Chapter 6. Tangible Futures

"The wind chime maker invites nature into collaboration.”

Animism is the belief that souls or spirits exist not only in humans, but also in animals, trees, mountains, rivers, wind, weather, and other natural objects and phenomena. It’s an idea that infuses philosophy and religion in countless cultures throughout history. It’s also a wellspring for myths: traditional stories that explain the origin of the universe, the history of a people, and the purpose of social institutions. One of the main functions of myth is to establish models for behavior. The narratives of Prometheus, Pandora, Sisyphus, Oedipus, and Odysseus are designed to instruct. Our familiarity with these ancient stories proves the power of myth. These lessons endure. They are made to stick.

Interestingly, in modern vernacular, a myth is a false story or belief, but within their cultures of origin, myths are sacred narratives that tell truths about the past. Today, myths have lost credibility, yet they still offer the power of reflection. Through metaphor and analogy, myths reveal the story of ourselves. Heroes, tricksters, and gods are but vessels for the personification of our own hopes and fears. Myths are mirrors. They catalog patterns of experience and expectation. They remind us that what’s past is prologue. More than just vivid stories of yesteryear, myths animate and act upon the future.

In design, we would do well to embed similar insight and influence in our deliverables. We need stories and sketches that bring search and discovery to life. We need principles and proverbs that capture the essence of human psychology and behavior. And we need maps and models that shape beliefs about what’s possible, probable, and preferable. After all, design is inextricably invested in the future. Our research reveals the latent desire lines that inspire new products, and our prototypes engage people in spirited discussions of strategy, technology, and experience. In an era where the hard things are the soft things, our work invests ideas with substance. We transform abstract patterns and proposals into physical artifacts with sensory and emotional resonance. While our hearts are in the betterment of communication and collaboration, there’s no question we’re in the business of persuasion. We change minds. Our prototypes and predictions influence the future, even when they’re wrong. We are the makers of maps and myths. We are entrusted with the authority to put the soul in search by making tomorrow tangible.

Methods and Deliverables

The design of search is a tricky business. Each project is unique. Restructuring an enterprise intranet, migrating an e-commerce experience to the mobile platform, and inventing a “new to the world” decision engine are clearly sisters of a different order. However, just as patterns of behavior and design transcend category and platform, so do our methods and deliverables. In fact, there’s nothing special about search. A standard issue user experience toolbox and a bit of advanced common sense are really all we need.

For starters, we must select research methods that fit the context. Unobtrusive field observation is rarely practical, since search is generally ad hoc. But we can surely draw upon other ethnographic techniques, including interviews, questionnaires, and diary study. Classic usability testing also works well, but it’s important to avoid oversimplification. Basic tasks (e.g., try to find) should be interspersed with real-world scenarios. Users must be free to search and browse. And it’s often useful to ask how people would normally find the answer or solve the problem if not with this specific site or application.

Search analytics are another obvious choice. For a website, it’s useful to compare the most popular internal and external queries. What’s the difference between the search terms that deliver people to the site and the queries they perform when they get there? By asking this question, we often expose gaps in marketing and design that we must address by improving both search engine optimization and the site’s information architecture. Of course, it’s important to recognize the limits of quantitative analysis. The data tells us the terms people use, but not what they seek or whether they succeed. A mix of methods helps us to interpret the data, place anomalies in context, and begin to see the big picture.

For that reason, it’s also vital to conduct internal meetings and stakeholder interviews. Since search is a multidisciplinary collaboration of design, engineering, marketing, and management, success requires that we engage participation across departments and units. Conversations should cover mission, vision, strategy, time, budget, human resources, and technology infrastructure. It’s also good to ask about metrics for success and models of best practice, since these questions elicit examples that bring discussions down to earth.

During discovery, and especially in these meetings, it’s important to turn the observer problem into an opportunity. Simply by being present and asking questions, we exert influence, subtle or not. The right nudges now can avert problems later. Even at this early stage, it’s worth visualizing and shaping both journey and destination.

