Chapter 9. Am I Becoming a Bad Rebel?

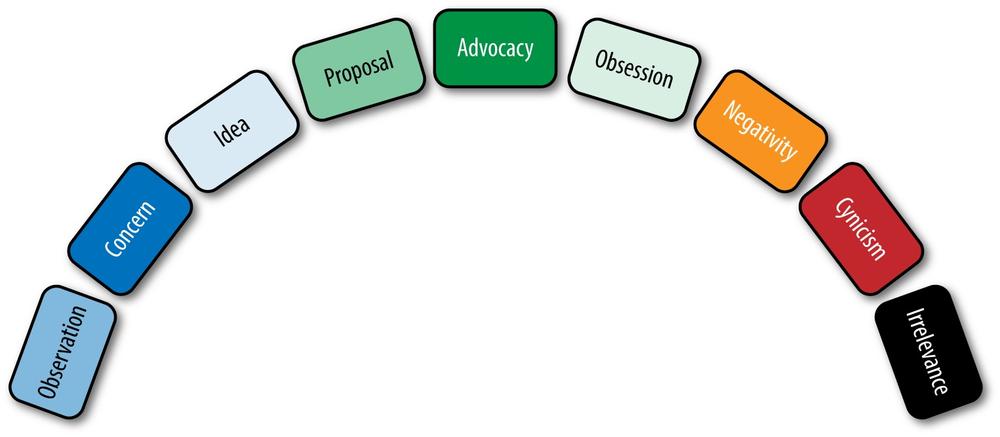

Each rebel journey is unique. But all unsuccessful journeys—especially when you don’t take the time to take care of yourself and maintain your rebel fitness—will look a lot like the rebel arc (Figure 9-1).

You notice something that needs fixing.

You come up with your idea.

You get a hearing, which is fair or less fair. Your ideas don’t receive the acclaim you expected. They’re just not a priority for the leadership team.

You get frustrated, and then, if you’re not careful, slide into obsession.

You don’t give up. You can’t take no for an answer.

You don’t notice how your tone is changing. In fact, many rebels never really understand why people start calling them cynical and negative.

But people at work notice you’ve changed. They can tell right away. You have slipped into obsession. Next stop—negativity. You’ve become so pessimistic and angry that people no longer consider your ideas, and you fall into irrelevance.

You are becoming a bad rebel.

Avoiding Bad Rebel Behavior

Most rebels we’ve talked to admit their behavior sometimes falls on the bad side of the rebel ledger. There are some circumstances in whic such “bad behavior” is unavoidable and even necessary (see “Bad Rebel Doing Good”). But in general, bad rebels cannot survive long in most organizations.

Table 1-1, which lists the characteristics of good versus bad rebels, is a useful diagnostic tool for rebels. And if you follow the suggestions we made in Chapter 8 about how to stay fit as a rebel and when to pull over to take a rest, the chances you will stumble into bad-rebel traps are reduced but unfortunately not eliminated. The emotional pressures associated with being a rebel at work are so great that we need all the concrete advice we can get to help us build more productive behaviors. So in the spirit of this handbook, we offer these five practices to follow no matter where you are in your rebel journey. Think of them as a mantra; repeat them often so you don’t forget.

1. Play Within the Rules

We can get so disgusted with office politics and bureaucratic nonsense that we start ignoring rules that seem ridiculous. Of course, there is no dearth of rules to ignore; bureaucracies create rules the way urban freeways create traffic jams and pretty much with the same effect.

Breaking rules, like being angry, might give you a momentary surge of “Take that, you idiots.” Or, “That really showed them, didn’t it?” But deciding unilaterally not to follow certain procedures is a reliable way to be identified as a troublemaker. With that label, you can’t gain the maneuvering room and credibility you need to make something important happen.

Creating change at work is a lot like playing chess: The more you understand the rules, the more you can use them to your advantage. Break the rules, and you lose the game. Rebels are in the organization and in the game. If you don’t want to work within the rules, get out and create your own organization and rules.

2. Keep Your Sense of Humor

Over the years, we have met way too many humorless rebels at work. Their passion for change has deteriorated into an earnest doggedness that repels people. They respond to any attempt by others to cheer them up by barking, “There’s nothing funny about watching this business go down the drain!”

These individuals usually come by their bad humor honestly; they suffered one too many organizational setbacks. Their careers are in disarray and they still can’t get anyone to support their ideas. It all seems like such a waste.

It is difficult to regain your sense of humor, so it’s helpful for aspiring rebels at work to understand from the get-go the importance of humor and laughter. We think they bring three distinct advantages:

- Your sense of humor is an important self-defense mechanism.

