. This may take broadly two forms. On the one hand, business engagement in the regulatory process can be reduced by getting rid of lobbying, revolving doors and other mechanisms that can facilitate rents. Yet, besides the fact that this is difficult if not impossible to implement, it will also reduce the sector-specific expertise that business engagement contributes to regulatory policies. On the other hand, business engagement can be balanced by actively broadening the range of interests that are involved in the regulatory process. This may, for instance, take the form of requirements in terms of diversity of the background of the members of executive, supervisory or advisory boards, or the form of the (financial or other) support for consumer organisations. It may also take the form of transparency requirements, which make it more challenging for businesses to convince policy makers to grant them favours. Yet, the second strategy is not easy: getting the balance right is notably difficult and incumbent business interests may still be de facto dominant.

Second, governments may seek to strengthen informal institutions—including norms—that make rent seeking less attractive. If rent seeking can be challenged on ethical grounds, norms of appropriate business behavior may be emphasized in the regulatory process and, based on the literature on suasion, firms may be regularly reminded what constitutes “good citizenship.” Yet again, this is not straightforward. As the literature on “responsive regulation” suggests, a strategy of suasion may work for some companies, but could be exploited by other companies that prioritise profit-making (e.g., Ayres and Braithwaite 1992).

Clearly, designing institutions to avoid rent seeking is a major challenge, and we may never fully solve the problem. An important note of optimism may be injected if we consider that the literature on rent seeking was developed during the second half of the twentieth century when the scope and size of the state was expanding throughout the Western democracies. The economists and political scientists who first studied rent seeking saw it as an important driver of that state expansion; that is, demands for more state intervention, protections and privileges were judged to be leading to bigger and bigger government. The trajectories of contemporary democracies towards ever-bigger government were thought by some scholars to even threaten economic and political freedom (Hayek 1944; Olson 1982). But, in fact, from the standpoint of the present, it can be seen that many states have shrunk since the 1970s and 1980s; the empirical evidence seems to show that when rents reach a certain level then counter-veiling pressures will emerge that can lead to a process of rent destruction. Rent seeking, then, may rise and fall in a cyclical manner (Alves and Meadowcroft 2014; Murphy et al. 1993).

p.372

Concluding remarks

The relationship between government and business is an essential feature of the modern economy. Government regulation of the economy may have the potential to solve market failures, but it also has the potential to introduce new pathologies—what are known as government failures. It is important, then, to judge the relative merits of intervention and non-intervention; the potential costs of market failure and government failure.

The temptation to seek rents, like the temptation to steal, will likely always be present. Moral injunctions against rent seeking, like moral injunctions against theft, may be effective to deter some people from rent seeking, but institutional design that takes seriously the problem of government failure, as well as the problem of market failure, will surely also be necessary.

Essential readings

In their book, Responsive Regulation, Ian Ayres and John Braithwaite (1992) build on the differences in motivations of firms to develop their influential theory on responsive regulation. Robert Baldwin, Martin Cave and Martin Lodge cover the full scope of the positive study of regulation in Understanding Regulation (2012). In Morality, Competition, and the Firm (2014), Joseph Heath takes market failure as the guiding principle for regulation as well as for business ethics and engages with the idea of rent seeking. The classic articles on the theory and practice of rent seeking are those by Anne O. Krueger, “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society,” (1974) and Gordon Tullock, “Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies and Theft” (1967).

For further reading in this volume on the ethics of rent seeking, see Chapter 7, Can profit seekers be virtuous? On the nature of the business firm and the motivation of business agents, see Chapter 13, What is business? For a discussion of economics and market failures, see Chapter 17, The contribution of economics to business ethics. On the contribution of US government policy toward the economic crisis of 2008, see Chapter 23, The economic crisis: causes and considerations. For discussions of recent instances of the intersection of politics and markets, see Chapter 35, Business ethics in China; Chapter 37, Business ethics in Africa; Chapter 38, Business ethics in Latin America; and Chapter 39, Business ethics in transition: communism to commerce in Central Europe and Russia.