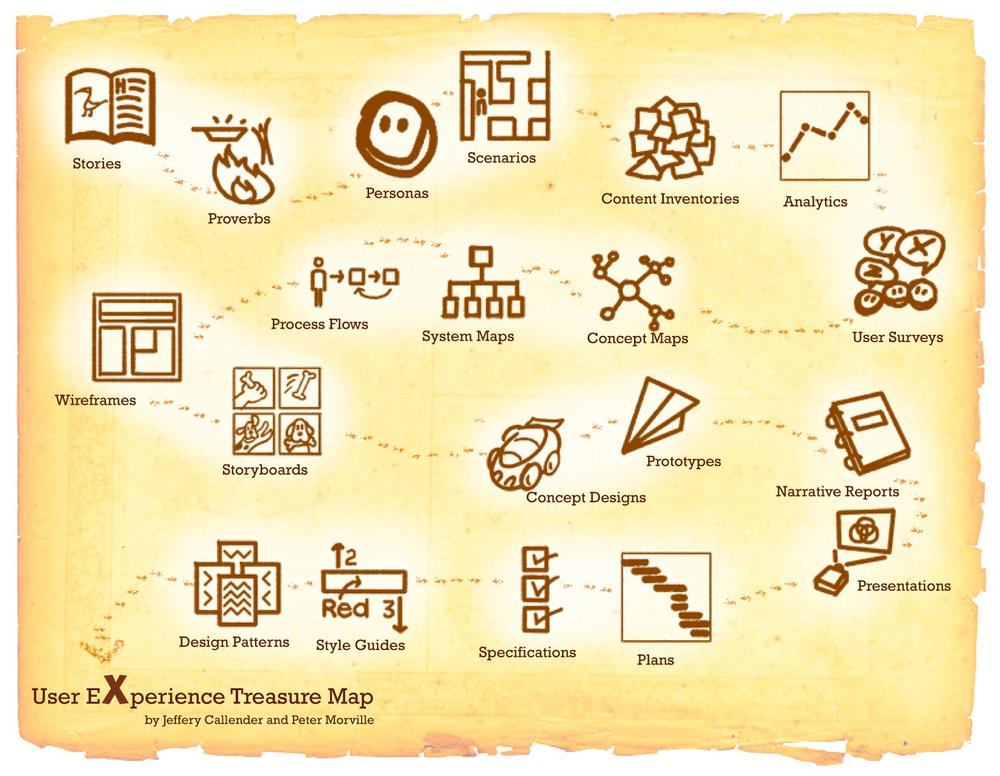

Similarly, we should invert our thinking about deliverables. Our artifacts are not just tools for persuasion; they’re also vehicles for exploration. A concept map lets us reframe the problem and elicit a response. A process flow lets us wander the actual and possible paths of users in search of shortcuts and serendipity. Prototypes afford the amazing opportunity to create, play with, and learn from tangible products of the imagination. We should heed the invitation of Figure 6-2 to lay out all our deliverables in one place so we can see them in context, consider their purpose, and enjoy the experience of discovery.[17]

Search Scenarios

So, in the spirit of play, we propose to explore the future of search and discovery through a series of scenarios. Our aim is not to predict but to persuade and provoke. As a result, our sketches and stories are divergent by design. We’ll wander in time and format from images of distant futurity to narratives that could take place tomorrow. As a group, our scenarios won’t cohere. But individually, like myths, we hope they stick. We want to inspire you to take risks by taking a few ourselves.

And now for something completely different.…

Sensorium

Anja felt happy. She was sitting cross-legged on Claire’s bed. She stole a last glance at the sun-dappled meadow before her best friend drew the curtains and collapsed into a giant pink bean bag in the far corner of the room. Of course, “happy” wasn’t the right word, but “elated” was over the top. “Playful” was good. She added “peppy” and “perky” to the query, then “pink” just for fun. Both girls laughed as the results tickled their senses. Images of bunny rabbits and puppy dogs spun into sight. A flock of butterflies flew by overhead. The warble of a barn swallow became a mountain stream, a flute, chimes in the wind.

Claire reached for the sensory controls, nudging up taste and smell, while tapping the soothing tag near the barn swallow icon. The girls sighed in sync as hot chocolate infused with hints of cinnamon and vanilla soothed their preteen limbic systems.

Anja spun the similar sensewheel and landed on s’mores, closing her eyes to savor the crunchy, chocolatey, smoky, sticky mess. A soft sob broke the spell. Anja looked up to see her friend in tears. Claire replied to the query on Anja’s face with, “I miss my mom.”

