Chapter 9

Combat Games

Games seem to be everywhere nowadays. They aren't just for playing on the field or to be watched on the television. Games are in our homes, on our computers, and on our phones. They are with us everywhere. Why the fascination? Why play games? The first and I hope most obvious answer is that games are fun. Or at least they should be fun. But why talk about games in the context of violence for stage and film? Is not everything pre-planned and choreographed much like the lines that the performers say? In this way fight choreography is not dissimilar to learning the lines of the script. The performer knows what words to say and what movements to do weeks before a performance. Hopefully he or she has practiced and rehearsed these exact words and movements many times. However, particularly in the case of live theatre, sometimes things do not go as planned. The rehearsed words or moves do not happen as intended. Most performers have the training to cover or improvise when this happens with words. But what about when it happens with fight choreography? If the performers are only versed in the exact moves of the altercation and not necessarily the concepts behind them, any interruption to the flow of the choreography will most likely grind to a halt. There will be no improvising because the performers do not have the training or the skill to adjust. This grinds not only the fight but also the entire production to a halt. This cannot happen. The show, as someone once famously said, must go on.

Developing and playing games, particularly ones that build skills and reinforce concepts tied to the art of acting and theatrical violence, enables the performer to adapt to real-time situations in performance. This allows the performer to be more in the moment and truly sensitive to the action rather than re-enacting a pre-determined sequence of moves. There is no doubt that learning choreography, a set pattern of physical moves, is a skill that any performer must acquire with proficiency. But this cannot be the sole purpose of presenting violence on stage. It has no soul, no possibility, nothing beyond simply choreography. There must be something more for the actor. Games allow the actor to make connections, both physical and conceptual, between executing choreography and bringing that choreography to life in performance.

The following games are for two people. I will refer to these people as "players" because that is what they should be doing with each other. Playing. The intention of each game will switch between competitive and cooperative but the essence of play should stay intact throughout.

Push and Release

The first time I remember playing this game was at the University of Toowoomba in Queensland, Australia. It was in a class taught by Tony Wolf for the Paddy Crean Workshop organized by the International Order of the Sword and Pen. It is also one of the first games I introduce to a group of actors when trying to get to know what their habitual patterns of movement are. It also provides a window into a person's attitude towards combative or competitive physical interactions with another person.

