Scaling is how leaders transform a business idea into a large company. Leaders accomplish this transformation by positioning the company to capture growth opportunities while reinventing the company as it grows.

Scaling stages and startup stakeholders

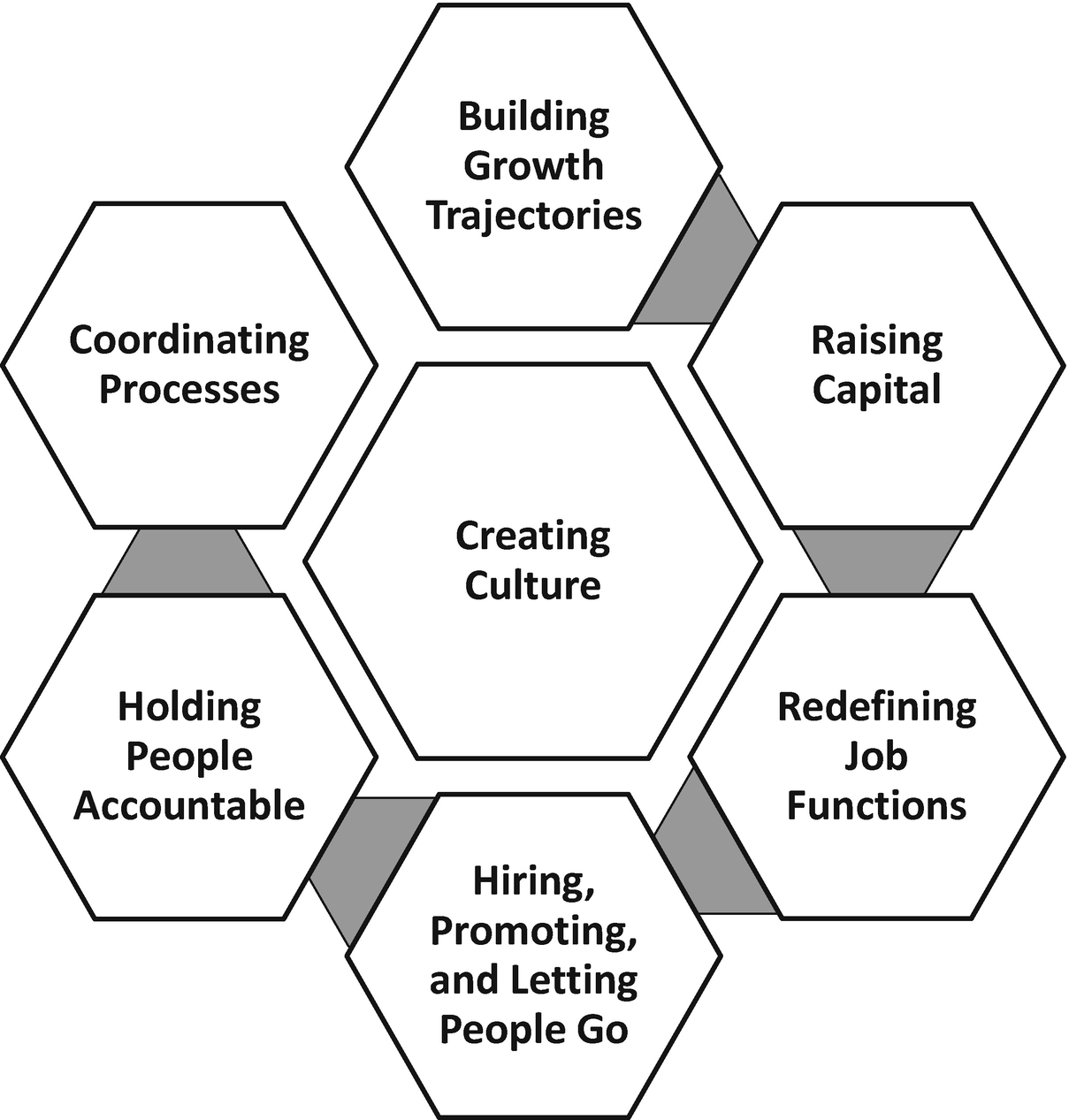

Seven startup scaling levers

Creating culture: Culture is what a company’s CEO and leadership team value most and how the company uses those values to select, motivate, reward, and let go people who work there. Companies that scale successfully reward employees who take responsibility for building and sustaining customer relationships as technology, customer needs, and the competitive landscape evolve. By contrast, companies that do not scale either have the wrong culture or fail to sustain the right one. For example, when a company is small, its first employees implicitly understand the culture and are in frequent communication. When a company starts to grow and hire new people, the culture will only survive if the CEO takes time to formalize it by explicitly defining the company’s values, telling stories about each value, communicating the stories to the company, and using the values to hire, reward, and let go people. While the company’s culture is likely to stay the same as long as the CEO remains in place, the process of sustaining its culture requires the CEO to formalize and communicate it in a disciplined way as the company scales.

Building growth trajectories: As I wrote in my 2017 book, Disciplined Growth Strategies, companies seeking to sustain their growth must build growth trajectories. Leaders create growth trajectories by creating chains from five dimensions of growth: customer group (current or new), product (built or acquired), geography (current or new), capabilities (current or new), and culture (current or new). Companies that scale successfully excel at planning to jump on a new growth curve in a new dimension even as their current source of growth is peaking. By contrast, startups that fail to scale wait too long to invest in a new dimension, pick the wrong one, or are simply unsuccessful when they attempt to expand because their skills do not enable them to win new customers there.

