C H A P T E R 26

Taking Control of the System

By now, you should be starting to realize that the shell offers an enormous amount of power when it comes to administering your PC. The BASH shell commands give you quick and efficient control over most aspects of your Linux setup. However, the shell truly excels in one area: controlling the processes on your system.

If you are only running a home computer, you may not have to pay much attention to processes. However, if you are running a shared machine or a network, controlling processes can be essential for administration of your system. You can tidy up crashed programs, for example, or even alter the priority of a program so that it runs with a little more consideration for other programs. Unlike with Windows, this degree of control is not considered out of bounds. This is just one more example of how Linux provides complete access to its inner workings and puts you in control.

![]() Tip This chapter concentrates on using the Terminal to provide powerful control over your system. If you'd rather avoid working in the Terminal but would still like to view and control processes, you can do so in the Processes tab of the System Monitor program. Extra functions are available via the right-click context menu. This interface doesn't provide the advanced level of control that you can get from the shell, though.

Tip This chapter concentrates on using the Terminal to provide powerful control over your system. If you'd rather avoid working in the Terminal but would still like to view and control processes, you can do so in the Processes tab of the System Monitor program. Extra functions are available via the right-click context menu. This interface doesn't provide the advanced level of control that you can get from the shell, though.

Viewing Processes

A process is one instance of a software program, with its associated state. When the user runs a program one or many processes might be started, but they're usually invisible unless the user specifically chooses to manipulate them. You might say that programs exist in the world of the user, but processes belong in the world of the system.

Processes can be started not only by the user, but also by the system itself to undertake tasks such as system maintenance, or even to provide basic functionality, such as the GUI system. Many processes are started when the computer boots up and then they sit in the background, waiting until they're needed (such as programs that provide printing functionality). Other processes are designed to work periodically to accomplish certain tasks, such as ensuring that system files are up to date.

You can see the most active processes currently running on your computer by running the top program. For more advanced control, you can also see a complete list of all processes on your computer by using the ps aux command. Running top is easier, though, because top not only shows the most active processes, but also gives you some management options for them. Running top is simply a matter of typing the command at the shell prompt.

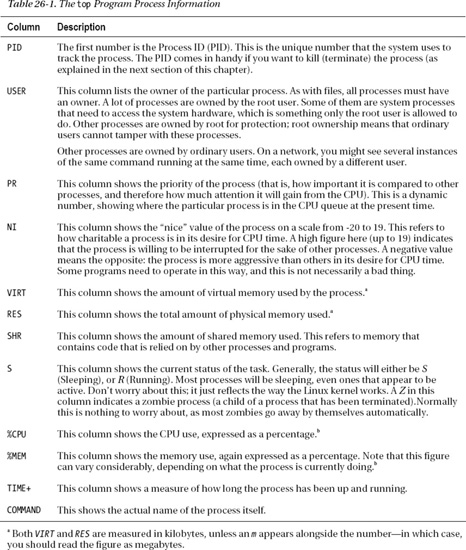

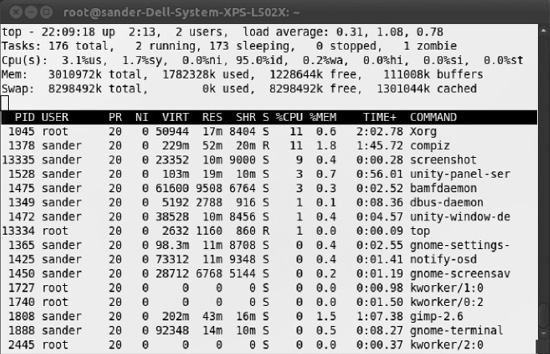

As you can see in Figure 26-1, top provides comprehensive information and can be a bit overwhelming at first sight. However, the main area of interest is the list of processes (which top calls tasks).

Figure 26-1. The top program gives you an eagle-eye view of the processes running on your system.

Here's an example of a line taken from top on our test PC, shown with the column headings from the process list:

PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND

5499 root 15 0 78052 25m 60m S 2.3 5.0 6:11.72 Xorg

A lot of information is presented here, as described in Table 26-1.

This list will probably be longer than the screen has space to display, so top orders the list of processes by the amount of CPU time the processes are using and you only see the most active of these processes. Every few seconds, it updates the list. You can test this quite easily. Open a Nautilus file-browsing window (Places ![]() Home) and then let your PC rest for a few seconds, without touching the mouse or typing. Then click an icon in the Nautilus window. You'll see that the process called

Home) and then let your PC rest for a few seconds, without touching the mouse or typing. Then click an icon in the Nautilus window. You'll see that the process called nautilus leaps to the top of the list (or appears very near the top).

Near the top of the list will probably be Xorg. This is the program that provides the graphical subsystem for Linux; making the mouse cursor appear to move around the screen and drawing program windows requires CPU time.