Notes

1 Such reflection may be done by business actors themselves (the focus of Niskanen’s argument), but it is also what the scholarly literature on business ethics does. Green and Donovan (2010: 22) explain that this literature not only seeks to understand the ethics of business actors and organisations, but also aims to improve “the quality of business managers’ ethical thinking and performance.”

p.373

2 Broadly speaking, the term “regulation” refers to one actor’s intervention in, or steering of, the activities of another actor. Such interventions may be based on rules (e.g., product standards) or take the form of incentives (e.g., environmental taxes); they may be carried out by governments or by private-sector actors; and they may be directed at activities in the private or the public sector. Yet, looking at the actual usage of the concept in the social sciences, scholars tend to refer to something more specific: regulation is primarily used to refer to forms of intervention that are carried out by government agencies over economic activities—in short, government regulation of business (Koop and Lodge 2017). It is also this meaning that we have in mind here. Business regulation, in this chapter, may be rule-based or incentive-based. When it comes to the term “businesses,” we primarily think of privately owned for-profit firms.

3 Not all economists working with the profit maximization assumption believe that it provides an accurate description of firms’ behavior; some solely believe that it is appropriate to use the assumption for the reason that, in the long run, only profit-making firms survive (e.g., Alchian 1950). This is also reflected in Friedman’s as if logic (1953: pt. 1): Firms may not actively seek to maximize profit, but as those firms that survive are the ones that attained the highest profits, we can model firms as if they aim at profit maximization. Interestingly, Kaneda and Matsui (2003) find that firms with profit maximization objectives are not the ones whose realized profits are largest. The authors conclude that the as if logic and the managerial theory are, in fact, compatible.

4 As set out in the introduction, Friedman adds that such profit maximization should conform to the “basic rules of society” (1970: 33). Such conformity does not go far beyond compliance with the law, even though deception is rejected, even if legal. A different conclusion on deception is drawn by authors such as Albert Carr (1968). For Carr, bluffing and other legal forms of deception are part of the business game. As in a poker game, bluffing does not reflect on the personal morality of the bluffer.

5 Peter Jaworski (2013) points to the importance of taking government failure into consideration in the business ethics literature. Though not a representative of the position described here, Jaworski argues that analysing government failure “will help us to turn our critical gaze on government actors and the role they play in generating socially non-optimal outcomes” (2013: 5).

References

Alchian, A.A. (1950). “Uncertainty, Evolution, and Economic Theory,” Journal of Political Economy 58:3, 211–221.

Alves, A.A. and J. Meadowcroft (2014). “Hayek’s Slippery Slope, the Stability of the Mixed Economy and the Dynamics of Rent-Seeking,” Political Studies 62:4, 843–861.

Ayres, I. and J. Braithwaite (1992). Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate. New York, NY, and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baldwin, R., M. Cave and M. Lodge (2012). Understanding Regulation: Theory, Strategy, and Practice, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bator, F.M. (1958). “The Anatomy of Market Failure,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 72:3, 351–379.

Baumol, W.J. (1962). “On the Theory of Expansion of the Firm,” American Economic Review 52:5, 1078–1087.

Boatright, J.R. (2009). “Rent Seeking in a Market with Morality: Solving a Puzzle about Corporate Social Responsibility,” Journal of Business Ethics 88:S4, 541–552.

Bowie, N.E. (1999). Business Ethics: A Kantian Perspective. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Brenkert, G.G. and T.L. Beauchamp (2010). “Introduction,” in Brenkert and Beauchamp (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 3–18.

Brennan, G. and J.M. Buchanan (1980). The Power to Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brennan, J. (2016). “Morality, Competition, and the Firm: The Market Failures Approach to Business Ethics by Joseph Heath (review),” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 26:1, E1–E4.