Raising capital: Once a startup has figured out its growth trajectory, the CEO is better positioned to persuade capital providers to invest. But as I wrote in my 2012 book, Hungry Start-up Strategy, the source of startup capital varies depending on its stage of development, which corresponds to the next revenue tier it aspires to reach. During the prototyping stage, when a company is trying to fit the features of its product to a specific unmet customer need, CEOs may want to seek out financing from founders, friends, family, or possibly crowdsourcing. In the customer base stage, when a company is seeking to reach revenues of $25 million to $50 million by adding many new customers, angel investors may be the best source of capital. And in the expansion stage, where the startup may be seeking to reach $100 million in revenue, venture capitalists may be the best source of funding. CEOs who can raise capital from the right sources at each stage of development often scale successfully, while startups with CEOs who lack this ability often run out of money before they scale.

Redefining job functions: As startups grow, leaders must change their organizations to adapt to the evolving needs of customers, employees, partners, and investors. Leaders do this by adding new jobs, changing existing ones, and eliminating others. For example, when a startup has a team of 10 or 20 people, they have a clear idea of the startup’s mission and take it upon themselves to perform many job functions. As the company grows, leaders define jobs more narrowly, for example, by separating the role of the head of human resources into more specific jobs for recruiting, benefits administration, and compliance, and adding a chief people officer role staffed by someone who excels at leading people in these specific jobs. Successful CEOs anticipate how job functions must change as a company scales while less effective leaders wait until a crisis hits before recognizing the need to change.

Hiring, promoting, and letting people go: As startups scale, leaders must fit the right individuals into these evolving job functions. To do this well, leaders must hire talented people who have succeeded in these roles before or promote current employees into these jobs. At the same time, leaders must part ways with people who no longer fit within the redefined organization, which can be particularly painful for founders who must let go people with whom they have worked for years. Successful CEOs constantly monitor how well people are performing in their evolving roles, are actively engaged in recruiting and training key talent, and firing those who no longer fit, while less effective leaders resist the need to evaluate how well people are performing and are reluctant to replace long-time colleagues.