![]() Tip Typing d while

Tip Typing d while top is running lets you alter the update interval, which is the time between screen updates. The default is 3.0 seconds, but you can reduce that to 1 second or even less if you want (that is, a fraction of a second, such as 0.5). However, a constantly updating top program starts to consume system resources and can therefore skew the diagnostic results you're investigating. Also, it's virtually impossible to analyze the data that top shows if these data get updated every 0.5 seconds. Because of this, a longer, rather than shorter, interval is preferable.

It's possible to alter the ordering of the process list according to other criteria. For example, you can list the processes by the quantity of memory they're using, by typing M while top is up and running. You can switch back to CPU ordering by typing P.

To quit top, type q.

RENICING A PROCESS

Controlling Processes

Despite the fact that processes running on your computer are usually hidden away, Linux offers complete, unrestricted control over them. You can terminate processes, change their properties, and learn every item of information there is to know about them.

This provides ample scope for damaging the currently running system but, in spite of this, even standard users have complete control over processes that they personally started (one exception is zombie processes, described a bit later in this section). As you might expect, the root user (or any user who adopts superuser powers) has control over all processes that were created by ordinary users, as well as those processes started by the system itself.

The user is given this degree of control over processes in order to enact repairs when something goes wrong, such as when a program crashes and won't terminate cleanly. It's impossible for standard users to damage the currently running system by undertaking such work, although they can cause themselves a number of problems.

![]() Note This control over processes is what makes Linux so reliable. Because any user can delve into the workings of the kernel and terminate individual processes, crashed programs can be cleaned up with negligible impact on the rest of the system.

Note This control over processes is what makes Linux so reliable. Because any user can delve into the workings of the kernel and terminate individual processes, crashed programs can be cleaned up with negligible impact on the rest of the system.

Killing Processes

Whenever you quit a program or, in some cases, when it completes the task you've asked it to, it will terminate itself. This means ending its own process and also that of any other processes it created in order to run. The main process is called the parent, and the ones it creates are referred to as child processes.

![]() Tip You can see a nice hierarchical display of which parent owns which child process by typing pstree at the command-line shell. It's useful to add the

Tip You can see a nice hierarchical display of which parent owns which child process by typing pstree at the command-line shell. It's useful to add the -p command option (that is, pstree -p). This adds the PIDs to the output. It's worth piping this into the less command so you can scroll through it: type pstree | less. By using a pipe, you send the result of the first command through the pager less, which allows you to browse the results page by page.

Although this termination should mean that your system runs smoothly, badly behaved programs sometimes don't go away. They stick around in the process list. Alternatively, you might find that a program crashes and so isn't able to terminate itself. In rare cases, some programs that appear otherwise healthy might get carried away and start consuming a lot of system resources. You can tell when this happens because your system will start slowing down for no reason, as less and less memory and/or CPU time is available to run actual programs.

You can in some cases get rid of these troublesome processes by logging out then immediately logging back in. This works however, only for those processes that you've started after logging in to the computer and not for system processes. Another way to handle them is to kill the process and terminate it manually, with the advantage that this works for all processes and not just a small selection. This is easily done by using top.

The first task is to track down the crashed or otherwise problematic process. In top, look for a process that matches the name of the program, as shown in Figure 26-2. For example, the Mozilla Firefox web browser generally runs as a process called firefox-bin.

Figure 26-2. You can usually identify a program by its name in the process list.

![]() Caution You should be absolutely sure that you know the correct process before killing it. If you get it wrong, you could cause other programs to stop running.

Caution You should be absolutely sure that you know the correct process before killing it. If you get it wrong, you could cause other programs to stop running.

Because top doesn't show every single process on its screen, tracking down the trouble-causing process can be difficult. A handy tip is to make top show only the processes created by the user you're logged in under. This will remove the background processes started by root. You can do this within top by typing u and then entering your username.

After you've spotted the crashed process, make a note of its PID number, which will be at the very left of its entry in the list. Then type k. You'll be asked to enter the PID number. Enter that number and then press Enter once again (this will accept the default signal value of 15, which tells the program to terminate).

The process (and the program in question) should disappear. If it doesn't, there might be a good reason why you can't terminate the processes. Fortunately, there also is a method to force a process to terminate. Just repeat the same procedure as described previously, but now when top asks Kill PID … with signal ]15], don't press Enter to accept this default value, but enter the number 9 and press Enter. This will remove the process with force from your computer. Only do this for processes that you really need to go away, because a process that is terminated this way, won't close its resources nicely and you might lose data.

![]() Note No magic is involved in killing processes. All that happens is that

Note No magic is involved in killing processes. All that happens is that top sends them a “terminate” signal. In other words, it contacts them and asks them to terminate. By default, all processes are designed to listen for commands such as this; it's part and parcel of how programs work under Linux. When a program is described as crashed, it means that the user is unable to use the program itself to issue the terminate command (such as Quit). A crashed program might not be taking input, but its processes will probably still be running.

Controlling Zombie Processes

Zombie processes are those that are children of processes that are no longer reachable, for instance because they have terminated. However, for some reason, they failed to take their child processes with them. Zombie processes do occur occasionally.

Often, zombie processes are harmless. In some cases, they can cause confusion and may be the reason why restarting a process doesn't work. That's why you sometimes need to kill them yourself.