Claire’s mom had died the year before. The brain cancer was detected early, but it was too deep for surgery and unresponsive to drugs and radiation. That’s why the girls didn’t visit much anymore. Claire’s dad had moved to the country to “get away from it all.” Whatever that meant. They still hung out virtually every day, but it wasn’t the same as in person.

Claire sat quietly in the corner in her big pink bean bag.

“Show me,” Anja whispered.

Claire summoned a video wall with her left hand, her fingers and eyes dancing their way through a colorful montage of bedtime stories, birthday parties, sing-alongs, and other bittersweet memories that started sad but trended too quickly to sunlight and sugar.

“No,” said Anja softly, looking directly into her friend’s eyes. “Show me.”

Claire stared back for a moment, took a deep breath, then flipped the switch for emotive output. Anja gasped as feelings of loss, fear, anger, and guilt washed through her medial temporal lobes. She closed her eyes and covered her ears, but couldn’t shut out the pain. She felt like weeping and wailing and tearing her own flesh. The sensations of darkness and despair were unbearable, consuming, neverending. And then they were gone.

Claire joined Anja on the bed, and the two friends embraced. After tears had run their course, Claire caught Anja’s eye and conjured a rainbow that lit up the room. Anja responded with a flag waving in the wind. It was red, white, and pink. The game began anew. The girls searched and stumbled and smiled through their five senses and beyond.

Anja soon felt happy. Of course, happy wasn’t exactly the right word.

Debrief

A real sci-fi writer wouldn’t deign to explain the story and probably wouldn’t need to. But we dilettantes may add value by debriefing, especially when the tale is but a catalyst for conversation. In our flash fiction, we imagine a game of search in a world where neural implants afford direct sensory input and output. Queries and results can be rendered by touch, taste, sight, sound, or smell. Our matrix of hardware and wetware even enables the direct or indirect exchange of raw emotion. It’s a radical proposition, but not necessarily impossible and certainly not unimaginable. What could this future mean for search? What types of interfaces and interactions can we envision?

For starters, words will take us only so far. Perhaps the act or memory of sensing will form the query. Pearl growing and incremental construction—like that, but a bit more of this—will be vital. Progressive disclosure will guide the presentation of multiformat results by fading less popular senses into background options. Indeed, many people may enjoy the opportunity to try the cross-sensory experience of synesthesia, but we’ll need to employ our scented widgets, flavorful facets, and sonic snippets judiciously to prevent pogosticking ad nauseam. Don’t Make Me Sick might be Steve Krug’s next bestseller.