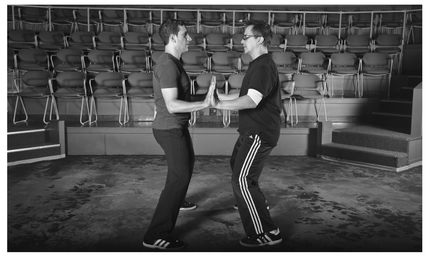

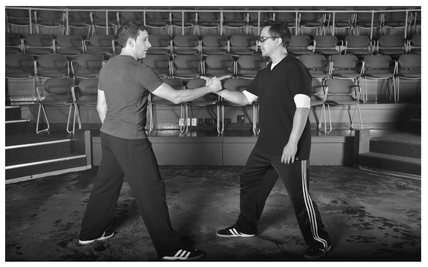

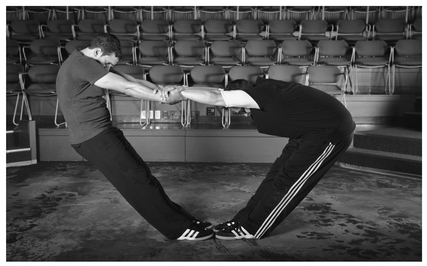

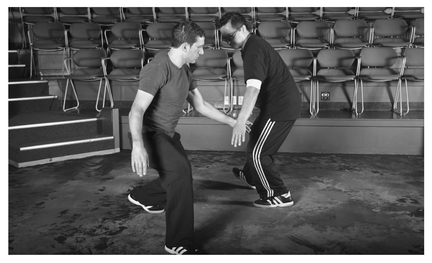

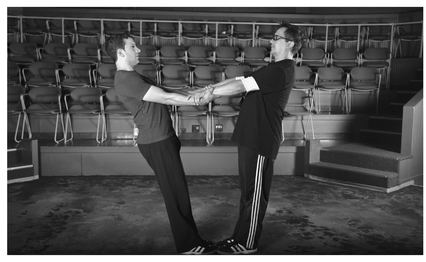

Both players start by facing each other in a neutral stance. The feet should be parallel to each other and at least shoulder-width apart with the knees bent. Players with dance training might think of this initial position as second position in deep plié. Players with a martial arts background could assume a horse stance or riding stance. The players get close enough to each other so that each player can touch the palms of the other. The arms of each player should be bent and not outstretched. The beginning of this game is cooperative. Both players play with sharing weight only through the contact in the palms (Figure 9.1). The feet should remain in place. Players should feel free to explore their shared mobility through the arms, torso, hips, and knees as they move in response to each other. This is also a nice way to gently warm up the muscles and joints and also make contact with another player.