- This may sound a bit circular, but your ability to laugh at your setbacks and your own mistakes helps you keep a balanced perspective during your rebel journey. It’s hard to see the funny side of personal and professional disappointment, which is why it’s important for rebels to separate their egos from their ideas. Even if you can’t laugh at the time about the dressing down you got from your boss, relax with a friend soon after who can help you appreciate the absurdities. Laughter also has health benefits, and we rebels need to keep our blood pressure under control.

- Your sense of humor can win you more supporters.

- Writing in Harvard Business Review,[6] emotional intelligence expert Daniel Goleman and others argue that an executive’s sense of humor is an important business asset. An executive who is happy makes people “optimistic about achieving their goals…and predisposes them to be helpful.” You can use humor to lighten the mood of any meeting. You can also use humor to signal receptivity to comments and improvements to your ideas.

- Your sense of humor can help you welcome laughter in meetings.

- When we take ourselves too seriously, we are all too likely to frame laughter as a form of hostility rather than what it is: an indication that people are surprised by something unexpected. In essence, if someone laughs at your ideas, that person is helping you identify which of your change ideas is potentially most disruptive. We’re all familiar with the concept of nervous laughter. People tend to laugh when an idea is completely new. You should be more worried if no one laughs at your ideas.

3. Be an Idea Carrier, Not an Idea Warrior

Beware of thinking that your rebel concept is the one big idea, the silver bullet, or the once-in-a-career opportunity. Remember in Chapter 4 where we talked about the reason so many inhabitants of the organizational landscape resist change? It’s because many are trying to keep their one big idea or career-making program or policy alive. We rebels can believe that we own the change agenda in our organizations, and that our experiences and the way we like to do things should become the new orthodoxy. Avoid these behaviors at all costs.

Ideas have their own trajectory. We are the carriers of new ideas; rarely do we “own” them. Just making the mental shift from being an idea owner to an idea carrier can be a game changer. If you are carrying an idea, your number one goal should be to get other people to share the burden—and possibilities—with you. Infect others as soon as you can. Let your idea mutate as it makes contact with other ideas. Make the idea independent of you as soon as you can.

4. Don’t Play the Hero

Heroism is not a rebel strategy. Repeat after us. Heroism is not a strategy.

The problem with the ideal of the heroic rebel is that a lone individual is unlikely to triumph over the forces of organizational inertia. Sometimes organizations anoint individuals as saviors, and that usually doesn’t work either. The person anointed as the hero is also at considerable risk of believing what people say about him.

Some rebels are probably still storming the ramparts in hopes of overwhelming those who don’t get it. In our experience, most organizations become wiser slowly. People start having aha moments here and there. As a rebel, you often have the aha moment sooner than others. If the organization wants to anoint you as a hero for seeing the solution first, resist!

5. Find Your True Rebel Calling

Throughout this book, we’ve assumed that you have a specific set of ideas for improving the work of your organization. We’ve suggested tactics and strategies that we think, based on our careers and our research, will give you a better chance of success. All rebels start as advocates of specific changes. But over time, true rebels find a higher calling. The most important evolution your group needs is to become permanently open to new ideas. At that point, your ideas seem less important, and helping advance all good ideas becomes your true calling.

Organizations today are desperate to become more innovative. And we rebels are in a position to help them. If you get off today’s innovation bandwagon for a moment, you’ll realize that any one innovation in and of itself can’t provide the solution. Even if the innovation solves the current problem, it will soon fall behind a new emerging reality. Today’s shiny new innovation is doomed to become tomorrow’s conventional wisdom.

The issue is not so much whether you are innovative but whether you are thoughtful about what you’re doing. The issue isn’t whether our big idea will happen as much as whether we are helping to create a culture at work where new ideas are considered, discussed, and debated with respect, and given a possible trial. Rebels provide the most value when we help our organizations create thoughtful ways to examine new ideas and identify when it’s time to refresh processes and experiment with new approaches. Perhaps the greatest calling for rebels is for us to help organizations evolve from protectors of accepted orthodoxy to discoverers and promoters of new ideas.

Questions to Ponder

- Where are you on the rebel arc? What’s your next step to move to—or back to—the center of the arc, advocacy?

- What has happened to you when you’ve been obsessed about an idea or change proposal?

- How many rebel practices come naturally? Which do you have to work on?

- Do you laugh at yourself? Are you relaxed when you talk to others about your ideas?

- Are you bringing people in to be part of your change initiative? Or are you attempting to be a hero?

- What might your workplace be like if there were a culture where new ideas are thoughtfully considered? What could you and your rebel allies do to create a welcoming culture for new ideas?

[6] Daniel Goleman, Richard Boyatzis, and Annie McKee. “Primal Leadership: The Hidden Driver of Great Performance,” Harvard Business Review 79:11 (2001): 42–53.