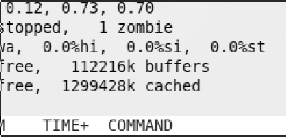

In the top-right area of top, you can see a display that shows how many zombie processes are running on your system, as shown in Figure 26-3. Zombie processes are easily identified because they have a Z in the status (S) column within top's process list. To kill a zombie process, type k and then type its PID. Then type 9, rather than accept the default signal of 15.

Figure 26-3. You can see at a glance how many zombie processes are on your system by looking at the top right of top's display.

In many cases, zombie processes go away by themselves, but in some cases, they don't. When this happens, you have two options. The first is to simply log out and log in again. Alternatively, you can reboot the computer.

Using Other Commands to Control Processes

You don't always need to use top to control processes. A range of quick and cheerful shell commands can diagnose and treat process problems.

The first of these is the ps command. This stands for process status and will report a list of currently running processes on your system. This command is typically used with the aux command options (there's no need to provide a dash before the options, as with most commands):

ps aux

This will return a list something like what you see when you run top. If you can spot the problematic process, look for its PID and issue the following command:

kill <PID number>

For example, to kill a process with a PID of 5122, you would type this:

kill 5122

If, after that, you find the process isn't killed, then you should use the top program, as described in the previous sections, because it allows for a more in-depth investigation.

Another handy process-killing command lets you use the actual process name. The killall command is handy if you already know from past experience what a program's process is called. For example, to kill the process called firefox-bin, which is the chief process of the Firefox web browser, you would use the following command:

killall firefox-bin

![]() Caution Make sure you're as specific as possible when using the

Caution Make sure you're as specific as possible when using the killall command. Issuing a command like killall bin will kill all processes that might have the word bin in their name!

CLEARING UP CRASHES

Controlling Jobs

Whenever you start a program at the shell, it's assigned a job number. Jobs are quite separate from processes and are designed primarily for users to understand what programs are currently doing on the system.

You can see which jobs are running at any one time by typing the following at the shell prompt:

jobs

When you run a program, it usually takes over the shell in some way and stops you from doing anything until it's finished what it's doing. However, it doesn't have to be this way. Adding an ampersand symbol (&) after the command will cause it to run in the background. This is not much use for commands that require user input, such as vim or top, but it can be handy for commands that churn away until they're completed.

For example, suppose that you want to decompress a large Zip file. For this, you can use the unzip command. As with Windows, decompressing large Zip files can take a lot of time, during which time the shell would effectively be unusable. However, you can type the following to retain use of the shell:

unzip myfile.zip &

When you do this, you'll see something similar to the following, although the four-digit number will be different:

[1] 7483

This tells you that unzip is running in the background and has been given job number 1. It also has been given process number 7483 (although bear in mind that when some programs start, they instantly kick off other processes and terminate the one they're currently running, so this won't necessarily be accurate).

![]() Tip If you've ever tried to run a GUI program from the shell, you might have realized that the shell is inaccessible while it's running. After you quit the GUI program, the control of the shell is returned to you. By specifying that the program should run in the background with the

Tip If you've ever tried to run a GUI program from the shell, you might have realized that the shell is inaccessible while it's running. After you quit the GUI program, the control of the shell is returned to you. By specifying that the program should run in the background with the & (ampersand symbol), you can run the GUI program and still be able to type away and run other commands.

You can send several jobs to the background, and each one will be given a different job number. In this case, when you want to switch to a running job, you can type its number. For example, the following command will switch you to the background job assigned the number 3:

%3

You can exit a job that is currently running by pressing Ctrl+Z. It will still be there in the background, but it won't be running (officially, it's said to be sleeping). To restart it, you can switch back to it, as just described. Alternatively, you can restart it but still keep it in the background. For example, to restart job 2 in the background, leaving the shell prompt free for you to enter other commands, type the following:

%2 &

You can bring the command in the background into the foreground by typing the following:

fg

When a background job has finished, something like the following will appear at the shell:

[1]+ Done unzip myfile.zip

Using jobs within the shell can be a good way of managing your workload. For example, you can move programs into the background temporarily while you get on with something else. If you're editing a file in vim, you can press Ctrl+Z to stop the program. It will remain in the background, and you'll be returned to the shell, where you can type other commands. You can then resume vim later on by typing fg or typing % followed by its job number.

You can kill jobs based on their number as well. In that case, you'd use kill %<jobnumber>, as in kill %2 to kill the job with job number 2.

![]() Tip Also useful is Ctrl+C, which will kill a job that's currently running. For example, if you previously started the

Tip Also useful is Ctrl+C, which will kill a job that's currently running. For example, if you previously started the unzip command in the foreground, pressing Ctrl+C will immediately terminate it. Ctrl+C is useful if you accidentally start commands that take an unexpectedly long time to complete.

NOHUP

Summary

This chapter has covered taking complete control of your system. You looked at what processes are, how they're separate from programs, and how they can be controlled or viewed by using programs such as top and ps. In addition, you explored job management under BASH. You saw that you can stop, start, and pause programs at your convenience.