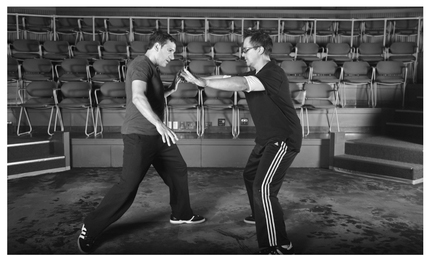

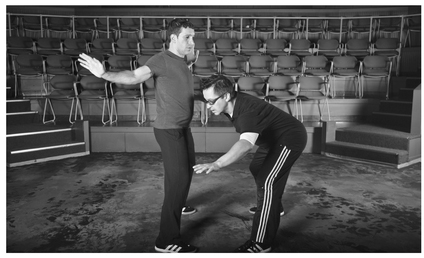

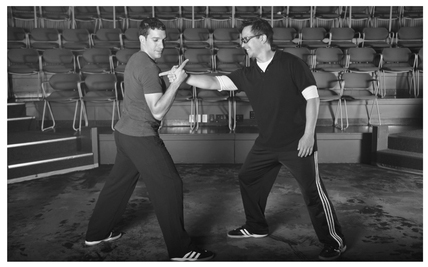

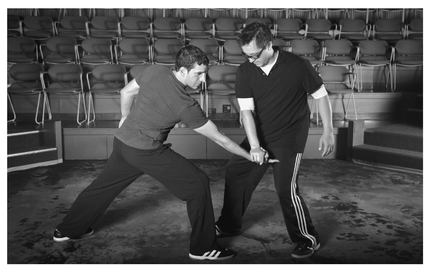

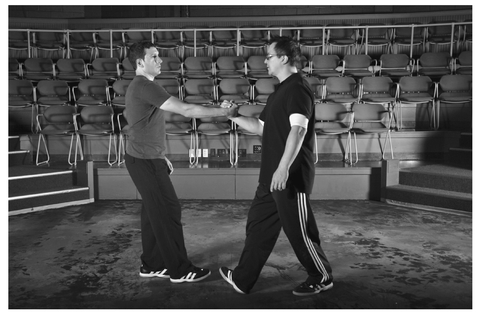

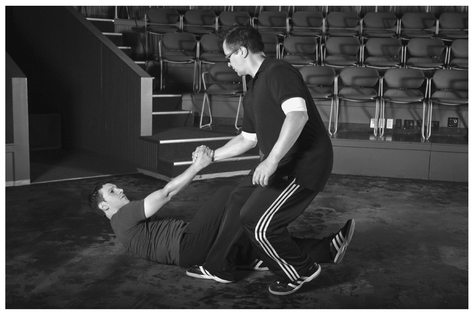

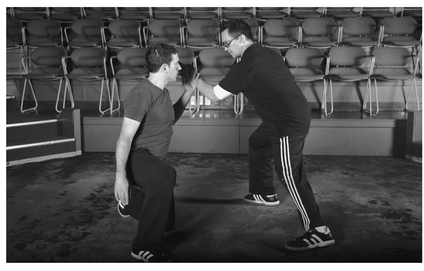

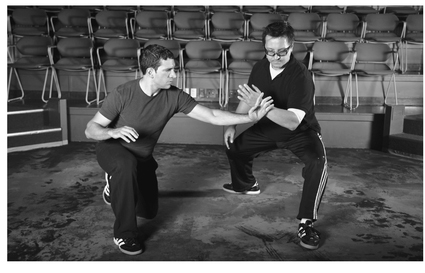

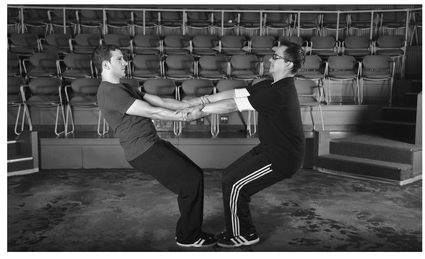

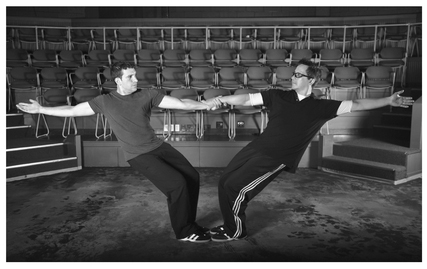

Then, at a mutually and verbally agreed upon moment, the game becomes competitive. The goal of this game is to create an imbalance in the other player so that one or both feet move from their initial starting position without losing one's own balance. This can only be accomplished through the player connectivity in the palms. A player may choose to push through the palms of the other player to create this imbalance (Figure 9.2). If, however, one player elects to push and the other player senses the push, the second player may release the contact in an attempt to get the first player off-balance (Figure 9.3). As a result there are two ways to be successful and win at the game – Push or Release. Exactly when a player elects to use either tactic is entirely up to him or her. Keep in mind that if a player releases the contact between player palms and no one is off balance, the contact is immediately initiated once again. A running tally is kept during the course of the game to see how many times one player can get the other player off-balance. If a player bends over Matrix-style but maintains his or her foot position then no point is scored.

After the first round, ask yourself the question, "What technique was most successful for me? Push or release?" Ask the other players in the group the same. There will be some people who find that pushing yields better results for them. Others will notice that they tried to find more opportunities for releasing and letting the energy of their partners carry them off balance. It's a binary situation. Nearly 95% of people fall into one of the two camps. Perhaps 5% of players will use the techniques of pushing and releasing equally but these are rare. The first thing to do is notice what your natural default mode is for playing a competitive or combative game with someone. Do you like to push or release? Do you like to make the first move or do you prefer to respond to what someone else does first? Do you like sending energy out and away from you into another body or so you prefer to receive energy and turn it to your advantage? There is no one way better than another. Ask yourself these questions honestly and answer them without judgment.

Typically I find in a group of actors there are more release players than push players. Actors, particularly ones who have elected to take classes to further their training, have cultivated the ability to respond very well to situations. They tend to defer to the wishes of others whether that is the instructor, a new scene partner, a fellow classmate, or a director. They are good at taking direction. It doesn't matter where the direction comes from, or if it's physical or conceptual. Actors have developed this ability to negotiate the business of performing. It shows up even in the classroom setting. This is not something that should be judged or criticized but it should be recognized because it leads to physical tendencies in the body that should be acknowledged.

Once you have identified your tendency play the game again with the same partner and see if you can find opportunities to be successful at the game by making the choice you didn't habitually default to in the first round. If you are a Push person, find opportunities to release. If you are a Release person, look for places to push. This doesn't mean the players don't still use the tactics that worked for each of them initially. Each player simply tries to utilize his or her respective non-habitual choice to make the game more unpredictable.