Holding people accountable: As a company adds business functions, it becomes more difficult for a leader to give each person specific goals and hold them accountable for achieving those goals. For example, to scale a startup, the CEO may seek to increase its revenues in a given year from $25 million to $50 million. And while it may be easy to assign a portion of that desired revenue growth to each sales person, it is more challenging to determine the specific goals for people in product development, human resources, customer service, and other non-revenue-generating functions. Successful CEOs establish and apply rigorous processes that hold all people accountable for contributing to the startup’s growth goals. Such processes assure that each person is willing to strive toward their goals, and the CEO must be confident that achieving the targets will boost the startup’s scale. Less successful leaders lack such formal processes or do not implement them rigorously. As a result, their startups are at higher risk of stagnation.

Coordinating processes: CEOs organize people into departments by function and hold them accountable for corporate goals. While such functional specialization boosts efficiency in each department, it can also motivate leaders of each function to gain more resources by taking them from other departments. Unless CEOs create and manage processes to encourage departments to work together, the disadvantages of specialization can overwhelm the advantages. Simply put, leaders make the best use of a company’s talent by first differentiating and then integrating. And to scale their companies, the most successful CEOs achieve corporate goals through business processes such as adding new customers, increasing revenue per customer, hiring and motivating top talent, and scaling the culture globally. Less successful leaders struggle to create such formal processes as their companies scale, which makes their companies less efficient and slower to adapt to change.

Let’s examine now how startups use the seven scaling levers to interact with stakeholder at each stage.

Stage 1: Winning the First Customers

Every startup begins with an idea, and the best startup ideas alleviate customer pain better than any other product available to those customers. In this first scaling phase, the founder has no employees, investors, or partners and may have brought on a cofounder or two from among the pool of potential employees. To boost the odds for success, the founder should bring on cofounders who complement their strengths, performing well the specific activities that are important to the venture’s growth but are not the founder’s strengths.

Develop a growth trajectory and raise capital by seeking out seed investment, possibly from the founder’s capital, friends, family, or crowdfunding. To raise capital, the founder must articulate a growth trajectory and develop and execute a capital-raising strategy.

Create a culture, define job functions, and develop a hiring process. Once raised, the founder should use the capital to hire employees with skills in fields such as product development, sales, and marketing. Before hiring those employees, the founder must articulate the firm’s culture, define general job functions, and create a process for hiring and motivating talent.

Stage 2: Building a Scalable Business Model

Refine the company’s growth trajectory. The founder must next develop a more specific growth trajectory, making clear choices about its revenue and market share goals. The founder should decide which customer groups the startup will target; how it will make, sell, and service its product; and how it will identify and manage supply and marketing partnerships. Finally, the founder must estimate how much capital the startup will need to achieve its goals.

Raise more capital. The founder must gather additional capital from investors who have achieved success in industries similar to the startup’s and are eager to help prepare the company for rapid growth.

Articulate culture. Since the company will begin hiring many new employees, the CEO, who may still be the founder, must articulate and communicate the culture more formally.

Define specialist jobs. In addition, the CEO must define all jobs more specifically, recognizing that the company is transitioning from mostly generalists to more specialists.

Refine hiring processes. The CEO must assess and improve the hiring process to keep the company competitive in the battle for talent.

Set and monitor goals companywide. The CEO should create processes and systems that encourage people to agree to meet and measure goals, the achievement of which will help the company grow.

Introduce coordinating processes. Finally, the CEO must create processes that coordinate the work of specialized functions such as product development , marketing, selling, service, and order fulfillment in a way that boosts efficiency and increases customers’ perception of the value of the startup’s products as the company scales.

Stage 3: Sprinting to Liquidity

Build a global growth trajectory. To achieve rapid expansion, the CEO must next develop a growth trajectory that sets specific revenue goals and makes clear choices about sources of revenue from current and new customer groups, current and new geographies, built and acquired products, and current and new capabilities.

Raise more capital. The global growth trajectory should help the CEO develop an investor pitch deck which includes revenue and market share goals; choices about sources of revenue; how the company will make, sell, and service its product; how it will develop and manage supply and marketing partnerships; how much capital the startup will need to achieve its goals; and how it will provide a return for investors. The CEO should meet and pitch venture capital investors who embrace the CEO’s vision and can offer capital, contacts, and advice to help achieve the vision.