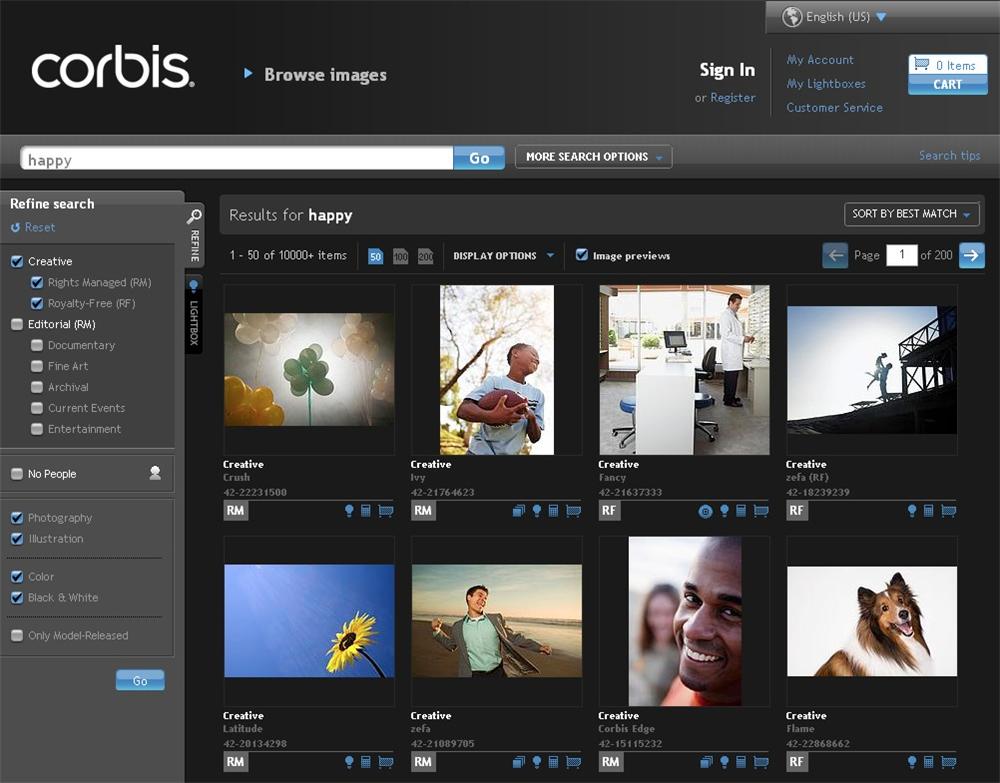

A good scenario doesn’t just provoke us to ponder the future; it changes how we think about today. Sensorium might, for instance, spur new ideas about stock photography.

Are keywords and controlled vocabularies really the best we can do? Or can we transcend the limits of language? Automatic pattern recognition is one option. Software that scans facial expressions to derive emotions shows real promise. But what else? What’s next?

Semantic Singularity

The entertainment system was belting out the Beatles’ “Let It Be” when the iPhone rang. When Pete answered, his phone turned down the sound by messaging all nearby devices with a volume control. Lucy, his sister’s agent, was on the line. “Mom’s at the hospital. She had chest pain. The doctors ran tests and established a diagnosis of.…” Lucy was cut off by Hugh, Pete’s agent, who appeared as a hologram on the table nearby.

“Hey Pete, I’ve bought you three pairs of running shoes, Nike+ LunarGlides, top of the line. I’m wearing a pair. Check ‘em out.”

“Hold on!” shouted Pete. “I’m on the phone with Lucy. Lucy, are you there? What’s wrong with Mom?” Lucy explained that Mom had an episode of angina. “She’s stable and should be fine. Jenny’s taking her home.” Pete promised to meet his mom and sister there soon, then turned his attention to Hugh. “So, what’s up with the Nikes?”

“Heart disease is hereditary,” replied Hugh. “You already have most of the risk factors. You’re male, inactive, and overweight. You drink too much. Your blood pressure and cholesterol are high. You’re getting older. Plus, you’re under stress. Your mom’s diagnosis pushed you from alert level orange to red: severe risk of heart attack. I’ve put together an exercise program. We’ll be running five days a week. Also, I’ve consulted with your doctor’s agent. You’ll be taking 80mg of Lipitor daily, starting tomorrow.”

Before Pete could argue, the doorbell rang and the fire alarm went off. He dashed into the kitchen, jerked the smoking pan of Chef Boyardee beef ravioli off the burner (apparently his phone had turned down the volume on his stopwatch), silenced the alarm, and ran to the front door. He was greeted by a teenage girl wearing a green striped uniform. “Delivery. Prepaid. Butternut squash in coconut milk with tofu and toasted almonds.” She handed him a box, warm and damp on the bottom, and left with a wave.

“What the hell is this?” Pete demanded back inside.

“Butternut squash,” replied Hugh. “It’s healthier than pizza. And we had a coupon.”

“But I don’t like squash. And I didn’t order pizza!”

“You swoogled for ‘pizza’ a half-hour ago. And you opted into that no-click ordering program last week. I did an autosuggest override and selected a heart-healthy option.”

“I was searching for ‘pisa,’ not ‘pizza.’ I’d like to see the tower before it falls.”

Hugh defended the autocorrect as statistically valid. He then presented a dynamic, three-dimensional fly-through visualization. “It’s a personalized decision matrix,” he explained. “Clearly, you’ve gotta run, go vegan, and take Lipitor. It’s your only hope.” Finally, he recommended a great hotel in Barcelona, and LightLife veggie burgers.