Once you have played round two trying to make the non-habitual choice with the same partner change partners if you can. Go immediately into the competitive version of Push and Release. The next person you meet may be smaller than you, or taller, or have longer arms, or stronger legs than you. Whether you are conscious of it or not you will be sizing up your opponent to see what tactics you will use to win at the game. You will probably wonder from the other player's physical stature and build if he or she is a Push person or a Release person. But how do you really know? You won't know unless you play with them. By playing the game a player gets to know the tendencies, patterns, and behavior of the other player. And the more you play the game with different players the more you will get to know your own tendencies, patterns, and behavior when put in this particular situation. The act of playing the game allows the players to find out about themselves and about each other. When you and I play, I start to know more about myself because you start to know more about yourself. We help each other know.

There are of course some pitfalls. Some players will be reluctant to play the game fully and to win. This will be manifested in a few ways. When they are trying to push they will indicate this to their partner by leaning in and shifting their centers forward in front of their point of balance. A receptive opponent will pick up on this and simply release. Some less observant players may just lean-push back creating a stalemate. The game becomes boring when force meets force over and over. This would be the equivalent of a scene where two characters shout at each other over and over. The actors feel like they are expending a lot of energy but the situation goes nowhere.

Another form of indicating is when a player prepares to push. The shoulders rising up and the hands actually moving back towards the player doing the push before extending to the opponent whom the player is trying to push off-balance exhibit this. This going back-to-go-forward motion is not rooted in a desire to play the game but be "nice" to the other player by announcing the intent to push. Again, observant opponents will simply release and score a point by letting the pusher put themselves off-balance. Of course this is a severe handicap to the player preparing to push. It is also very boring to play against or even watch this player because we know what the player is going to do before he or she does it. That's not very exciting is it? The best players don't prepare to push or release. They simply do the action. This makes the game more impulsive, surprising, and more interesting to play and watch.

The goal of the game is to get the opponent off-balance. The way a human body becomes off-balance is when the center of gravity goes beyond the equilibrium point provided by the orientation of the feet. You may notice that when some players push they stop their push a few inches in front of the space where the body of their opponent is. This also becomes a handicap to the player pushing. The full effect of the push cannot be realized unless the arms of the player initiating the push are fully extended past the center of the opponent. Stopping short results in, at best, a tickle and not a push. Another form of the not-push is when the direction of the push does not travel through the palms directly towards the body of the opponent. Rather you may see the push flaring out to the sides as if the player doing the push is waving the air away that surrounds the opponent. If we truly want to win at the game, we would attempt to initiate a change in the balance of the other player by affecting the positive space of their body rather than the negative space around it.

A typical game lasts 3 minutes. Shorter games can be played but I find that the longer games allow for more opportunities for strategy and deep physical listening.

Finger Fencing

Finger fencing is a great game I also first learned from Tony Wolf, and then was reintroduced to when studying fencing at Bay State Fencers in Somerville, MA. While this game may seem more suited as training for swordplay it actually has more applications for tactile kinesthetic response, since the game is played through constant contact.

9.5

The players take either their right or left hands (a matter of preference) and clasp them in what I call the "buddy clasp." It's not a handshake position where the thumbs are on top but rather a clasping of the hands where the fingers are on top. This should put the hands in a position to extend the index fingers straight out so that they point to the other player (Figure 9.4). I suggest accompanying the extension of the index finger with a sound effect to signal a strong start to the game. I find "SHING!" works quite nicely. The players stay connected through the duration of the game. The goal is to score a touch on the other player's body without being scored on (Figures 9.6-9.7). The entire body is fair game excluding sensitive areas and the face for what I hope are obvious reasons. Players should move each other around to take advantage of angles and positioning to score a touch. Each game should be played for 2 minutes. I think you'll find that 2 minutes is more than enough to work up a good sweat.