Articulate its culture. When the company goes global, it must pick a global language for communicating and then articulate the culture in that language while telling stories that global employees find compelling.

Define global jobs. The CEO must focus on hiring and motivating global general managers and help them to define the mix of specialist and generalist jobs that will be needed to achieve the startup’s goals in each country. As the company adds new products, the CEO must hire people to build those products and/or acquire companies that have done so already.

Refine global hiring processes, set and monitor goals globally, and introduce global coordinating processes. The CEO must adapt the company’s processes for hiring, setting, and monitoring the achievement of goals, and coordinating work to satisfy the cultural and other differences across each country in which the startup operates.

Stage 4: Running the Marathon

Build a high-speed growth trajectory. To continue to expand rapidly after its IPO, the CEO must set ambitious growth goals and chain together growth trajectories including current and new customer groups, current and new geographies, built and acquired products, and current or new capabilities. Often such growth trajectories depend on capabilities and culture that lead to high customer retention coupled with adding adjacent products that loyal customers want to buy and expanding into new customer groups.

Raise more capital. By going public, a company will have easier access to the capital it needs to build its growth trajectories; it will be able to sell more stock if needed or borrow money to finance acquisitions.

Formalize its culture. As Jeff Bezos has done with Amazon, CEOs must define clearly their company’s values and apply formal processes for key activities ranging from hiring, rewarding, and firing people to structuring meetings in order to motivate employees to act according to the company’s values. Because a public company has so many employees, the CEO must hold meetings virtually through electronic, video, and one-to-many dialogues.

Create and manage cross-functional teams. To keep a public company growing, the CEO must create dozens of cross-functional teams to take charge of specific business challenges, such as developing new products, sustaining high customer satisfaction, expanding into new countries, integrating acquisitions, and recruiting and motivating top talent. To keep growing, a public company needs functional experts who can lead the execution of key repeatable processes such as closing sales and creating financial reports.

Lead formal planning and reporting processes. The CEO must adapt the company’s processes for hiring, setting, and monitoring the achievement of goals and coordinating work to satisfy the cultural and other differences across each country in which the startup operates. To that end, CEOs must lead long-term strategic planning processes that encourage teams to buy into the company’s financial targets and strategic initiatives; to prepare annual budgets; to meet quarterly to compare actual progress with budget results; and to take corrective action where needed.

Case Study: ThoughtSpot Grows to Over 250 People

This scaling model seems to be applicable to real startups. An example is Palo Alto, California-based ThoughtSpot, a provider of operations information to help companies cut costs and boost revenues. ThoughtSpot CEO Ajeet Singh has the distinction of founding another company, Nutanix, a publicly traded information storage company, and his 4% stake was worth $280 million as of March 6, 2018, the day I interviewed him. As we’ll see in Chapter 3, such success is very helpful for a founder’s efforts to raise capital for a new startup.

In 2012, Singh started ThoughtSpot “to help him realize his vision to deliver analytics at human scale to 20 million users by 2020.” ThoughtSpot grew quickly. In the 12 months ending in November 2017, its customer count grew 227%, including 32 Fortune 500 companies and 12 Fortune 100 companies. Customers willing to share publicly that they worked with ThoughtSpot included Amway, De Beers, Chevron, Miami Children’s Hospital, Bed Bath & Beyond, and Capital One. ThoughtSpot’s headcount increased 67% to over 250 and it opened new offices in Seattle and Bangalore to add to its headquarters in Palo Alto and its EMEA headquarters in London. At the time, ThoughtSpot was continuing to grow. As Singh said in a March 2, 2018 interview, “We exceeded our plan for the year ending January 30 and we’re growing at an excellent rate. We are selling well with the largest 5,000 global companies, who make up 70% of the spend on analytics and business intelligence technology.”

Maintain a growth culture but change the way it is communicated. If a company achieves initial success, there is value in maintaining its culture as it scales. Singh believes that the founders’ values determine a company’s culture but as the company grows, new employees will not intuitively grasp those values unless the company communicates those values in a systematic way.