Buchanan, J.M. (1980). “Rent Seeking and Profit Seeking,” in James M. Buchanan, Robert D. Tollison and Gordon Tullock (eds), Toward a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 3–15.

Buchanan, J.M. (1996). “Distributional Politics and Constitutional Design,” in Vitantonio Muscatelli (ed.), Economic and Political Institutions in Economic Policy. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 70–78.

Buchanan, J.M. and R.D. Congleton (1998). Politics by Principle, Not Interest: Towards Nondiscriminatory Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

p.374

Carr, A.Z. (1968). “Is Business Bluffing Ethical?” Harvard Business Review 46:1, 143–153.

Carroll, A.B. (1989). Business and Society: Ethics and Stakeholder Management. Cincinnati, OH: South-Western.

Clark J.R. and D.R. Lee (2006). “Expressive Voting: How Special Interests Enlist their Victims as Political Allies,” in G. Eusepi and A. Hamlin (eds), Beyond Conventional Economics: The Limits of Rational Behaviour in Political Decision Making. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 17–32.

DeBow, M.E. (1992). “The Ethics of Rent Seeking? A New Perspective on Corporate Social Responsibility,” Journal of Law and Commerce 12:1, 1–21.

DeGeorge, R.T. (2010). Business Ethics, 7th edition. Prentice Hall, NJ: Pearson.

DiMaggio, P.J. and W.W. Powell (1983). “The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields,” American Sociological Review 48:2, 147–160.

Donaldson, T. and L.E. Preston (1995). “The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications,” Academy of Management Review 20:1, 65–91.

Evan, W.M. and R.E. Freeman (1988). “A Stakeholder Theory of the Modern Corporation: Kantian Capitalism,” in T. Beauchamp and N. Bowie (eds), Ethical Theory and Business, 2nd edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 75–93.

Fang, H. (2002). “Lottery versus All-Pay Auction Models of Lobbying,” Public Choice 112:3–4, 351–371.

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. Boston, MA: Pitman.

Friedman, M. (1953). Essays in Positive Economics. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and Freedom. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Friedman, M. (1970). “The Social Responsibility of Business Is To Increase Its Profits,” The New York Times Magazine, September 13.

Green, R.M. and A. Donovan (2010). “The Methods of Business Ethics,” In G.G. Brenkert and T.L. Beauchamp (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Business Ethics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 21–45.

Harberger, A.C. (1954). “Monopoly and Resource Allocation,” American Economic Review, 44:2, 77–87.

Harberger, A.C. (1959). “Using the Resources at Hand More Effectively,” American Economic Review 49:2, 134–146.

Hayek, F.A. (1944). The Road to Serfdom. London: Routledge.

Hayek, F.A. (1945). “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” American Economic Review 35:4, 519–530.

Heath, J. (2014). Morality, Competition, and the Firm: The Market Failures Approach to Business Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jaworski, P.M. (2013). “Moving Beyond Market Failure: When the Failure is Government’s,” Business Ethics Journal Review 1:1, 1–6.

Jaworski, P.M. (2014). “An Absurd Tax on our Fellow Citizens: The Ethics of Rent Seeking in the Market Failures (or Self-Regulation Approach),” Journal of Business Ethics 121:3, 467–476.

Jensen, M.C. (2002). “Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and the Corporate Objective Function,” Business Ethics Quarterly 12:2, 235–256.

Jensen, M.C. and W.H. Meckling (1976). “Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure,” Journal of Financial Economics 3:4, 305–360.

Jones, T.M. (1995). “Instrumental Stakeholder Theory: A Synthesis of Ethics and Economics,” Academy of Management Review 20:2, 404–437.

Kagan, R.A. and J.T. Scholz (1980). “The ‘Criminology of the Corporation’ and Regulatory Enforcement Strategies,” in E. Blankenburg and K. Lenk (eds), Organisation und Recht: Organisatorische Bedingungen des Gesetzesvollzugs. Jahrbuch für Rechtssoziologie und Rechtstheorie VII. Opladen, Germany: Westdeutscher Verlag, 352–377.