This is a competitive game where the score is continually tallied through the 2 minutes. Initially new players will most likely simply try to overpower each other. As they fatigue and realize that it is nearly impossible to blast through the other's defenses, the players will naturally start to circle each other trying to look for opportunities and openings to score touches. This will bring awareness particularly to the lower half of the body where the legs become vulnerable targets. As more attempts are made to score on the legs, this will oblige each player to be more agile with their feet, moving not only the individual, but also the other player through the space more vigorously through the course of the game.

Players will find that if they are really trying to score a touch and really trying not to be touched then both players will range about the playing space quite a bit. It also brings spatial awareness of the players as a unit to the fore. Playing this game in a group is even more challenging because all of the couples must play the game and play to win without crashing into other couples. Later on, when mass battles, rumbles, and bar fights are studied, this is a good introduction to group awareness in a violent, combative context.

Weight Share: The Shape of Conflict

There are two weight share games that I enjoy very much and are simple ways to initiate contact with a partner. They are great games to reinforce trust and kinesthetic response at a slower tempo.

I played this game for the first time at summer camp. The two players stand back to back. The goal is for both to lower themselves to the ground slowly by leaning into each other without using their hands or speaking. The final position is typically the two players sitting back to back with their knees bent. I, however, enjoy sliding the hips out at this point more and more, again without the use of the hands, until both players are lying supine or face up with their heads resting side by side on each other's shoulder. The players should then attempt to get back up in the same manner, leaning into each other without speaking. In order to get back to the seated position, the hands may be used. But getting from the seated position to standing should require no hands at all. If you are wearing socks you may find this difficult as the feet will tend to slip out from underneath the more you lean into your partner.

It is a classic cooperative weight share where both players must work together wordlessly to move in a controlled manner without crashing back to the ground. The secret lies in the amount of weight one gives the other person. Give too much and your partner gets overwhelmed and crunched into the fetal position. Give too little and you get overwhelmed yourself. The players must find the perfect combination of force and weight to put into each other. The more surface area connection each player feels along the back the more likely they will be relying on each other to keep from crashing down. Just the right amount of force each way will result in both bodies moving steadily towards the floor or away from it.

Another variation of this weight share I played many times in acting school, mostly in my movement classes. In this variation both players face each other and stand toe to toe.

9.9

9.10

9.12

The players grasp each other gently, one right hand to the partner's left forearm and the left hand to the partner's right forearm. Very slowly the partners lean back and extend their arms. Eventually, both players' arms should be straight with only the slightest necessary muscular tension present to keep holding on to the other person. The players should feel as though if either person let go then both would fall to the floor (Figures 9.8-9.11).

Even though the games are cooperative by nature one could easily see how these shapes could be used in a violent interaction. In the first game two bodies are pushing into each other, In the non-cooperative version of this we might imagine that one person is trying to dislodge another from a location or position in order to gain a dominant advantage. In the second game the two bodies are pulling at each other. Here we may imagine a competitive interaction where one person is trying to make another person move to a certain point. In either event, it is a moment of possibility where something is on the verge of change. If you look closely, notice what kind of shape is made during each of these weight-share exercises. The size of the shape changes but it is always there in one form or another. The easiest way to see it is during the second exercise, face-to-face, with the arms outstretched and relaxed. If the players' bodies are of a similar size you will find a perfect equilateral triangle. Look for the triangle again in the other exercises, or when the position of the bodies changes throughout the exercise. The type, location, or number of each triangle might change but the triangle will always be present.

Triangles are the structure of change, or heat, of motion. In science and mathematics the symbol "delta" is a triangle and signifies change. In chemistry a compound structure that is triangular in shape is nearly always transitional and is always looking to transition to a more stable structure. We can see this in human bodies. Two football players on the gridiron run towards each other. Their upper bodies press forward and gather momentum. At the moment of impact a triangle is made, each body leaning into the other on impact.