Change the mix of people as you scale. Early in a company’s development it needs builders—people who are willing to take on many different roles and are eager to do whatever necessary to get the company off the ground. At some point, such people are no longer useful because they resist formal processes, so the CEO must replace some of them with scalers or formal process experts. As Singh said, “In the $1 million to $10 million growth tier, a company needs builders. But as it goes from $10 million to $100 million, the company needs a mixture of builders and scalers. And as it goes from $100 million to $1 billion, it needs more maintainers who help keep customers happy.”

Replace generalists with specialists. Along with changing the mix of people, companies must hire more specialists as they grow, while encouraging them to team up to make decisions and take action. “Some generalists can specialize. But usually they have to be replaced by executives with specific functional expertise. For example, the executive in charge of Administration may need to be replaced by a VP of Finance, VP of Human Resources, and a CFO,” said Singh.

Make functions accountable for growth. When a company sets its sights on the next growth tier, different functions must figure out how their contribution to the goal should be measured. “It is easy for different functions to have metrics but not get to the right place. You need to ask how each function can contribute to the growth target. For example, customer service might set specific customer retention targets, sales will have revenue goals, and country managers will have their own metrics,” said Singh. “And functions should have leading indicators, such as the sales pipeline or leads generated by marketing. It’s important to be realistic about how each function can contribute to the goal. It is so easy to have a bad metric.”

Stay connected to global team members. To grow from, say, $10 million to $100 million and beyond, companies must expand into new countries. And to make those country leaders effective, the CEO must keep them feeling connected. As Singh said, “You have to empathize with them and realize that it’s a lonely job. You should give them the flexibility to optimize locally. And you should set a time for an all-hands meeting that works for the schedules of those around the world.”

Keep being CEO if you love the job. It is rare that a CEO can keep running a company as it scales beyond its initial public offering. Such marathoners, who can keep a company they founded growing after it goes public, are more valuable to a region and to investors than sprinters who take an idea and build it into a company that gets acquired. Marathoners like Jeff Bezos keep learning. As Singh said, “You have to maintain your intellectual curiosity and be willing to ask for feedback. The key questions I ask myself are: ‘Do I feel bogged down or not? Am I having fun? Do people respect me or are they following orders? Are we hitting our goals? Are good people staying and doing well?’ Every six months I ask for anonymous feedback on these questions.”

What Is Different About the Startup Scaling Model?

Due to the benefits of scaling, recent research suggests that the ability to do it well is of great interest to entrepreneurs. While many venture capitalists, consultants, and academics have written about scaling, a comprehensive framework for scaling remains to be created.

Consider the results of a May 2018 CNBC survey of its Disrupter 50 companies. The survey found that about 30% of respondents said that scaling the company was their biggest entrepreneurial challenge. The same percentage found that hiring qualified talent was the biggest challenge. Sadly, the survey did not define what these CEOs meant by scaling, nor did it examine why scaling was such a challenge or what scaling levers and practices they found most useful or most prone to failure.

- Tom Eisenmann, Harvard Business School’s Howard H. Stevenson Professor of Business Administration, defined scaling as what happens after a company reaches the product/market fit stage. He said that practitioners such as Eric Reis and Steve Blank have provided effective ways to think about how to reach that stage. As he said, “There is remarkably little good stuff written about scaling. I see the need for a framework.” Eisenmann argued that once a company achieves product/market fit, it is in a stronger position to seek out resources that it previously did not control so the CEO can acquire, organize, coordinate, and manage more resources. Noting that 60% of founders do not survive their startup’s Series D round of funding, Eisenmann highlighted various ways that founders fail to scale. They cannot

Win customers outside their core market profitably.

Tell customers, employees, and investors the truth when their ambitious goals prove out of reach.

When creating a new business, let go of formal processes designed for the core.

Resolve cultural battles between subgroups such as the old guard and new employees.

