FLL is a unique competition. Unlike science fairs or robotics competitions, it consists of a wide range of team challenges that require individuals to combine many different skills to excel.

A new team may find the many aspects of FLL a little confusing at first. If this describes you, we’d like to help! In this chapter, we’ll explain each category of the competition and how it works.

Although FLL is sometimes thought of as a robotics competition—like its counterparts FIRST Tech Challenge (FTC) and FIRST Robotics Competition (FRC)—robotics actually make up only half of the challenge. FLL has four different categories:

Robot Game

Project

Robot Design

Teamwork

These categories are combined into exciting competitions called tournaments. The following sections give an overview of tournaments and then describe the specifics of each category.

Tournaments are the climax of an FLL season. At a tournament, teams deliver their Project presentations, attend Robot Design and Teamwork interviews, and compete in the Robot Game.

Regions throughout the world host championship tournaments. The winners of these tournaments move on to the next level; qualifying tournament winners move on to the state tournament and so on. For example, in the United States, winners of state championships compete in national or international invitational tournaments.

The World Festival is a huge international invitational tournament composed of some of the best teams from around the world. Although it isn’t the culmination of all championships, it is one of the most celebrated and prestigious tournaments. Learn more about upcoming FLL tournaments in your area on FLL’s website, http://www.firstlegoleague.org/.

The Robot Game is one of the robotic categories of FLL, and it is one of the most well-known and exciting parts of the competition. For this challenge, teams have three to five months (the actual time depends on the region) to build and program a LEGO MINDSTORMS robot to autonomously accomplish several missions on a 4-by-8-foot playing field in two-and-a-half minutes. Autonomous means that the teams may not remotely control the robots. The robots compete for points by accomplishing as many missions as possible during a match.

Note

The two-and-a-half-minute time frame during which robots attempt their missions is called a match. A round consists of each team at a tournament completing one match.

At the beginning of each new FLL season, teams receive a kit that includes a field mat, LEGO pieces, instructional materials, and other supplies to get started. Let’s review these supplies, starting with the field mat.

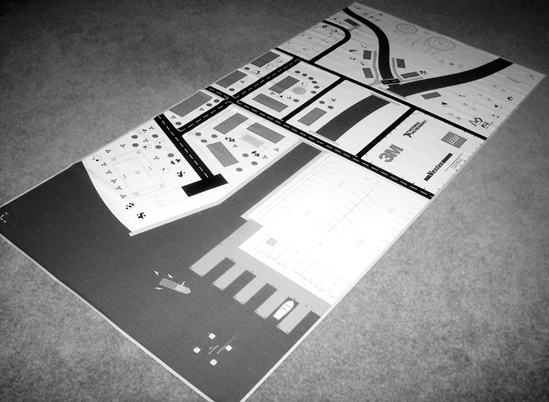

The field mat is a flat, flexible, 4-by-8-foot plastic mat that makes up the area on which the robots compete. Graphics on the mat depict a virtual environment related to the competition theme. For example, the mat for the 2005-2006 Ocean Odyssey season pictured an ocean environment. Figure 2-1 shows the field mat used during the 2007-2008 Power Puzzle season.

The mat should be set on a hard, smooth, and level surface, surrounded by 4-inch-high black borders (usually made out of 2-by-4-inch pieces of wood). At tournaments, the mats are usually set on custom-made tables, but teams can use other surfaces and borders for practice.

Note

It’s fairly easy to build an official table. Find instructions for doing so on the “Field Setup” page of the FLL challenge website. We suggest that you use an official table to practice to make your preparation as realistic as possible.

Although most graphics on the field mat are decorative, some represent scoring areas where certain objects (or even the robot) must be delivered to or taken away from to score points. Other graphics are represented for strategic reasons. For example, black lines may be part of the virtual environment (such as roads), but a robot’s Light Sensor may also use them for navigation. Look for features on the mat that might help your robot navigate.

Field mats also include an area called Base, which is the robot’s starting point. The Base is a three-dimensional area 16 inches (40 cm) high, surrounded by graphics and one side of the field. Figure 2-2 shows the Base on the Power Puzzle mat.