Performers should be sensitive to whether or not they are making the correct shapes on stage to represent the violence. If the actors' bodies are fully upright and parallel to each other a square or rectangle exists between them. Even if they hurl invectives at each other there will be little threat of violence unless the space between them changes. A triangle must be created. If none exists the audience will perceive that there is no real conflict between the characters. The sides must either collapse or expand for the interaction to go anywhere.

Drunken Sailors

This is a cooperative game that combines elements of the previous weight sharing exercise as well as the finger fencing game. Both partners should begin in the same "buddy clasp" position as in finger fencing (Figure 9.13). The partners should decide who is going to move forward first and who will move backward. The partner moving forward should follow the lead of the partner moving backward (Figure 9.14). The partner moving back should walk slowly at first and use the counter-balance of the partner moving forward to gently move to the ground in the supine position (Figure 9.15). When done properly and with balanced control the partner going to the ground should not have to use the other hand to touch the floor, hi fact, this game should develop a habit of not having to use the hands at all when descending to the floor. Once one partner is lying on the ground, the other partner now begins to walk backward helping the first partner up off the floor. The partner now walking backward is leading the motion and continues to walk back until the other partner is up and walking forward. Now the exercise is repeated for the other partner. As the game continues the partners may wish to increase their tempo. As the tempo increases the partners should begin making sounds as though they were intoxicated sailors on a boat that is listing side to side. If the game is going really well the partners may elect to change the directions after each turn. This game will start to develop the physical and vocal actions involved in the techniques where the performers go to the ground.

Pushing Hands

This is a game that follows from an exercise I first learned when studying Long Fist and White Crane Gongfu and Tai Chi at YMAA with Dr. Yang, Jwing-Ming. The traditional exercise is used for students to experientially investigate principles used in martial arts such as timing, centering, coordination, and sensitivity. Different schools may have their own flavor of how to conduct the pushing hands exercise. The following is just one suggestion of a sequence to an activity that I have found incredibly useful in physical training for the performer.