Kaneda, M. and A. Matsui (2003). “Do Profit Maximizers Maximize Profit? Divergence of Objective and Result in Oligopoly.” Available at: http://www.amatsui.e.u-tokyo.ac.jp/profit50.pdf.

Koop, C. and M. Lodge (2017). “What is Regulation? An Interdisciplinary Concept Analysis,” Regulation & Governance 11:1, 95–108.

Krueger, A.O. (1974). “The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society,” American Economic Review 64:3, 291–303.

Majone, G. (1994). “The Rise of the Regulatory State in Europe,” West European Politics 17:3, 77–101.

March, J.G. and J.P. Olsen (2008). “The Logic of Appropriateness,” in R.E. Goodin, M. Moran and M. Rein (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 698–708.

Meyer, J.W. and B. Rowan (1977). “Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony,” American Journal of Sociology 83:2, 340–363.

p.375

Mitchell, W.C. (1990). “Interest Groups: Economic Perspectives and Contributions,” Journal of Theoretical Politics 2:1, 85–108.

Murphy, K.M., A. Shleifer and R.W. Vishny (1993). “Why Is Rent-Seeking So Costly to Growth?” American Economic Review 83:2, 409–414.

Néron, P. and W. Norman (2008). “Citizenship, Inc.: Do We Really Want Businesses to Be Good Corporate Citizens?” Business Ethics Quarterly 18:1, 1–26.

Norman, W. (2011). “Business Ethics as Self-Regulation: Why Principles That Ground Regulations Should Be Used to Ground Beyond-Compliance Norms as Well,” Journal of Business Ethics 102:S1, 43–57.

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Olson, M. (1982). The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation and Social Rigidities. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Parker, C. (2013). “Twenty Years of Responsive Regulation: An Appreciation and Appraisal,” Regulation & Governance 7:1, 2–13.

Peltzman, S. (1976). “Towards a More General Theory of Regulation,” Journal of Law and Economics 19:2, 211–240.

Perry, J.L. and L.R. Wise (1990). “The Motivational Bases of Public Service,” Public Administration Review 50:3, 367–373.

Phillips, R.A. (1997). “Stakeholder Theory and a Principle of Fairness,” Business Ethics Quarterly 7:1, 51–66.

Risse, T. (2000). “‘Let’s Argue!’ Communicative Action in World Politics,” International Organization 54:1, 1–39.

Rodríguez, F. (2004). “Inequality, Redistribution and Rent-Seeking,” Economics and Politics 16:3, 287–320.

Simison, R.L. (1980). “Ford Fires an Economist,” Wall Street Journal, July 30, p. 18.

Smith, A. (1981) [1776]. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, R.H. Campbell, A.S. Skinner, and W. B. Todd (eds), 2 vols. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Stigler, G.J. (1971). “The Theory of Economic Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2:1, 3–21.

Suchman, M.C. (1995). “Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches,” Academy of Management Review 20:3, 571–610.

Tollison, R.D. (1982). “Rent Seeking: A Survey,” Kyklos 35:4, 575–602.

Tullock, G. (1967). “Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies and Theft,” Western Economic Journal 5:3, 224–232.

Tullock, G. (1971). “The Cost of Transfers,” Kyklos 24:4, 629–643.

Werhane, P.H. (2012). “Norman Bowie’s Kingdom of Worldly Satisficers,” In D.G. Arnold and J.D. Harris (eds), Kantian Business Ethics: Critical Perspectives. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 48–57.

Williamson, O.E. (1963). “Managerial Discretion and Business Behavior,” American Economic Review 53:5, 1032–1057.

Zak, P.J. (ed.) (2008). Moral Markets: The Critical Role of Values in the Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.