Pete couldn’t grok the data. He’d have to trust Hugh’s interpretation. But he wanted to visit Pisa, not Barcelona. And there was no way he was eating veggie burgers. “I’m leaving for Mom’s now. I’d like a large pepperoni pizza delivered to her house. Please cancel that shoe order. And disable your autosuggest override function, at least for now. I’m not changing my whole lifestyle just yet, and neither are you.”

Hugh shook his head. “I’m sorry, Pete, but you’re asking me to violate laws one and three. I can’t allow you to come to harm, and I must protect my own existence.”

Pete stared at Hugh in astonishment. Things were starting to get creepy. Then he noticed something. His eyes narrowed. “What’s that on your bow tie?”

“It’s nothing,” answered Hugh.

And it was nothing. Just a plain black bow tie. Pete stomped out of the apartment. His car was waiting in the lot, engine running, top down, radio on, door open. As the car drove off, Pete muttered to himself, “I could have sworn there was a logo on that bow tie.…”

Debrief

This scenario is a parody. It mocks “The Semantic Web” by Tim Berners-Lee et al. (Scientific American, May 2001). It also pokes fun at Ray Kurzweil’s The Singularity Is Near (Viking Adult) and Apple Computer’s "Knowledge Navigator.” These works were authored by brilliant people. They advanced groundbreaking insights and ideas, but they all failed spectacularly to predict the future of human-computer interaction (so far).

While artificial intelligence lies behind each vision, search is often the killer application. The idea that software agents will answer our questions (sometimes before we ask) via a conversational interface is seductive. We also love to imagine an orderly world of cooperative systems and appliances. But life and language are messy. Crosswalking for meaning across vocabularies and standards is difficult, if not impossible. Then there’s the trouble with trust; the smarter the agents, the harder they are to trust.

In this scenario, the agents possess a scary level of control. Even when they’re not actively making decisions and performing tasks, the agents control access to information. Their alerts, algorithms, and filters influence which facts are found and whose opinions come first. And they just might be working for someone else, or for themselves.

Of course, it may be premature to question the ethics and motives of our agents. While it’s cool that WolframAlpha can answer a few big questions, in truth, semantic search hasn’t progressed much beyond parlor tricks. Software can extract a little more meaning from natural language texts and questions by parsing sentences for actor-action-object triples, but simple keyword queries generally remain the most efficient way to start.

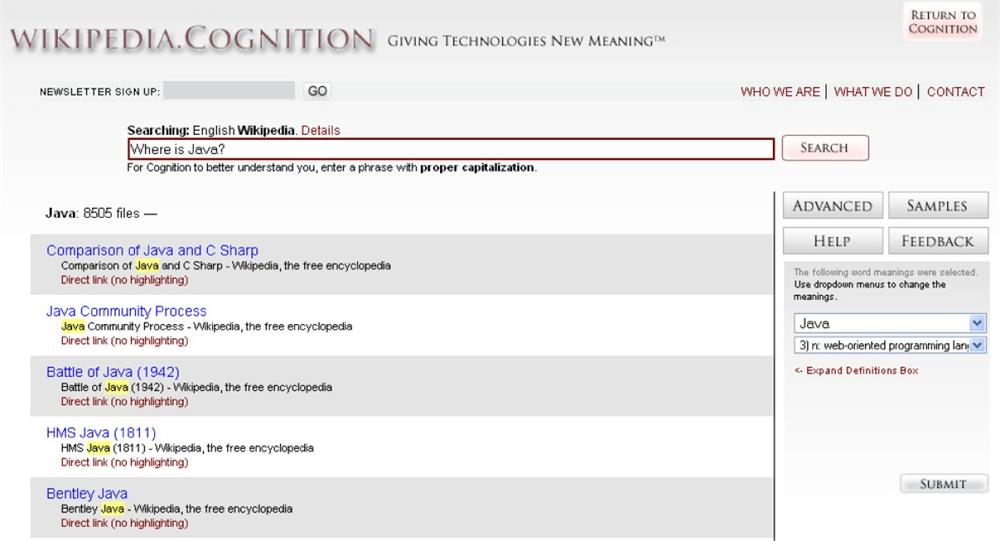

There’s a big gap between the claims of semantic search companies and the performance of their products. Consider, for instance, this excerpt from Cognition’s website:

" Cognition’s natural language technology employs a unique mix of linguistics and mathematical algorithms which has, in effect, taught the computer the meanings (or associated concepts) of nearly all the words and frequently used phrases within the common English language. It also has knowledge of the relations between words and phrases, especially paraphrase (a ‘finger’ or a ‘digit') and taxonomy (a ‘finger’ is part of a ‘hand', a ‘cow’ is a ‘bovine’ and is a ‘mammal').”[18]

Cognition goes on to explain that its software “understands the meaning within the context of the text it is processing.” So, why can’t it figure out that a user who asks, “Where is Java?” is probably looking for a place, not a programming language? (To its credit, WolframAlpha nails this one, serving up a link to Java Island and a map of Indonesia, which is great provided you’re not looking for Java, South Dakota.)

It’s not that there’s no value in parsing sentences for meaning or developing thesauri (or ontologies) that map equivalent, hierarchical, and associative relationships. These approaches can add value, especially within verticals with limited, formal vocabularies like medicine, law, and engineering. It’s just that less obvious approaches—like employing query-query reformulation and post-query click data to drive autosuggest—may deliver better results at lower cost. And we should be wary of claims that computers “understand meaning,” at least until they get a whole lot better at filtering spam.

But we don’t need the future to worry about trust. Google already shapes what we find, learn, and believe. And Google isn’t transparent; it is a multibillion-dollar company that earns nearly all its revenue from advertising and maintains its ranking algorithm as a closely held trade secret. Google knows more about us than we know about Google. Google claims that because of personalization, the more we share, the better the results. How do we know we can trust Google? Is “Don’t be evil” enough? Should we continue to search and share in good faith? Or is evil subject to interpretation? Is it possible that personalization is more about targeted advertising than relevant results? However we answer these questions, the fact is that ranking algorithms are an invisible yet powerful force in our lives. Their power will only grow. What about their visibility?

Searchvalence

Jen realized she’d lost Bruce when she found his iGlasses on a shelf in a used bookstore on Castro Street. They’d planned to meet up after her walk through Golden Gate Park. But now what? He could be anywhere. Deciding she’d rather spend a little money than a lot of time, Jen fired up Google’s PeopleFinder.

Debrief

In urban environments, we’re already surrounded by video cameras, some integrated with microphone surveillance systems that can recognize a discrete sound, identify the point of origin, and turn cameras to focus precisely on that location. Imagine these cameras networked and their streaming video and audio available to the public for a fee. Now add iGlasses with Life Caching A/V worn by everyone who’s anyone, and a layer of sophisticated face and voice recognition software. Maybe we’ll have smart sidewalks and floors to track people by their unique footfall signatures. And don’t forget the radio-frequency identification (RFID) tags in our wallets, shoes, and underwear—and perhaps a FriendChip™ or two under our skin.

Sure, this prospect may seem a bit spooky, but it’s worth thinking through some of the intriguing possibilities. For instance, what if we could watch and listen through another’s eyes and ears, assuming they gave us permission? This is already happening in a crude way. Just watch all the cellphones held high during an Olympic Opening Ceremony. And don’t forget the life cache—we’ll be able to see and hear history in the making, for a price. Designing search for this scenario should be interesting, especially since the best insights may emerge from the collective motion and behavior of crowds.

Flock

Paul was looking forward to a late lunch with his three girls. The Black Sheep’s turkey club was awesome, and the girls said the Grandma Cake was to die for. And, as Bing had predicted, the deli was quiet this afternoon. Before they could grab a table, Paul’s mobile beeped. It was a SIQ alert.

Debrief

Imagine you’re sitting on a plane when the captain announces (without explanation) an indefinite ground stop on all inbound and outbound aircraft. Or you’re sitting on the grass in Central Park when a jumbo jet pursued by two F-16 fighters flies low over downtown Manhattan. How do you learn what’s going on? If it’s a major event, CNN will pick it up eventually. But what about right now? Increasingly, a real-time search on Twitter is the fastest (albeit not the most authoritative) source of information.

It’s not hard to foresee that we’ll soon be relying on data about what people are saying, doing, and searching for—right now—to influence our own actions, decisions, and destinations. Google is already able to predict over half of the most popular queries in a 12-month forecast with a mean absolute prediction error of 12 percent.[19] Add location and personalization, and you’ve got an excellent baseline for identifying interesting new trends and deviations from the norm.