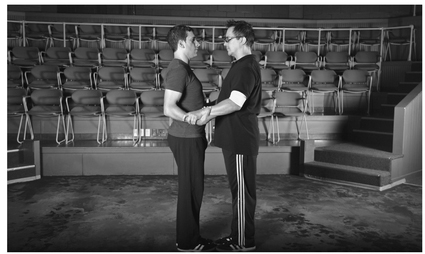

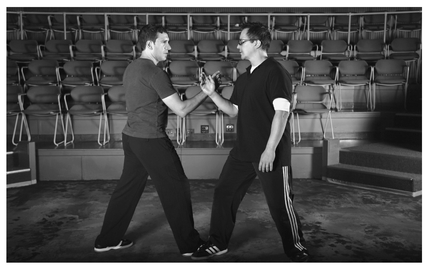

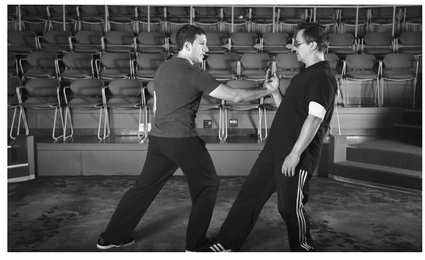

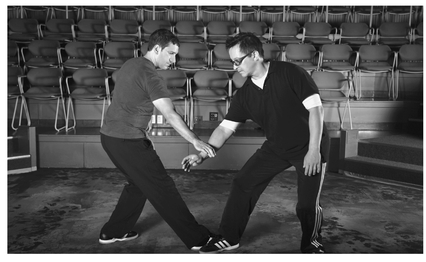

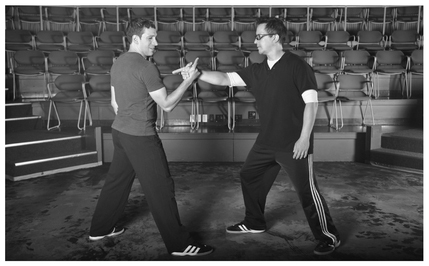

Essentially this version of pushing hands is a game of leading and following. It is a cooperative game where both players strive for a deeper, more significant physical interaction rather than one player simply trying to keep up with the other. Both players start the game in a closed stance; both right foot forward or left foot forward. The outside of each player's lead foot should be flush up against the other player's lead foot. Whichever side or foot is forward, raise the corresponding lead arm so that the back of one player's lead forearm or wrist contacts the back of the wrist or forearm of the other player (Figure 9.16). It is decided verbally between the two players who will lead and who will follow. The objective of the game is simply to maintain the contact between the arms at all times. The leader will begin by simply and slowly moving his or her arm in any direction he or she chooses without displacing the feet. The follower will simply follow the movements dictated by the leader (Figure 9.17). Both players are responsible for maintaining the contact. Try to experiment with moving in as many directions in space as is possible with your partner without losing the contact. If the contact is disrupted at any time the players should reset from the initial starting position and begin the game again (Figures 9.18-9.19).

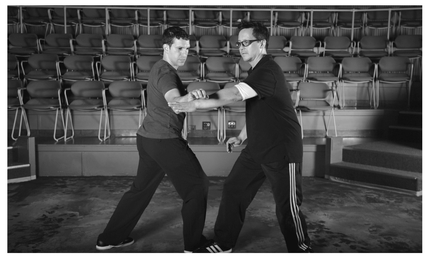

After some time the follower may be tired of following. At any time the person who is following can take leadership of the interaction by giving a clear physical motion with the arm that is not already in contact with the partner. The follower should sweep the arm in a wide, arcing fashion intercepting the partner's arm that is already in contact with the player (Figure 9.20). Again, there should be no moment when the players are ever not in physical contact with each other. As a result, the moment of interception will actually have three arms in contact before the follower takes the arm that has already been more active in the exercise away. Once the exchange has been made then whoever was following is now leading and whoever was leading is now following. Changes of leadership can happen at any time.

Some things to consider: try to let the movement start at a slower pace and then build in tempo as the interaction between the players deepens. If the contact is lost, then you know you have gone too fast for the interaction and the players should begin the game again in the initial starting position at their slowest shared pace.

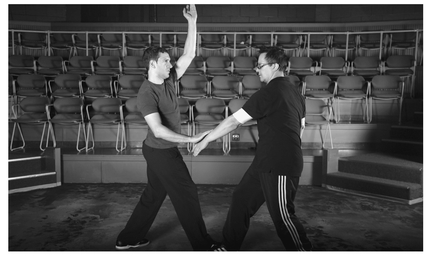

Once a good connectivity has been established, one player who is leading may elect to start moving his or her feet so that both bodies now become mobile (Figure 9.21). By utilizing the topography and dimensions of the space with the now mobile unit, the two players can more freely explore the horizontal extension and vertical level possibilities of their shared physical system. They can see how high they can reach to the ceiling together or how their bodies interact on the floor (Figures 9.22-9.23). Anything is possible as long as the physical point of contact remains constant.

Something to consider: do you like leading or following or both equally? Most actors I meet enjoy following much more than leading. Whatever your preference play the game again, except this time look for more opportunities to engage with the part of the game you don't gravitate towards as much. If you like to lead, try following longer. If you like to follow, try to take the lead more often. See if and how this changes the game and your interaction with your partner. Regardless, remember what your proclivity is. It is good information to know what role of leading or following we typically default to.

Ocular Focus (Aka Eye-Contact)

Once the players have played this game for a few minutes they should now draw their attention to their focus. Where were they looking? Typically when people new to Pushing Hands play in this way, they keep their eyes on the point of contact, in this case the wrists or forearms. This makes sense as a person will use sight to get extra information about the point of contact and its location in space in relation to his or her partner. But we already have the sense of touch giving us information through the physical contact. Do the players need to rely so heavily on looking at the point of contact to actually respond to each other?