Be realistic about growth depending on “a cascade of miracles” such as many uncontrollable factors all going well.

- Gad Allon, the Jeffrey A. Keswin Professor and Professor of Operations, Information, and Decisions, and the Director of the Management and Technology Program at the University of Pennsylvania, offered key insights about the importance of designing a business model that enhances a startup’s competitive advantage as it scales. For example, Allon explained, “The most successful founders are good at product, organization, or in rare cases both. Zuckerberg, Evan Spiegel (Snap), and Reid Hoffman (LinkedIn) focus on product. Organization was not always top of mind or their greatest skill. So they brought in others to help with organization. Zuckerberg hired Sheryl Sandberg and Hoffman hired Jeff Weiner.” Bezos is the rare individual who can do both. “Bezos was always thinking both about how to develop products and how to build an organization. For example, with Amazon Fresh, Bezos wanted to start small, trying to optimize the logistics of grocery delivery work in Seattle before expanding to San Francisco where he realized that he needed to organize by zip code.” Allon argued that companies should scale only after the CEO has built a business model that will yield lower costs and greater customer value as the company gets bigger. He highlighted three key principles:

Supply-side economies of scale: “Before scaling, companies must figure out how to lower their cost of acquiring and servicing customers as they grow. For example, Amazon achieved economies of scale by building a massive infrastructure and pooling inventory in a small number of locations,” he said.

Demand-side economies of scale: Startups should also capture what he called demand-side economies of scale. “To scale efficiently, companies must tap into network effects that make their product more valuable to customers and more difficult for competitors trying to lure away their customers for every new one they add to their network.”

Hot cause, cool solution: Another scaling challenge is creating a compelling corporate culture and effective performance measurements. “Effective scaling also depends on having a hot cause (a purpose that talented people find compelling) and a cool solution (an effective set of performance metrics that drive people to realize the company’s goals),” he said.

- Bob Sutton, a Professor of Organizational Behavior who has a courtesy appointment at Stanford Business School and tenure at Stanford’s School of Engineering, provided useful insights into how culture and process can help leaders to manage a growing organization:

Use culture to get work done the right way. A company like Amazon with a strong culture can scale because smart people can decide without getting top management’s input. As Sutton said “Mindset is the agreement about what is good and bad behavior. When I meet with companies, I ask two questions: ‘What’s sacred?’ and ‘What’s taboo?’ When I asked those questions at Amazon everyone instantly agreed: the customer is sacred and wasting money is taboo (Amazon is really, really cheap).”

Do more with less. To manage growing teams, he thinks companies ought to be vigilant about subtracting processes that impede organizational effectiveness. As he said, “The best leaders treat it as a problem of more and less—they are always looking for things to subtract that don’t work any longer, that never worked, and that are getting in the way.” For example, in 2013 Dropbox sent out a companywide email entitled “Armeetingeddon has landed,” which eliminated all regularly scheduled meetings.

Slow down before speeding up. “When [traffic app] Waze raised a $35 million Series B round, its CEO Noam Bardin noticed that only 5% to 6% of the people who downloaded the app were still using it. He focused everyone on figuring out what was wrong with the software and what needed to be fixed. You can’t scale excellence if you don’t have excellence to scale,” said Sutton.

- Jeffrey Rayport, Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer, suggested that the most successful CEOs combine excellence in creating a compelling vision and in getting into the details of strategy execution. Rayport, who met Jeff Bezos in the 1990s, noticed that he was unique among the most successful founders in combining both attributes and that he was a voracious learner. Rayport also offered keen insights on several topics including the following:

Scaling culture: As he said, “Culture is not about being nostalgic about the good old days when there were no formal meetings and no HR department. It’s not one and done. As a company goes from 10 to 100 to 200 to 1,000 people, you might have the same values, such as integrity, transparency, teamwork, accountability, passion, and energy. But those are all outputs. For the culture to scale, you need to know what management levers you can pull to get people to act according to those values. For example, Bezos has physical, tangible rituals, such as leaving an empty chair at meetings for the customer and asking everyone to read a six-page memo prepared for a meeting before it begins.”