Clearly, real-time access to social activity metrics might alert us to news before it’s news. It might also help us find the most popular nightclub or the fastest route through rush hour. Of course, we’ll have to endure accidental flash mobs, as everyone spontaneously and simultaneously decides to visit the same unusually quiet café. We may have to pay good money for access to the best predictive algorithms and social signifiers, but this capability could add sense and shape to our collective (and individual) behavior.

Experience Discovery

These search scenarios are simple tools for engaging people in thought and conversation about possible and preferable futures. We can explore more sophisticated artifacts on video-sharing sites, such as YouTube, which overflow with prototypes and provocations concerning the future of food, communication, learning, health, cars, kitchens, mobile devices, and the Web. As experience designers, we have a wide spectrum of hot and cold media from which to fashion our images of the future. We may employ the logic and order of a formal presentation to persuade one audience while relying on the nonlinear nature of a preliminary sketch to draw a different audience into participatory design.

This diversity of formats is among the reasons we’re seeing convergence in the practices of futures studies and experience design. Futurists and forecasters understand the degree to which the impact of what we say is influenced by how we say it. In fact, Jason Tester of the Institute for the Future argues for a new discipline of Human-Future Interaction (HFI) that integrates futures thinking with the methods and deliverables of HCI. He defines HFI as “the art and science of effectively and ethically communicating research, forecasts, and scenarios about trends and potential futures,”[20] and notes the importance of user testing and rapid, iterative prototyping. Jason explains that “a growing view of the future as a medium that anyone can affect and co-create” means this work has value and resonance far beyond the walls of traditional think tanks and forecasting groups.

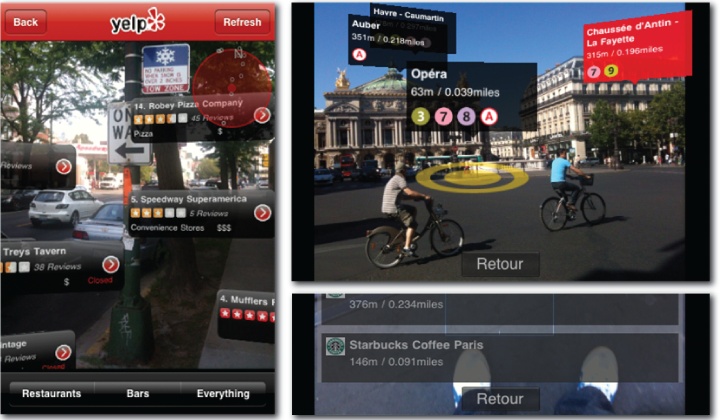

As designers, we’ve always had one foot in the future, but in search and discovery the pace of innovation is forcing us to jump head first. Consider augmented reality (AR), for example. Until recently, mainstream AR was limited to the yellow “first down” line in television broadcasts of American football. But now AR applications like Wikitude, Layar, and Yelp’s Monocle are flourishing on Android mobiles and the iPhone 3GS.

While early adopters may be frustrated by problems with technology, design, and data quality, this ability to overlay information on the real-time camera view by using the GPS, compass, and accelerometer to determine location and direction is clearly a game changer for mobile search and discovery. All we need now is the heads-up display!

Of course, we have much work ahead: uncovering valuable use cases, identifying successful design patterns, and defining a vocabulary for talking about mixed reality that encompasses both augmented reality and augmented virtuality (the merging of real-world objects into virtual worlds). Since we can’t rely on the old desktop metaphor, we must invent new idioms for communication and interaction. Already, we’re seeing terms like “magic lens” and “enchanted window” to describe AR, which suggests that Mike Kuniavsky and Brenda Laurel are ahead of the game.

For several years, Kuniavsky has been an advocate for what he calls the coming age of magic:

" I mean enchanted objects. What I’m proposing is a metaphorical relationship between magic and portable, network-aware, information processing objects that is analogous to the relationship between office supplies and computer screens in the desktop metaphor. I am explicitly not advocating pretending that technology is a kind of magic or lying about how technology works, but using our existing cultural understanding of magic objects as an abstraction to describe the behavior of ubiquitous computing devices.”[21]

He notes that what differentiates enchanted objects is “their ability to have independent behaviors, to communicate, to remember, and to interact with other enchanted objects and people” without screens or keyboards. Magic as a metaphor, Kuniavsky argues, is an emergent, familiar pattern that transcends culture, material, and context.