Try the exact same exercise keeping all of the guidelines listed above. The only difference this time is the players should start the game by looking anywhere but the point of contact. The players can look at the fan on the ceiling or a speck of dust on the floor or the knee of the other partner – anywhere but the point of contact at the wrist. Players should make sure that they have a specific and exact point of focus.

There can be a tendency in this part of the exercise to shift into "soft-focus" where the eyes are not looking anywhere or focusing on anything in particular. Peripheral vision is an important ability to acknowledge. However, relying too much on this ability makes one's focus too general. By being in a constant state of soft-focus one ends up focusing on everything. And when one focuses on everything it is really a focus on nothing since all things in the world, or at least one's view, cannot and should not all have the same value. This is particularly true for performers on stage. We are in the business of showing an audience what is important and to do that we must make choices. The most basic of these choices is where to look and what to look at. If you look at something with interest then the audience will tend to follow suit. Peripheral vision and soft focus are useful. They open up our awareness to the things around us so that we can then shift focus when necessary. This should naturally happen in this variation of the game. The point of focus can shift as long as it never rests on the point of contact. Experiment with the distance you look away from your partner as well as the duration of time you look away. Try to experiment with extremes of both great and small distances from your partner and long and short time duration in settling on a point of focus.

For the next variation of this game begin again at the starting position. Keep the same guidelines but change the ocular focus yet again. Now the players should look into each other's eyes, holding eye contact for the duration of this next play. The eye contact should be fixed and never waver from the eyes. If the eyes of one player flit back to the wrist or down to the feet at any given time, the other player should immediately insist that the eye contact be re-established. One way to do this is for the follower to take over leadership immediately if the leader breaks eye contact. If the follower breaks eye contact then the leader can adjust his or her level to get right in front of the follower's eyes wherever they happen to wander. Yet another way is for one player to tell the other player who looks away, "Don't look away from me!" The players should feel free to turn it into a staring contest.

Typically players feel that the game shifts considerably when eye focus is changed, particularly when the focus is locked on the eyes. Notice how each change in focus changes your attitude towards your partner, the exercise, and the way in which you move.

Seeing without Seeing

Now that the game has been played for a bit and if you and your partner are feeling comfortable in the rhythm and connectivity you have established you may be ready for the following variation. All of the guidelines are in place once again with regard to staying in constant contact, change of leadership, exploring levels, space, tempo, etc. The players begin at the starting position. This time both players close their eyes. It should go without saying that even if you feel a good connection with your partner, please start this variation of the game slowly and far away from any sharp objects or high cliffs. Do, however, try to do this in a space where other players are playing the same game. This aspect of the game can be the most frightening and exhausting but also the most fun. The other senses of the body become ultra-sensitive when sight is deprived and the body is in motion. Be sure the pace with your partner is manageable, take sure steps, and use the off-hand that is not connected to your partner as a "whisker" to feel the space around you and avoid possible collisions with tables, walls, or other people.

If having both partners without sight proves too much too soon, the game can also be played where only one partner closes his or her eyes. Try this exercise in both ways where the leader has his or her eyes open and the follower has his or her eyes closed or vice versa to experience the different effects sightlessness has on leading and following.

Now that you have experienced each version of Pushing Hands you can shift freely using all of the variations you have explored so far in a single play. Partners should keep exploring and experimenting with physicality through constant contact while also shifting through all of the possibilities for ocular focus. Note that each partner can choose what to focus on individually in his or her own time. One partner may be focusing on the point of contact while the other partner is focusing on the chair across the room. Or one partner may be focusing his or her eyes on the other partner while that partner has his or her eyes closed. Feel free to play with as many variations as possible but never lose the specificity of ocular focus.