At the start of each round, the team’s robot must be completely inside the Base area, which restricts the size of the robot and ensures that all robots start each round in the same place. Also, if the robot must be rescued (as discussed in The Match in Delivering an Object to a Model), it must be completely inside the Base before it can autonomously start again.

Mission models are the LEGO constructions that are involved in all missions. For example, a mission might require robots to push a lever on a building made out of LEGO pieces, which is a mission model.

The Field Setup Kit contains a bunch of LEGO pieces that make up the mission models, as well as a CD with instructions on how to build them. For example, Figure 2-3 shows the mission model components for the Power Puzzle season.

Building the mission models is a great activity for a first team meeting as a warm-up or introduction. The building itself can take a few hours, so it might be helpful to print out the instructions so multiple people can build at the same time. On the other hand, if the team wants to start on the robot right away, one member may want to build the models during spare time.

Once you build the mission models, attach them to the field mat with Dual Lock—a fastening material similar to Velcro—which comes with your Field Setup Kit. The field mat shows where to place the mission models and the Dual Lock.

Note

If you’re not sure how to use Dual Lock, FLL has instructions on how to use it, along with other useful field setup instructions, on its website.

Mission models create a variety of challenges for robots, which usually have to perform the following four types of actions with the models:

Transfer the model

Activate the model

Deliver an object to the model

Remove an object from the model

This action involves moving a mission model from one location on the mat to another. When a mission involves this action, the model that will be moved is not attached to the mat with Dual Lock—it simply rests in a specified position. For example, in the Power Puzzle season, the Hydro-Dam had to be moved on the mat from Base to a river so that the model touched both banks of the river without touching any of the houses nearby.

Activating a model involves doing something to make it react in a specific way. For example, in the 2006-2007 Nano Quest season, the Self-Assembly mission required the robot to flick a lever on the mission model to start a chain reaction. Models that require an activation action are usually attached to the mat with Dual Lock so the robots can activate them without moving the entire model.

Sometimes a mission model includes an object that isn’t attached to the main model. Instead, this object usually starts in Base, and the robot has to deliver it to a specified place on the main model. In the Nano Quest season, for example, one mission required robots to deliver an object from Base to a mission model and drop it onto a lever that then caused a wheel on the model to spin.

Some missions require robots to remove one or more objects from a mission model. For example, the Oil Drilling mission of the Power Puzzle season required robots to move three oil barrels from an oil platform and place them safely ashore. Points were deducted from a team’s score if the barrels touched the water (ocean).

At a tournament, tables are set up with two field mats next to each other and their four-inch-high borders connected. The mission models are placed on the mats.

Two teams compete on a table—one on each field mat. Although they are next to each other, the teams only interact on one mission model that is on the border between their field mats. Sometimes, the two robots compete to accomplish the mission first (with the winner scoring more points). Other times, the teams work together to accomplish the mission, with both teams scoring the same number of points if they succeed.

Each team may have two members act as drivers of the team’s robot. The drivers set up the robot in Base before the match, run the programs, and manage the robot during the match. Drivers can change places with other team members, but only two drivers can be at the table at once.

When the drivers are ready, the announcer counts down, “3 . . . 2 . . . 1 . . . LEGO!” and the teams start their robots. The robots have exactly two-and-a-half minutes to accomplish as many missions as they can.

If a robot gets stuck, the drivers can rescue it by picking it up and returning it to Base, though they risk losing points. They may grab their robot without penalty if any part of it is already touching Base—whether to modify it, reposition it, run another program, and so on.

The winner of the Robot Game can be determined in different ways. Sometimes teams compete in three or more competition rounds for the highest single or combined score. Other times, the top scorers move into elimination rounds in which teams compete in pairs and the winners of each pair move through successive rounds until one team wins. It’s very exciting to watch the Robot Game—and even more exciting to compete in it.

The Project is one of the two nonrobotic categories of the FLL competition and has a bit of a science-fair style. Teams research and solve a real-world problem based on the challenge theme and present their research and solutions to their community. Community refers to local organizations, governments, companies—anything. The teams are also encouraged to impact their community in their research area (discussed in the Presentation section) and will typically be asked about this during a judging session.