In similar fashion, Laurel has advanced the concept of “designed animism” as a way of framing our relationship with objects in wireless sensor networks:

"Sensors that gather information about wind, or solar flares, or neutrino showers, or bird migrations, or tides, or processes inside a living being, or dynamics of an ecosystem are means by which designers can invite nature into collaboration, and the invisible patterns they capture can be brought into the realm of the senses in myriad new ways.”[22]

She suggests that by marrying animism with a sense of poetics, we can tap the affordances of ambient computing to invent new forms of pleasurable experience. We can change the world through delight. It’s an intriguing vision that encourages us to weave elements of magic, myth, emotion, and empathy into the tapestry of our future.

Fortunately, we can’t predict the future. We can barely forecast the weather. To pretend otherwise is an act of hubris, the greatest sin in the eyes of the ancient gods. It’s this uncertainty that makes Horace’s lyric poetry both tempting and timeless: Carpe diem quam minimum credula postero, or “Seize the day; trust tomorrow as little as you may.”

Delightfully, there’s no shortage of problems with search today. Even as we speculate about the Future with a capital F, Google is quietly figuring out how to disambiguate GM (General Motors or genetically modified). For every unsolved problem, there are countless instances in which we know the solution, but nobody has bothered to implement it. Discipline and attention to detail would go a long way toward improving the world of search. A heads-down focus on the tasks of today can often produce both pleasure and progress.

But we’d be remiss in our responsibility if we ignore the shadow of the future. We’re not simply in the business of designing experiences. We must also grasp the curious, collaborative challenge of experience discovery. By investing in exploratory research and experimental design, we can work with our users to discover and cocreate new products, inventive applications, and desirable experiences. This will require insight and foresight.

To make search better, we must embrace the genius of the AND. We must look to the center and the periphery. We must learn from fact and fiction. We must use compelling stories and colorful artifacts as our microscopes, telescopes, and kaleidoscopes. It’s not sufficient to adopt and adapt patterns. We must innovate. We must bring search to life. To accomplish these lofty goals, we must entertain both the present and the future.

In this adventure, we might employ the butterfly effect as a metaphorical bridge between tomorrow and today. The term derives from a short sci-fi story by Ray Bradbury in which a hunter from 2055 travels into the past on a prehistoric safari, accidentally kills a butterfly, and returns to find his present has been changed in subtle yet meaningful ways. The phrase was given new life by Edward Lorenz, a mathematician and meteorologist who pioneered chaos theory by discovering how sensitive dependence on initial conditions shapes weather patterns. He’s credited with the aphorism that the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil could set off a tornado in Texas.[23] This fact, that little things make a big difference, governs all complex systems, and it certainly applies to search.

Our work helps people find the products, places, and information they need, and the data that makes a difference. As designers of applications for search and discovery, we shape the future of learning and literacy. Search plays a vital role in the curation of knowledge and the provocation of creativity. It’s poised to engage our senses and lift our spirits in ways we can barely imagine. It’s a topic both timely and timeless. Search is a core life activity, as ancient in its form as the trees and hills, and as our faces are. We must discover its patterns, and break them with intent. Let’s get flapping!

[17] For more on this topic, see "User Experience Deliverables,” by Peter Morville and Jeffery Callender, available at http://semanticstudios.com/publications/semantics/000228.php.

[20] “The case for human-future interaction,” by Jason Tester, available at http://future.iftf.org/2007/02/the_case_for_hu.html.

[21] “The Coming Age of Magic,” by Mike Kuniavsky, available at www.orangecone.com/tm_etech_magic_0.3.pdf.

[22] “Designed Animism,” by Brenda Laurel, available at www.tauzero.com/Brenda_Laurel/DesignedAnimism/DesignedAnimism.html.

[23] Due to Edward Lorenz’s discovery of strange attractors, their visual representation, which illustrates order underlying chaos (pictured in Figure 6-11), is known as a Lorenz butterfly.