Strategy changes with scale: “It’s smart to look at the stages as relating to the different funding rounds, such as seed, Series A, B, and so on. The first stage is before you have product/market fit, at which point you are trying to raise seed capital from angel investors. Once you have product/market fit, which means customers are willing to pay for your product and you can scale up with profitable unit economics, you should capitalize to get big fast,” said Rayport.

- Shikhar Ghosh, HBS Professor of Management Practice, believes that as startups get bigger, their leaders must change how they manage the organization. He noted that these break points occur at powers of three, for example, 30, 90, 270, or 810 employees. Effective leaders must

Manage the tension between process and culture. According to Ghosh, “Managers come into the company and they want to create formal processes. But processes work for activities like accounting and not so well for creative work where it is better to set goals and let people figure out how to get there. Size often demands more formal processes, which is at odds with the history and mythology of the company, such as the idea that everyone worked 24 hours a day for a week before the end of a quarter in order to meet goals.”

Let go to go further. When a company gets bigger, the leader has to accept that new talent will do things differently—and make mistakes. But if the leader does not let go, the company will not be able to scale. As Ghosh said, “If the founder continues to be the chief problem solver, the people he hires to run, say, an operation in a new city will never become effective leaders. Instead, the founder should accept that as you create a new subgroup, there’s a V-curve. You will initially get less efficient. But after the subgroup makes mistakes and learns, it becomes more efficient and reaches a limit. If you intervene, you do worse.”

Make a common purpose stronger than chaos. As a company scales, the leader should make sure that the centripetal forces are stronger than the centrifugal ones. “As a company grows, it gets more specialized. Specific business functions want to optimize themselves, which pulls the company apart. The only way to keep functions like engineering, finance, sales, and so on together is to continuously remind everyone of the company’s purpose, mission, values, and desired behaviors,” he said.

Ranjay Gulati, Jaime and Josefina Chua Tiampo Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, argued that scaling can only happen if leaders add structure and processes and formalize culture, According to Gulati, “Firms must hire functional experts to take the enterprise to the next level, add management structures to accommodate increased head count while maintaining informal ties across the organization, build planning and forecasting capabilities, and spell out and reinforce the cultural values that will sustain the business. This approach to scaling will make a firm more efficient and help it find and exploit new opportunities.”

- Bill Aulet, Managing Director of the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, offered insights on three topics:

Specify the founders’ ambitions. Aulet said that the founders must decide whether their idea is “(1) a feature, (2) a product, or (3) a company.” What’s more, they should recognize that the risk, opportunity, resources required, and management challenges all rise with the founder’s ambition.

The importance of culture. He considers culture a “silent supervisor” and advocates that a CEO must explicitly define the company’s core values and “then make them visible through stories, the personnel appraisal process, public relations, incentives, real estate, hiring policies, and articulating clear reasons why the world is a better place because the organization exists.”

How jobs change with scale. As he said, “At first you need change agents and leaders to create new markets but then you must add managers who know how to optimize, control risk, and make more predictable results without losing the innovation brought by the change agents. The [change agents and managers] must coexist and be respectful of each other. But as you get bigger, you have more to lose and the managers become more and more important but can’t dominate.”

This book’s scaling model draws on many of the insights developed by these professors, recognizing the importance of redefining organizational roles, formalizing culture, creating processes for setting goals and measuring their achievement, and creating a business model that will create supply and demand economies as the company grows.

However, unlike these approaches, this book places scaling in the context of a startup’s stakeholders, including investors and partners. Although others place emphasis on important stakeholders such as employees and customers, investors and partners are not a key focus of their approaches. To that end, the book adds two important scaling activities which are not addressed extensively by other models: building growth trajectories and raising capital. This book’s scaling model also defines four stages of scaling and provides a structure that CEOs can use to reinvent the company as needed to keep it growing.