At the beginning of the FLL season, the details and rules of the Project are posted on FLL’s website at http://www.firstlegoleague.org/ (click the link for your country, go to the current year’s challenge page, and click The Project). The rules describe the Project’s theme, general topic, and any special activities the teams have to do as part of the Project.

Once the Project rules are posted, each team needs to choose a topic related to the theme. For example, in the Nano Quest season, in which the general theme was nanotechnology (the manipulation of atoms and molecules), a team might have chosen “Nanotechnology in Medicine” as its topic.

Once the topic is chosen, research it. For many Projects, you need to suggest a solution to a problem. For example, in the Power Puzzle season, the Project required teams to come up with ways to make a building more energy efficient.

You can perform your research anywhere, but keep in mind that judges like to see original research, such as personal interviews with scientists or information discovered during the team’s experiments. Be sure to take good notes because you’ll include your findings in a presentation that you give to members of your community and, ultimately, the FLL judges (learn more about the research portion of the competition in Chapter 15).

Once your team has enough information, create a presentation for the judges at your tournament(s). The only requirement is that the presentation is shorter than five minutes (including setup), but otherwise, teams can give just about any kind of presentation they want. Possible presentation styles include PowerPoint presentations, plays, videos, speeches—even operas!

Whatever your presentation, include as many team members as possible to demonstrate good teamwork and to show that the entire team contributed to the Project. The number of participating team members will probably affect your score. If many or all of the members participate, your score will most likely be higher than if only a few participate.

During the presentation, identify the real-world problem you researched and your proposed solution, and discuss the research you performed. Make sure the team members know the material well and can clearly and smoothly present their pieces without reading from notes.

The judges will then ask the team members questions related to the presentation. Among other things, they look for evidence that the members did all the work and have a good understanding of the information related to their presentation.

In addition to presenting your Project to the judges, remember that part of the Project includes presenting your research and solutions to the community. One of the goals of FIRST is to get students interested in science and technology, so judges like to see evidence that a team has reached out to the community—the more, the better. Presenting scientific and technological results is important to scientists or engineers, and this aspect of the challenge gives team members valuable real-world experience in public speaking.

You can share your Project in several different ways. One common and effective way is to give your presentation for a group, such as a school, club, or even a senior living facility. Many seniors love seeing students learning about breakthroughs and accomplishments in science and technology that weren’t around when they were young.

You might also consider adding some extras to your presentations. For example, give a short talk about FIRST and FLL, or offer more detail than you are able to give in the tournament (where presentations are limited to five minutes). You could even demonstrate your robot to make things more exciting.

Another kind of community outreach involves working with government or private organizations to impact your community in the area of your research. For example, if a team picked “Nanotechnology in Medicine” for its Project in the Nano Quest season, they could have talked to an area hospital about implementing some of the technology they researched. Even if the organization doesn’t use your suggestions, the simple fact that you worked with them and tried to make an impact on the community is a nice addition to your Project. It will help your score, and best of all, it is a tremendous learning opportunity for the team.

In the Robot Design category of the competition, judges give a subjective score of the robot’s design.

The judges will ask about the design of your robot in an interview called the technical interview (or Robot Design interview). For example, they’ll probably ask how your robot works, how you built and programmed it, and how you overcame obstacles with its design. Many times they have a table set up with a field mat so you can show your robot in action. The judges look for well-designed robots that can accomplish missions in consistent, clever, and/or unique ways. They also look for evidence that the team members did all of the work on the robot (without the help of coaches or mentors) and evaluate the ways the team approached their particular design challenges.

The Teamwork category focuses on team dynamics—how team members work together. Your score for this category is partly based on how well you perform in an interview with the tournament judges. In evaluating teamwork, the judges consider the following categories, taken directly from the FLL rubrics (each is explained below):

Judges have multiple ways of determining how well teams do in each category. For example, in the Teamwork interview, they may give the team a challenge, then make an evaluation based on how the team tackles that challenge. They also watch teams throughout the tournament and sometimes interview a team at their pit area (the team’s home base).

When evaluating the team in the roles and responsibilities category, the judges like to see teams that assign specific roles and distribute work among the members. For example, is there a Lead Programmer or Battery Manager? The judges also like to see members covering for each other as necessary. For example, if one member is sick, does another cover for that person? Chapter 6 discusses ways to determine team roles.

Gracious professionalism is one of FLL’s core values. The FLL Coaches’ Handbook describes gracious professionalism as follows:

Gracious attitudes and behaviors are “win-win.”

Gracious folks respect others and let that respect show in their actions.

Gracious professionals make a valued contribution in a manner pleasing to others and to themselves as they possess special knowledge and are trusted by society to use that knowledge responsibly.

Put simply, gracious professionalism means acting graciously and respectfully to teammates, other teams, and visitors to the competition. For example, if some of the teammates disagree about what to include in the Project presentation, the judges will expect the teammates to listen to one another and professionally resolve the disagreement. Gracious professionalism also applies to interactions with other teams (you might also call this good sportsmanship). For example, although this is a competition, the winning team should not attempt to put down the losing teams. By the same token, if one team loses a piece at the tournament and another team loans an extra to them, judges viewing the action will most likely increase the loaning team’s score.

The Teamwork judges are also interested in how teams overcome obstacles or solve problems they encounter. For instance, if a robot starts acting strangely the day before the tournament, the judges will probably be very interested in hearing how the team tackled that challenge. They look at how the members work together as a team, regardless of whether or not they ultimately solve the problem. The judges like to see evidence that all the members helped to solve the problem, working together and respecting one another’s ideas.

During the interview, the judges look at how teams answer questions to see how enthusiastic and confident the members are. They also consider how many team members participate in answering questions; the more, the better, of course.

Finally, judges consider how well team members understand FLL values and how much they learn from the FLL experience. For example, they listen for a demonstrated interest in science and technology on the part of the team members. They also want to hear that the team has learned useful things from participating in FLL, whether they learned how to build and program robots, how to present to large groups, or anything else.

As mentioned earlier, sometimes the Teamwork category includes a surprise challenge that the team first learns about only in the Teamwork interview. These challenges differ for each tournament and can include just about anything. For example, one challenge in a tournament during the Nano Quest season required teams to build the tallest possible structure out of (uncooked) spaghetti noodles and mini-marshmallows. Teams have a limited amount of time to attempt the challenge. As they work on the challenge, judges look at how the members interact, how many participate, and how they perform in other aspects of the Teamwork category.

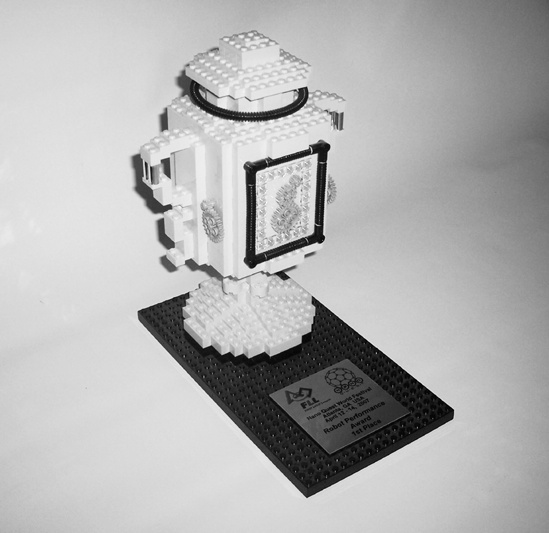

What’s a competition without trophies? FLL tournaments usually give out several awards. They are often made out of LEGO bricks, like the trophy shown in Figure 2-4. Most tournaments give out at least the following five main awards:

Robot Performance Award

Robot Design Award

Project Award

Teamwork Award

Champion’s Award

The first four awards are given to the teams who do the best in the respective categories of the competition. The Champion’s Award is considered the highest award in FLL, and it usually determines which team moves on to the next championship tournament. It is based on all four categories of the competition, and each category is weighed equally.

Note

Teams can only win one of the Championship Tournament Awards, unless the winner of the Robot Performance Award, for example, also wins the Champion’s Award. Each team may also win awards in only one championship series.

Many tournaments give other awards as well. For example, some reward outstanding coaches or mentors. Others, such as the Rising Star Award, are awarded to teams that give an exceptional performance in some area even though they’re not a winning team.